March 1933 German federal election

Federal elections were held in Germany on 5 March 1933, after the Nazi seizure of power on 30 January and just six days after the Reichstag fire. Nazi stormtroopers had unleashed a widespread campaign of violence against the Communist Party (KPD), left-wingers,[1]:317 trade unionists, the Social Democratic Party of Germany,[1] and the Centre Party.[1]:322 They were the last multi-party elections in Germany until 1946.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

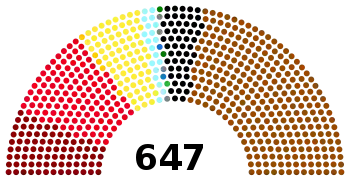

All 647 seats in the Reichstag 324 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered | 44,685,764 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 39,655,029 (88.74%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

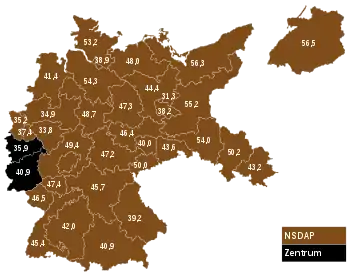

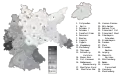

Electoral map | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1933 election followed the previous year's two elections (July and November) and Hitler's appointment as Chancellor. In the months before the 1933 election, brownshirts and SS displayed "terror, repression and propaganda [...] across the land",[1]:339 and Nazi organizations "monitored" the vote process. In Prussia 50,000 members of the SS, SA and Der Stahlhelm were ordered to monitor the votes by acting Interior Minister Hermann Göring, as auxiliary police.[2]

The National Socialists registered a large increase in votes in 1933. However, despite waging a campaign of terror against their opponents, the National Socialists only tallied 43.9 percent of the vote, well short of a majority. They needed the votes of their coalition partner, the German National People's Party (DNVP), for a bare working majority in the Reichstag.

This would be the last contested election held in Germany before World War II. Two weeks after the election, Hitler was able to pass an Enabling Act on 23 March with the support of all non-socialist parties, which effectively gave Hitler dictatorial powers. Within months, the Nazis banned all other parties and turned the Reichstag into a rubberstamp legislature comprising only Nazis and pro-Nazi guests.

Background

The Nazi seizure of power commenced on 30 January, when President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor, who immediately urged the dissolution of the Reichstag and the calling of new elections. In early February, the Nazis "unleashed a campaign of violence and terror that dwarfed anything seen so far".[3] Stormtroopers began attacking trade union and Communist Party (KPD) offices and the homes of left-wingers.[1]:317

In the second half of February, the violence was extended to the Social Democrats, with gangs of brownshirts breaking up Social Democrat meetings and beating up their speakers and audiences. Issues of Social Democratic newspapers were banned.[1]:318–320 Twenty newspapers of the Centre Party, a party of Catholic Germans, were banned in mid-February for criticising the new government. Government officials known to be Centre Party supporters were dismissed from their offices, and stormtroopers violently attacked party meetings in Westphalia.[1]:322 Only the Nazis and DNVP were allowed to campaign unmolested.

Six days before the scheduled election date, the German parliament building was set alight in the Reichstag fire, allegedly by the Dutch Communist Marinus van der Lubbe. That event reduced the popularity of the KPD and enabled Hitler to persuade Hindenburg to pass the Reichstag Fire Decree as an emergency decree according to Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution. The emergency law removed many civil liberties and allowed the arrest of Ernst Thälmann and 4,000 other leaders and members of the KPD[1]:331 shortly before the election, suppressing the Communist vote and consolidating the position of the Nazis.

Although Hitler could have banned the KPD outright, he opted not to do so. He feared a violent Communist uprising in the event of a ban, and he also believed the KPD's presence on the ballot could siphon off votes away the Social Democrats. Instead, he opted to simply have Communists functionaries jailed by the thousands. The courts and prosecutors, both already hostile to the KPD long before 1933, obligingly agreed with the line that since the Reichstag fire was a Communist plot, KPD membership was an act of treason. As a result, for all intents and purposes, the KPD was "outlawed" on the day the Reichstag Fire Decree took effect and "completely banned" as of the day of the election.[1]:335–336 While the Social Democrats (SPD) were then not as heavily oppressed as the Communists, the Social Democrats were also restricted in their actions, as the party's leadership had already fled to Prague, and many members were acting only from the underground. Hence, the Reichstag fire is widely believed to have had a major effect on the outcome of the election. As a replacement parliament building and for 10 years to come, the new parliament used the Kroll Opera House for its meetings.

The resources of big business and the state were thrown behind the Nazis' campaign to achieve saturation coverage all over Germany. Brownshirts and SS patrolled and marched menacingly through the streets of cities and towns. A "combination of terror, repression and propaganda was mobilized in every... community, large and small, across the land".[1]:339 Irene von Goetz wrote, "In a decree issued on 17 February 1933, Göring ordered the Prussian police force to make unrestrained use of firearms in operations against political opponents (the so-called Schießerlass, or shooting decree)".[2]

To ensure a Nazi majority in the vote, Nazi organisations also "monitored" the vote process. In Prussia, 50,000 members of the SS, SA and Der Stahlhelm were ordered to monitor the votes as so-called deputy sheriffs or auxiliary police (Hilfspolizei) in another decree by acting Interior Minister Hermann Göring.[2]

Results

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/– |

| National Socialist German Workers' Party | 17,277,180 | 43.91 | +10.82 | 288 | +92 |

| Social Democratic Party of Germany | 7,181,629 | 18.25 | -2.18 | 120 | –1 |

| Communist Party of Germany | 4,848,058 | 12.32 | -4.52 | 81 | –19 |

| Centre Party | 4,424,905 | 11.25 | -0.68 | 73 | +3 |

| German National People's Party (DNVP)[a] | 3,136,760 | 7.97 | -0.37 | 52 | +1 |

| Bavarian People's Party | 1,073,552 | 2.73 | -0.36 | 19 | –1 |

| German People's Party | 432,312 | 1.10 | -0.76 | 2 | –9 |

| Christian Social People's Service | 383,999 | 0.98 | -0.16 | 4 | –1 |

| German State Party | 334,242 | 0.85 | -0.10 | 5 | +3 |

| German Farmers' Party | 114,048 | 0.29 | -0.13 | 2 | –1 |

| Agricultural League | 83,839 | 0.21 | -0.09 | 1 | –1 |

| German-Hanoverian Party | 47,743 | 0.12 | -0.04 | 0 | –1 |

| Socialist Struggle Community | 3,954 | 0.01 | +0.01 | 0 | New |

| Workers' and Farmers' Struggle Community | 1,110 | 0.00 | - | 0 | 0 |

| Invalid/blank votes | 311,698 | – | – | – | - |

| Total | 39,655,029 | 100 | - | 647 | +63 |

| Registered voters/turnout | 44,685,764 | 88.74 | +8.16 | – | – |

| Source: Gonschior.de | |||||

a The Black-White-Red Struggle Front (KSWR) was an alliance of the German National People's Party with Der Stahlhelm and the Agricultural League

Nazi vote share, with majorities in E Prussia (1), Frankfurt (Oder) (5), Pomerania (6), Breslau (7), Liegnitz (8), Schleswig-Holstein (13), E Hanover (15), and Chemnitz-Zwickau (30)

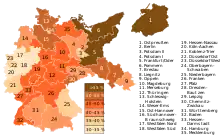

Nazi vote share, with majorities in E Prussia (1), Frankfurt (Oder) (5), Pomerania (6), Breslau (7), Liegnitz (8), Schleswig-Holstein (13), E Hanover (15), and Chemnitz-Zwickau (30) Social Democrat (SPD) vote share

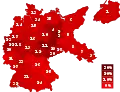

Social Democrat (SPD) vote share Communist Party (KPD) vote share

Communist Party (KPD) vote share Centre Party vote share – the largest party in Cologne-Aachen and Koblenz-Trier. In all 33 other districts, the Nazis were the largest party.

Centre Party vote share – the largest party in Cologne-Aachen and Koblenz-Trier. In all 33 other districts, the Nazis were the largest party.

Aftermath

Despite achieving a much better result than in the November 1932 election, the Nazis did not do as well as Hitler had hoped. In spite of massive violence and voter intimidation,[1][2] the Nazis won only 43.9% of the vote, rather than the majority that he had expected.

Therefore, Hitler was forced to maintain his coalition with the DNVP to control the majority of seats. The Communists (KPD) lost about a quarter of their votes, and the Social Democrats suffered only moderate losses. Although the KPD had not been formally banned, it was a foregone conclusion that the KPD deputies would never be allowed to take their seats. Within a few days, all KPD representatives had been placed under arrest or gone into hiding.

Although the Nazi-DNVP coalition had enough seats to conduct the basic business of government, Hitler needed a two-thirds majority to pass the Enabling Act, which allowed the Cabinet, effectively the Chancellor to enact laws without the approval of the Reichstag for four years. With certain exceptions, such laws could deviate from the Weimar Constitution. Leaving nothing to chance, the Nazis used the provisions of the Reichstag Fire Decree to arrest all 81 Communist deputies and to keep several Social Democrats out of the chamber.

Hitler then obtained the necessary supermajority by persuading the Centre Party to vote with him with regard to the Reichskonkordat. The bill was passed on 23 March with 444 votes for and 94 against. Only the Social Democrats, led by Otto Wels, opposed the measure, which came into effect on 27 March. As it turned out, the atmosphere of that session was so intimidating that the measure would have still passed even if all Communist and Social Democratic deputies had been present and voted against it. The bill's provisions turned the government into a de facto legal dictatorship.

Within four months, the other parties had been shuttered by outright banning or Nazi terror, and Germany had become formally a one-party state. Although three more elections were held during the Nazi era, voters were presented with a single list of Nazis and guest candidates, and voting was not secret.

References

- Evans, Richard J. (2004). The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 1-59420-004-1.

- von Götz, Irene. "Violence Unleashed". Berlin.de. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Coming of the Third Reich. Penguin. ISBN 9781101042670. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

External links

- 1933 elections German Historic Museum (in German)

.jpeg.webp)