Siraj ud-Daulah

Mirza Muhammad Siraj-ud-Daulah (Persian: مرزا محمد سراج الدولہ, Bengali: মির্জা মুহাম্মদ সিরাজউদ্দৌলা; 1733 – 2 July 1757), commonly known as Siraj-ud-Daulah[lower-alpha 1] or Siraj ud-Daula,[4] was the last independent Nawab of Bengal. The end of his reign marked the start of British East India Company rule over Bengal and later almost all of the Indian subcontinent.

Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah | |

|---|---|

| Mansur-ul-Mulk (Victory of the Country) Siraj ud-Daulah (Light of the State) Hybut Jang (Horror in War) | |

Siraj-ud-Daulah | |

| 5th Nawab Nazim of Bengal,Bihar and Orissa | |

| Reign | 9 April 1756 – 23 June 1757 |

| Predecessor | Alivardi Khan |

| Successor | Mir Jafar |

| Full name

Nawab Mirza Muhammad Siraj ud-Daulah | |

| Native name | সিরাজউদ্দৌলা |

| Born | 1733. Murshidabad, Bengal Subah |

| Died | 2 July 1757 (aged 23-24) Murshidabad, Company Raj |

| Cause of death | Execution, Capital Punishment |

| Buried | Khushbagh, Murshidabad |

| Spouse(s) | Lutfunnisa Begum, Zaibunnisa Begum, Umdadunnisa Begum |

| Issue

Qudsia Begum (After Marriage), Shahzadi Umme Zohra (Before Marriage) | |

| Father | Zain ud-Din Ahmed Khan also known as Mirza Muhammad Hashim |

| Mother | Amina Begum |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Nawab of Bengal |

| Rank | Nawabzada, Nawab |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Plassey |

Siraj succeeded his maternal grandfather, Alivardi Khan as the Nawab of Bengal in April 1756 at the age of 23. Betrayed by Mir Jafar, then commander of Nawab's army, Siraj lost the Battle of Plassey on 23 June 1757. The forces of the East India Company under Robert Clive invaded and the administration of Bengal fell into the hands of the company.

Birth and family history

Siraj was born to Shia Muslim family of Zain ud-Din Ahmed Khan and Amina Begum in 1733 and soon after his birth, Siraj's maternal grandfather, was appointed the Deputy Governor of Bihar. Accordingly, he was raised at the Nawab's palace with all necessary education and training suitable for a future Nawab. Young Siraj also accompanied Alivardi on his military ventures against the Marathas in 1746. In 1750 Siraj revolted against his grandfather, Alivardi Khan, and seized Patna, but quickly surrendered and was forgiven.[5] Siraj was regarded as the "fortune child" of the family. Since birth Siraj, received the special affection of his grandfather. In May 1752, Alivardi Khan declared Siraj as his successor. Alivardi Khan died at 5am on 9 April 1756 at the age of eighty.[5]

Reign as Nawab

Siraj-ud-Daulah's nomination to the Nawab ship aroused the jealousy and enmity of his maternal aunt, Ghaseti Begum (Mehar-un-nisa Begum), Mir Jafar, Jagat Seth, Mehtab Chand and Shaukat Jung (Siraj's cousin). Ghaseti Begum possessed huge wealth, which was the source of her influence and strength. Apprehending serious opposition from her, Siraj ud-Daulah seized her wealth from Motijheel Palace and placed her under confinement. The Nawab also made changes in high government positions giving them his own favourites. Mir madan was appointed Bakshi (Paymaster of the army) in place of Mir Jafar. Mohanlal was elevated to the rank of peshkar of his Dewan Khana and he exercised great influence in the administration. Eventually, Siraj suppressed Shaukat Jang, governor of Purnia, who was killed in a clash.

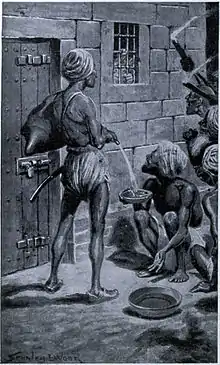

Black Hole of Calcutta

Siraj, as the direct political disciple of his grandfather, was aware of the global British interest in colonization, and hence resented the British politico-military presence in Bengal represented by the English East India Company. He was angered at the company's alleged involvement with and instigation of some members of his own court to a conspiracy to oust him. His charges against the company were broadly threefold. Firstly, that they strengthened the fortification around the Fort William without any intimation or approval; secondly, that they grossly abused trade privileges granted them by the Mughal rulers – which caused heavy loss of customs duties for the government; and thirdly, that they gave shelter to some of his officers, for example, Krishnadas, son of Rajballav, who fled Dhaka after misappropriating government funds. Hence, when the East India Company began further enhancement of military strength at Fort William in Calcutta, Siraj ud-Daulah ordered them to stop. The Company did not heed his directives; consequently, Siraj retaliated and captured Kolkata (for a short while renamed Alinagar) from the British in June 1756. The Nawab gathered his forces together and took Fort William. The captives were placed in the prison cell as a temporary holding by a local commander, but there was confusion in the Indian chain of command, and the captives were left there overnight, and many died. Contemporary British accounts of the ordeal run a considerable risk of embellishment. Actually the East India Company tried their best to propagate a false story of black hole killing among the people to raise them against Nawab Siraj ud-Daula.

Sir William Meredith, during the Parliamentary inquiry into Robert Clive's actions in India, vindicated Siraj ud-Daulah of any charge surrounding the Black Hole incident: "A peace was however agreed upon with Surajah Dowlah; and the persons who went as ambassadors to confirm that peace formed the conspiracy, by which he was deprived of his kingdom and his life."[6]

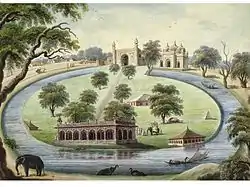

Nizamat Imambara

Shi'ism was introduced to Bengal during the governorship of Shah Shuja (1641–1661 AD), son of Shah Jahan. From 1707 AD to 1880 AD, the Nawabs of Bengal were Shias. [7][8] [9] They built huge Imambargahs, including the biggest of the Subcontinent built by Nawab Siraj-ud Daula, the Nizammat Imambara. The nawabs of Bengal and Iranian merchants in Bengal patronised azadari and the political capital Murshidabad and the trading hub Hoogly attracted Shia scholars from within and outside India.[10]

Conspiracy

The Nawab was infuriated on learning of the attack on Chandernagar. His former hatred of the British returned, but he now felt the need to strengthen himself by alliances against the British. The Nawab was plagued by fear of attack from the north by the Afghans under Ahmad Shah Durrani and from the west by the Marathas. Therefore, he could not deploy his entire force against the British for fear of being attacked from the flanks. A deep distrust set in between the British and the Nawab. As a result, Siraj started secret negotiations with Jean Law, chief of the French factory at Cossimbazar, and de Bussy. The Nawab also moved a large division of his army under Rai Durlabh to Plassey, on the island of Cossimbazar 30 miles (48 km) south of Murshidabad.[11][12][13][14]

Popular discontent against the Nawab flourished in his own court. The Seths, the traders of Bengal, were in perpetual fear for their wealth under the reign of Siraj, contrary to the situation under Alivardi's reign. They had engaged Yar Lutuf Khan to defend them in case they were threatened in any way.[15] William Watts, the Company representative at the court of Siraj, informed Clive about a conspiracy at the court to overthrow the ruler. The conspirators included Mir Jafar, the paymaster of the army, Rai Durlabh, Yar Lutuf Khan and Omichund (Amir Chand), a Sikh merchant, and several officers in the army.[16] When communicated in this regard by Mir Jafar, Clive referred it to the select committee in Calcutta on 1 May. The committee passed a resolution in support of the alliance. A treaty was drawn up between the British and Mir Jafar to raise him to the throne of the Nawab in return for support to the British in the field of battle and the bestowal of large sums of money upon them as compensation for the attack on Calcutta. On 2 May, Clive broke up his camp and sent half the troops to Calcutta and the other half to Chandernagar.[17][18][19][20]

Mir Jafar and the Seths desired that the confederacy between the British and himself be kept secret from Omichund, but when he found out about it, he threatened to betray the conspiracy if his share was not increased to three million rupees (£300,000). Hearing of this, Clive suggested an expedient to the committee. He suggested that two treaties be drawn – the real one on white paper, containing no reference to Omichund and the other on red paper, containing Omichund's desired stipulation, to deceive him. The Members of the Committee signed on both treaties, but Admiral Watson signed only the real one and his signature had to be counterfeited on the fictitious one.[21] Both treaties and separate articles for donations to the army, navy squadron and committee were signed by Mir Jafar on 4 June.[22][23][24][25]

Lord Clive testified and defended himself thus before the House of Commons of Parliament on 10 May 1773, during the Parliamentary inquiry into his conduct in India:

"Omichund, his confidential servant, as he thought, told his master of an agreement made between the English and Monsieur Duprée [may be a mistranscription of Dupleix] to attack him, and received for that advice a sum of not less than four lacks of rupees. Finding this to be the man in whom the nawab entirely trusted, it soon became our object to consider him as a most material engine in the intended revolution. We, therefore, made such an agreement as was necessary for the purpose, and entered into a treaty with him to satisfy his demands. When all things were prepared, and the evening of the event was appointed, Omichund informed Mr Watts, who was at the court of the nawab, that he insisted upon thirty lacks of rupees, and five per cent. upon all the treasure that should be found; that, unless that was immediately complied with, he would disclose the whole to the nawab; and that Mr. Watts, and the two other English gentlemen then at the court, should be cut off before the morning. Mr Watts, immediately on this information, dispatched an express to me at the council. I did not hesitate to find out a stratagem to save the lives of these people, and secure success to the intended event. For this purpose, we signed another treaty. The one was called the Red, the other the White treaty. This treaty was signed by everyone, except admiral Watson; and I should have considered myself sufficiently authorised to put his name to it, by the conversation I had with him. As to the person who signed Admiral Watson's name to the treaty, whether he did it in his presence or not, I cannot say; but this I know, that he thought he had sufficient authority for so doing. This treaty was immediately sent to Omichund, who did not suspect the stratagem. The event took place, and success attended it; and the House, I am fully persuaded, will agree with me, that, when the very existence of the company was at stake, and the lives of these people so precariously situated, and so certain of being destroyed, it was a matter of true policy and of justice to deceive so great a villain."[26][27]

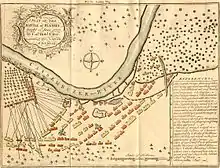

The Battle of Plassey

The Battle of Plassey (or Palashi) is widely considered the turning point in the history of the subcontinent and opened the way to eventual British domination. After Siraj-ud-Daulah's conquest of Calcutta, the British sent fresh troops from Madras to recapture the fort and avenge the attack. A retreating Siraj-ud-Daulah met the British at Plassey. He had to make camp 27 miles away from Murshidabad. On 23 June 1757 Siraj-ud-Daulah called on Mir Jafar because he was saddened by the sudden fall of Mir Mardan who was a very dear companion of Siraj in battles. The Nawab asked for help from Mir Jafar. Mir Jafar advised Siraj to retreat for that day. The Nawab made the blunder in giving the order to stop the fight. Following his command, the soldiers of the Nawab were returning to their camps. At that time, Robert Clive attacked the soldiers with his army. At such a sudden attack, the army of Siraj became indisciplined and could think of no way to fight. So all fled away in such a situation. Betrayed by a conspiracy plotted by Jagat Seth, Mir Jafar, Krishna Chandra, Omichund etc., he lost the battle and had to escape. He rode away and went first to Murshidabad, specifically to Heerajheel or Motijheel, his palace at Mansurganj. He ordered his principal commanders to engage their troops for his safety, but as he was bereft of power due to the loss at Plassey, they were reluctant to offer unquestioning support. Some advised him to deliver himself up to the English, but Siraj equated this with treachery. Others proposed he should encourage the army with greater rewards, and this he seemed to approve of. Yet the numbers in his retinue were considerably diminished. Soon he dispatched most of the women of his harem to Purneah, under the protection of Mohanlal, with gold and elephants. Then, with his principal consort Lutf-un-Nisa and very few attendants, Siraj began his escape towards Patna by boat, but was eventually arrested by Mir Jafar's soldiers.[28]

Death

_being_a_synopsis_of_the_history_of_Murshidabad_for_the_last_two_centuries%252C_to_which_are_appended_notes_of_places_and_objects_of_interest_at_Murshidabad_(1905)_(14776529292).jpg.webp)

Siraj-ud-Daulah was executed on 2 July 1757 by Mohammad Ali Beg under orders from Mir Miran, son of Mir Jafar in Namak Haram Deorhi as part of the agreement between Mir Jafar and the British East India Company.

Siraj-ud-Daulah's tomb is located at Khushbagh, Murshidabad. It is marked with a simple but elegant one-storied mausoleum, surrounded by gardens.[29]

Critics and legacy

Siraj ud-Daulah is usually seen as a freedom fighter in modern India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan for his opposition to the beginning of British rule over India.

After the death of Alivardii Khan, his immature grandson became the nawab of Bengal, taking the name Miirza Mohammed Siraj-Ud-Daola. In addition to his young age, he had many kinds of defects in his character and conduct.

Two Shia historians who were in favour of Mir Jafar wrote of Siraj ud-Daulah.

Ghulam Husain Salim wrote:

Owing to Siraju-d-daulah's harshness of temper and indulgence in violent language, fear and terror had settled on the hearts of everyone to such an extent, that no one among the generals of the army or the noblemen of the City was free from anxiety. Among his officers, whoever went to wait on Siraju-d-daulah despaired of life and honour, and whoever returned without being disgraced and ill-treated offered thanks to God. Siraju-d-daulah treated all the noblemen and capable generals of Mahabat Jang with ridicule and drollery and bestowed on each some contemptuous nick-name that ill-suited any of them. And whatever harsh expressions and abusive epithet came to his lips, Siraju-d-daulah uttered them unhesitatingly in the face of everyone, and no one had the boldness to breathe freely in his presence.

Ghulam Husain Tabatabai wrote of Siraj ud-Daulah:

Making no distinction betwixt vice and virtue ... he carried defilement wherever he went; and like a man alienated in his mind he made the houses of men and women of distinction the scenes of his profli¬gacy, without minding either rank or station. In a little time, he became as detested as Pharao. People on meeting him by chance used to say, God save us from him!

Sir William Meredith, during the Parliamentary inquiry into Robert Clive's actions in India, defended the character of Siraj-ud Daulah:

Siraj-ud-Daulah is indeed reported to have been a very wicked, and a very cruel prince, but how he deserved that character does not appear in fact. He was very young, not 20 years old when he was put to death—and the first provocation to his enmity was given by the English. It is true, that when he took Calcutta a very lamentable event happened, I mean the story of the Black Hole; but that catastrophe can never be attributed to the intention, for it was without the knowledge of the prince. I remember a similar accident happening in St. Martin's roundhouse, but it should appear very ridiculous, were I, on that account, to attribute any guilt or imputation of cruelty to the memory of the late king, in whose reign it happened. A peace was however agreed upon with Suraj-ud-Daulah; and the persons who went as ambassadors to confirm that peace formed the conspiracy, by which he was deprived of his kingdom and his life.[6]

It is possible that Siraj-ud-Daulah was trained in the martial arts by the Pindari, whom he deployed on several occasions. A painting by Francis Hayman displaying a half-naked corpse of Siraj indicates that he was a Nawab who behaved like a Pindari.

Namesakes

- Siraj ud Daula College, Karachi, Pakistan

- Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah Government College, Natore,[31] Bangladesh

- Masjid-e-Siraj ud-Daulah, Bangladesh

- Siraj-ud-Daula Road, Karachi[32]

- Nabab Siraj ud-Daulah Road, Chittagong, Bangladesh

- Nawab Siraj-Ud-Daulah Sarani, Kolkata, India[33]

- Siraj ud-Daulah Park, Old Dhaka,[34] Bangladesh

- Siraj-ud-Doula Hall, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University,[35] Bangladesh

- Nawab Siraj Ud-Daulah College, Kushtia, Bangladesh

- Siraj-ud-Daula Road, Kushtia,[36] Bangladesh

- Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah Hospital,[37] Bangladesh

- Nawab Siraj ud Daulah Road, Narayanganj, Bangladesh

In popular culture

- Ami Sirajer Begam (Novel) (1960), Historical novel set in Bengal.[38]

- Sirajuddaula (1965), Theater by Sikandar Abu Zafar[39][40]

- Nawab Sirajuddaula (1967), an Indian Bengali Film directed by Ramchandra Thakur featuring Bharat Bhushan[41]

- Nawab Sirajuddaula (1967), a Bangladeshi Movie directed by Khan Ataur Rahman featuring Anwar Hossain (actor)

- Ami Sirajer Begam (1973), an Indian Bengali Film directed by Sushil Mukhopadhyay featuring Ajitesh Bandopadhyay

- Sirajuddaula (1986), Musical opera by Nimalendu Lahiri [42][43]

- Nawab Sirajuddaula (1989), remake of the 1967 Movie

- Ami Sirajer Begum (2018), Indian Bengali television Historical soap opera.

See also

Notes

- Other spellings exist including the corruption "Sir Roger Dowler"[2] which is also used in phrases such as "Sir Roger Dowler method" referring to early non-systematic and distorting Romanisation schemes for Devanagari script.[3]

- ^ Ġulām Ḥusain chaklim (1902). The Riyazu-s-salatin, A History of Bengal. Translated by Salam, Maulavi Abdus. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society. p. 363-370.

- ^ Seid-Gholam-Hossein-Khan (1926). The Sëir Mutaqherin or Review of Modern Times. Volume II. Calcutta: R. Cambray & Co. link to searchable text at the Packard Humanities Institute

References

- Rai, R. History. FK Publications. p. 44. ISBN 9788187139690.

- Abram Smythe Palmer. Folk-etymology: A Dictionary of Verbal Corruptions Or Words Perverted in Form Or Meaning, by False Derivation Or Mistaken Analogy. G. Bell and Sons, 1882. p. 557.

- Francis Henry Skrine. Life of Sir William Wilson Hunter, K.C.S.I., M.A., LL.D., a vice-president of the Royal Asiatic Society, etc. Longmans, Green, and Co., 1901. p. 205.

- Dalrymple, W. (2019),The Anarchy p78, London: Bloombsbury

- Dalrymple, W. (2019),The Anarchy p87, London: Bloombsbury

- Cobbett, William; Hansard, Thomas Curson (1813). The Parliamentary History of England from the Earliest Period to the Year 1803. T.C. Hansard. pp. 449–. ISBN 9780404016500.

- S. A. A. Rizvi, A Socio-Intellectual History of Isna Ashari Shi'is in India, Vol. 2, pp. 45–47, Mar'ifat Publishing House, Canberra (1986).

- K. K. Datta, Ali Vardi and His Times, ch. 4, University of Calcutta Press, (1939)

- Andreas Rieck, The Shias of Pakistan, p. 3, Oxford University Press, (2015).

- Andreas Rieck, "The Shias of Pakistan", p. 3, Oxford university press, (2015).

- Harrington, p. 25

- Mahon, p. 337

- Orme 1861, p. 145

- Malleson, pp. 48–49

- Bengal, v.1, p. clxxxi

- Bengal, v.1, pp. clxxxiii–clxxxiv

- Malleson, pp. 49–51

- Harrington, pp. 25–29

- Mahon, pp. 338–339

- Orme 1861, pp. 147–149

- Bengal, v.1, pp. clxxxvi–clxxxix

- (Orme 1861, pp. 150–161)

- Harrington, p. 29

- Mahon, pp. 339–341

- Bengal, v.1, pp. cxcii–cxciii

- Cobbett, William; Parliament, Great Britain (1813). The Parliamentary history of England from the earliest period to the year 1803, Volume 17. p. 876. ISBN 9780404016500.

- The gentleman's magazine, and historical chronicle, Volume 43. 1773. pp. 630–631.

- "We all know Siraj-ud-Daulah lost the Battle of Plassey. How did he escape afterwards?". Scroll.in. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Basu, Saurab. "Trip Taken from June – 10th to 12th - 2006". Murshidabad – The Land of the Legendary ‘Siraj-ud-Daulah’ Unveiled. History of Bengal. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Sarkar, Prabhat Ranjan (1996). Shabda Cayanika, Part 1 (First English ed.). Kolkata: Ananda Marga Publications. ISBN 81-7252-027-1.

- "Week-long agriculture technology fair begins in Natore". Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- "Siraj ud Daula Road, Karachi". pakistan-streets.openalfa.com.

- "Nawab Siraj-Ud-Daulah Sarani, West Bengal". indiaplacesmap.com.

- "6 suspected Huji operatives held in Dhaka". Prothom Alo.

- "Siraj-Ud-Doula Hall". Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University (SAU).

- "BGIC Branch Network - BGIC Ltd.BGIC Ltd".

- "4 hospitals fined, two of them asked to shut". The Daily Star. 17 October 2015.

- Shriparabat (31 March 1960). "Ami Sirajer Begum". Rupayani – via Google Books.

- http://web.dailyjanakantha.com/details/article/280339/সিকানদার-আবু-জাফরের-নাটক-সিরাজউদ্দৌলা-একটি-অনুভাবনা/

- "My Academy :: Digital Book". myacademybd.com.

- "Nawab Sirajuddaula (1967) - Review, Star Cast, News, Photos". Cinestaan.

- Various Artists - Topic (3 November 2014). "Sirajuddaula" – via YouTube.

- Array. "Sirajuddaula (Full Song) - Nirmalendu Lahiri, Sachin Sengupta, Sarajubala Devi - Download or Listen Free - JioSaavn" – via www.jiosaavn.com.

- Akhsaykumar Moitrayo, Sirajuddaula, Calcutta 1898

- BK Gupta, Sirajuddaulah and the East India Company, 1756–57, Leiden, 1962

- Kalikankar Datta, Sirajuddaulah, Calcutta 1971

- Orme, R. (1861), A history of the military transactions of the British nation in Indostan: from the year MDCCXLV; to which is prefixed A dissertation on the establishments made by Mahomedan conquerors in Indostan, 2

External links

Siraj ud-Daulah Born: 1733 Died: 2 July 1757 | ||

| Preceded by Alivardi Khan |

Nawab of Bengal 9 April 1756 – 2 June 1757 |

Succeeded by Mir Jafar |