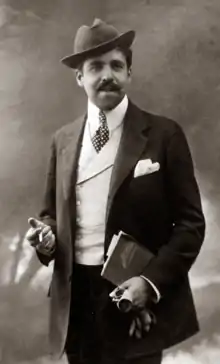

Reynaldo Hahn

Reynaldo Hahn (Spanish pronunciation: [ʁɛ.nal.do ha:n]; 9 August 1874 – 28 January 1947) was a Venezuelan-born French composer, conductor, music critic, and singer. He is best known for his songs – mélodies – of which he wrote more than 100.

Hahn was born in Caracas but his family moved to Paris when he was a child, and he lived most of his life there. Following the success of his song "Si mes vers avaient des ailes" (If my verses had wings), written when he was aged 14, he became a prominent member of fin de siècle French society. Among his closest friends were Sarah Bernhardt and Marcel Proust. After the First World War, in which he served in the army, Hahn adapted to new musical and theatrical trends and enjoyed successes with his first opérette, Ciboulette (1923) and a collaboration with Sacha Guitry, the musical comedy Mozart (1926). During the Second World War Hahn, who was of Jewish descent, took refuge in Monaco, returning to Paris in 1945 where he was appointed director of the Opéra. He died in Paris in 1947, aged 72.

Hahn was a prolific composer. His vocal works include secular and sacred pieces, lyric scenes, cantatas, oratorios, operas, comic operas, and operettas. Orchestral works include concertos ballets, tone poems, incidental music for plays and films. He wrote a range of chamber music, and piano works. He sang as well as played his own songs, and made recordings as a soloist and accompanying other performers. After his death his music was neglected but from the late 20th century onward increasing interest has led to frequent performances of many of his works and recordings of all his songs and piano work, much of his orchestral music and some of his stage works.

Life and career

Early years

Hahn was born in Caracas, Venezuela, on 9 August 1874, the youngest child of Carlos (né Karl) Hahn (1822–1897) and his wife Elena María née de Echenagucia (1831–1912).[1] Carlos Hahn, the eldest son of a Jewish family in Hamburg, emigrated to Venezuela in 1845 at the age of twenty-two, making a highly successful business career there.[2] He converted to Roman Catholicism to marry Elena de Echenagucia; she was of Spanish descent on her father's side and Dutch-English on her mother's.[2] When his friend and associate Antonio Guzmán Blanco became president of the country in 1877, Carlos became Blanco's financial adviser.[2] The Hahns had eleven or twelve children, nine of whom lived to adulthood. Reynaldo, known as "Nano", was the youngest, twenty years younger than his eldest brother.[1] He was brought up speaking fluent German, Spanish and (having a British nanny) English.[3]

When Blanco's first term of office came to an end in 1877, the Hahn family left Venezuela and settled in Paris, where they had relations and well-connected friends.[2] It was France that, as a 21st-century writer put it, would "determine and define Hahn's musical identity in later life".[4] Among the family's Parisian friends was Princess Mathilde, niece of Napoleon I; the young Hahn sang for her, and made his public debut at the age of six, at a musical soirée in her drawing room.[5] He began composition lessons with an Italian teacher when he was eight.[6]

In 1885, aged eleven, Hahn was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire's preparatory course.[6] He went on to study piano with Émile Decombes (in the same class as Maurice Ravel and Alfred Cortot), harmony with Albert Lavignac and Théodore Dubois, and composition with Charles Gounod and Jules Massenet.[5][7] The last became Hahn's lifelong friend and mentor.[8] As a young man Massenet had won France's top musical scholarship, the Prix de Rome,[9] but Hahn could not emulate him: only French nationals were eligible, and the Hahns had not taken French citizenship. Besides, Massenet counselled, with rich parents Hahn did not need the scholarship as his less affluent colleagues did.[10] Through Massenet, Hahn met Camille Saint-Saëns, with whom he studied privately in addition to his Conservatoire lessons.[11]

While still a student Hahn had an early success with his mélodie "Si mes vers avaient des ailes" (If my verses had wings) to a poem by Victor Hugo. The song was among a set of Hahn's mélodies published by the leading music publisher Hartmann et Cie in 1890. Le Figaro took it up – "We feel we must reproduce this graceful piece which obviously denotes a delicate and original musician" – and devoted half a broadsheet page to printing the words and music.[12]

Hahn dedicated "Si mes vers avaient des ailes" to his sister Maria, who had married the painter Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta. At their house Hahn met many of the leading figures in the arts, including Alphonse Daudet, for whose play L'obstacle the teenaged Hahn composed incidental music.[13] The play was presented at the Théâtre du Gymnase on December 1890.[14] Daudet called Hahn's music his "chère musique preferée". At the Daudets' house in 1893 the singer Sybil Sanderson premiered Hahn's Chansons grises, settings of poems by Paul Verlaine. The poet was present and was moved to tears by Hahn's settings of his verse.[15] Stéphane Mallarmé was also present, and wrote:

Le pleur qui chante au langage

Du poète, Reynaldo

Hahn tendrement le dégage

Comme en l'allée un jet d'eau.[16]

The weeping that sings in the words

Of the poet, Reynaldo

Hahn tenderly releases it

Like a fountain on the pathway.

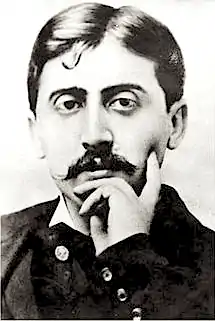

In the early 1890s Hahn worked on his first opera L'île du rêve, a "a Polynesian idyll", written at Massenet's behest. During this period he met Marcel Proust for the first time, at Madeleine Lemaire's salon on 22 May 1894. As far as is known, the 19-year-old Hahn's romantic attachments before then had been intimate but platonic relationships with the famous Parisienne beauties Cléo de Mérode and Liane de Pougy.[5][7] Until this point, he had been uneasy to the point of hostility about homosexuality and homosexuals,[17] but the two men quickly began an intense love affair, Proust's only real liaison.[5] Their affair lasted for little more than two years, but it evolved into a lifetime's close friendship.[18] Proust wrote, "Everything I have ever done has always been thanks to Reynaldo".[19] The music scholar James Harding notes, "It was Hahn who suggested to Proust the famous petite phrase which recurs symbolically throughout À la recherche du temps perdu and which is none other than a haunting theme from Saint-Saëns's D minor violin sonata".[20]

Hahn completed his studies at the Conservatoire satisfactorily but "without producing sparks in examinations and competitions", as his biographer Jacques Depaulis puts it.[3] Massenet resigned from the faculty in May 1896,[21] and Hahn left at the same time as his mentor.[22]

1896 to 1913

In 1896 Proust wrote the words and Hahn the music for Portraits de peintres for reciter and piano, premiered at the house of Madeleine Lemaire, where they had met.[23] Later in that year Hahn formed another of his closest friendships: he had long admired the actress Sarah Bernhardt,[24] and at the end of 1896 he met her and quickly became part of her inner circle of friends and helpers. He frequently visited her in her dressing room during and after performances, lunched with her at her Paris townhouse, travelled with her to London and on tour, and composed music for her productions.[25]

L'île du rêve was premiered in 1898, when thanks to Massenet's influence the Opéra-Comique staged the piece, with a fine cast, conducted by André Messager.[26] The press notices were hostile,[26] and the piece was withdrawn after seven performances.[27] While it was in rehearsal Paris was agog at the Zola trial in the continuing Dreyfus affair. The affair sharply divided French opinion; Hahn, like Proust and Bernhardt, was in the Dreyfusard camp. The antisemitic overtones of the anti-Dreyfusard campaign disturbed him deeply, but his devotion to France was unshaken.[13]

In 1898, following the success of his first set of 20 mélodies, published two years earlier, Hahn began composing a second set. which he worked on for more than 20 years.[13] In the same year he started work on 12 "Rondels" for soloists, chorus and piano, completed the following year.[13] In 1899, following the long tradition of French composers supplementing their income by writing music reviews, he became critic for La Presse.[28][n 1]

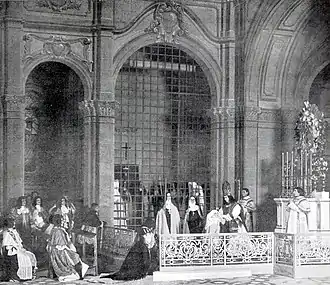

In December 1902 Hahn's second opera, La Carmélite, described as "a musical comedy", with a libretto by Catulle Mendès, was premiered at the Opéra-Comique. Emma Calvé played the main role of Louise de La Vallière, Messager was once again the conductor, and the piece was lavishly mounted,[33] but it was received politely rather than with enthusiasm, and did not gain a place in the operatic repertoire.[13] Its prospects were not helped by the Opéra-Comique's decision to yield to religious lobbyists and cut the climactic scene in which Louise takes the veil;[34][n 2] that scene won critical praise as "inspired", whereas the rest of the score was thought to be skilful, pretty and spirited but lacking in character.[33][35]

Following this disappointment, Hahn turned his attention away from opera. In 1905 he composed one of his most popular works, the suite for chamber ensemble Le Bal de Béatrice d'Este; in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Patrick O'Connor observes that this work, "conceived merely as a divertissement", has remained one of the composer's best-known and most frequently performed.[13]

Hahn began to attract notice as a conductor. Performances of Don Giovanni under his baton in 1903 were praised for his "flexible and light touch" and for his scholarly – and at the time unusual – fidelity to Mozart's score.[36] In 1906 he and Gustav Mahler were the conductors for the two operas given at the Salzburg Festival, celebrating Mozart's 150th anniversary. Mahler conducted The Marriage of Figaro; Hahn conducted Don Giovanni with the Vienna Philharmonic and a cast including Lilli Lehmann and Geraldine Farrar.[37]

In December 1907 Hahn became a naturalised French citizen.[38] In that year he composed his set of six Songs and Madrigals, setting words by medieval and Renaissance French poets in which he incorporated music in the style of Antoine Boësset, court composer to Louis XIII.[13]

Hahn followed the dances of Le Bal de Béatrice d'Este with two complete ballet scores, La Fête chez Thérèse (1910) and Le Dieu bleu (1912). The latter was the first ballet with a score by a French composer presented by Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets russes; the premiere went well but the piece was overshadowed by two other ballets with French scores presented later in the season: Debussy's L'Après-midi d'un faune and Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé.[39][40]

1914 to 1929

At the outbreak of war in 1914 Hahn, who was over the official age limit for conscription, volunteered for the army as a private.[13] For most of the war he served as an adjutant's clerk, working near the front, under frequent bombardment.[41] When possible he continued to compose, writing music for his regiment, contributing to revues for the troops, and working on two new operas, one based on the Odyssey and the other on The Merchant of Venice. He set five verses by Robert Louis Stevenson as a song cycle for children. In 1917 he was promoted to corporal as a despatch rider, and in the last year of the war he was posted to the Ministry of War in Paris as a cipher clerk.[41] For his wartime services he was awarded the Croix de guerre and appointed to the Legion of Honour.[42]

When Hahn returned to civilian life, Cortot, director of the newly founded École Normale de Musique de Paris, appointed him professor of interpretation and singing.[43] Hahn was known for the high standards he expected of singers, and published articles and a book, Du chant (1921), on interpretation and singing technique.[44] In 1919 he met the tenor Guy Ferrant, with whom he began a lifelong and happy personal partnership.[45]

In 1921 Hahn was invited by an old friend, the playwright Robert de Flers, to compose the music for an operetta for which Flers and his collaborator Francis de Croisset had written the libretto. Hahn had reservations: the piece was set in the market of Les Halles, which was the setting for Charles Lecocq's opéra comique La fille de Madame Angot, written fifty years earlier but still immensely popular. Furthermore, the heroine was called Ciboulette, meaning "chives", which Hahn thought unromantic, and the most interesting character was neither the heroine nor the hero, but their mentor, "a sort of elderly Rodolfo out of La bohème".[46] Nonetheless, Hahn accepted the invitation.[47]

Between the start of work on Ciboulette and its premiere, Hahn lost his two closest friends. Proust died in November 1922 and Bernhardt the following March.[48] He pressed on with work, and in April 1923 Ciboulette opened at the Théâtre des Variétés. It was well reviewed and was an enormous box office success.[46] It was revived in Paris several times during Hahn's lifetime,[49] and has remained in the repertoire in France, with 21st-century revivals at the Opéra-Comique and elsewhere.[50]

In 1924 Hahn was promoted to officer in the Legion of Honour.[13] The following year he had the second big success of his theatrical career. The actor and playwright Sacha Guitry invited him to write the music for a new comédie musicale called Mozart. The piece was loosely based on the early life of the composer, and was to star Guitry and his wife, Yvonne Printemps, the latter en travesti as the young Mozart. Hahn agreed, and composed a score incorporating various extracts from Mozart's works along with his own original music. The show opened in December 1925 at the Théâtre Édouard VII, receiving enthusiastic reviews: Messager, writing in Le Figaro called it "a piece of rare quality", and commented that the score was so good that it was hard to detect where Mozart's music ended and Hahn's began: this, he said, was the highest possible praise.[51] The show was a popular success in Paris, with, for the time, an excellent run of seven months.[52] The Guitrys then took the production to London in 1926, where it was well received.[53] At the end of that year there were two versions running on Broadway: the Guitry company played the French original for a limited season,[54] and an English translation ran at another theatre, starring Frank Cellier and Irene Bordoni.[55]

1930 to 1947

In 1930 Hahn composed a piano concerto, premiered in February 1931 with its dedicatee, Magda Tagliaferro, as soloist and the composer conducting;[56] according to Grove it became Hahn's best-known concert work.[13] Tagliaferro and Hahn later recorded the work for the gramophone; the recording has been reissued on CD.[57] In 1931 Hahn wrote the music for the opérette Brummell.[13] In 1933 he became Le Figaro's music critic. In the same year, Ciboulette was filmed for the cinema. The young director Claude Autant-Lara made a fairly free adaptation of the stage work, with Simone Berriau in the title role; it opened in Paris in November 1933, and was well received.[58]

Hahn's only major commission for the Paris Opéra was the work based on The Merchant of Venice that he had begun composing during the war. Le marchand de Venise, with a verse libretto by Miguel Zamacoïs, premiered in March 1935. It was received with enthusiasm, and although it was not revived in Paris during Hahn's lifetime it had several new productions later.[13] Guitry and Hahn worked together on another show, O mon bel inconnu (O My Beautiful Stranger, 1933), starring Arletty. The reviewer in Lyrica commented "Is it operetta? No; comic opera? Not that, either; vaudeville? Not in the least. So what is it? I don't know, but it is unpretentious and it is charming". He added, "Neither of the two authors, so admirably gifted, gave the best of themselves, but the crumbs they nonchalantly let fall from their table are still enough to compose a nice meal".[59] Hahn composed the music for two other musical comedies during the 1930s as well as a considerable quantity of incidental music for plays and films.[60]

In the second half of the decade Hahn was again prominent as a conductor, directing performances of The Magic Flute, The Seraglio and The Marriage of Figaro. His fidelity to Mozart was remarked on in the press: after years of productions at the Opéra-Comique in which the composer's recitatives in Figaro were replaced by spoken dialogue, Hahn used a new, more scholarly text edited by Adolphe Boschot.[61][n 3] In the concert hall he formed musical partnerships with younger performers; in addition to Tagliafero, he regularly accompanied Ferrant and the soprano Ninon Vallin.[62]

When the Germans occupied Paris in 1940, Hahn left for the south of France and then for neutral Monaco. He was less at risk there from Nazi anti-Semitic persecution, but narrowly avoided being killed by the explosion of a stray shell from a British submarine aimed at a German warship moored near his rooms on the front at Monte Carlo.[63] He returned to Paris in February 1945, and was elected to the Institut de France's Académie des Beaux-Arts, and appointed director of the Paris Opéra. His last concert work, the Concerto provençal, was premiered in a broadcast by Radiodiffusion Française on 30 July 1945 and given in concert the following April.[64]

In 1946, together with Tagliafero and Vallin, Hahn made a concert tour, performing in London, Geneva, Brussels, Marseilles and Toulon.[65] He was taken ill and an operation was performed to treat a brain tumour, which his doctors believed might have been caused by the explosion in Monte Carlo.[63]

Hahn died in Paris on 28 January 1947, at the age of 72.[66] He was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery, near the grave of Proust.[67]

Works

.jpg.webp)

Graham Johnson writes that Hahn "was never truly of the twentieth century";[7] he was for many years regarded chiefly as evoking the spirit of fin de siècle Paris.[13] He was not in sympathy with the more obviously modern music of the early decades of the 20th century, but he moved with the times.[7] According to a 2020 analysis:

Hahn's biographer Jacques Depaulis writing in 2006, comments that many composers suffer a period of neglect after their deaths and are then rediscovered, a process known in France as "la traversée du désert" – crossing the desert.[69] In 1947 a British newspaper remarked that Hahn "is hardly remembered today outside the boundaries of France".[70] In 1961, 14 years after the composer's death, the musicologist Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt dismissed Hahn as "a talented gossip who had a gift for grinding out operettas and little, tastefully performed ballads in limitless quantities".[71][n 4] In the last decades of the 20th century there was a revival in interest in Hahn's music: Johnson (2002) refers to "an ever-widening range of his mélodies to be heard regularly on the concert platform".[16]

Mélodies

Hahn is best known for his songs. He wrote just over 100; most were composed in the thirty-year period from 1888 to the end of the First World War, after which the demand for songs with piano accompaniment diminished and he turned to other forms.[13] His style, in his early songs, reflects the influence of Massenet,[73] but he regarded Gabriel Fauré as the supreme master of the mélodie, and favoured some of Fauré's chosen poets, including Victor Hugo, Théophile Gautier and Paul Verlaine.[7] He was only thirteen when he wrote the Hugo setting "Si mes vers avaient des ailes", later included in his first collection of 20 Mélodies (1895). Johnson writes that the song displays all the distinguishing marks of the composer's style:

His first published set of songs was Chansons grises (Songs in Grey, 1890), which included a setting of Verlaine's "La bonne chanson" that the poet preferred to Fauré's well known version of it.[15] The commentator James Day observes that the songs in the set display "a maturity quite remarkable in a sixteen-year-old – and an empathy with the poet quite unexpected in a musician of any age".[74]

After Chansons grises Hahn composed further song cycles over the next 25 years. Rondels (1898–99), with words by Charles d'Orléans, Théodore de Banville and Catulle Mendès, was an example of the composer's fascination with the past, setting original and modern versions of the old rondel verse form.[7] In Études latines (1900) Hahn set ten verses by Leconte de Lisle, evoking Graeco-Roman antiquity. In three of the songs the soloist and pianist are joined by a chorus.[7] Hahn again experimented with combinations of voices in Venezia (1901), a set of six lyrics in Venetian dialect, in which the final song is a duet for tenor and soprano with chorus.[75] For Les feuilles blessés (The Injured Leaves, 1901–1906) Hahn turned to a contemporary poet, Jean Moréas, known for his symbolist verse.[76] In 1907 Hahn returned to older forms with Chansons et madrigaux, setting words by d'Orléans, Jean-Antoine de Baïf and others, in a cycle of six songs for four voices.[77] Love Without Wings (1911) is a set of three verses in English by Mary Robinson, and Hahn again set English texts in Five Little Songs (1915), with verses by Robert Louis Stevenson.[78] Grove lists a final cycle, Chansons espagnoles (1947).[13]

In addition to the song cycles, two collections of Hahn's mélodies, comprising twenty songs each, were published during his lifetime. Both sets include some songs previously published individually, and there were twelve other songs not part of a cycle or included in a published collection.[79]

Operas, opérettes and musical comedies

Hahn completed five operas, and left an incomplete one. The first, L'Île du rêve, an "idylle polynésienne" in three acts, has a libretto by André Alexandre and Georges Hartmann, adapted from Pierre Loti's semi-autobiographical 1880 novel Rarahu or Le Mariage de Loti set in Tahiti.[80] It ran for seven performances in 1898,[81] and was revived at Cannes in 1942, conducted by the composer,[82] but was not seen again in Paris until 2016, when a production from the Théâtre de la Coupe d'Or, Rochefort was presented at the Théâtre de l'Athénée.[83] Henri Büsser considered the work "charming … very musical";[84] it is through-composed and there are no set-piece numbers. Hahn makes use of leitmotifs, following the example of Massenet.[82]

La Carmélite (1902), a period piece set in the reign of Louix XIV, made little impact, although its conductor, Messager, who was musical director at Covent Garden as well as at the Opéra Comique, considered staging it in London; the idea was not realised.[85] Neither of Hahn's next two operas – Nausicaa (1919, libretto by René Fauchois) and La Colombe de Bouddha (Buddha's Dove, 1921), a one-act work with words by André Alexandre[n 5] – was written for Paris, and neither was staged there. The former was given at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo, and the latter at the Théâtre du Casino municipal de Cannes, where Hahn conducted frequently.[87]

Le Marchand de Venise (1935) was the most successful of Hahn's serious operas. It was well received; Büsser wrote:

Other critics noted the Mozartian lightness of the score, and Hahn's view of Shakespeare's drama as a comedy rather than a tragedy.[88] After the opera had its American premiere, the critic Herbert Kupferberg described it as "charming and dramatic", and called for a recording.[89] The piece has been revived by the Opéra-Comique (1979) and at the Grand Théâtre Massenet, Saint-Étienne (2015).[90] Hahn left an unfinished opera, Le Oui des jeunes filles (The Maidens' Consent), which Büsser completed; it was given by the Opéra-Comique company in June 1949.[91]

Ciboulette, Hahn's first venture into opérette, was his most successful and enduring. In a study of opérette, James Harding writes that Hahn's score, though in the tradition of earlier composers, specifically Lecocq, "rejuvenates the old technique with a singular brightness of melody and adroit combinations of voice and instrument".[46] After the initial run in 1923, there were revivals in Paris in 1926, 1931 and 1935,[92] and after Hahn's death there were revivals at the Opéra-Comique in 1953, 2013 and 2014.[93] When the work was first given in London, eighty years after the Paris premiere, the critic Michael Kennedy wrote, "I cannot imagine why it is not in the regular international repertoire, for in many respects it is the equal of Fledermaus and The Merry Widow … there is not a weak number in the piece".[94] Hahn wrote two more opérettes, which were well received without rivalling the success of Ciboulette: Brummell (1931) and Malvina (1935).[95]

Next to Ciboulette, Hahn's biggest box-office success was the "comédie musicale" Mozart, written with Sacha Guitry. Harding describes the piece as "a slim tracery of eighteenth-century allusion gilded by Sacha's unerring wit".[96] Printemps had a great success in the title role, but the piece was successfully revived later with other stars: 1951 with Jeanne Boitel, 1952 with Graziella Sciutti and 2009 and 2011 with Sophie Haudebourg.[83] Further musical comedies followed: Le Temps d'aimer (1926), Ô mon bel inconnu (1933, with Guitry), and Beaucoup de bruit pour rien (Much Ado About Nothing, 1936), a "comédie musicale shakespearienne".[97]

Orchestral and concertante

Among the best known of Hahn's orchestral works is the suite Le Bal de Béatrice d'Este (1905), for a small ensemble of wind instruments, harps, piano and percussion. Evoking a 15th-century Italian court entertainment it displays Hahn's abilities as a pasticheur. Grove describes it as a divertissement,[13] and a later work by Hahn is specifically so labelled, the Divertissement pour une fête de nuit, for wind instruments (including saxophone), piano, string quartet and orchestra (1931).[98]

Hahn wrote two concertos for soloist and conventional orchestral forces. The Violin Concerto (1928) is the larger-scale of the two. The opening movement, marked "Décidé", is richly scored, moving between strongly rhythmical and lyrical passages. The central movement, "Chant d'amour", subtitled "Souvenir de Tunis" evokes the heat and languor of North Africa. In 2002 a Gramophone reviewer wrote that it "hovers between dance and delirium".[99] The finale opens gently, before accelerating into a lively concluding dance. Reviewing the first performance, Paul Bertrand wrote in Le Ménestrel, "This Concerto is, in fact, from a purely musical point of view, a miracle of taste, of delicacy, and it is at the same time marvellously suited to highlighting all the qualities of the performer and to earning him the greatest success".[100] The Piano Concerto (1931) is a lighter-weight piece; the second movement lasts less than three minutes.[99] The concerto is described in The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music as "a charming work" with an opening theme that has "an English flavour, easily lyrical" leading to variations "full of sharp, sparkling contrasts … although no deep emotions are touched this is a delightful piece".[101]

For the theatre, Hahn composed incidental music for more than 20 productions between 1890 and 1939, employing a variety of forces, from mezzo-soprano and children's chorus or soloists and two pianos to full orchestra. Playwrights ranged from Daudet and Hugo to Racine, and Miguel Zamacois.[102] In 1934 he wrote scores for a film adaptation of La Dame aux Camélias and Léonce Perret's Sapho.[103] As well as the 1912 Diaghilev ballet Le Dieu bleu, he supplied original ballet or other dance scores for five other theatrical productions between 1892 and 1939.[104]

Chamber and solo piano

Hahn, whose musical outlook was shaped in the 19th century, regarded Fauré as the last great composer,[105] and musical analysts have noted the older composer's influence in several of Hahn's chamber works. In the Piano Quintet (written in 1922 and published the following year) there are stylistic and thematic echoes of Fauré, particularly in the C-sharp minor slow movement, although in a 2001 analysis Francis Pott also notes the influence of Dvořák.[106] In the Violin Sonata (1926) there are further echoes of Faure's music in the opening movement ("imbued with Gallic restraint and supple expressivity" according to the commentator Jeremy Filsell), but Hahn departs from convention by making much of the last movement gentle and melancholic, rather than boisterous.[107] The Piano Quartet (1946), a late work, is in three movements, and alternates serene passages and more turbulent sections. Like the Violin Sonata, it is a concise work, taking a little over 20 minutes in performance.[107]

Most of Hahn's works for solo piano come from the first half of his career. Some are in conventional forms, including a set of ten waltzes (1896), a sonatine (1907), Thème varié sur le nom de Haydn (1910) and two études (1927, his only post-war piano works).[108] The sonatine is a full-scale piano sonata but, like Ravel, Hahn was daunted by any possible comparison with Beethoven's late piano sonatas, and preferred the more modest title.[109] Other solo piano works are in unusual forms, such as the Portraits de peintres (1894), written to be played between spoken verses, or Le Rossignol éperdu (The Distraught Nightingale), Hahn's most extensive piano work, composed between 1902 and 1910 and published in 1913, consisting of 53 short pieces, grouped into four sections.[110] Hahn wrote five works for piano four hands and four for two-piano duet.[13]

Recordings

During the composer's lifetime there were many recordings, especially of his most popular mélodies, which, according to Depaulis, almost all the great recital singers enjoyed performing.[111] Hahn made numerous recordings, singing and accompanying himself not only in his own songs, but also numbers by Mozart, Gounod, Chabrier, Massenet, Bizet and Offenbach.[112] In the mid-20th-century, singers who made recordings of numerous Hahn songs included Jacques Jansen and Géori Boué.[111] Since interest in Hahn's works revived in the late 20th century recordings of a substantial part of his oeuvre have been released. In 2006 Depaulis listed recordings of Hahn mélodies by, among others, the sopranos Mady Mesplé and Felicity Lott, the mezzo-sopranos Susan Graham, Marie-Nicole Lemieux and Anne-Sofie von Otter, the tenors Martyn Hill and Ian Bostridge and the baritones Didier Henry and Stephen Varcoe.[111] Since then issues have included a 2019 four-disc CD set from the Centre de musique romantique française, "Reynaldo Hahn: Complete Songs", comprising 107 songs, sung by Tassis Christoyannis, accompanied by Jeff Cohen.[113]

Hahn's complete piano music for two players has been recorded by Kun-Woo Paik and Hüseyin Sermet.[114] In the 21st century Earl Wild's complete set of Le Rossignol éperdu (2001), has been followed by further such sets from Cristina Ariagno (2011), Billy Eidi (2015) and Yoonjung Han (2019).[115] In 2015 a four-disc CD set entitled "Hahn: Intégrale Piano Music", played by Alessandro Deljavan was released on the Aevea label.[116]

Of Hahn's stage works, Ciboulette was recorded by EMI in 1983, with a cast headed by Mesplé in the title role, and José van Dam (Duparquet) and Nicolai Gedda (Antonin).[117] The work was recorded again in 2013 at the Opéra-Comique, conducted by Laurence Equilbey; audio and video versions were published.[118] In 2020 Hervé Niquet conducted the first recording of L'île du rêve, released on the Bru Zane label.[68] Yvonne Printemps recorded excerpts from Mozart in 1925 with an orchestra conducted by Marcel Cariven;[119] among later recordings of music from the piece, the complete score was recorded by RTF Radio Lyrique in 1959, with a cast headed by Boué, conducted by Pierre-Michel Le Conte.[120] A recording of a 1963 broadcast of Brummell conducted by Cariven was released as a CD set in 2018.[121] A recording of a 1971 ORTF broadcast of O mon bel inconnu was issued on CD.[122]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- Berlioz, Fauré, Messager, Dukas and Debussy were regular music critics for Parisian journals.[29][30][31][32]

- The scene had been submitted to and approved by the Archbishop of Paris, Cardinal Richard, but a vociferous lobby insisted that sacred rites must not be depicted on stage.[34]

- The authenticity of the score extended to the inclusion of the last-act arias for Basilio and Marcellina, usually cut, but there was no ornamentation and the recitatives were accompanied on the piano rather than the harpsichord.[61]

- Lionel Salter pointed out in Gramophone that as to "limitless quantities", Hahn wrote about the same number of mélodies as Debussy, and far fewer than Fauré.[72]

- Hahn called the piece a "conte lyrique japonais", and sources differ as to whether it should be classed as an opera or an opérette.[86]

References

- Depaulis (2007), p. 16

- Prestwich, p. 14

- Depaulis (2006), p. 264

- Quinn, Michael. "Will the Real Reynaldo Hahn Please Stand Up?", Gramophone, November 2004, p. A15

- Gavoty, p. 37

- Depaulis (2007), p. 19

- Johnson, Graham (1996). Notes to Hyperion CD set CDA67141/2 OCLC 40723495

- Prestwich, pp. 15–16

- Massenet, pp. 27–28

- Gavoty, p. 39

- Harding (1965), p. 201

- "Nouvelles" and "Si mes vers avaient des ailes", Le Figaro, 16 May 1890, pp. 2 and 8

- O'Connor, Patrick "Hahn, Reynaldo", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 29 October 2020 (subscription required)

- Noël and Stoullig, p. 189

- Johnson, p. 236

- Johnson, p. 235

- Carter, p. 167

- Giroud, pp. 38–39

- Ashley, Tim. "Hahn: Concerto provençal; Divertissement", Gramophone, September 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2020 (subscription required) Archived 2 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Harding, James (1989). Notes to Hyperion CD CDH55167 OCLC 57936575

- "France", The Times, 8 May 1896, p. 5; and Nichols, p. 23

- Prestwich, pp. 48–49

- Etienne, Jean-Christophe (2012). Notes to Concerto CD 2015 OCLC 1001864763

- Prestwich, p. 20

- Prestwich, p. 50

- Giroud, p. 35

- Noël and Stoullig, p. 144

- Depaulis (2007), p. 58

- Kolb, p. 1

- Nectoux, Jean-Michel. "Fauré, Gabriel (Urbain)", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press 2001. Retrieved 31 October 2020 (subscription required)

- Schwartz, Manuela and G. W. Hopkins. "Dukas, Paul", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press 2001. Retrieved 31 October 2020 (subscription required)

- Lesure, François, and Roy Howat. "Debussy, (Achille-)Claude", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press 2001. Retrieved 31 October 2020

- Stoullig (1903), p. 131

- "Paris Jottings", The Graphic, 3 January 1903, p. 22

- Harcourt, Eugène d'. "Opéra-Comique", Le Figaro, 17 December 1902, p. 4

- Bellaigue, Camille. "Revue musicale", Revue des Deux Mondes, 1 January 1904, p. 228

- "Music and Musicians", The Morning Post, 9 July 1906, p. 9

- Certificate of naturalisation, Ministère de la Justice, République Française, 9 December 1907

- Scheijen, p. 244

- Grigoriev, pp. 78 and 80

- Prestwich, pp. 241–242

- Depaulis (2006), p. 92

- Gavoty, p. 270

- Du chant, OCLC 559587988

- Gallo, pp. 63–65

- Harding (1979), p. 160

- Harding (1979), p. 159

- Prestwich, p. 244

- Gänzl, p. 377

- "Ciboulette", Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 1 November 2020

- Messager, André "Les premières", Le Figaro, 3 December 1925, p. 4

- "Guitry Season", The Stage, 24 June 1926, p. 16

- "His Majesty's Theatre", The Times, 25 June 1929, p. 14; "A Playgoer's Notebook", The Graphic, 3 July 1926, p. 29

- "Mozart", Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 2 November 2020

- "Mozart", Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 2 November 2020

- Depaulis (2006), p. 286

- APR CD set APR 7312 (2020)

- Depaulis (2007), pp. 107 and 167

- Thomas-Salignac, E. "Bouffes-Parisiens", Lyrica, December 1933, p. 2482

- Prestwich, pp. 245–246

- Bidou, Henry. "La Musique", Les Temps, 29 July 1939, p. 3

- Prestwich, p. 246

- Harding (1979), p. 165

- Tchamkerten, Jacques (2015). Notes to Timpani CD 1C1231 OCLC 949677921

- Prestwich, p. 249

- "M. Reynaldo Hahn", The Times, 31 January 1947, p. 7

- "Division 85", Le Cimetiere du Père Lachaise, Paristoric. Retrieved 4 November 2020

- Notes to Bru Zane recording BZ1042 ISBN 978-84-09-21786-1

- Depaulis (2006), p. 308

- "Obituary: Reynaldo Hahn", The Manchester Guardian, 3 February 1947, p. 3

- Stuckenschmidt, p. 43

- Salter, Lionel. "Hahn Songs", Gramophone", August 1988

- Johnson, p. 237

- Day, James (1982). Notes to Hyperion CD Helios 55040 OCLC 716600601

- Hahn (1901), pp. 27–30

- Depaulis (2007), pp. 162–163

- Depaulis (2006), pp. 276–277

- Depaulis (2006), pp. 272 and 273

- Labartette, Sylvain Paul. " Préambule: Reynaldo Hahn et la mélodie", Association Reynaldo Hahn. Retrieved 6 November 2020

- Stoullig (1899), pp. 105–108

- Stoullig (1899), p. 144

- Giroud, pp. 37–38

- "Reynaldo Hahn", Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 9 November 2020

- Büsser, Henri. "Le Souvenir de Reynaldo Hahn", Revue des deux mondes, January 1964, pp. 110–121 (subscription required)

- "Music, Art and the Drama", The Daily News, 12 January 1903, p. 6; and "Music and Musicians", The Morning Post, 23 February 1903, p. 8

- Depaulis (2006), p. 279; and "Opérettes", Association Reynaldo Hahn. Retrieved 9 November2020

- Depaulis (2006), pp. 278–279

- Vuillermoz, Émile. "Théatres", Excelsior, 23 March 1935, p. 6; and Le Flem, Paul. "La Vie du spectacle", Comoedia, 23 March 1935, p. 1

- Kupferberg, Herbert. "What's Up", Akron Beacon Journal, 20 February 1994, p. 150

- "Le Marchand de Venise" and "Le Marchand de Venise", Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 10 November 2020

- Depaulis (2006), p. 278

- Gänzl and Lamb, p. 457

- "Ciboulette", Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 9 November 2020

- Kennedy, Michael. "How to enslave and enchant a critic", The Sunday Telegraph, 30 March 2003 (subscription required)

- Depaulis (2007), pp. 122, 138 and 152

- Harding (1979), p. 161

- Depaulis (2006), p. 280

- Depaulis (2006), p. 287

- "Reynaldo Hahn Collection", Gramophone, January 2002. Retrieved 7 November 2020

- Bertrand, Paul. "Concerts Colonne", Le Ménestrel, 2 March 1928, p. 97

- March, pp. 526–527

- Depaulis (2006), pp. 282–284

- Depaulis (2006), pp. 284–285

- Depaulis (2006), pp. 281–282

- Coombs, Stephen (2004). Notes to Hyperion CD CDH55379 OCLC 779741182

- Pott, Francis (2001). Notes to Hyperion CD CDA 67258 OCLC 873059225

- Filsell, Jeremy (2004). Notes to Hyperion CD CDH55379 OCLC 779741182

- Depaulis (2006), 291–292 and 294

- "Sonatine", Association Reynaldo Hahn. Retrieved 9 November 2020

- Depaulis (2006), pp. 292–294

- Depaulis (2006), p. 303

- Notes to Romophone CD 82015-2 (2000), OCLC 45501613

- Bru Zane CD set BZ2002 OCLC 1144493629

- Naïve CD sets V4658 (1992) and V4904 (2004), OCLC 229773956 and OCLC 705002158

- WorldCat OCLC 885059865, OCLC 1158934163, OCLC 908432007 and OCLC 1090890639

- Aevea CD set 15001 OCLC 927456998

- Depaulis (2006), p. 307

- WorldCat OCLC 985726731 and OCLC 904483072

- "Mozart", L'encyclopédie multimedia de la comédie musicale théâtrale en France. Retrieved 7 November 2020

- WorldCat OCLC 635343515

- WorldCat OCLC 1053821323

- "Notice bibliographique", Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 7 November 2020

Books

- Carter, William (2000). Marcel Proust: A Life. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09400-8.

- Depaulis, Jacques (2007). Reynaldo Hahn (in French). Biarritz: Atlantica. ISBN 978-2-84049-484-3.

- Gallo, Rubén (2014). Proust's Latin Americans. Baltimore: JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1346-4.

- Gänzl, Kurt (2001). The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre. New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 978-0-02-864970-2.

- Gänzl, Kurt; Andrew Lamb (1988). Gänzl's Book of the Musical Theatre. London: The Bodley Head. OCLC 966051934.

- Gavoty, Bernard (1976). Reynaldo Hahn: le musicien de la Belle Époque (in French). París: Buchet Chastel. OCLC 954560497.

- Giroud, Vincent (2020). "A Polynesian idyll in the time of Gauguin". L'Île du rêve. Venice: Centre de musique romantique française. ISBN 978-84-09-21786-1.

- Grigoriev, S. L. (1960). The Diaghilev Ballet, 1909–1929. Harmondsworth: Penguin. OCLC 1033647372.

- Harding, James (1965). Saint-Saëns and his Circle. London: Chapman & Hall. OCLC 1071102794.

- Harding, James (1979). Folies de Paris: The Rise and Fall of French Operetta. London: Chappell and Elm Tree Books. ISBN 978-0-903443-28-9.

- Giroud, Vincent (2020). "A Polynesian idyll in the time of Gauguin". L'Île du rêve. Venice: Centre de musique romantique française. ISBN 978-84-09-21786-1.

- Hahn, Reynaldo (1901). Venezia (PDF). Paris: Heugel. ISBN 9780720616804. OCLC 844323412.

- Johnson, Graham (2002). A French Song Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924966-4.

- Kolb, Katherine (2014). Berlioz on Music: Selected Criticism, 1824–1837. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939195-0.

- Massenet, Jules (1919) [1910]. My Recollections. Boston: Small Maynard. OCLC 774419363.

- Nichols, Roger (2011). Ravel: A Life. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10882-8.

- Noël, Edouard; Edmond Stoullig (1891). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1890. Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 172996346.

- Prestwich, P. F. (1999). The Translation of Memories: Recollections of the Young Proust. London: Peter Owen. ISBN 978-0-7206-1056-7.

- Scheijen, Sjeng (2010). Diaghilev: A Life. London: Profile. ISBN 978-1-84765-245-4.

- Stoullig, Edmond (1899). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1898. Paris: Ollendorff. OCLC 172996346.

- Stoullig, Edmond (1903). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1902. Paris: Ollendorf. OCLC 172996346.

- Stuckenschmidt, Hans Heinz (1968). Maurice Ravel: Variations on his Life and Work. Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company. ISBN 9780720616804. OCLC 1150275875.

Journals

- Depaulis, Jacques (October–December 2006). "Un compositeur français sous-estimé: Reynaldo Hahn". Fontes Artis Musicae (in French). 53 (4): 263–308. JSTOR 23510460. (subscription required)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reynaldo Hahn. |

- Association Reynaldo Hahn (in French)

- Le Amis de la musique française (in French)

- Biography, Musicologie.org (in French)

- Free scores by Reynaldo Hahn at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Reynaldo Hahn in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)