Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas (Spanish: República de Tejas) was a sovereign state in North America that existed from March 2, 1836, to February 19, 1846, although Mexico considered it a rebellious province during its entire existence. It was bordered by Mexico to the west and southwest, the Gulf of Mexico to the southeast, the two U.S. states of Louisiana and Arkansas to the east and northeast, and United States territories encompassing parts of the current U.S. states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico to the north and west. The citizens of the republic were known as Texians.

| 1836–1846 | |

Motto: | |

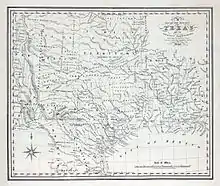

Map of the Republic of Texas. The disputed area is in light green, while the Republic is in dark green. | |

| Capital |

|

| Common languages | English and Spanish |

| Spoken languages | French, German, Portuguese, Native languages (Caddo, Comanche) |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

| President1 | |

• 1836 | David G. Burnet |

• 1836–38 | Sam Houston, 1st term |

• 1838–41 | Mirabeau B. Lamar |

• 1841–44 | Sam Houston, 2nd term |

• 1844–46 | Anson Jones |

| Vice President1 | |

• 1836 | Lorenzo de Zavala |

• 1836–38 | Mirabeau B. Lamar |

• 1838–41 | David G. Burnet |

• 1841–44 | Edward Burleson |

• 1844–45 | Kenneth L. Anderson |

| Legislature | Congress |

• Upper house | Senate |

• Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Historical era | Western Expansion |

| March 2, 1836 | |

| December 29, 1845 | |

• Transfer of power | February 19, 1846 |

| Area | |

| 1840 | 1,007,935 km2 (389,166 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1840 | 70,000 |

| Currency | Texan dollar |

| Today part of |

|

1Interim period (March 16 – October 22, 1836): President: David G. Burnet, Vice President Lorenzo de Zavala | |

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

The region of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas, now commonly referred to as Mexican Texas, declared its independence from Mexico during the Texas Revolution in 1835–1836, when the Centralist Republic of Mexico abolished autonomy from states of the Mexican federal republic. The major fighting in the Texas war of independence ended on April 21, 1836, but the Mexican Congress refused to recognize the independence of the Republic of Texas, since the agreement was signed by Mexican President General Antonio López de Santa Anna under duress as prisoner of the Texians. There were intermittent conflicts between Mexico and Texas into the 1840s. The United States recognized the Republic of Texas in March 1837 but declined to annex the territory.[3]

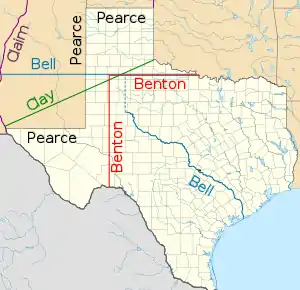

The Republic-claimed borders were based upon the Treaties of Velasco between the newly created Texas Republic and General Santa Anna, who had been captured in battle. The eastern boundary had been defined by the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819 between the United States and Spain, which recognized the Sabine River as the eastern boundary of Spanish Texas and western boundary of the Missouri Territory. Under the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty, before Mexico's 1821 independence, the United States had renounced its claim to Spanish land to the east of the Rocky Mountains and to the north of the Rio Grande, which it claimed to have acquired as part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

The republic's southern and western boundary with Mexico was disputed throughout the republic's existence, since Mexico disputed the independence of Texas. Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its southern boundary, while Mexico insisted that the Nueces River was the boundary. In practice, much of the disputed territory was occupied by the Comanche and outside the control of either state, but Texian claims included the eastern portions of New Mexico, which was administered by Mexico throughout this period.

Texas was annexed by the United States on December 29, 1845[4] and was admitted to the Union as the 28th state on that day, with the transfer of power from the Republic to the new state of Texas formally taking place on February 19, 1846.[5] However, the United States inherited the southern and western border dispute with Mexico, which had refused to recognize Texas's independence or U.S. offers to purchase the territory. Consequently, the annexation triggered the Mexican–American War (1846–1848).

History

Spanish Texas

During the late Spanish colonial era, Texas had been one of the Provincias Internas, and the region is known in the historiography as Spanish Texas. Though claimed by Spain, it was not formally colonized by the empire until competing French interests at Fort St. Louis encouraged Spain to establish permanent settlements in the area.[6] The region was occupied and claimed by the existing indigenous groups. Sporadic missionary incursions occurred into the area during the period from the 1690s–1710s, before the establishment of San Antonio as a permanent civilian settlement.[7] Owing to the area's relatively dense Native American populations, its remoteness from the population centers of New Spain, and the lack of any obvious valuable resources such as silver, Texas had only a small European population, although Spain maintained a small military presence to protect Christian missionaries working among Native American tribes, and to act as a buffer against the French in Louisiana and British North America.

In 1762, Bourbon France ceded to Bourbon Spain most of its claims to the interior of North America, including its claim to Texas, as well as the vast interior that became Spanish Louisiana.[8] During the years 1799 to 1803, the height of the Napoleonic Empire in France, Spain returned Louisiana to France, which then promptly sold the territory to the United States. The status of Texas during these transfers was unclear and was not resolved until 1819, when the Adams–Onís Treaty between Spain and the United States ceded Spanish Florida to the United States, and established a clear boundary between Texas and Louisiana.[9]

Starting in 1810 with the outbreak of the Mexican War of Independence, New Spain sought a different relationship with the Spanish crown. Some Anglo Americans fought on the side of Mexico against Spain in filibustering expeditions. One of these, the Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition (also known as the Republican Army of the North) comprised by a group of about 130 Anglo Americans under the leadership of Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara. Gutiérrez de Lara initiated Mexico's secession from Spain with efforts contributed by Augustus Magee. Bolstered by new recruits, and led by Samuel Kemper (who succeeded Magee after his death in battle in 1813), the expedition gained a series of victories against soldiers led by the Spanish governor, Manuel María de Salcedo.

Their victory at the Battle of Rosillo Creek convinced Salcedo to surrender on April 1, 1813; he was executed two days later. On April 6, 1813, the victorious Republican Army of the North drafted a constitution and declared the independent Republic of Texas, with Gutiérrez as its president.[10] Soon disillusioned with the Mexican leadership, the Anglo Americans under Kemper returned to the United States.

The ephemeral Republic of Texas came to an end on August 18, 1813, with the Battle of Medina, where the Spanish Army crushed the Republican Army of the North. The harsh reprisals against the Texas rebels created a deep distrust of the Royal Spanish authorities, and veterans of the Battle of Medina later became leaders of the Texas Revolution and signatories of the Texas Declaration of Independence from Mexico 20 years later.

After the failure of the Expedition, there would be no serious push for a "Republic of Texas" for another six years, until 1819, when Virginian filibuster Dr. James Long invaded Spanish Texas in an attempt to "liberate" the region.

Eli Harris led 120 men across the Sabine River to Nacogdoches. Long followed two weeks later with an additional 75 men. On June 22, the combined force declared a new government, with Long as president and a 21-member Supreme Council. The following day, they issued a declaration of independence, modeled on the United States Declaration of Independence. The document cited several grievances, including "Spanish rapacity" and "odious tyranny" and promised religious freedom, freedom of the press, and free trade. The council also allocated 10 square miles of land to each member of the expedition, and authorized the sale of additional land to raise cash for the fledgling government. Within a month, the expedition had grown to 300 members.

The new government established trading outposts near Anahuac along the Trinity River and the Brazos River. They also began the first English-language newspaper ever published in Texas, so named the Texas Republican, which existed only for the month of August 1819.

Long also contacted Jean Lafitte, who ran a large smuggling operation on Galveston Island. His letter suggested that the new government establish an admiralty court at Galveston, and offered to appoint Lafitte governor of Galveston. Unbeknownst to Long, Lafitte was actually a Spanish spy. While making numerous promises–and excuses–to Long, Lafitte gathered information about the expedition and passed it on to Spanish authorities. By July 16, the Spanish Consul in New Orleans had warned the viceroy in Mexico City that "I am fully persuaded that the present is the most serious expedition that has threatened the Kingdom".

With Lafitte's lack of assistance, the expedition soon ran low on provisions. Long dispersed his men to forage for food. Discipline began to break down, and many men, including Bowie, returned home. In early October, Lafitte reached an agreement with Long to make Galveston an official port for the new country and name Lafitte governor. Within weeks, 500 Spanish troops arrived in Texas and marched on Nacogdoches. Long and his men withdrew. Over 40 men were captured. Long escaped to Natchitoches, Louisiana. Others fled to Galveston and settled along Bolivar Peninsula.

Undeterred in his defeat, Dr. Long returned once more in 1820, Long joined the refugees at Bolivar Peninsula on April 6, 1820, with more reinforcements. He continued to raise money to equip a second expedition. Fifty men attempted to join him from the United States, but they were arrested by American authorities as they tried to cross into Texas. The men who had joined Long were disappointed they were paid in scrip, and they gradually began to desert. By December 1820, Long commanded only 50 men.

With the aid of Ben Milam and others, Long revitalized the Supreme Council. He later broke with Milam, and the expedition led an uncertain existence until September 19, 1821, when Long and 52 men marched inland to capture Presidio La Bahía. The town fell easily on October 4, but four days later Long was forced to surrender by Spanish troops. He was taken prisoner and sent to Mexico City, where about six months later he was shot and killed by a guard – reportedly bribed to do so by José Félix Trespalacios, thus ending the Long Expeditions.

Mexican Texas

Along with the rest of Mexico, Texas gained its independence from Spain in 1821 following the Treaty of Córdoba, and the new Mexican state was organized under the Plan of Iguala, which created Mexico as a constitutional monarchy under its first Emperor Agustín de Iturbide. During the transition from a Spanish territory to a part of the independent country of Mexico, Stephen F. Austin led a group of American settlers known as the Old Three Hundred, who negotiated the right to settle in Texas with the Spanish Royal governor of the territory. Since Mexican independence had been ratified by Spain shortly thereafter, Austin later traveled to Mexico City to secure the support of the new country for his right to settle.[11] The establishment of Mexican Texas coincided with the Austin-led settlement, leading to animosity between Mexican authorities and ongoing American settlement of Texas. The First Mexican Empire was short-lived, being replaced by a republican form of government in 1823. In 1824, the sparsely populated territories of Texas and Coahuila were joined to form the state of Coahuila y Tejas. The capital was controversially located in southern Coahuila, the part farthest from Texas.

Following Austin's lead, additional groups of settlers, known as Empresarios, continued to colonize Mexican Texas from the United States. A spike in the price of cotton, and the success of plantations in Mississippi encouraged large numbers of white Americans to migrate to Texas and obtain slaves to try to replicate the business model.[12] In 1830, Mexican President Anastasio Bustamante outlawed American immigration to Texas, following several conflicts with the Empresarios over the status of slavery, which had been abolished in Mexico in 1829, but which the Texans refused to end.[13] Texans replaced slavery with long-term indentured servitude contracts signed by "liberated" slaves in the United States to work around the abolition of slavery. Angered at the interference of the Mexican government, the Empresarios held the Convention of 1832, which was the first formal step in what became the Texas Revolution.[14]

By 1834, the American settlers in the area outnumbered Mexicans by a considerable margin.[15] Following a series of minor skirmishes between Mexican authorities and the settlers, the Mexican government, fearing open rebellion of their Anglo subjects, began to step up military presence in Texas throughout 1834 and early 1835. Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna revoked the 1824 Constitution of Mexico and began to consolidate power in the central government under his own leadership. In 1835, the central government split Texas and Coahuila into two separate departments. The Texian leadership under Austin began to organize its own military, and hostilities broke out on October 2, 1835, at the Battle of Gonzales, the first engagement of the Texas Revolution.[16] In November 1835, a provisional government known as the Consultation was established to oppose the Santa Anna regime (but stopped short of declaring independence from Mexico). On March 1, 1836 the Convention of 1836 came to order, and the next day declared independence from Mexico, establishing the Republic of Texas.[17]

Politics

.jpg.webp)

_UTA.jpg.webp)

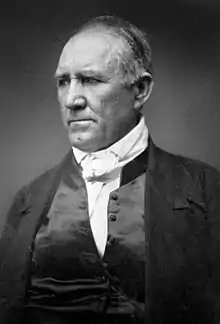

Sam Houston was elected as the new President of the Republic of Texas on September 5, 1836.[18] The second Congress of the Republic of Texas convened a month later, in October 1836, at Columbia (now West Columbia). Stephen F. Austin, known as the Father of Texas, died December 27, 1836, after serving two months as Secretary of State for the new Republic.

In 1836, five sites served as temporary capitals of Texas (Washington-on-the-Brazos, Harrisburg, Galveston, Velasco and Columbia), before President Sam Houston moved the capital to Houston in 1837. The next president, Mirabeau B. Lamar, moved the capital to the new town of Austin in 1839.

The first flag of the republic was the "Burnet Flag" (a single gold star on an azure field), followed in 1839 by official adoption of the Lone Star Flag.

Internal politics of the Republic centered on two factions. The nationalist faction, led by Lamar, advocated the continued independence of Texas, the expulsion of the Native Americans (Indians), and the expansion of Texas to the Pacific Ocean. Their opponents, led by Houston, advocated the annexation of Texas to the United States and peaceful coexistence with the Indians, when possible. The Texas Congress even passed a resolution over Houston's veto claiming the Californias for Texas.[19] The 1844 presidential election split the electorate dramatically, with the newer western regions of the Republic preferring the nationalist candidate Edward Burleson, while the cotton country, particularly east of the Trinity River, went for Anson Jones.[20]

Armed conflicts

The Comanche Indians furnished the main Indian opposition to the Texas Republic, manifested in multiple raids on settlements, capture, and rape of female pioneers, torture killings, and trafficking in captive slaves.[21] In the late 1830s, Sam Houston negotiated a peace between Texas and the Comanches. Lamar replaced Houston as president in 1838 and reversed the Indian policies. He returned to war with the Comanches and invaded Comancheria itself. In retaliation, the Comanches attacked Texas in a series of raids. After peace talks in 1840 ended with the massacre of 34 Comanche leaders in San Antonio, the Comanches launched a major attack deep into Texas, known as the Great Raid of 1840. Under command of Potsanaquahip (Buffalo Hump), 500 to 700 Comanche cavalry warriors swept down the Guadalupe River valley, killing and plundering all the way to the shore of the Gulf of Mexico, where they sacked the towns of Victoria and Linnville. The Comanches retreated after being pursued by 186 rangers, and were caught at the Battle of Plum Creek wherein they lost the plunder they had taken.[22] Houston became president again in 1841 and, with both Texians and Comanches exhausted by war, a new peace was established.[23]

Although Texas achieved self-government, Mexico refused to recognize its independence.[24] On March 5, 1842, a Mexican force of over 500 men, led by Ráfael Vásquez, invaded Texas for the first time since the revolution. They soon headed back to the Rio Grande after briefly occupying San Antonio. About 1,400 Mexican troops, led by the French mercenary general Adrián Woll, launched a second attack and captured San Antonio on September 11, 1842. A Texas militia retaliated at the Battle of Salado Creek while simultaneously, a mile and a half away, Mexican soldiers massacred a militia of fifty-three Texas volunteers who had surrendered after a skirmish.[25][26] That night, the Mexican Army retreated from the city of San Antonio back to Mexico.

Mexico's attacks on Texas intensified conflicts between political factions, including an incident known as the Texas Archive War. To "protect" the Texas national archives, President Sam Houston ordered them removed from Austin. The archives were eventually returned to Austin, albeit at gunpoint. The Texas Congress admonished Houston for the incident, and this episode in Texas history solidified Austin as Texas's seat of government for the Republic and the future state.[27]

There were also domestic disturbances. The Regulator–Moderator War involved a land feud in Harrison and Shelby Counties in East Texas from 1839 to 1844. The feud eventually involved Nacogdoches, San Augustine, and other East Texas counties. Harrison County Sheriff John J. Kennedy and county judge Joseph U. Fields helped end the conflict, siding with the law-and-order party. Sam Houston ordered 500 militia to help end the feud.

Criteria of citizenship

Citizenship was not automatically granted to all previous inhabitants of Texas and some residents were not allowed to continue living legally within the Republic without the consent of Congress. The Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836) established different rights according to the race and ethnicity of each individual. Section 10 of the General Provisions of the Constitution stated that all persons who resided in Texas on the day of the Declaration of Independence were considered citizens of the Republic, excepting "Africans, the descendants of Africans, and Indians."[28] For new white immigrants, section 6 established that, to become citizens, they needed to live in the Republic for at least six months and take an oath. While regarding the black population, section 9 established that black persons who were brought to Texas as slaves were to remain slaves and that not even their owner could emancipate them without the consent of Congress. Furthermore, the Congress was not allowed to make laws that affected the slave trade or declare emancipation. Section 9 also established that: "No free person of African descent, either in whole or in part, shall be permitted to reside permanently in the Republic, without the consent of Congress."[29]

Government

In September, 1836 Texas elected a Congress of 14 senators and 29 representatives. The Constitution allowed the first president to serve for two years and subsequent presidents for three years. To hold an office or vote, a man had to be a citizen of the Republic.[30]

The first Congress of the Republic of Texas convened in October 1836 at Columbia (now West Columbia). Stephen F. Austin, often referred to as the "Father of Texas," died on December 27, 1836, after serving just two months as the republic's secretary of state. Due mainly to the ongoing war for independence, five sites served as temporary capitals of Texas in 1836: (Washington-on-the-Brazos, Harrisburg, Galveston, Velasco and Columbia). The capital was moved to the new city of Houston in 1837.

In 1839, a small pioneer settlement situated on the Colorado River in central Texas was chosen as the republic's seventh and final capital. Incorporated under the name Waterloo, the town was renamed Austin shortly thereafter in honor of Stephen F. Austin.

The court system inaugurated by Congress included a Supreme Court consisting of a chief justice appointed by the president and four associate justices, elected by a joint ballot of both houses of Congress for four-year terms and eligible for re-election. The associates also presided over four judicial districts. Houston nominated James Collinsworth to be the first chief justice. The county-court system consisted of a chief justice and two associates, chosen by a majority of the justices of the peace in the county. Each county was also to have a sheriff, a coroner, justices of the peace, and constables to serve two-year terms. Congress formed 23 counties, whose boundaries generally coincided with the existing municipalities. In 1839, Texas became the first nation in the world to enact a homestead exemption, under which creditors cannot seize a person's primary residence.

Education

President Anson Jones signed the charter for Baylor University in the fall of 1845.[31] Henry Lee Graves was elected Baylor's first president. It is believed to be the oldest university in Texas, however, Rutersville College was chartered in 1840 with land and the town of Rutersville.[32] Chauncey Richardson[33] was elected Rutersville's first president. The college later became Southwestern University in Georgetown, Fayette county.[33] University of Mary Hardin-Baylor was also chartered by the Republic of Texas in 1845, and received lands in Belton, Texas.[34] Wesleyan College, chartered in 1844 and signed by president Sam Houston, another predecessor to Southwestern did not survive long due to competition from other colleges.[35] Mirabeau Lamar signed a charter in 1844 for the Herman University for medicine but classes never started due to lack of funds.[36] The University of San Augustine was chartered June 5, 1837, but did not open until 1842 when Marcus A. Montrose became president. There were as many as 150 students enrolled, however, attendance declined to 50 in 1845, and further situations including animosity and embittered factions in the community closed the university in 1847.[37] Later it became the University of East Texas, and soon after that became the Masonic Institute of San Augustine in 1851. Guadalupe College at Gonzales was approved January 30, 1841, however, there were no construction efforts ensued for the next eleven years.[38]

Boundaries

.svg.png.webp)

The Texian leaders at first intended to extend their national boundaries to the Pacific Ocean, but ultimately decided to claim the Rio Grande as boundary, including much of New Mexico, which the Republic never controlled. They also hoped, after peace was made with Mexico, to run a railroad to the Gulf of California to give "access to the East Indian, Peruvian and Chilean trade".[39] When negotiating for the possibility of annexation to the U.S. in late 1836, the Texian government instructed its minister Wharton in Washington that if the boundary were an issue, Texas was willing to settle for a boundary at the watershed between the Nueces River and Rio Grande, and leave out New Mexico.[40]

In 1840 the first and only census of the Republic of Texas was taken, recording a population of about 70,000 people. San Antonio and Houston were recorded as the largest and second largest cities respectively.

Diplomatic relations and foreign trade

Texas' status as a slaveholding country and Mexico's claim on the territory caused significant problems in the foreign relations of Texas, with Mexico lobbying third countries not to aid the breakaway republic.[12]

Though supported by the vast majority of the population of Texas at the time of independence, annexation by the United States was prevented by the leadership of both major U.S. political parties, the Democrats and the Whigs. They opposed the introduction of a vast slave-holding region into a country already divided into pro- and anti-slavery sections, and also wished to avoid a war with Mexico.

On March 3, 1837, US President Andrew Jackson appointed Alcée La Branche American chargé d'affaires to the Republic of Texas, thus officially recognizing Texas as an independent republic.[41] France granted official recognition of Texas on September 25, 1839, appointing Alphonse Dubois de Saligny to serve as chargé d'affaires. The French Legation was built in 1841, and still stands in Austin as the oldest frame structure in the city.[42] Conversely, the Republic of Texas embassy in Paris was located in what is now the Hôtel de Vendôme, adjacent to the Place Vendôme in the 1st arrondissement of Paris.[43]

The Republic also received diplomatic recognition from Belgium, the Netherlands, and the Republic of Yucatán. The United Kingdom never granted official recognition of Texas due to its own friendly relations with Mexico, but admitted Texian goods into British ports on their own terms. In London, immediately opposite the gates to St. James's Palace, Sam Houston's original Embassy of the Republic of Texas to the Court of St. James's is now a hat shop but is clearly marked with a large plaque and there was a nearby restaurant by Trafalgar Square called the Texas Embassy Cantina but it closed in June 2012.[44] A plaque on the exterior of 3 St. James's Street in London notes the upper floors of the building (which have housed the noted wine merchant Berry Brothers and Rudd since 1698) housed the Texas Legation.

The United Kingdom recognized Texas in the 1840s after a cotton price crash, in a failed attempt to coerce Texas to give up slavery (replacing slave-produced cotton from southern U.S. states), and to stop expansion of the United States to the southwest.[12] The cotton price crash of the 1840s bankrupted the Republic, increasing the urgency of finding foreign allies who could help prevent a reconquest by Mexico.[12]

Presidents and vice presidents

| Presidents and Vice Presidents of the Republic of Texas | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Portrait | President | Term of Office | Party | Term | Previous Office | Vice President |

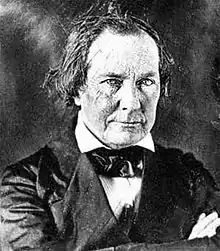

| — |  |

David G. Burnet April 18, 1788 – December 5, 1870 (aged 82) |

March 16, 1836 – October 22, 1836 |

Nonpartisan | Interim |

Delegate to the Convention of 1833 |

Lorenzo de Zavala |

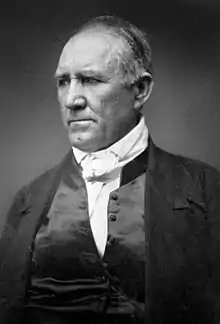

| 1 |  |

Sam Houston March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863 (aged 70) |

October 22, 1836 – December 10, 1838 |

Nonpartisan | 1 (1836) |

Commander-in-Chief of the Texian Army (1836) |

Mirabeau B. Lamar |

| 2 |  |

Mirabeau B. Lamar August 16, 1798 – December 19, 1859 (aged 61) |

December 10, 1838 – December 13, 1841 |

Nonpartisan | 2 (1838) |

1st Vice President of the Republic of Texas (1836–1838) |

David G. Burnet |

| 3 |  |

Sam Houston March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863 (aged 70) |

December 13, 1841 – December 9, 1844 |

Nonpartisan | 3 (1841) |

1st President of the Republic of Texas (1836–1838) |

Edward Burleson |

| 4 |  |

Anson Jones January 20, 1798 – January 9, 1858 (aged 59) |

December 9, 1844 – February 19, 1846 |

Nonpartisan | 4 (1844) |

11th Secretary of State of the Republic of Texas (1841–1844) |

Kenneth Anderson December 9, 1844 – July 3, 1845 |

Statehood

On February 28, 1845, the US Congress passed a bill that authorized the United States to annex the Republic of Texas. On March 1, US President John Tyler signed the bill. The legislation set the date for annexation for December 29 of the same year. Faced with imminent American annexation of Texas, Charles Elliot and Alphonse de Saligny, the British and French ministers to Texas, were dispatched to Mexico City by their governments. Meeting with Mexico's foreign secretary, they signed a "Diplomatic Act" in which Mexico offered to recognize an independent Texas with boundaries determined with French and British mediation. Texas President Anson Jones forwarded both offers to a specially elected convention meeting at Austin, and the American proposal was accepted with only one dissenting vote. The Mexican proposal was never put to a vote. Following the previous decree of President Jones, the proposal was then put to a vote throughout the republic.

On October 13, 1845, a large majority of voters in the republic approved both the American offer and the proposed constitution that specifically endorsed slavery and emigrants bringing slaves to Texas.[45] This constitution was later accepted by the US Congress, making Texas a US state on the same day annexation took effect, December 29, 1845 (therefore bypassing a territorial phase).[46] One of the motivations for annexation was the huge debts which the Republic of Texas government had incurred. As part of the Compromise of 1850, in return for $10,000,000 in Federal bonds, Texas dropped claims to territory that included parts of present-day Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

The resolution did include two unique provisions: First, it said up to four additional states could be created from Texas' territory with the consent of the State of Texas (and that new states north of the Missouri Compromise Line would be free states). Though the resolution did not make exceptions to the constitution,[47] the U.S. Constitution does not require Congressional consent to the creation of new states to be ex post to applications, nor does the U.S. Constitution require applications to expire. To illustrate the strength of the latter caveat, the 27th Amendment was submitted to the states in 1789, yet was not ratified until 1992—thus, the expressed consent of Congress, via this resolution, to the creation of new states would not expire nor require renewal. Second, Texas did not have to surrender its public lands to the federal government. While Texas did cede all territory outside of its current area to the federal government in 1850, it did not cede any public lands within its current boundaries. Consequently, the lands in Texas that the federal government owns are those it subsequently purchased. This also means the state government controls oil reserves, which it later used to fund the state's public university system through the Permanent University Fund.[48] In addition, the state's control over offshore oil reserves in Texas runs out to 3 nautical leagues (9 nautical miles, 10.357 statute miles, 16.668 km) rather than three nautical miles (3.45 statute miles, 5.56 km) as with other states.[49][50]

See also

Notes

- "Texas State Moto - Friendship". wheretexasbecametexas.org. August 4, 2016.

- "Flags of Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- Henderson (2008), p. 121.

- O'Neill, R. (2011). Texas War of Independence. Rosen Publishing Group. p. 85. ISBN 9781448813322.

- Kelly F. Himmel (1999). The Conquest of the Karankawas and the Tonkawas: 1821-1859. Texas A&M University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-89096-867-3.

- Weber, David J. (1992), The Spanish Frontier in North America, Yale Western Americana Series, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, p. 149, ISBN 0-300-05198-0

- Chipman, Donald E. (2010) [1992], Spanish Texas, 1519–1821 (revised ed.), Austin: University of Texas Press, p. 126, ISBN 978-0-292-77659-3

- Weber (1992), p. 198.

- Lewis, James E. (1998), The American Union and the Problem of Neighborhood: The United States and the Collapse of the Spanish Empire, 1783–1829, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, p. 124, ISBN 0-8078-2429-1

- Weber (1992), p. 299.

- Edmondson, J.R. (2000). The Alamo Story-From History to Current Conflicts. Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press. p. 63. ISBN 1-55622-678-0.

- Andrew J. Torget (2015). Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1469624242.

- Robert A. Calvert, Arnoldo De Leon, and Gregg Cantrell, The history of Texas (2014) pp 64-74.

- Eugene C. Barker, The Life of Stephen F. Austin, Founder of Texas (2010) pp 348-50.

- Manchaca (2001), pp. 172, 201.

- Hardin, Stephen L. (1994). Texian Iliad. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-292-73086-1.

- Lack, Paul D. (1992). The Texas Revolutionary Experience: A Political and Social History 1835–1836. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 0-89096-497-1.

- "TSHA | Republic of Texas". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- #Fehrenbach, page 263

- #Fehrenbach, page 265

- This had also been their policy toward neighboring tribes before the arrival of the settlers. Gwinnett, S.C. (2010). Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History. ISBN 978-1-4165-9106-1.

- "Texas Military Forces Museum". Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- Hämäläinen 2008, pp. 215–217.

- Jack W. Gunn, "MEXICAN INVASIONS OF 1842," Handbook of Texas Online, accessed May 24, 2011. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

- Thomas W. Cutrer, "SALADO CREEK, BATTLE OF," Handbook of Texas Online accessed May 24, 2011. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

- "Dawson Massacre". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved September 24, 2006.

- "The Archives War". Texas Treasures – The Republic. The Texas State Library and Archives Commission. November 2, 2005. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- "General Provisions - Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836)". tarlton.law.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- "General Provisions - Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836)". tarlton.law.utexas.edu. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- Davis, William C. (2006). Lone Star Rising. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-58544-532-5. originally published 2004 by New York: Free Press

- "Is Baylor the oldest university in Texas?". February 1, 2016.

- CUSTER, JUDSON S. (June 15, 2010). "RUTERSVILLE COLLEGE". tshaonline.org.

- STONE, WILLIAM J. (June 15, 2010). "RICHARDSON, CHAUNCEY". tshaonline.org.

- "University of Mary Hardin-Baylor". go.umhb.edu.

- ENGLISH, JOHN C. (June 15, 2010). "WESLEYAN COLLEGE". tshaonline.org.

- BROWN, D. CLAYTON (June 15, 2010). "MEDICAL EDUCATION". tshaonline.org.

- YOUNG, NANCY BECK (June 15, 2010). "UNIVERSITY OF SAN AUGUSTINE". tshaonline.org.

- "GUADALUPE COLLEGE LAND GRANT | The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA)". tshaonline.org.

- George Rives, The United States and Mexico vol. 1, page 390

- Rives, p. 403

- "LA BRANCHE, ALCÉE LOUIS". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved Apr.7, 2010.

- Museum Info, French Legation Museum.

- "PARIS 2e: The Paris Embassy of Texas". Parisdeuxieme.com. June 28, 2007. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- "DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS".

- "Article VIII: Slaves - Constitution of Texas (1845) (Joining the U.S.)". Archived from the original on January 16, 2014.

- "The Avalon Project : Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy". Archived from the original on December 5, 2006.

- "Joint Resolution for Annexing Texas to the United States Approved March 1, 1845 - TSLAC".

- Texas Annexation : Questions and Answers, Texas State Library & Archives Commission.

- "U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov.

- "United States v. Louisiana :: 363 U.S. 1 (1960) :: Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center". Justia Law.

References

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Texas | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

- Huson, Hobart (1974), Captain Phillip Dimmitt's Commandancy of Goliad, 1835–1836: An Episode of the Mexican Federalist War in Texas, Usually Referred to as the Texan Revolution, Austin, TX: Von Boeckmann-Jones Co

- Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008), The Comanche Empire, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9

- Lack, Paul D. (1992), The Texas Revolutionary Experience: A Political and Social History 1835–1836, Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 0-89096-497-1

- Fehrenbach, T. R. (2000), Lone Star: a history of Texas and the Texans, Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-80942-2

- Republic of Texas Historical Resources

- Republic of Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Hosted by Portal to Texas History:

- Texas: the Rise, Progress, and Prospects of the Republic of Texas, Vol. 1, by William Kennedy, published 1841

- Texas: the Rise, Progress, and Prospects of the Republic of Texas, Vol. 2, published 1841

- Laws of the Republic, 1836–1838 from Gammel's Laws of Texas, Vol. I.

- Laws of the Republic, 1838–1845 from Gammel's Laws of Texas, Vol. II.

- The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: Texas – From Independence to Annexation

- Early Settlers and Indian Fighters of Southwest Texas by Andrew Jackson Sowell 1900

Further reading

- Hardin, Stephen L.; Wade, Mary Dodson (1998). Lone Star: The Republic of Texas, 1836–1846. Discovery Enterprises. ISBN 978-1-878668-63-9.

- Hogan, William Ransom (2007). The Texas Republic: A Social and Economic History. Texas State Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-87611-220-5. OCLC 76167055.

- Howell, Kenneth W. and Charles Swanlund, eds. Single Star of the West: The Republic of Texas, 1836-1845 (U of North Texas Press; 2017) 550 pages; essays by scholars on its founders, defense, diplomacy, economy, and society, with particular attention to Tejanos, African-Americans, American Indians, and women.

- Lankevich, George J. (1979). The Presidents of the Republic of Texas: Chronology, Documents, Bibliography. Oceana Publications. ISBN 978-0-379-12085-1.

- Martinez de Vara, Art (2020). Tejano Patriot: The Revolutionary Life of Jose Francisco Ruiz, 1783 - 1840. Austin, TX: Texas State Historical Association Press. ISBN 978-1625110589.

- Pletcher, David M. The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War. Columbia: University of Missouri Press 1973. ISBN 0-8262-0135-0

- Siegel, Stanley. A Political History of the Texas Republic, 1836-1845. Austin: University of Texas Press 1956.

- Schmitz, Joseph William. Texan Statecraft,1836-1845. San Antonio 1941.

- Weems, John Edward; Weems, Jane (1971). Dream of Empire: A Human History of the Republic of Texas, 1836–1846. Simon and Schuster.

External links

![]() Media related to Republic of Texas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Republic of Texas at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)