White Star Line

The Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, more commonly known as the White Star Line (WSL), was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up as one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between the British Empire and the United States. While many other shipping lines focused primarily on speed, White Star branded their services by focusing more on providing steady and comfortable passages, for both upper class travellers and immigrants.

| |

| Type | Partnership |

|---|---|

| Industry | Shipping, transportation |

| Fate | Forced merger with Cunard Line by the British Government |

| Successor | Cunard White Star Line |

| Founded | 1845 in Liverpool, England |

| Defunct | 1934 |

Area served | Transatlantic |

| Parent | Ismay, Imrie and Co. |

| Website | www |

Today, it is remembered for the innovative vessel Oceanic of 1870, and for the losses of some of their best passenger liners, including the wrecking of RMS Atlantic at Halifax in 1873, the sinking of RMS Republic off Nantucket in 1909, the loss of RMS Titanic in 1912 and HMHS Britannic in 1916 while serving as a hospital ship. Despite its casualties, the company retained a prominent hold on shipping markets around the globe before falling into decline during the Great Depression, which ultimately led to a merger with its chief rival, Cunard Line, which operated as Cunard-White Star Line until 1950, when Cunard purchased White Star's remaining share. Cunard Line then operated as a separate entity until 2005 and is now part of Carnival Corporation & plc. As a lasting reminder of the White Star Line, modern Cunard ships use the term White Star Service to describe the level of customer care expected of the company.[1]

History

Early history

The first company bearing the name White Star Line was founded in Liverpool, England, by John Pilkington and Henry Wilson in 1845. It focused on the UK–Australia trade, which increased following the discovery of gold in Australia. The fleet initially consisted of the chartered sailing ships RMS Tayleur, Blue Jacket, White Star, Red Jacket, Ellen, Ben Nevis, Emma, Mermaid and Iowa. Tayleur, the largest ship of its day, was wrecked on its maiden voyage to Australia at Lambay Island, near Ireland, a disaster that haunted the company for years.[2]

In addition, the company also ran voyages from Liverpool to Victoria, British Columbia, which it promoted in Welsh newspapers[3] as being the gateway to the Klondike Gold Rush.[4] One of the ships on this route was the Silistria. Travelling around Cape Horn and stopping in Valparaiso and San Francisco, she reached Victoria after a trip of four months.

In 1863, the company acquired its first steamship, Royal Standard.[5]

The original White Star Line merged with two other small lines in 1864, the Black Ball Line and the Eagle Line, to form a conglomerate, the Liverpool, Melbourne and Oriental Steam Navigation Company Limited.[6] This did not prosper and White Star broke away. White Star concentrated on Liverpool to New York City services. Heavy investment in new ships was financed by borrowing, but the company's bank, the Royal Bank of Liverpool, failed in October 1867. White Star was left with an incredible debt of £527,000 (equivalent to £51,021,373 in 2019),[7] and was forced into bankruptcy.[6]

The Oceanic Steam Navigation Company

On 18 January 1868, Thomas Ismay, a director of the National Line, purchased the house flag, trade name and goodwill of the bankrupt company for £1,000 (equivalent to £90,638 in 2019),[7] with the intention of operating large ships on the North Atlantic service between Liverpool and New York. Ismay established the company's headquarters at Albion House, Liverpool.

%252C_Lobby%252C_Liverpool.jpg.webp)

Ismay was approached by Gustav Christian Schwabe, a prominent Liverpool merchant, and his nephew, the shipbuilder Gustav Wilhelm Wolff, during a game of billiards. Schwabe offered to finance the new line if Ismay had his ships built by Wolff's company, Harland and Wolff.[8] Ismay agreed, and a partnership with Harland and Wolff was established. The shipbuilders received their first orders on 30 July 1869. The agreement was that Harland and Wolff would build the ships at cost plus a fixed percentage and would not build any vessels for the White Star's rivals. In 1870, William Imrie joined the managing company. As the first ship was being commissioned, Ismay formed the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company to operate the steamers under construction.

The North Atlantic Run

The Oceanic class

White Star began its North Atlantic run between Liverpool and New York with six nearly identical ships, also known as the 'Oceanic' class: Oceanic (I), Atlantic, Baltic, and Republic, followed by the slightly larger Celtic and Adriatic. It had long been customary for many shipping lines to have a common theme for the names of their ships. White Star gave their ships names ending in -ic. The line also adopted a buff-coloured funnel with a black top as a distinguishing feature for their ships, as well as a distinctive house flag, a red broad pennant with two tails, bearing a white five-pointed star. In the initial designs for this first fleet of liners, each ship was to measure 420 feet in length, 40 feet in width and approximately 3,707 in gross tonnage, equipped with compound expansion engines powering a single screw, and capable of speeds of up to 14 knots. They were also identical in passenger accommodations based on a two-class system, providing accommodations for 166 First Class passengers amidships, which in those days was commonly referred to as 'Saloon Class' and 1,000 Steerage passengers.

It was within the circles of the massive tides of immigrants flowing from Europe to North America that the White Star Line aimed to be revered by, as throughout the company's full history they regularly strived to provide passage for steerage passengers which greatly exceeded that seen with other shipping lines. With the 'Oceanic' class, one of the most notable developments in steerage accommodations was the division of steerage at opposite ends of the vessels, with single men being berthed forward, and single women and families berthed aft, with later developments allowing married couples berths aft as well.

.jpg.webp)

White Star's entry into the Trans-Atlantic passenger market in the spring of 1871 got off to a rocky start. When Oceanic sailed on her maiden voyage on 2 March, she departed Liverpool with only 64 passengers aboard, from whence she was expected to make port at Queenstown the following day to pick up more passengers before proceeding to New York. However, before she had cleared the Welsh coast her bearings overheated off Holyhead and she was forced to return for repairs. She resumed her crossing on 17 March and ended up not completing the crossing to New York until 28 March. However, upon her arrival in New York, she drew considerable attention, as by the time she departed on her return crossing to Liverpool on 15 April, some 50,000 spectators had looked her over.[9] White Star's troubles with their first ship were short lived, as on Oceanic's second crossing to New York, on which she departed Liverpool on 11 May and arrived in New York on 23 May, she completed the crossing timely and with 407 passengers aboard.

In the eighteen months to follow, the five remaining ships were completed, and one by one, joined her on the North Atlantic run. Atlantic sailed on her maiden voyage from Liverpool on 8 June without incident. However, later that summer another problem surfaced which posed a threat to public opinion of the line. Of the six ships, the names originally selected for third and sixth ships of the fleet had initially been selected as Pacific and Arctic, which when mentioned in the press appeared alongside references two ships of the same names which had belonged to the since defunct Collins Line, both of which were lost at sea with large losses of life. In the cases of those ships, both of which had been wooden hulled paddle steamers, the Arctic had foundered of the coast of Newfoundland in September 1854 after colliding with another ship, resulting in the loss of over 300 lives, while the Pacific vanished with 186 on board in January 1856. As a result, White Star made arrangements to change the names of these two ships. The third ship of the fleet, which had been launched as Pacific on 8 March 1871 was renamed Baltic prior to its completion, a name which she sailed under on her maiden voyage on 14 September. At that same time, the keel of the last ship in the fleet, which had been named Arctic had just been laid at Harland & Wolff, and was thus renamed Celtic prior to her launch.

The fourth vessel of the Oceanic class, Republic sailed on her maiden voyage on 1 February 1872, around which time modifications were being made to the last two ships still under construction. Alterations in their designs called for their hulls to be extended in length by 17 feet, which for the Adriatic increased her gross tonnage to 3,888, and for Celtic her tonnage was increased to 3,867. Adriatic entered service on 11 April 1872, followed by Celtic six months later on 24 October. These ships began their careers with notable success, the most notable being Adriatic, which after barely a month in service became the first White Star ship to capture the Blue Riband, having completed a record westbound crossing in 7 days, 23 hours and 17 minutes at an average speed of 14.53 knots. In January 1873, Baltic became the first of the line to capture the Blue Riband for an eastbound crossing, having completed a return trip to Liverpool in 7 days, 20 hours and 9 minutes at an average speed of 15.09 knots.[10]

The first substantial loss for the company came only four years after its founding, occurring 31 March 1873 with the sinking of the RMS Atlantic and the loss of 535 lives near Halifax, Nova Scotia. While en route to New York from Liverpool amidst a vicious storm, the Atlantic attempted to make port at Halifax when a concern arose that the ship would run out of coal before reaching New York. However, when attempting to enter Halifax, she ran aground on the rocks and sank in shallow waters. Despite being so close to shore, a majority of the victims of the disaster drowned. The crew were blamed for serious navigational errors by the Canadian Inquiry, although a British Board of Trade investigation cleared the company of all extreme wrongdoing.[11]

Britannic and Germanic

In the wake of the Atlantic disaster, White Star ordered two new steamers from Harland & Wolff, both of which were designed as considerably larger, two-funneled versions of the Oceanic class steamers. These two ships measured in design at 455 feet in length, 45 in width, each with a gross tonnage of roughly 5,000 tons and with engines of similar design as seen in the earlier ships, with the exception of greater horsepower, capable of driving their single screws at speeds of up to 15 knots. Also increased was passenger capacity, as designs for these ships provided for 200 Saloon passengers and 1,500 Steerage passengers. The first of the pair, which had initially been named Hellenic, was launched as Britannic on 3 February 1874 and commenced on her maiden voyage to New York on 25 June. Her sister, Germanic was launched on 15 July of that same year, but due to a rather unsightly complication in her construction involving an experimental 'adjustable' propeller shaft which had to be removed, Germanic did not enter service until 20 May 1875. One notable development with the addition of these two ships was that with this addition, Oceanic was declared surplus and in the spring of 1875 was chartered to one of White Star's subsidiaries, the Occidental & Oriental Shipping company, under which she operated on their Trans-Pacific route between San Francisco, Yokohama and Hong Kong until her retirement in 1895.[12] The two new steamers proved immensely popular on the North Atlantic run, and both would end up capturing the Blue Riband on two eastbound and three westbound crossings within a two-year period. The Germanic captured the westbound record first in August 1875, then captured the eastbound record in February 1876, while Britannic captured both records within less than two months of each other, beating the westbound record in November and the eastbound record in December. Germanic captured the westbound record for the last time in April 1877.[13]

Teutonic and Majestic

Over the next 12 years, White Star focused their attention on other matters of business, expanding their services with the introduction of several cargo and livestock carriers on the North Atlantic as well as establishing a small but lucrative passenger and cargo service to New Zealand. By 1887, however, the Britannic and Germanic and the four remaining Oceanic class liners had aged significantly and were now being outdone in speed and comfort by newer ships brought into service by White Star's competitors such as Cunard and Inman. In an effort to outdo their competitors, White Star began making plans to put two new liners into service which would prove to be exceptionally innovative in design for the time, Teutonic and Majestic. In order to build these new ships, Thomas Ismay made arrangements with the British Government under which in exchange for financial support from the British government, the two new ships would be designed as not only passenger liners, but also as armed merchant cruisers which could be requisitioned by the British Navy in times of war. Measuring at 565 feet in length and 57 feet in width and with a gross tonnage of just under 10,000 tons, the new liners would be nearly twice the size of Britannic and Germanic. Additionally, owing to the arrangement with the British Government, the Teutonic and Majestic were the first White Star liners to be built with twin screws, powered by triple expansion engines capable of driving the ships at speeds of up to 19 knots.

In all, Teutonic and Majestic were designed to be built with accommodations for 1,490 passengers in three classes across four decks, titled 'Promenade', 'Upper', 'Saloon' and 'Main'; with 300 in First Class, 190 in Second Class and 1,000 in Third Class. Accommodations for passengers were based on the level of comfort on these sections of a ship. Those closer to the center axis of motion on a vessel felt little to no discomfort in rough seas. However those located near the bow and stern would experience every swell, wave and motion in addition to the noise of the engines in steerage. First Class accommodations, were located amidships on all four decks, with Second Class located abaft of first on the three uppermost decks on Teutonic and all four decks on Majestic, and Third Class located at the far forward and aft ends of the vessel on the Saloon and Main decks.

One notable development associated with the introduction of these two new ships was that they were the first White Star liners to incorporate the three-class passenger system. Prior to this, White Star had made smaller attempts to enter the market for Second Class passengers on the North Atlantic by adding limited spaces for Second Class passengers on their older liners. According to De Kerbrech, spaces for Second Class were added to Adriatic in 1884, Celtic in 1887 and Republic in 1888, often occupying one or two compartments formerly occupied by Steerage berths.[14]

In March 1887, the first keel plates of the Teutonic were laid at Harland & Wolff, while construction on Majestic commenced the following September. Construction on the two liners progressed in roughly six-month intervals, with the Teutonic being launched in January 1889 and sailing on her maiden voyage to New York the following August; while Majestic was launched in June 1889 and entered service in April 1890.[15] Prior to her entry into service, Teutonic made a rather noteworthy appearance at the 1889 Naval Review at Spithead. Although due to scheduling commitments she could not take part in the actual review, she anchored briefly amidst a line of merchant ships awaiting review, complete with four guns mounted, during which time she was toured by the Prince of Wales and Kaiser Wilhelm II. The Kaiser, much impressed with what he saw in Teutonic, is rumored to have mentioned to others in his party "We must have one of these!".[16] They would be White Star's last speed record breakers, as both ships would capture the Blue Riband in the summer of 1891 within two weeks of each other. Majestic beat the westbound record first on 5 August 1891, arriving in New York in 5 days, 18 hours and 8 minutes after keeping an average speed of 20.1 knots. This record was beat by Teutonic, which arrived in New York on 19 August and beat the previous record by 1 hour and 37 minutes, this time maintaining an average speed of 20.35 knots.[13]

With the introduction of Teutonic and Majestic, White Star did away with some of their aging fleet to make room for the new ships. Prior to the completion of the two new ships, Baltic and Republic were both sold to the Holland America Line and respectively renamed Veendam and Maasdam, after which they were put into service on the company's main Trans-Atlantic route between Rotterdam and New York. Veendam was lost at sea without loss of life after striking a submerged object in 1898, while Maasdam was again sold in 1902 to La Veloce Navigazione Italiana and renamed Citta di Napoli, after which she was used as an emigrant ship for an additional eight years before being sold for scrap at Genoa in 1910.[17] In 1893, by which time Teutonic and Majestic had established themselves on the North Atlantic run, White Star sold Celtic to the Danish Thingvalla Line, who renamed her Amerika and attempted to use her for their own emigrant service from Copenhagen to New York. This, however, failed to prove profitable for the line and she was sold for scrap at Brest in 1898.[18]

Cymric and the move from speed to comfort

Beginning in the late 1890s, White Star experienced an explosion of rapid growth and expansion of its services, highlighted by a dramatic shift in focus from building the fastest ships on the North Atlantic to building the most comfortable and luxurious. Their first step in this direction came in 1897 during the construction of a new ship, Cymric. Initially designed as an enlarged version of the livestock carrier Georgic, which had entered service in 1895, Cymric had been planned as a combination passenger and livestock carrier, and thus was not designed with engines necessary to qualify her for the express service maintained by Britannic, Germanic, Teutonic and Majestic. However, while she was under construction at Harland & Wolff, a decision was made to convert spaces aboard her designated for cattle into Third Class accommodations after it was deemed that carrying passengers and livestock aboard the same vessel would not likely prove a popular venture. Therefore, in addition to the accommodations planned for 258 First Class passengers, her designs were altered to include berthing for 1,160 Third Class passengers.[19]

Overall, her modest layout and design placed her with a footing directly between that of the aged but well reputable Britannic and Germanic and that of the more modern Teutonic and Majestic. Measuring at just over 13,000 tons and with a length of 585 feet and a beam of 64 feet, she was to be the largest liner in the White Star fleet, for a time at least. Additionally, her more utilitarian appearance with a single funnel and four masts contrasted her against her four running mates considerably. Because of this design, she was considered the first of White Star's 'intermediate' liners. However, as a result of this partial transition from livestock carrier to passenger liner, Cymric came to attain several noteworthy advantages which White Star would employ on several other liners. While her passenger accommodations had been modified, the specifications of her machinery and engines were left in place. Like Teutonic and Majestic, Cymric was fitted with twin screws, but was instead powered by quadruple expansion engines capable of achieving a modest speed of 15 knots commonly seen in cargo and livestock carriers of that time. The major difference was that because these engines were designed for more modest speeds, they were considerably smaller and required only seven boilers, leaving more space within the hull for passenger and crew accommodations.[20] At the same time, this also meant she consumed much less coal than steamers designed with larger engines, making her more economical. Cymric was launched at Harland & Wolff in October 1897 and entered White Star's North Atlantic service in February 1898, and in time proved a popular and profitable addition to the fleet.[19]

Oceanic and the death of Thomas Ismay

In the early months of 1897, while Cymric was still under construction at Harland & Wolff, it became clear to Thomas Ismay and other line officials that a new addition to the North Atlantic fleet was needed, as compared to the fleets of many of their competitors such as Cunard and North German Lloyd, White Star was lagging behind. By this point, the only remaining ship of the original 'Oceanic' class of liners was the Adriatic, and in her old age of a full quarter century, her days on the North Atlantic were now numbered. Britannic and Germanic were not too far behind after more than twenty years service, and with the advancements seen in shipbuilding during the 1890s Teutonic and Majestic had been eclipsed by several newer vessels, most recently North German Lloyd's Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. In response to this lagging, Ismay and his partners at Harland & Wolff set out to design two new liners for the North Atlantic run which would, in a fashion similar to how Teutonic and Majestic had done, go down in shipbuilding history.[21]

The new steamers, which were intended to be named Oceanic and Olympic, were designed to be both the largest and most luxurious the world had ever seen. In March 1897, the first keel plates for Oceanic were laid at Harland & Wolff, but almost immediately problems arose. Because the shipbuilder had never constructed a vessel of this size, work on the ship was delayed until an overhead gantry crane could be built. Her launch on 14 January 1899 drew an immense crowd of spectators numbering more than 50,000, as the launch placed Oceanic in history as the last British Trans-Atlantic liner to be launched in the 19th century as well as the first to exceed the Great Eastern in length. In all, she measured in at 704 feet (215 m) in length with a beam of 68 feet (21 m), and had a gross tonnage of 17,254, making her a full 42% larger than North German Lloyd's Kaiser Wilhelm Der Grosse. Like Teutonic and Majestic, Oceanic was designed with capabilities to be converted to an armed merchant cruiser in time of war if needed, specifications for which included her to be built with a double-plated hull and turrets on her upper decks which could be quickly mounted with guns.[22] She was also built with triple expansion engines geared to twin screws capable of achieving a respectable, if not record breaking, service speed of 19 knots. Additionally, she had a considerably larger passenger capacity of just over 1,700, providing for 410 First Class, 300 Second Class and 1,000 Third Class.[23]

Oceanic sailed on her maiden voyage from Liverpool on 6 September 1899, arriving in New York to much added fanfare on the morning of 13 September with 1,456 passengers aboard, many of whom were well satisfied with how the crossing had gone. Among those travelling aboard in First Class were Harland & Wolff's managing director, Lord Pirrie, and Thomas Andrews, who had designed Oceanic under Thomas Ismay's direction. At the time Oceanic made her departure from Liverpool a fireman's strike had been ensuing at the docks, which in turn meant she sailed with a boiler room crew consisting of fewer men than her specifications called for. Thus, during her maiden voyage her engines had been run and maintained an average speed of just under 19 knots. In an interview, Lord Pirrie had been asked why she hadn't broken any speed records. His reply was thus as follows: "The only record she is built to beat is that for regular running. She is to swing back and forth across the Atlantic with the regularity of a pendulum."[24]

Thomas Ismay was unable to enjoy the fruits of his labour. Just a few weeks after Oceanic was launched, Thomas began complaining of pains in his chest, from whence his health steadily began to decline. In fact, his health began to deteriorate so rapidly that managers with White Star and Harland & Wolff both decided to cancel plans to construct the second ship which was to serve as running mate to Oceanic, Olympic. The name was shelved, only to be reused 12 years later. His health improved for a brief time, allowing him to visit Oceanic upon her completion in Belfast that July. During his visit, Belfast officials awarded him with a key to the city, citing his contributions to the local economy and to British merchant shipping. Unfortunately, in late August he took a turn for the worse and he underwent two operations to alleviate his ailment, both of which proved unsuccessful, and Thomas suffered a heart attack on 14 September. He lingered in worsening agony for another ten weeks until his death on 23 November 1899 at the age of 62. In the immediate aftermath, control of the company was passed to Thomas' son Bruce, who was named chairman of the line.[22]

"The Big Four"

Even before Oceanic had been completed, White Star had already started making plans for a considerably larger addition to their fleet. In September 1898, before his health began failing, Thomas Ismay negotiated the terms for the orders for the last passenger liner he would ever order for the line he'd built. This time around, plans were essentially the same as they had been with Oceanic, only taking considerable more steps in innovation. While staying with the trend in focusing more on comfort than speed as had been set with Cymric and Oceanic, Ismay's plans called for a new passenger liner of dimensions the world had never seen, and her chosen name was to be Celtic, a name taken and reused from the original Oceanic class. The initial designs for Celtic had her at 680 feet in length, a tad bit shorter than Oceanic, but with a greater breadth of her predecessor at 75 feet. Additionally, while the Oceanic had set the record for length, Celtic would triumph in tonnage, weighing in at just over 20,000 tons.[25]

Engines

One interesting note about this new ship was in regard to her engines. Historian Mark Chirnside made a notable comparison between the machinery installed aboard Cymric and that placed in Oceanic. Because Cymric had initially been designed as a livestock carrier, she was built with smaller engines capable of modest speeds which both consumed less coal and occupied less space within the hull. As a result, there was an astonishing difference which gave Cymric a considerable advantage over Oceanic. Although Cymric was overall only about two-thirds the size of Oceanic in terms of gross tonnage (12,552 to 17,274), her net tonnage, a unit of measurement used to account for space aboard a ship usable for passengers and cargo was actually greater than what was seen in the larger vessel (8,123 net tons aboard Cymric compared to only 6,996 with the Oceanic). According to Chirnside, builders and designers used this as a baseline for engine designs for Celtic.[26] She was to be equipped with quadruple expansion engines geared to twin screws capable of considerably modest speeds of just over 16 knots. Because she was geared to set lower service speeds, her coal consumption was far less at only 260 tons per day, which compared to the 400 tons per day needed to power Oceanic made her much more economical.[27] At the same time, owing to her broad hull, she was designed with cargo holds capable of storing up to 18,500 tons of commercial cargo, a strategic placement in her design as that cargo was to serve as ballast, keeping her steady in even the roughest seas.[26]

Capacities

Additionally, Celtic was to be designed with far greater capacities for both passengers and cargo. Her plans called for accommodations for a staggering 2,859 passengers: 347 in First Class, 160 in Second Class, and a total of 2,352 in Third Class, the latter being largest capacity seen of any liner on the North Atlantic at the time. Passenger accommodations were spread across six decks, titled from top to bottom: Boat Deck (A Deck), Upper Promenade (B Deck), Promenade (C Deck), Saloon (D Deck), Upper (E Deck) and Lower (F Deck). First Class accommodations were located amidships on the uppermost four decks and included a lounge and smoke room on the Boat Deck, as well as a grand and spacious dining room on the Saloon Deck. Second Class accommodations were allocated to the starboard sides of the Saloon and Upper Decks. Like as seen aboard Teutonic, Majestic, and Oceanic, Second Class passengers were provided with their own smoke room and library, housed within a separate deckhouse situated just aft of the main superstructure, directly beneath which on the Saloon Deck was located their dining room.[28]

What made Celtic rather exceptional for the time was her Third Class accommodations, which in addition to ample open deck space on the Promenade Deck, were located on the Saloon, Upper and Lower Decks at both the forward and aft ends of the vessel, with a vast majority being located aft. The pattern followed that as was seen on all White Star vessels on the North Atlantic, with single men berthed forward, and single women, married couples and families berthed aft. On the Saloon Deck, in addition to baths and lavatories both forward and aft, were located two large dining rooms at the far after end of the deck, situated side by side, which when meals weren't being served respectively functioned as smoke and general rooms. An additional, fairly larger dining room was located directly beneath these on the Upper Deck, while a fourth dining room was located forward where single men were to be berthed, for which this dining room was equipped with a service bar. Aside from this, the biggest change brought by the Celtic for Third Class passengers was in sleeping quarters. In these days, open berths were still fairly common on the North Atlantic, which White Star had from the start gradually shied away from. Aboard the Oceanic class liners, Britannic and Germanic, steerage passengers had been provided with large rooms which generally slept around 20 people, while aboard Teutonic and Majestic the usage of two and four berth cabins had been introduced, but only for married couples and families with children, a policy which also held with Cymric and Oceanic. Celtic broke that mould. At the forward end of the vessel, located in two compartments on the Lower Deck were accommodations of the older style of sleeping arrangements, each compartment providing for 300 single men. The remaining 1,752 berths were located aft, all of which consisted of two, four and six berth cabins.[29]

Construction

On 22 March 1899, just two months after Oceanic was launched, the first keel plates of the Celtic were laid at Harland & Wolff. Construction progressed on her rapidly, and as White Star had planned, the new fleet of liners would be constructed in overlapping succession, as in October 1900, while Celtic's hull was nearing completion, construction began on the second ship, Cedric. When Celtic was launched in April 1901, there was much fanfare, as she was hailed the largest ship in the world in terms of tonnage, as well as being the first to exceed the tonnage of the infamous Great Eastern. She took a mere four additional months for fitting out before sailing on her maiden voyage from Liverpool on 26 July of that year.[30] Upon her entry into service, one of her most attractive features was her seaworthiness, as on her maiden voyage it was noted how while at sea, she was "as steady as the Rock of Gibraltar."[31]

Meanwhile, construction on Cedric had proceeded as planned and she was launched on 21 August 1902. Although she was of exactly the same dimensions as Celtic in length and width, she outweighed her twin by a mere 155 tons, making her now the largest ship in the world. Despite their similarities, the two had distinct differences. Aboard Cedric, First Class accommodations included more private bathrooms as well as more suites consisting of interconnecting cabins provided with sitting rooms.[32] In all, she had accommodations for 2,600 passengers, with a slightly increased number of First Class passengers at 350, her Second Class capacity was increased to 250, while Third Class was scaled back to approximately 2,000. Cedric entered service later that winter, departing Liverpool on her maiden voyage on 11 February 1903.[33]

The keel of the third sister, Baltic had been laid down at Harland & Wolff in June 1902, while construction on Cedric was still underway. One notable instance in her construction was once her keel was fitted in place, White Star gave orders for her length to be extended by 28 feet. This change in plans required builders to cut her keel in two, move the after end backwards and install the new addition in between. Their reasons for this addition was likely to provide more spaces for passenger accommodations, which combined added up to 2,850 passengers Although Baltic was designed with the same layout for Third Class passengers as Cedric, with a capacity of 2,000, her First and Second Class capacities were significantly greater. First Class was increased to a capacity for 425 passengers, while capacity for Second Class was extended to 450 passengers, almost twice that of Cedric and three times that of Celtic. Simultaneously, the added length also increased her gross tonnage to 23,884, making her now the largest ship in the world. Baltic was launched on 12 November 1903, subsequently fitted out and delivered to White Star on 23 June 1904, and sailed on her maiden voyage on 29 June.[34]

While the first three members of the highly regarded quartet of liners were built and put into service with little problems, the fourth and final ship, Adriatic, experienced a considerable delay in her construction. Initially, her construction had commenced in November 1902 while Baltic was still being built, but a series of delays slowed her construction to a snail's pace as compared to that of her sisters. For example, the timeline of construction on Baltic between the laying of her keel and her launch was roughly 17 months. By the time Adriatic was finally launched in September 1906, she'd been under construction for almost 46 months, more than twice the time needed to construct her twin.[35] In her design, her passenger accommodations followed the same trend as seen with Baltic, with added focus on the upper two classes while still maintaining the high standard for Third Class. Her overall passenger capacity was also identical to that of Baltic at 2,850, but with differences in capacities for each class, with First Class increased to 450, Second Class increased to 500 and Third Class scaled back to 1,900. Unlike her sisters however, she was unable to attain the title of world's largest ship at the time of her completion, as her 24,451 gross tonnage was just barely outmatched by Hamburg Amerika's Kaiserin Auguste Victoria, which measured at 24,581 tons and entered service four months prior to the launch of Adriatic. She would, however, rank briefly as the largest British-built ship until Cunard's famous greyhound Lusitania came into service the following year.[36] She sailed on her maiden voyage to New York on 8 May 1907, and not long afterwards gained a considerable reputation for her interiors, enough for the British tabloid The Bystander to dub her 'The Liner Luxurious'. One of her most notable innovations was that she was the first liner to have an onboard Turkish Bath and swimming pool.[37]

Intermediate liners and rapid expansion, 1903–07

As White Star gradually brought the 'Big Four' into service, they also attained several smaller 'intermediate' liners in preparation for a considerable expansion of their passenger services on the North Atlantic. In 1903 alone they came to obtain five new liners, beginning with Arabic. Originally laid down as Minnewaska for the Atlantic Transport Line, she was transferred to White Star prior to completion and was launched under her new name on 18 December 1902. Similar in size and appearance to Cymric with a single funnel and four masts, she measured at 600 feet in length with a beam of 65 feet, weighing in at 15,801 gross tons with quadruple expansion engines geared to twin screws capable of a service speed of 16 knots. She was fitted with fairly modest accommodations for 1,400 passengers: 200 in First Class, 200 in Second Class and 1,000 in Third Class. She sailed on her maiden voyage out of Liverpool to New York on 26 June 1903.

Meanwhile, as a result of the IMMCo. takeover under J. Pierpont Morgan, White Star obtained four newly completed liners in the last months of 1903, they being the Columbus, Commonwealth, New England and Mayflower. These four liners had been owned and operated by the Dominion Line for their services between Liverpool and Boston as well as their Mediterranean cruising and emigrant route, which also connected to Boston. However, the Dominion Line was also absorbed into the IMM scheme and the four ships were transferred to White Star. In addition to the acquisition of these ships, White Star also acquired control of the routes as well. Upon their acquisition by White Star, the four liners were respectively renamed Republic, Cretic, Romanic and Canopic. These four ships were greatly similar in appearance to the Cymric and Arabic, all with a single funnel with two or four masts, with engines geared to twin screws capable of service speeds between 14 and 16 knots. They all also fell within the same range in terms of dimensions, with lengths between 550 and 582 feet, beams between 59 and 67 feet, and gross tonnage as follows, Republic at 15,378 tons, Cretic 13,518 tons, Romanic at 11,394 tons and Canopic at 12,097 tons. There was, however, considerable variances in passenger capacities. Republic, which in time would come to obtain the nickname 'The Millionaires' Ship', had the largest capacity with accommodations for 2,400 passengers (200 First Class, 200 Second Class, 2,000 Third Class). The three remaining ships had considerably smaller capacities, with the Cretic designed with accommodations for 1,510 passengers (260 First Class, 250 Second Class, 1,000 Third Class), Romanic with accommodations for 1,200 passengers (200 First Class, 200 Second Class, 800 Third Class) and Canopic with accommodations for 1,277 passengers (275 First Class, 232 Second Class, 770 Third Class).[38]

Following the conclusion of their service under Dominion in the late fall of 1903, the four liners were briefly withdrawn from service, their names redone, funnels repainted in White Star colors, and made ready for their new services. Romanic was the first to enter service under White Star, sailing for Boston on 19 November, followed by Cretic on 26 November. In order to balance the schedule between the Liverpool and Mediterranean services to Boston, Cymric was transferred to the Liverpool-Boston route, departing Liverpool for her first trip to Boston on 10 December, while Republic entered service to Boston on 17 December. Canopic completed the service upon her departure from Liverpool on 14 January 1904. Upon their arrivals in Boston, Romanic and Canopic were both immediately transferred to the Mediterranean services formerly upheld by the Dominion Line. This route followed a line which first made port at Sao Miguel in the Azores before passing through the straits of Gibraltar and making port in Naples and Genoa. Republic was also put into service on the Mediterranean route following her first crossing to Boston, but only for the first half of the 1904 season, as come summer she was switched back to the Liverpool-Boston service until winter, a pattern of divided seasons between the North Atlantic and Mediterranean routes which she would follow for the remainder of her career. Cretic remained on the Liverpool-Boston service running opposite Cymric for a full year until November 1904, when alongside Republic she began sailing on a secondary service to the Mediterranean from New York.[38]

In the early months of 1907, White Star began preparations for another extension of their services on the North Atlantic by establishing an 'Express' service to New York. The new service would depart Southampton every Wednesday, first heading south across the English Channel to the French port of Cherbourg that evening, then sailing back across the channel to Queenstown the following morning before proceeding to New York. On eastbound crossings, ships would forego calling at Queenstown and make port at Plymouth, before proceeding to Cherbourg and Southampton. Because of its proximity to London, Southampton had a clear advantage over Liverpool in reducing travelling time, while by creating a terminal at Cherbourg White Star had established a route which allowed passengers to embark or disembark at either a British or Continental port.[39] Another subsidiary of IMM, the American Line, had moved their operations to Southampton in 1893 and established an express service via Cherbourg which had proved very successful, thus prompting White Star to make a similar move.[40] Celtic embarked on two experimental crossings from Southampton to New York via Cherbourg and Queenstown, first on 20 April and then again on 18 May, which proved successful and set the way for the establishment of the route, which was to be maintained by Teutonic, Majestic, Oceanic and the newly completed Adriatic. Celtic was returned to the Liverpool service after the second crossing, and her place taken on the new run by Adriatic, which sailed from Southampton for the first time on 5 June, followed by Teutonic on 12 June, Oceanic on 19 June and Majestic on 26 June.

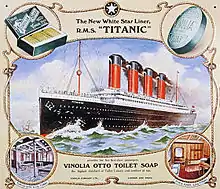

Olympic class ships

The Cunard Line was the chief competitor to White Star. In response to Cunard's Lusitania and Mauretania, White Star ordered the Olympic class liners: Olympic, Titanic and Britannic. While Cunard was famed for the speed of their ships, the Olympic class were to be the largest and most luxurious ships in the world. Olympic, however, was the only ship of this class to have a successful career. Titanic sank on her maiden voyage in April 1912, while Britannic was requisitioned by the British government while she was still being fitted out, and was used as a hospital ship during World War I. Britannic hit an underwater mine in the Kea Channel and sank on the morning of 21 November 1916.[41]

First World War

Like many other shipping lines, the White Star Line suffered heavy losses during the First World War which began in August 1914, including some of their most prestigious vessels. The first major war loss was of RMS Oceanic of 1899, which was converted into an armed merchant cruiser and ran aground near the Shetland Islands due to navigational error in September 1914. The first White Star ship lost to enemy action was the liner Arabic which was torpedoed off the Irish coast in August 1915 with the loss of 44 lives.[42]

1916 would see the largest loss of the war, Titanic's sister ship Britannic which was sunk near the Greek island of Kea in May after striking a naval mine, while in service as a hospital ship. Britannic was the largest loss for the company, and also the largest ship sunk during the conflict. 1916 also saw the loss of the liner Cymric which was torpedoed off the Irish coast in May, and also of the cargo ship Georgic, which was scuttled in December with its cargo of 1,200 horses still on board, after being intercepted in the Atlantic by the German merchant raider SMS Möwe.[42]

1917 saw the loss of the liner Laurentic in January which struck a mine off the Irish coast and sank with the loss of 354 lives and 3,211 gold ingots. The following month the liner Afric was sunk by a torpedo in the English Channel, as was the liner Delphic in August.[42]

Many White Star vessels were requisitioned for various types of war service, most commonly for use as troop ships, the most notable of these was the RMS Olympic which transported over 200,000 troops during the conflict.[43][42]

Interwar years

The losses of the Titanic and Britannic left Olympic as the only surviving member of White Star's planned trio of express liners. In 1922 the White Star Line obtained two former German liners which had been ceded to Britain as war reparations under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, ostensibly as replacements for the war losses of Britannic, Oceanic, Arabic, Cymric and Laurentic: The former SS Bismarck which was renamed Majestic, and the former SS Columbus which was renamed Homeric. At 56,551 gross tons, Majestic was then the world's largest liner and became the company's flagship. The two former German liners operated successfully alongside Olympic for an express service on the Southampton–New York route until the Great Depression reduced demand after 1930.[42]

In the immediate post-war period there was a boom in the transatlantic emigrant trade, from which White Star was able to benefit for a time, however this trade was badly affected by the American Immigration Act of 1924 which introduced quotas for immigrants to the United States. This hit the profits of the shipping lines, for whom the emigrant trade had been a staple for nearly a century. However the growth in tourism was to some degree able to offset the decline of the emigrant trade, and White Star made efforts to appeal to this new breed of traveller by gradually overhauling liners still in service and re-configuring Third Class accommodations as Tourist Class.[42]

In 1927 the White Star Line was purchased by the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company (RMSPC), making RMSPC the largest shipping group in the world.[44][45]

In 1928 a new Oceanic (III) was proposed and her keel was laid down that year at Harland and Wolff. The thousand foot long liner was to have been a motor ship propelled by the new diesel-electric propulsion system, but the ship was never completed due to financial issues. Oceanic's keel was dismantled and the steel was used in two new smaller motor ships: Britannic (III) and Georgic (II). Both of these ships entered service by 1932; they were the last liners White Star had built.

RMSPC ran into financial trouble, and was liquidated in 1932. A new company, Royal Mail Lines Limited, took over the ships of RMSPC and their subordinate lines including White Star.[46]

Cunard merger

In 1933 White Star and Cunard were both in serious financial difficulties because of the Great Depression, falling passenger numbers and the advanced age of their fleets. Work was halted on Cunard's new giant, Hull 534 ,later the Queen Mary, in 1931 to save money. In 1933 the British government agreed to provide assistance to the two competitors on the condition that they merge their North Atlantic operations. The agreement was completed on 30 December 1933.

The merger took place on 10 May 1934, creating Cunard-White Star Limited. White Star contributed ten ships to the new company while Cunard contributed 15 ships. Because of this, and since Hull 534 was Cunard's ship, 62% of the company was owned by Cunard's shareholders and 38% of the company was owned for the benefit of White Star's creditors. White Star's Australia and New Zealand services were not involved in the merger, but were separately disposed of to Shaw, Savill & Albion later in 1934. A year after this merger, Olympic, the last of her class, was removed from service. She was scrapped in 1937.

In 1947 Cunard acquired the 38% of Cunard White Star they did not already own, and on 31 December 1949 they acquired Cunard-White Star's assets and operations, and reverted to using the name "Cunard" on 1 January 1950. From the time of the 1934 merger, the house flags of both lines had been flown on all their ships, with each ship flying the flag of its original owner above the other, but from 1950, even Georgic[47] and Britannic,[48] the last surviving White Star liners, flew the Cunard house flag above the White Star burgee until they were each withdrawn from service, in 1956 and 1961 respectively. Just as the retiring of Cunard Line's Aquitania in 1950 marked the end of the era of the classic pre-World War I 'floating palaces', and also the end of Cunard-White Star, so the retirement of the Britannic a decade later had marked the end of an era for White Star as a visible brand.[49] All other ships flew the Cunard flag over the White Star flag until late 1968. This was most likely because Nomadic remained in service with Cunard until 4 November 1968, and was sent to the breakers' yard, only to be bought for use as a floating restaurant.

The Australia Run

White Star had begun as a line serving traffic to and from Australia, especially during the gold rushes of the 1850s, but following the line's collapse and its purchase by Thomas Ismay in 1868 the company was rebuilt as a trans-Atlantic line. However, in the late 1890s White Star decided to reinstate a service to Australia, partly because of the discovery of further gold deposits in Western Australia leading to another series of gold rushes and an increased traffic in emigrants to Australia, while there was also an increasing trade in minerals, agricultural produce, wool and meat in the other direction. The latter had become a major source of revenue for shipping lines already on the route after the advent of effective mechanical refrigeration systems in the late 1880s, allowing large quantities of cattle carcasses to be preserved on the long voyage back to the British Isles.

Thomas Ismay decided to re-enter the Australian run in 1897 with a monthly service between Liverpool, Cape Town and Sydney. A stop at Tenerife was included in the schedule both outbound and inbound. Outbound ships would call at Adelaide and Melbourne and the return trip would call at Plymouth before ending at Liverpool. With that route taking six weeks, five ships would be needed to maintain the service in both directions. The specification for the new ships was drawn up and the order placed with Harland & Wolff in the summer of 1897, coinciding with the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, thus they became known as the Jubilee-class ocean liners.[50] In keeping with White Star's new philosophy on the Atlantic of size over speed, the Jubilee-class were to be the largest ships ever put on the Australia run, at 550 ft (168 metres) in length and nearly 12,000 gross tons. They were single-funnel, twin-screw ships designed as mixed cargo/passenger vessels, being in essence enlarged versions of White Star's Naronic-class ships.[51] With a service speed of 14 knots the Jubilee-class were significantly slower than the smaller mailships run by the Orient Line and P&O. Their size meant they could not transit the Suez Canal and would have to take the long route via South Africa so would not attract first-class passengers. Instead they were intended for the emigrant/seasonal worker traffic, carrying 320 passengers solely in what was described as third-class accommodation. However, following White Star's long tradition of improving standards for third-class passengers, these facilities were considerably ahead of the equivalent on other lines, being broadly in line with second-class facilities on other ships. Although all of the same class, prices for berths on the Jubilee-class varied, allowing passengers the choice of two- or four-berth cabins for a premium or open dormitories. Passengers had use of facilities such as a large dining room, a library and a smoking room, as well as free run of nearly all the ship's deck space during the voyage. The ships could carry 15,000 tons of cargo in seven holds, including capacity for 100,000 meat carcasses.[52]

.jpg.webp)

The first Jubilee-class ship, Afric, was launched in November 1898, but her maiden voyage in February 1899 was to New York as a shakedown cruise and to test the new ship on a shorter route – small improvements were made to Afric and her sisterships in-build as a result of this trip.[50] The Australian service was actually inaugurated by the second ship, Medic, which left Liverpool in August 1899 and arrived in Sydney in October.[52] The third ship, Persic, began her maiden voyage in December 1899 but was delayed for several weeks in Cape Town after her rudder broke due to faulty metalwork in her rudder stock. The final pair of ships for the Australia run were to a modified design following the experiences with the original trio. The Australia Run proved to be more popular with passengers than expected so these two ships, Runic and Suevic had their bridges moved forward and their poop decks extended.[50][51] As well as slightly increasing their gross tonnage this gave them capacity for a further 50 passengers, bringing the total to 400. Suevic made her maiden voyage in May 1901, bringing White Star's new Australian service to full strength. By now the return voyage also included a stop at London – most passengers from Australia disembarked at Plymouth, to go to their final destination by railway, while much of the cargo was bound for London. The ship would then steam back through the English Channel to offload the last of her cargo and passengers at Liverpool before preparing for the next voyage.

.jpg.webp)

The Australian Run was successful and profitable for White Star, and largely uneventful for the ships. In the earliest days of the route the initial three ships were heavily used to transport men, soldiers and supplies to South Africa during the Boer War, while Suevic ran aground off Lizard Point, Cornwall in dramatic fashion in 1907, but there were no casualties and, despite the ship being broken in two, she was repaired and reentered service in January 1908.[51] The success of the new Australian service in terms of freight led to White Star transferring an older cargo-only ship of a similar size to the Jubilee-class, the Cevic, from the New York service to the Australia Run. In 1910 Cevic was used to experiment with routing ships to Australia via the Suez Canal but she ran aground several times in the canal and the ships remained on the route via the Cape. Cevic was used on the Australia Run on a seasonale basis, mainly carrying cattle and wool at the end of the Australian autumn (February–April) and then being switched to the New York Run during the Atlantic summer.

Continued demand for extra passenger capacity led to White Star building a one-off ship for the route. Launched in 1913, Ceramic was a larger, more sophisticated development of the Jubilee-class, at 655 feet (200 metres) in length and 18,495 gross tons. Like the Laurentic and the Olympic-class, Ceramic was a triple-screw ship with the central propeller driven by a low-pressure turbine using exhaust from the two recriprocating steam engines. This enabled her to be slightly faster – 16 knots – than the Jubilee-class vessels despite her extra size for a minimal increase in coal consumption. The new ship had a significantly larger superstructure and nearly double the passenger capacity of the Jubilee-class ships – a total of 600 passengers, still carried only in what was advertised as third-class accommodation. She could also carry 19,000 tons cargo in eight holds, including 321,000 cubic feet of refrigerated space.[53] The dimensions of Ceramic were restricted by the length of the quay at London's Port of Tilbury and the clearance for the masts under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. When she arrived in Sydney in September 1914 she took the place of the Jubilee-class ships as the largest vessels put on the Australia Run from Britain and became the tallest ship to pass under the bridge.[53]

All seven ships were requisitioned as troop transports during the World War I, forcing White Star to suspend the regular Australia service. Afric was torpedoed by a U-boat in the English Channel in 1917 and Cevic remained in the ownership of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary after the war but the other five ships were returned to White Star and the service was resumed in 1919. The remaining Jubilee-class liners were withdrawn from White Star service in the late 1920s. Persic was scrapped in 1926 while the other three were sold in 1928 (Medic and Suevic) and 1929 (Runic). All were converted into whaling factory ships on account of their size and cargo capacity. The Australia Run was no longer so lucrative or as heavily-trafficked as it had been before the war and the route was no longer a priority for White Star, especially once it came under the ownership of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company in 1927. A new ship, intended to be the first of a new class to replace the Jubilee-class, had been launched in 1917 - the Vedic. This was the first White Star Line ship to be powered solely by turbines and had the same emigrant/cargo-carrying role as her predecessors, although at 460 feet (140 metres) and 9,332 gross tons she was smaller than the older ships. Vedic went straight from the builders to service as a troopship and was initially used on White Star's Canadian service until she was put on the Australia Run in 1925. Between them Ceramic and Vedic maintained a less-intensive Australian service until their owners merged with the Cunard Line. The new management immediately decided to end White Star's routes to the southern hemisphere – Ceramic was sold to Shaw, Savill & Albion Line, which continued to operate her on the same route, while Vedic was scrapped.

White Star Line today

The White Star Line's Head Offices still exist in Liverpool, standing in James Street within sight of the more grandiose headquarters of their rivals, the Cunard Building. The building has a plaque commemorating the fact that the building was the head office of the White Star Line. It was the first open plan office building in Liverpool.[54] J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the line who sailed on Titanic, had his office in the building.

The White Star Line's London offices, named Oceanic House, still exist today, and have been converted into apartments.[55] They are on Cockspur Street, off Trafalgar Square, and one can still see the name on the building over the entrances. The Southampton offices still exist, now known as Canute Chambers, they are situated in Canute Road.[56]

The French passenger tender Nomadic, the last surviving vessel of the White Star Line, was purchased by the Northern Ireland Department for Social Development in January 2006. She has since been returned to Belfast, where she has been fully restored to her original and elegant 1912 appearance under the auspices of the Nomadic Preservation Society along with the assistance of her original builders, Harland and Wolff. She is intended to serve as the centerpiece of a museum dedicated to the history of Atlantic steam, the White Star Line, and its most famous ship, the Titanic. The historic Nomadic was opened ceremoniously to the public on 31 May 2013.[57]

Cunard Line itself has, since 1995, introduced White Star Service as the brand of services on their ships RMS Queen Mary 2, MS Queen Victoria and the MS Queen Elizabeth. The company has also created the White Star Academy, an in-house programme for preparing new crew members for the service standards expected on Cunard ships.[58]

The White Star flag is raised on all Cunard ships and on the Nomadic in Belfast, Northern Ireland every 15 April in memory of the Titanic disaster.

Fleet events

- On 21 January 1854 Tayleur wrecked off Lambay Island, with the loss of 380 lives, out of 652 on board.

- In 1873 Atlantic was wrecked near Halifax, costing 535 lives.[59]

- In 1893 Naronic vanished on the Atlantic Ocean with 74 crew after departing Liverpool for New York. Wreckage found included deck spars and at least two lifeboats, but no trace of her crew. Her wreck has never been found.

- In 1907 Suevic ran aground off the southwest coast of England, but in the largest rescue of its kind, all 597 persons (456 passengers + 141 crew) were rescued. The ship was later deliberately severed in two with explosives, with the stern half being rebuilt with a new bow.

- In 1909 the Republic foundered off the New England coast after a collision with the Italian liner Florida. Four lives were lost in the collision and the ship remained afloat for over 39 hours before foundering. The remaining passengers were rescued.

- In September 1911 Olympic was involved in a collision with the warship HMS Hawke in the Solent, badly damaging both ships.

- In February 1912, Olympic lost a propeller blade on an eastbound voyage from New York after apparently striking an unknown object floating just below the surface.

- On 14–15 April 1912 Titanic was lost after colliding with an iceberg, taking upwards of 1,500 passengers and crew with her.

- The first White Star ship lost during World War I was Arabic, torpedoed off the Old Head of Kinsale Ireland on 19 August 1915 killing 44.

- In 1915 the Ionic (1902) was narrowly missed by a German torpedo in the Mediterranean Sea. No lives were lost.

- On 28 June 1915 the Armenian, a vessel built for the Leyland Line but leased to the White Star Line, was sunk by a torpedo fired by SM U-24 20 miles off the coast of Cornwall, carrying a cargo of 1,400 mules. 29 crew and all the mules were lost.

- On 3 May 1915 the former Germanic (then in service as a Turkish troop transport) was torpedoed by the British submarine HMS E14. The ship survived the attack with no fatalities.

- In May 1916 Ceramic was narrowly missed by two torpedoes from unidentified U-boat in Mediterranean Sea.

- In 1916 the Cymric was torpedoed three times and sunk off the southern coast of Ireland by U-20, noted as the same submarine responsible for the tragic sinking of the Lusitania the year before. Five lives were lost and the ship stayed afloat for almost three days before foundering.

- On 21 November 1916, the second sister ship of Titanic, HMHS Britannic, was lost after striking a mine laid by U-73[60] in the Kea Channel of the Aegean Sea off the coast of Greece. It sank in 57 minutes with the loss of 30 lives and was the largest vessel sunk in the war.

- On 25 January 1917 Laurentic struck two mines laid by U-80 and sank with a loss of 354 lives.

- In May 1917 Afric was torpedoed and sunk by UC-66, in English Channel, killing 22 crew members.

- In June 1917 Ceramic was narrowly missed by one torpedo from unidentified U-boat in English Channel.

- In August 1917 Delphic was torpedoed 135 miles off Bishop Rock by German U-boat UC-72 and sank with the loss of five lives.

- In October 1917 RMS Celtic ran up on a mine laid by U-88 near Cobh, Ireland, killing 17. She was repaired and put back into military service. In June 1918, she was torpedoed by UB-77 in the Irish Sea, killing seven. Once again, she was able to escape the sub and limp into port with her own steam. She was repaired and once again put back into service, serving through the remainder of the war without incident.

- On 12 May 1918, Olympic rammed and sank the U-boat U-103 which had tried, and failed, to torpedo it. However, several bow plates on Olympic were dented from the collision with the U-boat. Later, while Olympic was in Dry Dock, a large circular-shaped dent was found in the side of her hull, appearing to be the same size as the head of the standard torpedoes used by the German U-boats.

- On 19–20 July 1918 Justicia (owned by the British Government and managed by White Star) was torpedoed twice by U-46 but she remained afloat. Later in the same day, she was torpedoed two more times by U-46 and again managed to stay afloat. The next morning, as she was towed by HMS Sonia, she was torpedoed two more times by SM U-124 (2) and finally sank, killing 16 crew members.

- In September 1918 Persic was torpedoed by U-87 off of the Isles of Scilly, but was able to limp off and outrun the sub. She was towed in and repaired, resuming service.

- On 3 October 1932 Laurentic collided with Lurigethen of the HE Moss Line. Both vessels remained afloat following the collision.

- On 15 May 1934, while steaming in a fog, Olympic rammed the Lightship Nantucket, sinking it and killing seven of the crew.

- On 18 August 1935 Laurentic collided with Napier Star of the Blue Star Line, leaving six dead among the crew of Laurentic.

- In November 1940 Laurentic was torpedoed and sunk by U-99 off Northern Ireland with the loss of 49 lives.

Notable captains

- Commodore Sir Bertram Fox Hayes KCMG DSO RD RNR – Commodore, White Star Line

- Captain Digby Murray, Commodore, best known as captain of Republic and Atlantic.[61]

- Captain J. B. Ranson OBE of Baltic.[62]

- Captain Edward J. Smith RD RNR of Titanic.

- Captain Charles Bartlett CB CBE RD RNR of Britannic, one of the sister ships of Titanic.[63]

- Captain Herbert J. Haddock CB RNR of the Oceanic, Olympic,[64] and – for a few days before her departure – Titanic.

Fleet

See also

References

- "The Legendary Cunard White Star Service". The Cunarders. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- Bourke, Edward J (2003). Bound for Australia. p. 18. ISBN 0-9523027-3-X.

- https://newspapers.library.wales/view/4351712/4351713/1/

- https://newspapers.library.wales/view/4511187/4511190/24/Silistria

- http://www.tynebuiltships.co.uk/R-Ships/royalstandard1863.html

- "White Star Line". Gracesguide.co.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Barczewski, Stephanie (2006). Titanic: A Night Remembered. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 213. ISBN 1-85285-500-2. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". pp. 11–12.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". pp. 17, 20, 22–23.

- Greg Cochkanoff and Bob Chaulk, SS Atlantic: The White Star Line's First Disaster at Sea, (Goose Lane Editions, Fredericton, 2009) p. 99.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". pp. 25–30.

- Blue Riband#List of record breakers

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". pp. 19, 22, 24.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". pp. 45, 51.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". p. 46.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". pp. 17, 19.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". p. 24.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". p. 65

- Chirnside, Mark. 'The Big Four of the White Star Line'. pp. 9–10.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". p. 81.

- The Titanic Commutator: Vol II, Issue 23, Fall 1979: pp. 4–5.

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". pp. 81–82.

- The Titanic Commutator: Vol II, Issue 23, Fall 1979: pp. 7, 9–10.

- https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/SS_Celtic

- Chirnside, Mark. "The 'Big Four' of the White Star Fleet". pp. 10–11, 13.

- Gardiner, Robin. "The History of the White Star Line". p. 121.

- Chirnside, Mark. "The 'Big Four' of the White Star Fleet". pp. 13, 20

- Chirnside, Mark. "The 'Big Four' of the White Star Fleet". pp. 13, 20.

- Chirnside, Mark. "The 'Big Four' of the White Star Fleet". pp. 10, 15–20.

- "The Titanic Commutator", Volume VII, Issue II, Summer 1983. "The Big Four of the White Star, Part 1", p. 7

- Chirnside, Mark. "The 'Big Four' of the White Star Fleet". p. 33

- "The Titanic Commutator", Volume VII, Issue II, Summer 1983. "The Big Four of the White Star, Part 1", p. 9

- "The Titanic Commutator", Volume VII, Issue II, Summer 1983. "The Big Four of the White Star, Part 1", pp. 13–15.

- Chirnside, Mark. "The 'Big Four' of the White Star Fleet". p. 54

- "The Titanic Commutator", Volume VII, Issue II, Summer 1983. "The Big Four of the White Star, Part 1", pp. 16–17.

- Chirnside, Mark. "The 'Big Four' of the White Star Fleet". p. 61

- De Kerbrech, Richard. "Ships of the White Star Line". pp. 113–118.

- Chirnside, Mark. "The 'Big Four' of the White Star Fleet". p. 66

- Flayhart, William H. "The American Line: 1871–1902". p. 139.

- "Britannic sinks in Aegean Sea – Nov 21, 1916". History.com. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Kerbrech, Richard De (2009). Ships of the White Star Line. Ian Allan Publishing. pp. 181–183. ISBN 978-0-7110-3366-5.

- Chirnside, Mark (2011). The 'Olympic' Class Ships. The History Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-7524-5895-3.

- "Fact file – PortCities Southampton". Plimsoll.org. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- "The Royal Mail Story: The Kylsant years". Users.on.net. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- "The Royal Mail Story: Royal Mail Lines, Ltd". Users.on.net. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- "Georgic". Chris' Cunard Page. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- "Britannic". Chris' Cunard Page. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- Anderson, Roy (1964). White Star. Prescot, England: T. Stephenson & Sons Ltd. p. 181.

- Kerbrech, Richard De (2009). Ships of the White Star Line. Ian Allan Publishing. pp. 78–89. ISBN 978-0-7110-3366-5.

- Haws, Duncan (1990). White Star Line (Oceanic Steam Navigation Company). pp. 50–54. ISBN 0-946378-16-9.

- "A Mammoth Steamship. The New White Star Liner. Arrival of the Medic". The North Queensland Register. IX (43). Queensland, Australia. 2 October 1899. p. 25. Retrieved 10 September 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- Hardy, Clare (2006). SS Ceramic, The Untold Story. pp. 19–20. ISBN 1-904908-64-0.

- "Liverpool's old White Star Line building reborn as a luxury Titanic styled hotel". Lancashirelife.co.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Titanic's London HQ to be turned into luxury flats". Standard.co.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Canute Chambers". Daily Echo. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "SS Nomadic restored as a major maritime tourism attraction - Heritage Lottery Fund". Hlf.org.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "White Star Service – Cunard Cruise Line". Cunard.

- Greg Cochkanoff and Bob Chaulk, SS Atlantic: The White Star Line's First Disaster at Sea, (Goose Lane Editions, Fredericton, 2009) p. 163.

- "Hospital ship Britannic – Ships hit by U-boats – German and Austrian U-boats of World War One – Kaiserliche Marine". uboat.net.

- Love, Bob (2006), "Sixth Day", Destiny's Voyage: SS Atlantic, the Titanic of 1873, AuthorHouse, pp. 256–257, ISBN 1425930395

- "Lot 537, 23 June 2005 - Dix Noonan Webb". Dnw.co.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- https://www.history.co.uk/this-day-in-history/21-november/britannic-sinks-in-aegean-sea

- https://www.birminghammail.co.uk/news/local-news/titanic-100-years-on-how-183184

Further reading

- The ship's list

- History of the White Star Line

- Red duster page on the White Star Line

- Brief company overview

- Info on the original financing deal

- Chirnside, Mark (2016). The 'Big Four' of the White Star Fleet: Celtic, Cedric, Baltic & Adriatic. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 9780750965972.

- Gardiner, Robin, History of the White Star Line, Ian Allan Publishing 2002. ISBN 0-7110-2809-5

- Oldham, Wilton J., The Ismay Line: The White Star Line, and the Ismay family story, The Journal of Commerce, Liverpool, 1961

- "A Nice Quiet Life" by Alfred H Burlinson, an engineer who served on the Olympic, the Megantic, and Britanic

External links

![]() Media related to White Star Line at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to White Star Line at Wikimedia Commons

- White Star Line on Titanic-Titanic.com

- Final Demise of White Star Line Vessels

- Brief history of the White Star Line – from TDTSC MN

- White Star Line discussion forum at TDTSC

- White Star Line Historical Documents, Brochures, Menus, Passenger Lists etc. GG Archives

- White Star Line History website

- Cunard-White Star Line on Chris' Cunard page

- Documents and clippings about White Star Line in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW