Qiangic languages

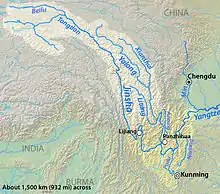

Qiangic (Ch'iang, Kyang, Tsiang, Chinese: 羌語支, "Qiang language group"; formerly known as Dzorgaic) is a group of related languages within the Sino-Tibetan language family. They are spoken mainly in Southwest China, including Sichuan, Tibet and Yunnan. Most Qiangic languages are distributed in the prefectures of Ngawa, Garzê, Ya'an and Liangshan in Sichuan with some in Northern Yunnan as well.

| Qiangic | |

|---|---|

| Dzorgaic | |

| Geographic distribution | China |

| Linguistic classification | Sino-Tibetan

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | naqi1236 (Na–Qiangic) qian1263 (Qiangic) |

Qiangic speakers are variously classified as part of the Qiang, Tibetan, Pumi, Nakhi and Mongol ethnic groups by the People's Republic of China.

The extinct Tangut language of the Western Xia is considered to be Qiangic by some linguists, including Matisoff (2004).[1] The undeciphered Nam language of China may possibly be related to Qiangic.

Lamo, Larong and Drag-yab, a group of three closely related Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in Chamdo, Eastern Tibet, may or may not be Qiangic.[2][3][4]

Classification

Sun (1983)

Sun Hongkai (1983)[5] proposes two branches, northern and southern:

- Northern: Northern Qiang (Máwō), Pumi (Prinmi), Muya (Minyag), Tangut (extinct; attested 1036–1502)

- Southern: Southern Qiang (Táopíng).

Sun groups other, poorly described Qiangic languages as:

Matisoff (2004)

Matisoff (2004)[1] states that Jiarongic is an additional branch:

Matisoff (2004) describes Proto-Tibeto-Burman *-a > -i as a typical sound change in many Qiangic languages, and refers to this vowel heightening as "brightening." Yu (2012)[6] also notes that "brightening" is a defining innovation in Proto-Ersuic, the reconstructed ancestor of the Ersuic languages.

Thurgood and La Polla (2003)

Thurgood and La Polla (2003) state that the inclusion of Qiang, Prinmi, and Muya is well supported, but that they do not follow Sun's argument for the inclusion of Tangut. Matisoff (2004), however, claims Tangut demonstrates a clear relationship.[7] The unclassified language Baima may also be Qiangic or may retain a Qiangic substratum after speakers shifted to Tibetan.[8]

Some other lesser-known, unclassified Qiangic peoples and languages include the following:[9]

- Bolozi 玻璃哦子/博罗子: 2,000 people; in Xiao Heshui Village 小河水村, west of Songpan; also as far south as Wenchuan Township 汶川乡.[10] Sun Hongkai (2013:80-82)[11] identifies Bolozi 博罗子 as a Northern Qiang variety, belonging to the Cimulin 茨木林 dialect.

- Ming 命: 10,000 people; mixed Chinese in Mao County and Wenchuan County, Sichuan[12]

- Xiangcheng 乡城: 10,000 people in and around Xiangcheng Township 乡城, Garzê Prefecture[13][14]

Sun (2001)

Sun Hongkai (2001)[15] groups the Qiangic languages are follows.

Jacques & Michaud (2011)

Guillaume Jacques & Alexis Michaud (2011)[16] argue for a Na–Qiangic branch, which itself forms a Burmo-Qiangic branch together with Lolo–Burmese. Na–Qiangic comprises three primary branches, which are Ersuish (or Ersuic), Naic (or Naxish), and [core] Qiangic. Similarly, David Bradley (2008)[17] also proposed an Eastern Tibeto-Burman branch that includes Burmic (AKA Lolo-Burmese) and Qiangic. The position of Guiqiong is not addressed.

- Na–Qiangic

Chirkova (2012)

However, Chirkova (2012) casts doubt on the validity of Qiangic as a coherent branch, instead considering Qiangic to be a diffusion area. Chirkova considers the following four languages to be part of four separate Tibeto-Burman branches:[18]

Both Shixing and Namuzi are both classified as Naic (Naxi) by Jacques & Michaud (2011), but Naic would not be a valid genetic unit in Chirkova's classification scheme since Shixing and Namuzi are considered by Chirkova to not be part of a single branch.

Yu (2012)

Yu (2012:218)[6] notes that Ersuic and Naish languages share some forms that are not found in Lolo-Burmese or “core” Qiangic (Qiang, Prinmi, and Minyak). As a result, “Southern Qiangic” (Ersuic, Namuyi, and Shixing) may be closer to Naish than it is to “core” Qiangic. Together, Southern Qiangic and Naish could form a wider “Naic” group that has links to both Lolo-Burmese to the south and other Qiangic languages to the north.

Obsolete names

Shafer (1955) and other accounts of the Dzorgaic/Ch'iang branch[19] preserve the names Dzorgai, Kortsè, Thochu, Outer/Outside Man-tze, Pingfang from the turn of the century. The first three were Northern Qiang, and Outside Mantse was Southern Qiang.[20]

When Jiarongic is included as a branch of Qiangic, but distinct from the non-Jiarongic languages, the label "Dzorgaic" may be used for Qiang proper.

Hsi-fan (Xifan) is an ethnic name, meaning essentially 'Tibetan'; the people speak Qiangic or Jiarongic languages such as Qiang, Ergong/Horpa, Ersu, Guiqiong, Shixing, Zhaba, Namuyi, Muya/Minyak, and Jiarong, but not Naxi/Moso, Pumi, or Tangut. The term has not been much used since language surveys of the 1980s resulted in sufficient data for classification.

Distribution

Qiangic languages are spoken mainly in western Sichuan and northwestern Yunnan provinces of China. Sun Hongkai (2013) lists the following watersheds (riverine systems) and the respective Qiangic languages spoken there.[11]

- Upper Jialing River watershed 嘉陵江上游地区: Baima

- Min River watershed 岷江流域: Qiang (including Boluozi 博罗子)

- Dadu River watershed 大渡河流域: Guiqiong, Ersu

- Yalong River watershed 雅砻江流域: Ergong, Zhaba, Muya, Namuyi

- Jinsha River watershed 金沙江流域: Shixing, Pumi

See also

References

- Matisoff, James. 2004. "Brightening" and the place of Xixia (Tangut) in the Qiangic subgroup of Tibeto-Burman

- Suzuki, Hiroyuki and Tashi Nyima. 2018. Historical relationship among three non-Tibetic languages in Chamdo, TAR. Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018). Kyoto: Kyoto University.

- Zhao, Haoliang. 2018. A brief introduction to Zlarong, a newly recognized language in Mdzo sgang, TAR. Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018). Kyoto: Kyoto University.

- Jacques, Guillaumes. 2016. Les journées d'études sur les langues du Sichuan.

- Sun, Hongkai. (1983). The nationality languages in the six valleys and their language branches. Yunnan Minzuxuebao, 3, 99-273. (Written in Chinese).

- Yu, Dominic. 2012. Proto-Ersuic. Ph.D. dissertation. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, Department of Linguistics.

- James Matisoff, 2004. "Brightening" and the place of Xixia (Tangut) in the Qiangic subgroup of Tibeto-Burman (Archived 2015-06-08 at WebCite)

- Katia Chirkova, 2008, "On the position of Báimǎ within Tibetan", in Lubotsky et al (eds), Evidence and Counter-Evidence, vol. 2.

- "China". asiaharvest.org. Archived from the original on 2013-08-01.

- "Bolozi" (PDF). Asaiharest.org. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Sun Hongkai. 2013. Tibeto-Burman languages of eight watersheds [八江流域的藏缅语]. Beijing: China Social Sciences Academy Press.

- "Ming" (PDF). Asaiharest.org. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "Xiangcheng" (PDF). Asaiharest.org. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "Xiangcheng" (PDF). Asaiharest.org. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Sūn Hóngkāi 孙宏开. 2001. 論藏緬語族中的羌語支語言 Lùn Zàng-Miǎn yǔzú zhōng de Qiāngyǔzhī yǔyán [On language of the Qiangic branch in Tibeto-Burman]. Language and linguistics 2:157–181.

- Jacques, Guillaume, and Alexis Michaud. 2011. "Approaching the historical phonology of three highly eroded Sino-Tibetan languages." Diachronica 28:468-498.

- Bradley, David. 2008. The Position of Namuyi in Tibeto-Burman.

- Chirkova, Katia (2012). "The Qiangic subgroup from an areal perspective: a case study of languages of Muli" (PDF). Language and Linguistics. 13 (1): 133–170.

- Such as Barley (1997) (Archived 2015-06-08 at WebCite)

- UC Berkeley, 1992, Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, vol. 15, pp. 76–77.

Bibliography

- Bradley, David (1997). Tibeto-Burman languages and classification. In D. Bradley (Ed.), Papers in South East Asian linguistics: Tibeto-Burman languages of the Himalayas (No. 14, pp. 1–71). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Miyake, Marc. 2015. What is the origin of uvularization in Qiang?

- Miyake, Marc. 2012. Nasal codas as clues for the stratification of Chinese loanwords in Ronghong Qiang.

- Miyake, Marc. 2011. Danger a-head for the 2 X 2 hypothesis.

- Miyake, Marc. 2011. fm-.

- Sun, Hongkai (1983). The nationality languages in the six valleys and their language branches. Yunnan Minzuxuebao, 3, 99-273. (Written in Chinese).

- Sun Hongkai (Academy of Social Sciences of China Institute of Nationality Studies) (1990). "Languages of the Ethnic Corridor in Western Sichuan" (" (Archive). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, 13(1), 1-31. English translation by Jackson T.-S. Sun (University of California Berkeley and Academia Sinica).

- Sun Hongkai 孙宏开. 2016. Zangmian yuzu Qiang yuzhi yanjiu 藏缅语族羌语支研究. Beijing: China Social Sciences Academy Press 中国社会科学出版社. ISBN 9787516176566