State communications in the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The state communications in the Neo-Assyrian Empire allowed the Assyrian king and his officials to send and receive messages across the empire quickly and reliably. Messages were sent using a relay system (Assyrian: kalliu) which was revolutionary for the early first millennium BCE. Messages were carried by military riders who travelled on mules. At intervals the riders stopped at purpose-built stations, and the messages were passed to other riders with fresh mounts. The stations were positioned at regular intervals along the imperial highway system. Because messages could be transmitted without delay or waiting for riders to rest the system provided unprecedented communication speed, which was not surpassed in the Middle East until the introduction of the telegraph.

The efficiency of the system contributed to the Neo-Assyrian Empire's dominance in the Middle East and to maintaining cohesion throughout the empire. These Assyrian innovations were adopted by later empires, including the Achaemenid Empire which inherited and expanded the Assyrian communication network.

History

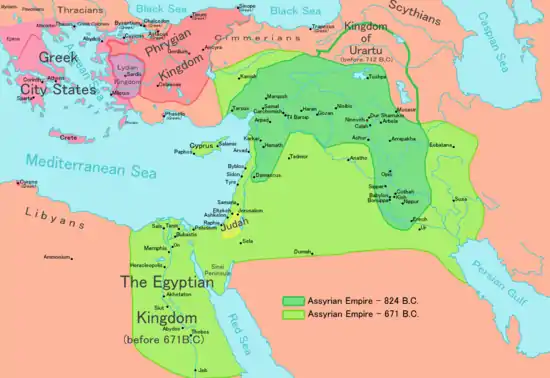

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was an Iron Age empire centered in Mesopotamia. The reign of Adad-nirari II (r. 911–891 BCE) was considered the start of the empire. He and his successors – up to the late seventh century BCE – expanded the empire to dominate most of the modern Middle East, from Egypt in the west to the Persian Gulf in the east.[1] As the empire grew, it introduced various administrative and infrastructural innovations, which became templates for later empires, including the Roman and Persian empires.[2]

The state communication system was developed to solve the challenges of governing a large empire. It probably originated during the reign of Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 BCE), when Assyria was already the largest power in the Middle East. In order to rule and maintain cohesion within the empire, the king, his court officials and his governors in the provinces needed a fast and reliable system to communicate.[3]

Components

Mule

The long-distance state messengers were mounted exclusively on mules. Assyria was the first civilization to use mules for this purpose. Mules are hybrids of a donkey father and a horse mother. They combine the strength of a horse and the ruggedness of a donkey. Their infertility and need of extensive training meant that they were expensive, but their strength, hardiness and low maintenance made them ideal for long-distance travel in the conditions and climates of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Mules were also good at swimming streams – a common obstacle throughout Mesopotamia. Riders in the Assyrian communication system typically travelled with two mules, so that they did not become stranded if one became lame, and to alternate mounts in order to keep them fresh.[5][4]

Relay riders

Official messages could either be sent by letter carried by a series of relay riders or by a trusted envoy.[6] The relay system (kalliu) was an Assyrian innovation and allowed for a much faster communication speed.[6] Rather than relying on a trusted envoy to travel the entire distance, in the relay system each individual rider covered only a segment of the route.[6] The segment ended at a station, where the rider passed the letter to a new rider with a fresh pair of mules.[6] Because animals and riders were changed at each stop without waiting for the previous ones to rest, messages were delivered much faster.[7] The riders and their mules were provided by the Assyrian military.[8]

Despite the speed of the relay system, trusted envoys were also used when communication speed was not vital, and were preferred for very sensitive messages or those which required on-the-spot responses. Sometimes both methods were used simultaneously, such as in the case of a surviving letter from then-crown prince Sennacherib to his father Sargon II.[6]

Road network

The Neo-Assyrian Empire built a highway system connecting all parts of the empire. These roads, called hūl šarri (or harran šarri in the Babylonian dialect, "the king's road"), might have grown out of the military roads used for campaigning. They were continuously expanded, with the largest expansion occurring between the reigns of Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 BCE) and Tiglathpileser III r. 745–727 BCE.[9]

Stations

To support the communication system, governors of the empire maintained a series of stations in their provinces at regular intervals along the king's road.[3] In Assyrian they were called bēt mardēti ("house of a route's stage").[3] At these stations riders passed their letters to new riders with fresh mules.[11] They were either located within established settlements, such as the one in Nippur, or in remote locations, where they constituted isolated settlements on their own.[3] The distances between stations were around 35 to 40 kilometers (22 to 25 miles).[8] The stations provided short-term shelter and supplies for riders, envoys and their animals.[10]

These stations were comparable to the later caravanserais built throughout the Muslim world for commercial travelers, in the sense that they were purpose-built to provide shelter for long distance travellers.[10] However, unlike the caravanserais, the Assyrian road stations were for the exclusive use of authorized state messages and not open to private travelers.[10] No surviving road stations have been identified or excavated[10] and historians only know their descriptions from Assyrian texts.[12]

Authorization and authentication

Use of the imperial postal system was restricted to messages from a set of high state officials. Professor of ancient near-eastern history Karen Radner estimated that it was available to a group of about 150 officials who were called the "Great Ones" of Assyria.[12] They all held a copy of the Assyrian royal seal which they stamped on messages to identify their authority.[12] The seal depicted the Assyrian king in combat with a rampant lion and was recognized throughout the empire.[13] Only letters carrying this seal could be sent using the state system.[8]

Speed

Radner estimated that a message from the western border province of Quwê (near modern-day Adana, Turkey) to the Assyrian heartland – 700 kilometres (430 mi) as the crow files and requiring the crossing the Euphrates, the Tigris and many tributaries, none of which had bridges – took less than five days to arrive. This communication speed was unprecedented and was not surpassed in the Middle East until the introduction of the telegraph to the region during the Ottoman era in 1865.[6][11]

Significance

The rapid long-distance communications between the imperial court and the provinces was important for the empire's cohesion and was one of the factors supporting the domination of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the Middle East.[14] Mario Liverani says that Assyria was an "empire of communications",[14] and Karen Radner opines that the imperial communication system "may well constitute Assyria's most important contribution to the art of government" and became "a standard tool in the administration of empires".[15]

The system introduced by the Assyrians were adopted by later empires.[16] The existing Assyrian network was considerably expanded by the Persian Empire.[17] The system was also the basis of the nineteenth century Pony Express in the United States.[18] The use of relays of anonymous messengers – instead of a trusted envoy who must travel the entire distance – was a practice that the Assyrians introduced and remains the basis of today's postal systems.[7]

References

Citations

- Encyclopædia Britannica 2017.

- Radner 2015b, p. 95.

- Radner 2012, Road stations across the empire.

- Radner 2012, The original hybrid transport technology.

- Radner 2018, 0:07.

- Radner 2015, p. 64.

- Radner 2018, 4:20.

- Radner 2018, 13:06.

- Kessler 1997, p. 130.

- Radner 2015, p. 63.

- Radner 2012, Making speed.

- Radner 2015, p. 65.

- Radner 2012, Authorisation needed.

- Kessler 1997, p. 129.

- Radner 2012, paragraph 1.

- Radner 2015, p. 68.

- Bertman 2003, p. 254.

- Bertman 2003, p. 210.

Bibliography

- Bertman, Stephen (2003). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-7481-5.

- Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (2017). "Assyria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Retrieved 2018-04-28.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kessler, Karlheinz (1997). ""Royal Roads" and other questions of the Neo-Assyrian communication system" (PDF). In S. Parpola; R. Whiting (eds.). Assyria 1995. Helsinki: Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project. pp. 129–136.

- Radner, Karen (2012). "The King's Road – the imperial communication network". Assyrian empire builders. University College London.

- Radner, Karen (2015). "Royal pen pals: the kings of Assyria in correspondence with officials, clients and total strangers (8th and 7th centuries BC)" (PDF). In S. Prochazka; L. Reinfandt; S. Tost (eds.). Official Epistolography and the Language(s) of Power. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press.

- Radner, Karen (2015b). Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871590-0.

- Radner, Karen (2018). Focus on Long-Distance Communications (video). Organising an Empire: The Assyrian Way. Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. Retrieved 2018-04-22 – via Coursera.