Russia in the European energy sector

The Russian Federation supplies a significant volume of fossil fuels and is the largest exporter of oil, natural gas and hard coal to the European Union.[1] In 2017, energy products accounted around 60% of the EU's total imports from Russia.[2] According to Eurostat, 30% of the EU's petroleum oil imports and 39% of total gas imports came from Russia in 2017. For Estonia, Poland, Slovakia and Finland, more than 75% of their imports of petroleum oils originated in Russia.[2]

_(44636201715).png.webp)

The Russian state-owned company Gazprom exports natural gas to Europe. It also controls many subsidiaries, including various infrastructure assets. According to a study published by the Research Centre for East European Studies, the liberalization of the EU gas market has driven Gazprom's expansion in Europe by increasing its share in the European downstream market. It has established sale subsidiaries in many of its export markets, and has also invested in access to industrial and power generation sectors in Western and Central Europe. In addition, Gazprom has established joint ventures to build natural gas pipelines and storage depots in a number of European countries.[3] Transneft, a Russian state-owned company responsible for the national oil pipelines, is another Russian company that supplies energy to Europe.

In September 2012, the European Commission opened formal proceedings to investigate whether Gazprom was hindering competition in Central and Eastern European gas markets, in breach of EU competition law. In particular, the Commission looked into Gazprom's usage of 'no resale' clauses in supply contracts, alleged prevention of diversification of gas supplies, and imposition of unfair pricing by linking oil and gas prices in long-term contracts.[4] The Russian Federation responded by issuing blocking legislation, which introduced a default rule prohibiting Russian strategic firms, including Gazprom, to comply with any foreign measures or requests.[5] Compliance is subject to prior permission granted by the Russian government.

History

In the early 1980s there were American efforts, led by the Reagan administration, to convince European countries, through which a proposed Soviet gas pipeline was to be built, to deny firms responsible for construction the ability to purchase supplies and parts for the pipeline and associated facilities. Ronald Reagan feared that a Kremlin-controlled European natural gas pipeline infrastructure would increase the USSR's influence not only in Eastern Europe, but also in Western Europe. For this reason, during his first term in office, he attempted – unsuccessfully – to stop the first natural gas pipeline from being built between the USSR and Germany. The pipeline was built despite these protests and the rise of large Russian gas firms such as Gazprom as well as increased Russian fossil fuel production has facilitated a large expansion in the quantity of gas supplied to the European market since the 1990s.[6]

Natural gas deliveries

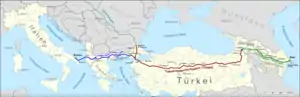

In 2017, 39% of the European Union's natural gas total imports originated in Russia.[2] As of 2009, Russian natural gas was delivered to Europe through 12 pipelines, of which three were direct pipelines (to Finland, Estonia and Latvia), four through Belarus (to Lithuania and Poland) and five through Ukraine (to Slovakia, Romania, Hungary and Poland).[7] In 2011, an additional pipeline, Nord Stream (directly to Germany through the Baltic Sea), opened.[8]

The largest importers of Russian gas in the European Union are Germany and Italy, accounting together for almost half of the EU's gas imports from Russia. Other larger Russian gas importers (over 5 billion cubic meter per year) in the European Union are France, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland, Austria and Slovakia.[9][10] The largest non-EU importers of Russian natural gas are Ukraine, Turkey and Belarus.[9]

In 2013 the shares of Russian natural gas in the domestic gas consumption in EU countries were:[11]

Estonia 100%

Estonia 100% Finland 100%

Finland 100% Latvia 100%

Latvia 100% Lithuania 100%

Lithuania 100% Slovakia 100%

Slovakia 100% Bulgaria 97%

Bulgaria 97% Hungary 83%

Hungary 83% Slovenia 72%

Slovenia 72% Greece 66%

Greece 66% Czech Republic 63%

Czech Republic 63% Austria 62%

Austria 62% Poland 57%

Poland 57% Germany 46%

Germany 46% Italy 34%

Italy 34% France 18%

France 18% Netherlands 5%

Netherlands 5%.svg.png.webp) Belgium 1.1%

Belgium 1.1%

Disputes and diversification efforts

On the eve of the 2006 Riga summit, Senator Richard Lugar, head of the U.S. Senate's Foreign Relations Committee, declared that "the most likely source of armed conflict in the European theatre and the surrounding regions will be energy scarcity and manipulation."[13] Since then, the variety of national policies and stances of larger exporters versus larger dependents of Russian gas, together with the segmentation of the European gas market, has become a prominent issue in European politics toward Russia, with significant geopolitical implications for economic and political ties between the EU and Russia. These ties have occasionally led to calls for greater European energy diversity, although such efforts are complicated by the fact that many European customers have long term legal contracts for gas deliveries despite the disputes, most of which stretch beyond 2025–2030.[14] The EU's failure to successfully advance a common energy policy can be further exemplified by the building of the Nord Stream pipeline, which embodies the divisions between the center and the periphery of the EU—between Old and New Europe.

A number of disputes over the natural gas prices in which Russia was using pipeline shutdowns in what was described as "tool for intimidation and blackmail"[15] caused the European Union to significantly increase efforts to diversify its energy sources.[16] Some have even argued that Russia has developed "the capacity to use unilateral economic sanctions in the form of gas pricing and gas disruptions against many European North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member states".[6] During an anti-trust investigation initiated in 2011 against Gazprom, a number of internal company documents were seized that documented a number of "abusive practices" in an attempt to "segment the internal [EU] market along national borders" and impose "unfair pricing".[17]

Part of the aim of the Energy Union is to diversify the EU’s gas supplies away from Russia, which has already proved to be an unreliable partner, first in 2006 and then in 2009, and which threatened to become one again at the outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine in 2013–2014.

The planned Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany was opposed by Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, U.S. President Donald Trump and British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson.[18][19] In 2017, Germany, France, Austria and European Commission criticized the United States over new sanctions against Russia that target Nord Stream 2.[20][21][22] The United States has been encouraging European countries to diversify Russian-dominated energy supplies, with Qatar as possible alternative supplier.[23]

To compare with alternative sources, Germany produced 10.5% of its electricity from fossil natural gas in 2019 and 8.6% (44 TWh) from renewable biomass, largely biogas.[24] As only 13% of Germany's gas use was for power production,[25] this replaced just above 1 percent of its overall gas consumption. Replacing natural gas with gas produced with Renewable energy in Power-to-gas processes or by direct use of power has more potential for further expansion. Power-to-gas is as yet limited to small-scale demonstration projects, as the carbon dioxide resulting from the combustion of natural gas can be emitted cheaply or for free, and Russia does not take back carbon dioxide from the combustion of Russian gas for underground storage in its depleted gas reservoirs.

In January 2020 Russia halted oil deliveries to Belarus over another price dispute.[26]

Nuclear fuel supplies

_(9776894576).jpg.webp)

Ukraine has been traditionally sourcing fuel for its nuclear power plants from Russia, although with the outbreak of Russian military intervention in Donbass it saw an urgent need to at least diversify supplies of fuel and started talks with a number of Western suppliers, most notably Westinghouse branch in Sweden. In response, Russia started an intimidation campaign which included supplying deliberately incorrect technical specifications of the existing fuel supplies, alluding to "second Chernobyl" and staging protests in Kyiv. In spite of these efforts, Ukraine secured a number of framework contracts with numerous suppliers, eventually supplying 50% of the fuel from Russia and 50% from Sweden.[27]

See also

- Energy policy of Russia

- Energy policy of the European Union

- Foreign relations of Russia

- Russian influence operations

- European countries by fossil fuel use (% of total energy)

- European countries by electricity consumption per person

- List of countries by natural gas exports

- List of countries by natural gas imports

- List of countries by natural gas proven reserves

References

- "Russia has maintained though throughout the whole period 2007-2017 its position as the leading supplier to the EU of the main primary energy commodities – hard coal, crude oil and natural gas" https://web.archive.org/web/20191019113648/https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Energy_production_and_imports

- "EU imports of energy products - recent developments" (PDF). Eurostat. 4 July 2018. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Koszalin, Andreas Heinrich (5 February 2008). "Gazprom's Expansion Strategy in Europe and the Liberalization of EU Energy Markets" (PDF). Russian Analytical Digest. Research Centre for East European Studies (34 Russian Business Expansion). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- European Commission, Antitrust: Commission Opens Proceedings Against Gazprom, IP/12/937

- Marek Martyniszyn, Legislation Blocking Antitrust Investigations and the September 2012 Russian Executive Order, 37(1) World Competition 103 (2014)

- Iftimie, Ion (22 January 2015). Natural Gas as an Instrument of Russian State Power (Second edition, fully revised and updated ed.). Washington, D.C.: Westphalia Press. p. 74. ISBN 9781633911390. OCLC 908407323.

-

"Commission staff working document–Accompanying document to the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning measures to safeguard security of gas supply and repealing Directive 2004/67/EC. Assessment report of directive 2004/67/EC on security of gas supply {COM(2009) 363}". European Commission. 16 July 2009: 33, 56, 63–76. Retrieved 30 January 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Juergen Baetz (8 November 2011). "Merkel, Medvedev inaugurate new gas pipeline". Associated Press. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

-

"Country analysis briefs: Russia" (PDF). Energy Information Administration. May 2008: 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) -

Noël, Pierre (May 2009). "A Market Between Us: Reducing the Political Cost of Europe's Dependence on Russian Gas" (PDF). EPRG Working Paper Series. University of Cambridge Electricity Policy Research Group: 2; 38. EPRG0916. Retrieved 30 January 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jones, Dave; Dufour, Manon; Gaventa, Jonathan (June 2015). "Europe's Declining Gas Demand: Trends and Facts about European Gas Consumption" (PDF). E3G. p. 9. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Germany's Angela Merkel slams planned US sanctions on Russia". Deutsche Welle. 16 June 2017.

- Energy security challenges for the 21st century : a reference handbook. Luft, Gal., Korin, Anne. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger Security International. 2009. ISBN 9780275999988. OCLC 522747390.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Simon Pirani; Jonathan Stern; Katja Yafimava (February 2009). The Russo-Ukrainian gas dispute of January 2009: a comprehensive assessment (PDF). NG 27. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-901795-85-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- Kramer, Andrew E. (27 October 2006). "Lithuania suspects Russian oil grab". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- "Europe's alternatives to Russian gas". European Council of Foreign Relations. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- "EU documents lay bare Russian energy abuse". Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Germany and Russia gas links: Trump is not only one to ask questions". The Guardian. 11 July 2018.

- "Trump barrels into Europe's pipeline politics". Politico. 11 July 2018.

- "Germany threatens retaliation if U.S. sanctions harm its firms". Reuters. 16 June 2017.

- "The U.S. Sanctions Russia, Europe Says 'Ouch!'". Bloomberg. 16 June 2017.

- "France says U.S. sanctions on Iran, Russia look illegal". Reuters. 26 July 2017.

- "U.S. wants Qatar to challenge Russian gas in Europe -U.S. official". Reuters. 14 January 2019.

- Der deutsche Strommix: Stromerzeugung in Deutschland https://strom-report.de/strom/ Retrieved 7 September 2020

- Anteil der Verbrauchergruppen am Erdgasabsatz in Deutschland in den Jahren 2009 und 2019 https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/37985/umfrage/verbrauch-von-erdgas-in-deutschland-nach-abnehmergruppen-2009/ Retrieved 7 September 2020

- "Russia turns off oil taps supplying Belarus". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Kärnfrågan". Fokus (in Swedish). 6 February 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

.jpg.webp)