Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal, also spelled Assurbanipal,[9] Asshurbanipal[10] and Asurbanipal[9] (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: ![]() , Aššur-bāni-apli or Aššur-bāni-habal,[11][12] meaning "Ashur has given a son-heir")[13][14] was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Esarhaddon in 668 BC to his own death in 631 BC.[1][2][3] The fourth king of the Sargonid dynasty, Ashurbanipal is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria.

, Aššur-bāni-apli or Aššur-bāni-habal,[11][12] meaning "Ashur has given a son-heir")[13][14] was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Esarhaddon in 668 BC to his own death in 631 BC.[1][2][3] The fourth king of the Sargonid dynasty, Ashurbanipal is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria.

| Ashurbanipal | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Ashurbanipal, closeup from the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal | |

| King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | 669–631 BC[1][2][3] |

| Predecessor | Esarhaddon |

| Successor | Ashur-etil-ilani |

| Born | 685 BC[4][5] |

| Died | 631 BC[6] (aged c. 54) |

| Spouse | Libbali-sharrat |

| Issue | Ashur-etil-ilani Sinsharishkun Ninurta-sharru-usur |

| Akkadian | Aššur-bāni-apli Aššur-bāni-habal |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Esarhaddon |

| Mother | Unknown,[7] of Assyrian origin.[8] |

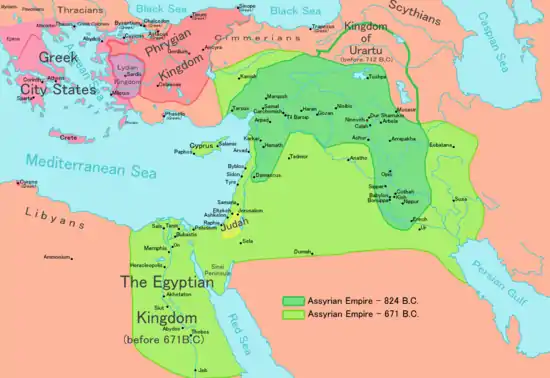

At the time of Ashurbanipal's reign, the Neo-Assyrian Empire was the largest empire that the world had ever seen and its capital, Nineveh, was probably the largest city on the planet. Selected as heir by his father in 672 BC despite not being the eldest son, Ashurbanipal ascended to the throne in 669 BC jointly with his elder brother Shamash-shum-ukin, who became king of Babylon. Much of the early years of Ashurbanipal's reign was spent fighting rebellions in Egypt, which had been conquered by his father.

The greatest campaigns of Ashurbanipal were those directed towards Elam, an ancient enemy of Assyria, and against Shamash-shum-ukin, who had expected to be an equal to Ashurbanipal and began to resent the overbearing control that his younger brother held over him. Elam was defeated in a series of campaigns in 665 BC and 647–646 BC, after which the cities of Elam were destroyed, its people slaughtered, and the land was left barren and undefended. Shamash-shum-ukin rebelled in 652 BC and assembled a coalition of Assyria's enemies to fight against Ashurbanipal alongside him, but was defeated by Ashurbanipal.

Ashurbanipal is most famous for the construction of the Library of Ashurbanipal, the first systematically organized library in the world. The king himself considered the library, a collection of over 30,000 clay tablets with texts of several genres, including religious documents, handbooks, and traditional Mesopotamian stories, as his greatest achievement. Ashurbanipal's library is the primary reason why texts such as the Epic of Gilgamesh managed to survive to the present day.

Background

Ashurbanipal was probably King Esarhaddon's fourth eldest son, younger than the crown prince Sin-nadin-apli and the other two sons Shamash-shum-ukin and Shamash-metu-uballit.[16] He also had an older sister, Serua-eterat, and several younger brothers.[17] Sin-nadin-apli died unexpectedly in 674 BC and Esarhaddon, who was keen to avoid a succession crisis as he himself had only ascended to the throne with great difficulty, soon started making new succession plans.[18] Esarhaddon entirely bypassed the third eldest son, Shamash-metu-uballit, possibly because this prince suffered from poor health.[19]

In May 672 BC, Ashurbanipal was appointed by Esarhaddon as the heir to Assyria and Shamash-shum-ukin was appointed as the heir to Babylonia.[9] The two princes arrived at the capital of Nineveh together and partook in a celebration with foreign representatives and Assyrian nobles and soldiers.[20] Promoting one of his sons as the heir to Assyria and another as the heir to Babylon was a new idea, for the past decades the Assyrian king had simultaneously been the King of Babylon.[21] Esarhaddon might have decided to split his titles between his sons since Esarhaddon's brothers had murdered his father Sennacherib and attempted to usurp the throne after Esarhaddon had been proclaimed as heir decades prior. By splitting rulership of the empire, he might have surmised that such jealousy and rivalry could be avoided.[22]

The choice to name a younger son as crown prince of Assyria, which was clearly Esarhaddon's primary title, and an older son as crown prince of Babylon might be explained by the mothers of the two sons. While Ashurbanipal's mother was likely Assyrian, Shamash-shum-ukin was the son of a woman from Babylon (though this is uncertain, Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin may have shared the same mother)[7] which might have had problematic consequences if Shamash-shum-ukin was to ascend to the Assyrian throne. Since Ashubanipal was the next oldest son, he then was the superior candidate to the throne. Esarhaddon might then have surmised that the Babylonians would be content with someone of Babylonian heritage as their king and as such set Shamash-shum-ukin to inherit Babylon and the southern parts of his empire instead.[8] Treaties drawn up by Esarhaddon are somewhat unclear as to the relationship he intended his two sons to have. It is clear that Ashurbanipal was the primary heir to the empire and that Shamash-shum-ukin was to swear him an oath of allegiance but other parts also specify that Ashurbanipal was not to interfere in Shamash-shum-ukin's affairs which indicates a more equal standing.[23]

After Ashurbanipal was appointed as crown prince, he began preparing himself to be a king by observing his father, learning etiquette and studying military tactics. Ashurbanipal also worked as a spymaster, compiling reports for his father based on information gathered from agents throughout the Assyrian Empire.[3] He was educated by the general Nabu-shar-usur and the scribe Nabu-ahi-eriba and developed an interest in literature and history. The crown prince mastered scribal and religious knowledge and became proficient in reading both his native Akkadian language and Sumerian. According to Ashurbanipal's own later accounts (his annals representing the major historical sources for his reign), Esarhaddon had favored him due to his intelligence and bravery.[9]

Because Esarhaddon was constantly ill, much of the administrative duties of the empire fell upon Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin during the last few years of their father's reign.[21] When Esarhaddon left to campaign against Egypt, Ashurbanipal became responsible for the affairs of the court and upon his father's death in 669 BC, full power was transferred to Ashurbanipal without any incidents.[9]

Reign

Early reign and Egyptian campaigns

After Esarhaddon's death in late 669 BC, Ashurbanipal became the Assyrian king as per his father's succession plans. In the spring of the next year, Shamash-shum-ukin was inaugurated as the king of Babylon and returned the statue of Bêl (Bêl, or Marduk, being the patron deity of Babylon) to the city, stolen by his grandfather King Sennacherib twenty years prior. Shamash-shum-ukin would rule at Babylon for sixteen years, apparently mostly peacefully in regards to his younger brother, but there would be repeated disagreements on the exact extent of his control.[6] Although Esarhaddon's inscriptions suggest that Shamash-shum-ukin should have been granted the entirety of Babylonia to rule, contemporary records only definitely prove that Shamash-shum-ukin held Babylon itself and its vicinity. The governors of some Babylonian cities, such as Nippur, Uruk and Ur, and the rulers in the Sea Land (the marshy lands in southern Sumer, near the shores of the Persian Gulf), all ignored the existence of a king in Babylon and saw Ashurbanipal as their monarch.[24]

After he and his brother had been properly inaugurated as monarchs, Ashurbanipal turned his attention towards Egypt.[4] Egypt had been conquered by Esarhaddon in 671 BC, one of Ashurbanipal's father's greatest accomplishments. Though Esarhaddon had placed loyal governors in charge of the new Egyptian territories and had captured most of the Egyptian royal court, including the son and wife of the Pharaoh, the Pharaoh Taharqa had escaped to Kush in the south.[25]

.jpg.webp)

In 669 BC, Taharqa had reappeared from the south and had inspired Egypt to attempt to free itself from Esarhaddon's control.[28] Esarhaddon had received word of this rebellion and learnt that even some of his own governors who he had appointed in Egypt had ceased to pay tribute to him and joined the rebels.[25] Esarhaddon had marched to defeat this rebellion but had died before reaching the Egyptian border.[28] To quell the threat, Ashurbanipal invaded Egypt in c. 667 BC, marching the Assyrian army as far south as Thebes, one of Egypt's ancient capitals, and sacking numerous revolting cities. Ashurbanipal's Rassam cylinder records the following:

In my first campaign I marched against Magan, Meluhha, and Taharqa, king of Egypt and Ethiopia, whom Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, the father who begot me, had defeated, and whose land he brought under his sway. This same Taharqa forgot the might of Ashur, Ishtar and the other great gods, my lords, and put his trust upon his own power. He turned against the kings and regents whom my own father had appointed in Egypt. He entered and took residence in Memphis, the city which my own father had conquered and incorporated into Assyrian territory.[29]

The rebellion was stopped and Ashurbanipal appointed as his vassal ruler in Egypt Necho I, who had been king of the city Sais, and Necho's son Psamtik I, who had been educated at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh during Esarhaddon's reign.[4]

Ashurbanipal left Egypt after his victory. The country was thus seen as vulnerable and Taharqa's nephew and designated successor Tantamani invaded Egypt in hopes of restoring his family to the throne. He met the forces of Necho at Memphis, the Egyptian capital, and though Tantamani was defeated, Necho also died in the battle. The situation quickly turned in Tantamani's favor as the Egyptians themselves rose up alongside him against Psamtik, who escaped into hiding. Hearing of this, Ashurbanipal again marched his army to Egypt and defeated Tantamani. In 663 BC Thebes, the stronghold of the Kushites in Egypt, was sacked for a third time in less than a decade, and Tantamani abandoned the campaign and escaped back to Kush.[4]

Victorious, Ashurbanipal made Psamtik the full Pharaoh of Egypt in 665 BC and granted him Assyrian garrisons throughout Egypt. The next few years saw Ashurbanipal occupied elsewhere, leading his army in Anatolia against Tabal, in the north against Urartu and in the south-east against Elam. With little attention given to Egypt, the kingdom would slowly slip away from Assyrian control without the need for a bloody conflict.[4]

First Elamite campaign

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

In 665 BC, the Elamite king Urtak launched a surprise attack against Babylonia, but was successfully driven back into Elam, dying shortly thereafter. Urtak was succeeded as Elamite king by Teumman, who was unrelated to the previous monarch and had to stabilize his rule by killing his political rivals. Three of Urtak's sons, chief rival claimants to the Elamite throne, escaped to Assyria and were harbored by Ashurbanipal, despite Teumman demanding them to be returned to Elam.[33]

Following his victory over the Elamites, Ashurbanipal had to deal with a series of revolts within his own borders. Bel-iqisha, chieftain of the Gambulians (an Aramean tribe) in Babylonia, rebelled after he had been implicated as supporting the Elamite invasion and had been forced to relinquish some of his authority. Little is known of this revolt, but there is a letter preserved in which Ashurbanipal orders the governor of Uruk, Nabu-ushabshi, to attack Bel-iqisha. Nabu-ushabshi apparently claimed that Bel-iqisha was solely to blame for the Elamite invasion.[34] Bel-iqisha's revolt does not appear to have caused much damage and he was killed shortly after revolting by a boar. Shortly thereafter in 663 BC, Bel-iqisha's son Dunanu surrendered to Ashurbanipal.[24]

Shamash-shum-ukin appears to have tired of Ashurbanipal's rule by 653 BC; inscriptions from Babylon suggest that Ashurbanipal had been managing the affairs of Shamash-shum-ukin and had been essentially dictating his decrees. Shamash-shum-ukin sent diplomats to Teumann in Elam, hoping to use his army to destabilize Ashurbanipal's rule. Ashurbanipal appears to have been unaware of Shamash-shum-ukin's involvement, though he successfully defeated the Elamites in 653 BC and ravaged their cities and country.[4] The final battle in this campaign, the Battle of Ulai, took place near the Elamite capital of Susa and was a decisive Assyrian victory, partly due to defections in the Elamite army. King Teumann was killed in the battle, as was one of his vassals called Shutruk-Nahhunte, the king of the city Hidalu. In the aftermath of his victory, Ashurbanipal installed two of Urtak's sons as rulers, proclaiming Ummanigash as king at Madaktu and Susa and Tammaritu I as king at Hidalu.[33] In his inscriptions, Ashurbanipal describes his victory as follows:

Like the onset of a terrible hurricane I overwhelmed Elam in its entirety. I cut off the head of Teumann, their king, – the haughty one, who plotted evil. Countless of his warriors I slew. Alive, with my hands, I seized his fighters. With their corpses I filled the plain about Susa as with baltu and ashagu[n 1]. Their blood I let run down the Ulai; its water I dyed red like wool.[35]

Dunanu, who had joined the Elamites in the war, was captured alongside his family and executed and the Gambulians were attacked by Ashurbanipal's army and brutally punished, with their capital of Shapibel being flooded and many of its inhabitants slaughtered. In Dananu's stead, Ashurbanipal appointed a noble called Rimutu as the new Gambulian chieftain after he had agreed to pay a considerable sum in tribute to the Assyrian king.[24] Ashurbanipal described his vengeance against Dananu with these words:

On my return march I set my face against Dunanu, (king) of Gambulu, who had put his faith in Elam. Shapibel, the stronghold of Gambulu, I captured. I entered that city; its inhabitants I slaughtered like lambs. Dunanu and Sam'gunu, who had made difficult for me the exercising of sovereignty, – in shackles, fetters of iron, bonds of iron, I bound them hand and foot. The rest of the sons of Bel-iqisha, his family, the seed of his father's house, all there were, Nabû-nâ'id, Bêl-êtir, sons of Nabû-shum-êresh, the proconsul, and the bones of the father who begot them, together with Urbi and Tebê, peoples of Gambulu, cattle, sheep, asses, horses, mules, I carried off from Gambulu to Assyria. Shapibel, his stronghold, I devastated, I destroyed, I laid waste to by flooding it.[36]

Dealings with Lydia and the Cimmerians

The Cimmerians, a nomadic Indo-European people living in the southern Caucasus north of Assyria, had invaded Assyria during the reign of Ashurbanipal's father. After Esarhaddon defeated them, the Cimmerians had turned to attack the Lydian kingdom in western Anatolia, ruled by the king Gyges. After allegedly receiving advice from Assyria's god, Assur, in a dream, Gyges sent his diplomats to ask Ashurbanipal for assistance. The Assyrians did not even know that Lydia existed and after the two states successfully established communication with the help of interpreters, the Cimmerian invasion of Lydia was defeated in c. 665 BC, with two Cimmerian chiefs being imprisoned in Nineveh and large amounts of spoils being secured by Ashurbanipal's forces. The extent to which the Assyrian army was involved in the Lydian campaign is unknown, but it appears that Gyges was disappointed with the help as he just twelve years later broke his alliance with Ashurbanipal, allying with Psamtik I of Egypt instead. After this, Ashurbanipal cursed Gyges and when Lydia was overrun by its enemies c. 652–650 BC there was much rejoicing in Assyria.[37]

While the Assyrian forces were on campaign in Elam, an alliance of Persians, Cimmerians and Medes marched on the capital Nineveh and managed to reach the city's walls. To counteract this threat, Ashurbanipal called on his Scythian allies and successfully defeated the enemy army. The Median king, Phraortes, is generally held to have been killed in the fighting.[4] This attack is poorly documented and it is possible that Phraortes wasn't present at all and his unfortunate death instead belongs to a Median campaign during the reign of one of Ashurbanipal's successors.[37]

After his death c. 652 BC, Gyges was succeeded by his son Ardys. Because the Scythians had driven the Cimmerians from their homes, the Cimmerians invaded Lydia again and successfully captured most of the kingdom. As his father had before him, Ardys also sent for aid from Ashurbanipal, stating that "You cursed my father and bad luck befell him; but bless me, your humble servant, and I will carry your yoke". It is unknown if any Assyrian aid arrived, but Lydia was successfully freed from the Cimmerians. They would not be driven out of Lydia completely until the reign of Ardys's grandson Alyattes.[37]

Revolt of Shamash-shum-ukin in Babylon

By the 650s BC, the hostility between Shamash-shum-ukin and Ashurbanipal would have been apparent to their vassals. A letter from Zakir, a courtier at Shamash-shum-ukin's court, to Ashurbanipal described how visitors from the Sea Land had publicly criticized Ashurbanipal in front of Shamash-shum-ukin, using the phrase "this is not the word of a king!". Zakir reported that though Shamash-shum-ukin was angered, he and his governor of Babylon, Ubaru, chose to not take action against the visitors.[39] Perhaps the most important factors behind Shamash-shum-ukin's revolt was his dissatisfaction with his position relative to that of his brother, the constant resentment of Assyria in general by the Babylonians and the constant willingness of the ruler of Elam to join anyone who waged war against Assyria.[40]

Shamash-shum-ukin rebelled against Ashurbanipal in 652 BC. This civil war would last for three years.[6] Inscription evidence suggests that Shamash-shum-ukin addressed the citizens of Babylon to join him in his revolt. In Ashurbanipal's inscriptions, Shamash-shum-ukin is quoted to have said "Ashurbanipal will cover with shame the name of the Babylonians", which Ashurbanipal refers to as "wind" and "lies". Soon after Shamash-shum-ukin began his revolt, the rest of southern Mesopotamia rose up against Ashurbanipal alongside him.[41] The beginning of Ashurbanipal's inscriptions regarding Shamash-shum-ukin read as follows:

In these days Shamash-shum-ukin, the faithless brother of mine, whom I had treated well and had set up as king of Babylon, – every imaginable thing that kingship calls for, I made and gave him; soldiers, horses, chariots, I equipped and put into his hands; cities, fields, plantations, together with the people who live therein, I gave him in larger numbers than my father had ordered. But he forgot this kindness I had shown him and planned evil. Outwardly, with his lips, he was speaking fair words while inwardly his heart was designing murder. The Babylonians, who had been loyal to Assyria and faithful vassals of mine, he deceived, speaking lies to them.[42]

According to the inscriptions of Ashurbanipal, Shamash-shum-ukin was very successful in finding allies against the Assyrians. Ashurbanipal identifies three groups that aided his brother, first and foremost there were the Chaldeans, Arameans and the other peoples of Babylonia, then there were the Elamites and lastly the kings of Gutium, Amurru and Meluhha. This last group of kings might refer to the Medes (as Gutium, Amurru and Meluhha no longer existed at this point) but this is uncertain. Meluhha might have referred to Egypt, which did not aid Shamash-shum-ukin in the war. Shamash-shum-ukin's ambassadors to the Elamites had offered gifts (called "bribes" by Ashurbanipal) and their king, Ummanigash, sent an army under the command of Undashe, the son of King Teumman, to aid in the conflict.[43]

Despite the seemingly strong alliance of Assyrian enemies, Shamash-shum-ukin's situation looked grim by 650 BC, with Ashubanipal's forces having besieged Sippar, Borsippa, Kutha and Babylon itself. Having endured starvation and disease over the course of the siege, Babylon finally fell in 648 BC and was plundered by Ashurbanipal. Shamash-shum-ukin is traditionally believed to have committed suicide by setting himself and his family on fire in his palace,[44][6] but contemporary texts only say that he "met a cruel death" and that the gods "consigned him to a fire and destroyed his life". In addition to suicide though self-immolation or other means, it is possible that he was executed, died accidentally or was killed in some other way.[45] Ashurbanipal describes his victory and his vengeance against those that had supported Shamash-shum-ukin in his inscriptions as follows:

Assur, Sin, Shamash, Adad, Bêl, Nabû, Ishtar of Nineveh, the queen of Kidmuri, Ishtar of Arbela, Urta, Nergal and Nusku, who march before me, slaying my foes, cast Shamash-shum-ukin, my hostile brother, who became my enemy, into the burning flames of a conflagration and destroyed him. As for the people who hatched these plans for Shamash-shum-ukin, my hostile brother, and did the evil, but who were afraid of death and valued their lives highly, they did not cast themselves into the fire with Shamash-shum-ukin, their lord. Those of them who fled before the murderous iron dagger, famine, want and flaming fire, and found a refuge, – the net of the great gods, my lords, which cannot be eluded, brought them low. Not one escaped; not one sinner slipped through my hands, of those whom the gods had counted for my hands.

The chariots, coaches, palanquins, his concubines, the goods of his palace, they brought before me. As for those men and their vulgar mouths, who uttered vulgarity against Assur, my god, and plotted evil against me, the prince who fears him, – I slit their tongues and brought them low. The rest of the people, alive, by the colossi, between which they had cut down Sennacherib, the father of the father who begot me, – at that time, I cut down those people there, as an offering to his shade. Their dismembered bodies I fed to the dogs, swine, wolves and eagles, to the birds of heaven and the fish of the deep.[46]

After Shamash-shum-ukin's defeat, Ashurbanipal appointed a new governor of the city, Kandalanu, possibly one of his younger brothers. Kandalanu's realm was the same as Shamash-shum-ukin's with the exception of the city of Nippur, which Ashurbanipal converted into a powerful Assyrian fortress.[6] The authority of Kandalanu is likely to have been very limited and few records survive of his reign at Babylon. If he wasn't one of Ashurbanipal's brothers, he was likely a Babylonian noble who had allied with Ashurbanipal in the civil war and had been rewarded with the rank of king. Kandalanu probably lacked any true political and military power, which was instead firmly in the hands of the Assyrians.[47]

Second Elamite campaign

The Elamites under Ummanigash had joined Shamash-shum-ukin in the war, partly to restore control over the parts of Elam that Ashurbanipal had incorporated into the Assyrian Empire. Ummanigash's army was defeated near the city Der and as a result, he was deposed in Elam by Tammaritu II, who then ruled as king. Ummanigash fled to the Assyrian court and was granted asylum by Ashurbanipal. Tammaritu II's rule was brief and despite success in some battles alongside the Chaldean warlord Nabu-bel-shumati, he was deposed in another revolt in 649 BC. The new king, Indabibi, had an extremely brief reign and was murdered after Ashurbanipal threatened to invade Elam again because of Elam's role in supporting his enemies.[49]

In Indibibi's stead, Humban-haltash III became king in Elam. Nabu-bel-shumati continued fighting against Ashurbanipal from outposts within Elam and though Humban-haltash was in favor of giving up the Chaldean rebel, Nabu-bel-shumati had too many supporters in Elam in order for this to go through. As such, Ashurbanipal invaded Elam again in 647 BC and after his short-lived resistance failed, Humban-haltash abandoned his seat at Madaktu and fled into the mountains.[49] Humban-haltash was briefly replaced as king by Tammaritu II, who regained his throne. After the Assyrians had plundered the region of Khuzistan the Assyrian army returned home and Humban-haltash returned and retook the throne.[50]

Ashurbanipal returned to Elam in 646 BC and Humban-haltash again abandoned Madaktu, fleeing first to the city Dur-Untash and then into the mountains in eastern Elam. Ashurbanipal's forces pursued Humban-haltash, plundering and razing cities on their way. All major political centers in Elam were crushed and nearby chiefdoms and petty kingdoms who had previously paid tribute to the Elamite king began paying tribute to Ashurbanipal instead. Among these kingdoms was Parsua, possibly a predecessor of the empire that would be founded by the Achaemenids a century later.[50] Parsua's king, Cyrus (possibly the same person as Cyrus I, the grandfather of Cyrus the Great), had originally sided with the Elamites at the beginning of the campaign, and had thus been forced to supply his son Arukku as a hostage. Countries which had never previously had contact with the Assyrians, such as a kingdom ruled by a king called Ḫudimiri which "extended beyond Elam", also began paying tribute to the Assyrians for the first time.[37]

On their way back from their campaign, the Assyrian forces brutally plundered Susa. In Ashurbanipal's triumphant inscriptions detailing the sack it is described in great detail, recounting how the Assyrians desecrated the royal tombs, looted and razed temples, stole the statues of the Elamite gods and sowed salt in the ground. The detail and length of these inscriptions suggest that the event was meant to shock the world through its proclamation of the defeat and eradication of the Elamites as a distinct cultural entity.[50] Translated into English, a part of Ashurbanipal's inscription of the sack reads:

"Susa, the great holy city, abode of their gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed... I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones toward the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt."[4]

Despite the thorough and brutal campaign, the Elamites endured as a political entity for some time. Humban-haltash returned to rule at Madaktu and (belatedly) sent Nabu-bel-shumati to Ashurbanipal, though the Chaldean committed suicide on his way to Nineveh. After Humban-haltash was deposed, captured and sent to the Assyrians in a revolt shortly thereafter, Assyrian records cease to speak of Elam.[52] Ashurbanipal appointed no new governors of the Elamite cities after his campaign and made no attempts to integrate the country as an Assyrian province, instead leaving it open and undefended. The fields were left empty and barren. In the decades following the campaign, the Persians would migrate into the region and rebuild the devastated cities.[4]

Arabian campaigns

Ashurbanipal's war against tribes in the Arabian Peninsula has received relatively little attention from modern historians but is the campaign with the longest account in his own writings. The chronology of these campaigns is uncertain and based on the series of annals Ashurbanipal wrote, although the narrative appears to have been slightly altered over the course of a few years. Ashurbanipal's earliest account of his campaign against the Arabs was created in 649 BC and describes how the king Yauta, son of Hazael, king of the Qedarites (who had been a tributary of Ashurbanipal's father) revolted against Ashurbanipal, together with another Arabic king called Ammuladdin, and plundered the western lands of the Assyrian Empire. According to Ashurbanipal's account, his army, together with the army of King Kamas-halta of Moab, defeated the rebel forces. Ammuladdin was captured and sent in chains to Assyria and Yauta escaped. In the place of Yauta a loyal Arabian warlord called Abiyate was granted kingship of the Qedarites. This early narrative of the campaign is different from most of Ashurbanipal's other military accounts in that the phrase "in my nth campaign" is missing, the king is not described as defeating the enemy in person and the enemy king survives and flees rather than being captured and executed.[54]

The second version of the narrative, composed in 648 BC, also includes that Ashurbanipal defeated Adiya, a queen of the Arabs, and that Yauta fled to another chieftain, Natnu of the Nabayyate, who refused him and remained loyal to Ashurbanipal. Even later versions of the narrative also include mentions of how Yauta also had revolted against Esarhaddon, years prior. These later accounts also explicitly connect Yauta's rebellion to the revolt of Shamash-shum-ukin, placing it at the same time and suggesting that the western raids by the Arabs were prompted by the instability caused by the Assyrian civil war.[55]

Sometime after the conclusion of this first brief conflict, Ashurbanipal conducted a second campaign against the Arabs. Ashurbanipal's account of this conflict largely concerns the movements of his army through Syria in search of Uiate (conflated with Yauta but possibly a different person) and his Arabian soldiers. According to the account, the Assyrian army marched from Syria to Damascus and then on to Hulhuliti, after which they captured Abiyate and defeated Uššo and Akko. There is no mention of the reason behind Abiyate's rebellion. Furthermore, the Nabayyate, who had aided Ashurbanipal in the previous campaign, are mentioned as being defeated in his second war against the Arabs, without any further information on what had led to the change in their relationship between the two campaigns.[57]

The latest version of the Arabian narrative specifies the two campaigns as composing Ashurbanipal's ninth campaign and further expands upon its contents. In this version, it is specified that the Abiyate who replaced Yauta as king of the Qedarites and the king Ammuladdin had been the chief Arabian generals joining Shamash-shum-ukin's war and that spoils brought back to Assyria from the campaigns caused inflation in Ashurbanipal's empire and famine in Arabia. It is also made clear that Ashurbanipal himself, not just his army, had been personally victorious in the conflict. This later version also states that Uiate was captured and paraded in Nineveh together with prisoners captured during the wars in Elam.[58]

Succession and chronology

.jpg.webp)

The end of Ashurbanipal's reign and the beginning of the reign of his successor, Ashur-etil-ilani, is shrouded in mystery on account of a lack of available sources. The annals kept by Ashurbanipal, the main sources to his reign, end in 636 BC, possibly because the king was ill. Inscriptions by Ashur-etil-ilani suggest that his father died a natural death, but do not shed light on when exactly this happened.[59] Before archaeological excavations and discoveries in the 1800s, Ashurbanipal was known by the name Sardanapalus (Ancient Greek: Σαρδανάπαλος, romanized: Sardanápalos), based on the writings of the ancient Greeks, and had been misidentified as the last king of Assyria. One popular story of his end was that Sardanapalus had burnt himself, his concubines and servants alive, along with his entire palace at the Fall of Nineveh in 612 BC (almost twenty years after the actual Ashurbanipal died).[3]

Although Ashurbanipal's final year is often repeated as 627 BC,[9][4] this follows an inscription at Harran made by the mother of the Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus nearly a century later. The final contemporary evidence for Ashurbanipal being alive and reigning as king is a contract from the city of Nippur made in 631 BC.[60] To get the attested lengths of the reigns of his successors to match, it is generally agreed that Ashurbanipal either died, abdicated or was deposed in 631 BC.[61] 631 BC is typically used as the year of his death.[6] If Ashurbanipal's reign had ended in 627 BC, the inscriptions of his successors Ashur-etil-ilani and Sinsharishkun in Babylon would have been impossible, as the city was seized by Nabopolassar in 626 BC, and never again fell into Assyrian hands.[62]

One possible way to justify a 42-year reign of Ashurbanipal is by assuming there was a coregency between him and Ashur-etil-ilani, but there had never been a coregency in prior Assyrian history and the idea is explicitly contradicted by Ashur-etil-ilani's own inscriptions which describe him as ascending to the throne after the end of his father's reign. It is possible that the 42-year error came about in later Mesopotamian historiography on account of the knowledge that Ashurbanipal ruled concurrently with Babylonian rulers Shamash-shum-ukin and Kandalanu, whose reigns together amount to 42 years, but Kandalanu survived Ashurbanipal by three years, dying in 627 BC.[63]

Another once popular idea, for instance defended by Polish historian Stefan Zawadski in his book The Fall of Assyria (1988), is that Ashubanipal and Kandalanu were the same person, "Kandalanu" simply being the name the king used in Babylon. This is considered unlikely for several reasons. No previous Assyrian king is known to have used an alternate name in Babylon. Inscriptions from Babylonia also show a difference in the lengths of the reigns of Ashurbanipal and Kandalanu; Ashurbanipal's reign is counted from his first full year as king (668 BC) and Kandalanu's is counted from his first full year as king (647 BC). All Assyrian kings who personally ruled Babylon used the title "King of Babylon" in their own inscriptions, but it is not used in Ashurbanipal's inscriptions, even those made after 648 BC. Most importantly, Babylonian documents treat Ashurbanipal and Kandalanu as two different people. No contemporary Babylonian sources describe Ashurbanipal as King of Babylon.[66]

Ashurbanipal was succeeded as king by his son, Ashur-etil-ilani, and he seems to have been inspired by the succession plans of his father as another of his sons, Sinsharishkun, was granted the fortress-city of Nippur and was designated to be the successor of Kandalanu at Babylon once Kandalanu died.[6]

Family and children

The name of Ashurbanipal's queen was Libbali-sharrat[69] (Akkadian: Libbali-šarrat[70]). Not much is known of Libbali-sharrat, but she was already married to Ashurbanipal when he became king and might have married him as early as 673 BC, at around the time of the death of Esarhaddon's queen Esharra-hammat.[71]

Three of Ashurbanipal's children are known by name:

- Ashur-etil-ilani (Akkadian: Aššur-etil-ilāni)[72] – son who ruled as king of Assyria 631–627 BC.[2]

- Sinsharishkun (Akkadian: Sîn-šar-iškun)[73] – son who ruled as king of Assyria 627–612 BC.[2]

- Ninurta-sharru-usur (Akkadian: Ninurta-šarru-uṣur)[74] – son born of a lower wife (i.e., not Libbali-sharrat), seems to have played no political role.[74]

The inscriptions of Sinsharishkun which mention him being selected for the kingship "from among his equals" (i.e., brothers) suggests that Ashurbanipal had more sons in addition to Ashur-etil-ilani, Sinsharishkun and Ninurta-sharru-usur.[75]

It is possible that Ashurbanipal's lineage returned to power in Mesopotamia after the fall of Assyria in 612–609 BC. The mother of the last of the Neo-Babylonian kings, Nabonidus (r. 556–539 BC), was from Harran and had Assyrian ancestry. This woman, Addagoppe, was according to her own inscriptions born in the 20th year of Ashurbanipal's reign (648 BC, as years were counted from the king's first full year). British scholar Stephanie Dalley considers it "almost certain" that Addagoppe was a daughter of Ashurbanipal on account of her own inscriptions claiming that Nabonidus was of Ashurbanipal's dynastic line.[76] American Professor of Biblical Studies Michael B. Dick has refuted this, pointing out that even though Nabonidus did go to some length to revive some old Assyrian symbols (such as wearing a wrapped cloak in his depictions, absent in those of other Neo-Babylonian kings but present in Assyrian art) and attempted to link himself to the Sargonid dynasty, there is "no evidence whatsoever that Nabonidus was related to the Sargonid Dynasty".[77]

Legacy

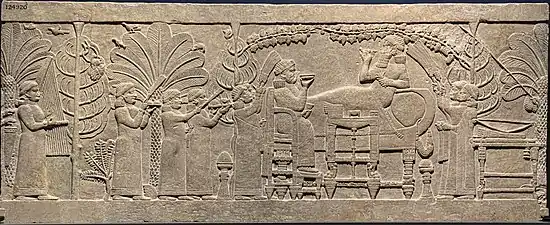

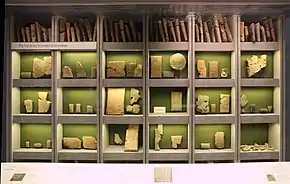

Library of Ashurbanipal

The Library of Ashurbanipal was the first systematically organized library in the world.[3][9] The library is the best known of Ashurbanipal's accomplishments and the king himself considered it his greatest.[4] The library was assembled at Ashurbanipal's command, with scribes being sent out throughout his empire to collect and copy texts of every type and genre from the libraries of the temples. Most of the collected texts were observations of events and omens, texts detailing the behaviour of certain men and of animals, texts on the movements of celestial objects and so forth. Present in the library were also dictionaries for Sumerian, Akkadian and other languages and many religious texts, such as rituals, fables, prayers and incantations.[9]

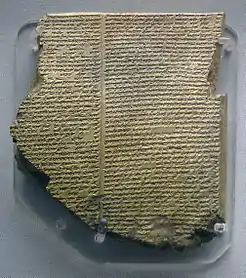

Most of the traditional Mesopotamian stories and tales known today, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Enûma Eliš (the Babylonian creation myth), Erra, the Myth of Etana and the Epic of Anzu, only survived until the modern era because they were included in Ashurbanipal's library. The library covered the entire spectrum of Ashurbanipal's literary interests and also included folk tales (such as The Poor Man of Nippur, a predecessor of one of the tales in One Thousand and One Nights), handbooks and scientific texts.[9]

Ashurbanipal described the reasoning behind collecting such a vast library, amounting to over 30,000 clay tablets,[4] with these words:

I, Ashurbanipal, king of the universe, on whom the gods have bestowed intelligence, who has acquired penetrating acumen for the most recondite details of scholarly erudition (none of my predecessors having any comprehension of such matters), I have placed these tablets for the future in the library at Nineveh for my life and for the well-being of my soul, to sustain the foundations of my royal name.[4]

Nineveh was destroyed in 612 BC and the Library of Ashurbanipal was buried under the walls of Ashurbanipal's burning palace and lost to history for more than two thousand years. It was unearthed in the 19th century by Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam and the translations of the contents within it by George Smith brought the ancient Mesopotamian texts to the modern world. Prior to its discovery, there was a widespread notion that the Bible was the oldest book and a work without precedent, an idea which was decisively disproven with the discovery of the library.[4]

Assessment by historians

At the time of Ashurbanipal's reign, the Neo-Assyrian Empire was the largest empire the world had ever seen and its capital, Nineveh, at about 120,000 citizens,[78] was probably the largest city on the planet.[3] During his reign, the Assyrian Empire prospered economically, despite its continuing expansion.[9] He is often regarded as the last great king of Assyria[9][13][4] and is recognized, alongside his two predecessors Esarhaddon and Sennacherib, as one of the greatest Assyrian kings.[79]

Ashurbanipal has sometimes been characterized as a zealot. The king rebuilt, repaired and expanded a majority of the major shrines throughout his empire and many of the actions he took during his reign were due to omen reports, something he was very interested in.[9] He appointed two of his younger brothers, Ashur-mukin-paleya and Ashur-etel-shame-erseti-muballissu, as priests in the cities Assur and Harran respectively.[80] He has also been seen as a patron of the arts due to the many sculptures and reliefs he erected in his palaces at Nineveh, depicting the most important events from his long reign. The style used in these works of art has an "epic quality" unlike the artwork produced under his predecessors.[9]

Assessment of Ashurbanipal has not solely been positive. In 639 BC, Ashurbanipal named the year (years were generally named after people in ancient Assyria, often military officials) after his chief musician, Bulluṭu, which Assyriologist Julian E. Reade saw as the move of an "irresponsible and self-indulgent" king.[61] Though Assyria reached the apex of its power under Ashurbanipal's rule, the empire collapsed quickly after his death. Whether Ashurbanipal is partly to blame for Assyria's downfall is disputed. J. A. Delaunay, author of the Encyclopaedia Iranica entry on the king writes that the Neo-Assyrian Empire under Ashurbanipal had already began "exhibiting clear symptoms of impending dislocation and fall",[13] while Donald John Wiseman, in the Encyclopaedia Britannica article on the king, holds that "It is no indictment of his rule that his empire fell within two decades after his death; this was due to external pressures rather than to internal strife".[9]

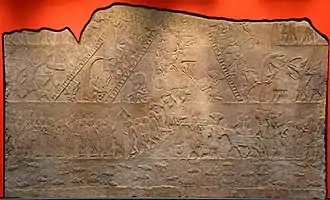

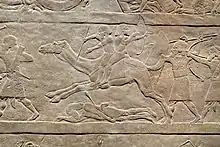

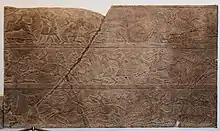

In art and popular culture

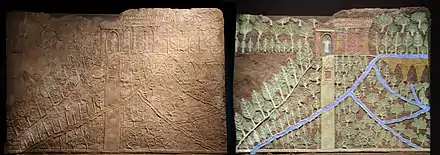

Depictions of Ashurbanipal in artwork survive from his reign. The Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal, a set of Assyrian palace reliefs from Ashurbanipal's palace, can be seen at the British Museum in London. These reliefs depict the king hunting and killing Mesopotamian lions.[81] The Assyrian king was tasked with protecting his own people, often being referred to as a "shepherd". This protection included defending against external enemies and defending citizens from dangerous wild animals. To the Assyrians, the most dangerous animal of all was the lion, used (similarly to foreign powers) as an example of chaos and disorder due to their aggressive nature. To prove themselves worthy of rule and illustrate that they were competent protectors, Assyrian kings engaged in ritual lion hunts. Lion-hunting was reserved for Assyrian royalty and was a public event, staged at parks in or near the Assyrian cities.[82]

Ashurbanipal has also been the subject of artwork created in modern times. In 1958, surrealist painter Leonora Carrington painted Assurbanipal Abluting Harpies, an oil on canvas at the Israel Museum depicting Ashurbanipal pouring a white substance onto the heads of pigeon-like creatures with human faces.[83] A statue of the king, called Ashurbanipal, was created by sculptor Fred Parhad in 1988 and placed on a street near the San Francisco City Hall. The statue cost $100,000 and was described as the "first sizable bronze statue of Ashurbanipal". It was presented to the City of San Francisco as a gift from the Assyrian people on May 29, 1988, Parhad being of Assyrian descent. Some local Assyrians expressed fears that the statue resembled the legendary Mesopotamian hero Gilgamesh more than it resembled the actual Ashurbanipal. Parhad defended the statue as representing Ashurbanipal, though explained that he had taken some artistic liberties.[84]

Ashurbanipal has also made occasional appearances in popular culture in various media. Robert E. Howard wrote a short story entitled The Fire of Asshurbanipal, first published in the December 1936 issue of Weird Tales magazine, about an "accursed jewel belonging to a king of long ago, whom the Grecians called Sardanapalus and the Semitic peoples Asshurbanipal".[10] "The Mesopotamians", a 2007 song by They Might Be Giants, mentions Ashurbanipal alongside Gilgamesh, Sargon, and Hammurabi.[85] Ashurbanipal was used as the ruler of the Assyrians in the game Civilization V.[86]

Titles

In an inscription on a cylinder dated to 648 BC,[87] Ashurbanipal uses the following titles:

I am Ashurbanipal, the great king, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, king of the four regions of the world; offspring of the loins of Esarhaddon, king of the universe, king of Assyria, viceroy of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad; grandson of Sennacherib, king of the universe, king of Assyria.[87]

A similar titulature is used on one of Ashurbanipal's many tablets:

I, Ashurbanipal, the great king, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, king of the four regions of the world, son of Esarhaddon, king of the universe, king of Assyria, grandson of Sennacherib, king of the universe, king of Assyria, eternal seed of royalty ...[88]

A longer variant is presented on one of Ashurbanipal's building inscriptions in Babylon:

Ashurbanipal, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, king of the four regions of the world, king of kings, unrivaled prince, who, from the Upper to the Lower Sea, holds sway and has brought in submission at his feet all rulers; son of Esarhaddon, the great king, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, viceroy of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad; grandson of Sennacherib, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, am I.[89]

Notes

- Baltu and ashagu were probably varieties of thorny shrub.

References

- Lipschits 2005, p. 13.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 243.

- British Museum.

- Mark 2009.

- Finkel 2013, p. 123.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 8.

- Novotny & Singletary 2009, pp. 174–176.

- Ahmed 2018, pp. 65–66.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Price 2001, pp. 99–118.

- Akkadian: 𒀭𒊹𒆕𒀀 An-shar-du-a in "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu. Assyrian pronunciation in Quentin, A. (1895). "Inscription Inédite du Roi Assurbanipal: Copiée Au Musée Britannique le 24 Avril 1886". Revue Biblique (1892-1940). 4 (4): 554. ISSN 1240-3032. JSTOR 44100170.

- Miller & Shipp 1996, p. 46.

- Delaunay 1987, pp. 805-806.

- In Akkadian 𒀭𒊹 is god Anshar, 𒆕𒀀 means "newborn young" . In Assyrian, the prononciation used is bāni-apli, bāni meaning "to create", "to give" , and applu/apli meaning "the heir", "the eldest son"

- "Stela British Museum". The British Museum.

- Novotny & Singletary 2009, p. 168.

- Novotny & Singletary 2009, pp. 168–173.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 63.

- Novotny & Singletary 2009, p. 170.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 64.

- Radner 2003, p. 170.

- Zaia 2019, p. 20.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 68.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 80.

- Mark 2014.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- Radner 2003, pp. 176–177.

- Pritchard, James B. (2016). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament with Supplement. Princeton University Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-4008-8276-2.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- Maspero, G. (Gaston); Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry); McClure, M. L. (1903). History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia and Assyria. London : Grolier Society.

- Maspero, G. (Gaston); Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry); McClure, M. L. (1903). History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia and Assyria. London : Grolier Society. p. 427.

- Carter & Stolper 1984, p. 50.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 79.

- Luckenbill 1927, pp. 299–300.

- Luckenbill 1927, p. 300.

- Delaunay 1987, pp. 805–806.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 88.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 90.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 91.

- Luckenbill 1927, p. 301.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 93.

- Johns 1913, pp. 124–125.

- Zaia 2019, p. 21.

- Luckenbill 1927, pp. 303–304.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 254.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- Carter & Stolper 1984, p. 51.

- Carter & Stolper 1984, p. 52.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- Carter & Stolper 1984, pp. 52–53.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- Gerardi 1992, pp. 67–74.

- Gerardi 1992, pp. 79–81.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- Gerardi 1992, pp. 83–86.

- Gerardi 1992, pp. 89–94.

- Ahmed 2018, p. 121.

- Reade 1970, p. 1.

- Reade 1998, p. 263.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 246.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 250.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- British Museum notice in 2018 temporary exhibit "I am Ashurbanipal king of the world, king of Assyria"

- Na’aman 1991, pp. 251–252.

- "Wall panel; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- Notices from the British Museum

- Collins 2004, p. 1.

- Kertai 2013, p. 118.

- Kertai 2013, p. 119.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 248.

- Tallqvist 1914, p. 201.

- Frahm 1999, p. 322.

- Na’aman 1991, p. 255.

- Dalley 2003, p. 177.

- Dick 2004, p. 15.

- Chandler & Fox 2013, p. 362.

- Budge 1880, p. xii.

- Novotny & Singletary 2009, p. 171.

- Ashrafian 2011, pp. 47–49.

- Introducing the Assyrians.

- Assurbanipal Abluting Harpies.

- Fernandez 1987.

- Nardo 2012, p. 88.

- Pitts 2013.

- Luckenbill 1927, p. 323.

- Luckenbill 1927, p. 356.

- Luckenbill 1927, p. 369.

Cited bibliography

- Ahmed, Sami Said (2018). Southern Mesopotamia in the time of Ashurbanipal. The Hague: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3111033587.

- Ashrafian, H. (2011). "An extinct Mesopotamian lion subspecies". Veterinary Heritage. 34 (2): 47–49.

- Budge, Ernest A. (2007) [1880]. The History of Esarhaddon. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 978-1136373213.

- Carter, Elizabeth; Stolper, Matthew W. (1984). Elam: Surveys of Political History and Archaeology. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520099500.

- Chandler, Tertius; Fox, Gerald (2013) [1974]. 3000 Years of Urban Growth. New York: Elsevier. ISBN 978-1483248899.

- Collins, Paul (2004). "The Symbolic Landscape of Ashurbanipal". Notes in the History of Art. 23 (3): 1–6. doi:10.1086/sou.23.3.23206845. S2CID 192520014.

- Dalley, Stephanie (2003). "The Hanging Gardens of Babylon?". Herodotus and His World: Essays from a Conference in Memory of George Forrest. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199253746.

- Delaunay, J. A. (1987). "AŠŠURBANIPAL". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 8. pp. 805–806.

- Dick, Michael B. (2004). ""David's Rise to Power" and the Neo-Babylonian Succession Apologies". David and Zion: Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060927.

- Finkel, Irving (2013). The Cyrus Cylinder: The Great Persian Edict from Babylon. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1780760636.

- Frahm, Eckhart (1999). "Kabale und Liebe: Die königliche Familie am Hof zu Ninive". Von Babylon bis Jerusalem: Die Welt der altorientalischen Königsstädte. Reiss-Museum Mannheim.

- Gerardi, Pamela (1992). "The Arab Campaigns of Aššurbanipal: Scribal Reconstruction of the Past" (PDF). State Archives of Assyria Bulletin. 6 (2): 67–103.

- Johns, C. H. W. (1913). Ancient Babylonia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 124. OCLC 1027304.

Shamash-shum-ukin.

- Kertai, David (2013). "The Queens of the Neo-Assyrian Empire". Altorientalische Forschungen. 40 (1): 108–124. doi:10.1524/aof.2013.0006. S2CID 163392326.

- Lipschits, Oled (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah under Babylonian Rule. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060958.

- Luckenbill, Daniel David (1927). Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume 2: Historical Records of Assyria From Sargon to the End. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 926853184.

- Miller, Douglas B.; Shipp, R. Mark (1996) [1886]. An Akkadian Handbook: Paradigms, Helps, Glossary, Logograms, and Sign List. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-0931464867.

- Na’aman, Nadav (1991). "Chronology and History in the Late Assyrian Empire (631–619 B.C.)". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie. 81 (1–2): 243–267. doi:10.1515/zava.1991.81.1-2.243. S2CID 159785150.

- Nardo, Don (2012). Babylonian Mythology. Greenhaven Publishing. ASIN B00MMP7YC8.

- Novotny, Jamie; Singletary, Jennifer (2009). "Family Ties: Assurbanipal's Family Revisited". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 106: 167–177.

- Price, Robert M. (2001). Nameless Cults: The Cthulhu Mythos Fiction of Robert E. Howard. Ann Arbor: Chaosium. ISBN 978-1568821306.

- Radner, Karen (2003). "The Trials of Esarhaddon: The Conspiracy of 670 BC". ISIMU: Revista sobre Oriente Próximo y Egipto en la antigüedad. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. 6: 165–183.

- Reade, J. E. (1970). "The Accession of Sinsharishkun". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 23 (1): 1–9. doi:10.2307/1359277. JSTOR 1359277. S2CID 159764447.

- Reade, J. E. (1998). "Assyrian eponyms, kings and pretenders, 648–605 BC". Orientalia (NOVA Series). 67 (2): 255–265. JSTOR 43076393.

- Tallqvist, Knut Leonard (1914). Assyrian Personal Names (PDF). Leipzig: August Pries. OCLC 6057301.

- Zaia, Shana (2019). "My Brother's Keeper: Assurbanipal versus Šamaš-šuma-ukīn" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History. 6 (1): 19–52. doi:10.1515/janeh-2018-2001. S2CID 165318561.

Cited web sources

- "Ashurbanipal". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Assurbanipal Abluting Harpies". The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2009). "Ashurbanipal". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2014). "Esarhaddon". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Introducing the Assyrians". The British Museum. 2018-06-19. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- "Who was Ashurbanipal?". The British Museum. 2018-06-19. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

Cited news sources

- Fernandez, Elizabeth (31 December 1987). "Statue of Assyrian king in skirt stirs controversy". The Telegraph. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- Pitts, Russ (27 June 2013). "Knowing history: Behind Civ 5's Brave New World". Polygon. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashurbanipal. |

- Daniel David Luckenbill's Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume 2: Historical Records of Assyria From Sargon to the End, containing translations of a large number of Ashurbanipal's inscriptions.

Ashurbanipal Born: 685 BC Died: 631 BC | ||

| Preceded by Esarhaddon |

King of Assyria 669–631 BC |

Succeeded by Ashur-etil-ilani |