Regiomontanus

Johannes Müller von Königsberg (6 June 1436 – 6 July 1476[1]), better known as Regiomontanus (/ˌriːdʒioʊmɒnˈteɪnəs/), was a mathematician, astrologer and astronomer of the German Renaissance, active in Vienna, Buda and Nuremberg. His contributions were instrumental in the development of Copernican heliocentrism in the decades following his death.

Regiomontanus | |

|---|---|

18th-century portrait (Iohannes de Regio Monte dictus alias Müllerus) | |

| Born | 6 June 1436 Unfinden near Königsberg in Bayern, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 6 July 1476 (aged 40) Rome, Papal States |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | University of Leipzig (no degree) University of Vienna (B.A., 1452; M.A., 1457) |

| Known for | Founding the world's first scientific printing press Publishing the first printed astronomical textbook (1472) and the first trigonometric tables (posthum., 1490) Tangent tables |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics (trigonometry), astronomy, astrology |

| Institutions | Universitas Istropolitana |

| Academic advisors | Georg von Peuerbach Basilios Bessarion |

| Notable students | Domenico Novara da Ferrara |

Regiomontanus wrote under the Latinized name of Ioannes de Monteregio (or Monte Regio; Regio Monte); the adjectival Regiomontanus was first used by Philipp Melanchthon in 1534. He is named after Königsberg in Lower Franconia, not the larger Königsberg (modern Kaliningrad) in Prussia.

Life

Although little is known of Regiomontanus' early life, it is believed that at eleven years of age, he became a student at the University of Leipzig, Saxony. In 1451 he continued his studies at Alma Mater Rudolfina, the university in Vienna, Austria. There he became a pupil and friend of Georg von Peuerbach. In 1452 he was awarded his bachelor's degree (baccalaureus), and he was awarded his master's degree (magister artium) at the age of 21 in 1457.[2] It is known that he held lectures in optics and ancient literature.[3]

In 1460 the papal legate Basilios Bessarion came to Vienna on a diplomatic mission. Being a humanist scholar and great fan of the mathematical sciences, Bessarion sought out Peuerbach's company. George of Trebizond who was Bessarion's philosophical rival had recently produced a new Latin translation of Ptolemy's Almagest from the Greek, which Bessarion, correctly, regarded as inaccurate and badly translated, so he asked Peuerbach to produce a new one. Peuerbach's Greek was not good enough to do a translation but he knew the Almagest intimately so instead he started work on a modernised, improved abridgement of the work. Bessarion also invited Peuerbach to become part of his household and to accompany him back to Italy when his work in Vienna was finished. Peuerbach accepted the invitation on the condition that Regiomontanus could also accompany them. However Peuerbach fell ill in 1461 and died only having completed the first six books of his abridgement of the Almagest. On his death bed Peuerbach made Regiomontanus promise to finish the book and publish it.[1][3]

In 1461 Regiomontanus left Vienna with Bessarion and spent the next four years travelling around Northern Italy as a member of Bessarion's household, looking for and copying mathematical and astronomical manuscripts for Bessarion, who possessed the largest private library in Europe at the time. Regiomontanus also made the acquaintance of the leading Italian mathematicians of the age such as Giovanni Bianchini and Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli who had also been friends of Peuerbach during his prolonged stay in Italy more than twenty years earlier.[1]

In 1467, he went to work for János Vitéz, archbishop of Esztergom. There he calculated extensive astronomical tables and built astronomical instruments.[2] Next he went to Buda, and the court of Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, for whom he built an astrolabe, and where he collated Greek manuscripts for a handsome salary.[4] The trigonometric tables that he created while living in Hungary, his Tabulae directionum profectionumque (printed posthum., 1490), were designed for astrology, including finding astrological houses.[5] The Tabulae also contained several tangent tables.[6]

In 1471 Regiomontanus moved to the Free City of Nuremberg, in Franconia, then one of the Empire's important seats of learning, publication, commerce and art, where he worked with the humanist and merchant Bernhard Walther.[4] Here he founded the world's first scientific printing press, and in 1472 he published the first printed astronomical textbook, the Theoricae novae Planetarum of his teacher Georg von Peurbach.[1]

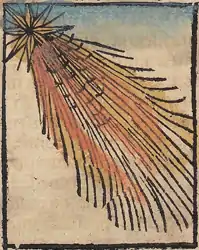

Regiomontanus and Bernhard Walther observed the comet of 1472. Regiomontanus tried to estimate its distance from Earth, using the angle of parallax.[lower-alpha 1] According to David A. Seargeant:[7]

In agreement with the prevailing Aristotelian theory on comets as atmospheric phenomena, he estimated its distance to be at least 8,200 miles (13,120 km) and, from this, estimated the central condensation as 26, and the entire coma as 81 miles (41.6 and 129.6 km respectively) in diameter. These values, of course, fail by orders of magnitude, but he is to be commended for this attempt at determining the physical dimensions of the comet.

The 1472 comet was visible from Christmas Day 1471 to 1 March 1472 (Julian Calendar), a total of 59 days.[8]

In 1475, Regiomontanus was called to Rome by Pope Sixtus IV on to work on the planned calendar reform. Sixtus promised substantial rewards, including the title of bishop of Regensburg,[9][10] it is unlikely that he was actually appointed to the role.[3]

On his way to Rome, stopping in Venice, he commissioned the publication of his Calendarium with Erhard Ratdolt (printed in 1476).[11] Regiomontanus reached Rome, but he died there after only a few months, in his 41st year, on 6 July 1476. According to a rumor repeated by Gassendi in his Regiomontanus biography, he was poisoned by relatives of George of Trebizond whom he had criticized in his writing; it is however considered more likely that he died from the plague.[1]

Work

During his time in Italy he completed Peuerbach's Almagest abridgement, Epytoma in almagesti Ptolemei. In 1464, he completed De triangulis omnimodis ("On Triangles of All Kinds"). De triangulis omnimodis was one of the first textbooks presenting the current state of trigonometry and included lists of questions for review of individual chapters. In it he wrote:

You who wish to study great and wonderful things, who wonder about the movement of the stars, must read these theorems about triangles. Knowing these ideas will open the door to all of astronomy and to certain geometric problems.

His work on arithmetic and algebra, Algorithmus Demonstratus, was among the first containing symbolic algebra.[12] In 1465, he built a portable sundial for Pope Paul II.

In Epytoma in almagesti Ptolemei, he critiqued the translation of Almagest by George of Trebizond, pointing out inaccuracies. Later Nicolaus Copernicus would refer to this book as an influence on his own work.

A prolific author, Regiomontanus was internationally famous in his lifetime. Despite having completed only a quarter of what he had intended to write, he left a substantial body of work. Nicolaus Copernicus' teacher, Domenico Maria Novara da Ferrara, referred to Regiomontanus as having been his own teacher. There is speculation that Regiomontanus had arrived at a theory of heliocentrism before he died; a manuscript shows particular attention to the heliocentric theory of the Pythagorean Aristarchus, mention was also given to the motion of the earth in a letter to a friend.[13]

Much of the material on spherical trigonometry in Regiomontanus' On Triangles was taken directly from the twelfth-century work of Jabir ibn Aflah otherwise known as Geber, as noted in the sixteenth century by Gerolamo Cardano.[14]

Legacy

Simon Stevin, in his book describing decimal representation of fractions (De Thiende), cites the trigonometric tables of Regiomontanus as suggestive of positional notation.[15]

Regiomontanus designed his own astrological house system, which became one of the most popular systems in Europe.[16]

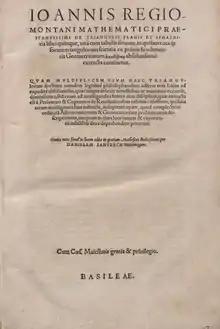

In 1561, Daniel Santbech compiled a collected edition of the works of Regiomontanus, De triangulis planis et sphaericis libri quinque (first published in 1533) and Compositio tabularum sinum recto, as well as Santbech's own Problematum astronomicorum et geometricorum sectiones septem. It was published in Basel by Henrich Petri and Petrus Perna.

There is an image of him in Hartmann Schedel's 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle. He is holding an astrolabe.[lower-alpha 2] Yet, although there are thirteen illustrations of comets in the 'Chronicle (from 471 to 1472), they are stylized, rather than representing the actual objects.[lower-alpha 3]

The crater Regiomontanus on the Moon is named after him.

Notes

- See NASA: parallax.

- See image.

- See image.

References

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Regiomontanus", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Folkerts, Menso; Kühne, Andreas (2003), "Regiomontan(us) (eigentlich Müller, auch Francus, Germanus), Johannes", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 21, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 270–271CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); (full text online)

-

Hagen, Johann Georg (1911). "Johann Müller (Regiomontanus)". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Hagen, Johann Georg (1911). "Johann Müller (Regiomontanus)". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Clerke, Agnes Mary (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Mosley, Adam (1999). "Regiomontanus and Astrology". Cambridge University: History and Philosophy of Science Department. Retrieved 2013-06-12.

- Denis Roegel, "A reconstruction of the tables of Rheticus' Canon doctrinæ triangulorum (1551)", 2010.

- David A. Seargeant. The Greatest Comets in History, 2009, p. 104

- Donald K. Yeomans, Jet Propulsion Laboratory: Great Comets in History, 2007.

- Boffut, Carl (1804). Versuch einer allgemeinen Geschichte der Mathematik (in German). L. G. Hoffmann. p. 351.

- Rudolf Schmidt, Regiomontanus, Johann in: Deutsche Buchhändler. Deutsche Buchdrucker vol. 5 (1908), 797f.

- "Erhard Ratdolt". Open Book. University of Utah. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Arthur Koestler, The Sleepwalkers, Penguin Books, 1959, p. 212.

- Victor J. Katz, ed. (2007). The mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: a sourcebook. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9., p.4

- E. J. Dijksterhuis (1970) Simon Stevin: Science in the Netherlands around 1600, pages 17–19, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Dutch original 1943

- Lewis, James R. (1 March 2003). The Astrology Book: The Encyclopedia of Heavenly Influences. Visible Ink Press. p. 574. ISBN 978-1-57859-144-2. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

Further reading

- Irmela Bues, Johannes Regiomontanus (1436–1476). In: Fränkische Lebensbilder 11. Neustadt/Aisch 1984, pp. 28–43

- Rudolf Mett: Regiomontanus. Wegbereiter des neuen Weltbildes. Teubner / Vieweg, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1996, ISBN 3-8154-2510-7

- Helmuth Gericke: Mathematik im Abendland: Von den römischen Feldmessern bis zu Descartes. Springer-Verlag, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-540-51206-3

- Günther Harmann (Hrsg.): Regiomontanus-Studien. (= Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-historische Klasse, Sitzungsberichte, Bd. 364; Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für Geschichte der Mathematik, Naturwissenschaften und Medizin, volumes 28–30), Vienna 1980. ISBN 3-7001-0339-5

- Samuel Eliot Morison, Christopher Columbus, Mariner, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1955.

- Ralf Kern: Wissenschaftliche Instrumente in ihrer Zeit/Band 1. Vom Astrolab zum mathematischen Besteck. Köln, 2010. ISBN 978-3-86560-865-9

- Ernst Zinner: Leben und Wirken des Joh. Müller von Königsberg, genannt Regiomontanus; Translated into English by Ezra A. Brown as Regiomontanus: His Life and Work

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Johannes Regiomontanus. |

- "Regiomontanus". Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German).

- Günther (1885), "Johannes Müller Regiomontanus", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German), 22, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 564–581

- Adam Mosley, Regiomontanus Biography, web site at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science of the University of Cambridge (1999).

- Electronic facsimile-editions of the rare book collection at the Vienna Institute of Astronomy

- Regiomontanus and Calendar Reform

- Polybiblio: Regiomontanus, Johannes/Santbech, Daniel, ed. De triangulis planis et sphaericis libri. Basel Henrich Petri & Petrus Perna 1561

- Joannes Regiomontanus: Calendarium, Venedig 1485, Digitalisat

- Beitrag bei „Astronomie in Nürnberg“

- Digitalisierte Werke von Regiomontanus — SICD der Universitäten von Strasbourg

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (9th ed.). 1886.

- Regiomontanus at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Regiomontanus in .jpg and .tiff format.

- Regiomontanus, Joannes, 1436-1476. Calendarium. Venice, Bernhard Maler Pictor, Erhard Ratdolt, Peter Löslein, 1476. [32] leaves. woodcuts: border, diagrs. (1 movable, 1 with brass pointer) 29.6 cm. (4to). From the Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Doctissimi viri et mathematicarum disciplinarum eximii professoris Ioannis de Regio Monte De triangvlis omnímodis libri qvinqve From the Rare Book and Special Collection Division at the Library of Congress

- Regiomontanus' Defensio Theonis digital edition (scans and transcription)

.jpg.webp)