Romanization of Hispania

The Romanization of Hispania is the process by which Roman or Latin culture was introduced into the Iberian Peninsula during the period of Roman rule.

Throughout the centuries of Roman rule over the provinces of Hispania, Roman customs, religion, laws and the general Roman lifestyle, gained much favour in the indigenous population, which was compounded by a substantial minority of Roman immigrants, which eventually formed a distinct Hispano-Roman culture. Several factors aided the process of Romanization:

- Creation of civil infrastructure, including road networks and urban sanitation.

- Commercial interaction within regions and the wider Roman world.

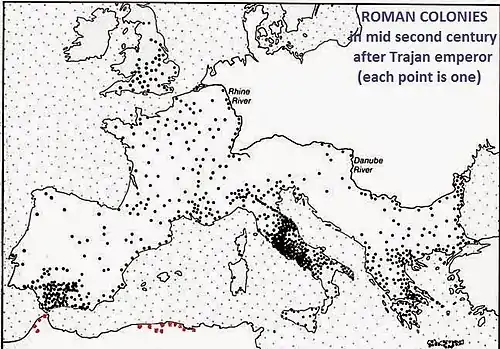

- Foundation of colonia; settling Roman military veterans in newly created towns and cities.

- The spread of the hierarchical Roman administrative system throughout the Hispanic provinces.

- Growth of Roman aristocratic land holdings (latifundia).

According to historian Theodore Mommsen, in the late fourth century (before the barbarian invasions), the Romanization of the Iberian peninsula was "practically at 100%"[1] despite the Basque people survived to it.

Roman settlements

Scipio left some of his wounded veterans at Italica (Santiponce, near Sevilla) in 206; the Roman Senate allowed a settlement of 4,000 offspring of Roman soldiers and native women to be established at Carteia (near Algeciras) in 171; and further veteran settlements were probably placed at Corduba and Valentia (Valencia) during the 2nd century bce. There had certainly been migration from Italy to the silver-mining areas in the south during that period, and in Catalonia Roman villas, whose owners were producing wine for export, appeared at Baetulo (Badalona) before the end of the 2nd century. It was not until the period of Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus, however, that full-scale Roman-style foundations (coloniae) were established for the benefit of Roman legionary veterans, some on already-existing native towns (as at Tarraco) and some on sites where there was relatively small-scale habitation previously, as at Emerita Augusta. By the early 1st century ce, there were nine such foundations in Baetica, eight in Tarraconensis, and five in Lusitania..E.B.[2]

During 170 years of conquests, the Roman Republic slowly expanded its control over all Hispania. This was a gradual process of pacification, rather than the result of a policy of conquest. In this period, conquest was a process of assimilation of the local tribes into the Roman world and its economic system after pacification. One of the main ways of assimilation was through the settlement of Romans in the peninsula.

The Romans deployed eight legions for the wars of conquest. Many of the veterans, who had the right to be granted a plot of land to farm on discharge, were settled in Hispania. Several Roman towns were founded: Augusta Emerita (Merida, Extremadura) in 25 BCE (it became the capital of the province of Hispania Lusitania; it was probably founded by Publius Carusius); Asturica Augusta (Astorga, province of Leon) in 14 BCE (it became an important administrative centre); Colonia Caesar Augusta or Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza, Aragón) in 14 BCE; and Lucus Augusti (Lugo, Galicia) in 13 BCE (it was the most important Roman town in Gallaecia). The Roman presence had probably increased during the first century BCE as a number of Roman colonies were founded in this period: Colonia Clunia Sulpicia (in the province of Burgos, it was one of the most important Roman cities of the northern half of Hispania), Cáparra (in the north of Extremadura), Complutum (Alcalá de Henares near Madrid).

In what is now Portugal there were 5 Roman colonies[3] (Emerita Augusta (Mérida, Spain), Pax Iulia (Beja), Scalabis (Santarém), Norba Caesarina and Metellinum). Felicitas Iulia Olisipo (Lisbon, which was a Roman law municipality) and 3 other Portuguese towns had the old Latin status[4] (Ebora (Évora), Myrtilis Iulia (Mértola) and Salacia (Alcácer do Sal).

Augustus also commissioned the via Augusta (which went from the Pyrenees all the way to Cadiz, it was 1,500 kilometres or 900 miles long).

Municipalities

Although Roman influence had a major impact on existing cities on the peninsula, the largest urban development effort focused on the new cities under construction, Tarraco (modern Tarragona), Emerita Augusta (now Mérida) and Italica (in the present day Santiponce, near Seville).

Roman towns or settlements were conceived as images of the imperial capital in miniature. The construction of public buildings was carried out by the curator operatum and were run directly by the supreme municipal magistrates.

To undertake any work by public funds, authorization from the emperor was needed. Patriotism and local euergetism encouraged local cities to compete, creating more affluent neighboring municipalities.

Public works undertaken with private funds were not subject to the requirement of approval of the emperor. The planners decided the space needed for the houses, plazas and temples, the volume of water required and the number and width of streets. Soldiers collaborated in the construction of the city, as well as local craftsmen together with slaves owned by patricians or equestrians.

Tarraco

Tarraco had its origin in the Roman military camp established by the two brothers, consular, Gnaeus and Publius Cornelius Scipio in 218 BC, when commanding the landing on the Iberian Peninsula during the Second Punic War. The first mention of the city is by Pliny the Elder where he characterizes the city as scipionum opus, "work of Scipio" ( Nat.Hist. III.21, and ends "... sicut Poenorum Carthago ).

In fact, Tarraco was the capital at the outset of the Hispania Citerior during the Roman Republic, and later the very extensive Hispania Citerior Tarraconensis Province. Possibly around the year 45BC. Julius Caesar changed the status of city to a colonia, which is reflected in the epithet Iulia in its formal name: Colonia Iulia Urbs Triumphalis Tarraco, which would remain for the duration of the Empire.

Emerita Augusta

.JPG.webp)

Emerita Augusta was founded in 25BC. by Publius Carisio, as the representative of the emperor Octavian Augustus as a resting place for troops discharged from the Legions V (Alaudae) and X (Gemina). Over time, this city became one of the most important in Hispania, capital of the province of Lusitania and an economic and cultural center.

Italica

Italica (located today where the city of Santiponce in the province of Seville stands) was the first purely Roman city founded in Hispania. After the Second Punic War, Scipio "Africanus" divided land between the Roman legions in the Betis river valley (now the Guadalquivir), so that although Italica was created as a field hospital for the wounded from the Battle of Ilipa, later it became a settlement for veterans of war and then a municipality, on the west bank of the river Betis in 206 BC.

It was during the time of Caesar Augustus when Italica gained the status of municipality, with the right to issue currency, but it came to its zenith during the reigns of the Caesars Trajan and Hadrian at the end of the century and during the 2nd century. They originated from Italica, which would give great prestige to the former Spanish colony in Rome. Both emperors were particularly generous to their hometown, expanding and revitalizing its economy. Hadrian ordered the construction of the nova urbs, the new city, a city that only had slight activity over the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC.

Also during the reign of Hadrian, the city changed its status to become a Roman colony. It is at this time renamed Colonia Aelia Augusta Italica, in honor of the emperor. By then, the Roman Senate had an important pressure group originating from the Spanish city.

Carthago Nova

Founded around the year 227 BC. by the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal the Fair under the name of Qart Hadast ('New Town'). It was strategically located in a large natural harbor from which the nearby silver mines of Carthago Nova could be controlled. It was taken by the Roman general Scipio Africanus in the year 209BC. during the Second Punic War to cut off the silver going to general Hannibal .

In the year 44 BC. The city would receive the title of colony under the name Colonia Iulia Urbs Nova Carthago (CVINC), founded by citizens of Roman law. Augustus in 27BC. decided to reorganize Hispania and the city was included in the new imperial province Tarraconensis, through Tiberius and Claudius, it was made the capital of conventus iuridicus Carthaginensis.

During the reign of Augustus, the city was subjected to an ambitious development program which included, among other urban developments, the construction of an impressive Roman theater, the Augusteum (imperial cult building) and a forum .

Later, under Emperor Diocletian, it was made the capital of the Roman Province Carthaginensis, separate from Tarraconensis

Military projects

The military works were the first type of infrastructure built by the Romans in Hispania, due to the confrontation on the peninsula with the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War.

Camps

The Roman fort was the main focus of military strategy passive or active. They could be constructed for short term temporary occupation, tasked with some immediate military purpose, or for garrisoning the troops during the winter, in these cases is built with mortar and wood. They could also be permanent, in order to subdue or control an area in the long term, for which stone was often used to build fortifications. Many camps became stable population centers, eventually becoming real cities, as is the case of León.

Walls

Once a developed into a stable colony or camp, the need to defend these nuclei involved the construction of powerful walls. The Romans inherited the poliorcetic tradition (siege warfare tactics) of the Greeks, and over the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, erected substantial walls, usually with the technique of double facing stones with a filling inside of mortar, stone and unique Roman concrete. The thickness of this could range from four to even ten meters. After the period of the Pax Romana these defenses were expendable, but the invasions of Germanic tribes revived the construction of walls.

There are notable present day remains of Roman walls in Zaragoza, Lugo, León, Tarragona, Astorga, Córdoba, Segóbriga and Barcelona.

Civil projects

The ancient Roman civilization is known as the great builder of infrastructure. It was the first civilization which dedicated itself to a serious and determined effort for this kind of civil work as a basis for settlement of their populations, and the preservation of its military and economic domination over the vast territory of its empire. The works of most importance are roads, bridges and aqueducts.

Infrastructure

Either within or outside the urban environment, these facilities became vital for the function of the city and its economy, allowing it to supply the most essential necessities; either water via aqueducts or food, supplies and goods through the efficient network of roads. In addition, any city of at least average importance had a sewer system for the drainage of waste water and to prevent rain flooding the streets.

Roman streets and roads

Infrastructure for civilian use was built with intensity by the Romans in Hispania, Roman roads that ran through the peninsula joining Cadiz to the Pyrenees and Asturias to Murcia: covering the coastal Mediterranean and Atlantic through the already established routes. Along them a booming trade flowed, encouraging political stability of the territory over several centuries.

Among these roads, the most important were:

- Vía Lata, now known as Vía de la Plata; or the Silver Way

- Via Augusta, the longest Imperial Roman road in Spain. 1500 km in length and comprising multiple sections

- Vía Exterior

To signal distance along these routes milestones were placed, which were either columns or significant stones, and they marked the distance from the point of origin as measured by thousands of steps (miles).

Currently most of these routes correspond to the layout of present day roads or highways in the states of Spain and Portugal, which confirms the renewed logic of the Roman optimal choice for their roads.

Bridges

Roman bridges, an essential complement to the roads, allowed them to overcome the obstacle posed by rivers, which in the case of the Iberian Peninsula can be very wide. Rome, faced with this geographical challenge, responded with some of the most durable and reliable constructions. Rome also built a large number of wooden bridges on minor crossings, but today the only surviving references are those made of stone.

The typical Roman bridge consisted of a platform supported by arches, semicircles or segments of circles. There are also cases of bridges over full circles. The pillars in the water include a wedge-shaped structures called abutments to redirect the flow of water, which create a pier on which the bridge itself sits.

This successful model construction model lasted until late Middle Ages, and today it is difficult to know in some cases if some bridges are actually Roman or if they were built later to the original design.

Aqueducts

An important town needed a constant water supply for the thousands of people gathered in one place which could be sometimes several miles away from natural water source. To achieve this continuous flow of water the Romans built aqueducts.

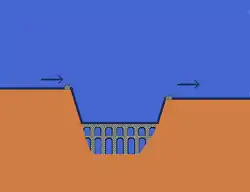

The Roman aqueducts, despite their appearances, were built mostly underground. However, they are now known as the monumental aqueducts built to bridge geographic barriers in order to give a continuous water channel. The slenderness of this type of construction, along with the tremendous height reached by some of them, makes them the most beautiful works of civil engineering of all time, especially taking into account the difficulties overcome to build them.

For the construction of an aqueduct, first they needed a source of the water, channeling a natural flow through the construction of a canal, and allowing the slope to carry water through this channel to an artificial lake (in some cases a large stone reservoir structure). This ensured the constant supply of water throughout the year.

From this point, the water could be transported by canals, whether of stone, or by pipes of ceramic or lead. The latter solution would also bring about health problems such as lead poisoning, a problem that would extend almost to the present day in places where this type of water management has been used in abundance. Lead piping was more easy to work, but was used more in the urban distribution network due to its high price, as well as aqueduct traps.

The artificial reservoir water was transported through an underground channel to the town, often taking advantage of natural slopes, but sometimes the Romans also built traps, which allowed them to avoid a downward slope without building the famous bridges but keeping the pressure flow. These traps take advantage of the pressure resulting from the falling water to raise the other side, keeping the pressure at the expense of losing some of the flow. This is an application of the principle of communicating vessels.

Current aqueducts which are notable for their condition include the first aqueduct of Segovia, which is the most famous Roman construction of the Iberian Peninsula, followed by the aqueduct in Tarragona or Devil's Bridge, and also the remains of the aqueduct of Merida, known as the Miraculous Aqueduct.

Urban works

Within the urban environment are the baths and sewers, but also remarkable buildings for leisure and culture, including theaters, circuses and amphitheaters.

Bathhouses

Roman culture worshiped the body, and therefore the health of it. The hot springs or public baths became meeting places for people from all walks of life, and their use was encouraged by the authorities, which sometimes covered their expenses which allowed free access to the population. Although men and women sometimes shared the same spaces, bath times were different for each: women came in the morning while the men did at dusk. Those available in separate sections for men and women, the separate areas devoted to them were given the name spas.

In the Iberian Peninsula there is great diversity of such archaeological buildings, highlighting their conservation status such as the Baths of Alange near Merida which, after several restorations over the 18th and 19th centuries, are now open the public as part of a medicinal water spa.

The Roman bath is a structure defined by its function, as shown in the schematic diagram of Azaila . The apodyterium was also the entrance to the baths, which also acted as a locker room. Then it led to another room called tepidarium which consisted of a warm room which in turn gave way to frigidarium or the caldearium rooms, hot and cold water respectively. The hot water rom caldearium was oriented to the south to receive the maximum amount of sunlight. Under the floor of this room was a series of pipes through which hot water circulated, or in smaller bathhouses they used a more residential style of hypocaust heating. The frigidarium, however, used to be an open pool of cool water.

Generally, the spa is surrounded by gardens and other accessory buildings with services for visitors such as gymnasiums, libraries or other places of assembly (laconium), all with the aim of providing customers with a pleasant and invigorating environment. These springs require large numbers of staff to operate, particularly taking into account the need for large amounts of hot water, the need for materials and to properly serve customers.

Sewers

The Romans knew from the beginning of its rise as a civilization that a city must have an efficient system of waste disposal in order to grow. Hence, they built in all cities of any importance the sewage systems that still in some cases remain in their original form. In Merida, for example, the Roman sewer system has been used until recent years, and its design still serves as reference to know what was the layout of the ancient Roman city. In other cities like León (founded as a camp of the Legio VII Gemina) are vestiges of these infrastructures and serve as an example on rainy days of a perfect drainage system to prevent flooded streets .

Theatres

Classical literature, both Greek and Roman, is full of dramas written expressly for public performance, although in reality, the Roman theater has its origins in the Etruscan foundations of their culture. It is however true that very soon assimilated the characteristics of ancient Greek tragedy and comedy.

The theater was one of the favorite leisure activities of the Hispanic-Roman, and as with other buildings of public interest, any city of renown could do without owning one. So much so that the theater of Emerita Augusta was built almost at the same time as the rest of the city by the consul Marcus Agrippa, son of the emperor Octavian Augustus. In total there are known remains of at least thirteen Roman theaters throughout the peninsula.

The Roman theatre had more important activities than comedies or dramas; it was a venue for celebrations that praised the emperor, it is therefore of a more political, not leisurely nature, although on occasion it may have accommodated all kinds of cultural exhibitions. The vast wealth of theaters in Hispania has to do with the political life of cities and towns which all aspired to have its own theater and therefore solidify their status.

Other examples are in the city of Baelo Claudia, a city that has an impressive Roman theatre inside the fortress, occupying a huge space. Its construction in a city where only houses have been found only within the fortress, suggests the importance of this civil building: to represent the political force of the emperor. Undoubtedly, the best preserved theater in the Peninsula is to Merida, but also the theater of Italica, Sagunto, Clunia, Caesaraugusta and others are part of the archaeological record, and some even host modern theater festivals regularly: they can be considered to be fulfilling the purpose for which they were built, in some cases more than two thousand years ago.

In the nineties Roman Theatre in Cartagena was discovered and currently under restoration.

The reconstruction carried out on Sagunto's theater, designed by architects Giorgio Grassi and Manuel Portaceli and carried out between 1983 and 1993 is still mired in both controversy and in legal disputes. A court order requires the demolition of all the reconstruction work and for the return of the theatre to the conditions in which it was before the work was conducted. It seems unlikely however that such a sentence can be executed, since it can not guarantee the preservation of the original theatre due to the scale of the necessary demolition work.

Amphitheatres

Roman culture had distinct values on human life which are very different from those now prevailing in Europe and, in general, in the world. The system of slavery, made it possible for a man to lose his status as "free man" for various reasons such as: crime, debt or military defeat. After losing their rights, they were coerced into participating in a form of entertainment which today could be considered excessively brutal, but which at that time was one of the most powerful attractions of urban life: gladiatorial combat. Not only slaves or prisoners were involved in these kinds of struggles (although the vast majority of gladiators were), but some also had career as a gladiator who fought for money, favors or glory. Even some emperors occasionally ventured down to the sand to play this bloody "sport", as in the case of the emperor Commodus.

The fight took place at first in the circus, but then the construction of amphitheatres began: elliptical buildings exclusively for the fight. The first stone amphitheater built in Rome, and the same design was later exported to major cities throughout the empire. Under the arena of the amphitheater was the pit, where gladiators and wild beasts were prepared or were locked away until the time of the fight. This pit was covered by a wooden roof on which was the scene of the fighting. Around this surface were raised elliptical arena benches where the audience attending the "games" would be situated. These arenas would also be witnesses from the 1st century onwards, of brutal repression at certain times which was exerted against the growing Christian population by the Roman authorities. Undoubtedly, the Colosseum in Rome is the best known and most monumental amphitheater in the world, but within Hispania, several were built whose remains have been preserved, such as Italica, Jerez, Tarragona and Merida.

Overview

Roman influence gradually spread across the peninsula over a prolonged period of two centuries. Many Iberian tribes were initially aggressive, opposing Roman dominion militarily, though others became allied or tributary entities increasingly reliant on Rome.

The Mediterranean coast, which was inhabited before the arrival of the Romans by indigenous Iberians such as the Turdetani and Ilergetians, as well as Greek and Phoenician/Carthaginian colonies, were quick to adopt aspects of Roman culture. The first Roman cities were founded in these territories, such as Tarraco in the northeast or Italica in the south during the period of confrontation with Carthage.

In the interior of the Iberian Peninsula, where Celtiberian, Cantabrian and Vasconian (Basque) cultures were well established. Constant military campaigns against the rebellious indigenous Iberians eventually pacified the Hispanic provinces, ending with the Augustan campaigns against the Cantabrians and Astures. The predominance of native Iberian culture diminished in the face of the cultural impact of Roman dominion, being assimilated and transformed gradually into the later Hispano-Roman culture.

The new Hispano-Roman elite, formed of the preceding Iberian tribal elite and the growing Roman aristocracy, occupied administrative positions in the new municipal institutions and wider imperial bureaucracy, serving in judicial, military and civil offices. The expansion of Roman citizenship in the Antonine Constitution in 212 AD radically changed the concept of romanitas and aided in the further assimilation of native Iberian cultures. Three Roman emperors, Theodosius I, Trajan and Hadrian, came from the Roman provinces of Hispania, as did the authors Quintilian, Martialis, Lucan and Seneca.

One of the main consequences of the romanization of Hispania was the development and use of the Spanish language and the Portuguese language after the fall of the Western Roman empire in the fifth century. These worldwide important languages evolved from Vulgar Latin, which was brought to the Iberian Peninsula by the Romans during the Second Punic War, beginning in 210 BC.

See also

Notes

- Theodore Mommsen.The Provinces of the Roman Empire from Caesar to Diocletian. Chapter: Hispania

- Spain Romanization

- Bowman, Alan K; Champlin, Edward; Lintott, Andrew (1996-02-08). The Cambridge Ancient History. ISBN 9780521264303.

Bibliography

- Appian, The Roman History (Volume I: The Foreign Wars), Digireads.com, 2011; ISBN 978-1420940374

- Curchin, L. A., Roman Spain: Conquest and Assimilation, Barnes & Nobles, 1995; ISBN 978-0415740319

- Develin, R., The Roman command structure in Spain, Klio 62 (1980) 355-67

- Errington, R. M., Rome and Spain before the second Punic War,Latomus 29 (1970) 25–57

- Knapp, R.C., Aspects of the Roman Experience in Iberia 206–100 BC, Universidad, D.L, 1977; ISBN 978-8460008149

- Mommsen, Theodor. History of Rome: Volume 4 (1908) online edition

- Mommsen, Theodor. The Provinces of the Roman Empire ("History of Rome: volume 5"). Chapter: "Hispania". Barnes & Noble ed. New York, 2005

- Nostrand, J, J, van, Roman Spain, in Tenney, F., (Ed.), An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome, Octagon Books, 1975; ISBN 978-0374928483

- Richardson, J. S. The Romans in Spain, John Wiley & Sons, Reprint edition, 1998; ISBN 978-0631209317

- Sutherland, C.. H, V, The Romans In Spain, 217 B.C.to A.D. 117, Methuen Young Books, 1971; ISBN 978-0416607000

- Wintle, Justin. The Rough Guide History of Spain, Rough Guides, 1st edition, 2003; ISBN 978-1858289366