Religion in Kerala

Kerala has a reputation of being, communally, one of the most religiously diverse states in India. According to 2011 Census of India figures, 54.73% of Kerala's population are Hindus, 26.56% are Muslims, 18.38% are Christians, and the remaining 0.33% follow other religions or have no religion.[2] Various tribal people in Kerala have retained the religious beliefs of their ancestors.[3][4]

Religion in Kerala (2011 Official Census)[1]

Hindus constitute the majority in all districts except Malappuram, where they are outnumbered by Muslims.[3] In 2018, 43.80% of the total reported births in the state were to Muslims, 41.61% to Hindus, 14.31% to Christians and 0.25% to others, according to the vital statistics published by the Government of Kerala.[4]

Hinduism

Several saints and movements existed. Adi Shankara was a Hindu philosopher who contributed to Hinduism and propagated philosophy of Advaita. He was instrumental in establishing four mathas at Sringeri, Dwarka, Puri and Jyotirmath. Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri was another Brahmin religious figure who composed Narayaniyam, a collection of verses in praise of Krishna.

Some of the most notable temples are:Thrissur Vadakkunnathan Temple, Guruvayur Temple, Thriprayar Temple, Sabarimala Ayyappa Temple, Thiruvananthapuram Padmanabhaswamy Temple, Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple, Chottanikkara Temple, Chengannur Mahadeva Temple, Parassinikadavu Muthappan Temple, Chettikulangara Devi Temple, Mannarasala Temple, Chakkulathukavu Temple, Thiruvalla Sreevallabha Temple, Kaviyoor Mahadevar Temple, Parumala Panayannarkavu Temple, Sree Poornathrayesa Temple, Kodungallur Bhagavathy Temple, Trikkur Mahadeva Temple, Manalarkavu Devi Temple and Rajarajeshwara Temple. Temples in Kerala follow elaborate rituals and traditionally only priests from the Nambudiri caste could be appointed as priests in major temples. But in 2017 as per the state government's decision, the priests from the historically backward caste communities are now being appointed as priests.

Malayali Hindus have unique ceremonies such as Chorunu (first feeding of rice to a child) and Vidyāraṃbhaṃ.[5]

Islam

- Islam is the second largest practised religion in Kerala (26.56%) next to Hinduism.[6] The calculated Muslim population (Indian Census, 2011) in Kerala state is 8,873,472.[7][8]

- Most of the Muslims in Kerala follow the Shāfiʿī School (Sunni Islam), followed by Salafi movement.[9]

- Muslims in Kerala share a common language (Malayalam) with the rest of the non-Muslim population and have a culture commonly regarded as the Malayali culture.[10]

- Very much unlike other parts of South Asia, the caste system does not exist among the Muslims of Kerala. A number of different communities, some of them having distant ethnic roots, exist as status groups in Kerala.[11]

History

Islam arrived in Kerala, a part of the larger Indian Ocean rim, via spice and silk traders from the Middle East. Historians do not rule out the possibility of Islam being introduced to Kerala as early as the seventh century CE.[12][13] Notable has been the occurrence of Cheraman Perumal Tajuddin, the Hindu King that moved to Arabia to meet the Islamic Prophet Muhammad and converted to Islam.[14][15][16] The Muslims were a major financial power to be reckoned with in the old kingdoms of Kerala and had great political influence in the Hindu royal courts.[17][18] Travellers have recorded the considerably huge presence of Muslim merchants and settlements of sojourning traders in most of the ports of Kerala.[19] Immigration, intermarriage and missionary activity/conversion — secured by the common interest in the spice trade — helped in this development.[20][21] Muslim merchant magnates owning ships, spread their shipping and trading business interests across the Indian Ocean.[22][23]

The arrival of the Portuguese traders in the late 15th century checked the then well-established and wealthy Muslim community's progress.[24] By the mid-18th century the majority of the Muslims of Kerala were landless labourers, poor fishermen and petty traders, and the community was in "a psychological retreat".[25] The subsequent partisan rule of English East India Company authorities brought the land-less Muslim peasants of Malabar District into a condition of destitution, and this led to a series of uprisings (against the Hindu landlords and British administration). The series of violence eventually exploded as the infamous Mappila Uprising (1921–22).[26][27]

A large number of Muslims of Kerala found extensive employment in the Persian Gulf countries in the following years (c. 1970s). This widespread participation in the "Gulf Rush" produced huge economic and social benefits for the community. Great influx funds from the earnings of the employed followed. Issues such as widespread poverty, unemployment and educational backwardness began to change.[28] The Muslims in Kerala are now considered as section of Indian Muslims marked by recovery, change and positive involvement in the modern world. Malayali Muslim women are now not reluctant to join professional vocations and assuming leadership roles.[29] As per the latest government data, female literacy rate in Malappuram District, center of Mappila distribution, stood at 91.55% (2011 Census).[30]

Politics

Politically, the Muslims in Kerala have exhibited more unanimity than any other major communities in modern Kerala.[31]

- Ever since the Indian Independence from the British in 1947, the overwhelming majority of Muslims in former Malabar District (Northern Kerala) have supported the Muslim League.[31]

- In south Kerala, the community generally supported the Indian National Congress and in northern Kerala a small proportion vote Communist.[31]

Judaism

Judaism arrived in Kerala with spice traders, possibly as early as the 7th century BC.[32] There is no consensus of opinion on the date of the arrival of the first Jews in India. The tradition of the Cochin Jews maintains that after 72 AD, after the destruction of the Second Temple of Jerusalem, 10,000 Jews migrated to Kerala.[32]

The only verifiable historical evidence about the Kerala Jews goes back only to the Jewish Copper Plate Grant of Bhaskara Ravi Varman in 1000 AD.[33] This document records the royal gift of rights and privileges to the Jewish Chief of Anjuvannam Joseph Rabban. Later in the 16th century many Jews from Portugal and Spain settled in Cochin. These Jews were called white Jews as opposed to the native black Jews.

The Portuguese did not look favorably on the Jews. They destroyed the Jewish settlement in kodungallur and sacked the Jewish town in Cochin and partially destroyed the famous Cochin Synagogue in 1661. However, the Dutch were more tolerant and allowed the Jews to pursue their normal life and trade in Cochin. According to the testimony of the Dutch Jew, Mosss Pereya De Paiva, in 1686 there were 10 synagogues and nearly 500 Jewish families in Cochin. Later Britishers too were tolerant. The Jews were protected. After the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, most Jews decided to emigrate to Israel. Most of the emigrants to Israel between 1948 and 1955 were from the community of black Jews and brown Jews; they are known as Cochini in Israel. Since the 1960s, only a few hundred Jews (mostly white Jews) remained in Kerala with only two synagogues open for service: the Pardesi Synagogue in Matancherry built in 1567 and the synagogue in Parur.

Jainism

Jainism, one of the three most ancient Indian religious traditions still in existence, has very small presence (0.01%) in Kerala, in south India. According to the 2011 India Census, Kerala only has around 4500 Jains, most of them in the city of Cochin and in Wynad district.

Medieval Jain inscriptions are mostly found on the borders of Kerala proper, such Wynad in north-east, Alathur in the Palghat Gap and Chitharal in Kanyakumari District. Epigraphical evidence suggests that the shrine at "Tirukkunavay", perhaps located near Cochin, was the major Jain temple in medieval Kerala (from c. 9th century CE). The so-called "Rules of the Tirukkunavay Temple" provided model and precedent for all other Jain temples of Kerala.[34] A number of images of Mahavira, Padmavati, and Parsvanatha have been recovered from Kerala.[34]

Some of the Jain temples in Kerala were taken over by the Hindus at a later stage. The temple images are worshiped as Hindu gods and considered as part of the Hindu pantheon. It is not uncommon for Hindus and Jains to worship their deities in the same temple.[34]

Christianity

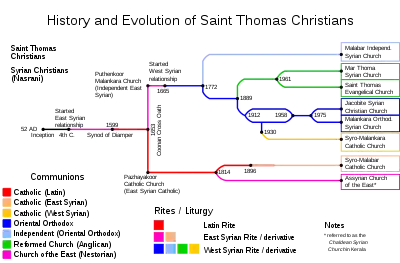

Christianity is followed by 18.38% of the population of Kerala.[35] The Christianity in Kerala has long traditions from first century AD many of which is similar to the Malabari Jews,[36] the latter has settled in Kerala since the King Solomon.[37] According to tradition, Saint Thomas the Apostle visited Muziris in Kerala in the first century in 52 AD and proselytized some then settled Jewish family[38][39] and the natives became Marthoma Nasranis or Saint Thomas Christians.[40][41][42] According to Eusebius' record, Thomas and Bartholomew were assigned to Parthia in ancient India.[43] But at onset of an invasion Thomas is believed to have left northwest India traveled by vessel to the Malabar Coast, possibly visiting southeast Arabia and Socotra en route, and landing at the former flourishing port of Muziris (modern-day North Paravur and Kodungalloor).[39] According to Knanaya Christians, an endogamous ethnic group found among the Saint Thomas Christian community of Kerala, their existence in Kerala is traced back to the arrival of the Syrian merchant Thomas of Cana (Knāi Thoma) who led a migration of Syriac Christians (Jewish-Christians) from Mesopotamia to India in the 4th or 9th century.[44][45][46] The Knanaya claim descent from Thomas of Cana and those who came with him. The communities arrival was recorded on the Thomas of Cana copper plates which existed in Kerala until the 17th century after which point they were taken to Portugal by the Franciscan Order.[47][48][49] Before the arrival of Europeans in Kerala there were only Marthoma Nasranis also called as Malankara Syrian Christians due to its historical, religious, and liturgical connection to Syriac Christianity. Marthoma Nasranis remained as an independent group, and they got their bishops from Church of the East until the advent of Portuguese and British colonialists. The first Roman Catholic Diocese in India was founded at Quilon in the year 1329 with the Catalan Dominican friar Jordanus Catalani as first Bishop.[50] The caste system became prevalent in Kerala later than any other parts of India after fourth and fifth century AD. The Nasranis were given special status outside the Varna system. Like Brahmins they were allowed to sit in front of Kings, ride on horse or elephants, to collect taxes. The Marthoma Nasranis back then also has the role of pollution neutralizers i.e.,if a lower caste person hand over a substance to a Nasrani and if he in turn gives it to an upper caste, say for example Brahmin, then there would be no pollution for that Brahmin.[51]

The arrival of Europeans in the 15th century and discontent with Portuguese interference in religious matters fomented schism into Catholic and Orthodox communities. Further schism and rearrangements led to the formation of the other Indian Churches. Latin Rite Christians has protracted over eleven centuries and the work of evangelization was revived by the western missionaries in the 13th century. Further schism and rearrangements led to the formation of the other Indian Churches. Anglo-Indian Christian communities formed around this time as Europeans and local Malayalis intermarried.

Protestantism arrived a few centuries later with missionary activity during British rule.

There are various denominations/churches exist among Christians of Kerala. Saint Thomas Christians in Kerala are also called Nasranis and they include Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, Malankara Jacobite Syriac Orthodox Church, Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Syrian Church, Saint Thomas Anglicans, Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, Marthoma Syrian Church, St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India and many Pentecostals and Neocharismatics.[52][53]

Around 61% of Christians in the state are Catholics and they are Latin Catholic Church, Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.[54] Orthodox Communities are Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and Malankara Jacobite Syriac Orthodox Church. The Church of South India and Mar Thoma Syrian Church belong to the Anglican Communion.

The major Pentecostal denominations in Kerala are,

- India Pentecostal Church of God

- Assemblies of God in India

- Church of God (Full Gospel) in India

- The Pentecostal Mission

Some of the prominent churches are: St. Thomas Syro-Malabar Church, Malayattoor St. George's Forane Church, St Mary's church, Manarcad, St. Thomas Church, Kothamangalam , St. Mary's Church, Niranam, St. Peter and St. Paul's Church, Parumala, St. George Orthodox Church Puthuppally Pally, St. Stanislaus Forane Church, Mala, St. George's Church, Kadamattom, Marthoman Cathedral, Mulanthuruthy, Chengannur Pazhaya Suriyani Pally, Kozhencherry St. Thomas Marthoma Church, Nilakkal St. Thomas Ecumenical Church and Mother of God Church, Vettukad

Buddhism

Buddhism probably flourished for 200 years (650-850) in Kerala. The Paliyam Copper Plate of the Ay King, Varaguna (885-925 AD)[55] shows that the Buddhists benefited from royal patronage in the 10th century.

Parsi (Zoroastrianism)

There were a number of Parsi families settled in Kerala, particularly around Kozhikode and Thalassery area. They practiced Zoroastrianism and even built the 160-year-old dadgah (fire temple) at Kozhikode which is still in existence. They were mostly wealthy families who immigrated during the 18th century from Gujarat and Bombay. The community included famous families such as the Hirjis or Marshalls.[56] Some famous Malayali Parsis included the reputed Dr. Kobad Mogaseb, who was the first medical doctor from Kozhikode who graduated from London, as well as Kaikose Rudreshan who funded the Basel Evangelical Mission Parsi High School, Thalassery.[57]

Tribal and other religious faiths

Various groups classified as tribes in Kerala still dominate various remote and hilly areas of Kerala.[58] They have retained various rituals and practices of their ancestors despite influences of mainstream religions.

Demographics

Population by religion, per 2011 census

| Religion | Population | % | Population below 6 yrs of age[59] | % | Dist. with highest Population | Dist. with lowest Population | Population growth since 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hindus | 18,282,492 | 54.73 | 1,632,777 | 47.01 | Thiruvananthapuram | Wayanad | 2.23% |

| Muslims | 8,873,472 | 26.56 | 1,276,104 | 36.74 | Malappuram | Pathanamthitta | 12.84% |

| Christians | 6,141,269 | 18.38 | 546,897 | 15.75 | Ernakulam | Malappuram | 1.38% |

Population by religion, per 2001 census

| Religion | Population | % | Population below 6 yrs of age[3] | % | Dist. with highest Population | Dist. with lowest Population | Population growth since 1991 | Children born per women (TFR)[60] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hindus | 17,883,449 | 56.2 | 1,932,504 | 50.78 | Thiruvananthapuram | Waynad | 7.29% | 1.64 |

| Muslims | 7,863,342 | 24.3 | 1,178,880 | 30.99 | Malappuram | Pathanamthitta | 15.84% | 2.46 |

| Christians | 6,057,427 | 19 | 677,878 | 17.82 | Ernakulam | Malappuram | 7.75% | 1.88 |

Population from 2001 and 2011 census, with percentage by religion for each district

| Districts | Population(2001) | Population(2011) | Percent Hindus | Percent Muslims | Percent Christians |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiruvananthapuram | 3,234,707 | 3,301,427 | 66.94% | 13.72% | 19.10% |

| Kollam | 2,584,118 | 2,635,375 | 64.42% | 19.29% | 15.99% |

| Pathanamthitta | 1,231,577 | 1,197,412 | 56.93% | 4.59% | 38.12% |

| Alappuzha | 2,105,349 | 2,127,789 | 68.64% | 10.55% | 20.45% |

| Kottayam | 1,952,901 | 1,974,551 | 49.81% | 6.41% | 43.48% |

| Idukki | 1,128,605 | 1,108,974 | 48.86% | 7.41% | 43.42% |

| Ernakulam | 3,098,378 | 3,282,388 | 45.99% | 15.67% | 38.03% |

| Thrissur | 2,975,440 | 3,121,200 | 58.42% | 17.07% | 24.27% |

| Palakkad | 2,617,072 | 2,809,934 | 66.76% | 28.93% | 4.07% |

| Malappuram | 3,629,640 | 4,112,920 | 27.60% | 70.24% | 1.98% |

| Kozhikode | 2,878,498 | 3,086,293 | 56.21% | 39.24% | 4.26% |

| Waynad | 786,627 | 817,420 | 49.48% | 28.65% | 21.34% |

| Kannur | 2,412,365 | 2,523,003 | 59.83% | 29.43% | 10.41% |

| Kasargod | 1,203,342 | 1,307,375 | 55.83% | 37.24% | 6.68% |

| Religion | 2018[4] | % | 2017[62] | % | 2016[63] | % | 2015[64] | % | 2014[65] | % | 2013[66] | % | 2012[67] | % | 2011[68] | % | 2010[69] | % | 2009[70] | % | 2008[71] | % | 2007[72] | % | 2006[73] | % | 2005[74] | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muslim | 213,805 | 43.80% | 216,525 | 43.00% | 211,182 | 42.55% | 213,865 | 41.45% | 218,437 | 40.87% | 214,257 | 39.96% | 175,892 | 31.96% | 214,099 | 38.21% | 209,276 | 38.26% | 204,711 | 37.61% | 194,583 | 36.32% | 183,796 | 33.71% | 196,493 | 35.32% | 191,675 | 34.28% |

| Hindu | 203,158 | 41.61% | 210,071 | 41.71% | 207,831 | 41.88% | 221,220 | 42.87% | 231,031 | 43.23% | 236,420 | 44.08% | 214,591 | 38.99% | 248,610 | 44.37% | 246,297 | 45.03% | 247,707 | 45.51% | 241,305 | 45.04% | 250,094 | 45.88% | 258,119 | 46.40% | 262,976 | 47.04% |

| Christian | 69,844 | 14.31% | 75,335 | 14.96% | 76,205 | 15.35% | 79,565 | 15.42% | 83,616 | 15.65% | 84,660 | 15.78% | 102,546 | 18.63% | 94,664 | 16.90% | 88,936 | 16.26% | 90,451 | 16.62% | 94,175 | 17.58% | 98,220 | 18.02% | 96,469 | 17.34% | 98,353 | 17.59% |

| Others | 1,214 | 0.25% | 1,497 | 0.30% | 852 | 0.18% | 933 | 0.18% | 1,178 | 0.22% | 869 | 0.16% | 57,215 | 10.39% | 2,671 | 0.48% | 651 | 0.12% | 704 | 0.13% | 5,151 | 0.96% | 6,108 | 1.12% | 1,545 | 0.28% | 1,098 | 0.19% |

| Not Stated | 153 | 0.03% | 160 | 0.03% | 222 | 0.04% | 430 | 0.08% | 196 | 0.03% | 146 | 0.02% | 167 | 0.03% | 224 | 0.04% | 1,806 | 0.33% | 775 | 0.14% | 524 | 0.10% | 6,936 | 1.27% | 3,700 | 0.66% | 4,980 | 0.89% |

| Total | 488,174 | 100% | 503,588 | 100% | 496,292 | 100% | 516,013 | 100% | 534,458 | 100% | 536,352 | 100% | 550,411 | 100% | 560,268 | 100% | 546,964 | 100% | 544,348 | 100% | 535,738 | 100% | 545,154 | 100% | 556,326 | 100% | 559,082 | 100% |

References

- "Population by religious community - 2011". 2011 Census of India. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- "Population by religious communities – Census of India". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "Increase in Muslim population in the State". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 23 September 2004.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2018, Page Number 92" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- "Vidyarambham celebrated in Kerala - India News - IBNLive". Ibnlive.in.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- Panikkar, K. N., Against Lord and State: Religion and Peasant Uprisings in Malabar 1836–1921

- T. Nandakumar, "54.72 % of population in Kerala are Hindus" The Hindu August 26, 2015

- Miller, E. Roland. "Mappila Muslim Culture" State University of New York Press, Albany (2015); p. xi.

- Miller, Roland. E., "Mappila" in "The Encyclopedia of Islam". Volume VI. E. J. Brill, Leiden. 1987 pp. 458-56.

- Pg 461, Roland Miller, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol VI , Brill 1988

- Kunhali, V. "Muslim Communities in Kerala to 1798" PhD Dissertation Aligarh Muslim University (1986)

- Sethi, Atul (24 June 2007). "Trade, not invasion brought Islam to India". Times of India. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Katz 2000; Koder 1973; Thomas Puthiakunnel 1973; David de Beth Hillel, 1832; Lord, James Henry 1977.

- Varghese, Theresa (2006). Stark World Kerala. Stark World Pub. ISBN 9788190250511.

- Kumar, Satish (27 February 2012). India's National Security: Annual Review 2009. Routledge. ISBN 9781136704918.

- Minu Ittyipe; Solomon to Cheraman; Outlook Indian Magazine; 2012

- Menon, A. Sreedhara (1982). The Legacy of Kerala (Reprinted ed.). Department of Public Relations, Government of Kerala. ISBN 978-8-12643-798-6. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- Mehrdad Shokoohy (29 July 2003). Muslim Architecture of South India: The Sultanate of Ma'bar and the Traditions of the Maritime Settlers on the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts (Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Goa). Psychology Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-415-30207-4. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Miller, E. Roland. "Mappila Muslim Culture" State University of New York Press, Albany (2015); p. xi.

- Miller, R. E. "Mappila" in The Encyclopedia of Islam Volume VI. Leiden E. J. Brill 1988 p. 458-66

- Prange, Sebastian R. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Prange, Sebastian R. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Miller, R. E. "Mappila" in The Encyclopedia of Islam Volume VI. Leiden E. J. Brill 1988 p. 458-66

- Nossiter, Thomas Johnson (January 1982). Communism in Kerala: A Study in Political Adaptation. ISBN 9780520046672. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Nossiter, Thomas Johnson (January 1982). Communism in Kerala: A Study in Political Adaptation. ISBN 9780520046672. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Nossiter, Thomas Johnson (January 1982). Communism in Kerala: A Study in Political Adaptation. ISBN 9780520046672. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Pg 461, Roland Miller, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol VI , Brill 1988

- Miller, E. Roland. "Mappila Muslim Culture" State University of New York Press, Albany (2015); p. xi.

- Miller, R. E. "Mappila" in The Encyclopedia of Islam Volume VI. Leiden E. J. Brill 1988 p. 458-66

- India Census 2011 Kerala Government Official Portal

- Nossiter, T. J. "Communism in Kerala: A Study in Political Adaptation" C. Hurst and Company, London (1982) p. 23-25

- Katz 2000; Koder 1973; Thomas Puthiakunnel 1973; David de Beth Hillel, 1832; Lord, James Henry 1977.

- "Sharon delighted with gift from Kochi". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 11 September 2003.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Political and Social Conditions of Kerala Under the Cēra Perumāḷs of Makōtai (c. AD 800 - AD 1124). Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 340-42.

- "2011 Census of India. C-1 Population By Religious Community". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Frykenberg. 2008. p. 99.

- The Jews of India: A story of Three Communities. Israel Museum: UPNE. 1995. p. 27. ISBN 978-965-278-179-6.

- Mundadan & Thekkedath. 1982. pp. 30–32.

- "History | PAYYAPPILLY PALAKKAPPILLY NASRANI". www.payyappilly.org. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 5 by Erwin Fahlbusch. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing - 2008. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-8028-2417-2.

- Medlycott, A E. 1905 "India and the Apostle Thomas"; Gorgias Press LLC; ISBN

- Stephen Neill (2 May 2002). A History of Christianity in India: 1707–1858. Cambridge University Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-521-89332-9. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Medlycott. 1905. pp. 18–71.

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (8 December 2003). The Church of the East. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203423097. ISBN 978-0-203-42309-7.

- "Author Index Vol. 60, 2005". Human Heredity. 60 (4): 242. 2005. doi:10.1159/000091316. ISSN 0001-5652. S2CID 202648744.

- Wallich, Paul (June 1990). "Peary Redux". Scientific American. 262 (6): 25–26. Bibcode:1990SciAm.262f..25W. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0690-25. ISSN 0036-8733.

- "Socialist Politics Post-Mitterrand 1988â2002", Exceptional Socialists, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, doi:10.1057/9781137318688.0012, ISBN 978-1-137-31868-8, retrieved 24 October 2020 C1 control character in

|title=at position 41 (help) - "Obesitasrichtlijnen". Huisarts en Wetenschap. 48 (7): 497. July 2005. doi:10.1007/bf03084328. ISSN 0018-7070.

|first1=missing|last1=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Mundadan AM (1984). Volume I: From the Beginning up to the Sixteenth Century (up to 1542). History of Christianity in India. Church History Association of India. Bangalore: Theological Publications.

- "Index - Quilon DIocese". www.quilondiocese.com. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- Varghese, Philip (2010). Introduction to Caste in Christianity: A Case of Kerala. p. 12. SSRN 2694487.

- Anderson, Allan; Tang, Edmond. Asian and Pentecostal: The Charismatic Face of Christianity in Asia. OCMS. pp. 192 to 193, 195 to 196, 203 to 204. ISBN 978-1-870345-43-9.

- Bergunder, Michael. The South Indian Pentecostal Movement in the Twentieth Century. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 15 to 16, 26 to 30, 37 to 57. ISBN 978-0-8028-2734-0.

- http://cds.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/WP468.pdf

- A social history of India S. N. Sadasivan APH Publishing, 2000

- "Kozhikode's Parsi legacy". The Hindu (www.thehindu.com). Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Thalassery, Team. "THALASSERY - Education - BEMP Higher Secondary school". www.thalassery.info. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- Idukki - People and culture - Tribes

- http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/Religion_PCA.html

- "Population Research and Policy Review, Volume 22, Numbers 5-6". SpringerLink. doi:10.1023/B:POPU.0000020963.63244.8c. S2CID 154895913. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Vital Statistics Reports". Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2017, Page Number 90" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- http://www.ecostat.kerala.gov.in/images/pdf/publications/Vital_Statistics/data/vital_statistics_2016.pdf

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2015, Page Number 21" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2014, Page Number 22" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2013, Page Number 22" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2012, Table – 2.7 (a), Page Number 23" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2011, Table – 2.7 (a), Page Number 23" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2010, Table – 2.7 (a), Page Number 23-24" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2009, Table – 2.7 (a), Page Number 19-20" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2008, Table – 1.7 (a), Page Number 19-20" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2007, Table – 1.7 (a), Page Number 16" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2006, Table – 1.7 (a), Page Number 34" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 2006. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "Annual Vital Statistics Report – 2005, Table – 1.7 (a), Page Number 28" (PDF). Government of Kerala, Vital Statistics Division Department of Economics & Statistics Thiruvananthapuram. Retrieved 2005. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)

.svg.png.webp)