Sarah Williams (Labyrinth)

Sarah Williams[4] is a fictional character and the protagonist of the 1986 fantasy film Labyrinth. Portrayed by Jennifer Connelly, Sarah is an imaginative teenager who wishes her baby brother Toby away to the goblins. To get her brother back, she is given 13 hours to solve an enormous otherworldly labyrinth and retrieve Toby from the castle of Jareth, the Goblin King (David Bowie).

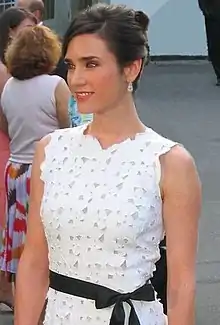

| Sarah Williams | |

|---|---|

Jennifer Connelly as Sarah in Labyrinth (1986). | |

| First appearance | Labyrinth (1986) |

| Created by | Jim Henson |

| Designed by | Brian Froud |

| Portrayed by | Jennifer Connelly |

| In-universe information | |

| Relatives |

|

| Nationality | American |

Sarah also appears in the film's adaptions, including the novelisation, Marvel comic books, storybook and photo album. She is a supporting character in the manga sequel Return to Labyrinth published by Tokyopop, and various spin-off comics published by Archaia.

Concept and creation

Labyrinth started as a collaboration between director Jim Henson and conceptual designer Brian Froud following their previous collaboration, The Dark Crystal (1982). According to Froud, they wanted to have human characters as the lead roles in order to make Labyrinth "more accessible and immediate" than The Dark Crystal, which had featured only puppets.[5] The protagonist of Labyrinth was, at different stages of its development, going to be a boy,[6] a king whose baby had been put under an enchantment, a princess from a fantasy world, and a young girl from Victorian England.[7] According to Henson, the decision to have the lead character be a girl was "because so many adventure films feature boys. We just wanted to even the balance."[8] In order to make the film more commercial, they made Sarah a teenager from contemporary America.[7] Henson stated:

"We basically wanted to make Labyrinth about the growing-up process of maturity, working with the idea of a young girl right at that point between girl and woman, shedding her childhood thoughts for adult thoughts. Specifically, I wanted to make the idea of taking responsibility for one's life — which is one of the neat realizations a teenager experiences — a central thought of the film."[7]

According to co-writer Dennis Lee, he and Henson defined two main characteristics for Sarah as being "spunky, feisty, high-spirited" and "very volatile – poised on the brink of womanhood, and capable of trying out very different versions of whom she might be". Henson also wanted her to be initially spoiled and petulant in order to allow for her character to grow out of these flaws over the course of the film.[9] Acknowledging that the character cannot experience every aspect of maturity in the course of an evening or an hour-and-a-half movie, Henson said that the film concentrates most of all on Sarah learning to take responsibility for her life as well as for her baby brother she is supervising.[10] Describing Sarah as someone "resisting growing up, clinging to her childhood,"[10] Henson noted that the character's favourite expression, "It's not fair!", is related to her initial refusal to take responsibility for her life and "merely saying that something else is to blame [for her troubles]".[11] According to Henson's eldest daughter Lisa, Sarah's personality was partly modelled on Henson's second-eldest daughter, Cheryl, who had been "very romantic in her outlook" and passionate about fantasy and theatre as a teenager.[12] Cheryl, who was a puppeteer on Labyrinth, admitted that she had inspired some aspects of the character, such as Sarah being "a little selfish, a little too smart for her own good".[13]

Between the more than twenty-five iterations of the Labyrinth screenplay, Sarah's character was continually tweaked to create a lead role that audiences would find sympathetic and be able to relate to.[14] Early production meetings gave focus to reflecting Sarah's emotional journey through the film's visuals.[15] Froud had suggested to Henson the idea of a labyrinth as a setting for the film, partly because he recognised it as symbolic of Sarah's mind due to its resemblance to a brain.[16] According to Lee, the use of graphic artist M. C. Escher's work as basis for one of the set designs (the "Escher" staircase scene) served to create a scene where Sarah is forcibly detached from her previous taken-for-granted assumptions about the reliability of her own senses and her perception of time and space.[9]

The fantasy world of the Labyrinth created for the film is centered around Sarah, with the influences of the film also being the influences of her mind.[16] According to Henson, "the world that Sarah enters exists in her imagination. The film starts out in her bedroom and you see all the books she's read growing up – The Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, the works of Maurice Sendak. The world she enters shows elements of all these stories that fascinated her as a girl".[17] Additional titles shown briefly in Sarah's room at the start of the film are Grimm's Fairy Tales, Hans Christian Andersen collection His Classic Fairy Tales, and Walt Disney's Snow White Annual.[1] The goblins that come to take her brother away, as well as Sarah's monologue that she recites to defeat the Goblin King, are from her favourite story,[18] a play called "The Labyrinth" which she rehearses at the beginning of the film.[12][19] Sarah's experiences in the Labyrinth are also reflective of the objects shown in her room.[lower-alpha 5] Many of the characters she encounters bear a resemblance to her toys, including a statuette of the Goblin King. She also has a maze-puzzle board game. The dress Sarah wears in her ballroom dream adorns a miniature doll on her music box, which also plays the same tune as in her dream. One of the obstacles that Jareth sets on Sarah recalls the "Slashing Machine" record on her shelf, and Sarah's final confrontation with the king takes place in a room that resembles her poster of Escher's Relativity.[20][21]

Some of Sarah's books and posters were those that had been childhood favourites of Henson's,[10][22] as well as reflecting his children's interests.[12] Henson said that by "plant[ing] all those things in Sarah's room as what she would dream about" they made the film "a homage to all the things we love."[23]

Casting and filming

For the lead role of Sarah, Henson sought "a girl who looked and could act that kind of dawn-twilight time between childhood and womanhood."[17] Auditions for the part began in England in April 1984. Helena Bonham Carter auditioned for the role, but was passed over in favor of an American actress. Monthly auditions were held in the United States until January 1985, and Jane Krakowski, Mary Stuart Masterson, Yasmine Bleeth, Sarah Jessica Parker, Marisa Tomei, Laura San Giacomo, Laura Dern, Ally Sheedy, Maddie Corman, and Mia Sara all auditioned for the role. Of these, Krakowski, Sheedy and Corman were considered to be the top candidates.[12][14] 150 girls had auditioned for the role in London, New York, Los Angeles and Chicago,[24] when 14-year-old actress Jennifer Connelly "won Jim [Henson] over" and he cast her within a week.[14] Recalling Connelly's audition, Henson said, "She did a terrific line-reading, then an improvisation that sent chills down my back ... she was simply a perfect actress."[23] He felt that Connelly was "exactly right" for the role as she was "just at that point in her life that Sarah was in the picture".[24] Connelly moved to England in February 1985 in advance of Labyrinth's rehearsals,[14] and spent seven months between March and September 1985 making the film at Thorn-EMI Elstree Studios in London.[25][26] She expressed that she had "always been the biggest fan of Sesame Street, so working with Mr. Henson was a dream."[26]

Discussing her understanding of her role, Connelly said that Labyrinth is "about a sort of awakening. . .a young girl growing out of her childhood, who is just now becoming aware of the responsibilities that come with growing up."[27] She explained that Sarah learns "that she can't hold onto her childhood any longer. She has to change, and she must open up to other people and other things." Connelly also related the character's development to her own experience of adolescence: "The change from child to adult doesn't feel like the same kind of on-off switch for me. It's more of a gradual progression. In some ways, I don't want to grow up, but I've always known it was going to happen. I haven't tried to stop it. In that way, Sarah and I are different."[28]

As Sarah is one of the few human characters in Labyrinth, Connelly initially found it a challenge to interact naturally with the puppets she shared many of her scenes with.[29][30] Comparing the experience to acting with animals,[22] she found the creatures easy to relate to once she thought of them as characters instead of puppets.[28] She got along well with Henson,[25] whom she felt understood her very well and "was very good at catching what [she] was feeling" due to him having a daughter the same age as her.[28] Connelly enjoyed making the film, describing the experience as "magical" and the Labyrinth set as being "like a wonderland" for her.[12][31] She found Henson's direction both creative and receptive to her ideas, saying, "He has a very positive idea of how a scene should be, but if you do something different, he'll say, 'Well, that's not what I had in mind, but I like that, too. Let's go with it.'"[28] Connelly also enjoyed working alongside her costar David Bowie, from whom she learnt "to try many things ... to have fun with [acting], and to get to the point where you know your scene so well, that when you go to the set, you can just run with it, go in all different directions."[28] Connelly completed most of her scenes in two or three takes, except for very technical scenes or those involving complex puppets.[28][32] She performed some of her own stunt work, including the "Shaft of Hands" sequence where she descended a 30-foot high shaft in a body mold attached to a hinged bar, accompanied by a camera mounted on a forty-foot vertical camera track.[28][33] While Connelly named the ballroom scene as her favourite to film,[34] she said she "had no skill whatsoever" at ballroom dancing, and had to have lessons with choreographer Cheryl McFadden.[35][36]

Costume

Brian Froud and costume designer Ellis Flyte made Sarah's main outfit a waistcoat and large white blouse which "didn't place her precisely in this world" but would look appropriate in a fairy tale world. However, they made sure she wore a pair of blue jeans in order to keep her contemporary.[16] Sarah is first introduced in the film wearing a medieval-style gown which is revealed to be a costume when her jeans are shown beneath it.[37]

In the scene of Sarah's masquerade ball fantasy, she wears a silver ballgown with puffed sleeves. The dress was made from silver lamé and iridescent rainbow paper, overlaid with lace and jewels on the bodice, and worn with a pannier beneath the skirt. Her outfit was designed with a silver and mint colour scheme to set her apart from the other people in the scene.[35] Jim Henson originally wanted Connelly's hair in ringlets for the scene, which "horrified" Froud and to which Connelly's parents disagreed, as they did not want her to appear too grown up. Froud eventually designed her hair in an "art nouveau" style with silver leaves and vines entwined at the sides, "something that was connected to nature and yet had a sophistication to it".[16]

Sarah is depicted in her ballgown on the film's promotional poster, designed and painted by Ted Coconis. Henson had insisted that Sarah be portrayed in her blue jeans; however, Coconis overrode this input as he felt it "inappropriate for the look and feeling of the painting as well as the movie itself. [Sarah] simply had to be wearing the gorgeous gown".[38]

In Labyrinth

16-year-old[39] Sarah Williams rehearses a play called "The Labyrinth" in the park with her dog Merlin but becomes distracted by a line she is unable to remember. Realizing she is late to babysit her baby half-brother Toby, she rushes home and is confronted by her stepmother before she and her father leave for dinner. She then finds Toby in possession of her treasured childhood teddy bear, Lancelot. Frustrated by this and his constant crying, Sarah rashly wishes Toby be taken away by the goblins. She is shocked when Toby disappears and Jareth, the Goblin King, arrives. He offers Sarah her dreams in exchange for the baby, but she refuses, having instantly regretted her wish. Jareth then informs Sarah that she has 13 hours to solve his labyrinth and find Toby before he is turned into a goblin forever.

Sarah progresses through the Labyrinth by solving a number of practical puzzles and riddles, plus avoiding occasional obstacles set by Jareth. During her journey she comes across a variety of unusual creatures who help her, befriending three who become her main companions: a cowardly dwarf named Hoggle, a gentle beast named Ludo and a fox-like knight named Sir Didymus.

Sarah's alliance with Hoggle irritates King Jareth, as Hoggle had been supposed to lead Sarah back to the beginning of the Labyrinth but instead helps her after she bribes him with jewellery. Under Jareth's orders, Hoggle gives Sarah an enchanted peach which causes her to temporarily forget her quest. Drawn towards one of Jareth's crystals, she is transported into a dream of a masquerade ball. There Sarah dances with Jareth as he proclaims his love for her, but she rebuffs him and escapes the dream. Falling into a junkyard, she is distracted by an old Junk Lady who offers Sarah her various childhood items. Sarah's memory returns when she finds her book "The Labyrinth" and she resumes her quest to save Toby, reuniting with her friends at the gate to the Goblin City.

After overcoming first the gate guard then the goblin army, Sarah arrives at Jareth's castle, whereupon she parts from her friends, insisting she must face Jareth alone and promising to call the others if needed. In a gravity-defying room of staircases, Sarah confronts Jareth while trying to retrieve Toby. As Jareth offers Sarah her dreams again, promising to be her slave on the condition that she fear, love and obey him, she remembers the line from her book, "You have no power over me!". She is returned home safely with Toby and watches as Jareth turns into an owl and flies away.

Realizing how important Toby is to her, Sarah gives him Lancelot and returns to her room. As her father and stepmother return home, she sees Hoggle, Ludo and Didymus in the mirror and realizes even though she is growing up, she still needs them in her life every now and again. In an instant, a number of goblins and the major characters from the Labyrinth appear in her room for a raucous celebration.

Characterisation and themes

16 years old,[39] Sarah is at the start of the film a discontent teenager who resents her father and stepmother for assuming she'll babysit her baby half-brother, Toby.[40] Playbills and various news clippings in Sarah's room reveal that her absent mother Linda Williams is a stage actress, though it is unknown to what extent Linda is absent from Sarah's life.[41] A "bookworm",[42] Sarah has a preoccupation with drama and romantic fairy tales,[43][44] and is apt to playing pretend,[40][45] using fantasy as a mental escape from her unhappy home life.[46] Rene Jordan of El Miami Herald identified Sarah as having "a Cinderella complex", believing that her stepmother mistreats her by making her look after Toby.[47] Essayist Tom Holste wrote that it is "a clever twist on traditional fairy tales" that Sarah's stepmother is "the nice one", while Sarah herself – "the "princess"" – is "insufferable".[45] Chris Cabin of Collider wrote that the rift between Sarah and her stepmother spurs the film's "anti-authoritarian mood".[48]

Rita Kempley of The Washington Post identified Sarah as "the ingénue, a resourceful young woman with a wonderful imagination, great courage and a healthy case of sibling rivalry".[49] Jessica Ellis of HelloGiggles wrote that Sarah embodies many stereotypical attributes of young women, such as being "daydreamy and forgetful...dedicat[ed] to drama," but noted that such characteristics strengthen the character since "her ability to think creatively, to empathize, comes to her rescue again and again" in the Labyrinth.[50] Sarah matures over her adventure, gradually freeing herself from childish impulses, becoming less selfish, and learning to take responsibility for her actions.[51]

— George Lucas, Labyrinth executive producer.[52]

Critics note the subtext of Labyrinth as Sarah's journey to womanhood,[53][54][55] including her sexual awakening represented by the Goblin King.[56][57][58][59] Several have noted the parallel between Sarah's relationship to Jareth and that of Sarah's actress mother to her co-star boyfriend (also depicted as Bowie),[41][60][61] writer James Gracey observing, "Sarah finds that she too is tempted to make the same choice [as her mother] and abandon her family for a fantastical romance".[62] Although Sarah initially desires freedom from her babysitting responsibilities, she comes to realise what Jareth offers her "isn’t power and freedom, but isolation and selfishness,"[63] and that escaping into a fantasy would mean ceding control over her own life.[64] Sophie Mayer and Charlotte Richard Andrews in The Guardian noted that despite the Hebrew meaning of Sarah's name being "princess", Sarah rejects her fantasy of being a princess in the scene when she bursts the bubble of her ballroom dream.[65] Identifying Sarah's abandonment of her princess fantasies, and refusal to be treated as one, as the central theme of Labyrinth, Tor.com's Bridget McGovern wrote that the film "systematically reject[s] the usual “princess” trope" through Sarah's refusal to find her "happy ending...on the arm of" King Jareth.[66] Critics note the contrast between Sarah's decision and that of the young heroines in traditional fairy tales, such as Cinderella, Snow White, Beauty and the Beast, and The Little Mermaid,[67][68][58] who choose marriage to a prince.[51] Also offered marriage and a kingdom and the chance to "go right from parents to husband, escaping a wicked stepmother by running to the arms of a wealthy suitor," Sarah instead chooses "herself. To loosen her grip on childhood...but not to rush into adulthood before she’s ready, like so many do," wrote L. S. Kilroy of online magazine Minerva.[58]

The character is also noted for her initiative and agency, as a rare example of a female lead who is the rescuer rather than the rescued.[69][70] Though as a girl who dreams of a fantasy world Sarah is often likened to Alice of Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz’s Dorothy Gale,[71][57] Gwynne Watkins of Yahoo! noted that Sarah differs from these characters as, unlike them, she does not "blithely stumble into her adventure."[72] Labyrinth's story is driven by Sarah's decisions, with her wishing Toby away before deciding to venture into the Labyrinth to retrieve him serving as the plot's primary catalyst.[73] Writing for The Black List Blog, Alissa Teige found that Sarah's dedication to rescuing her brother "defines her as a model for bravery, self-reliance and perseverance," and that the character's logical problem-solving methods in completing the Labyrinth "shows girls that they can defeat any obstacle, if they put their minds to it".[74] The character also actively resists temptation and distractions from her quest. Like Snow White, Sarah is poisoned by a gift of tainted fruit, causing her to forget her responsibilities and become carried away in a bubble of her own fantasy;[19] however, rather than wait to be rescued, Sarah breaks the enchantment herself by physically smashing the bubble.[73][68] She resists further escapist temptations in the form of her childhood comforts offered by the goblin junk-lady.[19] When Sarah is subjected to Jareth's erratic whims and elaborate obstacles, Kelcie Mattson of Bitch Flicks wrote, "she actively resists his narrative, twisting the conflicts around to suit her needs until Jareth becomes the one reacting to her."[73] Sarah's realisation of her own agency is one of the film's significant themes, culminated at the climax in her final remembrance and actualisation of the words, "You have no power over me".[57][73]

Sarah is identified as the Hero archetype in the Hero's journey monomyth.[45][67][57] A. C. Wise cited Labyrinth as an example of Maureen Murdock's female-centric Heroine's journey model, "an inward-facing journey that teaches the heroine about herself, a focus on family, and the importance of friendship."[75] Discerning Labyrinth as having Christian themes, Donna White in her contribution to the book The Antic Art: Enhancing Children's Literary Experiences Through Film and Video identified Sarah as a Christ figure because she is betrayed by Hoggle, "who is himself a Judas figure", and is continually tempted by a Satan-like Jareth. Sarah's final confrontation with Jareth takes place at the top of his castle, where he tempts her to give up her autonomy, similar to Satan's temptation of Christ on the mountain top.[76] Brian Froud said that Sarah's eating of the peach is symbolic of Eve's eating of the forbidden fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and "about [Sarah] entering into another phase of her life, a sensual phase ... to grow up and to have knowledge of other things."[16]

Reception

Critical response

Initial reception to the character from film critics was mixed.[77] Allen Malmquist of Cinefantastique deemed Sarah "a passable hero" but found that "her riddle-solving ability comes out of nowhere, and her moments of cleverness ... come too seldom to really make you respect and root for her."[78] Describing the character as "an attractively self-possessed child-woman on a purposeful journey", Michael Walsh of The Province wrote, "Sarah is a contemporary teen with a timeless appeal."[79] Paul Attanasio of The Washington Post felt that the film and character lacked a clear moral and that "all Sarah learns is some vague sense of her own independence".[80] Describing Sarah as "a curiously eccentric and seriously snooty teenager", Joe Baltake of The Philadelphia Inquirer felt that the film's lessons about "maturity, responsibility and the real world" are undermined by the final scene in which Sarah is reunited with her friends from the Labyrinth, "illustrating that Sarah is addicted to her make-believe world more than ever".[81] While acknowledging that Sarah matures over her adventure in the Labyrinth, Sheila Benson of the Los Angeles Times considered the character to be too unlikeable.[82] Rita Rose of The Indianapolis Star opined that because Sarah wishes away her brother, her attempt to get him back is "a heartless endeavor [that] makes it hard for us to care about her journey: Toby, after all, is better off with the jolly goblins than his nasty sister."[83] Francie Noyes of The Arizona Republic called Sarah "lovely" but felt that the film does not give enough focus to her character: "She is given little to do but push on bravely through yet another adventure. Jareth is more dynamic and the dwarf Hoggle is more endearing than Sarah is allowed to be."[84] Several reviewers considered Sarah to be overshadowed by the film's puppet characters and visual effects.[84][85]

Sarah has garnered a more positive reception in decades since Labyrinth's release. Heather Roche of the Times Colonist wrote that the character's "perseverance in solving the labyrinth is inspiring, and sends a great message to any viewers."[86] Some critics consider Sarah an unusually progressive character for a film made in the 1980s.[65][57][87] Zaki Hasan of Fandor wrote favourably of Sarah as "an intelligent young woman, neither portrayed in stereotypical terms nor baselessly sexualized," who "never loses her agency, even as sinister forces conspire to keep her from her goal."[88] Describing the character as a "hormonal hurricane...bratty and forthright but impossibly likeable", Josh Winning of Total Film wrote, "In-between her numerous rants of "It’s not fair!", Sarah's brash sensibilities mean she’s at least clever enough not to act intimidated by the Goblin King even if her insides are shuddering...Not only that, but she defeats her foe by using her brains, and doesn’t rely on Prince Charming to come to her rescue."[89] Sophie Mayer of The Guardian wrote, “Equally adept at using her lipstick as a cunning tool or fighting off goblin soldiers, Sarah was adept and affective, neither hyper-feminine nor forced into a masculinised version of heroism. She was selfish, bitter, headstrong, clever, and above all, wanted things to be fair. Not a princess but a proto-Notorious RBG Ruth Bader Ginsburg justice.”[65] Also in The Guardian, Charlotte Richard Andrews considered it "radical...to see a teenage girl not just slaying a lead fantasy role with her badassery, but battling a bona fide rock legend who takes her seriously, as both love interest and foe."[65] Writing for The Black List Blog, Alissa Teige considered Sarah to be an "essential cinematic heroine" and a strong role model for young women and girls.[74]

Jennifer Connelly's performance as Sarah initially polarized critics and received strong criticism from some reviewers.[90] Los Angeles Daily News critic Kirk Honeycutt referred to Connelly as "a bland and minimally talented young actress".[91] Noting the importance of the role, Nina Darnton of The New York Times found Connelly's portrayal of Sarah "disappointing...She looks right, but she lacks conviction and seems to be reading rehearsed lines that are recited without belief in her goal or real need to accomplish it".[56] Writing for The Miami News, Jon Marlowe opined, "Connelly is simply the wrong person for the right job. She has a squeaky voice that begins to grate on you; when she cries, you can see the onions in her eyes."[92] Contrary to these negative views, other critics praised her performance.[71][93] Hailing Connelly as "the most engaging heroine since Judy Garland tripped down the Yellow Brick Road and Elizabeth Taylor raced National Velvet to victory", Associated Press writer Bob Thomas wrote that she "has such a winning personality that she makes you believe in her plight and in the creatures she encounters".[94] Hal Lipper of the St. Petersburg Times similary enthused that "Connelly makes the entire experience seem real. She acts so naturally around the puppets that you begin to believe in their life-like qualities."[95]

Connelly's performance has garnered a more positive response in recent years. Brigdet McGovern of Tor.com wrote: "It’s a tribute to Jennifer Connelly’s performance that Sarah manages to exhibit all the hyper-dramatic martyrdom of your average 16-year-old while still seeming sympathetic and likeable — it’s easy to identify with her".[66] Glamour's Ella Alexander praised Connelly's portrayal of the protagonist as "empowering",[96] while Liz Cookman of The Guardian wrote, "She is confident and good-looking, yet not as overtly sexual as women are so often portrayed on-screen – a much stronger female role model than many available today."[53]

Legacy

Despite disappointing box office sales in the United States upon initial release, Labyrinth was later a success on home video, and has become a cult film.[97] According to Uproxx, Sarah's character arc is one of the main reasons why the film has developed a devoted fanbase: "Standing on the brink of growing up is one of the scariest times in everyone’s life, and art that can reflect that mix of fear and potential is cherished by many. For better or worse, viewers saw themselves in Sarah."[98] Bustle featured Sarah in its article "7 Feminist Childhood Movie Characters That Made You The Woman You Are Today", writing that the character is a strong role model for girls because "once she realizes that the world isn't fair and she's in charge of her own destiny, she can do anything."[99] SyFy Wire described the film as "one of the best depictions of female maturation and desire in pop culture of the '80s",[61] while The Arizona Republic characterised it as one of "8 of the best movies that celebrate girl power" due to Sarah's "determination and moxie" in solving the Labyrinth.[100]

Connelly's role as Sarah brought her international fame[101] and made her a teen icon.[102] The character has remained one of Connelly's best known performances.[103][104] In 1997, Connelly said, "I still get recognized for Labyrinth by little girls in the weirdest places. I can't believe they still recognize me from that movie. It's on TV all the time and I guess I pretty much look the same."[105] In 2008, Connelly said she found it amusing that many people continued to recognise her for Labyrinth 23 years after she worked on the film.[106]

Wonderwall.com named Sarah's white ballgown in the masquerade scene as one of "the most iconic dresses in movie history".[107] The costumes Connelly wore as the character are displayed at the Museum of the Moving Image's exhibition The Jim Henson Exhibition: Imagination Unlimited, which premiered at the Museum of Pop Culture in Seattle before opening at its permanent home in New York City in 2017.[108][109]

Other appearances

Sarah appears in Labyrinth's tie-in adaptations, which include the novelisation by A. C. H. Smith[2] and the three-issue comic book adaptation published by Marvel Comics,[110] which was first released in a single volume as Marvel Super Special #40 in 1986.[111] She also appears in the film's picture book adaptation,[112] photo album,[113] and read-along story book.[114][115]

Novelisation

Smith's novelisation of Labyrinth expands on Sarah's relationship with her absent mother, stage-actress Linda Williams, who had left Sarah and her father some years previously.[2] In the film, various photos of Linda and her co-star lover (portrayed by David Bowie) are briefly shown in Sarah's bedroom along with newspaper clippings reporting their “on-off romance”.[74][116] Sarah idolises both her mother and the boyfriend, named Jeremy in the novelisation; the book elaborates on Sarah aspiring to follow their example to become an actress and fantasising about living their celebrity lifestyle. After her adventure in the Labyrinth, having matured and re-evaluated her life, Sarah puts all of the clippings of Linda and Jeremy away as well as the music box that her mother had given her.[2]

"As The World Falls Down" music video

Sarah appears in the promotional music video for David Bowie's song "As The World Falls Down" from the Labyrinth soundtrack. Directed by Steve Barron in 1986,[117] the video features French actress Charlotte Valandrey[118] alongside footage of Jennifer Connelly taken from the film.

Return to Labyrinth

Sarah appears in Return to Labyrinth, a four-volume original English-language manga sequel to the film created by Jake T. Forbes and published by Tokyopop between 2006 and 2010. She is a supporting character in the series, which is set over a decade after the events of the film. After failing to get into the Juilliard School, Sarah has abandoned her ambitions to become an actress and lives a subdued life as an English teacher. She shares a close relationship with her brother Toby, who by this time is a teenager. Sarah is visited by Jareth, who has abdicated his throne and left the Labyrinth to Toby so that he could seek her out in the human world. Still in love with Sarah and desiring her as his queen, Jareth is disappointed to discover that she does not remember him and has discarded her fairy-tale fantasies for a more practical life. With the world of the Labyrinth in a deteriorating state and Jareth's powers weakening, he uses the last of his magic to jog Sarah's memories of him and the Labyrinth and attempts to entice her to create a new world with him from their shared dreams. However, Sarah wishes to preserve her friends from the Labyrinth, and realises her dreams by writing stories, allowing the existence of everyone in the Labyrinth to continue.[3]

Labyrinth: Coronation

Sarah appears in Labyrinth: Coronation, a 12-issue comic series written by Simon Spurrier and published by Archaia between 2018 and 2019. Her character and story arc is the same as that of the film, while the comic concurrently follows the parallel tale of Maria, another young woman who journeys through the Labyrinth to save a loved one, set several hundred years before Sarah. However, Maria ultimately fails to rescue her infant son, Jareth.[119] The Labyrinth that Sarah traverses is very different to Maria's, as in the series the Labyrinth becomes shaped to reflect and challenge each individual who attempts to solve it.[120]

Notes

- In Sarah's room, a scrapbook of newspaper clippings about a stage actress named Linda Williams is marked in handwriting as "mom" drawn with hearts.[1] The Labyrinth novelisation confirms Linda as Sarah's mother.[2]

- In the Return to Labyrinth series, Williams is Sarah's father's family name. Irene is Toby's mother, making Sarah and Toby half-siblings.[3]

- Sarah's father is unnamed in the film.[1] He is named Robert in the Labyrinth novelisation.[2]

- Sarah's stepmother is unnamed in the film.[1] She is named Irene in the Return to Labyrinth series.[3]

- Jim Henson: "What [Sarah] goes through is based on her own sense of fantasy. In her room, you see nearly all the elements of the maze foretold, in her toys and books. And her dolls represent the creatures she will meet."[10]

References

- Jim Henson (director) (1986). Labyrinth (film). TriStar Pictures.

- Smith (1986)

- Jake T. Forbes (w), Chris Lie, Kouyu Shurei (a). Return to Labyrinth v1-4, (2006-2010), Los Angeles, United States: Tokyopop

- "The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth Now Available on iTunes" (PDF) (Press release). New York, Los Angeles: The Jim Henson Company. New Video. 3 March 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

The film...follows Sarah Williams (Connelly) as she makes her way through the labyrinth...

- Jones, Alan (July 1986). Clarke, Frederick S. (ed.). "Labyrinth". Cinefantastique. Vol. 16 no. 3. pp. 7, 57.

- Edwards, Henry (28 June 1986). "Labyrinth: Jim Henson's new movie populated with more of his wonderful creatures". Daily Press. Newport News, Virginia. pp. D1–D2. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Pirani, Adam (August 1986). "Part Two: Into the Labyrinth with Jim Henson". Starlog. 10 (109): 44–48. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- Hawtin, Jane (30 June 1986). "Labyrinth film a Henson family affair". Star-Phoenix. Saskatoon, Canada. p. C4. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Block & Erdmann (2016), p. 27-29

- Elliott, David (26 June 1986). "Muppet-master's latest venture: 'Labyrinth'". Standard-Speaker. Hazleton, Pennsylvania. p. 37. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Magid, Ron (August 1986). "Goblin World Created for Labyrinth". American Cinematographer. Vol. 67 no. 8. pp. 71–74, 76–81.

- Sarah. in Block & Erdmann (2016), pp. 65-69

- Oleksinski, Johnny (26 April 2018). "Behind-the-scenes secrets from Bowie's cult classic 'Labyrinth'". New York Post. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Henson, Jim (29 January 1985). "1/29/1985 – 'Jennifer Connelly auditions for Labry. Cast within a week.'". Jim Henson's Red Book. Henson.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Henson, Jim (9 September 1984). "9/24/1984 "In San Francisco–meeting with George Lucas, Laura Phillips–Larry Mirkin and Mira V."". Jim Henson's Red Book. Henson.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Brian Froud (2007). "Audio Commentary by Conceptual Designer Brian Froud". Labyrinth (Anniversary Edition) (DVD). Sony Pictures Home Entertainment.

- "Labyrinth Production Notes". Astrolog.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 1999. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Labyrinth (Anniversary Edition) (DVD cover). Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. 2007.

...Frustrated by his crying, she secretly imagines the Goblins from her favorite book, LABYRINTH, carrying Toby away. When her fantasy comes true, a distraught Sarah must enter a maze of illusion to bring Toby back...

- Worley, Alec (2005). Empires of the Imagination: A Critical Survey of Fantasy Cinema from Georges Melies to The Lord of the Rings. McFarland & Company. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7864-2324-8.

- Birch, Gaye (8 December 2012). "Top 10 Movies Starring Toys That Come Alive". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Robberson, Joe (20 January 2016). "20 Things You Never Knew About 'Labyrinth'". Zimbio. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Wuntch, Philip (3 July 1986). "Muppet man hoping for hit with Labyrinth". The Ottawa Citizen. Dallas Morning News. p. D18. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- Thomas, Bob (3 July 1986). "New film from Jim Henson". The News. Paterson, New Jersey. Associated Press. p. 17. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cook, Bruce (17 July 1986). "Henson creatures create partnership with actors". The Central New Jersey Home News. Los Angeles Daily News. p. D6. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- The Jim Henson Company (2016) [Production notes first published 1986]. "Jennifer Connelly (Original 1986 Bio)". Labyrinth (30th Anniversary Edition) (Blu-ray booklet). Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. p. 12.

- Jennings, John (26 June 1986). "Henson creatures run amok in magical 'Labyrinth'". Tucson Calendar. Tucson Citizen. Tucson, Arizona. p. 5. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Sauter, Michael (June 1986). "Playing Hooky". Elle. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- O'Neill, Patrick Daniel (July 1986). "Jennifer Connelly: Growing Up in a World of Fantasy". Starlog. 10 (108): 81–84. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- Dickholtz, Daniel (1986). "Jennifer Connelly – I Love to Do Daring Things!". Teen Idols Mania!. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Des Saunders (director), Jim Henson (writer) (1986). Inside the Labyrinth (Televised Documentary). Los Angeles: Jim Henson Television.

- Lambe, Stacey (11 January 2016). "'Labyrinth' 30 Years Later: Jennifer Connelly Remembers David Bowie and 'Magical' Film Experience". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Dwyer, Michael (7 December 1986). "The puppeteer in his Labyrinth". Arts Tribune. The Sunday Tribune. Dublin, Ireland. p. 19. Retrieved 24 July 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- Henson, Jim (5 May 1985). "5/5/1985 – 'To Amsterdam – (Filming Labyrinth) – Forest – Wild Things, Shaft of Hands.'". Jim Henson's Red Book. Henson.com. Archived from the original on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- The Jim Henson Company (2016) [Production notes first published 1986]. "June 19—25 Ballroom". Labyrinth (30th Anniversary Edition) (Blu-ray booklet). Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. p. 26.

- Ballroom in a Bubble. in Block & Erdmann (2016), pp. 144-145

- DeNicolo, David (21 February 2014). "Jennifer Connelly: Her Style Timeline". Allure. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Francis, Deanna (29 June 1986). "Lucas-Bowie 'Labyrinth' is fun to follow". The South Bend Tribune. South Bend, Indiana. p. B5. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Webster, Garrick (March 2016). "The Golden Age of Fantasy Film Posters". ImagineFX. No. 132. Bath, UK: Future Publishing. pp. 41–47. ISSN 1748-930X. ProQuest 1789259631.

- Labyrinth (30th Anniversary Edition) (DVD/Blu-ray cover). Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. 2016.

A 16-year-old girl is given 13 hours to solve a dangerous and wonderful labyrinth and rescue her baby brother...

- Plath, James (26 September 2009). "Labyrinth – Blu-ray review". DVD Town. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Bitner, Brian (22 January 2016). "Why it Works: Labyrinth". JoBlo.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Edwards, Jack. "Dance Magic Dance – Labyrinth, A Retrospective". VultureHound. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Hubbard, Amy (27 June 2016). "The Romantic Rebel: Falling in Love with Jareth the Goblin King". OneRoomWithAView.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Eddy, Cheryl (29 August 2019). "8 Fantasy Films From The 1980s To Fuel Your Dark Crystal: Age Of Resistance Obsession". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Holste, Tom. (2012). Finding Your Way Through Labyrinth. In Carlen & Graham (2012), pp. 119-130

- Jinkins, Shirley (27 June 1986). "'Labyrinth' journey fun, but end result a letdown". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. p. B3. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Jordan, Rene (1 July 1986). "Un laberinto repleto de buen humor" [A labyrinth full of good humor]. El Miami Herald (in Spanish). p. 7. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cabin, Chris (27 June 2016). "'Labyrinth' 30 Years Later: Returning to Jim Henson & David Bowie's Fantasy World". Collider. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Kempley, Rita (27 June 1986). "Lost and Loving It, in 'Labyrinth'". The Washington Post. p. W29. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 138778737.

- Ellis, Jessica (12 January 2016). "I owe everything to David Bowie and 'Labyrinth'". HelloGiggles. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Balchin, Jean (21 May 2020). "'Labyrinth' stands the test of time". Otago Daily Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- George Lucas (2007). "Journey Through the Labyrinth: Kingdom of Characters". Labyrinth (Anniversary Edition) (DVD). Sony Pictures Home Entertainment.

- Cookman, Liz (12 August 2014). "Why I'd like to be … Jennifer Connelly in Labyrinth". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Bromley, Patrick (16 July 2016). "Class of 1986: The End of Childhood and the Legacy of LABYRINTH". Daily Dead. Daily Dead Media. Archived from the original on 17 July 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- McCabe, Taryn (27 June 2016). "The spellbinding legacy of Jim Henson's Labyrinth". Little White Lies. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- Darnton, Nina (27 June 1986). "Screen: Jim Henson's 'Labyrinth'". The New York Times.

- Webb, Katherine (12 June 2017). "The Babe With the Power". Bright Wall/Dark Room. No. 48: The Hero's Journey. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- Kilroy, L. S. (16 October 2015). "Labyrinth: More Than Just David Bowie in Tight Pants". Minerva Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- "Labyrinth". An Sionnach Fionn [The White Fox]. 14 May 2011. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Shiloh, Carroll (2009). "The Heart of the Labyrinth: Reading Jim Henson's Labyrinth as a Modern Dream Vision". Mythlore. Mythopoeic Society. 28 (1): 103–112. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Donaldson, Kayleigh (30 May 2020). "If We Must Have A Labyrinth Sequel, Here's What We Want From It". SyFy Wire. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Gracey, James (2017). The Company of Wolves. Devil's Advocates. Leighton Buzzard, United Kingdom: Auteur Publishing. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-911325-31-4.

- Perry, Anne (11 January 2016). "Labyrinth: An Appreciation". Hodderscape. Archived from the original on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Watkins, Gwynne (12 January 2016). "The Magic of the Goblin King: An Apprecation for David Bowie in 'Labyrinth'". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Andrews, Charlotte Richardson (12 January 2016). "How Labyrinth led me to David Bowie". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- McGovern, Bridget (8 January 2014). "Suburban Fantasy, Gender Politics, Plus a Goblin Prom: Why Labyrinth is a Classic". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Monique (2 May 2014). "Labyrinth (1986): Power, Sex, and Coming of Age". The Artifice. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Griffin, Sarah Maria (14 January 2016). "He Moves The Stars For No One – David Bowie in Labyrinth". Scannain. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Prokop, Rachael (25 January 2012). "Literally the Best Thing Ever: Labyrinth". Rookie. No. 5. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- Rose, Sundi (11 September 2016). "Jim Henson's son just explained why we never got a "Labyrinth" sequel". HelloGiggles. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- Hurlburt, Roger (27 June 1986). "When A Wish Makes You Wish You Hadn't". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Watkins, Gwynne (12 January 2016). "The Magic of the Goblin King: An Apprecation for David Bowie in 'Labyrinth'". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Mattson, Kelcie (28 June 2016). ""You Have No Power Over Me": Female Agency and Empowerment in 'Labyrinth'". Bitch Flicks. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Teige, Alissa; Hagen, Kate (22 March 2017). "Essential Cinematic Heroines: Alissa Teige on Sarah Williams". The Black List Blog. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Wise, A. C. (2016). "Into The Labyrinth: The Heroine's Journey". In Valentinelli, Monica; Gates, Jaym (eds.). Upside Down: Inverted Tropes in Storytelling. Apex Book Company. pp. 294–304. ISBN 978-1-937009-46-5.

- White, Donna R. (1993). "Labyrinth: Jim Henson's 'Game' of Children's Literature and Film". In Rollin, Lucy (ed.). The Antic Art: Enhancing Children's Literary Experiences Through Film and Video. Highsmith Press. pp. 117–129. ISBN 978-0-917846-27-4.

- Byrnes, Paul (11 December 1986). "Babysitting with goblins". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 16. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Malmquist, Allen (January 1987). Clarke, Frederick S. (ed.). "Henson's fantasy sapped by its lack of theme or emotion". Cinefantastique. Vol. 17 no. 1. pp. 42, 59.

- Walsh, Michael (4 July 1986). "One of the best". The Province. Vancouver, Canada. p. 47. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Attanasio, Paul (27 June 1986). "'Labyrinth': Lost in a Maze". The Washington Post. p. D11. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 138816272.

- Baltake, Joe (30 June 1986). "'Labyrinth': An Unpleasant Trip". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Benson, Sheila (26 June 1986). "MOVIE REVIEW: GOING TO GREAT LENGTHS IN A TRYING 'LABYRINTH'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Rose, Rita (2 July 1986). "Labyrinth". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. p. 35. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Noyes, Francie (2 July 1986). "Francie Noyes on movies: Singles, goblins, gymnasts". City Life. The Arizona Republic. 3 (40). pp. 24, 31. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

-

- Garrett, Robert (27 June 1986). "'Labyrinth' a gift from Jim Henson". The Boston Globe. pp. 31, 34. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Filmeter: Labyrinth". Sunday News. Lancaster, Pennsylvania. 6 July 1986. p. F4. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Duncan, Helen (December 1986). "Cosmo reviews movies". Cosmopolitan.

- Roche, Heather (1 February 1999). "Henson's art shines through". Times Colonist. p. D2. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Mayer, So (2015). Political Animals: The New Feminist Cinema. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-85772-797-8.

- Hasan, Zaki (10 September 2016). "Thirty Years in a LABYRINTH". Fandor. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Winning, Josh (13 May 2010). "Why We Love... Labyrinth". Total Film. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Craft, Dan (12 July 1986). "Trapped in an endless maze of special effects". The Pantagraph. Bloomington, Illinois. pp. 4, 19. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

Connelly emerges an utterly charmless and enempathetic heroine. Her matter-of-fact reactions to the fantastical situations, monotone vocal delivery and inexpressive face render her character a nonentity throughout.

- Honeycutt, Kirk (27 June 1986). "Quality gets lost in Labyrinth". Weekend. The Spokesman-Review. Los Angeles Daily News. p. 12. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Marlowe, Jon (27 June 1986). "Bowie's trapped in Labyrinth". The Miami News. p. 2C. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

-

- Eckberg, Lucy Choate (19 October 1986). "'Labyrinth': Fairy tale with muppet magic". Winona Daily News. p. 23. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

It is Jennifer Connelly who steals the show in her portrayal of Sarah...

- Johnson, Malcolm L. (26 June 1986). "'Labyrinth' Imaginative, but Loses Its Way". Hartford Courant. Hartford, Connecticut. p. 24. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

Sarah, engagingly played by pretty, fresh and feisty Jennifer Connelly...

- Rambeau, Catherine (27 June 1986). "'Labyrinth' twists into a fantasy too scary for youngsters". Detroit Free Press. p. 8C. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

Connelly is charming and beautiful, at first deliberately over-dramatic, as Sarah would likely be at that age.

- Eckberg, Lucy Choate (19 October 1986). "'Labyrinth': Fairy tale with muppet magic". Winona Daily News. p. 23. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Thomas, Bob (3 July 1986). "Henson, Lucas offer something different". Hattiesburg American. Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Associated Press. p. 6B. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Lipper, Hal (27 June 1986). "Fantastic puppets can't escape fairy tale maze". St. Petersburg Times. p. 1D, 4D. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Alexander, Ella (20 June 2016). "Labyrinth turns 30: 16 reasons it's the best film ever". Glamour. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- Block & Erdmann (2016), p. 180

- Fikse, Alyssa (20 September 2016). "How David Bowie, Practical Magic, And An Army Of Fans Turned 'Labyrinth' Into A Transcendent Cult Film". Uproxx. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Garis, Mary Grace (19 August 2015). "7 Feminist Childhood Movie Characters That Made You The Woman You Are Today". Bustle. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Vandenburgh, Barbara (25 August 2017). "8 of the best movies that celebrate girl power". Arizona Republic. Phoenix, Arizona. p. D2. Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cameron, Marc (22 July 2005). "Film: The fearful star; Jennifer Connelly admits to being insecure and dreading that she is a 'thicky'. She explains her paranoia to MARC CAMERON". The Independent. London. ISSN 0951-9467. ProQuest 310793651 Gale A134282749

- Barlow, Helen (6 February 2009). "Ladies in waiting". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 4. ISSN 0312-6315. ProQuest 364560479.

Connelly ... achieved iconic status among teenagers alongside David Bowie in 1986's Labyrinth

- McCarthy, Ellen (12 December 2008). "Jennifer Connelly Doesn't Stand Still". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. p. W28. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 410281654.

Connelly ... became a teen star in David Bowie's cult classic "Labyrinth.

- Daly, Susan (8 November 2011). "Fame Evader". Irish Independent. Dublin. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 24 July 2020 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- McCarthy, Ellen (12 December 2008). "Jennifer Connelly Doesn't Stand Still". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. p. W28. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 410281654.

- Power, Ed (27 May 2020). "Michael Jackson, Monty Python and Bowie's trousers: the chaotic making of Labyrinth". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Sykes, Pandora (3 April 2016). "Jennifer Connelly: 'I never wanted to be the damsel in distress, I wanted to be the badass'". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- Spelling, Ian (September 1997). "Damsel in the Dark". Starlog (242): 50–51. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Standing Still for Jennifer". Wales on Sunday. Cardiff, Wales. 7 December 2008. p. 2. ISSN 0961-1002. ProQuest 341980887 Gale A190185705

- Salazar, Bryanne (2 May 2019). "Most Iconic Dresses in Movie History". Wonderwall.com. Whalerock Industries. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Arnold, Sharon (29 May 2017). "Jim Henson was more than a puppetmaster". Crosscut.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Hoffman, Jordan (20 July 2017). "Psychedelia, clubbing and Muppets: inside the world of Jim Henson". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- Labyrinth (Marvel, 1986 Series) at the Grand Comics Database

- Marvel Super Special #40 at the Grand Comics Database

- Gikow, Louise; McNally, Bruce (1986). Labyrinth: The Storybook Based on the Movie. New York: Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 978-0-03-007324-3.

- Grand, Rebecca; Brown, John (1986). Labyrinth: The Photo Album. New York: Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 978-0-03-007323-6.

- Labyrinth Read Along Adventure on Discogs

- Read Along Adventure: Labyrinth at Google Arts & Culture

- Wurst II, Barry (24 April 2018). "LABYRINTH Old Movie Review". Maui Time. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Pegg (2016), p. 27

- Andrian, Andy (16 November 2018). "Son parcours, sa maladie... Les secrets de Charlotte Valandrey" [Her journey, her illness ... The secrets of Charlotte Valandrey]. Linternaute.com (in French). CCM Benchmark Group. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Prange, Melissa (27 March 2019). "Jim Henson's Labyrinth: Coronation #11-#12 Review". Rogues Portal. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Pleasant, Robbie (24 August 2018). ""Labyrinth Coronation" #6". Multiversity Comics. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Bibliography

- Block, Paula M.; Erdmann, Terry J. (2016). Labyrinth: The Ultimate Visual History. London, United Kingdom: Titan Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78565-435-0.

- Carlen, Jennifer C.; Graham, Anissa M., eds. (2012). The Wider Worlds of Jim Henson: Essays on His Work and Legacy Beyond The Muppet Show and Sesame Street. Jefferson, NC, United States: McFarland & Co Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-6986-4.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (7th ed.). London, United Kingdom: Titan Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Smith, A.C.H. (1986). Labyrinth: A Novel Based on the Jim Henson Film. New York, United States: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-03-007322-9.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sarah Williams |