Johannes Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer (/vɜːrˈmɛər, vɜːrˈmɪər/ vur-MEER, vur-MAIR, Dutch: [vərˈmeːr], see below; October 1632 – December 1675) was a Dutch Baroque Period[3] painter who specialized in domestic interior scenes of middle class life. During his lifetime, he was a moderately successful provincial genre painter, recognized in Delft and The Hague. Nonetheless, he produced relatively few paintings and evidently was not wealthy, leaving his wife and children in debt at his death.[4]

Johannes Vermeer | |

|---|---|

Detail of the painting The Procuress (c. 1656), believed to be a self portrait by Vermeer[1] | |

| Born | October 1632 |

| Died | December 1675 (aged 42–43) Delft, Holland, Dutch Republic |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | 34 works universally attributed[2] |

| Movement | Dutch Golden Age Baroque |

Vermeer worked slowly and with great care, and frequently used very expensive pigments. He is particularly renowned for his masterly treatment and use of light in his work.[5]

"Almost all his paintings," Hans Koningsberger wrote, "are apparently set in two smallish rooms in his house in Delft; they show the same furniture and decorations in various arrangements and they often portray the same people, mostly women."[6]

His modest celebrity gave way to obscurity after his death. He was barely mentioned in Arnold Houbraken's major source book on 17th-century Dutch painting (Grand Theatre of Dutch Painters and Women Artists) and was thus omitted from subsequent surveys of Dutch art for nearly two centuries.[7][8] In the 19th century, Vermeer was rediscovered by Gustav Friedrich Waagen and Théophile Thoré-Bürger, who published an essay attributing 66 pictures to him, although only 34 paintings are universally attributed to him today.[2] Since that time, Vermeer's reputation has grown, and he is now acknowledged as one of the greatest painters of the Dutch Golden Age.

Similar to other major Dutch Golden Age artists such as Frans Hals and Rembrandt, Vermeer never went abroad. Also, like Rembrandt, he was an avid art collector and dealer.

Pronunciation of name

In Dutch, Vermeer is pronounced [vərˈmeːr], and Johannes Vermeer as [joːˈɦɑnəs fərˈmeːr], with the /v/ changed to an [f]-sound by the preceding voiceless /s/. The usual English pronunciation is /vɜːrˈmɪər/ vur-MEER.[9][10][11] An attempt to closer approximate the Dutch with /vɜːrˈmɛər/ vur-MAIR is also heard.[10][11] A third pronunciation, /vɛərˈmɪər/ vair-MEER, is attested from the UK.[12]

Life

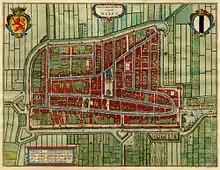

Relatively little was known about Vermeer's life until recently.[13] He seems to have been devoted exclusively to his art, living out his life in the city of Delft. Until the 19th century, the only sources of information were some registers, a few official documents, and comments by other artists; for this reason, Thoré-Bürger named him "The Sphinx of Delft".[14] John Michael Montias added details on the family from the city archives of Delft in his Artists and Artisans in Delft: A Socio-Economic Study of the Seventeenth Century (1982).

Youth and heritage

Johannes Vermeer was baptized within the Reformed Church on 31 October 1632.[15][16][lower-alpha 1] His mother, Digna Baltens (c. 1596 – 1670[20][21][22]),[lower-alpha 2] was from Antwerp.[23][24][25][18][22] Digna's father, Balthasar Geerts,[21] or Gerrits,[22] (born in Antwerp in or around 1573)[21] led an enterprising life, and was arrested for counterfeiting.[21][18] Vermeer's father, named Reijnier Janszoon, was a middle-class worker of silk or caffa (a mixture of silk and cotton or wool).[Note 1] He was the son of Jan Reyersz and Cornelia (Neeltge) Goris.[lower-alpha 3] As an apprentice in Amsterdam, Reijnier lived on fashionable Sint Antoniesbreestraat, a street with many resident painters at the time. In 1615, Reijnier married Digna. The couple moved to Delft and had a daughter named Gertruy who was baptized in 1620.[Note 2] In 1625, Reijnier was involved in a fight with a soldier named Willem van Bylandt who died from his wounds five months later.[27] Around this time, Reijnier began dealing in paintings. In 1631, he leased an inn, which he called "The Flying Fox". In 1635, he lived on Voldersgracht 25 or 26. In 1641, he bought a larger inn on the market square, named after the Flemish town "Mechelen". The acquisition of the inn constituted a considerable financial burden.[Huerta 1] When Reijnier died in October 1652, Vermeer took over the operation of the family's art business.

Marriage and family

In April 1653, Johannes Reijniersz Vermeer married a Catholic woman, Catharina Bolenes (Bolnes).[28] The blessing took place in the quiet nearby village of Schipluiden. Vermeer's new mother-in-law Maria Thins was significantly wealthier than him, and it was probably she who insisted that Vermeer convert to Catholicism before the marriage on 5 April.[Note 3] According to art historian Walter Liedtke, Vermeer's conversion seems to have been made with conviction.[28] His painting The Allegory of Faith,[29] made between 1670 and 1672, placed less emphasis on the artists' usual naturalistic concerns and more on symbolic religious applications, including the sacrament of the Eucharist. Walter Liedtke in Dutch Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art suggests that it was made for a learned and devout Catholic patron, perhaps for his schuilkerk, or "hidden church".[Liedtke 1] At some point, the couple moved in with Catharina's mother, who lived in a rather spacious house at Oude Langendijk, almost next to a hidden Jesuit church.[Note 4] Here Vermeer lived for the rest of his life, producing paintings in the front room on the second floor. His wife gave birth to 15 children, four of whom were buried before being baptized, but were registered as "child of Johan Vermeer".[Montias 1] The names of 10 of Vermeer's children are known from wills written by relatives: Maertge, Elisabeth, Cornelia, Aleydis, Beatrix, Johannes, Gertruyd, Franciscus, Catharina, and Ignatius.[Montias 2] Several of these names carry a religious connotation, and the youngest (Ignatius) was likely named after the founder of the Jesuit order.[Note 5][Note 6]

Career

It is unclear where and with whom Vermeer apprenticed as a painter. There is some speculation that Carel Fabritius may have been his teacher, based upon a controversial interpretation of a text written in 1668 by printer Arnold Bon. Art historians have found no hard evidence to support this.[Montias 3] Local authority Leonaert Bramer acted as a friend, but their style of painting is rather different.[30] Liedtke suggests that Vermeer taught himself using information from one of his father's connections.[Liedtke 2] Some scholars think that Vermeer was trained under Catholic painter Abraham Bloemaert. Vermeer's style is similar to that of some of the Utrecht Caravaggists, whose works are depicted as paintings-within-paintings in the backgrounds of several of his compositions.[Note 7]

On 29 December 1653, Vermeer became a member of the Guild of Saint Luke, a trade association for painters. The guild's records make clear that Vermeer did not pay the usual admission fee. It was a year of plague, war, and economic crisis; Vermeer was not alone in experiencing difficult financial circumstances. In 1654, the city suffered the terrible explosion known as the Delft Thunderclap, which destroyed a large section of the city.[31] In 1657, he might have found a patron in local art collector Pieter van Ruijven, who lent him some money. It seems that Vermeer turned for inspiration to the art of the fijnschilders from Leiden. Vermeer was responding to the market of Gerard Dou's paintings, who sold his paintings for exorbitant prices. Dou may have influenced Pieter de Hooch and Gabriel Metsu, too. Vermeer also charged higher than average prices for his work, most of which were purchased by an unknown collector.[32]

The influence of Johannes Vermeer on Metsu is unmistakable: the light from the left, the marble floor.[34][35][36] (A. Waiboer, however, suggests that Metsu requires more emotional involvement of the viewer.) Vermeer probably competed also with Nicolaes Maes, who produced genre works in a similar style. In 1662, Vermeer was elected head of the guild and was reelected in 1663, 1670, and 1671, evidence that he (like Bramer) was considered an established craftsman among his peers. Vermeer worked slowly, probably producing three paintings a year on order. Balthasar de Monconys visited him in 1663 to see some of his work, but Vermeer had no paintings to show. The diplomat and the two French clergymen who accompanied him were sent to Hendrick van Buyten, a baker who had a couple of his paintings as collateral.

In 1671, Gerrit van Uylenburgh organised the auction of Gerrit Reynst's collection and offered 13 paintings and some sculptures to Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg. Frederick accused them of being counterfeits and had sent 12 back on the advice of Hendrick Fromantiou.[37] Van Uylenburg then organized a counter-assessment, asking a total of 35 painters to pronounce on their authenticity, including Jan Lievens, Melchior de Hondecoeter, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, and Johannes Vermeer.

Wars and death

In 1672, a severe economic downturn (the "Year of Disaster") struck the Netherlands, after Louis XIV and a French army invaded the Dutch Republic from the south (known as the Franco-Dutch War). During the Third Anglo-Dutch War, an English fleet and two allied German bishops attacked the country from the east, causing more destruction. Many people panicked; courts, theaters, shops and schools were closed. Five years passed before circumstances improved. In 1674, Vermeer was listed as a member of the civic guards.[38] In the summer of 1675, Vermeer borrowed 1,000 guilders in Amsterdam from Jacob Romboutsz, an Amsterdam silk trader, using his mother-in-law's property as a surety.[39][40]

In December 1675, Vermeer died after a short illness. He was buried in the Protestant Old Church on 15 December 1675.[Note 8][Note 9] In a petition to her creditors, his wife later described his death as follows:

...during the ruinous war with France he not only was unable to sell any of his art but also, to his great detriment, was left sitting with the paintings of other masters that he was dealing in. As a result and owing to the great burden of his children having no means of his own, he lapsed into such decay and decadence, which he had so taken to heart that, as if he had fallen into a frenzy, in a day and a half he went from being healthy to being dead.[41]

Catharina Bolnes attributed her husband's death to the stress of financial pressures. The collapse of the art market damaged Vermeer's business as both a painter and an art dealer. She had to raise 11 children and therefore asked the High Court to relieve her of debts owed to Vermeer's creditors.[Montias 1] Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who worked for the city council as a surveyor, was appointed trustee.[42] The house had eight rooms on the first floor, the contents of which were listed in an inventory taken a few months after Vermeer's death.[43] In his studio, there were two chairs, two painter's easels, three palettes, 10 canvases, a desk, an oak pull table, a small wooden cupboard with drawers, and "rummage not worthy being itemized".[Montias 4] Nineteen of Vermeer's paintings were bequeathed to Catharina and her mother. The widow sold two more paintings to Hendrick van Buyten to pay off a substantial debt.[44]

Vermeer had been a respected artist in Delft, but he was almost unknown outside his hometown. A local patron named Pieter van Ruijven had purchased much of his output, which reduced the possibility of his fame spreading.[Note 10] Several factors contributed to his limited body of work. Vermeer never had any pupils, though one scholar has suggested that Vermeer taught his eldest daughter Maria to paint.[45] Additionally, his family obligations with so many children may have taken up much of his time, as would acting as both an art-dealer and inn-keeper in running the family businesses. His time spent serving as head of the guild and his extraordinary precision as a painter may have also limited his output.

Style

Vermeer may have first executed his paintings tonally like most painters of his time, using either monochrome shades of grey ("grisaille") or a limited palette of browns and greys ("dead coloring"), over which he would apply more saturated colors (reds, yellows and blues) in the form of transparent glazes. No drawings have been positively attributed to Vermeer, and his paintings offer few clues to preparatory methods.

There is no other 17th-century artist who employed the exorbitantly expensive pigment lapis lazuli (natural ultramarine) either so lavishly or so early in his career. Vermeer used this in not just elements that are naturally of this colour; the earth colours umber and ochre should be understood as warm light within a painting's strongly lit interior, which reflects its multiple colours onto the wall. In this way, he created a world more perfect than any he had witnessed.[Liedtke 3] This working method most probably was inspired by Vermeer's understanding of Leonardo's observations that the surface of every object partakes of the colour of the adjacent object.[46] This means that no object is ever seen entirely in its natural colour.

A comparable but even more remarkable, yet effectual, use of natural ultramarine is in The Girl with the Wine Glass. The shadows of the red satin dress are underpainted in natural ultramarine,[47] and, owing to this underlying blue paint layer, the red lake and vermilion mixture applied over it acquires a slightly purple, cool and crisp appearance that is most powerful.

Even after Vermeer's supposed financial breakdown following the so-called rampjaar (year of disaster) in 1672, he continued to employ natural ultramarine generously, such as in Lady Seated at a Virginal. This could suggest that Vermeer was supplied with materials by a collector, and would coincide with John Michael Montias’ theory that Pieter van Ruijven was Vermeer's patron.

Vermeer's works are largely genre pieces and portraits, with the exception of two cityscapes and two allegories. His subjects offer a cross-section of seventeenth-century Dutch society, ranging from the portrayal of a simple milkmaid at work, to the luxury and splendour of rich notables and merchantmen in their roomy houses. Besides these subjects, religious, poetical, musical, and scientific comments can also be found in his work.

Painting materials

One aspect of his meticulous painting technique was Vermeer's choice of pigments.[48] He is best known for his frequent use of the very expensive ultramarine (The Milkmaid), and also lead-tin-yellow (A Lady Writing a Letter), madder lake (Christ in the House of Martha and Mary), and vermilion. He also painted with ochres, bone black and azurite.[49] The claim that he utilized Indian yellow in Woman Holding a Balance[50] has been disproven by later pigment analysis.[51]

In Vermeer's oeuvre, only about 20 pigments have been detected. Of these 20 pigments, seven principal pigments which Vermeer commonly employed include lead white, yellow ochre, vermilion, madder lake, green earth, raw umber, and ivory or bone black.[52]

Theories of mechanical aid

Vermeer's painting techniques have long been a source of debate, given their almost photorealistic attention to detail, despite Vermeer's having had no formal training, and despite only limited evidence that Vermeer had created any preparatory sketches or traces for his paintings.[53]

In 2001, British artist David Hockney published the book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, in which he argued that Vermeer (among other Renaissance and Baroque artists including Hans Holbein and Diego Velázquez) used optics to achieve precise positioning in their compositions, and specifically some combination of curved mirrors, camera obscura, and camera lucida. This became known as the Hockney–Falco thesis, named after Hockney and Charles M. Falco, another proponent of the theory.

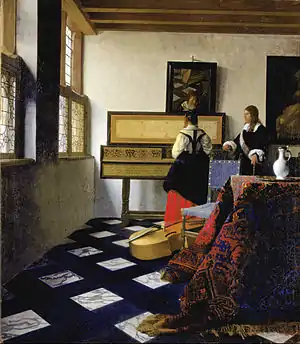

Professor Philip Steadman published the book Vermeer's Camera: Uncovering the Truth behind the Masterpieces in 2001 which specifically claimed that Vermeer had used a camera obscura to create his paintings. Steadman noted that many of Vermeer's paintings had been painted in the same room, and he found six of his paintings that are precisely the right size if they had been painted from inside a camera obscura in the room's back wall.[54]

Supporters of these theories have pointed to evidence in some of Vermeer's paintings, such as the often-discussed sparkling pearly highlights in Vermeer's paintings, which they argue are the result of the primitive lens of a camera obscura producing halation. It was also postulated that a camera obscura was the mechanical cause of the "exaggerated" perspective seen in The Music Lesson (London, Royal Collection).[55]

In 2008, American entrepreneur and inventor Tim Jenison developed the theory that Vermeer had used a camera obscura along with a "comparator mirror", which is similar in concept to a camera lucida but much simpler and makes it easy to match color values. He later modified the theory to simply involve a concave mirror and a comparator mirror. He spent the next five years testing his theory by attempting to re-create The Music Lesson himself using these tools, a process captured in the 2013 documentary film Tim's Vermeer.[56]

Several points were brought out by Jenison in support of this technique: first was Vermeer's hyper-accurate rendition of light falloff along the wall. Neurobiologist Colin Blakemore, in an interview with Jenison, notes that human vision cannot process information about the absolute brightness of a scene.[57] Another was the addition of several highlights and outlines consistent with matching the effects of chromatic aberration, particularly noticeable in primitive optics. Last, and perhaps most telling, is a noticeable curvature in the original painting's rendition of the scrollwork on the harpsichord. This effect matched Jenison's technique precisely, caused by exactly duplicating the view as seen from a curved mirror.

This theory remains disputed. There is no historical evidence regarding Vermeer's interest in optics, aside from the accurately observed mirror reflection above the lady at the virginals in The Music Lesson. The detailed inventory of the artist's belongings drawn up after his death does not include a camera obscura or any similar device.[58] However, Vermeer was in close connection with pioneer lens maker Antonie van Leeuwenhoek and Leeuwenhoek was his executor after death.[59]

Works

Vermeer produced a total of fewer than 50 paintings, of which 34 have survived.[60] Only three Vermeer paintings were dated by the artist: The Procuress (1656; Gemäldegalerie, Dresden); The Astronomer (1668; Musée du Louvre, Paris); and The Geographer (1669; Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt).

Vermeer's mother-in-law Maria Thins owned Dirck van Baburen's 1622 oil-on-canvas The Procuress (or a copy of it), which appears in the background of two of Vermeer's paintings. The same subject was also painted by Vermeer. Almost all of Vermeer's paintings are of contemporary subjects in a smaller format, with a cooler palette dominated by blues, yellows, and grays. Practically all of his surviving works belong to this period, usually domestic interiors with one or two figures lit by a window on the left. They are characterized by a sense of compositional balance and spatial order, unified by a pearly light. Mundane domestic or recreational activities are imbued with a poetic timelessness (e.g., Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie). Vermeer's two townscapes have also been attributed to this period: View of Delft (The Hague, Mauritshuis) and A street in Delft (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum).

A few of his paintings show a certain hardening of manner and are generally thought to represent his late works. From this period come The Allegory of Faith (c. 1670; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and The Love Letter (c. 1670; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam).

Legacy

Originally, Vermeer's works were largely overlooked by art historians for two centuries after his death. A select number of connoisseurs in the Netherlands did appreciate his work, yet even so, many of his works were attributed to better-known artists such as Metsu or Mieris. The Delft master's modern rediscovery began about 1860, when German museum director Gustav Waagen saw The Art of Painting in the Czernin gallery in Vienna and recognized the work as a Vermeer, though it was attributed to Pieter de Hooch at that time.[61] Research by Théophile Thoré-Bürger culminated in the publication of his catalogue raisonné of Vermeer's works in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1866.[62] Thoré-Bürger's catalogue drew international attention to Vermeer[63] and listed more than 70 works by him, including many that he regarded as uncertain.[62] The accepted number of Vermeer's paintings today is 34.

Upon the rediscovery of Vermeer's work, several prominent Dutch artists modelled their style on his work, including Simon Duiker. Other artists who were inspired by Vermeer include Danish painter Wilhelm Hammershoi[64] and American Thomas Wilmer Dewing.[65] In the 20th century, Vermeer's admirers included Salvador Dalí, who painted his own version of The Lacemaker (on commission from collector Robert Lehman) and pitted large copies of the original against a rhinoceros in some surrealist experiments. Dali also immortalized the Dutch Master in The Ghost of Vermeer of Delft Which Can Be Used As a Table, 1934.

Han van Meegeren was a 20th-century Dutch painter who worked in the classical tradition. He became a master forger, motivated by a blend of aesthetic and financial reasons, creating and selling many new "Vermeers" before turning himself in for forgery to avoid being charged with capital treason for collaboration with the Nazis, specifically, in selling what had been believed to be original artwork to the Nazis.[66]

On the evening of 23 September 1971, a 21-year-old hotel waiter, Mario Pierre Roymans, stole Vermeer's Love Letter from the Fine Arts Palace in Brussels where it was on loan from the Rijksmuseum as a part of the Rembrandt and his Age exhibition.[67]

In popular culture

Vermeer's reputation and works have been featured in both literature and in films. Tracy Chevalier's novel Girl with a Pearl Earring (1999), and the 2003 film of the same name, present a fictional account of Vermeer's creation of the famous painting and his relationship with the equally fictional model.

Gallery of selected works

The Girl with the Wine Glass (c. 1659), Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Brunswick, Germany

The Girl with the Wine Glass (c. 1659), Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Brunswick, Germany The Music Lesson or A Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman (c. 1662–1665), Royal Collection in London

The Music Lesson or A Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman (c. 1662–1665), Royal Collection in London Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665), considered a Vermeer masterpiece, Mauritshuis in Den Haag

Girl with a Pearl Earring (1665), considered a Vermeer masterpiece, Mauritshuis in Den Haag Girl with the Red Hat (c. 1665-1666), National Gallery of Art

Girl with the Red Hat (c. 1665-1666), National Gallery of Art Mistress and Maid (1666–67)

Mistress and Maid (1666–67) Vermeer's Art of Painting or The Allegory of Painting (c. 1666–1668), Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna

Vermeer's Art of Painting or The Allegory of Painting (c. 1666–1668), Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.jpg.webp) The Astronomer (c. 1668), Musée du Louvre in Paris

The Astronomer (c. 1668), Musée du Louvre in Paris.jpg.webp) The Geographer (1669), Städel Museum in Frankfurt am Main

The Geographer (1669), Städel Museum in Frankfurt am Main Lady Seated at a Virginal (c. 1672), National Gallery in London

Lady Seated at a Virginal (c. 1672), National Gallery in London

Notes

- Vermeer was baptized as Joannis.[17][15] Jan was the most popular version of the name among Calvinists. Joannis was a Latinazied form of Jan, which was preferred by Roman Catholics and upper-middle class Protestants.[17][15] However, Vermeer was born into a lower-middle class family.[18][19] Still, according to Montias, it is unlikely that his parents were Catholics "at this time [the time of Vermeer's baptism]," seeing that they "baptized him in the established church."[17] Throughout his life, Vermeer never used the name Jan. Nevertheless, "most Dutch authors, in the century since his rediscovery, have dubbed him Jan, perhaps unconsciously to bring him closer to the mainstream of Calvinist culture."[17][15]

- His mother was born in Antwerp. When she married Vermeer's father in 1615, she claimed to be twenty years old, but she may have "exaggerated her age by a year or so."[20] Digna's parents were married in Antwerp in 1596.

- Neeltge remarried three times, the second time shortly after Jan's death, in October 1597.[26]

- His name was Reijnier or Reynier Janszoon, always written in Dutch as Jansz. or Jansz; this was his patronym. As there was another Reijnier Jansz at that time in Delft, it seemed necessary to use the pseudonym "Vos", meaning Fox. From 1640 onward, he had changed his alias to Vermeer.

- In 1647 Geertruy, Vermeer's only sister, married a frame maker. She kept on working at the inn helping her parents, serving drinks and making beds.

- Catholicism was not a forbidden religion, but tolerated in the Dutch Republic. They were not allowed to build new churches, so services were held in hidden churches (so-called Schuilkerk). Catholics were restrained in their careers, unable to get high-rank jobs in city administration or civic guard. It was impossible to be elected as a member of the city council; therefore, the Catholics were not represented in the provincial and national assembly.

- A Roman Catholic chapel now exists at this spot.

- The parish registers of the Delft Catholic church do not exist anymore, so it is impossible to prove but likely that his children were baptized in a hidden church.

- The number of children seems inconsistent, but 11 was stated by his widow in a document to get help from the city council. One child died after this document was written.

- Identifiable works include compositions by Utrecht painters Baburen and Everdingen

- He was baptized as Joannis, but buried under the name Jan.

- When Catharina Bolnes was buried in 1688, she was registered as the "widow of Johan Vermeer".

- Van Ruijven's son-in-law Jacob Dissius owned 21 paintings by Vermeer, listed in his heritage in 1695. These paintings were sold in Amsterdam the following year in a much-studied auction, published by Gerard Hoet.

References

- "The Procuress: Evidence for a Vermeer Self-Portrait". Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- Jonathan Janson, Essential Vermeer: complete Vermeer catalogue; accessed 16 June 2010.

- Jennifer Courtney & Courtney Sanford: "Marvelous To Behold" Classical Conversations (2018)

- "Jan Vermeer". The Bulfinch Guide to Art History. Artchive. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- "An Interview with Jørgen Wadum". Essential Vermeer. 5 February 2003. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- Koningsberger, Hans. 1977. The World of Vermeer, New York: Time-Life Books.

- Barker, Emma; et al. (1999). The Changing Status of the Artist. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 199. ISBN 0-300-07740-8.

- Vermeer was largely unknown to the general public, but his reputation was not totally eclipsed after his death: "While it is true that he did not achieve widespread fame until the 19th century, his work had always been valued and admired by well-informed connoisseurs." Blankert, Albert, et al. Vermeer and his Public, p. 164. New York: Overlook, 2007, ISBN 978-1-58567-979-9

- "Vermeer, Jan". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Vermeer". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Vermeer". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Vermeer". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "Vermeer the Man and Painter". Essential Vermeer. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- "Vermeer: A View of Delft". The Economist. 1 April 2001. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- "Vermeer's Name". Essential Vermeer. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- "Digital Family Tree of the Municipal Records Office of the City of Delft". Beheersraad Digitale Stamboom. 2004. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

The painter is recorded as: Child=Joannis; Father=Reijnier Jansz; Mother=Dingnum Balthasars; Witnesses=Pieter Brammer, Jan Heijndricxsz, Maertge Jans; Place=Delft; Date of baptism=31 October 1632.

- Montias, John Michael (2018). Vermeer and His Milieu A Web of Social History. New Haven, Connecticut: Princeton University Press. p. 64–65. ISBN 9780691188591.

- "Vermeer's Life and Art". essentialvermeer 3.0. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- "Johannes Vermeer". theartstory.org. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Montias, John Michael (2018). Vermeer and His Milieu A Web of Social History. New Haven, Connecticut: Princeton University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780691188591.

- Montias, John Michael (1989). "Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History". Princeton University Press via jstor: 17-34. JSTOR j.ctv301fz1. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Vermeer's Family Tree". essentialvermeer 3.0. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Arnout Balis, Elisabeth Lauwers-Derveaux, Paul Janssens (2006). België in de 17de eeuw: deel 3. De leefwereld. Dexia Bank. p. 161.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Albert Blankert, Rob Ruurs, Willem L. van de Watering (1975). Johannes Vermeer van Delft 1632-1675. Spectrum. p. 121. ISBN 9789027483348.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "About Johannes Vermeer". Vermeer centrum Delft. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- John Michael Montias (1989). Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History. Princeton University Press. p. 35–55. ISBN 0691002894.

- John Michael Montias (1989). Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History. Princeton University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0691002894.

- Liedtke, Walter; Plomp, Michiel C.; Rüger, Axel (2001). Vermeer and the Delft school: [catalogue ... in conjunction with the exhibition "Vermeer and the Delft School" held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from 8 March to 27 May 2001, and at The National Gallery, London, from 20 June to 16 September 2001]. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 359. ISBN 0870999737.

- "Johannes Vermeer: Allegory of the Catholic Faith (32.100.18) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metmuseum.org. 20 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- "Vermeer biography". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- "Delft in Johannes Vermeer's Time", Essential Vermeer. Retrieved 29 September 2009

- Nash, J.M. (1972). The age of Rembrandt and Vermeer: Dutch painting in the seventeenth century. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. pp. 40. ISBN 9780030918704.

- Andrew Graham-Dixon, The Madness of Vermeer, BBC Four.

- Adriaan E. Waiboer, Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667): Life and Work, PhD dissertation, New York University, School of Fine Arts, 2007: ProQuest, pp. 225–30.

- "Curator in the spotlight: Adriaan E. Waiboer, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin", Codart, retrieved 12 September 2014.

- Susan Stamberg, "Gabriel Metsu: The Dutch Master You Don't Know", Morning Edition, NPR, 18 May 2011.

- Montias (1989). Vermeer and His Milieu. p. 207. ISBN 0691002894.

- "Vermeer's Delft Today: Schutterij and the Doelen", Essential Vermeer.

- John Michael Montias (1991). Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History. Princeton University Press. p. 337. ISBN 0-691-00289-4.

- "A Postscript on Vermeer and His Milieu", Auteur: John Michael Montias, Uitgever: Uitgeverij Atlas Contact B.V.

- Quoted from "Vermeer's Life and Art (part four)", Essential Vermeer.

- Snyder (2015), pp. 268–71

- "Inventory of movable goods in Vermeer's house in Delft". www.essentialvermeer.com. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Montias (1989), Vermeer and His Milieu, p. 217.

- Binstock, Benjamin. (2009). Vermeer's family secrets : genius, discovery, and the unknown apprentice. Vermeer, Johannes, 1632-1675. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96664-1. OCLC 191024081.

- B. Broos, A. Blankert, J. Wadum, A. K. Wheelock Jr. (1995) Johannes Vermeer, Waanders Publishers, Zwolle

- Gaskell, I., M. Jonker & National Gallery of Art (US) (1998), Vermeer Studies. Washington: National Gallery of Art, p. 157. ISBN 0300075219

- Kuhn, H. "A Study of the Pigments and Grounds Used by Jan Vermeer". Reports and Studies in the History of Art, 1968, 154–202

- Illustrated pigment analyses of Vermeer's paintings: Dutch Painters, Colourlex

- Kuhn, 1968, pp. 191–192

- Gifford, E.M., "Painting Light: Recent Observations on Vermeer’s Technique", in Gaskell, I. and Jonker, M., ed., Vermeer Studies, in Studies in the History of Art, 55, National Gallery of Art, Washington 1998, pp. 185–199

- Janson, Jonathan. "Vermeer's Palette". Essential Vermeer. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- Sooke, Alastair (25 April 2017). "Why Vermeer's paintings are less 'real' than we think". BBC Culture. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Steadman, Philip. "Vermeer and the Camera Obscura". BBC. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- Steadman, Philip (2017). Vermeer and the Problem of Painting Inside the Camera Obscura. Berlin/Munich/Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 76–86. ISBN 9783110547214.

- Andersen, Kurt (29 November 2013). "Reverse-Engineering a Genius (Has a Vermeer Mystery Been Solved?)". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013.

- Tim's Vermeer (2013) documentary – See 40:50 onwards

- "Vermeer and the Camera Obscura". Essential Vermeer 2.0. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- Bryson, Bill (2014). A Short History of Nearly Everything. Lulu Press. ISBN 978-1312792562.

- "Vermeer was brilliant, but he was not without influences". The Economist. 12 October 2017.

- Gaskell, Jonker & National Gallery of Art (1998). Vermeer Studies, pp. 19–20.

- Gaskell, Jonker & National Gallery of Art (1998). Vermeer Studies, p. 42.

- Vermeer, J., F. J. Duparc, A. K. Wheelock, Mauritshuis (Hague, Netherlands), & National Gallery of Art (1995). Johannes Vermeer. Washington: National Gallery of Art, p. 59. ISBN 0300065582

- Gunnarsson, Torsten (1998), Nordic Landscape Painting in the Nineteenth Century. Yale University Press, p. 227. ISBN 0300070411

- "Interpretive Resource: Artist Biography: Thomas Wilmer Dewing". Artic.edu. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Anthony Julius (22 June 2008). "The Lying Dutchman". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Janson, Jonathan. "Vermeer Thefts: The Love Letter". www.essentialvermeer.com. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

Sources

- Liedtke, Walter A. (2007). Dutch Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-300-12028-8.

- W. Liedtke, p. 893.

- W. Liedtke, p. 866.

- W. Liedtke, p. 867.

- Montias, John Michael (1991). Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (reprint, illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00289-7.

- pp. 344–345.

- pp. 370–371.

- p. 104.

- pp. 339–344.

- Huerta, Robert D. (2003). Giants of Delft: Johannes Vermeer and the Natural Philosophers: the Parallel Search for Knowledge During the Age of Discovery. Bucknell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8387-5538-9.

- pp. 42–43.

Further reading

- Liedtke, Walter (2009). The Milkmaid by Johannes Vermeer. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588393449.

- Liedtke, Walter A. (2001). Vermeer and the Delft School. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870999734.

- Kreuger, Frederik H. (2007). New Vermeer, Life and Work of Han van Meegeren. Rijswijk: Quantes. pp. 54, 218 and 220 give examples of Van Meegeren fakes that were removed from their museum walls. Pages 220/221 give an example of a non–Van Meegeren fake attributed to him. ISBN 978-90-5959-047-2. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- Singh, Iona (2012). "Vermeer, Materialism and the Transcendental in Art". from the book, Color, Facture, Art & Design. United Kingdom: Zero Books. pp. 18–40.

- Schneider, Nobert (1993). Vermeer. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag. ISBN 3-8228-6377-7.

- Sheldon, Libby; Nicola Costaros (February 2006). "Johannes Vermeer's 'Young woman seated at a virginal". The Burlington Magazine (vol. CXLVIII ed.) (1235).

- Snyder, Laura J. (2015). Eye of the Beholder: Johannes Vermeer, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, and the Reinvention of Seeing. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-07746-9.

- Steadman, Philip (2002). Vermeer's Camera, the truth behind the masterpieces. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280302-6.

- Wadum, J. (1998). "Contours of Vermeer". In I. Gaskel and M. Jonker (ed.). Vermeer Studies. Studies in the History of Art. Washington/New Haven: Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers XXXIII. pp. 201–223.

- Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. (1988) [1st. Pub. 1981]. Jan Vermeer. New York: Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-1737-8.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Johannes Vermeer |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Johannes Vermeer. |

| Library resources about Johannes Vermeer |

- 500 pages on Vermeer and Delft

- Johannes Vermeer, biography at Artble

- Essential Vermeer, website dedicated to Johannes Vermeer

- Johannes Vermeer in the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Vermeer Center Delft, center with tours about Vermeer

- Vermeer's Mania for Maps, WGBHForum, 30 December 2016

- Pigment analyses of many of Vermeer's paintings at Colourlex

- Location of Vermeer's The Little Street