Empedocles

Empedocles (/ɛmˈpɛdəkliːz/; Greek: Ἐμπεδοκλῆς [empedoklɛ̂ːs], Empedoklēs; c. 494 – c. 434 BC, fl. 444–443 BC)[7] was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas,[8][9] a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the four classical elements. He also proposed forces he called Love and Strife which would mix and separate the elements, respectively.

Empedocles | |

|---|---|

Empedocles, 17th-century engraving | |

| Born | c. 494 BC[1] |

| Died | c. 434 BC[1] (aged around 60) unknown[lower-alpha 1] |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Pluralist school |

Main interests | Cosmogenesis, ontology, epistemology |

Notable ideas | All things[3] are made up of four elements: fire, air, earth and water Change and motion[4] are due to the corporeal substances[5] Love[6] (Aphrodite)[6] and Strife[6] The sphere of Empedocles Theories about respiration (the clepsydra experiment) Emission theory of vision |

Influences

| |

Influenced by Pythagoras (died c. 495 BC) and the Pythagoreans, Empedocles challenged the practice of animal sacrifice and killing animals for food. He developed a distinctive doctrine of reincarnation. He is generally considered the last Greek philosopher to have recorded his ideas in verse. Some of his work survives, more than is the case for any other pre-Socratic philosopher. Empedocles' death was mythologized by ancient writers, and has been the subject of a number of literary treatments.

Life

Empedocles (Empedokles) was a native citizen of Akragas in Sicily.[8][9] He came from a rich and noble family.[8][10][11] Very little is known about his life. His grandfather, also called Empedokles, had won a victory in the horse-race at Olympia in [the 71st Olympiad] OL. LXXI (496–95 BC).[8][9][10] His father's name, according to the best accounts, was Meton.[8][9][10]

All that can be said to know about the dates of Empedocles is, that his grandfather was still alive in 496 BC; that he himself was active at Akragas after 472 BC, the date of Theron’s death; and that he died later than 444 BC.[7]

Empedocles "broke up the assembly of the Thousand. perhaps some oligarchical association or club."[12] He is said to have been magnanimous in his support of the poor;[13] severe in persecuting the overbearing conduct of the oligarchs;[14] and he even declined the sovereignty of the city when it was offered to him.[15]

According to John Burnet: "there is another side to his public character ... He claimed to be a god, and to receive the homage of his fellow-citizens in that capacity. The truth is, Empedokles was not a mere statesman; he had a good deal of the 'medicine-man' about him. ... We can see what this means from the fragments of the Purifications. Empedokles was a preacher of the new religion which sought to secure release from the 'wheel of birth' by purity and abstinence. Orphicism seems to have been strong at Akragas in the days of Theron, and there are even some verbal coincidences between the poems of Empedokles and the Orphicsing Odes which Pindar addressed to that prince."[12]

His brilliant oratory,[16] his penetrating knowledge of nature, and the reputation of his marvellous powers, including the curing of diseases, and averting epidemics,[17] produced many myths and stories surrounding his name. In his poem Purifications he claimed miraculous powers, including the destruction of evil, the curing of old age, and the controlling of wind and rain.

Empedocles was acquainted or connected by friendship with the physicians Pausanias[18] (his eromenos)[19] and Acron;[20] with various Pythagoreans; and even, it is said, with Parmenides and Anaxagoras.[21] The only pupil of Empedocles who is mentioned is the sophist and rhetorician Gorgias.[22]

Timaeus and Dicaearchus spoke of the journey of Empedocles to the Peloponnese, and of the admiration, which was paid to him there;[23] others mentioned his stay at Athens, and in the newly founded colony of Thurii, 446 BC;[24] there are also fanciful reports of him travelling far to the east to the lands of the Magi.[25]

The contemporary Life of Empedocles by Xanthus has been lost.

Death

According to Aristotle, he died at the age of sixty (c. 430 BC), even though other writers have him living up to the age of one hundred and nine.[26] Likewise, there are myths concerning his death: a tradition, which is traced to Heraclides Ponticus, represented him as having been removed from the Earth; whereas others had him perishing in the flames of Mount Etna.[27]

According to Burnet: "We are told that Empedokles leapt into the crater of Etna that he might be deemed a god. This appears to be a malicious version of a tale set on foot by his adherents that he had been snatched up to heaven in the night. Both stories would easily get accepted; for there was no local tradition. Empedokles did not die in Sicily, but in the Peloponnese, or, perhaps, at Thourioi. It is not at all unlikely that he visited Athens. ... Timaios refuted the common stories [about Empedokles] at some length. (Diog. viii. 71 sqq.; Ritter and. Preller [162].). He was quite positive that Empedokles never returned to Sicily after he went to Olympia to have his poem recited to the Hellenes. The plan for the colonisation of Thourioi would, of course, be discussed at Olympia, and we know that Greeks from the Peloponnese and elsewhere joined it. He may very well have gone to Athens in connexion with this."[2]

Works

Empedocles is considered the last Greek philosopher to write in verse. There is a debate[28] about whether the surviving fragments of his teaching should be attributed to two separate poems, Purifications and On Nature, with different subject matter, or whether they may all derive from one poem with two titles,[29] or whether one title refers to part of the whole poem. Some scholars argue that the title Purifications refers to the first part of a larger work called (as a whole) On Nature.[30] There is also a debate about which fragments should be attributed to each of the poems, if there are two poems, or if part of it is called "Purifications"; because ancient writers rarely mentioned which poem they were quoting.

Empedocles was undoubtedly acquainted with the didactic poems of Xenophanes and Parmenides[31]—allusions to the latter can be found in the fragments—but he seems to have surpassed them in the animation and richness of his style, and in the clearness of his descriptions and diction. Aristotle called him the father of rhetoric,[32] and, although he acknowledged only the meter as a point of comparison between the poems of Empedocles and the epics of Homer, he described Empedocles as Homeric and powerful in his diction.[33] Lucretius speaks of him with enthusiasm, and evidently viewed him as his model.[34] The two poems together comprised 5000 lines.[35] About 550 lines of his poetry survive.

Purifications

In the old editions of Empedocles, only about 100 lines were typically ascribed to his Purifications, which was taken to be a poem about ritual purification, or the poem that contained all his religious and ethical thought. Early editors supposed that it was a poem that offered a mythical account of the world which may, nevertheless, have been part of Empedocles' philosophical system. According to Diogenes Laërtius it began with the following verses:

Friends who inhabit the mighty town by tawny Acragas

which crowns the citadel, caring for good deeds,

greetings; I, an immortal God, no longer mortal,

wander among you, honoured by all,

adorned with holy diadems and blooming garlands.

To whatever illustrious towns I go,

I am praised by men and women, and accompanied

by thousands, who thirst for deliverance,

some ask for prophecies, and some entreat,

for remedies against all kinds of disease.[36]

In the older editions, it is to this work that editors attributed the story about souls,[37] where we are told that there were once spirits who lived in a state of bliss, but having committed a crime (the nature of which is unknown) they were punished by being forced to become mortal beings, reincarnated from body to body. Humans, animals, and even plants are such spirits. The moral conduct recommended in the poem may allow us to become like gods again. If, as is now widely held, this title "Purifications" refers to the poem On Nature, or to a part of that poem, this story will have been at the beginning of the main work on nature and the cosmic cycle. The relevant verses are also sometimes attributed to the proem of On Nature, even by those who think that there was a separate poem called "Purifications".

On Nature

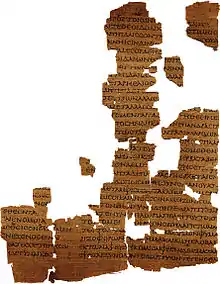

There are about 450 lines of his poem On Nature extant,[32] including 70 lines which have been reconstructed from some papyrus scraps known as the Strasbourg Papyrus. The poem originally consisted of 2000 lines of hexameter verse,[38] and was addressed to Pausanias.[39] It was this poem which outlined his philosophical system. In it, Empedocles explains not only the nature and history of the universe, including his theory of the four classical elements, but he describes theories on causation, perception, and thought, as well as explanations of terrestrial phenomena and biological processes.

Philosophy

Although acquainted with the theories of the Eleatics and the Pythagoreans, Empedocles did not belong to any one definite school.[32] An eclectic in his thinking, he combined much that had been suggested by Parmenides, Pythagoras and the Ionian schools.[32] He was a firm believer in Orphic mysteries, as well as a scientific thinker and a precursor of physics. Aristotle mentions Empedocles among the Ionic philosophers, and he places him in very close relation to the atomist philosophers and to Anaxagoras.[40]

According to House (1956)[41]

Another of the fragments of the dialogue On the Poets (Aristotle) treats more fully what is said in Poetics ch. i about Empedocles, for though clearly implying that he was not a poet, Aristotle there says he is Homeric, and an artist in language, skilled in metaphor and in the other devices of poetry.

Empedocles, like the Ionian philosophers and the atomists, continued the tradition of tragic thought which tried to find the basis of the relationship of the One and the Many. Each of the various philosophers, following Parmenides, derived from the Eleatics, the conviction that an existence could not pass into non-existence, and vice versa. Yet, each one had his peculiar way of describing this relation of Divine and mortal thought and thus of the relation of the One and the Many. In order to account for change in the world, in accordance with the ontological requirements of the Eleatics, they viewed changes as the result of mixture and separation of unalterable fundamental realities. Empedocles held that the four elements (Water, Air, Earth, and Fire) were those unchangeable fundamental realities, which were themselves transfigured into successive worlds by the powers of Love and Strife (Heraclitus had explicated the Logos or the "unity of opposites").[42]

The four elements

Empedocles established four ultimate elements which make all the structures in the world—fire, air, water, earth.[32][43] Empedocles called these four elements "roots", which he also identified with the mythical names of Zeus, Hera, Nestis, and Aidoneus[44] (e.g., "Now hear the fourfold roots of everything: enlivening Hera, Hades, shining Zeus. And Nestis, moistening mortal springs with tears").[45] Empedocles never used the term "element" (στοιχεῖον, stoicheion), which seems to have been first used by Plato.[46] According to the different proportions in which these four indestructible and unchangeable elements are combined with each other the difference of the structure is produced.[32] It is in the aggregation and segregation of elements thus arising, that Empedocles, like the atomists, found the real process which corresponds to what is popularly termed growth, increase or decrease. Nothing new comes or can come into being; the only change that can occur is a change in the juxtaposition of element with element.[32] This theory of the four elements became the standard dogma for the next two thousand years.

Love and Strife

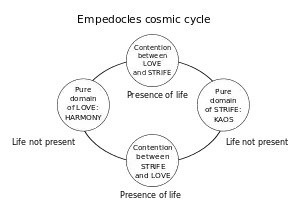

The four elements, however, are simple, eternal, and unalterable, and as change is the consequence of their mixture and separation, it was also necessary to suppose the existence of moving powers that bring about mixture and separation. The four elements are both eternally brought into union and parted from one another by two divine powers, Love and Strife (Philotes and Neikos).[32][47] Love (φιλότης) is responsible for the attraction of different forms of what we now call matter, and Strife (νεῖκος) is the cause of their separation.[48] If the four elements make up the universe, then Love and Strife explain their variation and harmony. Love and Strife are attractive and repulsive forces, respectively, which are plainly observable in human behavior, but also pervade the universe. The two forces wax and wane in their dominance, but neither force ever wholly escapes the imposition of the other.

According to Burnet: "Empedokles sometimes gave an efficient power to Love and Strife, and sometimes put them on a level with the other four. The fragments leave no room for doubt that they were thought of as spatial and corporeal. ... Love is said to be "equal in length and breadth" to the others, and Strife is described as equal to each of them in weight (fr. 17). These physical speculations were part of a history of the universe which also dealt with the origin and development of life."[5]

The sphere of Empedocles

As the best and original state, there was a time when the pure elements and the two powers co-existed in a condition of rest and inertness in the form of a sphere.[32] The elements existed together in their purity, without mixture and separation, and the uniting power of Love predominated in the sphere: the separating power of Strife guarded the extreme edges of the sphere.[49] Since that time, strife gained more sway[32] and the bond which kept the pure elementary substances together in the sphere was dissolved. The elements became the world of phenomena we see today, full of contrasts and oppositions, operated on by both Love and Strife.[32] The sphere of Empedocles being the embodiment of pure existence is the embodiment or representative of God. Empedocles assumed a cyclical universe whereby the elements return and prepare the formation of the sphere for the next period of the universe.

Cosmogony

Empedocles attempted to explain the separation of elements, the formation of earth and sea, of Sun and Moon, of atmosphere.[32] He also dealt with the first origin of plants and animals, and with the physiology of humans.[32] As the elements entered into combinations, there appeared strange results—heads without necks, arms without shoulders.[32][50] Then as these fragmentary structures met, there were seen horned heads on human bodies, bodies of oxen with human heads, and figures of double sex.[32][51] But most of these products of natural forces disappeared as suddenly as they arose; only in those rare cases where the parts were found to be adapted to each other did the complex structures last.[32] Thus the organic universe sprang from spontaneous aggregations that suited each other as if this had been intended.[32] Soon various influences reduced creatures of double sex to a male and a female, and the world was replenished with organic life.[32] It is possible to see this theory as an anticipation of Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, although Empedocles was not trying to explain evolution.[52]

Perception and knowledge

Empedocles is credited with the first comprehensive theory of light and vision. He put forward the idea that we see objects because light streams out of our eyes and touches them. While flawed, this became the fundamental basis on which later Greek philosophers and mathematicians like Euclid would construct some of the most important theories of light, vision, and optics.[53]

Knowledge is explained by the principle that elements in the things outside us are perceived by the corresponding elements in ourselves.[54] Like is known by like. The whole body is full of pores and hence respiration takes place over the whole frame. In the organs of sense these pores are specially adapted to receive the effluences which are continually rising from bodies around us; thus perception occurs.[55] In vision, certain particles go forth from the eye to meet similar particles given forth from the object, and the resultant contact constitutes vision.[56] Perception is not merely a passive reflection of external objects.[32]

Empedocles noted the limitation and narrowness of human perceptions. We see only a part but fancy that we have grasped the whole. But the senses cannot lead to truth; thought and reflection must look at the thing from every side. It is the business of a philosopher, while laying bare the fundamental difference of elements, to show the identity that exists between what seem unconnected parts of the universe.[32][57]

Respiration

In a famous fragment,[55] Empedocles attempted to explain the phenomenon of respiration by means of an elaborate analogy with the clepsydra, an ancient device for conveying liquids from one vessel to another.[58][59] This fragment has sometimes been connected to a passage in Aristotle's Physics where Aristotle refers to people who twisted wineskins and captured air in clepsydras to demonstrate that void does not exist.[60] There is however, no evidence that Empedocles performed any experiment with clepsydras.[58] The fragment certainly implies that Empedocles knew about the corporeality of air, but he says nothing whatever about the void.[58] The clepsydra was a common utensil and everyone who used it must have known, in some sense, that the invisible air could resist liquid.[61]

Reincarnation

Like Pythagoras, Empedocles believed in the transmigration of the soul/metempsychosis, that souls can be reincarnated between humans, animals and even plants.[62] For Empedocles, all living things were on the same spiritual plane; plants and animals are links in a chain where humans are a link too.[32] Empedocles was a vegetarian[63][64] and advocated vegetarianism, since the bodies of animals are the dwelling places of punished souls.[65] Wise people, who have learned the secret of life, are next to the divine,[32][66] and their souls, free from the cycle of reincarnations, are able to rest in happiness for eternity.[67]

Legend of his death and literary treatments

Diogenes Laërtius records the legend that Empedocles died by throwing himself into Mount Etna in Sicily, so that the people would believe his body had vanished and he had turned into an immortal god;[68] the volcano, however, threw back one of his bronze sandals, revealing the deceit. Another legend maintains that he threw himself into the volcano to prove to his disciples that he was immortal; he believed he would come back as a god after being consumed by the fire. Horace also refers to the death of Empedocles in his work Ars Poetica and admits poets the right to destroy themselves.[69]

In Icaro-Menippus, a comedic dialogue written by the second century satirist Lucian of Samosata, Empedocles' final fate is re-evaluated. Rather than being incinerated in the fires of Mount Etna, he was carried up into the heavens by a volcanic eruption. Although a bit singed by the ordeal, Empedocles survives and continues his life on the Moon, surviving by feeding on dew.

Empedocles' death has inspired two major modern literary treatments. Empedocles' death is the subject of Friedrich Hölderlin's play Tod des Empedokles (The Death of Empedocles), two versions of which were written between the years 1798 and 1800. A third version was made public in 1826. In Matthew Arnold's poem Empedocles on Etna, a narrative of the philosopher's last hours before he jumps to his death in the crater first published in 1852, Empedocles predicts:

To the elements it came from

Everything will return.

Our bodies to earth,

Our blood to water,

Heat to fire,

Breath to air.

In his History of Western Philosophy, Bertrand Russell humorously quotes an unnamed poet on the subject – "Great Empedocles, that ardent soul, Leapt into Etna, and was roasted whole."[70]

In J R by William Gaddis, Karl Marx's famous dictum ("From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs") is misattributed to Empedocles.[71]

In 2006, a massive underwater volcano off the coast of Sicily was named Empedocles.[72]

In 2016, Scottish musician Momus wrote and sang the song "The Death of Empedokles" for his album Scobberlotchers.[73]

See also

Notes

- "Empedokles did not die in Sicily, but in the Peloponnese, or, perhaps, at Thourioi."[2]

Citations

- Wright, M. R. (1981). Empedocles: The Extant Fragments. Yale University Press. p. 6.

- Burnet 1930, pp. 202–203.

- Burnet 1930, pp. 228.

- Burnet 1930, pp. 231-232.

- Burnet 1930, p. 232.

- Burnet 1930, pp. 208.

- Burnet 1930, p. 198.

- Zeller, Eduard (1881). A History of Greek Philosophy from the Earliest Period to the Time of Socrates. II. Translated by Alleyne, S. F. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 117–118.

- Burnet 1930, p. 197.

- Freeman, Kathleen (1946). The Pre-Socratic Philosophers. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. pp. 172–173.

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 51

- Burnet 1930, p. 199.

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 73

- Timaeus, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 64, comp. 65, 66

- Aristotle ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 63; compare, however, Timaeus, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, 66, 76

- Satyrus, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 78; Timaeus, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, 67

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 60, 70, 69; Plutarch, de Curios. Princ., adv. Colotes; Pliny, H. N. xxxvi. 27, and others

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 60, 61, 65, 69

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 60: "Pausanias, according to Aristippus and Satyrus, was his eromenos"

- Pliny, Natural History, xxix.1.4–5; cf. Suda, Akron

- Suda, Empedocles; Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 55, 56, etc.

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 58

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 71, 67; Athenaeus, xiv.

- Suda, Akron; Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 52

- Pliny, H. N. xxx. 1, etc.

- Apollonius, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 52, comp. 74, 73

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 67, 69, 70, 71; Horace, ad Pison. 464, etc. Refer to Arnold (1852), Empedocles on Etna.

- Inwood, Brad (2001). The poem of Empedocles : a text and translation with an introduction (rev. ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 8–21. ISBN 0-8020-8353-6.

- Osborne, Catherine (1987). Rethinking early Greek philosophy : Hippolytus of Rome and the Presocratics. London: Duckworth. pp. 24–31, 108. ISBN 0-7156-1975-6.

- Simon Trépanier, (2004), Empedocles: An Interpretation, Routledge.

- Hermippus and Theophrastus, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 55, 56

- Wallace, William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 344–345.

- Aristotle, Poetics, 1, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 57.

- See especially Lucretius, i. 716, etc. Refer to Sedley (1998).

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 77

- DK frag. B112 (Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 61)

- Frag. B115 (Plutarch, On Exile, 607 C–E; Hippolytus, vii. 29)

- Suda, Empedocles

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 60

- Aristotle, Metaphysics, i. 3, 4, 7, Phys. i. 4, de General, et Corr. i. 8, de Caelo, iii. 7.

- House, Humphry (1956). Aristotles Poetics. Rupert Hart-Davis. p. 32.

- James Luchte, Early Greek Thought: Before the Dawn, Bloomsbury, 2011.

- Frag. B17 (Simplicius, Physics, 157–159)

- Frag. B6 (Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians, x, 315)

- Peter Kingsley, in Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition (Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Plato, Timaeus, 48b–c

- Frank Reynolds, David Tracy (eds.), Myth and Philosophy, SUNY Press, 1990, p. 99.

- Frag. B35, B26 (Simplicius, Physics, 31–34)

- Frag. B35 (Simplicius, Physics, 31–34; On the Heavens, 528–530)

- Frag. B57 (Simplicius, On the Heavens, 586)

- Frag. B61 (Aelian, On Animals, xvi 29)

- Ted Everson (2007), The gene: a historical perspective page 5. Greenwood

- Let There be Light 7 August 2006 01:50 BBC Four

- Frag. B109 (Aristotle, On the Soul, 404b11–15)

- Frag. B100 (Aristotle, On Respiration, 473b1–474a6)

- Frag. B84 (Aristotle, On the Senses and their Objects, 437b23–438a5)

- Frag. B2 (Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians, vii. 123–125)

- Jonathan Barnes (2002), The Presocratic Philosophers, Routledge, p. 313.

- Carl Sagan (1980), Cosmos, Random House, pp. 179–80.

- Aristotle, Physics, 213a24–7

- W. K. C. Guthrie, (1980), A history of Greek philosophy II: The Presocratic tradition from Parmenides to Democritus, Cambridge University Press, p. 224.

- Frag. B127 (Aelian, On Animals, xii. 7); Frag. B117 (Hippolytus, i. 3.2)

- Heath, John (12 May 2005). The Talking Greeks: Speech, Animals, and the Other in Homer, Aeschylus, and Plato. Cambridge University Press. p. 322. ISBN 9781139443913.

An excellent study of Empedocles' vegetarianism and the various meanings of sacrifice in its cultural context is that of Rundin (1998).

- Plato (1961) [c. 360 BC]. Bluck, Richard Stanley Harold (ed.). Meno. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521172288.

This suggests that e.g. Empedocles' vegetarianism was partly at least due to the idea that the spilling of blood brings pollution.

- Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians, ix. 127; Hippolytus, vii. 21

- Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, iv. 23.150

- Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, v. 14.122

- Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 69

- Horace, Ars Poetica, 465–466

- Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy, 1946, p. 60

- JR by William Gaddis, Dalkey Archive, 2012

- BBC News, Underwater volcano found by Italy, 23 June 2006

- Freeman, Zachary (September 2016). "Albums". Now Then. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

References

- Arnold, Matthew (1852). Empedocles on Etna, and Other Poems. London: B. Fellows.

- Burnet, John (1930) [1892]. Early Greek Philosophy. London: A. & C. Black, Ltd. ark:/13960/t8bg7z77p.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.  Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.- Sedley, David (1998). Lucretius and the Transformation of Greek Wisdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Bakalis, Nikolaos (2005). Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics. Victoria, B.C.: Trafford. ISBN 1-4120-4843-5.

- Burnet, John (2003) [1892]. Early Greek Philosophy. Whitefish, Mont.: Kessinger. ISBN 0-7661-2826-1.

- Gottlieb, Anthony (2000). The Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9143-7.

- Guthrie, W. K. C. (1978) [1965]. A History of Greek Philosophy, vol. 2 (ed.). The Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29421-5.

- Hoffman, Eric (2018). Presence of Life. Loveland, Ohio: Dos Madres Press. ISBN 978-1-948017-16-9.

- Inwood, Brad (2001). The Poem of Empedocles (rev. ed.). Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-4820-X.

- Kingsley, Peter (1995). Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-814988-3.

- Kirk, G. S.; Raven, J.E.; Schofield, M. (1983). The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25444-2.

- Lambridis, Helle (1976). Empedocles : a philosophical investigation. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-6615-6.

- Long, A. A. (1999). The Cambridge Companion to Early Greek Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44122-6.

- Luchte, James (2011). Early Greek Thought: Before the Dawn. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0567353313.

- Millerd, Clara Elizabeth (1908). On the interpretation of Empedocles. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- O'Brien, D. (1969). Empedocles' cosmic cycle: a reconstruction from the fragments and secondary sources. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05855-4.

- Russell, Bertrand (1945). A History of Western Philosophy, and Its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-415-07854-7.

- Wright, M. R. (1995). Empedocles: The Extant Fragments (new ed.). London: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 1-85399-482-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Empedocles. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Empedocles |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Empedocles |

| Library resources about Empedocles |

| By Empedocles |

|---|

- Parry, Richard. "Empedocles". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Campbell, Gordon. "Empedocles". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Empedokles: Fragments, translated by Arthur Fairbanks, 1898.

- Empedocles by Jean-Claude Picot with an extended and updated bibliography

- Empedocles: Fragments at demonax.info

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Empedocles", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Works by or about Empedocles at Internet Archive

- Works by Empedocles at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)