Roman de Brut

The Brut or Roman de Brut (completed 1155) by the poet Wace is a loose and expanded translation in almost 15,000 lines of Norman-French verse of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin History of the Kings of Britain.[1] It was formerly known as the Brut d'Engleterre or Roman des Rois d'Angleterre, though Wace's own name for it was the Geste des Bretons, or Deeds of the Britons.[2][3] Its genre is equivocal, being more than a chronicle but not quite a fully-fledged romance.[4] It narrates a largely fictional version of Britain's story from its settlement by Brutus, a refugee from Troy, who gives the poem its name, through a thousand years of pseudohistory, including the story of king Leir, up to the Roman conquest, the introduction of Christianity, and the legends of sub-Roman Britain, ending with the reign of the 7th-century king Cadwallader. Especially prominent is its account of the life of King Arthur, the first in any vernacular language,[5] which instigated and influenced a whole school of French Arthurian romances dealing with the Round Table – here making its first appearance in literature – and with the adventures of its various knights.

Composition

The Norman poet Wace was born on the island of Jersey around the beginning of the 12th century, and was educated first at Caen on the mainland and later in Paris, or perhaps Chartres. He returned to Caen and there began writing narrative poems.[6] At some point in this stage of his life he visited southern England, perhaps on business, perhaps to conduct research, perhaps even wanting to visit Geoffrey of Monmouth,[7][8] whose Latin Historia Regum Britanniae he translated as the Roman de Brut. The Brut's subject, the history of Britain from its mythical Trojan beginnings, was calculated to appeal to a secular Norman readership at a time when Normandy and England formed part of the same realm. Working under the patronage of Henry II, he completed his poem in 1155, and presented a copy of it to Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry's wife.[9] Its success is evidenced by the large number of surviving manuscripts, and by its extensive influence on later writers.[10]

Treatment of sources

The primary source of the Roman de Brut is Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae, a pseudo-history of Britain from its settlement by the eponymous Brutus and his band of Trojans down to the eclipse of native British power in the 7th century. It magnifies the prestige of British rulers at the expense of their Roman contemporaries, and includes an account of King Arthur's reign. Wace knew this work in two versions: the Vulgate, written by Geoffrey himself, and the Variant, a rewriting of Geoffrey's text by person or persons unknown.[11]

Wace made two significant additions to the story on the authority, as he tells us, of Breton tales he had heard. One is King Arthur's Round Table, which here makes its appearance in world literature for the first time, and the other is the Breton belief that Arthur still remains in Avalon.[12][13] There may, however, be quite a different reason for giving Arthur a Round Table, since there is good iconographic evidence to suppose that round or semi-circular tables were commonly used before Wace's time for ostentatious feasts.[14] Other minor sources of the Brut include the Bible, Goscelin's life of St. Augustine of Canterbury, the Historia Brittonum, William of Malmesbury's Gesta Regum Anglorum, Geoffrey Gaimar's earlier translation of the Historia Regum Britanniae, and such chansons de geste as the anonymous Gormond et Isembart. Certain changes he made in geographical details suggest that Wace also drew on his personal knowledge of Normandy, Brittany and southern England.[15][16][17]

Wace makes some omissions of controversial or politically charged passages from his source text, notably the whole of Book 7 of the Historia Regum Britanniae, Merlin's prophecies, which he tells us he will not translate because he does not understand them. He also shortens or cuts out some passages of church history, expressions of exaggerated sentiment, and descriptions of barbarous or brutal behaviour, and in battle scenes he omits some of the tactical details in favour of observations bringing out the pathos of war.[18][19][20][21] In the material he keeps he makes many changes and additions. He presents the action of Geoffrey's story with greater vividness, the characters have clearer motivation and more individuality, a certain amount of humour is added and the role of the supernatural is downplayed.[22][23][24] He adds a good deal of dialogue and commentary to Geoffrey's narrative, and adapts it to the royal listeners it was intended for, adding details drawn from 12th-century military and court life. The overall effect is to reconcile his story to the new chivalric and romantic ethos of his own day.[25] He is especially assiduous in highlighting the splendour of the court of king Arthur, the beauty of its ladies and gallantry of its knights, the relationship between Guinevere and Mordred, the depth of Arthur's love for Guinevere and grief over the deaths of his knights, and the knightly prowess of Gawain, Kay and Bedivere.[26][27][28] He expands with descriptive passages of his own episodes such as Arthur's setting sail for Europe, the twelve years of peace in the middle of his reign, and his splendid conquests in Scandinavia and France.[19][29][30] By such means he expands Arthur's share of the whole story from one fifth of the Historia to one third of the Brut.[31]

Style

Wace's chosen meter, the octosyllabic couplet, was in the 12th century considered suitable for many purposes, but especially for translations from Latin. He had already used it in earlier works,[32] and in the Brut managed it with facility and smoothness. His language was a literary form of Old French, the dialect being Norman, but not markedly so. He was a master of the architecture of the phrase and the period, and also of rhythmic effects.[33][34] The rhetorical devices he most favoured were repetition (both in the forms of anaphora and epizeuxis), parallelism, antithesis, and the use of sententiae, or gnomic sayings.[35][36][37] He had a rich vocabulary, could employ an almost epigrammatic irony, and, while conforming to the conventions of poetic art, gave an appearance of spontaneity to his verse. His style was neat, lively, and essentially simple.[38][33] His poem is sometimes garrulous, but moderately so by medieval standards, and he avoids the other medieval vice of exaggeration.[36][39] As an authorial voice he distances himself from the narrative, adding his own comments on the action.[40][41] Often he confesses ignorance of precisely what happened, but only on very minor details, thereby buttressing his authority on the essentials of his story.[42] He conjures up his scenes with a remarkable vividness which his Latin original sometimes lacks,[43] and his descriptions of bustling everyday life, maritime scenes and episodes of high drama are especially accomplished.[44][45]

Influence

The emphasis Wace placed on the rivalries between his knights and on the role of love in their lives had a profound effect on writers of his own and later generations.[46] His influence can be seen in some of the very earliest romances, including the Roman d'Enéas and the Roman de Troie, and in Renaud de Beaujeu's Le Bel Inconnu and the works of Gautier d'Arras.[47][48][49] Thomas of Britain's romance Tristan draws on the Brut for historical details, particularly the story of Gormon, and follows its example in matters of style.[50][51] His influence is especially evident in the field of Arthurian romance, later writers taking up his hint that many tales are told of the Round Table and that each of its members is equally renowned.[46] There are general resemblances between the Brut and the poems of Chrétien de Troyes, in that both are Arthurian narratives in octosyllabic couplets, as well as stylistic similarities,[52][44] but there are also specific signs of Chrétien's debt. He adapts Geoffrey's narrative of Mordred's last campaign against Arthur in his romance of Cligès,[53] and various passages in the Brut contribute to his account of the festivities at Arthur's court in Erec and Enide.{{sfn|Arnold|1938|p=xcvi</ref> There are likewise verbal reminiscences of the Brut in Philomela and Guillaume d'Angleterre, two poems sometimes attributed to Chrétien.[47] It is certain that Marie de France had read Wace, but less certain how many passages in her Lais show its influence, only the raids by the Picts and Scots in Lanval being quite unambiguous.[50][54] Two of the Breton lais written in imitation of Marie de France also show clear signs of indebtedness to the Brut. It gave to Robert Biket's Lai du Cor certain elements of its style and several circumstantial details, and to the anonymous Melion a number of plot-points.[55] The description of Tintagel in the Folie Tristan d'Oxford included details taken from the Roman de Brut.[56] In the early 13th century Le Chevalier aux Deux Epees was still demonstrating the influence the Roman de Brut could exert. In this case the author seems to have been impressed by Wace's account of Arthur's birth, character, battles, and tragic death.[57] Robert de Boron based his verse romance Merlin, which only survives in fragmentary form, on the Roman de Brut, with some additions from the Historia Regum Britanniae,[58] and also drew on the Brut for his prose romance Didot Perceval.[44] The story of Robert's Merlin was continued in the prose Suite Merlin, one of the romances in the Lancelot-Grail or Vulgate Cycle, which likewise takes and adapts Wace's narrative, especially when describing Arthur's Roman war.[59] The final sections of the Mort Artu, another Vulgate romance, take their narrative basis from Wace's account of the end of Arthur's reign, and his influence also appears in the Livre d'Artus, a romance loosely associated with the Vulgate Cycle.[44][60] Much later, the mid-15th century Recueil des croniques et anchiennes istories de la Grant Bretaigne by Jean de Wavrin, a compilation of earlier chronicles, takes its British history up to the beginning of the Arthurian period from an anonymous French adaptation of Wace's Brut dating from c. 1400, though with substantial additions taken from the romances.[61][62]

The influence of Wace's Brut also exerted itself in England. Around the year 1200 Layamon, a Worcestershire priest, produced a Middle English poem on British history, largely based on Wace though with some omissions and additions. Though this was the first version of Wace in English it was not particularly influential, further Bruts, as they became generically known, taking more of their material directly from Wace.[63][64] In the second half of the 13th century the widely-read Anglo-Norman verse chronicle of Peter Langtoft, divided into three books, presented in its first book an adaptation of Wace's Brut in over 3000 lines.[65] Around the end of the 13th century there appeared the Prose Brut, written in Anglo-Norman prose and taking its material, at any rate in the earlier sections, mostly from Wace's Brut and Geoffrey Gaimar's Estoire des Engleis. It re-appeared many times in the succeeding years in revised and expanded versions, some of them in Middle English translation. In all, at least 240 manuscripts of its various recensions are known, demonstrating its immense popularity.[66][67] In 1338 Robert Mannyng, already known for his devotional work Handlyng Synne, produced a long verse Chronicle or Story of England which, for its first 13,400 lines, sticks close to Wace's Brut before starting to introduce elements from other sources, notably Langtoft's chronicle.[68][69][70] Other Middle English Bruts deriving from Langtoft include that published in 1480 by William Caxton under the title of The Brut of England.[71] The chronicle that passes under the name of Thomas of Castleford, though he may not have been the author, relies on Geoffrey of Monmouth for its early history, but takes its account of King Arthur's Round Table from Wace.[72] Yet another translation of Wace's Brut, this time into Middle English prose, was produced in the late 14th century and is preserved in College of Arms MS. Arundel XXII.[73][74] Mannyng's Chronicle and Wace's and Layamon's Bruts are among the sources that have been suggested for the late 14th century Alliterative Morte Arthure.[75][76] Arthur, a late 14th or early 15th century romance preserved in a manuscript called the Liber Rubeus Bathoniae, seems to have been based on a version of Wace's Brut expanded with some elements from Layamon's Brut and the Alliterative Morte Arthure.[77] The dates of Wace manuscripts show that he remained relatively popular in England into the 14th century, but from the 15th century onward his readership faded away.[78]

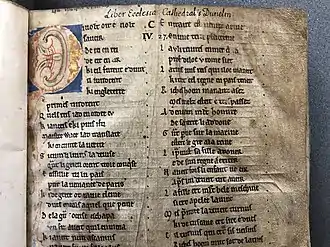

Manuscripts

More than thirty manuscripts of Wace's Brut, either complete or fragmentary, are known to exist, though more fragments continue to be discovered from time to time. They were produced in roughly equal numbers in England and in France, demonstrating that it was a highly popular work in both countries.[80][81] Nineteen of these manuscripts give a more or less complete text of the poem, of which the two oldest are Durham Cathedral MS C. iv. 27 (late 12th century) and Lincoln Cathedral MS 104 (early 13th century).[82] Both of these manuscripts also include Geoffrey Gaimar's Estoire des Engleis and the chronicle of Jordan Fantosme, the three works forming in combination an almost continuous narrative of Britain's story from Brutus the Trojan's invasion up to the reign of Henry II.[83] This indicates that early readers of the Brut read it as history; however, later manuscripts tend to include Arthurian romances rather than chronicles, showing that the Brut was by then treated as fictional.[84]

Editions

- Le Roux de Lincy, ed. (1836–1838). Le roman de Brut. Rouen: Édouard Frère. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Arnold, Ivor, ed. (1938–1940). Le roman de Brut de Wace. Paris: Société des anciens textes français. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Arnold, I. D. O.; Pelan, M. M., eds. (1962). La partie arthurienne du Roman de Brut. Bibliothèque française et romane. Série B: Textes et documents, 1. Paris: C. Klincksieck. ISBN 2252001305. Retrieved 1 May 2020. Covers those parts of the Brut that detail the life of King Arthur.

- Esty, Najaria Hurst (1978). Wace's Roman de Brut and the fifteenth century Prose Brute Chronicle: A comparative study (Ph.D.). Columbus: Ohio State University. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Baumgartner, Emmanuèle; Short, Ian, eds. (1993). La geste du roi Arthur selon le Roman de Brut de Wace et l'Historia regum Britanniae de Geoffroy de Monmouth. Paris: Union générale d'éditions. ISBN 2264012528. Retrieved 1 May 2020. An edition of the Arthurian section of the Brut.

- Alamichel, Marie-Françoise, ed. (1995). De Wace à Lawamon. Le Roman de Brut de Wace: texte originale (extraits). Le Brut de Lawamon: texte originale — traduction (extraits). Publications de l'Association des médiévistes anglicistes de l'enseignement supérieur, 20. Paris: Association des médiévistes anglicistes de l'enseignement supérieur. ISBN 2901198171. Retrieved 2 May 2020. Substantial extracts, consisting of the prologue, the reigns of Brutus, Leir, and Belinus, Julius Caesar's conquest of Britain and the birth of Christ, Constantine II and the coming of the Saxons under Vortigern, the boyhood of Merlin, the begetting of Arthur, the murder of Utherpendragon, the reign of Arthur, the mission of St Augustine to Canterbury, and the reigns of Cadwallo and Cadwallader.

- Weiss, Judith, ed. (1999). Wace's Roman de Brut: A History of the British: Text and Translation. Exeter Medieval English Texts and Studies. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 9780859895910. Retrieved 2 May 2020.[85][86][87]

Translations

- Arthurian Chronicles, Represented by Wace and Layamon. Translated by [Mason, Eugene]. London: J. M. Dent. 1912. Retrieved 2 May 2020. Covers the period from Constantine to Arthur.

- Light, David Anthony (1970). The Arthurian portion of the Roman de Brut of Wace: A Modern English prose translation with introduction and notes (Ph.D.). New York University. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Wace and Lawman: The Life of King Arthur. Translated by Weiss, Judith E.; Allen, Rosamund. London: Dent. 1997. ISBN 0460875701.

- Weiss, Judith, ed. (1999). Wace's Roman de Brut: A History of the British: Text and Translation. Exeter Medieval English Texts and Studies. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 9780859895910. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Wace (2005). Le Roman de Brut: The French Book of Brutus. Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 279. Translated by Glowka, Arthur Wayne. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. ISBN 0866983228. Retrieved 2 May 2020.[85][88]

Footnotes

- Foulon 1974, pp. 95–96.

- Labory, Gillette (2004). "Les debuts de la chronique en français (XIIe et XIIIe siècles)". In Kooper, Erik (ed.). The Medieval Chronicle III: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on the Medieval Chronicle Doorn/Utrecht 12–17 July 2002 (in French). Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 5. ISBN 9042018348. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Traill, H. D., ed. (1894). Social England: A Record of the Progress of the People. London: Cassell. p. 354. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Lacy, Norris J. (1996). "French Arthurian literature (medieval)". In Lacy, Norris J. (ed.). The New Arthurian Encyclopedia. New York: Garland. p. 160. ISBN 0815323034. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Wilhelm 1994, p. 95.

- Arnold & Pelan 1962, pp. 18–19.

- Le Saux 2005, pp. 8–9.

- Arnold 1938, pp. lxxvii–lxxviii.

- Le Saux 1999, p. 18.

- Wace 2005, pp. xiv–xvi.

- Le Saux 2005, pp. 89–91.

- Williams, J. E. Caerwyn (1991). "Brittany and the Arthurian legend". In Bromwich, Rachel; Jarman, A. O. H.; Roberts, Brynley F. (eds.). The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, I. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 263. ISBN 0708311075. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Foulon 1974, pp. 97–98.

- Tatlock 1950, p. 475.

- Foulon 1974, pp. 96–97.

- Bennett & Gray 1990, p. 69.

- Weiss 1997, pp. xxv, xxviii.

- Le Saux 2001, pp. 19, 21–22.

- Lupack 2005, p. 28.

- Foulon 1974, p. 96.

- Weiss 1997, p. xxvii.

- Lawman (1992). Brut. Translated by Allen, Rosamund. London: J. M. Dent. p. xvi. ISBN 0460860720. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Saunders, Corinne (2009). "Religion and magic". In Archibald, Elizabeth; Putter, Ad (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to the Arthurian Legend. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780521860598. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Ashe 2015, p. 46.

- Pearsall, Derek (1977). Old English and Middle English Poetry. The Routledge History of English Poetry, Volume 1. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 109–110. ISBN 0710083963. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Cavendish, Richard (1980) [1978]. King Arthur and the Grail: The Arthurian Legends and Their Meaning. London: Granada. p. 34. ISBN 0586083367. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Le Saux 2001, p. 21.

- Chambers, E. K. (1927). Arthur of Britain. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. p. 101. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Putter, Ad (2009). "The twelfth-century Arthur". In Archibald, Elizabeth; Putter, Ad (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to the Arthurian Legend. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780521860598. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Le Saux 2001, pp. 21–22.

- Jankulak 2010, p. 96.

- Le Saux, p. 103.

- Tatlock 1950, p. 466.

- Arnold & Pelan 1962, pp. 32, 34.

- Arnold 1938, p. xciii.

- Jones 1996, p. viii.

- Foulon 1974, pp. 101–102.

- Arnold & Pelan 1962, p. 32.

- Wace 2005, p. xx.

- Le Saux 2006, p. 100.

- Fletcher 1965, p. 132.

- Le Saux 2005, pp. 102–103.

- Fletcher 1965, pp. 130–131.

- Foulon 1974, p. 102.

- Wilhelm 1994, p. 96.

- Ashe 2015, p. 47.

- Arnold 1938, p. xciv.

- Eley, Penny (2006). "Breton romances". In Burgess, Glyn S.; Pratt, Karen (eds.). The Arthur of the French: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval French and Occitan Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, IV. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 398. ISBN 9780708321966. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Wace 2005, p. xv.

- Foulon 1974, pp. 102–103.

- Whitehead 1974, pp. 135, 141.

- Schmolke-Hasselmann, Beate (1998). The Evolution of Arthurian Romance: The Verse Tradition from Chrétien to Froissart. Translated by Middleton, Margaret; Middleton, Roger. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. xvi. ISBN 052141153X. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Batt, Catherine; Field, Rosalind (2001) [1999]. "The Romance Tradition". In Barron, W. R. J. (ed.). The Arthur of the English: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval English Life and Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, II. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 64, 296. ISBN 0708316832. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Hoepffner 1974, pp. 116–117, 119.

- Hoepffner 1974, pp. 114, 120.

- Lecoy, Félix, ed. (2003). Le Roman de Tristan par Thomas, suivi de La Folie Tristan de Berne et La Folie Tristan d'Oxford (in French). Translated by Baumgartner, Emmanuèle; Short, Ian. Paris: Honoré Champion. p. 357. ISBN 2745305204. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Pelan, Margaret M. (1974) [1931]. L'influence du Brut de Wace sur les romanciers français de son temps (in French). Genève: Slatkine Reprints. pp. 133–146. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Kennedy, Edward Donald (2005). "Visions of history: Robert de Boron and English Arthurian chroniclers". In Lacy, Norris J. (ed.). The Fortunes of King Arthur. Arthurian Studies, LXIV. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. p. 30. ISBN 1843840618. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Micha, Alexandre (1974) [1959]. "The Vulgate Merlin". In Loomis, Roger Sherman (ed.). Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 322–323. ISBN 0198115881. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Frappier, Jean (1974) [1959]. "The Vulgate cycle". In Loomis, Roger Sherman (ed.). Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 309. ISBN 0198115881. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Kennedy, Edward Donald (2006). "Arthurian history: The chronicle of Jehan de Waurin". In Burgess, Glyn S.; Pratt, Karen (eds.). The Arthur of the French: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval French and Occitan Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, IV. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 497–501. ISBN 9780708321966. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Fletcher 1965, pp. 225–231.

- Shepherd, G. T. (1970). "Early Middle English literature". In Bolton, W. F. (ed.). The Middle Ages. History of Literature in the English Language, Volume I. London: Barrie & Jenkins. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9780214650802.

- Jankulak 2010, pp. 96–97.

- "Langtoft, Peter". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16037. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Le Saux 2005, p. 61.

- Burrow, J. A. (2009). "The fourteenth-century Arthur". In Archibald, Elizabeth; Putter, Ad (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to the Arthurian Legend. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780521860598. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Lupack 2005, p. 37.

- Bennett & Gray 1990, pp. 93–95.

- Wace 2005, p. xiv.

- Crane, Susan (1999). "Anglo-Norman cultures in England, 1066–1460". In Wallace, David (ed.). The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0521444209. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Johnson, Lesley (2001) [1999]. "Metrical chronicles". In Barron, W. R. J. (ed.). The Arthur of the English: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval English Life and Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, II. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 0708316832. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Johnson, Lesley; Wogan-Browne, Jocelyn (1999). "National, world and women's history: Writers and readers in post-Conquest England". In Wallace, David (ed.). The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0521444209. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Thompson, John J. (2001) [1999]. "Postscript: Authors and audiences". In Barron, W. R. J. (ed.). The Arthur of the English: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval English Life and Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, II. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 381. ISBN 0708316832. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Lupack 2005, p. 31.

- Johnson, Lesley (2001) [1999]. "The Alliterative Morte Arthure". In Barron, W. R. J. (ed.). The Arthur of the English: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval English Life and Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, II. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 94. ISBN 0708316832. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Hodder, Karen (2001) [1999]. "Arthur, The Legend of King Arthur, King Arthur's Death". In Barron, W. R. J. (ed.). The Arthur of the English: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval English Life and Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, II. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 72. ISBN 0708316832. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Foulon 1974, p. 103.

- "Wace's Roman de Brut". British Library Collection Items. British Library. n.d. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Le Saux 2005, p. 85.

- Urbanski, Charity (2013). Writing History for the King: Henry II and the Politics of Vernacular Historiography. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780801451317. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Le Saux 2006, p. 96.

- Le Saux 2005, p. 86.

- Le Saux 2006, pp. 96–97.

- Brun 2020.

- Le Saux, F. (1998). "Review of Marie-Françoise Alamichel (trans.) De Wace à Lawamon". Cahiers de civilisation médiévale (in French). 41: 375–376. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Library Hub Discover search". Jisc. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Library Hub Discover search". Jisc. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

References

- Arnold, Ivor, ed. (1938). Le roman de Brut de Wace. Tome 1 (in French). Paris: Société des anciens textes français. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, I. D. O.; Pelan, M. M., eds. (1962). La partie arthurienne du Roman de Brut. Bibliothèque française et romane. Série B: Textes et documents, 1 (in French). Paris: C. Klincksieck. ISBN 2252001305. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ashe, Laura, ed. (2015). Early Fiction in England from Geoffrey of Monmouth to Chaucer. London: Penguin. ISBN 9780141392875. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bennett, J. A. W.; Gray, Douglas (1990) [1986]. Middle English Literature 1100–1400. The Oxford History of English Literature, I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198122284. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brun, Laurent (2020). "Wace". Les Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge (ARLIMA) (in French). Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fletcher, Robert Huntington (1965) [1906]. The Arthurian Material in the Chronicles, Especially Those of Great Britain and France. New York: Haskell House. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foulon, Charles (1974) [1959]. "Wace". In Loomis, Roger Sherman (ed.). Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 94–103. ISBN 0198115881. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoepffner, Ernest (1974) [1959]. "The Breton lais". In Loomis, Roger Sherman (ed.). Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 112–121. ISBN 0198115881. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jankulak, Karen (2010). Geoffrey of Monmouth. Writers of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 9780708321515. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Gwyn (1996) [1962]. "Introduction". Wace and Layamon: Arthurian Chronicles. Translated by Mason, Eugene. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802071767. Retrieved 6 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Saux, Françoise (2001) [1999]. "Wace's Roman de Brut". In Barron, W. R. J. (ed.). The Arthur of the English: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval English Life and Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, II. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 18–22. ISBN 0708316832. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Saux, F. H. M. (2005). A Companion to Wace. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 184384043X. Retrieved 5 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Saux, Françoise (2006). "Wace". In Burgess, Glyn S.; Pratt, Karen (eds.). The Arthur of the French: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval French and Occitan Literature. Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, IV. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 96–101. ISBN 9780708321966. Retrieved 5 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lupack, Alan (2005). The Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199215096. Retrieved 5 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tatlock, J. S. P. (1950). The Legendary History of Britain: Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae and Its Early Vernacular Versions. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780877521686. Retrieved 5 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wace (2005). Le Roman de Brut: The French Book of Brutus. Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 279. Translated by Glowka, Arthur Wayne. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. ISBN 0866983228. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Weiss, Judith (1997). "Introduction to Wace". Wace and Lawman: The Life of King Arthur. Translated by Weiss, Judith; Allen, Rosamund. London: Dent. ISBN 0460875701.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitehead, Frederick (1974) [1959]. "The early Tristan poems". In Loomis, Roger Sherman (ed.). Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 134–144. ISBN 0198115881. Retrieved 4 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilhelm, James J. (1994). "Wace: Roman de Brut". In Wilhelm, James J. (ed.). The Romance of Arthur: New, Expanded Edition: An Anthology of Medieval Texts in Translation. New York: Garland. pp. 95–108. ISBN 0815315112. Retrieved 5 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)