River Kennet

The Kennet is a tributary of the River Thames in Southern England. Most of the river is straddled by the North Wessex Downs AONB (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty). The lower reaches have been made navigable as the Kennet Navigation, which – together with the Avon Navigation, the Kennet and Avon Canal and the Thames – links the cities of Bristol and London.

| Kennet | |

|---|---|

The Kennet near Axford, Wiltshire | |

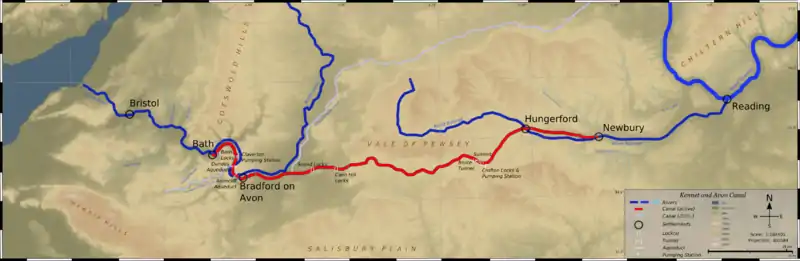

The Avon of North Wiltshire and Somerset (to west, left) and the Kennet flowing into the Thames. Linking canal network in red. | |

| Etymology | Linked to place name: Cunetio (very likely from Celtic kūn, hound) |

| Location | |

| Country | England |

| Counties | Wiltshire, Berkshire |

| Towns | Marlborough, Hungerford, Newbury |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Swallowhead Spring, near Silbury Hill, Wiltshire, United Kingdom |

| • coordinates | 51.50276°N 1.84507°W |

| • elevation | 200 m (660 ft) |

| Mouth | River Thames |

• location | Reading, Berkshire, United Kingdom |

• coordinates | 51.459148°N 0.94947°W |

• elevation | 40 m (130 ft) |

| Length | 72 km (45 mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Theale, Berkshire |

| • average | 9.75 m3/s (344 cu ft/s) |

| • minimum | 0.93 m3/s (33 cu ft/s)21 August 1976 |

| • maximum | 70.0 m3/s (2,470 cu ft/s)11 June 1971 |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Newbury, Berkshire |

| • average | 4.64 m3/s (164 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Knighton, Wiltshire |

| • average | 2.50 m3/s (88 cu ft/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Marlborough, Wiltshire |

| • average | 0.85 m3/s (30 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | River Og, River Lambourn |

| • right | River Dun, River Enborne, Clayhill Brook, Foudry Brook |

| Status | Largest tributary of outflow river |

The length from near its sources west of Marlborough, Wiltshire down to Woolhampton, Berkshire is a 111.1-hectare (275-acre) biological Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).[1][2] This is primarily from an array of rare plants and animals completely endemic to chalky watercourses.[3]

When Wiltshire had second-tier local authorities, one, Kennet District, took the name of the river.

Course

One of the Kennet's sources is Swallowhead Spring near Silbury Hill in Wiltshire, and others are springs north of Avebury near the small villages of Uffcott and Broad Hinton. These then converge. In these early stages it passes close by many prehistoric sites including Avebury Henge, West Kennet Long Barrow and Silbury Hill. The land drained by the headwaters normally has a deep water table (being in the North Wessex Downs which is mostly chalk as the upper subsoil), thus many stretches are winterbournes when and where precipitation is low and surrounding soils are not so dense with impermeables as to form a surface spring.

The river flows through the towns of Marlborough, Hungerford and Newbury before flowing into the Thames on the reach above Sonning Lock in central Reading, Berkshire.

The Og joins at Marlborough and the Dun enters at Hungerford, followed by the River Lambourn, Enborne and the Foudry Brook. For six miles (10 km) west of Reading's centre, the Kennet, being barraged to maintain its longest heads of water, has a semi-natural secondary channel (a long leat, a corollary), the Holy Brook. This powered the mills belonging Reading Abbey.

Navigation

The Horseshoe Bridge at Kennet Mouth, a timber-clad iron-truss structure, was built in 1891 as a way for horses towing barges along the Thames to cross the Kennet.

Going upstream, the first mile of the river, from Kennet Mouth to the High Bridge in Reading, has been navigable since at least the 13th century, providing wharfage for both the townspeople and Reading Abbey. Originally this short stretch of navigable river was under the control of the Abbey; today, including Blake's Lock, it is administered by the Environment Agency as if it were part of the River Thames.

From High Bridge through to Newbury, the river was made navigable between 1718 and 1723 under the supervision of the engineer John Hore of Newbury. Known as the Kennet Navigation, this stretch of the river is now administered by the Canal & River Trust as part of the Kennet and Avon Canal. Throughout the navigation, stretches of natural river bed alternate with 11 miles (18 km) of artificially created lock cuts, and a series of locks including County, Fobney, Southcote, Burghfield, Garston, Sheffield, Sulhamstead and Tyle Mill overcome a rise of 130 feet (40 m).

Wildlife

The River Kennet is a haven for various plants and animals. Its course takes it through the North Wessex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and the river between Marlborough and Woolhampton is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). The protection that this status affords the Kennet means that many endangered species of plants and animals can be found here. The white drifts of water crowfoot (Ranunculus) in early summer are characteristic of chalk and limestone rivers; there are superb displays by the footbridge at Chilton Foliat, and by the road bridge in Hungerford.

Animal species such as the water vole, grass snake, reed bunting, brown trout, and brook lamprey flourish here, despite being in decline in other parts of the country. Crayfish are very common in parts of the river. However, most, if not all, are now the alien American signal crayfish, having escaped from crayfish farms, which has replaced the native white-clawed crayfish in most southern rivers, although a small population still survives in the River Lambourn. And not forgetting the foundation to supporting this varied wildlife food chain, there are the insects, many hundreds of species, common and rare, that can be found in and around the River Kennet. There are large hatches of mayflies, whose long-tailed, short-lived adults are a favourite food of trout; many species of water beetle and insect larvae. Caddisflies are also very numerous, especially in the late summer. Alongside the river, the reed beds, grasses and other vegetation support many other insect species, including the scarlet tiger moth, poplar hawk moths and privet hawks.[4]

Resource uses

Throughout its history, water mills on the Kennet have been a source of power for various pre-industrial and industrial activities. In places the river has been built up to provide an additional head of water to drive the mills. Three mills remain in Ramsbury alone, and there are many disused or former mill sites, such as at Southcote, Burghfield, Sulhamstead, Aldermaston, Thatcham, Newbury, and Hungerford. Aside from the mills, in the 17th and 18th centuries the river water was also used for the brewing and tanning industries of Ramsbury and Marlborough.[4]

Etymology

The pronunciation (and spelling) was as the Kunnit (or Cunnit).[5] This is likely derived from the Roman settlement in the upper valley floor, Cunetio (in the later large village of Mildenhall). Latin scholars state Cunetio is very unlikely to be a Latin derivation, meaning it is a Celtic British name, like most Roman town names in Britain.[5][6] The frequent Celtic stem "cun-" means "hound", as in the modern Welsh ci, cŵn “dog”.[lower-alpha 1]

Insect kill of July 2013

In July 2013 the Environment Agency investigated an insect kill which resulted when a small quantity (estimated to be two teaspoonfuls (10 millilitres)), of chlorpyrifos, an organophosphate insecticide used in ant poison and available in garden centres, was flushed into the river killing the freshwater shrimp and most other arthropods on the stretch of the river between Marlborough and Hungerford.[7] The dead insects sank to the bottom of the river and rotted, resulting in a bad smell, but no fish seemed to have been killed. However, without insects and shrimps to feed on, many of the fish, birds and amphibians that use the river would be likely to fade away and die.[8] The poison was diluted and removed by the flow of the stream.[9]

See also

- Tributaries of the River Thames

- List of rivers in England

- Locks on the Kennet and Avon Canal

Notes and references

- Notes

- For more details see Wiktionary's Proto-Celtic kū.

- References

- "Designated Sites View: River Kennet". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Map of River Kennet". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "River Kennet citation" (PDF). Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- http://www.riverkennet.org/about_river_kennet.php Archived 16 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Action for the River Kennet website

- Dames, Michael (1976). The Silbury Treasure.

- "Footsteps of the Goddess in Britain and Ireland". Societies of Peace – Second World Congress on Matriarchal Societies. Archived from the original on 20 July 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- "Effects of pollution on River Kennet beginning to come clear". The Wiltshire Gazette and Herald. 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Gerald Isaaman (10 July 2013). "Public health "all clear" given on the River Kennet as the chalk stream continues to suffer". marlboroughnewsonline.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to River Kennet. |

| Next confluence upstream | River Thames | Next confluence downstream |

| River Pang (south) | River Kennet | Berry Brook (north) |