Rhapsody in Blue

Rhapsody in Blue is a 1924 musical composition by the American composer George Gershwin for solo piano and jazz band, which synthesizes elements of classical music with jazz-influenced effects. The composition was commissioned at the request of bandleader Paul Whiteman.[1] The piece received its premiere in the concert, "An Experiment in Modern Music,"[2] which was held on February 12, 1924, in Aeolian Hall, New York City, by Whiteman and his band with Gershwin playing the piano.[3] The work was orchestrated by Ferde Grofé several times, including the original 1924 scoring, the 1926 "theater orchestra" setting, and the 1942 symphony orchestra scoring.

| Rhapsody in Blue | |

|---|---|

| by George Gershwin | |

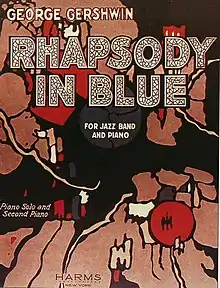

Cover of the original sheet music of Rhapsody in Blue | |

| ISWC | T-070.126.537-3 |

| Genre | Orchestral jazz |

| Form | Rhapsody |

| Composed | January 1924 |

| Premiere | |

| Date | February 12, 1924 |

| Location | Aeolian Hall, New York City, New York, US |

| Conductor | Paul Whiteman |

| Performers | George Gershwin (piano) Ross Gorman (clarinet) |

| Recordings | |

The United States Marine Band's 2018 performance of the 1924 jazz band version

| |

George Gershwin's 1924 performance with Paul Whiteman's orchestra

| |

The rhapsody is regarded as one of Gershwin's most recognizable creations and as a key composition which defined the historical period known as the Jazz Age.[4] The Nation has described Gershwin's piece as inaugurating a new era in America's musical history.[5] The editors of the Cambridge Music Handbooks have posited that "the Rhapsody in Blue (1924) established Gershwin's reputation as a serious composer and has since become one of the most popular of all American concert works."[6] The American Heritage magazine notes that the famous opening clarinet glissando has become as instantly recognizable to concert audiences as Beethoven's Fifth.[7]

History

Commission

Following the success of an experimental classical-jazz concert held with Canadian singer Éva Gauthier in New York City on November 1, 1923, bandleader Paul Whiteman decided to attempt a more ambitious feat.[1] He asked composer George Gershwin to write a concerto-like piece for an all-jazz concert in honor of Lincoln's Birthday to be given at Aeolian Hall.[8] Whiteman became fixated upon performing such an extended composition by Gershwin after he collaborated with him in The Scandals of 1922.[9] He also had been especially impressed by Gershwin's one-act "jazz opera" Blue Monday.[10] However, Gershwin initially declined Whiteman's request on the grounds that—as there would likely be a need for revisions to the score—he would have insufficient time to compose the work.[11]

Soon after, on the evening of January 3, George Gershwin and lyricist Buddy De Sylva were playing billiards at the Ambassador Billiard Parlor at Broadway and 52nd Street in Manhattan.[12] Their game was interrupted by Ira Gershwin, George's brother, who had been reading the January 4 edition of the New-York Tribune.[11][13] An unsigned article entitled "What Is American Music?" about an upcoming Whiteman concert had caught Ira's attention.[12] The article falsely declared that George Gershwin was already "at work on a jazz concerto" for Whiteman's concert.[1][12]

Gershwin was puzzled by the news announcement as he had politely declined to compose any such work for Whiteman.[14] In a telephone conversation with Whiteman the next morning, Gershwin was informed that Whiteman's arch rival Vincent Lopez was planning to steal the idea of his experimental concert and there was no time to lose.[15] Gershwin was thus finally persuaded by Whiteman to compose the piece.[15]

Composition

With only five weeks remaining until the premiere, Gershwin hurriedly set about composing the work.[12] He later claimed that, while on a train journey to Boston, the thematic seeds for Rhapsody in Blue began to germinate in his mind.[16][15] He told biographer Isaac Goldberg in 1931:

It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty [sic] bang, that is so often so stimulating to a composer.... I frequently hear music in the very heart of the noise. And there I suddenly heard—and even saw on paper—the complete construction of the rhapsody, from beginning to end. No new themes came to me, but I worked on the thematic material already in my mind and tried to conceive the composition as a whole. I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston I had a definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance.[16]

Gershwin began composing on January 7 as dated on the original manuscript for two pianos.[1] He tentatively entitled the piece as American Rhapsody during its composition.[17] The revised title Rhapsody in Blue was suggested by Ira Gershwin after his visit to a gallery exhibition of James McNeill Whistler paintings, which had titles such as Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket and Arrangement in Grey and Black.[17][18] After a few weeks, Gershwin finished his composition and passed the score to Ferde Grofé, Whiteman's arranger.[19] Grofé finished orchestrating the piece on February 4—a mere eight days before the premiere.[19]

Premiere

.jpg.webp)

Rhapsody in Blue premiered during a snowy[20] afternoon on Tuesday, February 12, 1924, at Aeolian Hall, Manhattan.[3] Entitled "An Experiment in Modern Music,"[2] the much-anticipated concert held by Paul Whiteman and his Palais Royal Orchestra drew a "packed audience."[3][21] The excited audience consisted of "Vaudevillians, concert managers come to have a look at the novelty, Tin Pan Alleyites, composers, symphony and opera stars, flappers, cake-eaters, all mixed up higgledy-piggledy."[20] Many influential figures of the era were present, including Carl Van Vechten,[5] Marguerite d'Alvarez,[5] Victor Herbert,[22] Walter Damrosch,[22] Igor Stravinsky,[23] Fritz Kreisler,[24] Leopold Stokowski,[25] John Philip Sousa,[26] and Willie "the Lion" Smith.[26]

In a pre-concert lecture, Whiteman's manager Hugh C. Ernst[27] proclaimed the purpose of the concert was "to be purely educational".[28][27] The selected music was intended to exemplify the "melodies, harmony and rhythms which agitate the throbbing emotional resources of this young restless age."[29] The concert's program was lengthy with 26 separate musical movements, divided into 2 parts and 11 sections, bearing titles such as "True Form Of Jazz" and "Contrast—Legitimate Scoring vs. Jazzing."[30] In the program's schedule, Gershwin's rhapsody was merely the penultimate piece and preceded Elgar's Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1.[31]

Many of the early numbers in the program reportedly underwhelmed the audience, and the ventilation system in the concert hall malfunctioned.[32] Some audience members were departing for the exits by the time Gershwin made his inconspicuous entrance for the rhapsody.[32] The audience purportedly were irritable, impatient, and restless until the haunting clarinet glissando that opened Rhapsody in Blue was heard.[33][2] The distinctive glissando had been created quite by happenstance during rehearsals:

"As a joke on Gershwin.... [Ross] Gorman [Whiteman's virtuoso clarinettist] played the opening measure with a noticeable glissando, 'stretching' the notes out and adding what he considered a jazzy, humorous touch to the passage. Reacting favorably to Gorman's whimsy, Gershwin asked him to perform the opening measure that way.... and to add as much of a 'wail' as possible."[34]

The rhapsody was then performed by Whiteman's orchestra consisting of "twenty-three musicians in the ensemble" with George Gershwin on piano.[35][36] In characteristic style, Gershwin chose to partially improvise his piano solo.[36] Consequently, the orchestra anxiously waited for Gershwin's nod which signaled the end of his piano solo and the cue for the ensemble to resume playing.[36] As Gershwin improvised some of what he was playing, the solo piano section was not technically written until after the performance; hence, it is unknown exactly how the original rhapsody sounded at the premiere.[37]

Audience reaction and success

Upon the conclusion of the rhapsody, there was "tumultuous applause for Gershwin's composition,"[3][38] and, quite unexpectedly, "the concert, in every respect but the financial,[lower-alpha 1] was a 'knockout'."[40] The concert itself would become historically significant due to the premiere of the rhapsody, and its program would "become not only a historic document, finding its way into foreign monographs on jazz, but a rarity as well."[20]

Following the success of rhapsody's premiere, future performances followed. The first British performance of Rhapsody in Blue took place at the Savoy Hotel in London on June 15, 1925.[41] It was broadcast in a live relay by the BBC. Debroy Somers conducted the Savoy Orpheans with Gershwin himself at the piano.[41] The piece was heard again in the United Kingdom during the second European tour of the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, most notably on April 11, 1926, at the Royal Albert Hall, with Gershwin in the audience. The Royal Albert Hall concert was recorded—though not issued—by the British record label His Master's Voice.[42][43]

By the end of 1927, Whiteman's band had performed Rhapsody in Blue approximately 84 times, and its recording sold a million copies.[7] However, in order for the entire piece to fit onto two sides of a 12-inch record, the rhapsody had to be played at a faster speed than usual in a concert, which gave it a hurried feel and some rubato was lost. Whiteman later adopted the piece as his band's theme song and opened his radio programs with the slogan "Everything new but the Rhapsody in Blue."[44]

Contemporary reviews

— Lawrence Gilman, New-York Tribune, February 1924[45]

In contrast to the warm reception by concert audiences,[40][3] professional music critics in the press gave the rhapsody decidedly mixed reviews.[46] Pitts Sanborn declared that the rhapsody "begins with a promising theme well stated" yet "soon runs off into empty passage-work and meaningless repetition."[38] A number of reviews were particularly negative. One opinionated music critic, Lawrence Gilman—a Richard Wagner enthusiast who would later write a devastating review of Gershwin's Porgy and Bess—harshly criticized the rhapsody as "derivative," "stale," and "inexpressive" in New-York Tribune review on February 13, 1924.[47][45]

Other reviewers were more positive. Samuel Chotzinoff, music critic of the New York World, conceded that Gershwin's composition had "made an honest woman out of jazz,"[22] while Henrietta Strauss of The Nation opined that Gershwin had "added a new chapter to our musical history."[5] Olin Downes, reviewing the concert in The New York Times, wrote:

This composition shows extraordinary talent, as it shows a young composer with aims that go far beyond those of his ilk, struggling with a form of which he is far from being master.... In spite of all this, he has expressed himself in a significant and, on the whole, highly original form.... His first theme... is no mere dance-tune... it is an idea, or several ideas, correlated and combined in varying and contrasting rhythms that immediately intrigue the listener. The second theme is more after the manner of some of Mr. Gershwin's colleagues. Tuttis are too long, cadenzas are too long, the peroration at the end loses a large measure of the wildness and magnificence it could easily have had if it were more broadly prepared, and, for all that, the audience was stirred and many a hardened concertgoer excited with the sensation of a new talent finding its voice.[3]

Overall, a recurrent criticism leveled by professional music critics was that Gershwin's piece was essentially formless and that he had haphazardly glued melodic segments together.[48]

Retrospective reviews

Years after its premiere, Rhapsody in Blue continued to divide music critics principally due to its perceived melodic incoherence.[49] Constant Lambert, a British conductor, was openly dismissive towards the work:

The composer [George Gershwin], trying to write a Lisztian concerto in a jazz style, has used only the non-barbaric elements in dance music, the result being neither good jazz nor good Liszt, and in no sense of the word a good concerto.[50]

In an article in The Atlantic Monthly in 1955, Leonard Bernstein, who nevertheless admitted that he adored the piece,[51] stated:

Rhapsody in Blue is not a real composition in the sense that whatever happens in it must seem inevitable, or even pretty inevitable. You can cut out parts of it without affecting the whole in any way except to make it shorter. You can remove any of these stuck-together sections and the piece still goes on as bravely as before. You can even interchange these sections with one another and no harm done. You can make cuts within a section, or add new cadenzas, or play it with any combination of instruments or on the piano alone; it can be a five-minute piece or a six-minute piece or a twelve-minute piece. And in fact all these things are being done to it every day. It's still the Rhapsody in Blue.[51][52]

Orchestration

As Gershwin did not have sufficient knowledge of orchestration in 1924,[53] Ferde Grofé—Whiteman's pianist and chief arranger—was a key figure in enabling the rhapsody's meteoric success,[54] and critics have contended that Grofé's arrangements of the Rhapsody secured its place in American culture.[55] Gershwin's biographer Isaac Goldberg wrote in 1931:

"In the heat of the [premiere's] occasion, the contribution of Ferdie [sic] Grofé, the arranger on the Whiteman staff who had scored the Rhapsody in ten days, was overlooked or ignored. It is true that an appreciable part of the scoring had been indicated by Gershwin; nevertheless, the contribution of Grofé was of prime importance, not only to the composition, but to the jazz scoring of the immediate future."[54]

Grofé's familiarity with the Whiteman band's strengths was a key factor in his 1924 scoring.[56] Grofé's original orchestration was developed for solo piano and Whiteman's band which consisted of: three woodwind players doubling one oboe, one heckelphone, one clarinet, one sopranino saxophone in E♭, two soprano saxophones in B♭, two alto saxophones in E♭, one tenor saxophone in B♭, one baritone saxophone in E♭; two trumpets in B♭, two French horns in F, two trombones, and one tuba (doubling on double bass).[57] Its percussion section included a drum set, timpani, and a glockenspiel; one piano; one tenor banjo; and violins.[58] This original 1924 version—with its unique instrumental requirements—was largely ignored until its revival in reconstructions beginning in the mid-1980s, owing to the popularity and serviceability of the later scorings.[59]

After the 1924 premiere, Grofé revised the score and made new orchestrations in 1926 and 1942, each time for larger orchestras.[59] His arrangement for a theater orchestra was published in 1926.[60] This adaptation was orchestrated for a more standard "pit orchestra," which included one flute, one oboe, two clarinets, one bassoon, three saxophones; two French horns, two trumpets, and two trombones; as well as the same percussion and strings complement as the later 1942 version.[61]

The later 1942 arrangement by Grofé was for a full symphony orchestra. It is scored for solo piano and an orchestra consisting of two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets in B♭ and A, one bass clarinet, two bassoons, two alto saxophones in E♭, one tenor saxophone in B♭; three French horns in F, three trumpets in B♭, three trombones, one tuba; a percussion section that includes timpani, one suspended cymbal, one snare drum, one bass drum, one tam-tam, one triangle, one glockenspiel, and cymbals; one tenor banjo; and strings. Since the mid-20th century, this 1942 version was the arrangement usually performed by classical orchestras and became a staple of the concert repertoire until 1976 when Michael Tilson Thomas recorded the original jazz band version for the first time, employing Gershwin's actual 1925 piano roll with a full jazz orchestra.[59]

Grofé's other arrangements of Gershwin's piece include those done for Whiteman's 1930 film, King of Jazz,[62] and the concert band setting (playable without piano) completed by 1938 and published 1942. The prominence of the saxophones in the later orchestrations is somewhat reduced, and the banjo part can be dispensed with, as its mainly rhythmic contribution is provided by the inner strings.[63]

Gershwin himself also made versions of the piece for solo piano as well as two pianos.[64] The solo version is notable for omitting several sections of the piece.[lower-alpha 2] Gershwin's intent to eventually do an orchestration of his own is documented in 1936–37 correspondence from publisher Harms.[65]

Notable recordings

Two recordings exist of George Gershwin performing abridged versions of his composition with Paul Whiteman's orchestra.[66][67] A June 10, 1924 acoustic recording[lower-alpha 3] produced by the Victor Talking Machine Company, and running 8 minutes and 59 seconds,[68][69] and an April 21, 1927 electrical recording[lower-alpha 4] made by Victor, running 9 minutes and 1 second (approximately half the length of the complete work).[70] This version was conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret after a quarrel between Gershwin and Whiteman.[71][70] In addition to the aforementioned two versions, a 1925 piano roll captured Gershwin's performance in a two-piano version.[72]

Whiteman's orchestra later performed a truncated version of the piece in the 1930 film The King of Jazz with Roy Bargy on solo piano.[73][74] Whiteman re-recorded the piece for Decca on a 12-inch 78 rpm disc (29051) on October 23, 1938.[75] However, it was not until the Great Depression that the first complete recording of the composition, with pianist Jesús María Sanromá and Arthur Fiedler conducting the Boston Pops Orchestra, was issued by RCA Victor in 1935.

During World War II, a recording by pianist Oscar Levant with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy was made on August 21, 1945.[76] This recording, labelled Columbia Masterworks 251, became one of the best-selling record albums of that year.[76] Over a decade later in 1958, the Hamburg Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Hans-Jürgen Walther and with David Haines on piano recorded an 8:16 version for Somerset Records. The album cover featured a photographie de nuit of the Chrysler Building—an Art Deco-style skyscraper—and the surrounding cityscape with a blue hue.

In 1973, the piece was recorded by Brazilian jazz-rock artist Eumir Deodato on his album Deodato 2. The single reached Billboard peak positions number 41 Pop, number 10 Easy Listening. A disco arrangement was recorded by French pianist Richard Clayderman in 1978 and is one of his signature pieces.

In the late 1970s, interest in the original arrangement was revived. On February 14, 1973, it received its first performance since the Jazz Age: Conductor Kenneth Kiesler secured the requisite permissions and led with work with pianist Paul Verrette on his University of New Hampshire campus.[77] Reconstructions of it have been recorded by Michael Tilson Thomas and the Columbia Jazz Band in 1976, and by Maurice Peress with Ivan Davis on piano as part of a 60th-anniversary reconstruction of the entire 1924 concert.[78] André Watts (1976), Marco Fumo (1974), and Sara Davis Buechner (2005) released recordings of the work for solo piano as did Eric Himy (2004) in a version that featured the untruncated original short score. Meanwhile, such two-piano teams as José Iturbi and Amparo Iturbi as well as Katia and Marielle Labèque also recorded the piece. Michel Camilo recorded the piece in 2006, winning a Latin Grammy Award.[79]

Form and analysis

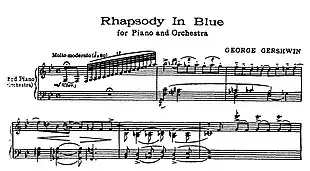

As a jazz concerto, Rhapsody in Blue is written for solo piano with orchestra.[80] A rhapsody differs from a concerto in that it features one extended movement instead of separate movements. Rhapsodies often incorporate passages of an improvisatory nature—although written out in a score—and are irregular in form, with heightened contrasts and emotional exuberance. The music ranges from intensely rhythmic piano solos to slow, broad, and richly orchestrated sections. Consequently, the Rhapsody "may be looked upon as a fantasia, with no strict fidelity to form."[81]

The opening of Rhapsody in Blue is written as a clarinet trill followed by a legato, 17 notes in a diatonic scale. During a rehearsal, Whiteman's virtuoso clarinetist, Ross Gorman, rendered the upper portion of the scale as a captivating and trombone-like glissando.[82] Gershwin heard it and insisted that it be repeated in the performance.[82] The effect is produced using the tongue and throat muscles to change the resonance of the oral cavity, thus controlling the continuously rising pitch.[83] Many clarinet players also gradually open the left-hand tone holes on their instrument during the passage from the last concert F to the top concert B♭ as well. This effect has now become standard performance practice for the work.[83]

Rhapsody in Blue features both rhythmic invention and melodic inspiration, and demonstrates Gershwin's ability to write a piece with large-scale harmonic and melodic structure. The piece is characterized by strong motivic interrelatedness.[84] Much of the motivic material is introduced in the first 14 measures.[84] Musicologist David Schiff has identified five major themes plus a sixth "tag".[17] Of these, two appear in the first 14 measures, and the tag shows up in measure 19.[17] Two of the remaining three themes are rhythmically related to the very first theme in measure 2, which is sometimes called the Glissando theme[17][85]—after the opening glissando in the clarinet solo—or the Ritornello theme.[17][85] The remaining theme is the Train theme,[17][86] which is the first to appear at rehearsal 9 after the opening material.[86] All of these themes rely on the blues scale,[87] which includes lowered sevenths and a mixture of major and minor thirds.[87] Each theme appears both in orchestrated form and as a piano solo. There are considerable differences in the style of presentation of each theme.

The harmonic structure of the rhapsody is more difficult to analyze.[88] The piece begins and ends in B♭ major, but it modulates towards the sub-dominant direction very early on, returning to B♭ major at the end, rather abruptly.[89] The opening modulates "downward", as it were, through the keys B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, B, E, and finally to A major.[89] Modulation through the circle of fifths in the reverse direction inverts classical tonal relationships, but does not abandon them. The entire middle section resides primarily in C major, with forays into G major (the dominant relation).[90] Such modulations occur freely, although not always with harmonic direction. Gershwin frequently uses a recursive harmonic progression of minor thirds to give the illusion of motion when in fact a passage does not change key from beginning to end.[88] Modulation by thirds is a common feature of Tin Pan Alley music.

The influences of jazz and other contemporary styles are present in Rhapsody in Blue. Ragtime rhythms are abundant,[87] as is the Cuban "clave" rhythm, which doubles as a dance rhythm in the Charleston jazz dance.[46] Gershwin's own intentions were to correct the belief that jazz had to be played strictly in time so that one could dance to it.[91] The rhapsody's tempos vary widely, and there is an almost extreme use of rubato in many places throughout. The clearest influence of jazz is the use of blue notes, and the exploration of their half-step relationship plays a key role in the rhapsody.[92] The use of so-called "vernacular" instruments, such as accordion, banjo, and saxophones in the orchestra, contribute to its jazz or popular style, and the latter two of these instruments have remained part of Grofé's "standard" orchestra scoring.[63]

Gershwin incorporated several different piano styles into his work. He utilized the techniques of stride piano, novelty piano, comic piano, and the song-plugger piano style. Stride piano's rhythmic and improvisational style is evident in the "agitato e misterioso" section, which begins four bars after rehearsal 33, as well as in other sections, many of which include the orchestra.[86] Novelty piano can be heard at rehearsal 9 with the revelation of the Train theme. The hesitations and light-hearted style of comic piano, a vaudeville approach to piano made well known by Chico Marx and Jimmy Durante, are evident at rehearsal 22.[93]

Legacy and influence

Cultural zeitgeist

According to critic Orrin Howard of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Gershwin's rhapsody "made an indelible mark on the history of American music, on the fraternity of serious composers and performers—many of whom were present at the premiere—and on Gershwin himself, for its enthusiastic reception encouraged him to other and more serious projects."[94]

Howard posits that the song's legacy is best understood as embodying the cultural zeitgeist of the Jazz Age: "Beginning with that incomparable, flamboyant clarinet solo, Rhapsody is irresistible still, with its syncopated rhythmic vibrancy, its abandoned, impudent flair that tells more about the Roaring Twenties than could a thousand words, and its genuine melodic beauty colored a deep, jazzy blue by the flatted sevenths and thirds that had their origins in the African-American slave songs."[94] Although Gershwin's rhapsody "was by no means a definitive example of jazz in the Jazz Age,"[95] music historians such as James Ciment and Floyd Levin have similarly concurred that it is the key composition that encapsulates the spirit of the era.[96][97]

As early as 1927, writer F. Scott Fitzgerald opined that Rhapsody in Blue idealized the youthful zeitgeist of the Jazz Age.[98] In subsequent decades, both the latter era and Fitzgerald's related literary works have been often culturally linked by critics and scholars with Gershwin's composition.[99] Accordingly, Rhapsody in Blue was used as a dramatic leitmotif for the character of Jay Gatsby in the 2013 film The Great Gatsby, a cinematic adaptation of Fitzgerald's 1925 novel.[100][101]

Various writers, such as American playwright Terry Teachout, have also likened Gershwin himself to the character of Gatsby due to his attempt to transcend his lower-class background, his abrupt meteoric success, and his early death while in his thirties.[99]

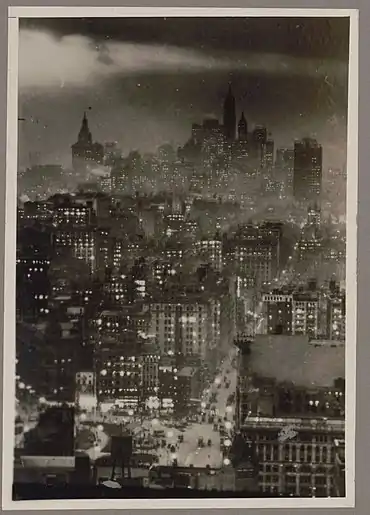

Musical portrait of New York City

Rhapsody in Blue has been also interpreted as a musical portrait of early 20th-century New York City.[102] Culture scribe Darryn King wrote in The Wall Street Journal that "Gershwin's fusion of jazz and classical traditions captures the thriving melting pot of Jazz Age New York."[102]

Likewise, music historian Vince Giordano has opined that "the syncopation, the blue notes, the ragtime and jazz rhythms that Gershwin wrote in 1924 was really a feeling of New York City in that amazing era. The rhythm of the city seems to be in there."[102] Pianist Lang Lang echoes this sentiment: "When I hear Rhapsody in Blue, I see the Empire State Building somehow. I see the New York skyline in midtown Manhattan, and I already see the coffee shops [in] Times Square."[102]

Accordingly, the composition was used in this context in a New York segment for the 1999 Walt Disney Pictures animated film Fantasia 2000, in which the piece is used as the lyrical framing for a stylized animation set drawn in the style of famed illustrator Al Hirschfeld.[103] It was also used in the opening sequence of Woody Allen's 1979 film Manhattan.[104] The film serves as "a cinematic love letter to the city, which set its opening montage of quintessential New York scenes to Gershwin's famed jazz concerto."[102]

Influence on composers

Gershwin's rhapsody has also influenced a number of composers. In 1955, Rhapsody in Blue served as the inspiration for a composition by the noted accordionist/composer John Serry Sr. which was subsequently published in 1957 as American Rhapsody.[105] Brian Wilson, leader of The Beach Boys, stated on several occasions that Rhapsody in Blue is one of his favorite pieces. He first heard it when he was two years old, and recalls that he "loved" it. According to biographer Peter Ames Carlin, it was an influence on his Smile album.[106] Rhapsody in Blue also inspired a collaboration between blind savant British pianist Derek Paravicini and composer Matthew King on a new concerto, called Blue premiered at the South Bank Centre in London in 2011.[107]

Other usages

Rhapsody in Blue was played simultaneously by 84 pianists at the opening ceremony of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.[60][108] Pianists Herbie Hancock and Lang Lang performed Rhapsody in Blue at the 50th Grammy Awards on February 10, 2008.[109] Since 1980,[110] the piece is used by United Airlines in their advertisements, in pre-flight safety videos, and in the Terminal 1 underground walkway at Chicago O'Hare International Airport.[111][112]

Preservation status

On September 22, 2013, it was announced that a musicological critical edition of the full orchestral score will be eventually released. The Gershwin family, working in conjunction with the Library of Congress and the University of Michigan, are working to make these scores available to the public.[113][114] Though the entire Gershwin project may take 40 years to complete, the Rhapsody in Blue edition will be an early volume.[115][116]

Rhapsody in Blue entered the public domain on January 1, 2020, although individual recordings of it may remain under copyright.[117][118]

References

Notes

- Bandleader Paul Whiteman gave away many free tickets to promote the concert and, consequently, lost money.[39] He expended $11,000, and the concert only netted $4,000.[39]

- The omissions include the bars from rehearsal mark 14 to halfway through the fifth bar of rh. 18; from two bars before rh. 22 to the fourth bar of rh. 24; and the first four bars of rh. 38.

- The June 10, 1924 acoustic recording was labeled Victor 55225.[68] It purportedly featured the original clarinetist, Ross Gorman, playing the glissando.[68]

- The April 21, 1927 electrical recording was labeled Victor 35822.[70] Music historian Brian Rust claims the orchestra was directed by Nathaniel Shilkret.[70] This 1927 version was also dubbed onto an RCA Victor 33 1⁄3-rpm Program Transcription in 1932.

Citations

- Schiff 1997, p. 53.

- Cowen 1998.

- Downes 1924, p. 16.

- Ciment 2015, p. 265; Gilbert 1995, p. 71; Howard 2003

- Goldberg 1958, p. 154.

- Schiff 1997, book jacket.

- Schwarz 1999.

- Greenberg 1998, p. 61.

- Wood 1996, pp. 68–69, 112.

- Wood 1996, p. 112; Howard 2003

- Wood 1996, p. 81.

- Schwartz 1979, p. 76.

- Jablonski 1999.

- Schwartz 1979, p. 76; Wood 1996, p. 81; Jablonski 1999

- Greenberg 1998, pp. 64–65.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 139.

- Schiff 1997, p. 13.

- Reef 2000, p. 38.

- Greenberg 1998, p. 69.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 143.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 142.

- Jenkins 1974, p. 144.

- Wood 1996, p. 85; Jenkins 1974, p. 144

- Wood 1996, p. 85; Jenkins 1974, p. 144

- Wood 1996, p. 85; Jenkins 1974, p. 144

- Wood 1996, p. 85.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 144.

- Schwartz 1979, p. 84.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 145.

- Goldberg 1958, pp. 146–147.

- Schiff 1997, pp. 55–61.

- Greenberg 1998, pp. 72.

- Greenberg 1998, pp. 72–73.

- Schwartz 1979, pp. 81–83.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 147.

- Schwartz 1979, p. 89.

- Schwartz 1979, pp. 88–89.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 152.

- Goldberg 1958, pp. 142, 148.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 148.

- Radio Times 1925.

- Royal Albert Hall 1926.

- Rust 1975, p. 1929.

- Rayno 2013, p. 203.

- Jablonski 1992, p. 30.

- Schneider 1999, p. 180.

- Slonimsky 2000, p. 105.

- Greenberg 1998, pp. 74–75.

- Schneider 1999, p. 182; Wyatt & Johnson 2004, p. 297; Schiff 1997, p. 4

- Schneider 1999, p. 182.

- Wyatt & Johnson 2004, p. 297.

- Schiff 1997, p. 4.

- Greenberg 1998, p. 66.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 153.

- Bañagale 2014, pp. 45–46.

- Bañagale 2014, p. 4.

- Sultanof 1987; Levy 2019; Goldberg 1958, p. 148

- Sultanof 1987; Levy 2019; Goldberg 1958, p. 148

- Greenberg 1998, p. 76.

- Bañagale 2014, p. 43.

- Bañagale 2014, p. 44.

- Greenberg 1998, p. 67.

- Schiff 1997, p. 65.

- Ferencz 2011, p. 143.

- Ferencz 2011, p. 141.

- Greenberg 1998, pp. 75.

- Schiff 1997, p. 86.

- Rust 1975, p. 1924.

- Rayno 2013, p. 327.

- Rust 1975, p. 1931.

- Greenberg 1998, pp. 75–76.

- Schiff 1997, p. 64.

- Sobczynski 2018.

- Greenberg 1998, p. 78.

- Rust 1975, p. 1950.

- Billboard 1945, p. 24.

- Smith 1973, p. 10.

- Schiff 1997, pp. 67–68.

- Westphal 2006.

- Schiff 1997, p. 26.

- Goldberg 1958, p. 157.

- Greenberg 1998, p. 70.

- Chen & Smith 2008.

- Gilbert 1995, p. 17.

- Bañagale 2014, pp. 39–42.

- Bañagale 2014, p. 107.

- Schiff 1997, p. 14.

- Gilbert 1995, p. 68.

- Schiff 1997, p. 28.

- Schiff 1997, p. 29.

- Schiff 1997, p. 12.

- Schneider 1999, p. 187.

- Schiff 1997, p. 36.

- Howard 2003.

- Sisk 2016.

- Levin 2002, p. 73.

- Ciment 2015, p. 265.

- Fitzgerald 2004, p. 93.

- Teachout 1992.

- Bañagale 2014, pp. 156–157.

- Levy 2019.

- King 2016.

- Solomon 1999.

- Cooper 2016.

- Serry 1957.

- Carlin 2006, pp. 25, 118.

- BBC News 2011.

- Schiff 1997, p. 1.

- Swed 2009.

- United Airlines 2020.

- Bañagale 2014, pp. 158–173.

- Eldred v. Ashcroft 2003.

- Gershwin Initiative 2013.

- Canty 2013.

- Clague & Getman 2015.

- Clague 2013.

- King & Jenkins 2019.

- Jenkins 2019.

Bibliography

- "A Concert of Syncopated Symphonic Music". Radio Times (90). London, England. June 12, 1925. p. 538. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Bañagale, Ryan Raul (2014). Arranging Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue and the Creation of an American Icon. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199978373.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-997837-3.

- "Best-Selling Record Albums by Classical Artists (1945)". The Billboard. Vol. 57 no. 35. September 1, 1945. p. 24. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "Blind Autistic Man Stuns the Music World". BBC News. London, England. September 28, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- Canty, Cynthia (October 21, 2013). "The University of Michigan Was Selected for the 'Gershwin Initiative'". Ann Arbor, Michigan: Michigan Radio. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Carlin, Peter Ames (2006). Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall and Redemption of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson. London: Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-899-3.

- Clague, Mark (September 20, 2013). "George and Ira Gershwin Critical Edition". Musicology Now. New York: American Musicological Society. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Clague, Mark; Getman, Jessica (2015). "The Editions". The Gershwin Initiative. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Chen, Jer Ming; Smith, John (2008). "How to Play the First Bar of Rhapsody in Blue". Acoustical Society of America. Archived from the original on April 25, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- Ciment, James (2015) [2008]. Encyclopedia of the Jazz Age: From the End of World War I to the Great Crash. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-47165-3. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Cooper, Michael (September 15, 2016). "The Philharmonic Accompanies 'Manhattan,' Just as It Did in 1979". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- Cowen, Ron (1998). "George Gershwin: He Got Rhythm". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Downes, Olin (February 13, 1924). "A Concert of Jazz". The New York Times. New York. p. 16. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- Eldred v. Ashcroft, 01 U.S. 618, p. 67 (United States Supreme Court January 15, 2003) ("Even the $500,000 that United Airlines has had to pay for the right to play George Gershwin's 1924 classic Rhapsody in Blue represents a cost of doing business, potentially reflected in the ticket prices of those who fly.").

- Ferencz, George J. (2011). "Porgy and Bess on the Concert Stage: Gershwin's 1936 Suite (Catfish Row) and the 1942 Gershwin–Bennett Symphonic Picture". The Musical Quarterly. 94 (1–2): 93–155. doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdq019. ISSN 1741-8399. JSTOR 41289202.

Reissuance of The Rhapsody in Blue re-scored by yourself for large symphony orchestra

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (2004). Conversations with F. Scott Fitzgerald. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-605-6.

- Gilbert, Steven E. (1995). The Music of Gershwin. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06233-5.

- Goldberg, Isaac (1958) [1931]. George Gershwin: A Study in American Music. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Company. LCCN 58-11627 – via Internet Archive.

- Greenberg, Rodney (1998). George Gershwin. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3504-4.

- Howard, Orrin (2003). "Rhapsody in Blue". Los Angeles: Los Angeles Philharmonic Association. Archived from the original on February 23, 2005. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- Jablonski, Edward (1992). Gershwin Remembered. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-43-8.

- Jablonski, Edward (1999). "Glorious George". Cigar Aficionado. Archived from the original on January 17, 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- Jenkins, Alan (1974). The Twenties. Great Britain: Peerage Books. ISBN 978-0-434-90894-3. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- Jenkins, Jennifer (December 30, 2019). "Public Domain Day 2020". Duke Law School's Center for the Study of the Public Domain. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- King, Darryn (September 15, 2016). "How 'Rhapsody in Blue' Perfectly Channels New York". The Wall Street Journal. New York. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- King, Noel; Jenkins, Jennifer (December 30, 2019). "1924 Copyrighted Works To Become Part Of The Public Domain". NPR. Archived from the original on January 4, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Levin, Floyd (April 30, 2002). Classic Jazz: A Personal View of the Music and the Musicians. ISBN 978-0-520-23463-5. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- Levy, Aidan (2019). "'Rhapsody In Blue' at 90". JazzTimes. Braintree, Massachusetts.

Like a train, Gershwin's sprawling composition had more moving parts than Whiteman had musicians, even augmented with strings, but the band was so versatile that three reed players managed to play a total of 17 parts, including the oboe-like heckelphone, switching as the music dictated.

- Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra (1926). Paul Whiteman Orchestra — Live at the Royal Albert Hall in 1926 (HMV Recording). Royal Albert Hall. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Rayno, Don (2013). Paul Whiteman: Pioneer in American Music, Volume II: 1930-1967. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8204-1.

- Reef, Catherine (2000). George Gershwin: American Composer. Greensboro, North Carolina: Morgan Reynolds Publishing. ISBN 978-1-883846-58-9.

- "Rhapsody Remastered". United Airlines. 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Rust, Brian (1975). The American Dance Band Discography 1917-1942. 2. New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House. ISBN 0-87000-248-1.

- Schiff, David (1997). Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511620201. ISBN 978-0-521-55077-2.

- Schneider, Wayne, ed. (1999). The Gershwin Style: New Looks at the Music of George Gershwin. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509020-8.

- Schwartz, Charles (1979). Gershwin: His Life and Music. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80096-2 – via Internet Archive.

- Schwarz, Frederick D. (1999). "Time Machine: Seventy-five Years Ago Gershwin's Rhapsody". American Heritage. Vol. 50 no. 1. Archived from the original on May 7, 2006. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- Serry, John (1957). American Rhapsody, Copyright: Alpha Music Co (Report). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress Copyright Office.

- Sisk, Sarah (February 12, 2016). "When Blue Was New: Rhapsody in Blue's Premiere at 'An Experiment in Modern Music'". The Gershwin Initiative. University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas (2000) [1953]. Lexicon of Musical Invective: Critical Assaults on Composers Since Beethoven's Time. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32009-1.

- Sobczynski, Peter (April 9, 2018). "Criterion Returns King of Jazz to Its Rightful Throne". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- Smith, Wayne A. (January 27, 1973). "Around the Clock: Rhapsody Revived". The Greenfield Recorder. Greenfield, Massachusetts. p. 10.

- Solomon, Charles (1999). "Rhapsody in Blue: Fantasia 2000's Jewel in the Crown". Animation World Magazine. Vol. 4 no. 9. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- Sultanof, Jeff, ed. (1987). Rhapsody in Blue: Commemorative Facsimile Edition. Secaucus, New Jersey: Warner Brothers Music.

This reproduces Grofé's holograph manuscript from the Gershwin Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress.

- Swed, Mark (August 8, 2009). "Music Review: Lang Lang and Herbie Hancock at the Hollywood Bowl". Culture Monster. Los Angeles Times. El Segundo, California. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- Teachout, Terry (January 19, 1992). "The Fabulous Gershwin Boys". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "The Gershwin Initiative". University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance. 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Westphal, Matthew (November 3, 2006). "Michel Camilo and Barcelona Symphony Win Classical Latin Grammy for Rhapsody in Blue". Playbill. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- Wood, Ean (1996). George Gershwin: His Life and Music. London: Sanctuary Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86074-174-6.

- Wyatt, Robert; Johnson, John Andrew, eds. (2004). "Leonard Bernstein: "Why Don't You Run Upstairs and Write a Nice Gershwin Tune?" (1955)". The George Gershwin Reader: Readers on American Musicians. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802985-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rhapsody in Blue (Gershwin). |

- Rhapsody in Blue: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Gershwin's Original Manuscript for Rhapsody in Blue at the Library of Congress