Revolt of Saint Titus

The Revolt of Saint Titus (Greek: Eπανάσταση του Αγίου Τίτου) was a fourteenth-century rebellion against the Republic of Venice in the Venetian colony of Crete. The rebels overthrew the official Venetian authorities and attempted to create an independent state, declaring Crete a republic under the protection of Saint Titus (Άγιος Τίτος): the "Republic of Saint Titus".

| Revolt of Saint Titus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

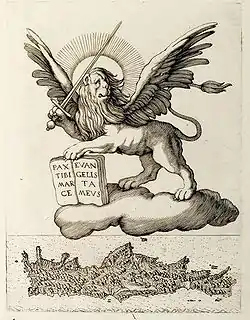

The winged Lion of Saint Mark, symbol of the Venetian Republic, standing guard over the Regno di Candia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Latin feudatories allied with the Greek population | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Marco Gradenigo, Tito Venier, John Callergi | ||||||

Crete under Venice

Crete had been under Venetian rule since 1211, having been sold to Venice by Boniface of Montferrat at the time of the Fourth Crusade. Owing to its central location along the trade routes, its size and its products, Crete had a strategic importance for the Venetian rule in the Eastern Mediterranean.[1] Occupied Crete was divided into fiefs and a colony known as the "Kingdom of Candia" (Italian: Regno di Candia) had been established, having as capital the city of Candia (present-day Heraklion). The land was distributed to Venetian colonists (both nobles and citizens) on the condition that they paid taxes, manned Venetian warships and defended the possession in the name of the motherland. The Venetians ruled Crete primarily for their own interest, driving Cretans to forced labour or conscripting them for the wars of the Republic.[2] Since 1207 and including that of Saint Titus, Crete saw fourteen rebellions against Venetian rule. Saint Titus rebellion was the first in which the Latin colonists were actively involved.

The revolt

Venice demanded its colonies make large contributions to its food supply and the maintenance of its large fleets. On 8 August 1363, Latin feudatories in Candia were informed that a new tax, aimed to support the maintenance of the city's port, was to be imposed on them by the Venetian Senate. As the tax was viewed more beneficial to the Venetian merchants rather than to the land owners, there was strong objection among the feudatories. The news quickly reached the ears of Leonardo Dandolo, the duke of Candia (the colony's governor). After being informed about the feudatories' attitude, Dandolo summoned before him twenty of them and insisted that they conform to the Senate's order. Later in the day, around seventy of the feudatories gathered in the church of St. Titus, the island's patron saint. They decided to send three representatives to the duke, asking that the tax be suspended until a delegation had appealed to Doge Lorenzo Celsi and the Senate in Venice. Dandolo, however, refused to negotiate and ordered the new tax to be proclaimed to the assembled feudatories, asking them to consent on penalty of death and confiscation of property.

The following day, disobedient feudatories stormed the ducal palace and arrested Dandolo and his counselors. Within a week, the revolt spread to the rest of the island and the commanders (rectors) of the main cities were substituted by men loyal to the insurgents. Marco Gradenigo the Elder (Greek: Μάρκος Γραδόνικος) was appointed governor and rector of the whole island. The figure of St. Titus was selected as the emblem of the newly established Commune of Crete. Greeks were admitted to the Grand Council and the Council of Feudatories, and restrictions concerning the ordination of Greek priests were abolished.[3]

The revolt of St. Titus was not the first attempt to dispute the Venetian dominion in Crete. Riots fomented by Greek nobles trying to regain their past privileges were frequent, but these did not have the character of a "national" uprising. However, the revolt of 1363 was unique in that it was initiated by the colonists themselves, who later allied with the Greeks of the island. Being a state colony, Crete featured a fiscal administration imposed over both the Latin and the indigenous population, thus creating the potential of a sympathy and later an alliance between the colonists and those being colonized. This was emphasized further by the fact that at the time of the revolt, settlers had been living in Crete for two or three generations and an acculturation process had made the local culture more familiar to them than that of their homeland Venice.[3]

Venetian reaction

News about the revolt reached Venice in early September. Crete being one of its major overseas possessions, the Senate considered the revolt to be a serious threat to its security, comparable to that posed by Genoa, its traditional enemy. Such was the concern on the issue that the authority for dealing with it passed from the Senate to the more powerful College. The first reaction of Venice was to attempt a reconciliation and send a delegation to Candia, expressing the hope that the colonists would again become faithful to the Republic of Venice.

After the failure of this attempt, Venice proceeded to organize an army to suppress the revolt. Requests for help were sent to Pope Urban V, the doge of Genoa, Joan I of Naples, Peter I of Cyprus, Louis I of Hungary, John V Palaeologus and the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller in Rhodes.[4] Most responded positively, expressing their support and issuing decrees that instructed their subjects to refrain from making any contact or providing any aid to the insurgents on Crete. The Venetian government assigned the leadership of the army it was assembling to the Veronese condottiero Luchino dal Verme.[5]

In anticipation of the Venetian army, the insurgents had begun to argue on the best way to proceed. Eventually, they settled for sending a delegation to Genoa, asking for assistance and offering it control of Crete. However, the Genoese kept their promise of neutrality and refused to intervene, forcing the delegation to depart Genoa empty-handed. The Venetian expeditionary fleet sailed from Venice on April 10, carrying foot soldiers, cavalry, mine sapper, and siege engineers.[5] On 7 May 1364, and before the delegation to Genoa had returned to Candia, the Venetian forces invaded Crete, landing on the beach of Palaiokastro. Anchoring the fleet in Fraskia, they marched east towards Candia and, facing little resistance, they succeeded in re-capturing the city on May 10. Marco Gradenigo the Elder and two of his counselors were executed, while most of the rebel leaders fled to the mountains. Having secured Candia, Venetian forces took punitive actions to discourage a future revolt. Rewards for the capture of the fugitive insurgents were announced, those having participated in the revolt were banished from living in any Venetian territory and their properties were confiscated.

News of the victory reached Venice in June 1364 and was greeted with prolonged celebrations in the Piazza San Marco, which as poet Petrarch described in a letter, included mock battles, banquets, games, races and jousts.[2] After the revolt, a new official, the Capitaneus, was appointed in Crete with the duty of protecting the Venetian dominion against any internal or foreign enemy.

Rebellion of the Callergis

The recapture of the principal cities did not signal the pacification of Crete. Despite the fact that the Latin leadership of the revolt had fallen apart, several feudatories were still hiding in the mountains and a significant portion of the Greek nobility, supported by Greek peasants, continued to harass the Venetian forces and settlers. The strongest resistance was instigated by the Greek Callergis noble family, who resided in the western part of the island. They carried the insignia of the Byzantine Emperor of Constantinople and proclaimed that their struggle was for the Orthodox faith and for freedom from Latin rule. Soon, the entire western part of Crete was in the hands of the insurgents, forcing the Venetian authorities to mount yet another major campaign against them.

At the Doge's request, the Pope declared the war against the insurgents a crusade, promising remission of sins to those offering to fight in or support the war in Crete. The insurgents however managed to extend their domination further east, gaining control of most of the countryside. Eventually, it was only in 1368 and after several attempts that the resistance was shattered and the Venetian rule was consolidated over the entire island.[3]

References

- Jacoby, David (2014). "The Economy of Latin Greece". A Companion to Latin Greece. Brill. pp. 185–216. ISBN 9789004284104.

- Morris, Jan (1990). The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140119947.

- McKee, Sally (December 1994), "The Revolt of St Tito in fourteenth-century Venetian Crete: A reassessment", Mediterranean Historical Review, 9 (2): 173–204, doi:10.1080/09518969408569670

- Setton, Kenneth (1976). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571, Vol. 1: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. American Philosophical Society. pp. 249–257. ISBN 978-0-87169-114-9.

- Crowley, Roger (2013). City of Fortune: How Venice Ruled the Seas. Random House. ISBN 978-0812980226.