Shipbuilding in the American colonies

Shipbuilding in the American colonies was the development of the shipbuilding in North America (modern Canada and the United States), from the beginning and end to of British colonization to American independence.

Trade with other countries

In the colonial period European powers were the economic power houses of the world. They heavily influenced commerce and trade in both North and South America. In particular, the British and the Spanish exerted their influence over the colonial economies. This influence helped determine the direction of economic advancement on the American continents. In Europe, there was an influx in the demand for products that required tropical climates. For example, tobacco and sugarcane were major items of trading.[1] The climate in the two American continents was conducive to the growth of these products, hence the increased European interest in that part of the world in the period. The increased demand resulted in increased efforts of production and consequently an influx in investment.[1]

.jpg.webp)

Some areas in the colonies were not conducive to the development of agriculture. This was the case in the New England colonies which consisted of the present day New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, Maine and Massachusetts. These areas have poorly developed soils and are susceptible to poor climatic conditions. Nevertheless, New England did have prime access to the Atlantic Ocean. New England was able to create a thriving fishing industry to increase their shipbuilding market. New England’s ideal placement and the demand that existed for water transport implied that they were involved in the shipping industry as a function of their agricultural impotence, their locations and the development of a fishing industry.[2]

Transatlantic triangular trade

The transatlantic triangular trade involved three journeys each with the promise of a large profit and a full cargo. In reality, the journey was more complicated with ships traveling from all over Europe carrying manufactured goods to different ports along the African coast to trade for slaves. The ships from Africa then sailed across the Atlantic to the Caribbean and Americas to trade the slaves for raw materials. Finally the ships from America returned to Europe with raw materials such as sugar, tobacco, rice and cotton. The system of Triangular Trade allowed for goods to be traded for other goods, rather than being bought or sold.

Ships from England would go to Africa carrying iron products, cloth, trinkets and beads, guns and ammunition. The ships traded these goods for slaves, gold and spices (pepper). Ships from Africa would go to the American Colonies via the route known as the 'Middle Passage'. The slaves were exchanged for goods from the Americas, destined for the slave plantations. Ships from the Americas would then take raw materials back to England. The British would use the raw materials to make 'finished goods'.[3]

Source materials and methods

The east coast of the United States provided a specifically dense area for raw materials especially around Massachusetts. There was an abundance of oak forests that provided wood for the ships.[4] In the late 1680s “there were more than 2 dozen sawmills around the Maine and Massachusetts areas. These sawmills, along with a dense supply of wood, helped to increase the business of colonial shipbuilding. The wood was usually white oak, but “cedars, chestnuts, and black oaks were perfect for the underwater portion of the ships.”[5] Demand was high for wood, colonial Americans needed faster ways of producing more wood. This led to inventions of different types of sawmills. One of the first types of sawmills was the water sawmill. This process allowed for faster, more efficient wood to be made for shipbuilding.

Wood process

The shipbuilding process began with the frame and then heating the hull of the ship. This was done using steamers and wood as fuel. Planks were heated up to be able to bend with the curve of the ship.[6] Once all the framing and planking was completed, caulking waterproofed the ship. Ships made of wood required a flexible material, insoluble in water, to seal the spaces between planks. Pine pitch was often mixed with fibers like hemp to caulk spaces which might otherwise leak. Crude gum or oleoresin could be collected from the wounds of living pine trees.

Tools

Tools used included the mallets and irons. Mallets were usually 16 inches from end to end with the handle bar usually being about 16 inches. The material that was hammered in between each of the planks was typically oakum, a kind of hemp fiber. There were oftentimes 2-3 layers of this oakum fiber placed in between the planks. Putty would be put on afterwards to finish off the waterproofing. Tar, which also came from the thousands of trees available, was oftentimes spread over the top of these planks and they were covered with copper plating. Copper was used because without it the ship’s hull would often get infected with worms. The copper was fastened to the ship with bronze nails. The ships were oftentimes painted yellow, to help make the ship appear faster and newer.

Uses of ships

The early wooden vessels worked for business angling and remote exchange likewise offered ascend to an assortment of subordinate exchanges and commercial enterprises in the zone, including sail making, chandleries, rope strolls and marine railroads. Shipyards in Essex and Suffolk regions are credited with the development of the conventional American dory and constructed those that included the prestigious Gloucester, Massachusetts angling armada, freed the settlements from British guideline, reinforced the vendor and maritime armadas that made the United States a force to be reckoned with and assumed essential parts in World War I and World War II. Numerous vessels incorporated into this schedule were either developed in Massachusetts or are illustrative of the sorts of vessels manufactured and repaired in Massachusetts shipyards.[7]

Economic impact

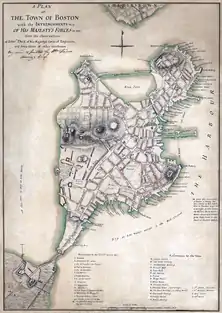

In the American colonies shipbuilding had an immense impact on the economy. The colonies had a comparative advantage in shipbuilding with their vast natural resources, skilled craftsmen and capital infused from the British empire. The colonies' ability to build ships with their large timber stock flooded the economy with capital from Britain it had not previously seen. Boston, Massachusetts became the central point for the boom of shipbuilding because it was the main distribution point for most of the shipping tonnage.[8] The shipbuilding industry needed plenty of skilled labor to support it and with America's large forest industry many craftsmen already had skills working with wood. These skills transitioned to the shipbuilding industry.

Impact of wealthy Boston merchants

The introduction of British credit and complicated account balancing during King William's War, in the 1690s, changed how Boston merchants financed the shipbuilding industry. As British credit flowed into the community, Boston merchants began creating long-term credit arrangements with waterfront tradesmen and other skilled laborers. Local labor and exchanges of goods could be sustained across scores of people linked with myriad small amounts of credit and debit without cash. But the shipbuilding industry generated the labor and capital necessary for merchants to create larger and more intricate financial networks that solidified their position of power within both the local and the Atlantic economy. The extension of credit to a large portion of society helped spur the shipbuilding boom period from 1700-1717. Merchants such as Elias Hasket Derby, ordered schooners and brigs from the North River (Massachusetts Bay) shipyards and in which led him to trading with China. This made Derby one of America's first millionaires.

In 1717, Boston learned that disaster had struck in the West Indies. The Spanish attacked and destroyed the British settlement at Trist in the Bay of Campeche, where Boston merchants had long extracted log wood for sale in England and Europe. Boston's economy was sent into a tailspin. Ship orders decreased and confidence in long-term credit arrangements plummeted triggering an unprecedented amount of lawsuits. Boston's economic catastrophe in 1717 led to the creation of new currency and credit laws that directly affected how merchants and tradesmen in the shipbuilding industry conducted business.[9] This meant more stringent lending practices to trustworthy tradesmen and a stronger, more transparent industry that continued to dominate the Atlantic economy.

Skilled labor

Much of the skills required of shipwrights or shipbuilders were obtained through on-the-job-training. Many of the earliest shipyards and boat shops operated as family businesses passed down from generation to generation.[4] The town of Essex, Massachusetts became the center for skilled craftsmen and produced the best boats. In 1794, Tenche Coxe described America's shipbuilding experiences as an art for which the United States is peculiarly qualified by their skill in construction and vast natural resources.[10] Skilled shipbuilding craftsmen were always in demand during the colonial period because shipbuilding pertained to many areas of the economy. The uses of ships in trade, fishing and travel meant there was a continual supply and demand for shipbuilding skills.

Natural resources

Until the mid-nineteenth century, forests were the basis of sea power in all its military and commercial aspects, and each nation strove to maintain its independence by protecting timber supply routes that often extended over great distances. This drove the British to encourage shipbuilding in the American colonies. Over 1,000 vessels were launched out of the American colonies during the seventeenth century. Boston, Massachusetts was the distribution hub of natural resources that included cedar, maple, white pine, spruce and oak timber cut in New England. By the mid seventeenth century shipwrights were beginning to take advantage of oak, mulberry, cedar and laurel in Delaware, Maryland and Virginia. During the seventeenth century iron became increasingly used by shipwrights for bracing, bolts, anchors and ordinance. The American colonies were able to meet their demand for iron by utilizing their expansive charcoal reserves.[8] These vast natural resources made American colonial ships cost 25 Mexican dollars per ton versus English ships' 69 Mexican dollars per ton according to a 1794 account by Tenche Coxe.[10]

Demand

The shipbuilding industry was extremely important, especially to the New England Colonies in Colonial Times. The first ships were built for fishing, but trade was also conducted by water, which eventually led to the real demand in shipbuilding. Shipyards rose up all along the coast of New England. The abundance of timber and lumber made shipbuilding cheap in the colonies. Many different types of work were related to the shipbuilding industry including carpenters, joiners, sail makers, barrel makers, painters, caulkers and blacksmiths. There were 125 colonial shipyards by the year 1750.

Shipbuilding was a particularly successful and profitable industry in Massachusetts, with its miles of coastline featuring protected harbors and bays. Mass quantities of lumber and other raw materials were found in abundance. The early wooden vessels built for commercial fishing and foreign trade also gave rise to a variety of supporting industries in the area, including sail making, chancelleries, rope walks and marine railways. Due to the booming shipbuilding industry some colonies such as Maryland experienced deforestation and in turn a depleted stock of available timber.

Beginning in roughly 1760, it became necessary for Maryland to import timber from other colonies. However, in New England the shipbuilding industry continued to boom. In fact, in New England the abundance of good timber enabled colonists to produce ships thirty percent cheaper than the English, making it the most profitable manufactured export during the colonial period.[11]

Even with the forests closest to New York and Boston depleted, the country still had vast timber reserves, making the cost of construction much lower."[12] An American vessel made of more expensive live oak and cedar would cost thirty-six dollars to thirty-eight dollars per ton, while a similar vessel made of oak in England, France, or Holland would cost fifty-five dollars to sixty dollars per ton.[12]

Key drivers

One of the main drivers of demand Naval architecture changed gradually in the eighteenth century. Of five classes of seventeenth-century vessels, only ship continued to be built after the early 1700s. The others were replaced by four new types: sloop, schooner, brigantine, and snow. Given the constant emigration of shipwrights from England and the limited advances in technology, it is not surprising that eighteenth-century Americans were usually familiar with trends abroad. Sloop and schooner were more manageable and could operate with fewer men. Smaller sails meant lighter masts and rigging, which in turn reduced expenses for the owners.[13]

In addition, availability alone fails to explain the general popularity of New England-built tonnage in other colonies. Cost may have been the decisive factor. After all, among the American colonies, New England shipyards produced the most tonnage and often had the lowest building rates. Convenience must have been an important attraction also. Surplus goods and ships could be exchanged for mutual benefit[14]

The sale of colonial ships built on the British market enabled English merchants to secure cheap tonnage and gave American merchants an important source of income to pay for their imports. All the colonies exported shipping, but once again, New England was the chief contributor.

_(14782832555).jpg.webp)

New England supplied about half of the tonnage in Great Britain at the end of the colonial period. Within New England, Massachusetts and New Hampshire were the leading producers; Pennsylvania; followed by Virginia and Maryland, launched most of the remaining tonnage. British demand for American natural resources provided a foreign market for colonial shipbuilding.[15]

References

- Bruchey, S. (2013). Roots of American Economic Growth 1607-1861 an Essay on Social Causation. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

- Inikori, J. (2009). The Atlantic slave trade: Effects on economies, societies, and peoples in Africa, the Americas, and Europe. Durham: Duke University Press

- "Triangular Trade ***".

- http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/maritime/ships.html

- These saw mills, along with the dense supply of wood, helped to increase the business of colonial shipping. The wood was usually white oak, but “Cedars, chestnuts, and black oaks were perfect for the underwater portion of the ships.”

- "Tea Party Ships Reconstruction - Boston Museum Videos".

- "Ships & Shipbuilding". Maritime History of Massachusetts. National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places and Maritime Heritage Program. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Carroll, Charles (October 1981). "Wooden Ships and American Forests". Journal of Forest History. 25 (4): 213–215. doi:10.2307/4004612. JSTOR 4004612.

- "Building and Outfitting Ships in Colonial Boston". web.b.ebscohost.com. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- "American Eras: Shipbuilding". Encyclopedia.com. 1997. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- (1) Rutkow, E. (2012). American Canopy: Trees, Forests, and the Making of a Nation. New York: Scribner.

- "Shipbuilding Facts, information, pictures - Encyclopedia.com articles about Shipbuilding".

- Goldenberg, Joseph (1976). Shipbuilding in Colonial America. The United States of America: University Press of Virginia. pp. 77–78. ISBN 0-8139-0588-5.

- Goldenberg, Joseph (1976). Shipbuilding in Colonial America. United States of America: University Press of Virginia. pp. 97. ISBN 0-8139-0588-5.

- Goldenberg, Joseph (1976). Shipbuilding in Colonial America. United States of America: University Press of Virginia. pp. 99. ISBN 0-8139-0588-5.