Riverfront Park (Spokane, Washington)

Riverfront Park, branded as Riverfront Spokane, is a public urban park in Downtown Spokane, Washington that is owned and operated by the Spokane Parks & Recreation Department. The 100-acre (40 ha) park is situated along the Spokane River and encompasses the Upper Spokane Falls,[4] which are the second largest[5] urban waterfall in the United States, and, when combined with the Lower Spokane Falls that sit just outside of the park's boundary, create the largest urban waterfall in the country.[6][7]

| Riverfront Park | |

|---|---|

Riverfront Park in 2005 | |

| |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Downtown Spokane, Washington, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 47°39′45″N 117°25′12″W |

| Area | 100 acres (0.40 km2) |

| Opened | May 5, 1978, 43 years ago[1] |

| Operated by | Spokane Parks & Recreation Department[2] |

| Status | Open year round (daily, 5 am to midnight)[3] |

| Public transit access | Spokane Transit Authority |

| Website | my.spokanecity.org/ riverfrontspokane |

Located on the site of a former railyard, visions for creating a park to encompass the Spokane Falls date back as early as 1908,[8] however it would be another 64 years before those visions would be realized. In 1972, the active railyards were removed, and area around the Spokane Falls reclaimed, when construction commenced on an urban renewal project that built a fairground to host the upcoming environmentally-themed Expo '74 World's fair.[8][9][10] Plans called for the site, which hosted the fair from May 4 to November 3, 1974, to be kept as a legacy piece of Expo '74 and converted into an urban park after the fair's conclusion.[8] After several years of work to convert the site, Riverfront Park was officially opened in 1978.[1]

Today, the park sees over 3 million visitors annually[11] and is currently undergoing an extensive five-year redevelopment program which began in 2016.[12] Several of its most recognizable buildings (such as the U.S. Pavilion and First Interstate Center for the Arts) remain from Expo '74 as legacy pieces,[1] and the park is also home to historic features such as the Looff Carrousel[13] and the Great Northern Clocktower.[14]

History

Site history

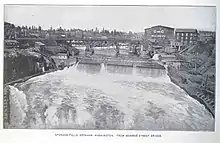

The origins of Riverfront Park are heavily influenced by the initial settling of Spokane on the Spokane Falls along the Spokane River, which was chosen because of the falls' hydropower potential to support a late 19th century city and its economy,[15] and the eventual reaction[16] to the immense amount of industrial and railroad development that engulfed and obscured the area around the falls as Spokane expanded over the ensuing decades.[17]

The site of the park and the surrounding falls were originally inhabited by Native Americans,[18][19] who had a number of fishing camps near the base of the falls,[8] and saw its first American settlers in 1871, who established a claim at Spokane Falls.[15][20] In 1873, James N. Glover, who would become influential in the initial birth and growth of Spokane and considered one of its founders, passed through the region with his business partner Jasper N. Matheney. The two, who recognized the value of the Spokane River and its falls for the purpose of water power[15] and were also aware that the Northern Pacific Railroad Company had received a government charter to build a main line through the area (a line that would eventually become today's Northern Transcon route),[15] proceeded to buy the claims of 160 acres (65 ha) along with the sawmill from the original settlers.[21]

By the late 19th century, much the area along the Spokane Falls had become industrialized with sawmills, flour mills,[22] and hydroelectricity generators.[23] Several residences also began to occupy Havermale Island in the heart of what is now Riverfront Park, however, they were forced to relocate when the Great Northern Railway began to build tracks into downtown Spokane in 1892.[22] In 1902, with the completion of the Great Northern Railway Depot on Havermale Island, trains began running to the city's center[14] and began an era in which railroads would dominate the landscape in Downtown Spokane.

As Spokane continued to grow in the early 20th century, railroading became a major part of Spokane's development and heritage, which led the city to become one of the most important rail centers in the western United States.[24][25] Spokane eventually became the site of four transcontinental railroads, including Great Northern, Northern Pacific, Union Pacific, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad,[26][27] as well as regional ones like Oregon Railway.[28] The presence of railroads within the downtown core was noted by the Olmsted Brothers in 1908 when they began to develop a master plan for parks in the City of Spokane.[8] As the brothers were planning in the Spokane River Gorge, they skipped the area that Riverfront Park now sits on, sarcastically noting that it had already been partially "improved" and hoped that the City of Spokane would eventually come to its senses and reclaim the area around the Spokane Falls for a park.[29]

By 1914, Union Pacific had built their own station on the park's site, along with elevated tracks leading up to it.[17] The heart of Downtown Spokane would become a hub for passenger and freight rail transport and remained that way for several decades.[17] By the mid-20th century, the problems of having a large amount of railroads in the middle of the city were beginning to be realized. The elevated railway, warehouses, and other lines leading into the park severely restricted both physical and visual access to the Spokane River and its falls, leading some locals to compare it to the Great Wall of China.[8] Additionally, the high volume of train traffic created a very noisy downtown,[17] and numerous at-grade railroad crossings were causing traffic congestion issues.[8]

Urban renewal, reclaiming the riverfront, Expo '74, and park creation

In the 1950s, the core of Downtown Spokane began to empty out due to suburbanization,[30] a trend that was prevalent amongst many American cities during this time.[8] This trend sparked urban renewal discussions in Spokane and in 1959, a group called Spokane Unlimited[30] was formed by local business leaders to try and revitalize Downtown Spokane. The group would hire New York-based Ebasco Services to create an urban renewal plan, which would be released in 1961 and called for the removal of the numerous train tracks and trestles in downtown and reclaiming the attractiveness of the Spokane River in the central business district.[8][30]

The plan proposed a timeline that would incrementally renew the area over the next two decades, wrapping up in 1980, and proposed that the effort be funded through bonds, gas-taxes, and urban renewal money from the federal government. One part of the plan, and the first portion to go to voters for approval, would have constructed a new government center.[30] However, efforts to pass bonds to fund the construction were overwhelmingly defeated by Spokane voters over the next couple years,[30] and by 1963, Spokane Unlimited had to revise its vision.[8] They hired King Cole,[31] who had recently worked on some urban renewal projects in California, to execute EBASCO's urban renewal plans in Spokane.[32] In light of the failed votes, Cole formed a grassroots citizen group, called the Associations for a Better Community (ABC), to build community support through the 1960s around the idea of beautifying the riverfront and turning Havermale Island into a park.[8]

With support around beautification growing, Spokane Unlimited would go on to commission a feasibility study in 1970 for using a marquee event, proposed to be in 1973 to celebrate the centennial of Spokane, to fund the beautification. However the report stated that a local event would not have the stature to bring in enough funding for the group's beautification aspirations, and that it needed to go bigger; it suggested that Spokane host an international exposition that could bring in state and federal dollars, as well as tourists from outside Spokane, to fund a riverfront transformation. The idea to host an caught on—inquiries were made to the Bureau of International Expositions as well as an additional study that was commissioned in the fall of 1970, and results both came back very positive. The 1974 world expo was identified as the target event.[8]

Efforts to host the expo just three-and-a-half years later began immediately and was a tall order considering that Spokane would be the smallest city at the time to ever host a World's fair, and that the proposed site had 16 owners, including the railroads. Funding came from local, state, and federal sources, including a new business and occupation tax that the Spokane City Council passed in September 1971 after a ballot bond measure to provide local funding failed the month prior.[8] The event was officially recognized by then-President Richard Nixon in October 1971, and the following month, the Bureau of International Expositions gave their sign-off[35] on the event as well.[8]

With approvals and funding falling in place, one last challenge was transforming the site and removing the railroads. Through intense negotiations, the Expo '74 planners, including King Cole were miraculously able to convince the railroads to agree to a land swap and donate the land needed for the Expo site.[8][31][32][36] The railroads were consolidated onto the Northern Pacific Railway lines further to the south in Downtown Spokane,[25] freeing up the site for construction to transform it to host the environmentally-themed Expo '74. Demolition began in 1972,[8][9][10][33] and the fair was held from May to November 1974, welcoming nearly 5.6 million attendees.[37]

After the world's fair concluded, the site was converted into Riverfront Park;[8] it was dedicated in 1978 by President Jimmy Carter in a ceremony on May 5 that was attended by roughly 50,000.[1][38][39]

2016–2021 redevelopment

Riverfront Park had remained largely unchanged and had not seen any major investments since its conversion to a park after Expo '74 and many of its physical facilities were beginning to show their age and disrepair.[40][41] In 2012, with a vision to reinvigorate Riverfront Park for the next generation, the Spokane Park Board approved the beginnings of an updated master plan for the park. This first phase of the new master plan would outline general concepts only, but in June 2013, details and estimated costs began to be developed by 20-member advisory committee. Aspirations for the park's future included using it as a key fixture in Downtown Spokane to draw more people to the center of the city, boosting the number of events in the park, creating sustainable revenue, increasing viewing opportunities to the Spokane River, and also protecting natural resources and habitat around the park.[42]

The new master plan would be completed by early summer 2014, and put toward the Spokane City Council for adoption that summer with the goal of putting it on the general election ballot for a public vote later that year.[42] In November 2014, Spokane voters passed a $64.3 million bond to redevelop Riverfront Park. The bond measure was approved by 67 percent of votes, having required 60 percent to pass.[43][44] Passage of the bond measure, called Proposition No. 2 did not raise taxes on citizens as it effectively replaced another parks special property tax that was set to expire. The new bonds raised to pay for the park's redevelopment are set to mature in 2035.[45]

Several key projects of the bond measure were a renovation of the U.S. Pavilion, construction of a new skate ribbon to replace the former Ice Palace that was hosted each winter at the Pavilion, construction of a new building for the historic Looff Carousel, and construction of new public spaces such as the Howard Street Promenade.[46]

Construction on the phased, five-year long project began in 2016 with a ground breaking ceremony on July 8 at the site of the future Numerica Skate Ribbon.[12] As of 2020, construction on the redevelopment continues and is expected to wrap up by early 2021. Additional city projects adjacent to the park will also be complete by the end of 2021, including a reconstruction of the Post Street Bridge that form's the park's western boundary and the construction of the Spokane Sportsplex along the park's northern boundary.[47]

Location and overview

Geography

Riverfront Park is located just north of the Downtown Spokane core, in Spokane's Riverside neighborhood, and is generally bounded by Spokane Falls Boulevard to the south, Post Street to the west, the northern banks of the Spokane River, and Division Street to the east.[48] Portions of its North Bank Area extend farther north from the river, bounded by Howard Street to the west, Cataldo Avenue to the north, and Washington Street to the east.[49] A majority of the park's elevation ranges from 1,880 feet (570 m) to 1,890 feet (580 m) above sea level, placing it more or less level with the surrounding Downtown Spokane, however, the elevation varies as one moves onto the park's two islands and closer to the Spokane River.[50][51]

The Spokane River, the park's namesake and main natural attraction, flows from east to west through the park, beginning as a single run, and eventually splitting up across three channels, creating the two main islands featured in the park.[48] The first split into a northern and southern channel creates Havermale Island, the larger of the two islands.[52] Further downstream, at around the midpoint of Havermale Island, the northern channel splits again into the north and mid channels, creating snxw meneɂ, formerly known as Canada Island.[53][54] These northern two channels contain the Upper Spokane Falls, surrounding snxw meneɂ. All three channels converge back into a single run just downstream of the Upper Falls.[48]

Areas

Riverfront Park can be described through several unofficial, general areas: the South Channel area, Havermale Island, and North Bank area. The South Channel[55] area of the park is located along the southern branch of the Spokane River after its initial split, along Spokane Falls Boulevard, and contains several of the park's features including the Looff Carrousel, Numerica Skate Ribbon, and Rotary Fountain.[56][57] The area also serves as the South Gateway to Riverfront Park.[58] Moving northward across the South Channel is Havermale Island which encompasses a number of grassy meadows, natural conservation areas, amphitheaters, the U.S. Pavilion, and the Great Northern Clock Tower.[59][60][61][62] The northern area of Riverfront Park, just across the Spokane Falls from Havermale Island, is generally referred to as the North Bank area[63][64] and contains the park's northern gateway.[65] Up until Riverfront Park's current redevelopment, much of the North Bank area was underdeveloped as a park and primarily used for parking and park maintenance facilities.[58] As of 2020,[66] much of the North Bank area is currently under construction to build a thematic playground and Sportsplex.[67][68]

Urban context and connectivity

Riverfront Park's location in Downtown Spokane creates a highly urban context for the park. The park's southern boundary of Spokane Falls Boulevard along the downtown core creates a distinct urban streetwall, or park-city edge,[69][70] similar to edges that exist in other urban parks such as Grant and Millenium Parks in Chicago,[71] the National Mall in Washington, D.C.,[72] and Central Park in New York City.[73] Zoning regulations along this southern edge have been recently debated, pitting developers' concerns that height restrictions are hindering development against concerns that increased building heights along Spokane Falls Boulevard would cast undesirable shadows onto the park below.[74]

The park is also well connected to the urban areas and destinations that surround all sides. The park's southern and western boundaries consist entirely of roadways, which are lined with sidewalks that open directly onto adjacent plazas and lawns within Riverfront Park.[75][76][77] Further east, the First Interstate Center for the Arts, and Spokane Convention Center physically occupy a large amount of park's frontage, however, access between Downtown and the park, and even access from the buildings themselves, is integrated into the architectural design of those facilities through large breezeways, terraces and door openings.[78][79][80] Along the northern boundary of the park, the natural topography of the Spokane River's banks, combined with private development that lines much of that side of the river, makes access slightly more limited. Despite this, access points to the park are still frequently available through trails that parallel the river and intersect with roadways and connect with the parking lots of these private developments along the way.[81]

A number of paths and roadways also traverse the park, providing further connectivity to surrounding areas beyond. From the east, the Spokane River Centennial Trail continues its run from the adjacent University District and WSU Health Sciences Spokane campus, entering Riverfront Park from underneath the Division Street Bridge. As it meanders westward through the park, it passes by many of the park's features including the Spokane Convention Center, First Interstate Center for the Arts, Red Wagon, Looff Carrousel, Rotary Fountain, and the Numerica SkyRide and Skate Ribbon. The trail exits the west end of the park via the Post Street Bridge, continuing on underneath the Monroe Street Bridge toward Kendall Yards, and eventually, Riverside State Park.[82][48]

In the north—south direction, the recently completed Howard Street Promenade provides a direct link between the core of Downtown Spokane and the North Bank areas of downtown. The promenade runs from the Rotary Fountain on the park's southern boundary, across snxw meneɂ, and ends at the park's northern entrance across the street from the Spokane Veterans Memorial Arena.[58] Prior to the completion of the promenade, it was still possible to pass through the park in a north—south manner, but the route was much more circuitous and did not offer a direct link (neither physically or visually) between the two ends of the park.[83] Other major north—south paths through the park include pedestrian suspension bridges over the Upper Spokane Falls toward the west end of the park, pedestrian bridges near the east end that connect the First Interstate Center for the Arts with a hotel on the north bank of the river, and the Washington Street Bridge which carries cars and pedestrians through the center of the park.[48]

Features and attractions

Natural attractions and open space

The Spokane River and Spokane Falls are the main natural attraction of Riverfront Park and are visible from many areas of the park. Along the river's calm south channel, many of the walking paths and lawns go right up to the river's edge, allowing park-goers to get close to the water. People have been known to stick their feet in the water[84] and fish in the south channel from time to time.[85][86][87] Access and visibility to the river's north channel, which is home to the falls, is generally more limited due to the faster and rougher water and river gorge that is created by the falls. However, many official viewing points exist, most notably two pedestrian suspension bridges at the west end of snxw meneɂ that provide up-close viewing of the falls.[88]

In several areas, such as the conservation area at the site of the former YMCA building, walkways also run right alongside the falls.[89]

Riverfront Park also features a number of open grassy meadows[90] on the south side of Havermale Island facing the calmer south channel of the Spokane River,[91][48] including the Lilac Bowl, which is a natural amphitheater,[60] and the Clock Tower Meadow, adjacent to the Great Northern Clocktower.[92]

Structures and built attractions

Riverfront Park is also known for its built attractions. Two of Riverfront Park's structures, the U.S. Pavilion and Great Northern Clocktower, are a couple of Spokane's most recognizable landmarks and have been featured prominently in the logo of Riverfront Park for a number of years. While prior versions of the park's logos depicted the two landmarks more literally,[93][94] the park's latest logo, released in 2017, features abstractions of the landmarks' forms. The logo evokes triangular-shaped form of the pavilion along with its arc-shaped bottom structural component and leaning posture. The thin, rectangular shape and triangular top of the clocktower, along with its round clock faces are also abstracted into the design. Other geometric aspects of the logo are inspired by cable-work of the Pavilion's structure, Spokane's street grid, and the crossing of many paths.[95]

U.S. Pavilion

The U.S. Pavilion, officially named the U.S. Federal Pavilion,[96] and also referred to as the Pavilion at Riverfront, or simply the Pavilion, is a steel and cable structure located in the center of Riverfront Park on Havermale Island.[97] The Pavilion, which is one of the legacy pieces of Expo '74[98] and served as the pavilion for the United States during the event,[99] is used today as an event center, with indoor and outdoor event spaces, an amphitheater, raised catwalks, and viewing platforms.[100] When not in use, the Pavilion function as open public space, providing views to the Spokane River.[101]

History

The City of Spokane was extended federal recognition of the environmentally-themed Expo '74 by then-US President Richard Nixon on October 15, 1971. Soon after, the U.S. Department of Commerce issued a proposal for federal participation in the event. It recommended that the president would find the national interest of the United States served by its participation. It stated that the theme of the fair was of great national importance and interest, and that participation would help provide a platform to showcase the country's accomplishments in the environmental field on a world stage. Besides having a platform to increase awareness to the world about the dangers of environmental damage and initiatives taken to counter it, participation in the exposition would also yield economic to the United States, including bringing foreign travelers and giving American manufacturers an opportunity to showcase their anti-pollution equipment that could create new overseas trade opportunities for the United States.[102]

It was proposed that the best way for the United States to participate in the exposition be through an exhibit to be housed within a pavilion that would be constructed by the U.S. government. Additionally, in order to ensure a good cost-benefit to the United States government, it was recommended that the pavilion be designed to be permanent and remain after the fair for residual use by the Department of the Interior, as a component of the civic center and urban park (that would become Riverfront Park) that would be left over as a legacy site after Expo '74 concluded. A four-acre plot of land within the Expo '74 site would be deeded by the City of Spokane to the United States Government for the Pavilion.[103] Prior to the transformation of the larger 100-acre Expo site, a Travelodge motel, built in 1959, sat on the land that would become the U.S. Pavilion.[97]

To prepare for the design and construction of the Pavilion, the Department of Commerce issued a request for proposal in December 1971[104] from firms across the country for preliminary design concepts. Twenty firms initially responded to the proposal, of which half were chosen to advance in the competition. Three finalists were eventually named, with Los Angeles-based Herb Rosenthal & Associates being awarded the contract to develop the plan, including schematic concepts and cost estimates. The firm partnered with the Portland, Oregon office of Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill as well as Spokane-based Trogdon-Smith,[103] a firm that would later merge with other firms and eventually become NAC Architecture.[105]

In January 1973, after unsuccessful negotiations with Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, who was already on the design team, a contract for the pavilion's final design was awarded to Seattle-based architecture firm Naramore, Bain, Brady & Johanson, now known as NBBJ.[104][98] The final design differed slightly from the earlier conceptual designs, but still retained a lot of the original elements including soft canopy covering a courtyard, theater, holding area, and permanent building.[104] The Pavilion was formed to look like a giant tent (and was originally covered) as a way to support the fair's environmental theme and was the largest structure at the fair.[106] In 1972, the United States Congress provided $11.5 million ($70.5 million in 2019 dollars) to build the pavilion and outfit it with exhibits.[107]

To help ensure a successful construction project and on-time delivery, the construction of the project was managed and administered by the General Services Administration rather than the Commerce Department. The Commerce Department was short-staffed and experiencing a heavy workload at the time, and its base in Washington DC was considered too remote to Spokane to run the construction successfully. It subsequently entered an agreement with the GSA, which leveraged its Pacific Northwest connections at the GSA regional office in Auburn, Washington.[108] The GSA's agreement with the Department of Commerce called for the project to utilize a construction management technique, and by mid-December 1972, the GSA began the process of selecting a construction management firm through an invitation-to-bid process, eventually selecting California-based Rhodes-Schmidt as the low bidder.[108] Due to time constraints, the GSA decided to use a phased-bid project delivery method so that as soon as the architects completed a portion of the design, it could be put out to bid for construction.[108] The first construction contract was awarded on April 25, 1973 for earthwork, foundation components, and underground utilities, and a groundbreaking ceremony was held just six days later on May 1, 1973[108] in a ceremony attended by a number of distinguished guests including federal officials, local and Expo '74 officials, and foreign dignitaries representing nations including the USSR.[98]

The Pavilion's tower stands 150 feet tall, and the structure contains roughly 4.6 miles of cabling.[107]

As part of its original design, the Pavilion featured a vinyl covering that was installed in 1973. The covering, which cost $1 million and weighed 12 tons, was not meant to last,[106] and was removed in early 1979.[107] The Pavilion has had its iconic skeleton-look with exposed cabling ever since.

Renovation

The Pavilion recently underwent a full renovation as part of Riverfront Park's redevelopment.[109] As part of the project, the IMAX theater was removed along with a number of other structures that had been added to the pavilion since its original construction.[110] The renovated pavilion reopened on September 6, 2019 and features an open floorspace for events combined sloped and terraced landscaping to provide seating areas for audiences. One "indoor space" from the pavillion before redevelopment remains incorporated into the redesign to be used as a ticketed entry point when needed, and also features rental space and park offices. Additionally a 40-foot high platform was constructed in its center to provide views of the Spokane River. There was debate about recovering the pavilion's structure like it was during Expo '74, but concerns about budget and schedule made it unfeasible. Instead, several dozen panels mounted on the west side of the cable structure create shade for portions of the renovated pavilion's floor and seating areas.[111]

The redesign also added plexiglass "blades" illuminated by LEDs to the cables that make up the Pavilion. The redesign team wanted to highlight the Pavilion at night in a way that would incorporate and enhance the unique look of the net-like canopy.[112] There are 476 blades that measure 3', 4', and 6' in length but are controllable in six inch segments.[113] The U.S. Pavilion currently offers animated light shows from Dusk-10pm on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays and specialized light shows or static looks created for holidays and special events.[114]

In August 2020, the lighting design for the Pavilion won awards for Outdoor Lighting Design and Control Innovation from Illuminating Engineering Society.[115]

Great Northern Railway Clocktower

The Great Northern Railway Clocktower is located on Havermale Island and was originally constructed in 1902.[116] It was part of the Great Northern Railway Depot that existed on the Riverfront Park site prior to Expo '74. When the rail tracks were removed and site transformed in preparations for Expo, the depot was demolished in 1973, but the clock tower was left standing after a public push to save it and has now become a Spokane icon, reminding people of the role that railroading played in the development of Spokane.[117] The location roofline of the former depot can be seen on the face of the tower where the sandstone masonry blocks change color.[116]

The tower stands at 155 feet and 6 inches tall, and features a nine-foot diameter clock face on all four of its sides. The clock itself is controlled by a solid, 700-pound brass pendulum that needs to be hand-cranked every week by park staff. While the clock chimes every hour, it has never had bells in its entire history. Even when it was first built, it had electronic speakers that replicated chime tones.[116]

Looff Carrousel

Riverfront Park is home to one of the many carousels built by prominent late 19th and early 20th century hand-carved carousel builder Charles I. D. Looff, who is notable for building the first carousel at Coney Island and one of the piers that make up the Santa Monica Pier. Spokane's carousel, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977,[118] and still operates for riders today, was built in 1909 as a wedding gift from Looff to his daughter Emma and her husband Louis Vogel.[119][120] The ride was first installed in nearby Natatorium Park, and operated there until the park's closure in 1968. When Expo '74 came, organizers originally wanted to bring the carousel out of storage and showcase it to the world during the event, however it was deemed impractical due to the restoration and moving costs. It would not be until 1975, after the conclusion of Expo '74, that the ride would be installed on the expo's legacy site that is now Riverfront Park. The building that housed the German Hofbrau during world's fair became the new home for the Carousel,[1][120] and it operated in there until 2016[119] when the ride temporarily closed for Riverfront Park's recent redevelopment.

During the redevelopment, the carousel was stored and refurbished while the former German Hofbrau building that housed it was demolished and replaced. A new building was constructed in its place on the same site and opened on May 12, 2018.[121]

Numerica SkyRide

The Numerica SkyRide is a gondola lift ride located at the southeast corner of Riverfront Park that takes people westward from park, past Spokane City Hall and over Huntington Park, descending down into the Spokane River gorge to view the Lower Spokane Falls. The ride crosses the river, making a loop back toward Riverfront Park after passing beneath the Monroe Street Bridge.[122]

The current iteration of the ride was constructed in 2005 by the Doppelmayr Garaventa Group.[123] However the original version of the SkyRide was built in the 1960s by Riblet Tramway Company[123] and purchased by the City of Spokane secondhand for Expo '74.[124] The ride had two routes at Expo, one over the exposition's fairgrounds, and the other descending down the Spokane River Gorge to view the Spokane Falls. The fairgrounds route was removed after the conclusion of Expo, but the Falls route was retained.[98] The original ride had open-air gondolas served until the ride's reconstruction in 2005, which rebuilt the attraction and upgraded it with fully enclosed gondolas as part of a $2.5 million project. Refurbishment to the original ride was considered, but ultimately the decision was made to replace the entire system and its parts.[124]

Its naming rights were acquired in February 2019 by Numerica Credit Union for a ten-year term along with the adjacent Numerica Skate Ribbon.[125]

Numerica Skate Ribbon

The Numerica Skate Ribbon, originally known as the Riverfront Skate Ribbon, opened in 2017 as part of Riverfront Park's redevelopment.[126] The venue is located at the southwest corner of the park, across from River Park Square and Spokane City Hall.[127] The ribbon primarily as a year-round skating venue, with hard surface skating accommodated in the warmer months[128] and ice skating offered in the winter months. The facility also has a cafe and hosts other events throughout the year on its concrete surface, such as art walks,[129] beer gardens, weddings, and other events.[69]

The ribbon was constructed to replace the seasonal Ice Palace ice skating rink feature that Riverfront Park set up annually under the U.S. Pavilion.[130] During its planning and design stages, the design and format of the ribbon, which features a 715-foot meandering and sloped path as well as an ice pond, drew criticism from certain user groups for its contrast to the flat and open ice rink format of the former Ice Palace. The new format meant that the ribbon would no longer be able to accommodate hockey players and ice skating instructors with large classes for the same purposes as before.[69]

In February 2019, Numerica Credit Union acquired the naming rights for the Skate Ribbon along with the adjacent SkyRide. The $90,000 a year deal runs through early 2029, with an option to extend another 10 years.[125] The revenue will be used to support programming and maintenance at the park.[131]

Red Wagon

The Red Wagon, officially named The Childhood Express, is a play sculpture that is modeled after a Radio Flyer wagon. The sculpture was commissioned by the Junior League, with donations from its Spokane chapter and other local business, for Washington State's Centennial celebration (the state achieved statehood in 1889) and was dedicated to Spokane's children on August 18, 1990.[132]

Sculpted by local Spokane sculptor Ken Spiering, the feature stands 12 feet (3.7 m) high, spans 27 feet (8.2 m) long,[133][134] and weighs 26 tons from its steel and concrete structure.[135]

Users can enter and exit the wagon through a staircase located at the underside of its rear end, taking them up to a wooden platform "within" the wagon. The platform covers the entire extents of the wagon, allowing users to walk right up to the edge of the wagon where its "walls" double as guardrails. At the front end, the wagon's handle doubles as a playground slide, providing another way for users to exit and interact with the sculpture.[135]

The Childhood Express is located along Spokane Falls Boulevard on Riverfront Park's southern boundary, between the First Interstate Center for the Arts and the Looff Carousel, and diagonally across from the Davenport Grand Hotel[136]

Art

Riverfront Park features a large quantity of art installations scattered across its landscape, which make up approximately half of the nearly three dozen sculptures installed within the Downtown Spokane area.[137] Sculptures have been added over the years from a broad spectrum of artists and artistic styles ranging from abstract forms, to lifelike statues, and whimsical sculptures. The pieces also represent a broad range of purposes from a memorial to the Vietnam War, to memorials for local icons such as astronaut Michael P. Anderson, who was killed in the Space Shuttle Columbia Disaster, to pieces honoring the local Native American heritage, as well as interactive play sculptures, among others.[138]

The late-local artist Harold Balazs has a number of pieces installed throughout the park, most notably the Centennial Sculpture, which is an abstract aluminum sculpture floating in the Spokane River, and the Rotary Fountain.[139]

Garbage Goat

One of the park's most popular[140] installations is Goat,[137] a sculpture that was installed in 1974 as part of the art for Expo '74.[141] Commonly referred to as the "Garbage Goat" or the "Garbage Eating Goat", the sculpture is located just east of the Looff Carousel along the southern edge of Riverfront Park.[137] Going along with Expo '74's environmental theme, the sculpture was created as an interactive art piece that doubles as a unique trash collector. Its creation and installation was sponsored by the Spokane Women's Council of Realtors and sculpted by Sister Paula Mary Turnbull, a local nun and leading figure in Inland Northwest arts.[140] As its name suggests, the corten steel[137] sculpture was modeled after a goat and features a vacuum mechanism that sucks up small pieces of garbage through its mouth, allowing users to "feed" it.[141]

In an ironic juxtaposition for the environmentally-themed fair, the art piece was heavily debated before it was even installed, with dairy goat farmers protesting that the creation of the whimsical piece perpetuated the stereotype that goats are reputed to eat anything; they stressed that the public be educated that goats needed to be fed properly like any other animal.[140][141] A compromise was eventually reached between the farmers and the Expo '74 organizers, which saw the installation of the garbage eating goat sculpture in exchange for real-life dairy goats at the fair getting signage installed that touted their milk production capabilities if fed a proper diet of the “finest of hays and grains”.[141]

Over the years, the goat has developed a cult following across generations of Spokanite parents and children.[141] The goat has an unofficial Facebook page with thousands of followers[142] and the Spokane County Regional Solid Waste System has its public educational outreach blog named after it.[143][144] For its 40th birthday, the City of Spokane put on a celebration of the goat, "feeding" it a slice of birthday cake, and holding a goat-themed party for the public in its honor, which featured beer from a local brewery called Iron Goat Brewing that was sold by the pint at prices found in 1974, the year of the sculpture's creation.[145]

Future

- A Shane's Inspiration playground (yet to be named) broke ground in Fall 2019[146] on the park's south end, near the Upper Falls Power Plant and is scheduled to be open in the fall of 2020.[147] The project is not part of Riverfront Park's redevelopment bond, rather, it was funded by donors, including a $1 million donation from Providence Health & Services.[146] Shane's Inspiration focuses on designing playgrounds that are all-inclusive and accessible to all children, including those with physical or developmental disabilities, and Riverfront Park's will be the first of its kind in Spokane.[147] The playground will total 13,000 to 14,000 square feet, including 5,800 square feet that will be designed as a sensory playground.[146][147]

Former

Prior to its redevelopment, Riverfront Park hosted the following features:

- The Ice Palace was a seasonal ice skating rink that was set up underneath the U.S. Pavilion. It originally opened in 1977 until its closure in 2017,[148] and was replaced by the permanent Numerica Skating Ribbon during Riverfront Park's redevelopment.[130]

- The IMAX Theater was part of the U.S. Pavilion complex and originally opened in 1978.[149] It reached peak attendance in 2005, but attendance began to wane after the opening of an IMAX facility at the nearby AMC theater at River Park Square and a loss of licensing to show big-budget Hollywood films.[150] The decision was made in 2016 to permanently close the theater and it would be demolished in early 2018 as part of the U.S. Pavilion renovation project in Riverfront Park's redevelopment.[150]

- The Pavilion Rides were a collection of amusement rides owned by the City of Spokane that were set up each summer under the U.S. Pavilion. The rides did not fit in with the new vision of Pavilion after its redevelopment and were identified by the 2014 master plan to be removed.[151] A new location to host the rides was considered on the redeveloped North Bank, but the proposal was ultimately voted down by the Spokane Park Board in September 2018, and several of the rides were auctioned off.[152]

Hydropower

Early history

.jpeg.webp)

The fast-moving Spokane River and Spokane Falls within and around Riverfront Park has been harnessed for its hydropower ever since the area began to be settled in the 1870s[153] when flumes and waterwheels were used to mechanically drive sawmills and flour mills located along the river.[154] On September 2, 1885, hydroelectricity would be used to power Spokane (then-named Spokane Falls) for the first time, illuminating only 10 to 11 arc lights in the downtown business district, when George A. Fitch installed a secondhand Brush electric arc dynamo generator, dismantled from the SS Columbia steamship, in the basement of the C & C Flour Mill located along the river.[153][154][23]

As the demand for electricity increased, Fitch was bought out the following year by a group of local businessmen who formed the Spokane Falls Electric Light and Power Company.[153][154] The group purchased acquired 1,200 incandescent bulbs from Thomas Edison's company and, as part of the purchase agreement, agreed to only use Edison-patented equipment to power them.[23] A 30-kW plant from Edison was soon purchased and installed it on the Spokane River's North Channel along the Post Street Bridge,[153][154][23] which today forms the western boundary of Riverfront Park, and powered among other things, the city's first opera.[154] The company, looking to expand, would seek an investment from the Edison Illuminating Company in New York, and would rebrand as the Edison Electric Illuminating Co. of Spokane Falls (EEICSF),[153][154] headquartering in Downtown Spokane at the southwest corner of Sprague Avenue and Howard Street.[23]

By the late 1880s, demand for electricity in the young city was skyrocketing, including 24-hour electric service in the wealthy Browne's Addition neighborhood.[23] This led the EEICSF to expand, installing a new generator at their plant that increased its generating capacity by four times,[153][23] and also sparked the formation of two competing power companies — the Spokane Falls Water Power Co. in 1887 and Washington Water Power (now known as Avista Utilities) in 1889.[23][155] However, around this time, attaining financing to further the expansion of hydroelectricity also began to prove difficult, especially for EEICSF and its east coast-based investors.[23] Many, including Edison himself, began to favor the output consistency of steam power, which was not dependent on the highly-variable flow of a river, as the future of electricity generation.[153][154]

Despite the market-shift, entrepreneurs at the newly established companies continued to forge ahead in their investment with hydroelectric power generation. Washington Water Power was in the process of installing a generator on the Lower Spokane Falls, just outside of today's Riverfront Park, when Spokane's Great Fire struck in August 1889.[154] After the fire and rebuilding of the city, demand for electricity grew so rapidly that Washington Water Power moved ahead with plans for an even larger power generating facility on the Lower Falls and constructed an 18-foot tall rock-crib dam[154] made of timber,[155] to raise the water levels behind its Lower Falls generator.[153] The construction of the dam, along with a new powerhouse, collectively became known as the Monroe Street Power Station and was completed on November 12, 1890.[154] The enormous generating capacity of the new facility began an era of dominance for Washington Water Power over the other companies that operated smaller generators in the vicinity.[154] Washington Water Power would gradually begin to purchase portions of the EEISCF, taking a controlling stake in their competitor by 1891,[153][154][156] and also acquire other companies that would eventually be unified under the Washington Water Power Company name.[153] The dynamos of the other companies would be consolidated into the Monroe Street Power Station, which grew its generating capacity to 894 kilowatts, which was eventually expanded to 1,439 kilowatts by 1892.[154]

Modern history

In 1922, Washington Water Power would construct an additional dam, known as the Upper Falls Diversion Dam, at the eastern tip of Havermale Island, spanning across the North Channel of the Spokane River, just over the Upper Spokane Falls.[154] The dam would divert water through the river's South Channel to a 10 MW[157] generator at the Upper Falls Power Plant, also built in 1922.[158]

Washington Water Power's timber Monroe Street Dam at the Lower Spokane Falls would be damaged in a high water event and eventually be replaced with a concrete gravity dam[159] in the same location just a few hundred feet west of what would become Riverfront Park.[160] The reconstruction of the dam was completed just before Expo '74 and included the construction of Huntington Park, immediately adjacent to present-day Riverfront Park, that allowed visitors to see water fed into to the plant's turbines.[155][161] In 1992,[159] a project at the Monroe Street Power Station replaced its original powerhouse with an underground one, further expanding Huntington Park by creating a new plaza over the underground powerhouse. The project also replaced its original, century-old 1890 generator (which would be donated to the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan for permanent[162] display)[163] with the station's current 15-MW generator.[159]

Legacy

.jpg.webp)

The impacts of hydroelectricity generation on the Spokane Falls throughout Spokane's history remains visible in Riverfront Park today and plays a major role in its attractions. The adjacent Huntington Park, Lower Spokane Falls, and Monroe Street Power Station are the primary sightseeing features of Riverfront Park's Numerica SkyRide.[164] Additionally, a 2014 project[161] that renovated the Avista Utilities-owned Huntington Park at the Lower Falls, added a new plaza in front of Spokane City Hall that creates an unofficial extension of Riverfront Park, effectively bridging the two parks together.[162] Hydroelectric power generation on the Upper Spokane Falls has also shaped Riverfront Park's features. In addition to the Upper Falls Power Plant being listed as an official Riverfront Park sightseeing attraction,[165] the construction of the Upper Falls Diversion Dam created the calm waters of Riverfront Park's South Channel, which are home to a number of the park's attractions including the Looff Carousel, Red Wagon, First Interstate Center for the Arts, and Howard Street South Channel Bridge. The calm water enables many of these attractions, including the steps and floating stage[166][167] at the First Interstate Center, as well as the lowered viewing platforms on the South Channel Bridge[168] allow visitors to interact with the river.

Festivals and events

Every year, Riverfront Park plays host to a number of prominent Spokane events including:

- The annual Lilac Bloomsday Run, held in May, uses Riverfront Park as the site of its official post-race activities.[169]

- Spokane Hoopfest, held annually in June, uses Riverfront Park for exhibitors and vendors[170] and its Nike Center Court[171]

- The 4th of July annual carnival and fireworks display.[172]

- The Royal Fireworks Concert, an annual concert ending in Handel's Music for Royal Fireworks and a corresponding fireworks display.[173]

- Gathering at the Falls Powwow, an annual celebration held in summer that celebrates the living culture of native people.[174]

- Pig Out in the Park, an annual food and music festival hosted in the park during Labor Day weekend.[175]

References

- Geranios, Nicholas (August 10, 2008). "A look at the history and future of Spokane's Riverfront Park". Seattle Times. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Park Finder". City of Spokane, Washington - Parks and Recreation. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Visitor Information". City of Spokane. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Butler, Marv (March 6, 1979). "Pavilion still focal point". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (aerial photo). p. 1.

- "Upper Spokane Falls". Outdoor Project. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Hickman, Matt. "9 unforgettable urban waterfalls". Mother Nature Network. Narrative Content Group. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Getting on the Trail - Downtown: Miles 20 -23". Spokane Centennial Trail. Visit Spokane. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Kershner, Jim. "Expo '74: Spokane World's Fair". HistoryLink.org Essay 10791. HistoryLink.org Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "Expo '74 Plaque". Downtown Spokane Heritage Walk. City of Spokane.

- "From the Archives: Building of Expo '74". The Spokesman-Review. May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "About Us". City of Spokane, Washington. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Loukides, Kaitlin (July 8, 2016). "Groundbreaking starts for redesign of Riverfront Park". KREM-TV. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Looff Carrousel". City of Spokane. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "The 1900s: Dawn of a New Century". Riverfront Park History. City - County of Spokane Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Kensel, W.H. (Spring 1971). "Spokane: The First Decade" (PDF). Idaho Yesterdays. Boise, Idaho: Idaho State Historical Society. 15 (1): 19.

- "Rediscovering the River". Spokane Historical. Eastern Washington University. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "History". Riverfront Park: A Journey through the Decades. 2017 Mid-Century Survey Listed Properties Historic Properties Map Check out our Facebook Page! Historic Spokane Heritage Tours Contact Us! Search City - County of Spokane Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Hanson, Clayton. "The Creation of the Falls: The Indian Falls". Spokane Historical. Eastern Washington University. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Ruby, Robert H.; Brown, John Arthur (1988). Indians of the Pacific Northwest: A History. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8061-2113-0.

- Wilma, David (January 27, 2003). "J. J. Downing and S. R. Scranton file claims and build a sawmill at Spokane Falls in May 1871". Essay 5132. HistoryLink. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- Schmeltzer, Michael (1988). Spokane: The City and The People. Helena, Montana: American Geographic Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-938314-53-0.

- "The 1890s: A Burgeoning City". Riverfront Park History. City - County of Spokane Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "1880s". Spokane Electric. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Spokane History". Downtown Spokane Heritage Walk. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Tinsley, Jesse (May 18, 2020). "Then and Now: Transcontinental railroads". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Schmeltzer, Michael (1988). Spokane: The City and The People. American Geographic Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 0-938314-53-X.

- Stratton, David H (2005). Spokane and the Inland Empire: An Interior Pacific Northwest Anthology. Pullman, Washington: Washington State University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-87422-277-7.

- Rydell, Robert W.; Youngs, J. William T. (2001–2006). "The Fair and the Falls: Spokane's Expo '74: Transforming an American Environment". The Journal of American History. 88 (1): 302. doi:10.2307/2675068. ISSN 0021-8723. JSTOR 2675068.

- Kershner, Jim. "Olmsted Parks in Spokane". HistoryLink.org Essay 8218. HistoryLink.org. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Deshais, Nicholas (November 23, 2017). "Before Expo was Ebasco, the plan to save downtown Spokane". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Rebecca, Nappi (December 20, 2010). "King Cole, 'father' of Expo '74, dies". Seattle Times. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Carpenter, Cory. "The Father of the Fair". Spokane Historical. Eastern Washington University. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Demolition works starts on section of GN Depot". Spokesman-Review. August 4, 1972. p. 1.

- "Clock Tower". Downtown Spokane Heritage Walk. City of Spokane. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "1974 Spokane - The Expo". Bureau Internationl des Expositions. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- "The 1970s: The World Visits Spokane". Riverfront Park History. City - County of Spokane Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "1974 Spokane - At a Glance". Bureau International des Expositions. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Floyd, Doug (May 5, 1978). "Carter lauds Spokane's effort". Spokane Daily Chronicle. p. 1.

- Roberts, Jack (May 6, 1978). "President 'thrilled' by Spokane visit". Spokesman-Review. p. 1.

- "Downtown Spokane Brownfields Walking Tour" (PDF). City of Spokane and Washington Department of Ecology. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Riverfront Park Master Plan 2014" (PDF). Parks & Recreation Planning. Spokane Park Board. p. 28. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Spitzer, Judith (June 5, 2014). "Riverfront Park plan, financing are up for vote". Spokane Journal of Business. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Walters, Daniel (September 5, 2019). "Beloved icon, neglected eyesore and main battleground over the park's rehab project: The U.S. Pavilion reopens as a new symbol of innovation". The Inlander. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Deshais, Nicholas (November 5, 2014). "Spokane voters willing to pay to fix streets, park". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Cargill, Chris; Walter, Allison. "Citizens' Guide to Spokane Streets Levy & Park Bond". Washington Policy Center. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Five Major Elements". City of Spokane, Washington. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- "Redevelopment Timeline" (PDF). Riverfront Spokane. City of Spokane. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Google. "Riverfront Spokane" (Map). Google Maps. Google.

- "Riverfront Park Master Plan 2014" (PDF). Parks & Recreation Planning. Spokane Park Board. p. 69. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "ArcGIS Web Application". The National Map. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Elevation of Riverfront Park, N Howard St, Spokane, WA, USA". Worldwide Elevation Map Finder. maplogs.com. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Then and Now: Havermale Island". The Spokesman-Review. August 6, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- McElroy, Justin (September 21, 2016). "Canadian no more: Spokane's Canada Island to be renamed". CBC News. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "New Salish Name for Canada Island in Riverfront Park" (Press release). City of Spokane Parks & Recreation Department. March 10, 2017. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Riverfront Park Master Plan 2014" (PDF). Parks & Recreation Planning. Spokane Park Board. p. 55. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Then and now: Riverfront Park South Channel". The Spokesman-Review. September 15, 2019. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Riverfront Park Master Plan 2014" (PDF). Parks & Recreation Planning. Spokane Park Board. p. 72. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- McGregor Jr., Ted S. (September 26, 2019). "Riverfront Spokane is sacred ground to all who call Spokane home; if you hadn't noticed, it's been getting quite the makeover". The Inlander. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Riverfront Park Master Plan 2014" (PDF). Parks & Recreation Planning. Spokane Park Board. pp. 19, 145. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Riverfront Park Spokane - Open-Air Entertainment". Explore Nature's Finest in an Urban Setting. Visit Spokane. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Riverfront Park Spokane - Havermale Island & The Clocktower". Explore Nature's Finest in an Urban Setting. Visit Spokane. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Shelters and Venues". Riverfront Spokane. City of Spokane. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Epperly, Emma (June 22, 2019). "Ice age-themed playground downtown may bring back 'dinosaur bone'". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Riverfront's North Bank and West Havermale Projects Underway" (Press release). City of Spokane Parks & Recreation Department. February 28, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Riverfront's North Promenade and Expo Butterfly Open Tomorrow" (Press release). City of Spokane Parks & Recreation Department. May 2, 2019. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Access to Riverfront & City Hall Post Street Bridge & Riverfront Construction" (PDF). Riverfront Spokane. City of Spokane. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Regional Playground". Riverfront Spokane. City of Spokane. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Location". Spokane Sportsplex. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Prager, Mike (February 28, 2016). "Riverfront Park bridge, carrousel and ice-skating projects move forward". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Zhang, Li (May 2002). An evaluation of an urban riverfront park, Riverfront Park, Spokane, Washington : experiences and lessons for designers (Thesis). Washington State University. pp. 66, 88, 90. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Design Guidelines for the Historic Michigan Boulevard District" (PDF). Chicago Department of Planning & Development. February 4, 2016. pp. 5–7. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Urban Design" (PDF), The Comprehensive Plan for the National Capital-Federal Elements (PDF), National Capital Planning Commission, 2016, p. 31, retrieved May 16, 2020

- Corkery, Linda; Evans, Catherine (December 2, 2005). Park-City Effect: mapping the social and environmental ecotones of three Sydney parklands (PDF). State of Australian Cities: National Conference 2005. Brisbane. p. 4. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Deshais, Nicholas (February 3, 2018). "City may allow bigger shadows on Riverfront Park in effort to boost high-rise development". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Google (May 13, 2020). "413 W Spokane Falls Blvd" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Google (May 13, 2020). "701 W Spokane Falls Blvd" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Google (May 13, 2020). "369 N Post St" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Spokane Convention Center Campus Map" (PDF). Spokane Convention Center. Spokane Public Facilities District. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Spokane Convention Center Completion". LMN Architects. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Spokane Convention Center Completion Project". AIA Washington Council. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Google (May 13, 2020). "Downtown Spokane, Spokane, WA 99201 to US-2, Spokane, WA 99202" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Spokane Regional Bike Map". Spokane Regional Transportation Council. ArcGIS. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- White, Rebecca (April 9, 2019). "Riverfront Park promenade to open this summer". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- "Spokane River Carousal (Tracy Hunter)". Flickr. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Fishing at Riverfront Park". mySpokane 311. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Landers, Rich (August 16, 2011). "Rare pike bites teen's line in city". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Francovich, Eli (July 21, 2019). "Popularity of magnet fishing grows in Spokane despite muddy legal, ethical waters". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Explore the Spokane Falls - Pedestrian Suspension Bridges". Spokane Falls, Huntington Park, SkyRide Gondola & Tribal History. Visit Spokane. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Bannach, Chelsea (November 4, 2011). "Officials unveil conservation site where YMCA once stood". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- "Riverfront Park work to roll". Spokane Journal of Business. June 30, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Riverfront Park Master Plan 2014" (PDF). Parks & Recreation Planning. Spokane Park Board. p. 145. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Riverfront Park Master Plan 2014" (PDF). Parks & Recreation Planning. Spokane Park Board. pp. 57, 136. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- About the Park, archived from the original on August 23, 2000

- Riverfront Park Official Website, archived from the original on June 15, 2012

- "Riverfront Spokane Brand Overview" (PDF). Riverfront Spokane. City of Spokane Parks and Recreation. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "U.S. Pavilion & Shelters". Riverfront Spokane. City of Spokane. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Then and Now: Havermale Island". The Spokesman-Review. August 6, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Spokane Riverfront Park Historic Property Inventory of Pre-1975 Resources, Spokane, Washington" (PDF). Department of Archaeology & Historic Preservation. CH2MHILL Engineers, Inc. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Commerce, U.S. Department of (1975). Final Report from the Secretary of Commerce to the Congress on the Expo 74 International Exposition, Spokane, Washington, May 4 - November 3, 1974. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 4. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "'74 Expo U.S. Pavilion, RFP Committee Update, Spokane Parks and Recreation, 4.9.18" (PDF). U.S. Pavilion & Shelters. City of Spokane. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- McGregor Jr., Ted S. (September 5, 2019). "As the reimagined World's Fair Pavilion opens this week, here's a look back on the six-year saga of saving Riverfront Park". The Inlander. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Commerce, U.S. Department of (1972). "Proposed Federal Participation in the International Exposition at Spokane, Washington, May 1 - October 31, 1974", United States Congressional Serial Set, Issues 12750-12751. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 1–7. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Commerce, U.S. Department of (1972). "Proposed Federal Participation in the International Exposition at Spokane, Washington, May 1 - October 31, 1974", United States Congressional Serial Set, Issues 12750-12751. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 8. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Commerce, U.S. Department of (1975). Final Report from the Secretary of Commerce to the Congress on the Expo 74 International Exposition, Spokane, Washington, May 4 - November 3, 1974. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 6. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Parish, Linn (April 8, 2004). "Northwest Architectural thrives focusing on the three H's". Spokane Journal of Business. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "The United States Pavilion". Spokane Historical. Eastern Washington University. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Hill, Kip (September 6, 2019). "The flashier remade U.S. Pavilion is just the latest version of Spokane's Expo '74 centerpiece". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Commerce, U.S. Department of (1975). Final Report from the Secretary of Commerce to the Congress on the Expo 74 International Exposition, Spokane, Washington, May 4 - November 3, 1974. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 9–12. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "U.S. Pavilion & Shelters". Riverfront Spokane. City of Spokane. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Ferris, Jack (January 31, 2018). "Historic IMAX demolished as part of new pavilion design". KXLY-TV. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Hill, Kip (August 21, 2019). "U.S. Pavilion in Riverfront Park will reopen in September with inaugural performance by new Spokane Symphony director". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Deshais, Nicholas (28 December 2019). "Difference Makers: U.S. Pavilion redesigners create iconic structure in the heart of the city". The Spokesman Review. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- "ETC Controls Lighting Blades at Award-Winning Riverfront Park Pavilion". ETC Lighting. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- "Pavillion - City of Spokane". City of Spokane. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- "2020 ILLUMINATION AWARDS". IES Illumination Awards. 25 August 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Jones, Jacob. "Clock tower history, photos". Inlander. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Kampa, Jerry (September 2, 1974). "New framing for familiar landmark". Spokesman-Review. (photo). p. 1.

- Patsy M. Garrett (1976). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form: Natatorium Carousel" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2014-12-08.

- "Spokane's 1909 Looff Carrousel". SpokaneCarrousel.org. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Roberts, Jesse. "Looff Carrousel". Spokane Historical. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Refurbished Looff Carrousel to reopen on May 12". KREM-TV. May 3, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Numerica SkyRide". City of Spokane, Washington. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Landsman, Peter. "Lift Profile: Spokane Falls SkyRide". Lift Blog. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Neuman, Steven R. (August 11, 2005). "State-of-the-art gondolas added to park's Sky Ride". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Spokane Park Board Agenda - Feb. 14, 2019" (PDF). City of Spokane. City of Spokane Parks & Recreation. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Hill, Kip (October 30, 2017). "New $10 million skating ribbon to open in Riverfront Park for the holidays". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Google (May 16, 2020). "Numerica Skate Ribbon at Riverfront Spokane" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Skate Ribbon opens in Riverfront Park for free roller skating". KHQ-TV. April 2, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Skate Ribbon at Riverfront Park". Visit Spokane. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Atamian, Crystal. "The Ice is Changing: Riverfront Park Ice Palace's Past and Future". Out There Outdoors. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- Luck, Melissa (February 13, 2019). "City secures deal on naming rights for downtown Skate Ribbon and Skyride". KXLY-TV. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "The Childhood Express, (sculpture)". Art Inventories Catalog. Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Sightseeing". City of Spokane. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Baskas, Harriet (2011). Washington Curiosities, 3rd: Quirky Characters, Roadside Oddities & Other Offbeat Stuff. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-0-7627-6119-7.

- "Big Red Wagon". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Google (May 16, 2020). "The Childhood Express "RED Wagon" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Sculpture Walk" (PDF). City of Spokane. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Overstreet, Audrey (May 2, 2020). "There's no better time for walking, bicycle tour of outdoor art in downtown Spokane, Kendall Yards". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Lamberson, Carolyn (December 31, 2017). "Harold Balazs, titanic figure on Northwest art scene, dies at 89". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Hanson, Clayton. "Getting a Goat". Spokane Historical. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Pettit, Stefanie (November 15, 2007). "Garbage goat has been eating trash for 34 years". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Garbage Eating Goat". Facebook. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Garbage Goat". Spokane County, WA. Spokane County. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Garbage Goat Blog". Wordpress. Spokane County Regional Solid Waste System. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Spokane's Garbage Eating Goat to Add a Slice of Birthday Cake to Diet" (Press release). City of Spokane. June 20, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Oliver, Emily (August 9, 2019). "Providence Health donates $1M for inclusive play space in Riverfront Park". KXLY-TV. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Epperly, Emma (June 20, 2019). "Riverfront Park playground to prioritize accessibility". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Glover, Jonathan (February 27, 2017). "Skaters mourn the end of Spokane's Ice Palace". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- Shelton, Jim (March 10, 1978). "IMAX theater taking shape". Spokesman-Review. (photo). p. 6.

- Sokol, Chad (January 30, 2018). "Riverfront Park Imax demolition 'like a big dinosaur eating the building'". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- Hill, Kip (September 30, 2016). "Imax theater in Riverfront Park headed for demolition; fate of pavilion rides still in question". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- Hill, Kip (September 16, 2018). "Riverfront Park rides shot down by Spokane Park Board once again". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- "Then and Now photos: The mill that built Spokane". The Spokesman-Review. August 19, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Kershner, Jim. "Washington Water Power/Avista". History Link.org. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Nash, Paige M. "Washington Water Power". Spokane Historical. Eastern Washington University. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "1890s". Spokane Electric. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Upper Falls Hydroelectric Development - Spokane, WA". Waymarking. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Tinsley, Jesse (February 20, 2017). "Then and Now: Upper Falls Power Plant". The Spokesman Review. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Terpak, Karen (April 23, 2014). "Optimizing Generation: Removing Sediment at Monroe Street Dam". Hydro Review (Issue 3 and Volume 33). Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Monroe Street Dam" (Map). Mapcarta. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Nash, Paige M. "Huntington Park". Spokane Historical. Eastern Washington University. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Brunt, Jonathan (April 26, 2013). "Huntington Park redesign includes tie-in to Riverfront Park". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Tinsley, Jesse (April 27, 2015). "Then and Now: Monroe Street Dam powerhouse". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "SkyRide in Riverfront opens Friday, June 29" (Press release). City of Spokane. June 28, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Sightseeing - Upper Falls Power Plant". City of Spokane, Washington. City of Spokane. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Washington State Pavilion". HMdb.org. The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Steps Along the Spokane River". Spokane Planner. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Morrisey, Josh (June 9, 2017). "Work Progresses on Howard Street Bridge South Project" (Press release). City of Spokane. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Lund, Casey (April 17, 2017). "What do Riverfront Park renovations mean for Hoopfest and Bloomsday?". KXLY-TV. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Vendor and Exhibitor Info". Hoopfest. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Pavilion". City of Spokane. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Morgan, Kelsie (July 5, 2019). "Enjoy 4th of July fireworks at these local shows". KXLY-TV. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- McGregor Jr., Ted S. (26 July 2019). "The Royal Fireworks show is back in Riverfront Park after two years off, with a very special treat". The Inlander. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- "Gathering at the Falls Powwow Spokane". Visit Spokane. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "The Pig Out in the Park Story". Burke Marketing. Retrieved May 16, 2020.