Relations between Nazi Germany and the Arab world

The relationship between Nazi Germany (1933–1945) and the leadership of the Arab world encompassed contempt, propaganda, collaboration, and in some instances emulation.[2][3][4] Cooperative political and military relationships were founded on shared hostilities toward common enemies, such as the United Kingdom[3][4] and the French Third Republic,[2][3] along with communism, and Zionism.[2][3][4] Another key foundation of this collaboration was the anti-Semitism of the Nazis and their hostility towards the United Kingdom and France, which was admired by some Arab and Muslim leaders, most notably the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini[3] (see Anti-Semitism in Islam). In public and private, Adolf Hitler and Heinrich Himmler made warm statements about Islam as a religion and political ideology, describing it as a more disciplined, militaristic, political, and practical form of religion than Christianity, and commending what they perceived to be Muhammad's skill in politics and military leadership. However, the official Nazi racial ideology also considered Arabs and North Africans to be racially inferior to Germans, a sentiment echoed by Hitler and other Nazi leaders to deprecate them.[2] Hitler left no doubt about his disdain for the Arab world, writing in Mein Kampf: "As a völkisch man, who appraises the value of men on a racial basis, I am prevented by mere knowledge of the racial inferiority of these so-called 'oppressed nations' from linking the destiny of my own people with theirs".[5]

The Arabic-speaking world has attracted particular attention from historians examining Fascism beyond Europe. Focusing exclusively on pro-Nazi and pro-Fascist forces, these scholars have tended to emphasize the appeal that Fascism and Nazism had across the Arab world. More recently however, this narrative has been challenged by a number of scholars[6] who assert that Arab political debates in the 1930s and 1940s were quite complex. Fascism and Nazism, they argue, were discussed alongside other political ideologies, such as communism, liberalism, and constitutionalism. Moreover, the recent revisionist works have stressed the anti-Fascist and anti-Nazi voices and movements in the Arab world.[7][8] Despite the Mufti's efforts to get German backing for Arab independence, Hitler refused, remarking that he "wanted nothing from the Arabs".[9]

Nazi perceptions of the Arab world

In speeches, Hitler purportedly made apparently warm references towards Muslim culture such as: "The peoples of Islam will always be closer to us than, for example, France".[10] Hitler was transcribed as saying: "Had Charles Martel not been victorious at Poitiers [...] then we should in all probability have been converted to Mohammedanism, that cult which glorifies the heroism and which opens up the seventh Heaven to the bold warrior alone. Then the Germanic races would have conquered the world."[11]

This exchange occurred when Hitler received Saudi Arabian ruler Ibn Saud's special envoy, Khalid al-Hud al-Gargani.[12] Earlier in this meeting, Hitler noted that one of the three reasons why Nazi Germany had some interest in the Arabs was:

[...] because we were jointly fighting the Jews. This led him to discuss Palestine and the conditions there, and he then stated that he himself would not rest until the last Jew had left Germany. Kalid al Hud observed that the Prophet Mohammed [...] had acted the same way. He had driven the Jews out of Arabia [...][13]

Gilbert Achcar wrote that the Führer "did not find it useful" to point out to his Arab visitors at that meeting that until then he had incited German Jews to emigrate to Palestine (see Aliyah Bet and Timeline of the Holocaust), and the Third Reich actively helped Zionist organizations get around British-imposed restrictions on Jewish immigration.[14]

Hitler had told his military commanders in 1939, shortly before the beginning of World War II: "We shall continue to make disturbances in the Far East and in Arabia. Let us think as men and let us see in these peoples at best lacquered half-apes who are anxious to experience the lash."[15][16]

Prior to the Second World War, all of North Africa and the Middle East were under the rule of European colonial powers. Despite the Nazi racial theory which denigrated Arabs as members of an inferior race, individual Arabs who assisted the Third Reich in fighting against the Allies were treated with dignity and respect. The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini, for example, "was granted honorary Aryan" status by the Nazis for his close collaboration with Hitler and the Third Reich.[17]

The Nazi government developed a cordial association and cooperated with some Arab nationalist leaders based on their common enemies and shared distaste towards Jews and Zionism. The most notable examples of these common-cause fights were the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine and other actions led by Amin al-Husseini, and the Anglo-Iraqi War, when the Golden Square (four generals led by Rashid Ali al-Gaylani) overthrew the pro-British 'Abd al-Ilah regency in Iraq and installed a pro-Axis government.[18][19][20]

In response to the Rashid Ali coup, Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 30 on 23 May 1941, to support their cause. This order began: "The Arab Freedom Movement in the Middle East is our natural ally against England."[20]

On 11 June 1941, Hitler and the supreme commander of the armed forces issued Directive No. 32:

Exploitation of the Arab Freedom Movement. The situation of the English in the Middle East will be rendered more precarious, in the event of major German operations, if more British forces are tied down at the right moment by civil commotion or revolt. All military, political, and propaganda measures to this end must be closely coordinated during the preparatory period. As central agency abroad I nominate Special Staff F, which is to take part in all plans and actions in the Arab area, whose headquarters are to be in the area of the Commander Armed Forces South-east. The most competent available experts and agents will be made available to it. The Chief of the High Command of the Armed Forces will specify the duties of Special Staff F, in agreement with the Foreign Minister where political questions are involved.[21]

Arab perceptions of Hitler and Nazism

According to Gilbert Achcar, there was no unified Arab perception of Nazism:

In the first place, there is no such thing as Arabs. To speak in the singular of an Arab discourse is an aberration. The Arab world is driven by a multiplicity of points of view. At the time, one could single out four major ideological currents, which extend from western liberalism, through Marxism and nationalism, to Islamic fundamentalism. In regard to these four, two, namely western liberalism and Marxism, clearly rejected Nazism, in part on shared grounds (such as the heritage of enlightenment thinkers, and the denunciation of Nazism as a form of racism), and partially because of their geopolitical affiliations. On this issue, Arab nationalism is contradictory. If one looks into it closely, however, the number of nationalistic groups which identified themselves with Nazi propaganda turns out to be quite scaled-down. There is only one clone of Nazism in the Arab world, namely the Syrian social national party, which was founded by a Lebanese Christian, Antoun Saadeh. The Young Egypt Party flirted for a time with Nazism, but it was a fickle, weathercock party. As to accusations that the Ba'ath party was, from the very outset in the 1940s, inspired by Nazism, they are completely false.[22]

Hitler and fascist ideology were controversial in the Arab world, just as they were in Europe, with both supporters and opponents.

Massive programs of propaganda were launched in the Arab world, first by Fascist Italy and later on by Nazi Germany. The Nazis in particular focused on impacting the new generation of political thinkers and activists.[23]

Erwin Rommel was almost as popular as Hitler. "Heil Rommel" was reportedly a common greeting in Arab countries. Some believed the Germans would help them in gaining independence from French and British rule. After France's defeat by Nazi Germany in 1940, some Arabs were making public chants against the French and British in the streets of Damascus: "No more Monsieur, no more Mister, Allah's in Heaven and Hitler's on earth."[24] Posters in Arabic stating "In heaven God is your ruler, on earth Hitler" were frequently displayed in shops in the towns of Syria.[25]

Some wealthy Arabs who traveled to Germany in the 1930s brought back fascist ideals and incorporated them into Arab nationalism. One of the principal founders of Ba'athist thought and the Ba'ath Party, Zaki al-Arsuzi, stated that Fascism and Nazism had greatly influenced Ba'athist ideology. A student of al-Arsuzi, Sami al-Jundi, wrote:

We were racialists, admiring Nazism, reading its books and the source of its thought, particularly Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Fichte's Addresses to the German Nation, and H. S. Chamberlain's The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, which revolves on race.[26] We were the first to think of translating Mein Kampf.

Whoever has lived during this period in Damascus will appreciate the inclination of the Arab people to Nazism, for Nazism was the power which could serve as its champion, and he who is defeated will by nature love the victor. But our belief was rather different.[27]

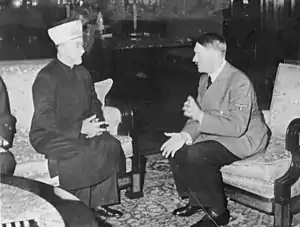

The two most noted Arab politicians who actively collaborated with the Nazis were the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini,[28][29] and the Iraqi prime minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani.[30][31]

The British sent Amin al-Husseini into exile for his role in the Palestinian revolt of 1936–39. The ex-Mufti had agents in the Kingdom of Iraq, the French Mandate of Syria and in Mandatory Palestine. In 1941, al-Husseini actively supported the Iraqi Golden Square coup d'état, led by Rashid Ali al-Gaylani.[32]

After the Golden Square Iraqi regime was defeated by British forces, Rashid Ali, al-Husseini and other Iraqi veterans took refuge in Europe, where they supported Axis interests. They were particularly successful in recruiting several tens-of-thousands of Muslims for membership in German Schutzstaffel (SS) units, and as propagandists for the Arabic-speaking world. The range of collaborative activities was wide. For instance, Anwar Sadat, who later became president of Egypt, was a willing co-operator in Nazi Germany's espionage according to his own memoirs.[23] Adolf Hitler met with Amin al-Husseini on 28 November 1941. The official German notes of that meeting contain numerous references to combatting Jews both inside and outside Europe. The following excerpts from that meeting are statements from Hitler to al-Husseini:

Germany stood for uncompromising war against the Jews. That naturally included active opposition to the Jewish national home in Palestine, which was nothing other than a center, in the form of a state, for the exercise of destructive influence by Jewish interests. ... This was the decisive struggle; on the political plane, it presented itself in the main as a conflict between Germany and England, but ideologically it was a battle between National Socialism and the Jews. It went without saying that Germany would furnish positive and practical aid to the Arabs involved in the same struggle, because platonic promises were useless in a war for survival or destruction in which the Jews were able to mobilize all of England's power for their ends....the Fuhrer would on his own give the Arab world the assurance that its hour of liberation had arrived. Germany's objective would then be solely the destruction of the Jewish element residing in the Arab sphere under the protection of British power. In that hour the Mufti would be the most authoritative spokesman for the Arab world. It would then be his task to set off the Arab operations, which he had secretly prepared. When that time had come, Germany could also be indifferent to French reaction to such a declaration.[33][34][35]

Amin al-Husseini became the most prominent Arab collaborator with the Axis powers. He developed friendships with high-ranking Nazis, including Heinrich Himmler, Joachim von Ribbentrop, and (possibly) Adolf Eichmann. He contributed to Axis propaganda services and to the recruitment of Muslim and Arab soldiers for the Nazi armed forces, including three SS divisions consisting of Bosnian Muslims.[36] He was involved in planning "wartime operations directed against Palestine and Iraq, including parachuting Germans and Arab agents to foment attacks against the Jews in Palestine."[37] He assisted the German entry into North Africa, particularly the German entry into Tunisia and Libya. His espionage network provided the Wehrmacht with a forty-eight-hour warning of the Allied invasion of North Africa. The Wehrmacht, however, ignored this information, which turned out to be completely accurate. He intervened and protested to government authorities in order to prevent Jews from emigrating to Mandatory Palestine.[38] There is persuasive evidence that he was aware of the Nazi Final Solution.[39] After the war ended, he claimed that he never knew about the extermination camps or Nazi plans for the genocide of European Jews, that the evidence against him was forged by his Jewish enemies, and even denied having met Eichmann. He is still a controversial figure, both vilified and honored by different political factions in the contemporary Arab world.[40]

Researchers like Jeffrey Herf, Meir Zamir, and Hans Goldenbaum agree on the importance of the German propaganda effort in the Middle East and North Africa. But latest research on the massive and influential radio broadcasts was able to prove "that the texts were supplied by German personnel and not, as sometimes believed, by the reader[s] of the Arabic broadcasts [...]". Furthermore, Goldenbaum concludes "that the man who was long regarded as the Reich's most important Muslim of all, Mohammed Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, did not play any particularly important role in this case. Despite the fact that his Arabic speeches were broadcast by Radio Berlin and he was always presented as a role model, al-Husseini did not have any influence on the broadcast content. The Arabs in general did not seem to have been partners with equal rights. Instead they were secondary recipients of propaganda and orders, Goldenbaum concluded. Cooperation never went beyond the emphasized common battle against colonialism."[41][42]

Opposition

Gilbert Achcar, a professor of Development Studies at the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies, argues that historical narratives often over-emphasize collaboration and under-appreciate progressive Arab political history, overshadowing the many dimensions of conflict between Nazism and the Arab World. He accuses Zionists of promulgating a 'collaborationist' narrative for partisan purposes. He proposes that the dominant Arab political attitudes were 'anti-colonialism' and 'anti-Zionism,' though only a comparatively small faction adopted anti-Semitism, and most Arabs were actually pro-Ally and anti-Axis (as evidenced by the high number of Arabs who fought for Allied forces). Achcar states:

The Zionist narrative of the Arab world is based centrally around one figure who is ubiquitous in this whole issue—the Jerusalem Grand Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husseini, who collaborated with the Nazis. But the historical record is actually quite diverse. The initial reaction to Nazism and Hitler in the Arab world and especially from the intellectual elite was very critical towards Nazism, which was perceived as a totalitarian, racist and imperialist phenomenon. It was criticized by the liberals or what I call the liberal Westernizers, i.e. those who were attracted by Western liberalism, as well as by the Marxists and left-wing nationalists who denounced Nazism as another form of imperialism. In fact, only one of the major ideological currents in the Arab world developed a strong affinity with Western anti-Semitism, and that was Islamic fundamentalism—not all Islam or Islamic movements but those with the most reactionary interpretations of Islam. They reacted to what was happening in Palestine by espousing Western anti-Semitic attitudes.[43]

Cooperation

Muslim Brotherhood formation

According to Steven Carol, the Brotherhood was heavily financed by Nazi Germany, which contributed greatly to its growth.[44] According to Carol, in 1939 al-Bannah received twice as much funds from Germany per month, as the entire yearly Muslim Brothers' fundraising for the Palestinian cause.[44]

Mandatory Palestine

The Palestinian Arab and Nazi political leaders said that they had a common cause against "International Jewry". However, the most significant practical effect of Nazi anti-Jewish policy between 1933 and 1942 was to radically increase the immigration rate of German and other European Jews to Palestine and to double the population of Palestinian Jews. Al-Husseini had sent messages to Berlin through Heinrich Wolff, the German consul general in Jerusalem, endorsing the advent of the Nazi regime as early as March 1933, and was enthusiastic over the Nazi anti-Jewish policy, and particularly the anti-Jewish boycott in Nazi Germany. "[The Mufti and other sheikhs asked] only that German Jews not be sent to Palestine."[45]

Nazi policy for solving their Jewish problem until the end of 1937 emphasized motivating German Jews to emigrate from German territory. During this period the League of Nations Mandate for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Mandatory Palestine to be used as a refuge for Jews was "still internationally recognized". The Gestapo and the SS inconsistently cooperated with a variety of Jewish organizations and efforts (e.g., Hanotaiah Ltd., the Anglo-Palestine Bank, the Temple Society Bank, HIAS, Joint Distribution Committee, Revisionist Zionists, and others), most notably in the Haavurah Agreements, to facilitate emigration to Mandatory Palestine.[46]

Nora Levin wrote in 1968: "Up to the middle of 1938, Palestine had received one third of all the Jews who had emigrated from Germany since 1933 – 50,000 out of a total of 150,000."[47] Edwin Black, benefitting from more modern scholarship, has written that 60,000 German Jews immigrated into Palestine between 1933 through 1936, bringing with them $100,000,000 dollars ($1.6 billion in 2009 dollars). This precipitous increase in the Jewish Palestinian population stimulated Palestinian Arab political resistance to continued Jewish immigration, and was a principal cause for the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, which in turn led to the British White Paper decision to abandon the League of Nations Mandate to establish a Jewish national home in Palestine. The resultant change in British policy effectively closed Palestine to most European Jews who were fleeing Nazi persecution during World War II. After 1938 the majority of Zionist organizations adhered to a strategy of "Fighting the White Paper as if there was not War, and fighting the War as if there was no White Paper". Zionists would smuggle Jews in Palestine whenever possible, regardless if this brought them into conflict with the British authorities. At the same time, the Zionists and other Jews would ally themselves to the British struggle against Germany and the Axis powers, even while the British authorities refused to allow the migration of European Jews into Palestine.[48]

In 1938, the German policy toward the Jewish homeland in Palestine appears to have substantially changed, as indicated in this German Ministry of Foreign Affairs note from 10 March 1938:

The influx into Palestine of German capital in Jewish hands will facilitate the building up of a Jewish state, which runs counter to German interests; for this state, instead of absorbing world Jewry, will someday bring about a considerable increase in world Jewry's political power.[49]

One consequence of al-Husseini's opposition to Britain's mandate in Palestine and his rejection of the British attempts to work out a compromise between Zionists and Palestinian Arabs was that the Mufti was exiled from Palestine. Many of his followers, who had fought in guerilla campaigns against Jews and the British in Palestine, followed him and continued to work for his political goals. Among the most notable Palestinian soldiers in this category was Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni, a kinsman and officer of al-Husseini who had been wounded twice in the early stages of the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. Al-Husseini sent Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni to Germany in 1938 for explosives training. Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni then worked with al-Husseini to support the Golden Square regime, and consequently was tried and sent to prison by the British after they recaptured Iraq. He subsequently became the popular leader of approximately 50,000 Palestinian Arabs who joined the Mufti's Army of the Holy War during the 1947-1948 Arab–Israeli War. His fellow Iraq-veteran and German collaborator Fawzi al-Qawuqji became a rival general in that same struggle against Zionism.[50]

After the Kristallnacht pogroms in November 1938, most Jewish and Zionist organizations aligned with Britain and its allies to oppose Nazi Germany. After this time the organized assistance by the Gestapo to the Jewish organizations who transported European Jews to Palestine became much more sporadic, although bribery of individual Germans often help accomplish such operations even after official policy discouraged them.[51]

Al-Husseini opposed all immigration of Jews into Palestine. His numerous letters appealing to various governmental authorities to prevent Jewish emigration to Palestine have been widely republished and cited as documentary evidence of his collaboration with the Nazis and his participative support for their actions. For instance, in June 1943, al-Husseini recommended to the Hungarian minister that it would be better to send the Jewish population of Hungary to the Nazi concentration camps in Poland rather than let them find asylum in Palestine (it is not entirely clear whether al-Husseini was aware of the extermination camps in Poland, e.g. Auschwitz, at this time):

I ask your Excellency to permit me to draw your attention to the necessity of preventing the Jews from leaving your country for Palestine, and if there are reasons which make their removal necessary, it would be indispensable and infinitely preferable to send them to other countries where they would find themselves under active control, for example, in Poland ...[52]

Achcar quotes al-Husseini's memoirs about these efforts to influence the Axis powers to prevent emigration of Eastern European Jews to Palestine:

We combatted this enterprise by writing to Ribbentrop, Himmler, and Hitler, and, thereafter, the governments of Italy, Hungary, Rumania, Bulgaria, Turkey, and other countries. We succeeded in foiling this initiative, a circumstance that led the Jews to make terrible accusations against me, in which they held me accountable for the liquidation of four hundred thousand Jews who were unable to emigrate to Palestine in this period. They added that I should be tried as a war criminal in Nuremberg.[53]

Achcar then notes that although al-Husseini's motivation to block Jewish emigration into Palestine:

was certainly legitimate when it was addressed as an appeal to the British mandatory authorities ... It had no legitimacy whatsoever when addressed to Nazi authorities who had cooperated with the Zionists to send tens of thousands of German Jews to Palestine and then set out to exterminate the Jews of Europe. The Mufti was well aware that the European Jews were being wiped out; he never claimed the contrary. Nor, unlike some of his present-day admirers, did he play the ignoble, perverse, and stupid game of Holocaust denial ... His armour-propre would not allow him to justify himself to the Jews ... gloating that the Jews had paid a much higher price than the Germans ... he cites : "Their losses in the Second World War represent more than thirty percent of the total number of their people ... Statements like this, from a man who was well placed to know what the Nazis had done ... constitute a powerful argument against Holocaust deniers. Husseini reports that Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler ... told him in summer 1943 that the Germans had 'already exterminated more than three million' Jews: "I was astonished by this figure, as I had known nothing about the matter until then." ... Thus. in 1943, Husseini knew about the genocide ... Himmler ... again in the summer of 1941 ... let him in on a secret that ... Germany would have an atomic bomb in three years' time ...[54]

In November 1943, when he became aware of the nature of the Nazi Final Solution, al-Husseini said:

It is the duty of Muhammadans in general and Arabs in particular to drive all Jews from Arab and Muhammadan countries ... Germany is also struggling against the common foe who oppressed Arabs and Muhammadans in their different countries. It has very clearly recognized the Jews for what they are and resolved to find a definitive solution [endgültige Lösung] for the Jewish danger that will eliminate the scourge that Jews represent in the world.[55]

Kingdom of Iraq

On 1 April 1941, a day after General Erwin Rommel began his Tunisian offensive, the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état overthrew the pro-British Kingdom of Iraq. Fritz Grobba served intermittently as the German ambassador in Iraq from 1932 to 1941, supporting anti-Jewish and fascist movements in the Arab world. Intellectuals and army officers were invited to Germany as guests of the Nazi party, and antisemitic material was published in the newspapers. The German embassy purchased the newspaper al-Alam al-Arabi ("The Arab World") which published antisemitic, anti-British, and pro-Nazi propaganda, including a serialized translation of Hitler's Mein Kampf in Arabic.[56]

While Nazi Germany was not openly allied with the Ba'athist government in Iraq like Fascist Italy was during the Anglo-Iraqi War,[57] it provided air support. On 1–2 June 1941, immediately after the collapse of the pro-Fascist Rashid Ali government in Iraq, al-Husseini and others inspired a pogrom against the Jewish population of Baghdad known as "the Farhud". The estimates of Jewish victims vary from less than 110 to over 600 killed, and from 240 to 2000 wounded. Gilbert Achcar claims that historian Bernard Lewis cites the numbers (officially 600 killed and 240 injured, with unofficial sources being "much higher") as the number of Jewish victims, without citing a single reference.[58] Edwin Black concludes that the exact numbers will never be known, pointing out the improbability of the initial estimate in the official reports of 110 fatalities that included both Arabs and Jews (including 28 women), as opposed to the claims of Jewish sources that as many as 600 Jews were killed.[59] Similarly, the estimates of Jewish homes destroyed range from 99 to over 900 houses. Though these figures are debated in the secondary literature, it is generally agreed that over 580 Jewish businesses were looted. The Iraqi-Arab Futuwwa youth group—modeled after the Hitler Youth—were widely credited with the Farhud. The Futuwwa were commanded by Iraqi minister of education Saib Shawkat, who also praised Hitler for eradicating Jews.[60][61][62]

In June 1941, Wehrmacht High Command Directive No. 32 and the "Instructions for Special Staff F" designated Special Staff F as the Wehrmacht's central agency for all issues that affected the Arab world.[63]

North Africa

On 20 January 1942, 15 high-ranking Nazi Party and German government officials met at a villa in Wannsee, a Berlin suburb, to coordinate the execution of the "Final Solution" (Endlösung) of the Jewish Question. At this Wannsee Conference, Reinhard Heydrich, Heinrich Himmler's deputy and head of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Main Office, or RSHA), noted the numbers of Jews to be eliminated in each territory. In the notation for France there are two entries, 165,000 for Occupied France, and 700,000 for the Unoccupied Zone, which included France's North African possessions, i.e. Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.[64][65][66]

The SS had established a special unit of 22 people in 1942 "to Kill Jews in North Africa". It was led by the SS functionary Walter Rauff, who helped develop the mobile gassing vehicles the Germans used to murder Russian prisoners and Jewish people in Russia and Poland. A network of labor camps was established in Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco.[67] Over 2,500 Tunisian Jews perished during a six-month period in these camps.[68]

According to Robert Satloff, only one Arab in North Africa, Hassan Ferjani, was convicted by an Allied military tribunal in World War II for performing actions that led to the deaths of Jews, male members of the Scemla family of Tunisia, while many Arabs acted to save Jews.[69] For instance, King Mohammed V refused to make the 200,000 Jews who were living in Morocco wear yellow stars, even though this discriminatory practice was enforced in France. He is reported to have said: "There are no Jews in Morocco. There are only subjects."[70] The historian Haim Saadon opines that bar some exceptions, there was no violence towards Jews from Muslims and that although there was no particular sense of camaraderie, Jews and Muslims treated each other quite well.[71]

Arab exiles in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy

Following the defeat of the Golden Square in Iraq in May–June 1941, Rashid Ali al-Gaylani fled to Iran but was not to stay long. On 25 August 1941, Anglo-Soviet forces invaded Iran, removing Reza Shah from power. Gaylani then fled to German-occupied Europe. In Berlin, he was received by German dictator Adolf Hitler, and he was recognized as the leader of the Iraqi government in exile. Upon the defeat of Germany, Gaylani again fled and found refuge, this time in Saudi Arabia.

Amin al-Husseini arrived in Rome on 10 October 1941. He outlined his proposals before Alberto Ponce de Leon. On condition that the Axis powers "recognize in principle the unity, independence, and sovereignty, of an Arab state, including Iraq, Syria, Palestine, and Transjordan", he offered support in the war against Britain and stated his willingness to discuss the issues of "the Holy Places, Lebanon, the Suez Canal, and Aqaba". The Italian foreign ministry approved al-Husseini's proposal, recommended giving him a grant of one million lire, and referred him to Benito Mussolini, who met al-Husseini on 27 October. According to al-Husseini's account, it was an amicable meeting in which Mussolini expressed his hostility to the Jews and Zionism.[72]

Back in the summer of 1940 and again in February 1941, al-Husseini submitted to the Nazi German Government a draft declaration of German-Arab cooperation, containing a clause:

Germany and Italy recognize the right of the Arab countries to solve the question of the Jewish elements, which exist in Palestine and in the other Arab countries, as required by the national and ethnic (völkisch) interests of the Arabs, and as the Jewish question was solved in Germany and Italy.[73]

Al-Husseini helped organize Arab students and North African emigres in Germany into the Free Arabian Legion in the German Army that hunted down Allied parachutists in the Balkans and fought on the Russian front.[74]

Arab incorporation and emulation of Nazism

Several emerging movements in the Arab world were influenced by European fascist and Nazi organizations during the 1930s. The Young Egypt Party ("Green shirts") closely resembled the Hitler Youth and was "obviously Nazi in form", according to historian Bernard Lewis.[75] The fascist[76] pan-Arabist Al-Muthanna Club and its al-Futuwwa (Hitler Youth) type[77] movement, participated in the 1941 Farhud attack on Baghdad's Jewish community.[78][79]

The Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) adopted styles of fascism. Its emblem, the red hurricane, was taken from the Nazi swastika,[80] leader Antoun Saadeh was known as al-za'im (the leader), and the party anthem was "Syria, Syria, über alles" sung to the same tune as the German national anthem.[81] He founded the fascist SSNP with a program that Syrians were "a distinctive and naturally superior race".[82]

See also

- Arab rescue efforts during the Holocaust

- Collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II

- Contemporary imprints of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

- History of antisemitism

- Khairallah Talfah

- Mein Kampf in Arabic

- Muhammad Najati Sidqi

- Mediterranean and Middle East theatre of World War II

- New antisemitism

- Operation Atlas (Mandatory Palestine)

- Transport of Białystok children

References

- Fisk, Robert (2007) [2005]. The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East. London: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-307-42871-4. OCLC 84904295.

- Herf, Jeffrey (December 2009). "Nazi Germany's Propaganda Aimed at Arabs and Muslims During World War II and the Holocaust: Old Themes, New Archival Findings". Central European History. Cambridge University Press. 42 (4): 709–736. doi:10.1017/S000893890999104X. JSTOR 40600977. S2CID 145568807.

- • "Hajj Amin al-Husayni: Wartime Propagandist". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Washington, D.C.: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2020. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

• "Hajj Amin al-Husayni: Arab Nationalist and Muslim Leader". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Washington, D.C.: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2020. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2020. - Spoerl, Joseph S. (January 2020). "Parallels between Nazi and Islamist Anti-Semitism". Jewish Political Studies Review. Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. 31 (1/2): 210–244. ISSN 0792-335X. JSTOR 26870795. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- Herf, Jeffrey (2010). Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-30-016805-1.

- Among them are the works by Peter Wien (2006) and Orit Bashkin (2009) on Iraq, Rene Wildangel (2007) on Palestine, Götz Nordbruch (2009) on Lebanon and Syria, and Israel Gershoni and James Jankowski (2010) on Egypt.

- Motadel, David (3 March 2016). "Arab Responses to Fascism and Nazism: Attraction and Repulsion, edited by Israel Gershoni". Middle Eastern Studies. 52 (2): 377–379. doi:10.1080/00263206.2015.1121872. S2CID 147486609.

- Wien, Peter (2016). Arab Nationalism: The Politics of History and Culture in the Modern Middle East. London: Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-315-41219-1. OCLC 975005824.

Until recently, European and Anglo-American research on these topics – often based on a history of ideas approach – tended to take for granted the natural affinity of Arabs towards Nazism. More recent works have contextualized authoritarian and totalitarian trends in the Arab world within a broad political spectrum, choosing subaltern perspectives and privileging the analysis of local voices in the press over colonial archives and the voices of grand theoreticians.

- "Hajj Amin al-Husayni: Wartime Propagandist". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Hitler's apocalypse: Jews and the Nazi legacy, Robert S. Wistrich, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 17 Oct 1985, page 59

- Cameron et al. 2007, p. 667.

- The Arabs and the Holocaust: The Arab-Israeli War of Narratives, by Gilbert Achcar, (NY: Henry Holt and Co.; 2009), pp. 125—126.

- "Arabs & Holocaust, Achcar", pp. 125—126.

- "Arabs & Holocaust, Achcar" p. 125.

- Stefan Wild (1985). "National Socialism in the Arab near East between 1933 and 1939". Die Welt des Islams. New Series. 25 (1/4): 126–173. doi:10.2307/1571079. JSTOR 1571079.

Wir werden weiterhin die Unruhe in Fernost und in Arabien schüren. Denken wir als Herren und sehen in diesen Völkern bestenfalls lackierte Halbaffen, die die Knute spüren wollen.

- Wolfgang Schwanitz (2008). "The Bellicose Birth of Euro-Islam in Berlin". In Ala Al-Hamarneh and Jörn Thielmann (ed.). Islam and Muslims in Germany. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. p. 203. ISBN 978-9004158665.

- David G, Dalin John F. Rothmann (2009). Icon of Evil: Hitler's Mufti and the Rise of Radical Islam. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-1077-7.

- Nafi, Basheer M. "The Arabs and the Axis: 1933-1940". Arab Studies Quarterly, Vol. 19, Issue 2, Spring 1997

- Nazi Palestine: The Plans for the Extermination of the Jews in Palestine by Klaus-Michael Mallmann and Martin Cuppers, tran. by Krista Smith, (Enigma Books, published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, NY; 2010)

- Churchill, Winston (1950). The Second World War, Volume III, The Grand Alliance. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, p.234; Kurowski, Franz (2005). The Brandenburger Commandos: Germany's Elite Warrior Spies in World War II. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Book. ISBN 978-0-8117-3250-5, 10: 0-8117-3250-9. p. 141

- "Blitzkrieg to Defeat: Hitler's War Directives, 1939–1945" edited with an Introduction and Commentary by H. R. Trevor-Roper (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1964), pp. 80–81.

- Christophe Ayad, Gilbert Achcar ‘Sait-on qu ‘un Palestinien a créé un musée de l’Holocaust?, at Libération 27 March 2010.'D'abord, les Arabes, ça n'existe pas. Parler d'un discours arabe au singulier est une aberration. Le monde arabe est traversé par une multitude de points de vue. A l'époque, on pouvait distinguer quatre grands courants idéologiques, qui vont de l'occidentalisme libéral à l'intégrisme islamique en passant par le marxisme et le nationalisme. Sur ces quatre courants, deux rejetaient clairement le nazisme : l'occidentalisme libéral et le marxisme, en partie pour des raisons communes (l'héritage des lumières, la dénonciation du nazisme comme racisme), et en partie à cause de leurs affiliations géopolitiques. Le nationalisme arabe est contradictoire sur cette question. Mais si on regarde de près, le nombre de groupes nationalistes qui se sont identifiés à la propagande nazie est finalement très réduit. Il y a un seul clone du nazisme dans le monde arabe, c'est le Parti social nationaliste syrien, fondé par un chrétien libanais, Antoun Saadé. Le mouvement égyptien Jeune Egypte a flirté un temps avec le nazisme, mais c'était un parti girouette. Quant aux accusations selon lesquelles le parti Baas était d'inspiration nazie à sa naissance dans les années 40, elles sont complètement fausses.

- Lewis, Bernard (1995). The Middle East: A Brief History of the last 2,000 Years. Simon & Schuster. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-684-80712-6.

- Friedmann, Jan (23 May 2007). "World War II: New Research Taints Image of Desert Fox Rommel". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- Stefan Wild (1985). "National Socialism in the Arab near East between 1933 and 1939". Die Welt des Islams. 25 (1/4): 128. JSTOR 1571079.

- According to Gilbert Achcar, The Arabs and the Holocaust (2010), p.69, "which revolves on race" is a mistranslation for "and Darré's The Race".

- Elie Kedourie (1974). Arabic Political Memoirs and Other Studies. London: Frank Cass. pp. 199–201.

- Mallmann, Klaus-Michael; Martin Cüppers (2010). Nazi Palestine: The Plans for the Extermination of the Jews in Palestine. Krista Smith (translator). Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1-929631-93-3.

- "The Mufti and the Führer". JVL. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- McKale, Donald M. (1987). Curt Prüfer, German diplomat from the Kaiser to Hitler. Kent State University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-87338-345-5.

- "The Farhud". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- Patterson, David (2010). A Genealogy of Evil: Anti-Semitism from Nazism to Islamic Jihad. Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-521-13261-9.

- Documents on German Foreign Policy 1918–1945, Series D, Vol XIII, London, 1964, p. 881

- Akten zur deutschen auswärtigen Politik, Series D, Vol. XIII, 2, No. 515

- Hitlers Weisungen für die Kriegführung 1939–1945, ed. by Walther Hubatsch (Frankfurt: Bernard und Graefe, 1962) pp. 129–39

- Mattar, Philip (1992). The Mufti of Jerusalem: Haj Amin al-Husseini and the Palestinian National Movement. Columbia University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-231-06463-7.

- Nazi War Crimes & Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group Final Report to the United States Congress April 2007, 1-880875-30-6, , p. 87

- Collins, Larry and Lapierre, Dominique (1972): O Jerusalem!, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-66241-4., pp. 49, 50

- Collins & Lapierre, pp. 49, 50 : "Fully aware of the Final Solution, he had done his best to see that none of the intended victims were diverted to Palestine on their way to Reichsfuhrer Heinrich Himmler's gas chambers."

- Achcar 2009, p. 154

- Delving Into Nazi Germany's Arabic Language Propaganda, Sven F. Kellerhoff, http://www.worldcrunch.com/culture-society/delving-into-nazi-germany-s-arabic-language-propaganda/c3s21516/

- Nationalsozialismus als Antikolonialismus. Die deutsche Rundfunkpropaganda für die arabische Welt, Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Volume 64, Issue 3, Pages 449–490

- The Holocaust Palestine and the Arab World: Gilbert Achcar interviewed 26 August 2014

- Carol, Steven (2015). Understanding the Volatile and Dangerous Middle East: A Comprehensive Analysis. p. 481. ISBN 9781491766583.

After ten years, the Ikhwan had only 800 members, but the Muslim Brotherhood became a regional force after receiving massive aid from Nazi Germany. [...] In 1939, they transferred to al-Bannah some E£1,000 per month, a substantial sum at the time. In comparison, the Muslim Brotherhood fundraising for the cause of Palestine yielded only E£500 for that entire year. This Nazi funding enabled the Muslim Brotherhood to expand internationally. By the end of World War II, it had a million members.

- "Arabs & Holocaust, Achcar" p. 135

- "The Mufti of Jerusalem and the Nazis: The Berlin Years" by Klaus Gensicke, translated by Alexander Fraser Gunn ( London & Portland, OR: Vallentine Mitchell ;2011); Original edition: "Der Mufti von Jerusalem" (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft; 2007), pp. 26—28

- The Holocaust: The Destruction of European Jewry 1933-1945, by Nora Levin, (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company; 1968) p. 130

- "The Transfer Agreement: The Dramatic Story of the Pact between the Third Reich and Jewish Palestine" by Edwin Black (New York: First Dialog; 2009)

- "The Holocaust" (1968), p. 131

- Collins and Lapierre, pp. 86–88

- "The Holocaust" (1968)

- "Arabs & Holocaust, Achcar" p. 148

- "Arabs & Holocaust, Achcar" pp. 145–146

- "Arabs & Holocaust, Achcar" pp. 146–147

- "Arabs & Holocaust, Achcar" pp. 151–152

- Podeh, et al, 2006, p. 135

- "Italy and Saudi Arabia confronting the challenges of the XXI century" p.20

- "Arabs & Holocaust, Achcar, pp. 100-101"

- Edwin Black (2010). The Farhud: Roots of the Arab-Nazi Alliance in the Holocaust. Washington, DC: Dialog Press. ISBN 978-0914153146, p. 186

- Rosen, Robert N. (2006). Saving the Jews: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Holocaust. p. 158. ISBN 9781560257783.

- Craig, Olga (27 April 2003). "You boys you are the seeds from which our great President Saddam will rise again". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- Lewis, Bernard. Semites and Anti-Semites. 1999, p. 158

- "German Exploitation of Arab Nationalist Movements in World War II" by Gen. Hellmuth Felmy and Gen, Walter Warlimont, Historical Division, Headquarters, United States Army, Europe, Foreign Military Studies Branch, 1952, p. 11, by Gen. Haider

- Atlas of the Holocaust, by Martin Gilbert (New York: William Morrow & Company; 1993)

- Gilbert, Martin (1985). The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. Henry Holt and Co. p. 281. ISBN 9780805003482.

- Longerich, Peter (15 April 2010). Holocaust. ISBN 9780192804365.

- Among the Righteous: Lost Stories from the Holocaust's Long Reach Into Arab Lands, by Robert B. Satloff (New York: Public Affairs; 2006), p.209

- Satloff, pp 57–72

- Satloff, p. 15

- "Moroccan Jews pay homage to 'protector'". Haaretz. Associated Press. 28 January 2005.

- SHEFLER, Gil Stern Stern (24 January 2011). "Jewish–Muslim Ties in Maghreb Were Good Despite Nazis". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Lewis 1999, pp. 150–151

- Lewis 2002, p. 190

- Medoff 1996, p. ?

- Lewis, Bernard (17 May 1999). Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry Into Conflict and Prejudice. ISBN 9780393318395.

- Bashkin, Orit (20 November 2008). The Other Iraq: Pluralism and Culture in Hashemite Iraq. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804774154.

- Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East & North Africa: D-K Por Philip Mattar, p. 860

- Memories of state: politics, history, and collective identity in modern Iraq by Eric Davis Eric Davis, University of California Press, 2005, P. 14

- http://www.fpri.org/orbis/4902/davis.historymattersiraq.pdf

- Rolland, John C. (2003). Lebanon: current issues and background. Nova Publishers. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-59033-871-1.

- Yapp, Malcolm (1996). The Near East since the First World War: a history to 1995. A history of the Near East. Longman Original (from the University of Michigan). p. 113. ISBN 978-0-582-25651-4.

- Pryce-Jones, David (2002). The closed circle: an interpretation of the Arabs G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Ivan R. Dee. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-56663-440-3.

Further reading

- Nazi Palestine: The Plans for the Extermination of the Jews in Palestine by Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Martin Cüppers, trans. by Krista Smith (Original German title: Halbmond und HakenKreuz: das Dritte Reich, die Araber und Palastina)

- Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World by Jeffrey Herf (Yale University Press, 2009) ISBN 978-0-300-14579-3.

- Nationalsozialismus als Antikolonialismus. Die deutsche Rundfunkpropaganda für die arabische Welt by Hans Goldenbaum, in ierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Volume 64, Issue 3, Pages 449–490.

- Germany and the Middle East, 1871-1945 edited by Wolfgang G. Schwanitz (Princeton, New Jersey: Markus Wiener Publishers; 2004) ISBN 1-55876-298-1

- The Arabs and the Holocaust: The Arab-Israeli War of Narratives, by Gilbert Achcar, (New York: Henry Holt and Co.; 2009)

- "The Farhud: Roots of the Arab-Nazi Alliance in the Holocaust" by Edwin Black, (Washington DC: Dialog Press; 2010) ISBN 978-0914153146

- "The Mufti of Jerusalem and the Nazis: The Berlin Years" by Klaus Gensicke, translated by Alexander Fraser Gunn ( London & Portland, Oregon:Vallentine Mitchell; 2011); Original edition: "Der Mufti von Jerusalem" (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft; 2007)

- "The Grand Mufti : Haj Amin al-Hussaini, Founder of the Palestinian National Movement" by Zvi Elpeleg ( London & Portland, Oregon: Frank Cass; 1993)

- "Nazism in Syria and Lebanon: The Ambivalence of the German Option" by Götz Nordbruch, 1933–1945 (London/New York: Routledge, 2008).

- "Fritz Grobba and the Middle East Policy of the Third Reich," by Francis Nicosia, in National and International Politics in the Middle East: Essays in Honour of Elie Kedourie, ed. Edward Ingram (London, 1986): 206-228.

- "Arab Nationalism and National Socialist Germany, 1933-1939: Ideological and Strategic Incompatibility", by Francis Nicosia, International Journal of Middle East Studies 12 (1980): 351-372.

- "National Socialism in the Arab Near East between 1933-1939", by Stefan Wild, Die Welt des Islams, New Series 25 nr 1 (1985): 126-173

- "The Third Reich and the Near and Middle East, 1933-1939", by Andreas Hillgruber, in The Great Powers in the Middle East, 1919-1939, ed. Uriel Dann (New York, 1988), 274-282.

External links

- Bruno de Cordier, The Fedayeen of the Reich: Muslims, Islam and Collaborationism During World War II in The China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly Vol 8, No 1, 2010.