Sichuan Basin

The Sichuan Basin (Chinese: 四川盆地; pinyin: Sìchuān Péndì), formerly transliterated as the Szechwan Basin, sometimes called the Red Basin, is a lowland region in southwestern China. It is surrounded by mountains on all sides and is drained by the upper Yangtze River and its tributaries. The basin is anchored by Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province, in the west, and the direct-administered municipality of Chongqing in the east. Due to its relative flatness and fertile soils, it is able to support a population of more than 100 million. In addition to being a dominant geographical feature of the region, the Sichuan Basin also constitutes a cultural sphere that is distinguished by its own unique customs, cuisine and dialects. It is famous for its rice cultivation and is often considered the breadbasket of China. In the 21st century its industrial base is expanding with growth in the high-tech, aerospace, and petroleum industries.

| Sichuan Basin | |

|---|---|

| Red Basin | |

Sichuan Basin landscape in Zitong County | |

Map of China with Sichuan Basin highlighted | |

| Length | 500 km (310 mi) |

| Width | 400 km (250 mi) |

| Area | 229,500 km2 (88,600 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

| Country | China |

| Provinces | Sichuan, Chongqing |

| Region | Southwest China |

| Coordinates | 30°30′N 105°30′E |

Geography

The Sichuan Basin is an expansive 229,500 km2 (88,600 sq mi) lowland region in China that is surrounded by upland regions and mountains.[1] Much of the basin is covered in hilly terrain. The basin covers the eastern third of Sichuan Province and the western half of Chongqing Municipality.

The westernmost section of the Sichuan Basin is the Chengdu Plain, occupied by Chengdu, provincial capital of Sichuan. The Chengdu Plain is largely alluvial, formed by the Min River and other rivers fanning out when entering the basin from the northwest. This flat region is separated from the rest of the basin by the Longquan Mountains. The central portions of the Sichuan Basin are generally rolling, covered by low hills, eroded remnants of the uplifted Sichuan Basin floor. In some parts of the extreme northern Basin and in Weiyuan County in the southwest, there are ancient dome-shaped low mountains in their own right.[2]

The easternmost part of the Sichuan Basin consists of significant fold-and-valley terrain, resulting in long vegetated ridges rising above the lowlands. Major ridges of this type include Huaying Mountain, Mingyue Mountain, and Fangdou Mountain.[3] The urban centre of Chongqing lies within this region.

To the west and northwest, the Sichuan Basin abuts the eastern edge of the Tibet Plateau. Major mountain ranges along this edge include the Daxue Mountains, the Qionglai Mountains, the Min Mountains, and the Longmen Mountains.[4] The Sichuan Basin is separated from the Indian subcontinent to the southwest by the massive Hengduan Mountains, an extension of the Tibetan Plateau. Here, Mount Emei is a significant peak that rises abruptly from the basin floor.

On the south and southeast, the Sichuan Basin is flanked by the Yungui Plateau. Mountain ranges here include the Wulian Feng and Dalou Mountains. Lastly, the Sichuan Basin is separated from the traditional heartland of China to the east and northeast by the Wu Mountains and Daba Mountains. The Daba, a southern subrange of the Qin Mountains, has long been a barrier to travel between the Sichuan Basin and the rest of China.[5]

The entirety of the Sichuan Basin is drained by the Yangtze River and its tributaries.[4] The main stem of the Yangtze, the Jinsha River, enters the basin in the south at Yibin where it meets the Min River, which enters the basin from the northwest at Dujiangyan City and flows southerly to meet the Jinsha at Yibin where together they form the Yangtze in name. The Dadu River enters from the west and joins the Min at Leshan. The Jialing River enters from the north and flows across the entire width of the Sichuan Basin to meet the Yangzte at Chongqing. Northeast of Chongqing, the Yangtze cuts an outlet through the mountains at the eastern edge of the basin known as the Three Gorges. Other significant rivers almost wholly within the Sichuan Basin include the Tuo River, the Fu River, and the Qu River.[3]

Climate

Due to the surrounding mountains, the Sichuan Basin often experiences fog and smog as a result of temperature inversion caused by the basin's convective layer being capped by a layer of air moving east across the Tibet Plateau.[1][6] A moist, often overcast, four-season climate dominates the basin, with cool to mild winters occasionally experiencing frost, and hot, very humid summers. The intensity of summer varies rather widely throughout the basin, depending on location. Generally, the climate is warmer and wetter in the eastern parts of the Sichuan Basin.[4] The basin's climate is classified as humid subtropical under Koppen classification.

Geology

The Sichuan Basin forms the rigid northwest edge of the Yangtze tectonic plate. The Yangtze Plate's complex relationship with the surrounding Eurasian Plate is evidenced at its margins.[7] Orogeny formed by the Indian Plate's collision with Eurasia has compressed against the Sichuan Basin's western edge, most notably along the Longmenshan Fault, the epicenter of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake. The basin's rigidity withstands much of the Tibetan Plateau's eastern movement, but dramatic folds have formed within the Yangtze Plate along the Sichuan Basin's eastern edges. Here, ancient faults interact with the Daba Mountains, themselves a result of pressure between the Yangtze and Eurasian Plates in a perpendicular direction.[8]

Until 6 million years ago, a large lake filled the Sichuan Basin.[4] The basin's soils today are largely exposed red sandstone,[1] leading to the "Red Basin" nickname for the region. The Sichuan Basin's well preserved Jurassic layers have proven valuable to paleontology, such of those of the Shaximiao Formation, near Zigong, which preserves abundant remains of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals.[9]

Biodiversity

.jpg.webp)

Originally, the Sichuan Basin was covered by the Sichuan Basin evergreen broadleaf forests. With human settlement, agriculture has taken root across most of the fertile basin and reduced the original forest to small patches on hills and mountains including Mount Emei.[10] The extensive ridges in the eastern Sichuan Basin preserve elements of the original forests.[3] A greater variety of natural landscapes and wildlife have been at least partially preserved in the mountains surrounding the basin where human settlement has been less intensive. The natural ecosystems of these mountains have been classified by the World Wildlife Fund as the Qionglai-Minshan conifer forests to northwest and the Daba Mountains evergreen forests to the northeast and east.[11][12]

Previously only known in fossils and thought to be extinct, the Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) was rediscovered in 1943 in the hilly Lichuan County, on the eastern mountain fringe of the Sichuan Basin.[13] The Dawn Redwood is distinctive because it is a deciduous conifer.

Human development

History

Relative to the areas surrounding the upper Yellow River and the North China Plain, the Sichuan Basin has played a peripheral role in the development of Chinese civilization. Due to the fertile agricultural characteristics of the basin, numerous cultures developed prior to integration with Chinese society.[3] No written records exist from early cultures in the Sichuan Basin. What little is known about the area is from when contact was made with Chinese civilization and from the archaeological site of Sanxingdui.[14] Predominant among the known ancient cultures was the Shu State that was independent from Chinese civilization until it was strategically conquered by the Qin in 316 BCE during the Warring States Period.[15] The Sichuan Basin was integrated into Imperial China under Qin Dynasty for whom it was an important agricultural resource.[14]

During the period of the Three Kingdoms, the Sichuan Basin was at the centre of another independent Shu State, until it was reunified with China in the 3rd century CE by the Jin dynasty.[15] Around this time the basin's population is estimated to have been 1 million, with Chengdu the leading city. After the collapse of the Tang Dynasty in 907, the Sichuan Basin became home to a third Shu state, this time lasting only two decades.[15] During successive Chinese dynasties, the Sichuan Basin was firmly integrated with Greater China. Mass migration occurred during the Ming Dynasty as the basin became one of the primary rice-producing regions of China. The basin's population fell sharply in the 17th century due to devastation caused by famine, war, and possible genocide.[16] After this time, the basin was repopulated with emigrants from China, further assimilating the unique cultures and peoples inhabiting the basin.[17] During the Second Sino-Japanese War when much of Eastern China was occupied by Japanese forces, Chongqing in the Sichuan Basin served as the Republic of China's capital.[15]

Demographics and economy

Owing to its vast fertile plains, the Sichuan Basin has long supported a high concentration of human population.[1] The major population centres of Chengdu and Chongqing have flourished with their hinterlands providing staples such as rice, wheat, and barley. Irrigation in the western part of the basin has been controlled for over two millennia by the monumental Dujiangyan irrigation system, where the Min River enters.[18] The region has been known as a major breadbasket of China, especially in the 20th century during times of war.[3] Sichuan Basin also became a major focus of industrial development during Mao's Great Leap Forward. In more recent times, the Sichuan Basin and the corridor between Chengdu and Chongqing have become developed as an economic centre known as the Chengyu Area. This area is mostly coterminous with the basin; it is part of a branding scheme by the Chinese government to attract investment to the area. Chemical, textile, electronic, aerospace, and food industries have all been developed as part of the Chengyu Area.[3] Another emerging industry in the basin is the petroleum industry, currently exploring and extracting from oil reserves locked under the eastern parts of the basin.[19]

While population growth stagnated during the Great Leap Forward, it has since recovered. Today, the basin has a population of approximately 100 million.[3] Administratively, the entire basin was part of Sichuan province until Chongqing was separated into a provincial-level municipality in 1997. In addition to Chengdu and Chongqing, significant cities found within the Sichuan Basin include Guangyuan, Mianyang, Deyang, Nanchong, Guang'an, Dazhou, Ya'an, Meishan, Leshan, Ziyang, Suining, Neijiang, Zigong, Yibin, and Luzhou. The former cities of Fuling and Wanzhou are now considered districts within Chongqing, but maintain their status as separate urban centres along the Yangtze.[20]

Culture

_(2269517013).jpg.webp)

Despite Sichuan Basin's gradual integration with Chinese society, some unique elements of Sichuanese culture remain. Sichuanese cuisine today is renowned for its unique flavours and levels of spiciness.[18] The Sichuanese branch of Mandarin Chinese is barely mutually intelligible with Standard Mandarin and originated in the Sichuan Basin. Today, Sichuanese is spoken throughout eastern Sichuan province, Chongqing, southern Shaanxi, and western Hubei.

Transportation

While transportation across the Sichuan Basin has been facilitated by relative flatness, access to and from the basin has long been a challenge.[3] Chinese poet Li Bai once claimed that the road to Sichuan was "harder than the road to heaven".[21] Until the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, the Yangtze River was the primary transportation corridor. Connecting the basin with the Yellow River valley to the north, the 4th century BCE Shu Roads were an engineering feat for their time.[5] Most famously, the semi-legendary Stone Cattle Road is said to have been utilized by the Qin to first conquer the Sichuan Basin in 316 BC.[15]

Transportation to the west from Sichuan has proven to be an even greater challenge, with steep mountains and deep valleys hindering movement. Nevertheless, the Sichuan Basin has played a role as a stopover on the southern Silk Road and provided the most direct route between India and China. The southern trade route to Tibet also passed through the basin, eventually crossing Kham and the Derge Kingdom to the west.[22] The Long March passed to the west of Sichuan Basin in 1935 with great difficulty.[15]

In the 20th century, the Sichuan Basin was connected to the rest of China by railways. The Chengyu Railway, completed in 1952, connected Chengdu and Chongqing within the basin.[23] The first rail link to outside the basin was the Baoji–Chengdu Railway, completed in 1961 to connect with Shaanxi province across the Qin Mountains to the north.[24] The basin was also connected with Yunnan to the southwest in 1970, Hubei to the east in 1979, and Guizhou to the south in 2001. In the 21st century, many high-speed rail lines have been built or planned for the Sichuan Basin including the Chengdu-Guiyang and Chengdu-Xi'an lines.[25][26]

Highway construction within Sichuan Basin intensified in the 21st century. Expressways through the basin include the G5, G42, G50, G65, G75, G76, G85, and G93.[27] All expressways that connect the Sichuan Basin with other parts of China have been designed to utilize a series of tunnels and bridges to cross the mountainous surrounding terrain. Notable examples include the 18 km (11 mi) long Zhongnanshan Tunnel through the Qin Mountains to the north and the 500 m (1,600 ft) high Sidu River Bridge through the Wu Mountains to the east.

Maps gallery

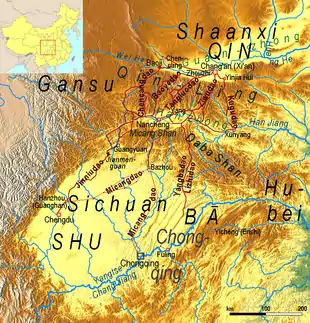

Map of the Yangtze River drainage basin with the Sichuan Basin in the centre

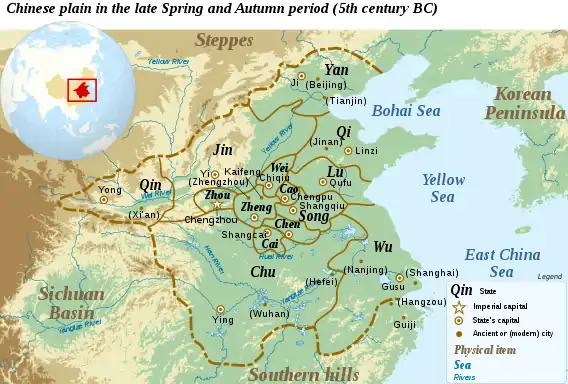

Map of the Yangtze River drainage basin with the Sichuan Basin in the centre Map showing the second Shu State in the Sichuan Basin during the Three Kingdoms period

Map showing the second Shu State in the Sichuan Basin during the Three Kingdoms period Sichuanese dialects are spoken in the Sichuan Basin and surrounding areas

Sichuanese dialects are spoken in the Sichuan Basin and surrounding areas The 4th century BC Shu Roads connected Sichuan Basin with the Yellow River valley (Shaanxi)

The 4th century BC Shu Roads connected Sichuan Basin with the Yellow River valley (Shaanxi) Sichuan Basin in relation to Southeast Asia and the eastern part of South Asia, with the Tea Horse Road routes highlighted in red

Sichuan Basin in relation to Southeast Asia and the eastern part of South Asia, with the Tea Horse Road routes highlighted in red

See also

References

- "Sichuan Basin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- National Physical Atlas of China. Beijing, China: China Cartographic Publishing House. 1999. ISBN 978-7503120404.

- Atlas of China. Beijing, China: SinoMaps Press. 2006. ISBN 9787503141782.

- Hsieh, Chiao-min; Hsieh, Jean Kan (1995). China: A Provincial Atlas. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster MacMillan. ISBN 978-0028971841.

- Justman, Hope (2007). Guide to Hiking China's Old Road to Shu. iUniverse. ISBN 9780595425518.

- "Haze in the Sichuan Basin". Earth Observatory. NASA. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- Zhang, Zhongjie; Yuan, Xiaohui; Chen, Yun; Tian, Xiaobo; Kind, Rainier; Li, Xueqing; Teng, Jiwen (April 2010). "Seismic signature of the collision between the east Tibetan escape flow and the Sichuan Basin". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 292 (3–4): 254–264. Bibcode:2010E&PSL.292..254Z. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2010.01.046.

- "Sichuan Basin". GES DISC. NASA. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- Li, K; Liu, J.; Yang, C.; Hu, F. (2011). "Dinosaur assemblages from the Middle Jurassic Shaximiao Formation and Chuanjie Formation in the Sichuan-Yunnan Basin, China". Volumina Jurassica. 9 (9): 21–42.

- "Sichuan Basin evergreen broadleaf forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- "Qionglai-Minshan conifer forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- "Daba Mountains evergreen forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Ma, Jinshuang; Shao, Guofan (2003). "Rediscovery of the 'first collection' of the 'Living Fossil', Metasequoia glyptostroboides". Taxon. 52 (3): 585–8. doi:10.2307/3647458. JSTOR 3647458.

- Keay, John (2009). China: A History. HarperCollins UK. ISBN 9780007221783.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2010). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521124331.

- Rowe, William T. (2006). Crimson Rain: Seven Centuries of Violence in a Chinese County. Stanford University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0804754965.

- Entenmann, Robert Eric (1982). Migration and settlement in Sichuan, 1644-1796. Harvard University.

- China's Southwest. Lonely Planet. 2007. ISBN 9781741041859.

- Energy Citations Database (ECD) - - Document #7024946

- Sichuan Sheng Dituce. Beijing, China: Star Map Press. 2013. ISBN 9787547109151.

- Johnston, Brian (2006). Boxing with Shadows: Travels in China. Melbourne University Publishing. p. 140.

- Ryavec, Karl E. (2015). A Historical Atlas of Tibet. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226732442.

- "新中国档案:成渝铁路--新中国的第一条铁路". CCTV. Xinhua News Agency. 11 August 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- (Chinese) "第八期 宝成铁路" 中国制造之科技" Accessed 2017-10-06

- Qiao, Han; Xi, Fan (16 August 2017). "Chinese high-speed rail expansion on the fast track". International Railway Journal. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- "China to build Xi'an-Chengdu high-speed railway". China Daily. Xinhua. 16 January 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- China Highway Atlas. Beijing, China: China Communications Press. 2014. ISBN 9787114060656.