Rangitoto Island

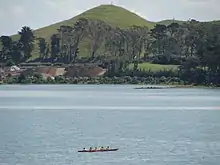

Rangitoto Island is a volcanic island in the Hauraki Gulf near Auckland, New Zealand. The 5.5 km (3.4 mi) wide island is a symmetrical shield volcano cone, reaching a height of 260 m (850 ft).[1][2] Rangitoto is the youngest and largest of the approximately 50 volcanoes of the Auckland volcanic field, having formed in an eruption about 600 years ago, and covering an area of 2,311 ha (5,710 acres).[2][3] It is separated from the mainland of Auckland's North Shore by the Rangitoto Channel. Since World War II, it has been linked by a causeway to the much older, non-volcanic Motutapu Island.[4]

| Ngā Rangi-i-totongia-a Tama-te-kapua (Māori) | |

|---|---|

Rangitoto Island viewed from the southwest | |

Rangitoto Island | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Auckland |

| Coordinates | 36.786742°S 174.860115°E |

| Highest point | 260 m (850 ft) |

| Administration | |

New Zealand | |

Rangitoto is Māori for 'Bloody Sky',[5] with the name coming from the full phrase Ngā Rangi-i-totongia-a Tama-te-kapua ("The days of the bleeding of Tama-te-kapua"). Tama-te-kapua was the captain of the Arawa waka (canoe) and was badly wounded on the island, after having lost a battle with the Tainui iwi (tribe) at Islington Bay.[3][6]

Geology

Rangitoto was formed during a single phase of eruptions that may have lasted only 5–10 years, about 600 years ago. Previous inferences that it was formed by a series of eruptions commencing at least 6000 years ago[7] have been disproved by the most recent research.[8] The first part of the eruption was wet and produced surges of volcanic ash that mantles neighbouring Motutapu Island. The later part of the eruption was dry and built most of Rangitoto, erupting all the lava flows and scoria cones at the apex.[9] The 2.3 km3 (0.55 cu mi) of material that erupted from the volcano was about equal to the combined mass produced by all the previous eruptions in the Auckland volcanic field, which were spread over more than 200,000 years.[6][10]

In 2013, scientists from Auckland University said new studies showed Rangitoto had been much more active in the past than previously thought, suggesting it had been active on and off for around 1000 years before the final eruptions around 550 years ago (BP= before 1950).[11] In February 2014 a 150 m (490 ft) deep hole was drilled through the western flank of Rangitoto. The same group of university scientists declared that it revealed a long history of spasmodic eruptions going back at least 6000 years, although the bulk of activity post-dated 650 years. Civil Defence officials said the discovery did not make living in Auckland any more dangerous, but did change their view of how an eruption might proceed.[12] These headline-grabbing results have been controversial and not accepted by all geologists.[13][14] In 2018, most of the original group of Auckland University geologists reported on their latest research and reinterpretation of the drillhole sequence[8] and pronounced that the island did not erupt off and on prior to its major eruption about 600 years ago and is not a unique polygenetic volcano in the monogenetic Auckland volcanic field, as they had previously inferred.[15] While it is possible that Rangitoto buried one or more smaller volcanoes, to date there is no strong evidence to support this idea.[16][17]

Subsidence back down the throat during the cooling process has left a moat-like ring around the crater summit, which may be viewed from a path which goes right round the rim and up to the highest point.[3][6] In some parts of the island, fields of clinker-like black lava stones are exposed, appearing very recent to a casual eye. About 200 metres from the top of the mountain on the eastern side visitors can walk through some of about seven known lava tubes — tubes left behind after the passage of liquid lava. The more accessible of the caves are signposted.[6] Lava tubes are formed when low-viscosity molten lava known as pahoehoe flows and cools on the outside due to contact with the ground and air, to form a hard crust allowing the still-liquid molten lava to continue to flow through inside. At Rangitoto the large tubes are cave-like. A torch is needed to explore the caves. The longest known cave is about 50 m long.[18]

Biology

Because there are virtually no streams on the island, plants rely on rainfall for moisture. It has the largest forest of pohutukawa trees in the world,[3] as well as many northern rata trees. In total, more than 200 species of trees and flowers thrive on the island, including several species of orchid, as well as more than 40 types of fern.[6] The vegetation pattern was influenced by the more recent eruptions creating lava flow crevices where pohutukawa trees (Metrosideros ssp) grow.[19]

The island is considered especially significant because all stages from raw lava fields to scrub establishment and sparse forests are visible. As lava fields contain no soil of the typical kind, windblown matter and slow breaking-down processes of the native flora are still in the process of transforming the island into a more habitable area for most plants (an example of primary succession), which is one of the reasons why the local forests are relatively young and do not yet support a large bird population. However, the kaka, a New Zealand-endemic parrot, is thought to have lived on the island in pre-European times.[6]

Goats were present on Rangitoto in large numbers in the mid 19th century and survived until the 1880s.[20] Fallow deer were introduced to Motutapu in 1862 and spread to Rangitoto, but disappeared by the 1980s. The brush-tailed rock-wallaby was introduced to Motutapu in 1873, and was common on Rangitoto by 1912, and the brushtail possum was introduced in 1931 and again in 1946. Both were eradicated in a campaign from 1990 to 1996 using 1080 and cyanide poison and dogs. The eradication campaign did not have a significant effect on bird species diversity and abundance, due to the presence of other predators.[21]

Stoats, rabbits, mice, rats, cats and hedgehogs remained a problem on the island,[20][22] but the Department of Conservation (DOC) aimed to eradicate them beginning with the poisoning of black rats, brown rats and mice and in August 2011, both Rangitoto and neighbouring Motutapu Islands were officially declared pest-free with both islands now also boasting populations of newly translocated North Island saddlebacks.[23]

As the area is a DOC-administered reserve (in partnership with the tangata whenua Ngāi Tai and Ngāti Paoa),[5] visitors may not take dogs or other animals onto the islands.[24]

History

Māori association

The volcano erupted within the historical memory of the local Māori iwi (tribes).[6][10] Human footprints have been found between layers of Rangitoto volcanic ash on the adjoining Motutapu Island.[10] Ngāi Tai was the iwi living on Motutapu, and considers both islands their ancestral home. Ngāti Paoa also has links with Rangitoto.[25]

A number of Māori myths exist surrounding the island, including that of a 'tupua' couple, children of the Fire Gods. After quarreling and cursing Mahuika, the fire-goddess, they lost their home on the mainland because it was destroyed by Mataoho, god of earthquakes and eruptions, on Mahuika's behalf. Lake Pupuke on the North Shore was created in the destruction, while Rangitoto rose from the sea. The mists surrounding Rangitoto at certain times are called the tears of the tupua for their former home.[6]

Since European colonisation

The island was purchased for £15 by the Crown in 1854, very early in New Zealand's colonisation by Europeans, and for many years served as a source of basalt for the local construction industry.[26] It was set aside as a recreation reserve in 1890, and became a favourite spot for daytrippers.[26] Some development occurred nonetheless. In 1892, salt works were created on 5 acres (20,000 m2) near Mackenzies Bay. The wharf and summit road were opened in 1897, with another road linking the summit to Islington Bay by 1900.[27] For over 30 years (from 1898 to 1930), scoria was quarried from near the shoreline on the west side of Islington Bay[28] as building material for Auckland.[29]

.jpg.webp)

From 1925 to 1936, prison labour built roads on the island and a track to the summit.[3] Islington Bay was formed in the southeast area of the island. Formerly known as Drunks Bay, it was used as a drying out area for inebriated crews before they ventured out of the gulf.[30] The bay is used by Auckland boat-owners as a refuge, as it is quite sheltered from the prevailing southwest winds.

Military installations were built during World War II to support the Auckland harbour defences and to house U.S. troops or store mines. The most visited remains of these installations is the old observation post on the summit. The northern shore of the island was used as a wrecking ground for unwanted ships, and the remains of several wrecks are still visible at low tide.[31][32] At least 13 ships were wrecked from 1887,[33] the last being the former Wellington[34] and, later, Waiheke ferry, Duchess,[35] in June 1947.[36]

Baches (small holiday houses) were built around the island's edge in the 1920s and 1930s. The legality of their existence was doubtful from the start and the building of further baches was banned in 1937. Most have since been removed because of the ban and because the island has become a scenic reserve. However, 30 of the 140 baches remain as of 2010,[26] and some are being preserved to show how the island used to be, once boasting a permanent community of several hundred people, including many children. The buildings included some more permanent structures like a seawater pool built of quarried stones by convict labour, located close to the current ferry quay.[37]

Access and tourism

Regular ferry services and island tours by tractor-trailer are provided by Fullers from Auckland city centre.[38] A boardwalk with around 300 steps allows visitors to reach the summit and enjoy a view of the wooded crater. The distance to the summit is 2.4 km (1.5 mi), a one–hour walk by the most direct route.[39]

An alternative to walking, a land train, coordinated with the ferry sailings, takes visitors to a short way below the summit.[24] Sea kayak trips from the mainland to the island are also available.[40]

There are no campsites on the island, though there is camping at Home Bay on the adjacent Motutapu Island.[41]

See also

- Auckland volcanic field

- Volcanism in New Zealand

- List of volcanoes in New Zealand

- Under the Mountain was a novel, TV series and film set around Rangitoto.

References

- "Auckland Field – Photo Gallery". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- "Auckland Field". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- Hauraki Gulf Islands – Rangitoto Island Archived 25 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Auckland City Council. Updated September 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- Ottaway, Jacqueline Crompton (30 April 2004). "Rangitoto – Auckland's Fragile Icon". NZine. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- What happened to local Maori? Archived 5 October 2003 at the Wayback Machine (from the Rangitoto page on the GNS Science website)

- Rangitoto Archived 20 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine (from the Auckland Regional Council website)

- Shane, Phil; Linnell, Tamzin (March 2015). "Reconstructing Rangitoto volcano from a 150-m-deep drill core (project 14/U684)" (PDF). University of Auckland. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Cronin,S., Kanakiya, S., Brenna, M., Shane, P., Smith, I., Ukstins, I., Horkley, K. (2018) Rangitoto Volcano, Auckland City. A one-shot wonder or a continued volcanic threat? url= http://www.devora.org.nz/download/1453/%7C

- Hayward, B.W.; Murdoch, G., Maitland, G. (2011). Volcanoes of Auckland: The Essential Guide. Auckland University Press.

- Rangitoto (abridged article from New Zealand National Geographic)

- "Rangitoto more active than thought – study". 3 News NZ. 11 April 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- "Officials downplay volcano danger". 3 News NZ. 12 April 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- Hayward, B.W.; Grenfell, H.R. 2013. Did Rangitoto erupt many times? Geoscience Society of New Zealand Newsletter 11: 5–8. url= https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258374103_Did_Rangitoto_erupt_many_times

- Hayward, B.W. 2017. Eruption sequence of Rangitoto Volcano, Auckland. Geoscience Society of New Zealand Newsletter 23: 4–10. url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321062566_Eruption_sequence_of_Rangitoto_Volcano_Auckland%7C

- McGee, L.; Beier, C.; Smith, I. E.; Turner, S. (2009). "Polygenetic magmatism in a monogenetic field: an isotopic investigation from the Auckland volcanic field, New Zealand". American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting. 24: V24C–02. Bibcode:2009AGUFM.V24C..02M.

- Morton, Jamie (28 March 2016). "Volcano hiding explosive secret". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- Linnell, Tamzin; et al. (2016). "Long-lived shield volcanism within a monogenetic basaltic field: The conundrum of Rangitoto volcano, New Zealand". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 128 (7–8): 1160–1172. Bibcode:2016GSAB..128.1160L. doi:10.1130/B31392.1.

- Auckland University, Geology Dept, field guide

- The vegetation pattern of Rangitoto (Thesis). University of Auckland. 1992. hdl:2292/27.

- Nichol, R (September 1992). "The eruption history of Rangitoto: reappraisal of a small New Zealand myth". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 22 (3): 170. doi:10.1080/03036758.1992.10426554. ISSN 0303-6758. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Spurr, Eric B.; Anderson, Sandra H. (2004). "Bird species diversity and abundance before and after eradication of possums and wallabies on Rangitoto Island, Hauraki Gulf, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 28 (1): 143–149. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Mike D Wilcox; et al. (2007). Natural History of Rangitoto Island. Auckland Botanical Society. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-0-9583447-3-9.

- Rangitoto & Motutapu restoration project, Department of Conservation.

- Rangitoto Island – Unique Volcanic Island (from the Fullers ferry operator website)

- Mike D Wilcox; et al. (2007). Natural History of Rangitoto Island. Auckland Botanical Society. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-9583447-3-9.

- "The Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, Part 2". Inset to The New Zealand Herald. 2 March 2010.

- Gordon Ell (1980). Rangitoto. Bush Jacket Guides. Auckland: The Bush Press. ISBN 978-0-908608-04-1.

- Wolfe, R. (2002). Auckland: a pictorial history. Auckland: Random House. p 228.

- Glenys Robertson (2005). Exploring North Island Volcanoes. Auckland: New Holland Publishers. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-86966-078-9.

- Gray, Matthew (23 March 2010). "Drunks Bay proves a fateful spot". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Rangitoto Ships' Graveyard". Auckland Regional Council website. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- Bennett, Kurt. "Rich Pickings: Abandoned Vessel Material Reuse on Rangitoto Island, New Zealand". Flinders University website. Retrieved 6 February 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Shipwrecks on Rangitoto". www.rangitoto.org. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- "New Zealand Maritime Index". www.nzmaritimeindex.org.nz. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- "Waiheke residents come to town NEW ZEALAND HERALD". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. 9 January 1932. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- "1931 – Duchess – Discover – STQRY". discover.stqry.com. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- Welcome to Rangitoto Island (from the Rangitoto Island Historic Conservation Trust)

- "Rangitoto Island". Fullers Group. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- McCormack, Michael (January 2019). "Active and Well in Nature with a Green Prescription: Rangitoto Island, NZ" (PDF). Activity and Nutrition Aotearoa.

- Kayak Trips to Rangitoto Archived 10 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Day Trips to Rangitoto Island)

- "Home Bay, Motutapu Island Campsite". www.doc.govt.nz. Department of Conservation. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Further reading

- Jamieson, Alastair (2004). "Rangitoto". New Zealand Geographic. 68. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016.

- Julian, Andrea (1992). The vegetation pattern of Rangitoto. University of Auckland PhD thesis

- Whiting, Diana (1986). Vegetation colonisation of Rangitoto Island: the role of crevice microclimate. University of Auckland Masters thesis

- Bennett, Kurt (2014). Rich pickings: Abandoned vessel material reuse on Rangitoto Island, New Zealand (PDF). Flinders University.

- Volcanoes of Auckland: A Field Guide. Hayward, B.W.; Auckland University Press, 2019, 335 pp. ISBN 0-582-71784-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rangitoto Island. |

- Rangitoto Island Scenic Reserve at the Department of Conservation

- Rangitoto Island Historic Conservation Trust

- Photographs of Rangitoto Island held in Auckland Libraries' heritage collections.

.jpg.webp)