History of Houston

This article documents the wide-ranging history of the city of Houston, the largest city in the state of Texas and the fourth-largest in the United States.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Texas | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

History of Houston | |

|---|---|

| City of Houston | |

Aerial View of downtown Houston, 1951 | |

| Country | |

| State | |

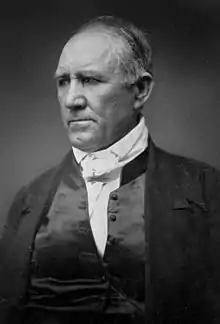

| Named for | Sam Houston |

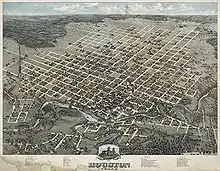

The City of Houston was settled in 1837 after Augustus and John Allen had acquired land to establish a new town at the junction of Buffalo and White Oak bayous in 1836. Houston served as the temporary capital of the Republic of Texas. Meanwhile the town developed as a regional transportation and commercial hub. Houston was part of an independent nation until 1846, when the United States formally annexed Texas. Railroad development began in the late 1850s, but ceased during the American Civil War. Houston served the Confederacy as a regional military logistics center. Population increased during the war and blockade runners used the town as a center for their operations.

Many free blacks came to Houston after the Civil War. Not receiving the support of the incumbent white population, they formed their own social and economic networks. Black residents constituted about twenty percent of the Houston citizenry throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. Investment and development of railroads serving Houston increased the transportation options for freight and passengers, while greatly increasing the number of jobs. The City limits extended to an area north of Buffalo Bayou after the Civil War. Houston continued as an important business, social, and economic center of Texas, while establishing the first State Fair starting in 1870 and continuing through 1878.

The population surpassed 58,000 in 1900, the same year as the Great Hurricane struck Galveston. Within a few years, oil companies were establishing offices in Houston to administer oil fields in East Texas. In 1912, the Rice Institute opened its doors on its suburban campus, the first institute of higher learning in the Houston area. Several tall buildings were completed that year, including those used for offices and residences. Tax Commissioner Joseph Jay Pastoriza gained national notoriety for his property tax reform, though it was later invalidated by the Texas Supreme Court. Around this time Houston started drawing immigrants from Mexico, a trend continuing into the 1920s. Many settled in the Second Ward. During this period, the city developed Hermann Park. Houston gained national prominence when it hosted the Democratic National Convention in 1928.

Before 1836

The region known as Houston is located on land that was once home of the Karankawa (kə rang′kə wä′,-wô′,-wə) and the Atakapa (əˈtɑːkəpə) indigenous peoples for at least 2,000 years before the first known settlers arrived.[1] [2] However, the land remained largely uninhabited until settlement in the 1830s.[3][4]

Republic of Texas, 1836–1845

On the heels of the Texas Revolution, two real estate promoters who had arrived in Texas in 1832, John Kirby Allen and Augustus Chapman Allen, were seeking a new town site within the Galveston Bay navigation system. They had invested in Galveston already, but they continued to make offers for other tracts in the region. They bid on land at Morgan's Point and Harrisburg before settling on the eventual Houston site.[4] On August 26, 1836, they purchased half a league of land, or about 2,214 acres (27 km²) from Elizabeth (Mrs. T. F. L.) Parrot, John Austin's widow for $5,000.[3][4] Four days later, the Allen brothers placed an advertisement in the Telegraph and Texas Register for the paper town of Houston.[5] Gail Borden and his assistant Moses Lapham conducted preliminary surveying work in October, taking field notes and laying stakes.[6] Meanwhile, John Allen was back in Columbia lobbying members of Texas Congress to designate the not yet surveyed town and promising to construct government buildings. On November 30, a special joint session of Congress considered fifteen possible locations for the next seat of government. On the first ballot, ten of these locations garnered votes, but Houston gained a majority of votes on the fourth ballot.[7]

The Allen brothers chose a site at the confluence of White Oak Bayou and Buffalo Bayou, which served as a natural turning basin, now known as Allen's Landing.[8] The Laura, the first steamship ever to visit Houston, arrived in January 1837, at which time the town totaled twelve residents and one log cabin. Four months later there were 1,500 people and 100 houses.[9] Critical to the promotion of Houston by the Allen brothers was the importance of its location as a natural logistical center. They claimed that the town lay at the "head of navigation" on Buffalo Bayou. Their critics cast doubt on the navigability of Buffalo Bayou as far upstream as Houston, who had not been convinced by the arrival of the Laura. A true test would be a larger ship making the trip.[10] The Allen brothers commissioned the 262-ton Constitution to travel to Houston. Captain Edward Auld piloted the large, deep-draft steamer to the wharf at the foot of Main Street, and earned $1,000 for performing this task. However, the Constitution—measuring at 150 feet—was too long to make the three point turn using the mouth of White Oak Bayou. Unable to turn the ship around at Houston, Auld ran the engines in reverse for over six miles until he found a natural turning basin.[11] The Allen brothers published an announcement of the Constitution's feat with the headline, "The Fact Proven."[12]

In May 1837, the Texas Congress met for the first time in Houston. The First Texas Congress had initially convened in Columbia, Texas, but adjourned the first session on December 22, 1836. The First Congress reconvened in Houston to finish its business five months later.[13] Houston was granted incorporation by the Texas legislature on June 5, 1837. At this time, drunkenness, dueling, brawling, prostitution, and profanity began to become a problem in early Houston.[9] Soon, Houstonians were prompted to put an end to their problems; so, they wanted to make a Chamber of Commerce just for the city. A bill had been introduced on November 26, 1838 in Congress that would establish this entity. President Mirabeau B. Lamar signed the act into law on January 28, 1840. This move could not have come sooner, as the city was suffering from financial problems and numerous yellow fever outbreaks, including an 1839 outbreak that killed about 12 percent of its population. Also, on January 14, 1839, the capital had been moved to Austin, known as Waterloo at the time. On April 4, 1840, John Carlos hosted a meeting to establish the Houston Chamber of Commerce at the City Exchange building. E.S. Perkins presided as its first president. In addition to Perkins and Carlos, the charter members admitted were: Henry R. Allen, T. Francis Brewer, Jacob De Cordova, J. Temple Doswell, George Gazley, Dewitt C. Harris, J. Hart, Charles J. Hedenburg, Thomas M. League, Charles Kesler, Charles A. Morris, E. Osborne, and John W. Pitkin. Undergrowth and snags had been the greatest obstacle to navigating Buffalo Bayou; yet by 1840, there was an accumulation of sunken ships. This was the principal concern of the new Houston Chamber of Commerce. The city of Houston and Harris County responded by allocating taxpayer money for bayou clearance, and on March 1, 1841, the first wreck was pulled out the bayou under this program.[14]

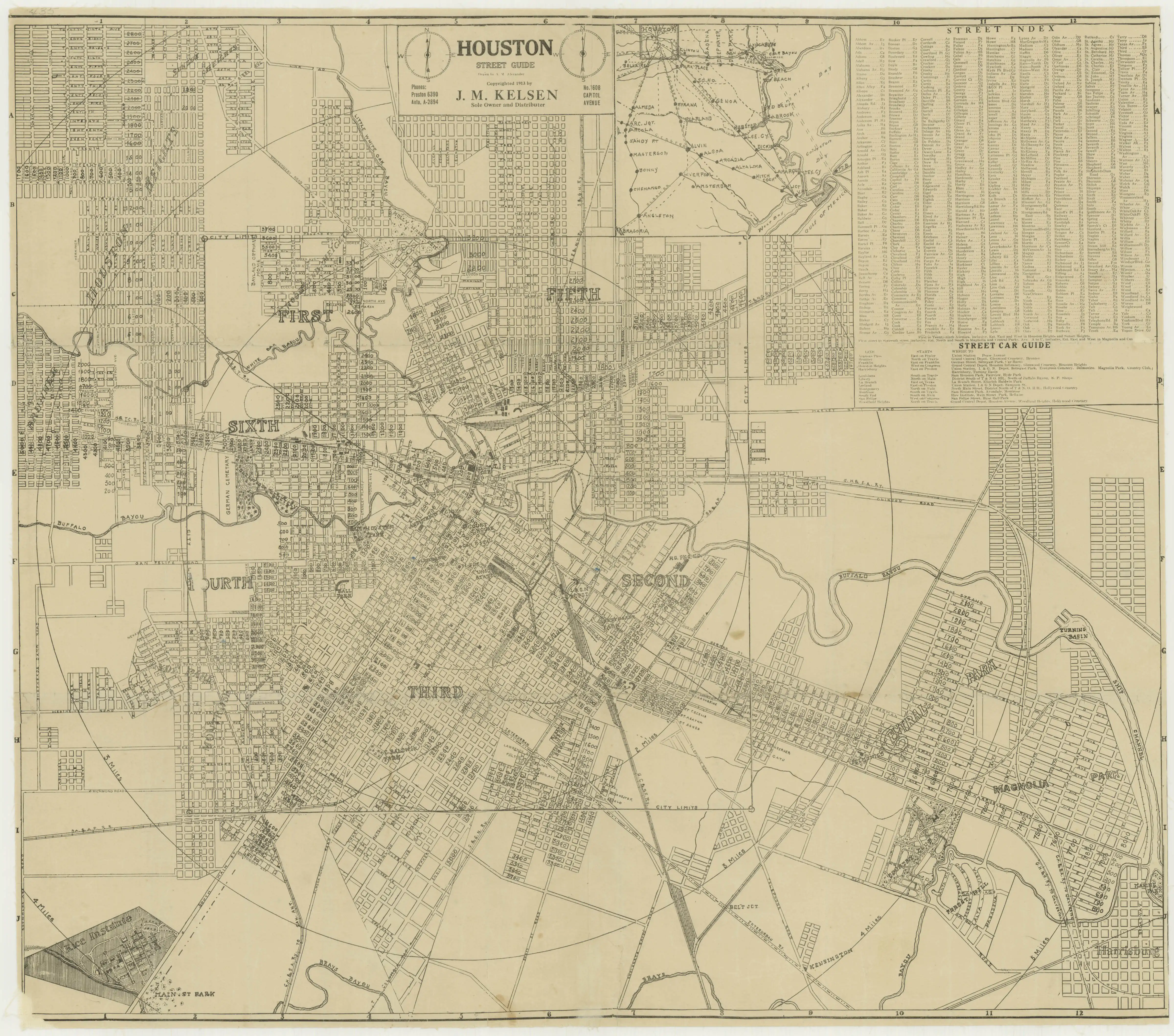

The original municipal government structure was a mayor and eight aldermen, all elected at large. Two charter amendments, one in 1839 and the other in 1840, divided the town into four wards, using Main and Commerce streets as axes. Each ward elected two alderman under this system. The wards are no longer political divisions, but some of the names are still used, even though they do not refer to the original boundaries.[15]

Serious violence was a daily occurrence in the late-1830s. In addition to assault via a gentleman's cane, street violence emanated from Houston's many saloons and brothels. [16] When Mexico was again threatening Texas, President Sam Houston moved the capital to Houston on June 27, 1842. However, the Austin residents wanted to keep the archives in their city. This would be known as the Archive Wars. The capital was then moved to Washington on-the-Brazos on September 29. Austin became capital again in 1845, just before Texas gained statehood.[17]

Early statehood, 1845–1861

In the early statehood era, historian Harold Platt notes the emergence of "commercial-civic elites," a term borrowed from Blaine A. Brownell. Commercial leaders blurred sharp distinctions between economic activity and social relationships. One example was the business partnership of Thomas W. House and Charles Shearn. House started in Houston as a junior partner with the elder Shearn. House married Shearn's daughter while transitioning from his bakery into a cotton mercantile store, and later moving into the banking and real estate businesses. By the mid-1850s, his investment portfolio included transportation concerns, such as plank roads, railroads, and navigation companies. House was a founder of the Shearn Methodist Church and a co-founder of the first volunteer fire company in Houston. In 1857 he was elected as an alderman.[18]

During Houston's first few years, it had many characteristics of a frontier town. Though this trend briefly reversed, the demographics of Houston's free population regressed toward those of a frontier town again during the 1850s. The imbalance in population favoring males increased, the median age was greater than the US at-large, and these males were less likely to be married. The number of young men quadrupled from 1850 to 1860, but the total population merely doubled during the same period. In 1850, Houston had 115 males for every hundred females, and this ratio increased to 136 per hundred by 1860. Saloons and gambling halls proliferated and were well attended, and violence was common. One in three Houstonians were born abroad, many coming from German-speaking countries.[19]:254–258 More than one of every five Houstonians during this period was an enslaved person.[20][21] Though the percentage of bondsmen in Houston was comparable to those of other southern cities, there was a lower proportion of slaveowners. The practice of "hiring out" enslaved persons was common in Houston at the eve of the Civil War. Houston's total population grew to 4,428 by 1860, and its footprint expanded to the southwest by several blocks, reaching to a part of current-day Hadley Street.[22] Urban bondsmen performed manual labor, such as construction, or moving freight at the wharf or to and from the warehouses; others worked as servants at private homes and hotels, or as cooks and waiters.[23]

Railroads started to emanate from Houston in the 1850s. However, the first railroad to operate in Texas was the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railway, which terminated at Harrisburg, Houston's rival to the east. This road began service in 1853.[24] Houston gained access to this railway to the Brazos bottoms in October 1856 through the construction of the Houston Tap Road.[25]:48 Construction on a railroad based in Houston started in 1853. The railroad, which was later known as the Houston and Texas Central Railway (H&TC), was complete to Cypress in 1853.[26] The H&TC progressed beyond Cypress, laying track through Hempstead and Navasota, and reached Millican on the eve of the Civil War. Meanwhile, in 1858, the municipally owned Houston Tap was acquired by a private railroad developer, and served as the basis for the Houston Tap and Brazoria Railway, a road to the sugar plantations, which began service to Columbia in 1860. Another railroad opened during this period, accessing Houston from its initial southern terminus opposite Galveston. The Galveston, Houston and Henderson Railroad completed tracks from Virginia Point to Houston on January 8, 1859. The next year Houston provided railroad access to Galveston when the Island City finished the long viaduct across the back bay. From 1857, the Texas and New Orleans Railroad broke ground north of Buffalo Bayou in 1857 and continued to construct the road into East Texas through 1860.[25]:49–51

The Civil War, 1861–1865

In 1860, most Houstonians supported John C. Breckinridge, the Southern Democratic candidate for president. As the Civil War began, there was tension between supporters of the Confederacy and the few Union sympathizers. There are no voting tallies for Houston and there are inconsistencies in the records of the secession vote, yet, Harris County voted heavily in favor of secession on February 23, 1861 by a margin as high as seven-to-one. The Chamber of Commerce kept the city together during the conflict.[27][28]

Houston was an important regional center during the Confederacy. The town served as a military logistics center, the Quartermaster Depot for Texas, and the headquarters of a wartime administrative district which included Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. An influx of refugees from Louisiana and Galveston nearly doubled Houston's wartime population compared to 1860. Since the town suffered no direct attacks, it was prosperous compared to many other communities in the South. Though some key merchants like William Marsh Rice left at the start of the war, businessmen from New Orleans and Galveston replaced them. Blockade runners sometimes used Houston as a port, and on occasion the Main Street wharf received foreign cargo.[29] Despite disruptions to supply from the Union blockades, advertisements indicate at least occasional availability of staples, such as sugar, coffee, and soap; clothing, including pants, shirts, and footwear; and building supplies, like brick, and even milled pine.[30] However, the supply of goods was not consistent, and there were periodic shortages of some staples, causing hyperflation and the need to find substitute goods, such as flavoring hot drinks with okra seeds in place of coffee. Specie was in short supply throughout the war. Housing scarcity caused rents to rise, but wages increased at the same time.[31]

Post-Civil War, 1866–1900

Reconstruction

_(14783364343).jpg.webp)

The end of the Civil War and news of emancipation spurred an influx of former slaves from the countryside into Houston. The town's incumbent black residents organized groups to help these newcomers obtain housing and employment. In the short term, however, many of these new citizens resided in abandoned buildings and tent communities.[32]

Houston added the Fifth Ward in 1866, and the Sixth Ward in 1877.[15] Each ward was represented by two aldermen, though by 1870, local representation was unequal based on population of the respective wards. The Fourth Ward counted 3,055 residents, contrasted with the First Ward with only 738 residents. The city did not adjust the ward boundaries to compensate for these unequal settlement patterns.[33]

In 1869, the Ship Channel Company was formed to deepen Buffalo Bayou and improve Houston as a shipping port. Despite the postwar social unrest, migrants flocked to Texas for new opportunities. Texas businessmen joined together to expand the railroad network, which contributed to Houston's primacy in the state and the development of Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio and El Paso.[34]

After Texas was readmitted to the Union on April 16, 1870, Houston continued its growth. Houston was designated as an official port of entry on July 16, 1870. Its new charter drew up eight wards. Many freedmen opened businesses and worked for wages under contracts. The Freedmen's Bureau stopped abuse of the contracts in 1870. Many African Americans at the time were in unskilled labor. Many former slaves legalized their marriages after the American Civil War. White legislators insisted on segregated schools. White Democrats regained power in the state legislature in the late 1870s, often after violence and intimidation to suppress African-American voting. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Texas passed a new constitution and laws that effectively disenfranchised most African Americans by making voter registration and voting more complicated and subject to white administration. The Democratic-dominated legislature passed Jim Crow laws to establish and enforce legal segregation across the state.[35]

Houston was the site of the first Texas State Fair in 1870. The Mechanical and Blood Stock Association of Texas convened the first and second state fairs on a temporary site north of Buffalo Bayou. The organization later purchased a more lasting fairground area within the Obedience Smith Survey, in an area more recently known as "Midtown," south of the original Houston survey. They used this new site for the first time in 1872, where new streetcar service conveyed visitors between the fair and central Houston. The last fair State fair in Houston was held in 1878.[36]

Gilded Age

Houston continued its rapid population growth which started in the 1860s. Houston, like many other cities, attracted many Americans seeking job opportunities. In 1870, Houston counted 9,382 residents and grew by rates of 77 percent, 67 percent, and 62 percent in the following three decades. The percentage of foreign-born Houstonians declined from 17 percent in 1870 to 11 percent in 1890, but the percentage of African-American residents held steady.[37]

Houston City Streetway Company (HCSC) began operating construction and operation of animal-powered streetcar lines in 1874. The first streetcar service began in 1868, but these early attempts to establish service in Houston were commercial failures. HCSC developed service in the business district, then centered on Congress Avenue and Main Street, though one the first four lines extended as fair south as the Fairgrounds. Another line offered service on Congress to the International & Great Northern Railroad depot. Suburban subdivisions were developed near the Fairgrounds around the same time, and residential developers used the emerging streetcar lines to promote these new subdivisions. Lots sales in these more remote areas, however, did not sell quickly in the 1870s. An upstart company, the Bayou City Street Railway, built its main line further south on Texas Avenue in 1883. Later the same year, William Sinclair and Henry MacGregor acquired both streetcar companies and consolidated their operations.[38] From 1874 until 1891 all of the transit service was operated using mule-driven streetcars, when electric streetcars began to be implemented in their place.[39]

Lumber became a large part of the port's exports, with merchandise as its chief import. The Houston Post was established in 1880. The Houston Chronicle followed on August 23 of that year. In 1887, the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word established a hospital that would become St. Joseph Hospital.[40]

According to the 1890 US Census, Houston was home to 210 manufacturers hiring over 3,000 employees, about 300 of whom were white-collar workers. These companies included metal working facilities, such as blacksmith shops, iron foundries, and wheelwrights; woodworkers, such as cabinet makers and millworks; and many publishers and printers. Over 1,100 workers were employed by Houston railroads, many of them at the large shops of the Southern Pacific Railroad, the Houston and Texas Central Railroad, and the Houston, East and West Texas Railway. Three years later, there were ten railroads doing business in Houston.[41]

Progressive Era, 1901–1928

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On September 8, the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 savagely tore apart the city of Galveston, Texas. Houston suffered mainly property damage from high winds and four inches of rainfall, though one death was reported. The city mobilized to convey fresh water, food, medical supplies, and clothing to Galveston via steamboat and repaired damaged railroads in order to reestablish service to the island. Survivors fled Galveston to seek temporary shelter in Houston. The 1900 US Census reported that 58,203 people were living in Houston. A year later, wildcatters were digging wells at Spindletop as Houston emerged as a regional petroleum center, the home base of many new oil companies. A few Houstonians were buying the first automobiles in the city, while two local breweries produced and sold more than 200,000 barrels of beer. Two major fires struck the city, destroying the Market House and one of the top hotels in town, Hutchins House. New subdivisions developed along the streetcar lines, mostly toward the south. One new addition to the city was Westmoreland.[42]

Around 1910, large numbers of Mexican immigrants settled in the "Segundo Barrio" (Second Ward), near industrial jobs for railroads and manufacturers of supplies for railroads. The Rusk Settlement House and El Campo Laurel lodge were two Second Ward organizations serving the emerging Mexican community in Houston. The Archdiocese of Galveston dispatched a missionary to the area, and later this initiative evolved into the Lady of Guadalupe Church. Several protestant churches in the area followed. Revolution in Mexico the same year changed the immigration dynamic. In some cases, war induced Mexican-Houstonians to return to their native country to join the fight or assist family, but as the war dragged on, immigration from Mexico to Houston increased, mostly from the northern states of Coahuila, Nuevo León, and San Luis Potosí. Civil unrest in Mexico persisted into the 1920s, promoting continued immigration and the development of a robust Mexican-American community in Houston.[43]

In 1912, Joseph Jay Pastoriza introduced property tax reform to Houston. The "Houston Single Tax Plan" was based on Georgist principles and redistributed property tax burden from owners of personal property and developed land to owners of undeveloped land. While the Houston Plan was not a true single tax, it re-weighted appraisals to 70 percent of unimproved land and 25 percent of developed land. Personal property was exempt from local taxes according to this plan. This continued for a few years until 1915, when two courts ruled the plan illegal according to the Texas Constitution. Pastoriza continued to serve as Houston Tax Commissioner until 1917, when he became the first Mayor of Houston of Hispanic heritage. He died after just three months in office.[44]

In 1912, Houston established its first institution of higher learning. The Rice Institute, now Rice University, opened with an endowment of around $9 million. The board hired Edgar Ovett Lovett as the school's first president, who recruited Julian Huxley as a professor of biology and Harold Wilson as a professor physics.[45]

By 1912, Houston was home to twenty-five "tall buildings" ranging from six to sixteen stories. Office buildings extant in 1912 include the eleven-story Scanlan Building, the marble-clad South Texas National Bank Building, the eight-story First National Bank Building, the twelve-story Union National Bank, the ten-story Houston Chronicle Building, and the Southwestern Telephone Company Building. The sixteen-story Carter Building was the tallest in Houston. There were two major passenger train facilities, Union Station and Grand Central Station. Residential buildings included the Beaconsfield apartments, Rossonian apartments, the Savoy flats, and the Hotel Bender. Under construction in 1912 was the Rice Hotel.[46]

In early 1917 the War Department ordered two military installations to be built in Harris County: Camp Logan and Ellington Field. The Army deployed a battalion of the all-black 24th Infantry Regiment to guard the construction site at Camp Logan. Racial tension in the city rose as the black soldiers received hostile treatment in the racially segregated city. Tensions flared into a full-blown riot in August 1917; the Camp Logan Riot resulted in the deaths of fifteen whites (including four policemen) and four black soldiers, and scores of additional injuries.[47]

_(14580301379).jpg.webp)

During the 1920s, the City of Houston developed Hermann Park based in part on plans by Arthur Comey and George Kessler on land donated by George H. Hermann in 1922. The Houston Zoological Garden opened on the park grounds two years later. The park complex expanded with the construction of Museum of Natural History and a full-size golf course. Several smaller buildings were also added, as well as several curving roads to provide automobile access through the grounds. Will Hogg donated another large tract for an expansion to the park.[48]

Houston hosted the 1928 Democratic National Convention. The city council and Mayor Oscar Holcombe appropriated $100,000 for a new convention hall. They commissioned Kenneth Franzheim and Alfred C. Finn for design and construction management of the new hall. After condemning and demolishing some houses to clear the site, Sam Houston Hall was complete within four months. The city expected 25,000 conventioneers, and the new facility was larger than Madison Square Garden. Houston spent another $100,000 for beautification, mainly with planting of gardens and trees at various public buildings and public parks. With only around 5,000 hotel rooms to lodge visitors, several hotels broke ground. Furthermore, the city organized many improvised accommodations, including campgrounds, makeshift dormitories, and converted railcars.[49]

The Great Depression, 1929–1941

In May 1929, a flood caused millions of damage to Houston property.[50]

Houston's population in 1930 was 292,352. Despite the stock market crash, Houston was still building. The Sterling Building was one of a dozen skyscrapers completed in 1930. Yet unemployment was still high and a cause for concern to Mayor Walter Monteith. Modernization of downtown continued in 1931 as two old buildings were razed: The Hotel Brazos and an old house built in 1841 came down at Louisiana and Prairie.[51] Petroleum dominated the landscape of the Houston Ship Channel, not cotton. More dredging east of Harrisburg and new docks at the Turning Basin added to the port's infrastructure. Several local roads were paved around this time. Air travel expanded as new passenger service began from Houston to Atlanta. Despite this economic activity, signs of the Depression included auction sales of four major downtown buildings. In December 1935, floods struck the city, causing over $1 million in property damage and killed as many as six people. Houston and the State of Texas celebrated their centennials in 1836.[52]

Jesse H. Jones led a group of local bankers in 1931 to pool their resources in order to save the weaker banks. This was not enough to prevent the worst part of the Great Depression in 1932 and early 1933, when building activity in the private sector decreased. Federal funding from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the Works Progress Administration facilitated major construction projects in the mid-1930s, including assistance for a new Houston City Hall and Lamar High School. Houston International Airport expanded commercial and passenger facilities during the 1930s, while Braniff, Eastern, and Southern airlines all offered regular service by 1941.[53]

World War II, 1941–1945

When World War II started, tonnage levels fell at the port and five shipping lines ended service. April 1940 saw streetcar service replaced by buses. Robertson Stadium, then known as Houston Public School Stadium, was erected from March 1941 to September 1942. Also that year, Pan Am started air service. World War II sparked the reopening of Ellington Field. The Cruiser Houston was named after the city. It sank after a vicious battle in Java, Indonesia in 1942. August 1942 also saw the new City Manager government enacted. The M. D. Anderson Foundation formed the Texas Medical Center in 1945. That same year, the University of Houston separated from HISD and became a private university. Aircraft and shipbuilding became large industries in Texas as a result of the war. Tonnage rose after the end of the war in 1946. During the same year, E. W. Bertner gave away 161 acres (0.65 km²) of land for the Texas Medical Center. Suburban Houston came to be in the period from 1946 to 1950. When Oscar F. Holcombe took his eighth term in 1946, he abandoned a city manager type of government. Foley's department store opened in 1947. The Alley Theatre got its first performance in 1947. Also the same year, voters overwhelmingly rejected a referendum for citywide land-use districts--zoning. The banking industry also rose to prominence in the late 1940s. Houston carried out a large annexation campaign to increase its size. When air conditioning came to the city, it was called the "World's Most Air Conditioned City". The economy of Houston reverted to a healthy, port driven economy.

1950s

Texas Medical Center became operational in the 1950s. The Galveston Freeway and the International Terminal at Houston International Airport (nowadays Hobby Airport) were signs of increasing wealth in the area. Millions of dollars were spent replacing aging infrastructure. In 1951, the Texas Children's Hospital and the Shriner's Hospital were built. Existing hospitals had expansions being completed. July 1, 1952 was the date of Houston's first network television. Later on that same year, the University of Houston celebrated its 25th anniversary. Another problem Houston had back in the 1950s was the fact that it needed a new water supply. They at first relied on ground water, but that caused land subsidence. They had proposals in the Texas Congress to use the Trinity river. Hattie Mae White was elected to the school board in 1959. She was the first African-American to be elected in a major position in Houston in the 20th Century. Starting in 1950, Japanese-Americans as a whole were leaving horticulture and going into business in larger cities, such as Houston.

1960s

In the year 1960, Houston International Airport was deemed inadequate for the needs of the city. This airport could not be expanded, so Houston Intercontinental Airport (now George Bush Intercontinental Airport) was built north of the city. September 1961 saw Hurricane Carla, a very destructive hurricane, hit the city. On July 4, 1962, NASA opened the Manned Spacecraft Center in southeast Houston in the Clear Lake area, now the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. This would bring many jobs to the Houston, especially the Clear Lake area. Also in 1962, Houston voters soundly defeated a referendum to implement zoning—the second time in fifteen years. In 1963, the University of Houston ended its status as a private institution and became a state university by entering into the Texas State System of Higher Education after a long battle with opponents from other state universities blocking the change.

In April 1965 the Astrodome opened, under the name of the Harris County Domed Stadium. In July 1965, the Houston Metropolitan Area was expanded by the inclusion of Brazoria County, Fort Bend County, Liberty County, and Montgomery County. AstroWorld, a theme park adjacent to the Astrodome, opened in 1968. Houston Intercontinental Airport was built in 1969. Houston International Airport, renamed to Hobby Airport, was closed to commercial aviation until 1971.

Barbara Jordan was elected to the US House of Representatives by Houston residents on November 8, 1966.

1970s and integration

In the 1970s, the Chinese-American community in Houston, which had been relatively small, started growing at a rapid rate.

The Sharpstown scandal, which concerned government bribes involving real estate developer Frank Sharp (neighborhood of Sharpstown is named after him) occurred in 1970 and 1971.

One Shell Plaza and Two Shell Plaza were completed in 1971. One Shell Plaza was the tallest building west of the Mississippi River.

Because the Houston Independent School District was slow to desegregate public schools, on June 1, 1970, the Federal officials struck the HISD plan down and forced it to adopt zoning laws. This was 16 years after the landmark Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, which determined that segregated schools were inherently unequal. Racial tensions over integration of the schools continued. Some Hispanic Americans felt they were being discriminated against when they were being put with only African-Americans as part of the desegregation plan, so many took their children out of the schools and put them in huelgas, or protest schools, until a ruling in 1973 satisfied their demands.

The Third Ward became the center for the African-American community in the city. By 1979 African Americans were elected to the City Council for the first time since Reconstruction. During the time period, five African Americans served on city council.

Water pollution of the Houston Ship Channel became notorious in 1972. Work on the Texas Commerce Tower, now the JPMorgan Chase Tower, began in 1979.

The late 1970s saw a population boom thanks to the Arab Oil Embargo. People from the Rust Belt states moved into Houston, at a rate of over 1,000 a week, mostly from Michigan, and are still moving to Houston to this day.

The city made changes in higher education. The Houston Community College system was established in 1972 by HISD. In 1977, the University of Houston celebrated its 50th anniversary as the Texas Legislature established the University of Houston System—a state system of higher education that includes and governs four universities. In 1976, Howard Hughes, at one time the world's richest man, died on his jet heading to Houston. He was born in Humble, Texas, the home of what is now ExxonMobil.

1980s

In 1981, Kathryn J. Whitmire became the city's first female mayor, holding that position for 10 years; after she left office, term limits were enacted to prevent future mayors from serving for more than 6 years.[54] Several new construction projects, including The Park Shopping Mall, the Allied Bank Tower, the Gulf Tower and several other buildings were being carried out in downtown. The Transco Tower, the tallest building in the world outside of a central business district, was completed in 1983. METRO wanted to build a rail system connecting the city with the suburbs, but the plan was rejected by voters on June 11, 1983. Voters did, however, approve plans for the George R. Brown Convention Center. In August 1983, the University of Houston changed its name to "University of Houston–University Park" in order to separate its identity from other universities in the University of Houston System; however, the name was reverted to University of Houston in 1991.[55][56][57] On August 18, 1983, Hurricane Alicia struck Galveston and Houston, causing $2 billion in damage.[58] Houston's massive population boom was reversed when oil prices fell in 1986, leading to several years of recession for the Houston economy. The space industry also took a blow that year with the Challenger disaster in Florida. The first nine months of 1987 saw the closure of eleven banks, but also the opening of several cultural centers including the George R. Brown Convention Center, the Wortham Theatre, and the Menil Collection. On August 7, 1988, Congressman Mickey Leland died in a plane crash in Ethiopia. On October 3, a Phillips 66 plant exploded in adjacent Pasadena, killing 23 and injuring 130 people. The Houston Zoo began charging admission fees for the first time in 1988.

1990s

1990 saw the opening of Houston Intercontinental Airport's new 12-gate Mickey Leland International Airlines terminal, named after the recently deceased Houston congressman. In 1991 Sakowitz stores shut down; the Sakowitz brothers had brought their original store from Galveston to Houston in 1911. August 10, 1991 saw a redrawing of districts for city council, so that minority groups could be better represented in the city council. 1993 saw the G8 visiting to discuss world issues, and zoning was defeated for a third time by voters in November.

The master-planned community of Kingwood was forcibly annexed in 1996, angering many of its residents.[59] The annexation put Kingwood in the jurisdiction of Houston's fire and police services, but it did not alter school district boundaries nor did it change postal addresses and postal services.[60]

Rod Paige became superintendent of Houston Independent School District in 1994; during his seven-year tenure the district became very well known for high test scores, and in 2001 Paige was asked to become Secretary of Education for the new George W. Bush administration. Lee P. Brown, Houston's first African-American mayor, was elected in 1997.

Twenty-First Century

The city's major sports teams were using outdated stadiums and threatened to leave. Eventually, in 1996, the Houston Oilers did so after several threats. The city built Enron Field (now Minute Maid Park) for the Houston Astros. Reliant Stadium, now NRG Stadium, was erected for the NFL expansion team Houston Texans.

Tropical Storm Allison devastated many neighborhoods as well as interrupted all services within the Texas medical center for several months with flooding in June 2001. At least 17 people were killed around the Houston area when the rainfall from Allison that fell on June 8 and 9 caused the city's bayous to rise over their banks.[61]

In October 2001 Enron, a Houston-based energy company, got caught in accounting scandals, ultimately leading to collapse of the company and its accounting firm Arthur Andersen, and the arrest and imprisonment of several executives.

In 2002, the University of Houston celebrated its 75th anniversary with an enrollment of 34,443 that fall semester. At the same time, the University of Houston System celebrated its 25th anniversary with a total enrollment of over 54,000.

The new international Terminal E at George Bush Intercontinental Airport opened with 30 gates in 2003.

The Toyota Center, the arena for the Houston Rockets opened in fall 2003.

METRO put in light rail service on January 1, 2004. Voters have decided by a close margin (52% Yes to 48% No) that METRO's light rail shall be expanded.

In 2004, the Mayor of the city was Bill White and Houston unveiled the first Mahatma Gandhi statue in the state of Texas at Hermann Park. Houston's Indian American Community were cheerful after 10 years, in 2010, when the Hillcroft and Harwin area were renamed Mahatma Gandhi District in honor of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi as that area is the center of Indian commerce.[62]

In the aftermath of the Hurricane Katrina disaster, about 200,000 New Orleans residents resettled in Houston. Soon following Katrina was Hurricane Rita, a category 5 hurricane which caused 2.5 million Houstonians to evacuate the city, the largest urban evacuation in the history of the U.S.

Six Flags AstroWorld, Houston's only large theme park, closed in 2005.

By 2008, the widening of I-10 was taking place, and eventually incorporated toll lanes. Also, Discovery Green park was created.

In January 2010, Annise Parker became the first openly gay mayor of a large American city upon her inauguration as Houston's mayor.

Memorial Day storms in 2015 brought flash flooding to the city as some areas received 11 inches or more of rain overnight, exacerbated by already full bayous. At least three people died and more than 1,000 cars were stranded on highways and overpasses.[63]

In April 2016, historic flooding came to Houston which has killed 5 people.[64]

In August 2017, Houston experienced record flooding as a result of Hurricane Harvey. The damages due to flash flooding are estimated at or above $50 billion, making it one of the worst and costliest natural disasters in the United States. Relief efforts are currently underway and are expected to last for years to come.

See also

- Allen Ranch, occupied much of modern Houston and was an early driver of city's growth

- History of the Mexican-Americans in Houston

- List of mayors of Houston

- Timeline of Houston

Citations

- Handbook of Texas Online, Carol A. Lipscomb, "Karankawa Indians," accessed May 28, 2020.

- Handbook of Texas Online, Dorothy Couser, "Atakapa Indians," accessed May 28, 2020.

- "Austin, John". Texas Handbook Online. Texas State Historical Association. September 2, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- McComb (1981), pp. 11–14.

- McComb (1981), pp. 8–11.

- Joe B. Frantz (1951). "Moses Lapham: His Life and Some Selected Correspondence, I". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 54 (3): 324–332. JSTOR 30237584.

- Winkler, Ernest William (October 1906). "The Seat of Government of Texas. I. Temporary Location of the Seat of Government". The Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association. 10 (2): 165–170. JSTOR 30242920.

- Kleiner, D.J. (August 26, 2016). "Allen's Landing". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- McComb, David G. (February 15, 2017). "Houston, TX". Texas Handbook Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Sibley (1968), pp. 37–39.

- Hall (2012), pp. 34–36.

- Sibley (1968), p. 38.

- Kemp (1944), pp. 3–4.

- Sibley (1968), pp. 46–50.

- Chapman, Betty Trapp (2011). "A System of Government Where Business Ruled" (PDF). Houston Review. 8 (1): 29–33. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- Hogan (1946), pp. 270–272.

- Humphrey, David G. (May 1, 2017). "Austin, TX (Travis County)". Texas Handbook Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Platt (1983), pp. 8–9.

- Jackson, Susan (January 1978). "Movin' On: Mobility through Houston in the 1850s". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 81 (3): 251–282. JSTOR 30236841.

- Jackson, Susan (Summer 1980). "Slavery in Houston: The 1850s". Houston Review. 2 (2): 66–81.

- Beeth and Wintz (1992), p. 15.

- Levengood (April 1998), pp. 403–404.

- Beech and Wiltz (1992), pp. 14–15.

- Werner, George C. (June 12, 2010). "Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railway". Texas Handbook Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Muir, Andrew Forest (July 1960). "Railroads Come to Houston 1857–1861". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 64 (1): 42–63. JSTOR 30240901.

- Werner, George C. (March 20, 2017). "Houston and Texas Central Railway". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Joe T. Timmons, "The Referendum in Texas on the Ordinance of Secession, February 23, 1861: The Vote." East Texas Historical Journal 11.2 (1973) p. 15 online.

- Andrew F. Lang, "Memory, the Texas Revolution, and Secession: The Birth of Confederate Nationalism in the Lone Star State." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 114.1 (2010): 21-36.

- Levengood (April 1998), pp. 404–408.

- Levengood (April 1998), pp. 414–415.

- McComb (1981), pp. 52–53.

- Beech and Wintz (1992), pp. 21–22.

- Ziegler (May 1872), pp. 12–13 (.pdf 15–16).

- Marion Merseburger, "A political history of Houston, Texas, during the reconstruction period as recorded by the press: 1868-1873" (PhD Dissertation,. Rice U. 1950; online.

- Barry A. Crouch and Larry Madaras, The Dance of Freedom: Texas African Americans During Reconstruction (U of Texas Press, 2007).

- Meeks, Flori (March 28, 2013). "Few traces remain of state fair site". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- Ziegler (May 1972), pp. 8–10 (.pdf 11–13).

- Baron (1994), pp. 68–69.

- Poor, Henry Varnum (1892). Poor's Directory of Railway Officials. New York City: Poor's Publishing Company. p. 364.

- "St Joseph Medical Center | Houston, TX". Sjmctx.com. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- Ziegler (May 1972), pp. 4–5 (.pdf 7–8).

- Carroll (1912), pp. 103–105.

- Rosales, F. Arturo (Summer 1981). "Mexicans in Houston: The Struggle to Survive, 1908—1975" (PDF). The Houston Review: 224–248.

- Davis, Stephen (1986). "Joseph Jay Pastoriza and the Single Tax in Houston, 1911–1917" (PDF). 8 (2). Houston Review: history and culture of the Gulf Coast.

- Boles, John B. "Rice University". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- Carroll, Jr., B.H. (1912). "23". Standard History of Houston Texas From a study of the Original Sources. Knoxville, Tennessee: H.W. Crew and Company. Retrieved December 27, 2014. Courtesy of the Woodson Research Center at Rice University.

- Haynes, Robert V. (June 15, 2010). "Houston Riot of 1917". Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- Fox, Stephen (Spring 1983). "Big Park, Little Plans: A History of Hermann Park" (PDF). Cite Magazine. 3: 18–21.

- Fenberg (2011), pp. 140–142.

- WPA Writers (1946), p. 117.

- WPA Writers (1946), p. 117.

- WPA Writers (1946), pp. 119–121.

- McComb (1981), pp. 115–117.

- Keeping the momentum going on the rail project. Kristen Mack, Houston Chronicle. August 17, 2006. Last accessed October 20, 2006.

- Adair, Wendy (2001). The University of Houston: Our Time: Celebrating 75 Years of Learning and Leading. Donning Company Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57864-143-7.

- "72(R) History for Senate Bill 755". Texas Legislature Online History. Texas Legislature. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- "72(R) History for House Bill 2299". Texas Legislature Online History. Texas Legislature. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- Costliest U.S. Hurricanes 1900-2004 (unadjusted). National Hurricane Center, National Weather Service. Last accessed November 19, 2006.

- Lee, Renée C. (October 8, 2008). "Annexed Kingwood split on effects". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- "City of Houston Annexation FAQ". City of Houston. 1996-10-31. Archived from the original on 1996-10-31. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- Hegstrom, E., & Christian, C., "17 deaths attributed to storm," Tropical Storm Allison (Houston Chronicle, June 11, 2001).

- Moreno, Jenalia. "Signs of identity South Asian community is planning a celebration today to mark the creation of a district named for Mahatma Gandhi." Houston Chronicle. January 16, 2010. Retrieved on July 27, 2010.

- Katz, Rachel & Good, Dan., "Houston Flooding: 3 People Dead As Still More Rain Expected" (ABC News, May 26, 2015).

- "CNN". CNN.

References

- Baron, Steven M. (1994). "Streetcars and the Growth of Houston" (PDF). The Houston Review. 16 (2): 67–100. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- Beeth, Howard; Wintz, Cary D., eds. (1992). Black Dixie: Afro-Texan History and Culture in Houston. College Station: Texas A & M University Press.

- Carroll, B. H., Jr. (1912). Standard History of Houston Texas From a study of the Original Sources. Knoxville, Tennessee: H. W. Crew and Company. p. 23. Retrieved December 27, 2014. Digital reproduction from the Woodson Research Center at Rice University.

- Davis, Stephen (1986). "Joseph Jay Pastoriza and the Single Tax in Houston, 1911–1917" (PDF). 8 (2). The Houston Review: 56–78. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hall, Andrew P. (2012). Galveston-Houston Packet: The Steamboats on Buffalo Bayou. Charleston, SC: The History Press. ISBN 978-1609495916.

- Hogan, William Ransom (1946). The Texas Republic: A Social and Economic History. Austin: Texas State Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-87611-220-5.

- Jackson, Susan (January 1978). "Movin' On: Mobility through Houston in the 1850s". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 81 (3): 251–282. JSTOR 30236841.

- Jackson, Susan (Summer 1980). "Slavery in Houston: The 1850s". Houston Review. 2 (2): 66–81.

- Kemp, L. W. (July 1944). "The Capitol (?) at Columbia". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 48 (1): 3–9. JSTOR 30236053.

- Levengood, Paul Alejandro (1999). "For the duration and beyond: World War II and the creation of modern Houston, Texas". Rice University (PhD dissertation). hdl:1911/19400. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- Levengood, Paul A. (April 1998). "In the Absence of Scarcity: The Civil War Prosperity of Houston, Texas". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 101 (4): 401–426. JSTOR 30239127.

- Maher, Edward R., Jr. (April 1952). "Sam Houston and Secession". Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 55 (4): 448–458. JSTOR 30237605.

- McComb, David G. (1981). Houston: A History. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73020-9.

- Muir, Andrew Forest (July 1960). "Railroads Come to Houston 1857–1861". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 64 (1): 42–63. JSTOR 30240901.

- Platt, Harold L. (1983). City Building in the New South: The Growth of Public Services in Houston, Texas, 1830-1915. Temple University Press.

- Sibley, Marilyn McAdams (1968). The Port of Houston: A History. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- WPA Writers Group (1946). Houston: A History and Guide. Houston: Anson Jones Press.

- Ziegler, Robert E. (May 1972). "The Workingman in Houston, Texas, 1865–1914". Texas Tech University (PhD dissertation). Retrieved March 13, 2020.

Further reading

- Allen, O. F. (1936). "The City of Houston from Wilderness to Wonder". Temple, Texas. - Hosted at the University of North Texas

- Dietzel, Charles, et al. "Diffusion and coalescence of the Houston Metropolitan Area: evidence supporting a new urban theory." Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 32.2 (2005): 231-246. online

- Goldfield, David, ed. (2007). "Houston, Texas". Encyclopedia of American Urban History. Sage. ISBN 978-1-4522-6553-7.

- McCleskey, Clifton, and Dan Nimmo. "Differences between potential, registered and actual voters: The Houston metropolitan area in 1964." Social Science Quarterly (1968): 103-114. online

- McIntosh, Molly Fifer. "Measuring the labor market impacts of Hurricane Katrina migration: Evidence from Houston, Texas." American Economic Review 98.2 (2008): 54-57. online

- Nimmo, Dan, and Clifton McCleskey. "Impact of the poll tax on voter participation: The Houston metropolitan area in 1966." Journal of Politics 31.3 (1969): 682-699. online

- Ponton, David III (2017-03-03). "Criminalizing Space: Ideological and Institutional Productions of Race, Gender, and State-sanctioned Violence in Houston, 1948-1967" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - PhD thesis published by Rice University

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Houston. |

- Houston, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- 174 Years of Historic Houston a Chronology of Houston From 1836 to Present Day

- The Oral History of Houston

- A thumb-nail history of the city of Houston, Texas, from its founding in 1836 to the year 1912, published 1912, hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- True stories of old Houston and Houstonians: historical and personal sketches / by S. O. Young., published 1913, hosted by the Portal to Texas History