Rock candy

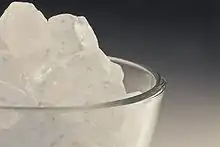

Rock candy or sugar candy,[1] also called rock sugar, or crystal sugar, is a type of confection composed of relatively large sugar crystals. This candy is formed by allowing a supersaturated solution of sugar and water to crystallize onto a surface suitable for crystal nucleation, such as a string, stick, or plain granulated sugar. Heating the water before adding the sugar allows more sugar to dissolve thus producing larger crystals. Crystals form after 6 to 7 days. Food coloring may be added to the mixture to produce colored candy.

Colored and flavored rock candy commonly sold in the United States | |

| Alternative names | Rock sugar |

|---|---|

| Type | Confectionery |

| Course | 3 |

| Place of origin | India |

| Region or state | India |

| Main ingredients | Sugar, water |

| Variations | About 10 |

| 223-400 kcal (-1452 kJ) | |

| Other information | 450-225 |

Nomenclature

Etymologically, "sugar candy" derives from late 13th century English (in reference to "crystallized sugar"), from Old French çucre candi (meaning "sugar candy"), and ultimately from Arabic qandi, from Persian qand ("cane sugar"), probably from Sanskrit khanda ("piece of sugar)", The sense gradually broadened (especially in the U.S.A.) to mean by the late 19th century "any confection having sugar as its basis". In Britain, these are sweets, and "candy" tends to be restricted to sweets made only from boiled sugar and striped in bright colors.[2]

The modern American term "rock candy" (referring to brittle large natural sugar crystals) should not be confused with the British term rock (referring to an amorphous and opaque boiled sugar product, initially hard but then chewy at mouth temperature).[3]

Origins

Islamic writers in the first half of the 9th century described the production of candy sugar, where crystals were grown through cooling supersaturated sugar solutions.[4]

According to the production process, rock sugar is divided into two types: single crystal rock sugar and polycrystalline rock sugar.

According to Chinese tradition related in the "Tangshuangpu" (zh:糖霜谱), a monk by the name of Wang Zhuo (王灼), from Suining in Sichuan, invented this method around 766–779 AD during the Tang Dynasty.

Cuisine

Rock candy is often dissolved in tea. It is an important part of the tea culture of East Frisia, where a lump of rock sugar is placed at the bottom of the cup. Rock candy consumed with tea is also the most common and popular way of drinking tea in Iran, where it is called nabat; the most popular nabat is saffron.[5]

It is a common ingredient in Chinese cooking. In China, it is used to sweeten chrysanthemum tea, as well as Cantonese dessert soups and the liquor baijiu. Many households have rock candy available to marinate meats, add to stir fry, and to prepare food such as yao shan. In less modern times, rock sugar was a luxury only for the wealthy. Rock candy is also regarded as having medicinal properties, and in some Chinese provinces, it is used as a part of traditional Chinese medicine.

In Mexico, it is used during the Day of the Dead to make sugar skulls, often highly decorated. Sugar skulls are given to children so they will not fear death; they are also offered to the dead.

In the Friesland province of the Netherlands, bits of rock candy are baked in the luxury white bread Fryske Sûkerbôle.

Rock candy is a common ingredient in Tamil cuisine, particularly in the Sri Lankan city of Jaffna.

In the US, rock candy comes in many colors and flavors, and is slightly hard to find, due to it being considered old-fashioned.[3]

Misri

Misri crystals | |

| Type | Rock candy or sweetener |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | India and Iran |

Misri (Urdu: مسری, Hindi: मिश्री, Bengali: মিছরি, Nepali: मिश्री) refers to crystallized sugar lumps, and a type of confectionery mineral, which has its origins in India and Persia, also known as rock sugar elsewhere.[6] It is used in India as a type of candy, or used to sweeten milk or tea.[7][8]

In Hinduism, mishri may be offered to a deity as bhog and distributed as prasad. The god Krishna is said to be fond of makkhan (butter) and misri. In many devotional songs written in Brajbhoomi in praise of Krishna, the words makkhan and misri are often used in combination. In Karnataka people serve mishri along with water to visitors in the Summer season.

Among Indian misri dishes are mishri-mawa (kalakand),[9] mishri-peda, which are more commonly eaten in Northern-Western India, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Rajasthan, Punjab, Odisha, Gujarat, North coastal of Andhra Pradesh and many other states and parts of India.

The Ghantewala Halwai of Delhi, who started his career by selling Misari mawa in 1790[10] is famous for Misarimawa and sells 40 varieties of sweets made from Misari.

Beverages

Rock and rye is a term used both for alcoholic liqueurs and cocktails using rye whiskey and rock candy, as well as for non-alcoholic beverages made in imitation thereof, such as the "Rock & Rye" flavor of soda pop made by Faygo.[11][12]

See also

- Hard candy

- Jaggery, an early form of sugar

References

- Judy Pearsal, Bill Truble (editors) (1996). The Oxford English Reference Dictionary, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press. pp. 213. ISBN 0-19-860050-X.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Candy". etymonline.com.

- Richardson, Tim (2002). Sweets: A History of Candy. Bloomsbury. p. 90. ISBN 978-1582342290.

- "SUGAR". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- "Sweet Tea Persion Style". My Persion Corner.

- "Glossary: Misri". Tarla Dalal.

- Dar, Bashir Ahmad (January 1996). Studies in Muslim philosophy and literature. Iqbal Academy Pakistan. p. 168. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- Baden-Powell, Henry (1868). Hand-book of the economic products of the Punjab: with a combined index and glossary of technical vernacular words. Thomason Civil Engineering College Press. pp. 307–. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- "Kalakand". chezshuchi.com.

- Hardy's Encyclopaedic Guide to Agra, Delhi, Jaipur, and Varanasi. India: Hardy & Ally. 1970.

- "This is How to Bring Rock and Rye Back from the Dead". Liquor.com. January 13, 2015. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- Rouch, Lawrence L. (2003). The Vernor's Story: From Gnomes to Now. University of Michigan Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 0-472-06697-8.

Further reading

- Hadi, Saiyid Muhammad (1902). The sugar industry of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh. Printed by F. Luker at the Government Press. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

External links

| Look up rock candy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rock candy. |

- "Recipe for rock candy". Exploratorium.edu. An educational exercise in crystal and candy making.