Raise the Titanic (film)

Raise the Titanic is a 1980 adventure film produced by Lew Grade's ITC Entertainment and directed by Jerry Jameson. The film, which was written by Eric Hughes (adaptation) and Adam Kennedy (screenplay), was based on the 1976 book of the same name by Clive Cussler. The story concerns a plan to recover the RMS Titanic due to the fact that it was carrying cargo valuable to Cold War hegemony.

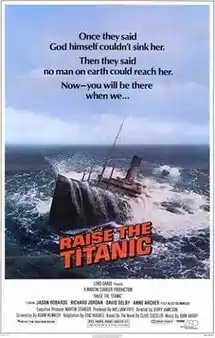

| Raise the Titanic | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jerry Jameson |

| Produced by | William Frye Lord Grade |

| Screenplay by | Adam Kennedy |

| Story by | Eric Hughes (Adaptation) |

| Based on | Raise the Titanic! by Clive Cussler |

| Starring | Jason Robards Richard Jordan David Selby Anne Archer Dirk Blocker Sir Alec Guinness |

| Music by | John Barry |

| Cinematography | Matthew F. Leonetti |

| Edited by | Robert F. Shugrue J. Terry Williams |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Associated Film Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $40 million[1] |

| Box office | $7 million[1] |

The film starred Jason Robards, Richard Jordan, David Selby, Anne Archer, and Sir Alec Guinness, it received mixed reviews by critics and audiences and proved to be a box-office bomb. The film grossed about $7 million against an estimated $40 million budget. Producer Lew Grade later remarked "it would have been cheaper to lower the Atlantic".[2][3]

Plot

The film opens on the fictional island of Svardlov in the Barents Sea north of the Soviet Union where an American spy breaks into an old mine and discovers the frozen body of a U.S. Army sergeant and mining expert Jake Hobart. Next to Hobart's corpse is a newspaper from November 1911, as well as some mining tools from the early part of the 20th century. Using a radiation meter, the spy discovers that what he seeks, an extremely rare mineral named byzanium, was there but had been mined out leaving only traces. He is then chased and shot by Soviet forces, but is rescued at the last moment by Dirk Pitt (Richard Jordan), a former U.S. Navy officer and a clandestine operator.

It is explained by scientist Gene Seagram (David Selby) and the head of the National Underwater and Marine Agency (NUMA, a NASA-like agency for sea exploration) Admiral James Sandecker (Jason Robards) that the mineral their man was trying to find is needed to fuel a powerful new defence system, codenamed "the Sicilian Project". This system, using laser technology, would be able to destroy any incoming nuclear missiles during an attack and "make nuclear war obsolete".

The CIA and Pitt soon find out that boxes of the raw mineral were loaded onto the Belfast-built RMS Titanic by an American in April 1912. A search is then conducted in the North Atlantic to locate the sunken ocean liner. The search team is aided by one of the Titanic's last survivors (Alec Guinness), who explains he was also the last person to see the American alive. Just before the Titanic went down, the junior officer said the man locked himself inside the ship's vault containing the boxes of mineral ore, his last words being "thank God for Southby!" At this point it is decided that the only way to recover the byzanium is to literally "raise the Titanic" from the ocean floor. Pitt comes up with a salvage plan that Sandecker presents to the U.S. president. The president signs off on the plan and Pitt is put in charge of the operation.

At this time the Soviet KGB station chief in Washington, D.C., Andre Prevlov (Bo Brundin), is receiving bits of information on the project and leaks them to a reporter, Dana Archibald (Anne Archer), who is also Seagram's lover as well as a former girlfriend of Pitt's. The story blows the project's secret cover and Sandecker must hold a press conference to explain why the ship is being raised. Questions are raised about byzanium, but are not answered.

After a lengthy search, the Titanic is located and the search team, with help from the U.S. Navy, begins the dangerous job of raising the ship from the seabed. One of the submersibles, Starfish, experiences a cabin flood and implodes. Another submersible, the Deep Quest, is attempting to clear debris from one of the upper decks when it suddenly tears free of its supports, crashes through the skylight above the main staircase and becomes jammed. Pitt decides they must attempt to raise the ship before the Deep Quest crew suffocates.

Eventually, the rusting Titanic is brought to the surface using compressed air tanks and buoyancy aids. During the ascent, the Deep Quest safely breaks away from the ship.

When Prevlov, who has been aboard a nearby Soviet spy ship, sees the Titanic, he arranges a fake distress call to draw the American naval escorts away from the operation. He then meets Sandecker, Pitt, and Seagram aboard their vessel. He tells them that his government knows all about the mineral and challenges them for both salvage of the Titanic as well as ownership of the ore, claiming it was illegally taken from Russian soil. Prevlov says that if there is to be a "superior weapon" made from the mineral, then "Russia must have it!" Sandecker tells Prevlov that they knew he was coming and that he would threaten them. Pitt then escorts him to the deck where U.S. fighter jets and a nuclear attack submarine have arrived to protect the Titanic from their attempted piracy. Prevlov leaves in defeat.

The ship is then towed into New York harbour and moored at the old White Star Line dock, its original intended destination. The arrival is greeted with much fanfare, including huge cheering crowds, escorting ships, and aircraft. On entering the watertight vault, the salvage team discovers the mummified remains of the American, but no mineral. Instead, they find only boxes of gravel. As they contemplate their probable failure, Sandecker tells Pitt and Seagram that, in addition to powering the defensive system, they were actually thinking of a way to weaponise the byzanium and create a superbomb, which went against everything the scientist believed in. As Pitt listens, he goes through the belongings of the dead American found in the vault and finds an unmailed postcard. He then realises that there was a clue in those final words, "thank God for Southby!". The postcard showed a church and graveyard in the fictional village of Southby on the English coast, the place the American had arranged a fake burial for the frozen miner Jake Hobart prior to sailing back to the United States on the Titanic. Pitt and Seagram alone go to the small graveyard and find that the byzanium had indeed been buried there. They decide to leave the mineral in the grave because they agree its existence would destabilise the status quo that maintains the peace between the West and the Soviet Union.

Cast

- Jason Robards as Admiral James Sandecker

- Richard Jordan as Dirk Pitt

- David Selby as Gene Seagram

- Anne Archer as Dana Archibald

- Sir Alec Guinness as John Bigalow

- Bo Brundin as Captain Andre Prevlov

- M. Emmet Walsh as Master Chief Vinnie Walker

- J.D. Cannon as Captain Joe Burke

- Norman Bartold as Admiral Kemper

- Elya Baskin as Marganin

- Dirk Blocker as Merker

- Robert Broyles as Willis

- Paul Carr as CIA Director Nicholson

- Michael C. Gwynne as Bohannon

- Harvey Lewis as Kiel

Development

The novel was published in 1976. In August of that year it was reported producer Robert Shaftel had the film rights.[4] The following month however it was clarified that the film rights had not yet been offered.[5]

Stanley Kramer

Lew Grade said he read the novel by Clive Cussler and became interested, thinking there was potential for a series along the lines of the James Bond films. He discovered that Stanley Kramer was interested in directing, and Grade said he would buy the rights to the book and let Kramer direct and produce.[6][7] (Kramer was making The Domino Principle for Grade.) In October 1976 Grade announced he had the film rights for a reported $450,000.[8]

The book came out in late 1976 and was a best seller.[9] In the summer of 1976 Kramer filmed footage from a Bicentennial Ball which he hoped to use in the movie.[10]

In January 1977 Kramer announced he had signed contracts to direct the film, which would be produced by Marvin Starger.[9] In March Grade announced he had optioned the rights for two other Dirk Pitt novels, Iceberg and The Sea Dweller.[11]

At the Cannes Film Festival in May 1977, Lew Grade announced the film as part of a slate of projects which included The Boys from Brazil, The Golden Gate (from a novel by Alistair MacLean directed by Jerry Jameson), and $1.97 about the early years of Charles Bronson.[12]

Pre-production began and models of the ship were built; Grade said that the models were at least two or three times larger than they should be.[13] The model was based on blue prints of the actual Titanic and were built at CBS Cinema Centre in Studio City at a cost of $5–6 million.[10][14]

Eventually in December 1977 Lew Grade announced that Kramer had left the project due to creative differences. Kramer said "the factors were casting and the number of miniatures we planned to use. You might say one of the possibilities as to why I left was that I felt things might have cost more. It's aways a little sad to see it happen this way. Raise the Titanic was a big challenge – all the excitement of special effects, underwater filming."[15] Kramer said the producers wanted the movie made for $9 million but he felt it would cost $14 million.[16] Kramer was paid off with a fee of $500,000.[17]

Jerry Jameson

In May 1978 Lew Grade announced the film would be directed by Jerry Jameson, who had been attached to The Golden Gate, which had not been made. Grade said the movie would be his most expensive yet, costing $20 million, but would not feature any major stars. "We don't need them", he said. "The ship is the star. Anyway the money that would normally go to actors has been spent on our models. They're magnificent." Grade said the models cost $5 million.[18] William Frye, who produced Jameson's Airport 77, was hired to produce.[10]

Production costs spiralled to US$15 million as work was undertaken to find a ship that could be converted to look like the sunken Titanic.[19]

It was felt that the real Titanic, if raised from the bottom of the ocean, would come up rather gradually at a gentle angle, before levelling off on the surface. The tank in North Hollywood was too shallow and would launch the model like a rocket ship. It was decided to film in a bigger tank.[14]

In December 1978 construction began on a water tank in Malta to film the underwater scenes. "Malta was the only place we could find an existing tank with the right location and the right surroundings", said Grade.[20]

A double for the Titanic was found in Athens.[10]

Screenplay

The screenplay also underwent numerous rewrites.[21] The first writer to work on it was Adam Kennedy, who wrote the script for Stanley Kramer's film for Lew Grade, The Domino Principle. He was followed by Eric Hughes, Millard Kaufman and Arnold Schulman. Kennedy was brought back to do further revisions on the script and he gets sole credit.[10]

Novelist Larry McMurtry – who disliked Cussler's novel, considering it "less a novel than a manual on how to raise a very large boat from deep beneath the sea" – claims that he was one of approximately 17 writers who worked on the screenplay and the only one not to petition for a credit on the finished film.[22]

Admiral David Cooney, Chief of Information for the Navy, demanded the script be rewritten so as the Russians did not come off smarter than the Americans.[14]

Cussler was furious with the final result, because most of the original plot had been rejected leaving a hollow shell of his story; additionally he felt that the casting was wrong.

Casting

Elliott Gould was offered a lead role, but turned it down. "I don't want to raise the Titanic", he said. "Let the Titanic stay where it is", he said.[23]

Jason Robards said he did the film for "money, m'dear, money... We're all incidental to the hardware and the special effects on this one." [24]

In October 1979 it was announced Richard Jordan would play Dirk Pitt.[25]

Clive Cussler made a cameo in the film as a reporter at the script conference.[26]

Filming

Filming started in October 1979 at CBS Studio Centre. By this stage $15 million had already been spent on the tank and models.[10]

An old Greek ocean liner, SS Athinai, was converted into a replica of the Titanic. A scale model was used for close-up underwater scenes. At the time of filming there were conflicting views as to whether the Titanic had broken up as she foundered based on the original eyewitness testimony of the survivors, and – in line with the novel's assumption against the break-up narrative – the ship was portrayed as intact in the film. In 1985 the wreck of the real Titanic was located, confirming that she had broken up during the disaster, and lay in two pieces on the bottom of the North Atlantic in a state of advanced corrosion.

A 10-tonne 50 ft (15 m) scale model was also built for the scene where the Titanic is raised to the surface. Costing $7 million, the model initially proved too large for any existing water tank.[21] This problem led to one of the world's first horizon tanks being constructed at the Mediterranean Film Studios near Kalkara, Malta. The 10 million-gallon tank could create the illusion a ship was at sea. The Titanic model was raised more than 50 times until a satisfactory shot was acquired.

Following the completion of filming, the scale model was left to rust for 30 years at the side of the horizon tank (at 35°53′36.36″N 14°32′4.41″E). In January 2003 a storm caused damage to the model. By 2012 the remains of the metal structure had been moved to a new location closer to the sea (at 35°53′37.51″N 14°32′6.13″E).

The final scene involved Alec Guinness at St. Ives in Cornwall[27] over two days. The day before the shoot St Ives had its worst storm in one hundred years, destroying the church where the scene was to be shot so it had to be relocated.[14]

Soundtrack

John Barry created the film's musical score, which became the most acclaimed aspect of the production and is considered by many to be one of the very best of Barry's career – closely following the style of his soundtrack for the James Bond film Moonraker the preceding year, with militaristic passages reflecting the Cold War aspects of the plot to the dark, cold, brooding compositions reflected in the underwater scenes.

Though the original recordings of the music have been lost, Silva Screen Records, along with Nic Raine, one of Barry's orchestrators, commissioned a re-recording in 1999 of the complete score with the City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra.

In August 2014 Network On Air were to release Raise The Titanic on Blu-ray in the UK, with the only known available original Barry score. There are tapes from M&E which contain the score plus sound effects. There is no known source for the original, complete score.[28]

In March 1980 Marble Arch auctioned off props for the film among others.[29]

Release

In October 1978 it was announced the film would be released by a new distribution company, AFD.[30]

The film premiered in 1980. Twelve minutes were cut after the premiere.[31]

Reception

Raise the Titanic received mixed reviews and has a 43% on Rotten Tomatoes.[32]

Cussler was so disgusted with the film that he refused to give any permission for further film adaptations of his books[33] (in 2006, Cussler sued the filmmakers of Sahara, a film adaption of his 1992 book, for failing to consult him on the script when it also made huge financial losses).[34]

The film grossed $7 million against a budget of $40 million.[1]

Lew Grade later wrote that he "thought the movie was quite good", particularly the actual raising of the Titanic and the scene where Dirk Pitt walks into the wrecked ballroom. He blamed the failure of the film in part on the release of a TV movie on the topic, S.O.S. Titanic (released theatrically through EMI Films, of which Grade's brother, Lord Delfont, was then chairman).[6]

Raise the Titanic, along with other contemporary flops, has been credited with prompting Grade's withdrawal from continued involvement with the film industry.[35]

Nominations

- Nominated: Worst Picture

- Nominated: Worst Supporting Actor (David Selby)

- Nominated: Worst Screenplay

References

- "Raise the Titanic – Box Office Data". The Numbers. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- Fowler, Rebecca (31 August 1996), "It would be cheaper to lower the Atlantic", The Independent, London, retrieved 11 May 2009

- Kennedy, Duncan (25 August 2012). "Australian billionaire on mission to recreate Titanic". BBC News. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Lochte, Dick (29 August 1976). "book notes: Titanic epic that earns the title". Los Angeles Times. p. j2.

- Lochte, Dick (12 September 1976). "'Pop' goes Warhol's cash register". Los Angeles Times. p. u2.

- Lew Grade, Still Dancing: My Story, William Collins & Sons 1987 p 260-261

- BENEDICT NIGHTINGALE (10 February 1980). "Lord Grade: A Movie Mogul In the Classic Mold: Lew Grade at 73: A Classic Mogul". New York Times. p. D1.

- Kilday, Gregg (16 October 1976). "A Stand on 'A Matter of Time'". Los Angeles Times. p. b7.

- "Best Seller List". New York Times. 2 January 1977. p. 159.

- SCHREGER, CHARLES (20 October 1979). "Preproduction: A Titanic Task". Los Angeles Times. p. c6.

- Lochte, Dick (20 March 1977). "Sunny Skies Following 'Rain'". Los Angeles Times. p. u2.

- Champlin, Charles (27 May 1977). "CRITIC AT LARGE: In Search of World Viewers Incomplete Source". Los Angeles Times.

- Walker, Alexander (1985). National Heroes: British Cinema in the Seventies and Eighties. Harrap. pp. 198, 202. ISBN 9780245542688.

- Sally Ogle Davis (16 February 1980). "Raising the Titanic, Hollywood style $35 million later, Lord Grade gets that nasty sinking feeling". The Globe and Mail. p. E.5.

- Lee, Grant (31 December 1977). "FILM CLIPS: Gilbert Moses Lands a 'Fish'". Los Angeles Times. p. c6.

- Champlin, Charles (24 February 1978). "CRITIC AT LARGE: High Noon for Stanley Kramer CRITIC AT LARGE". Los Angeles Times. p. e1.

- Mann, Roderick (21 March 1978). "All That Glitter Isn't Sold--Yet". Los Angeles Times. p. e11.

- "The Gospel According to Heston". Los Angeles Times. 25 May 1978. p. f17.

- Suid, Lawrence H.Suid (2002). Guts and Glory. University Press of Kentucky. p. 413. ISBN 9780813190181.

- Barker, Dennis (20 December 1978). "Malta filming vital, says Grade". The Guardian. p. 6.

- Cettl, Robert (2010). Film Tales. Wider Screenings TM. p. 74. ISBN 9780987050007.

- McMurtry, Larry (2010). Hollywood: A Third Memoir. Simon & Schuster. pp. 59–60.

- Mann, R. (22 October 1978). "MOVIES". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 158662943.

- Sally Ogle Davis (22 August 1980). "Jason Robards enjoys both types of success". The Globe and Mail. p. 13.

- Smith, Liz (7 October 1979). "Philippines' First Family is taking Time to task". Chicago Tribune. p. l2.

- "VAN DEVERE'S PASSAGE TO INDIA: TRISH'S PASSAGE TO INDIA". Los Angeles Times. 31 January 1980. p. f1.

- "British Film Locations – Raise the Titanic". British Film Locations.

- "Raise the Titanic". Network on air. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Stein, Mark (27 March 1980). "PROPS, FILM EQUIPMENT SOLD AT STUDIO AUCTION: Film Items Sold at Studio Auction". Los Angeles Times. p. v1.

- Kilday, Gregg (28 October 1978). "FILM CLIPS: A New Dimension for a Brother Act". Los Angeles Times. p. b11.

- Champlin, Charles (1 August 1980). "CRITIC AT LARGE: LAUNCHING A NEW GENRE--SEA-FI". Los Angeles Times. p. g1.

- "Raise the Titanic".

- Cunningham, Lawrence A. (2012). Contracts in the Real World: Stories of Popular Contracts and Why They Matter. Cambridge University Press. p. 153. ISBN 9781107020078.

- Bunting, Glenn F. (8 December 2006). "Don't give him rewrite". LA Times.com. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018.

- Barber, Sian (2013). The British Film Industry in the 1970s: Capital, Culture and Creativity. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137163325.