Sussex in the High Middle Ages

Sussex in the High Middle Ages includes the history of Sussex from the Norman Conquest in 1066 until the death of King John, considered by some to be the last of the Angevin kings of England, in 1216. It was during the Norman period that Sussex achieved its greatest importance in comparison with other English counties.[1] Throughout the High Middle Ages, Sussex was on the main route between England and Normandy, and the lands of the Anglo-Norman nobility in what is now western France. The growth in Sussex's population, the importance of its ports and the increased colonisation of the Weald were all part of changes as significant to Sussex as those brought by the neolithic period, by the Romans and the Saxons.[2] Sussex also experienced the most radical and thorough reorganisation of land in England, as the Normans divided the county into five (later six) tracts of lands called rapes. Although Sussex may have been divided into rapes earlier in its history,[3] under the Normans they were clearly administrative and fiscal units.[4] Before the Norman Conquest Sussex had the greatest concentration of lands belonging to the family of Earl Godwin. To protect against rebellion or invasion, the scattered Saxon estates in Sussex were consolidated into the rapes as part of William the Conqueror's 'Channel march'.[5][6]

Political history

Norman conquest and reign of William I (1066–1087)

Landing

Duke William's forces landed at Pevensey on 28 September 1066 and erected a wooden castle at Hastings, from which they raided the surrounding area.[7] This ensured supplies for the army, and as Harold and his family held many of the lands in the area, it weakened William's opponent and made him more likely to attack to put an end to the raiding.[8]

Battle of Hastings

On Friday, 13 October 1066, Harold Godwinson and his English army arrived at Senlac Hill just outside Hastings, to face William of Normandy and his invading army.[9] On 14 October 1066, during the ensuing battle, Harold was killed and the English defeated.[9] It is likely that all the fighting men of Sussex were at the battle, as the county's thegns were decimated and any that survived had their lands confiscated.[9] The Normans buried their dead in mass graves. There were reports that the bones of some of the English dead were still being found on the hillside some years later.

It was believed that it would not be possible to recover any remaining bones from the battle field area, in modern times, as they would have disappeared due to the acidic soil.[10] However, a skeleton that was found in a medieval cemetery, and originally thought to be associated with the 13th century Battle of Lewes turned out to be contemporary with the Norman invasion.[11] Skeleton 180 had sustained six fatal sword cuts to the back of the skull and was one of five skeletons that had suffered violent trauma. Skeleton 180 was one of 123 remains found in a medieval cemetery belonging to the Hospital of St Nicholas, which was run by monks from Lewes Priory. Many of the excavated skeletons exhibited the tell tale signs of a range of diseases common in that era, including leprosy, but only Skeleton 180 had died from head injuries. The reason why historians had originally thought that skeleton 180 was involved in the battle of Lewes is because the hospital was situated at the epicentre of the conflict. What had puzzled archaeologists though, was that most of the victims of the battle had been buried in mass grave pits dug next to the battle itself; these pits had been discovered by road builders in the 19th century. Analysis now continues on the other remains found, at the site of the hospital, to try and build up a more accurate picture of who the individuals were.[10]

Aftermath

Sussex was the first area to be systematically 'Normanised'.[12] After regrouping following the battle of Hastings, William headed to Kent and London with his main army while detachments were sent into Sussex to act as a rearguard. The Domesday Book of 1086 shows a significant drop in recorded values along the line of the army's route through Sussex to Lewes and on via Keymer, Hurstpierpoint, Steyning and Arundel to Chichester where they were met by secondary Norman forces that landed around Chichester Harbour[13] or Selsey and continued westwards to Winchester in Hampshire and Wallingford, Berkshire (now Oxfordshire).[14] A motte and bailey castle was built at Edburton soon after October 1066. A cluster of coin hoards in Sussex that were buried around 1066 suggests the coins were deposited and not recovered around the time of the Battle of Hastings.[15]

In 1067 William sailed from Pevensey to begin his triumphant tour of Normandy. Whilst at Pevensey, William seemed to make a show of distributing lands to his followers in front of a number of Anglo-Saxon noblemen who had their lands taken away.

Consequences

Members of King Harold Godwinson's family sought refuge in Ireland and used their bases in that country for unsuccessful invasions of England. The largest single exodus occurred in the 1070s, when a group of Anglo-Saxons in a fleet of 235 ships sailed for the Byzantine Empire. The empire became a popular destination for many English nobles and soldiers, as the Byzantines were in need of mercenaries. The English became the predominant element in the elite Varangian Guard, until then a largely Scandinavian unit, from which the emperor's bodyguard was drawn. Some of the English migrants were settled in Byzantine frontier regions on the Black Sea coast referred to as Nova Anglia or New England. The migrants established towns with names such as Susaco (or Porto di Susacho) thought to refer to Saxons or South Saxons (i.e. Sussex), at or near modern Novorossiysk; Londina (New London) and New York.[16]

The county was of great importance to the Normans; Hastings and Pevensey being on the most direct route for Normandy.[17] It was also necessary to guard Sussex and England from attack - to prevent raids by Danes and partly to prevent attack by the sons of Harold Godwinson,[18] as Sussex was a stronghold of the Godwin family.

Because of this the county was divided into five new baronies, called rapes, each with at least one town and a castle.[19] This enabled the ruling group of Normans to control the manorial revenues and thus the greater part of the county's wealth.[19] The bulk of the lords' estates lay in the wealthier coastal areas and enfeoffed knights on the inland manors.[20] Each castle controlled a major route inland from the lords' castle near the coast.[21]

William, the Conqueror gave these rapes to five of his most trusted Barons:[22] All were Normans who were close to William, with the exception of William de Braose, about whom little is known.[23]

- Roger of Montgomery - the combined Rapes of Chichester and Arundel.

- William de Braose - Rape of Bramber.

- William de Warenne - Rape of Lewes

- Robert, Count of Mortain - Rape of Pevensey

- Robert, Count of Eu - Rape of Hastings

By 1070 William had granted four rapes, those of Arundel, Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings. The rape of Bramber was created after 1070 by taking land from Arundel and Lewes rapes. William de Warenne also lost the hundred of East Grinstead from the rape of Lewes to the rape of Pevensey to the east.[24] To compensate de Warenne, William I gave him estates in Norfolk and Suffolk in what was known as the 'exchange of Lewes'.[25] The Count of Eu also lost land as William I founded Battle Abbey, which although within the rape of Hastings, lay outside the count's jurisdiction,[26] as the abbot of Battle answered only to the king.

William built Battle Abbey at the site of the battle of Hastings, and the exact spot where Harold fell was marked by the high altar.[9] In 1070, Pope Alexander II ordered the Normans to do penance for killing so many people during their conquest of England. In response, William the Conqueror vowed to build an abbey where the Battle of Hastings had taken place, with the high altar of its church on the supposed spot where King Harold fell in that battle on Saturday, 14 October 1066. William I had ruled that the church of St Martin of Battle was to be exempted from all episcopal jurisdiction, putting it on the level of Canterbury.

Norman influence was already strong in Sussex before the Conquest: the abbey of Fécamp had interest in the harbours of Hastings, Rye, Winchelsea and Steyning; while the estate of Bosham was held by a Norman chaplain to Edward the Confessor.[19] After the Norman conquest the 387 manors, that had been in Saxon hands, were replaced by just 16 heads of manors.[19][27]

| The owners of Sussex post 1066[27] | Number of manors | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | William I | 2 |

| 2 | Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury | 8 |

| 3 | Stigand, Bishop of Selsey* | 9 |

| 4 | Gilbert, Abbot of Westminster | 1 |

| 5 | Abbot of Fécamp | 3 |

| 6 | Osborn, Bishop of Exeter | 4 |

| 7 | Abbot of Winchester | 2 |

| 8 | Gauspert, Abbot of Battle | 2 |

| 9 | Abbot of St Edward's | 1 |

| 10 | Ode** | 1 |

| 11 | Eldred** | 1 |

| 12 | William son of Robert, Count of Eu | 108 |

| 13 | Robert, Count of Mortain | 81 |

| 14 | William de Warenne | 43 |

| 15 | William de Braose | 38 |

| 16 | Roger, Earl of Montgomery | 83 |

| Total | 387 | |

| Notes: * The See was moved from Selsey to Chichester during Stigands tenure. ** Ode and Eldred were Saxon Lords. | ||

The 16 people, in charge of the manors, were known as the Tenentes in capite in other words the chief tenants who held their land directly from the crown.[27][28] The list includes nine ecclesiasticals although the portion of their landholding is quite small and was virtually no different from that under Edward the Confessor.[27] Two of the lords were Englishmen, Ode, who had been a pre-Conquest treasurer, and his brother Eldred.[29] This means that 353 of the 387 manors in Sussex would have been wrested from their Saxon owners and given to Norman Lords by William the Conqueror[27]

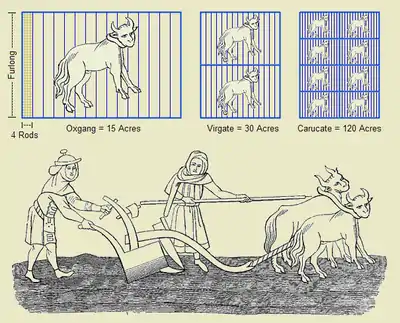

Historically the land holdings of each Saxon lord had been scattered, but now the lords lands were determined by the borders of the rape.[30] The unit of land, known as the hide, in Sussex had eight instead of the usual four virgates,(a virgate being equal to the amount of land two oxen can plough in a season).[30]

Reign of William II (1087–1100)

Following the death of William the Conqueror in 1087, William Rufus, the third son of William the Conqueror, took the kingship in 1088, separating it from his brother Robert Curthose, who remained Duke of Normandy.[31] In the rebellion of 1088, the rebels, led by William the Conqueror's half-brothers Odo of Bayeux[32] and Robert, Count of Mortain, and lord of the rape of Pevensey, with Odo the stronger of the two and the leader, decided to band together to dispose of young King William II and unite Normandy and England under a single king, the eldest Duke Robert.

To achieve this, Rufus had to secure Sussex and Kent against a retaliatory strike by Robert, who was based in Normandy. The lord of the rape of Lewes, William de Warenne, was loyal to Rufus; Robert de Mortain, lord of the rape of Pevensey, supported the rebel, Robert; Roger de Montgomery, lord of the rape of Arundel, waited, initially supporting Robert but later switching his support to Rufus. The forces of Rufus and de Warenne surrounded Pevensey Castle in a six-week siege, starving its inhabitants and capturing the rebel leader Odo. De Warenne was mortally wounded at Pevensey, dying at Lewes on 24 June 1088 .[33][34] De Mortain was pardoned and continued as lord of Pevensey.

Reign of Henry I (1100–1135)

Pevensey remained important and in 1101 Henry I spent the summer there in anticipation of attack from his brother, Robert Curthose. Curthose's attempted invasion of England was unsuccessful. Following charges against Robert de Bellême around his support for the failed invasion of Robert Curthose, Robert de Bellême fortified Arundel Castle around 1101. This led to forces of Henry I besieging Arundel Castle in 1102 for three months, building siege castles in the vicinity of Arundel probably including at Warningcamp and perhaps at Ford.[35] Henry I's forces confiscated the castle and held it himself.[36]

Reign of Stephen (1135–1154) including the Anarchy (1135–1153)

As the second wife of Henry I, Adeliza of Louvain was Queen of England from 1121 until Henry's death in 1135. On their marriage in 1121 Henry gave Adeliza the city of Chichester[13] as well as Arundel Castle, where she made her home. Because of Henry I's generosity, Adeliza was given the revenues of Rutland, Shropshire and a large district of London.[37] Adeliza gave her brother Joscelin a large estate at Petworth that was dependent on her castle of Arundel.

In 1138 Adeliza married William d'Aubigny. D'Aubigny has fought loyally for King Stephen, who made him Earl of Sussex. On 30 September 1139 Empress Matilda and her half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, landed near Arundel with a force of 140 knights,[38] thereby beginning in earnest the civil war of the Anarchy in England.[39] Adeliza received Matilda and Robert at her home in Arundel in defiance of the wishes of her second husband, who was a staunch supporter of King Stephen. She later betrayed them and handed them over when King Stephen besieged the castle. Trying to explain Adeliza's actions, John of Worcester suggests that "she feared the king’s majesty and worried that she might lose the great estate she held throughout England". He also mentions Adeliza's excuse to King Stephen: "She swore on oath that his enemies had not come to England on her account but that she had simply given them hospitality as persons of high dignity once close to her." Adeliza, was also a major benefactor to a leper hospitals at Arundel and in Wiltshire. While Matilda stayed at Arundel Castle, Robert marched north-west to Wallingford and Bristol, hoping to raise support for the rebellion and to link up with Miles of Gloucester, who took the opportunity to renounce his fealty to the king.

Stephen responded by promptly moving south, besieging Arundel and trapping Matilda inside the castle. Stephen then agreed to a truce proposed by his brother, Henry of Blois; the full details of the truce are not known, but the results were that Stephen first released Matilda from the siege and then allowed her and her household of knights to be escorted to the south-west, where they were reunited with Robert of Gloucester. The reasoning behind Stephen's decision to release his rival remains unclear. Contemporary chroniclers suggested that Henry argued that it would be in Stephen's own best interests to release the Empress and concentrate instead on attacking Robert, and Stephen may have seen Robert, not the Empress, as his main opponent at this point in the conflict. Stephen also faced a military dilemma at Arundel—the castle was considered almost impregnable, and he may have been worried that he was tying down his army in the south whilst Robert roamed freely in the west. Another theory is that Stephen released Matilda out of a sense of chivalry; Stephen was certainly known for having a generous, courteous personality and women were not normally expected to be targeted in Anglo-Norman warfare.

In 1147, following a rebellion by Gilbert de Clare, 1st Earl of Pembroke, King Stephen blockaded Pevensey Castle until its inhabitants were starved into submission. In 1153 William d'Aubigny helped arrange the truce between Stephen and Henry Plantagenet, known as the Treaty of Wallingford, which brought an end to The Anarchy. When the latter ascended the throne as Henry II, he confirmed William's earldom and gave him direct possession of Arundel Castle (instead of the possession in right of his wife (d.1151) he had previously had).

Reign of Henry II (1154–1189)

In 1187 fire destroyed Chichester Cathedral and much of the city of Chichester.

Isabel de Warenne (c. 1228–1282) daughter of William de Warenne, 5th Earl of Surrey, married Hugh d'Aubigny, 5th Earl of Arundel, son of William d'Aubigny, 3rd Earl of Arundel.

Reign of Richard I (1189–1199)

Richard I may have embarked in 1190 on the Third Crusade from Chichester.[13] In 1194, while Richard the Lionheart was being held captive in France, King John's forces lay siege to Chichester Castle.[40]

Reign of King John (1199–1216)

On 20 June 1199, after John's coronation on 6 April, the king set sail from New Shoreham to Dieppe with what Ralph of Coggeshall described as 'a mighty English host'. A truce was agreed with King Philip II of France and John visited castles and towns on Normandy's southern and eastern borders, preparing Normandy for attack from the king of France. War recommenced and by 1204 John had lost control of Normandy to Philip II.

In 1208 King John confiscated Bramber Castle from the de Braose family, after he suspected them of treachery.[40] Having lost Normandy, and fearing a naval invasion of England from Philip II of France, John sent his fleet across the English Channel to capture and destroy Philip's ships in the estuary of the River Seine as well as to attack the ports of Dieppe and Fécamp before returning to Winchelsea, where John congratulated his captains on their success.[41]

On 22 January 1215 while King John visited Knepp Castle for 4 days, confederated barons assembled in London to determine how best to check the career of this vicious king.[42] In June 1216 John signed Magna Carta, however after the king's refusal to accept the terms of Magna Carta, Rye and Winchelsea opened their gates to Prince Louis of France, the son of Philip II. Forming part of the First Barons' War, this was a bid to take the crown from the hated King John.[43] Later in 1216, Prince Louis attacked and occupied Chichester Castle.[44] Its destruction had been ordered but the order was not carried out and the castle surrendered to Louis.[45] In 1216, the castle, along with many others in southern England, was captured by the French. Louis continued to London where he was proclaimed king of England.

Pevensey Castle was also probably ordered to be made indefensible by King John.

Economy

It is estimated that in the immediate aftermath of the Normans' landing at Pevensey and the Battle of Hastings, wealth in Sussex fell by 40 per cent as the Normans sought to assert control by destroying estates or capital. From Hastings to London, estates fell in value wherever the Normans marched [46] Economically, Sussex suffered more than most counties; by 1086 wealth in Sussex was still 10-25 per cent lower than it had been in 1066. Of the counties where meaningful data has been recorded, the economies of only Yorkshire, Cheshire and Derbyshire which had been devastated through the harrying of the north fared worse than Sussex.[46] By 1300 economic output in England as a whole was probably 2 to 3 times what it was in the period before the Conquest.[46] Trade with Normandy and the rest of the Angevin Empire was increased as the Normans were familiar with their home markets. William I invited Jews to England to facilitate lending; unencumbered by rules relating to usury that pertaining to Christians.[46] Jews mainly settled in towns with mints[46] which included Chichester. Also the vast increase in infrastructure such as castle and church building and also the building of new towns helped the economy to grow.[46] In the 12th century, people had more money and wanted to spend it, so more fairs were established,[46] although belatedly many did not gain official recognition until the reign of Edward I in the late 13th century. The expansion of parishes has been described by Henry Myer-Harting as the 'economic miracle of the century' in England. In Sussex the number of parish churches approximately doubled between 1086 and 1200.[47]

William assigned large tracts of land amongst the Norman elite, creating vast estates in some areas, particularly in Sussex and the Welsh marches.

The Normans also founded new towns in Sussex, including New Shoreham (the centre of modern Shoreham-by-Sea), Battle, Arundel, Uckfield and Winchelsea.

Shipping records from the early 13th century show Winchelsea was Sussex's busiest port, closely followed by Shoreham.[48] Other ports included Arundel, where William II landed from Normandy in 1097,[49] and Seaford, where John Lackland landed on his way to being crowned King John.[50] Before the Conquest the principle port on the Adur was Steyning. In the late 11th and early 12th centuries there was a rivalry between Steyning (owned by Fécamp Abbey) in Normandy and the ports of Bramber, New Shoreham that were owned by the de Braose family, lords of the Rape of Bramber.[48] New Shoreham was one of most important Channel ports in 12th and 13th centuries.[51] William de Braose established the administrative centre of the rape at Bramber where he built a bridge and brought in a toll on all ships entering the port of Steyning. De Braose was setting up a rival parish at Bramber and after Fécamp Abbey's appeal to William I, de Braose was ordered to exhume and return 13 years' worth of burials to the churchyard at Steyning, preventing the creation of a new parish at Steyning's expense.[48] De Braose then set up the new town of New Shoreham to the south and after 1100 Fécamp Abbey focused instead on its ports of Winchelsea and Rye.[48] Shoreham is nearest Channel port to London. Shoreham visited by King John in 1199.[52] Exports from Shoreham included timber and hemp. Shipbuilding took place at Shoreham and included several galleys that were repaired for King John in 1210 and 1212.[53] The earliest known charter of the Cinque Ports, included Hastings and later Rye, Winchelsea and Seaford dates from 1155.[54]

The mint continued at Chichester throughout the period.[13] The mint at Steyning continued until reign of William II. A new mint was established at Rye, the only one south of Yorkshire to be set up in the reigns of William II and Henry I between 1087 and 1135.[55]

Salt-making continued to take place near the Adur estuary.[56]

Religion

Catholic Church

After the East-West Schism of 1054 the medieval church formally separated into a Latin-based Catholic Church in the west of Europe and a Greek-based Orthodox Church in the east of Europe. Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, there was a purge of the English episcopate in 1070.[57] Æthelric II, the Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Selsey was deposed and imprisoned and replaced with William the Conqueror's personal chaplain, Stigand.[57] During Stigand's episcopate the see that had been established at Selsey was transferred to Chichester after the Council of London of 1075 decreed that sees should be centred in cities rather than vills.[57] Bishop Ralph Luffa is credited with the foundation of the current Chichester Cathedral.[58][59] The original structure that had been built by Stigand was largely destroyed by fire in 1114.[58]

Luffa erected a timber-framed lodge at Amberley on land held by the diocese of Chichester at Amberley since Caedwalla granted it to the see of Selsey in 683. Seffrid I and Seffrid II both replaced walls and extended the building.

The archdeaconries of Chichester and Lewes were created in the 12th century under Ralph Luffa.[59] In 1199 Chichester Cathedral was re-consecrated under Bishop Seffrid II. [60][61]

The medieval church also set up various hospitals and schools in Sussex, including St Mary's Hospital in Chichester (c. 1290-1300);[62] St Nicholas' Hospital in Lewes, which was run by the monks of Lewes Priory;[63] and the Prebendal School close to Chichester Cathedral.

Monasticism

.jpg.webp)

Battle Abbey and Lewes Priory were amongst England's most important monasteries in the High Middle Ages.[64] The Cistercian abbey at Robertsbridge was the third of Sussex's 'great monasteries'.[65] 1094 saw the completion of the Benedictine Battle Abbey, which had been founded by a team of monks from Marmoutier Abbey on the River Loire. The abbey was built on the site of the Battle of Hastings after Pope Alexander II had ordered the Normans to do penance for killing so many people during their conquest of England. Monks also planned out the nearby town of Battle shortly after the conquest. Around 1081, the lord of Lewes Rape, William de Warenne and his wife Gundrada formed England's first and largest Cluniac monastery at Lewes Priory. The Priory of St Pancras was the first Cluniac house in England and had one of the largest monastic churches in the country. It was set within an extensive walled and gated precinct laid out in a commanding location fronting the tidal shore-line at the head of the Ouse valley to the south of Lewes. The monks at Lewes also administered monastic cells at Etoutteville as well as the abbey of Mortemer in Normandy.[66]

At the time of the foundation of Robertsbridge Abbey, in 1176, Robertsbridge would have been in one of the wildest and most remote parts of the Weald; this would have been an important factor in the choosing of this location for the Cistercians.[67]

Many of the monastic houses of this period were founded by Sussex's new Norman lords. As well as the foundation of Lewes Priory in 1081 by the lord of Lewes Rape, the lord of Arundel Rape, Roger de Montgomerie established Arundel Priory in 1102. Sele Priory in the Rape of Bramber was founded by the Braose family by 1126. In the Rape of Pevensey, Herluin de Conteville, step-father to William the Conqueror, established Wilmington Priory as a monastic grange, which his son, Robert, Count of Mortain presented to Grestain Abbey in Normandy.[68]

The monastic community of Selsey Abbey, which had been the seat of Sussex's bishops from the 8th century, was moved to Chichester around 1075.[69] Around 1123 Boxgrove Priory near Chichester was founded for Benedictine monks. In the north of the county, Woolynchmere Priory, later known as Shulbrede Priory was established as a house for Augustinian canons in the late 12th century. The premonstratensian Bayham Abbey was founded in 1208[70] and which became a daughter house of Prémontré Abbey in France.

Pilgrimage

Sussex lay on part of the route of the Way of St James to the shrine of the apostle of St. James the Great on the town of Santiago de Compostela in the Crown of Castille (now Spain). Various Sussex ports, including Winchelsea, Shoreham and Lewes, were embarkation points to cross the English Channel and connect to the Way of St James via the Via Turonensis through the Kingdom of France.

Crusades

Chichester[13] and Shoreham may have been used as a point of departure for the crusades. Shoreham supplied three ships for Richard I for the Third Crusade.[53]

Sussex had strong links with the military orders of the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller. Founded in 1119, the Knights Templar established centres in Sussex including a local headquarters, or preceptory, at Shipley from around 1125, with other centres at Sompting from 1154[71] and at the port of Shoreham by 1170.[56] The church at Shipley is the earliest surviving church of the Templars in England and dates from the 1130s.[72] The Hospitallers established a centre at Poling and another at Shoreham in 1190.[56] Various Sussex magnates went on crusade including Philip de Braose, lord of Bramber, went on crusade probably in 1128.[73] William de Warenne III, lord of the rape of Lewes, made annual gifts from his estate at Lewes to the knights Templar and around 1146 went on crusade[74] where he was killed in battle in 1148.

Anchorites

In the 12th and 13th centuries Sussex had high numbers of anchorites which reduced into the 14th century.[75][76]

Geography

The county boundary was long and somewhat indeterminate on the north, owing to the dense forest of Andredsweald.[78] Evidence of this is seen in Domesday Book by the survey of Worth and Lodsworth under Surrey, and also by the fact that as late as 1834 the present parishes of North and South Ambersham in Sussex were part of Hampshire.[79]

Initial settlement by the Normans took places as the William the Conqueror built castles in which he placed his most trusted men, who persuaded other knights to garrison and guard the castles.[80] In common with some other areas of eastern England like Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Essex and Kent, Sussex received some of the most migrants from what is now France after the Norman conquest.[81]

Sussex's population in 1086 has been estimated at about 66,000, doubling to 123,000 by 1290.[82] In the High Middle Ages, the Sussex coast was one of the most densely populated parts of England. At the time of the Domesday Book in 1086 coastal Sussex and parts of Suffolk and Norfolk were the only parts of England to record a population density of 20 people per square mile, twice the average for England.[83] Coastal Sussex remained amongst the most densely populated areas of England through the 12th century. Other populous areas of England at this time included eastern East Anglia, parts of Kent and a series of districts between Somerset and the Humber Estuary in Yorkshire.[84]

Governance

William the Conqueror set out compact lordships across Sussex in what were termed 'rapes'. Shortly after 1066 there were four rapes: Arundel, Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings.[85] By the time of the Domesday Book, William the Conqueror had created the rape of Bramber out of parts of the Arundel and Lewes rapes, so that the Adur estuary could be better defended.[86][87][88] The rape of Arundel was much larger than its present size as included what was to become the rape of Chichester, which did not become separate until the mid 13th century.[87]

Although the origin and original purpose of the Rapes is not known, their function after 1066 is clear. With its own lord and sheriff, each Rape was an administrative and fiscal unit.[4]

Each rape has its own court held by the lord of the rape and their knights. For instance the court of the rape of Hastings would hear all cases to life and limb within the rape, meeting every three weeks to report on all things which happen within the barony. From 1198 the common gaol for Sussex was at Chichester Castle.[49] In what was the only directly provable example of Continental innovation in English local government in the reign of Stephen, Queen Adeliza established her brother Joscelin from Brabant at Petworth and adopted the Brabazon method of local government at Arundel giving power to the castellans (such as those at Brussels and Louvain.[89]

By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086 Sussex probably had seven boroughs - certainly Chichester, Arundel, Steyning, Lewes and Pevensey, and probably Hastings and Rye.[49] Seaford also probably had borough status by 1140, and certainly by 1235.[50] New Shoreham probably had borough-like status in 1208 and had borough status by 1235.[48]

As with other parts of England, the tenants-in-chief of Sussex would have attended the curia regis, the successor to the Witenagemot of the Anglo Saxon period and the precursor to the English parliament. Attendees at the magnum concilium from Sussex would have included the lords of the rapes as well as the abbot of Battle.

Culture

Architecture

In terms of architecture, the impact of the Norman conquest has been described as "dramatic, far-reaching and visible".[91] Some of the enormous Romanesque buildings of Sussex and the rest of southern England, such as Chichester Cathedral, Battle Abbey, Lewes Priory and the church at New Shoreham were amongst the largest and most daring in Europe that led directly to Gothic architecture[92] Important Norman architecture in Sussex includes Chichester Cathedral, the ruins of Lewes Priory and Battle Abbey as well as Norman remains in the castles at Arundel, Bramber, Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings.

Norman castles typically consisted of a tower keep and a hall keep. The keep at Pevensey Castle is nationally significant and is entirely different from most castles as enormous buttresses were built which extended 9 metres (30 ft) beyond the walls and were over 6 metres (20 ft) thick.[93] Lewes Castle is, with Lincoln Castle, one of only two castles in England with two mottes.

Completed in the early 12th century, the designs of Battle Abbey for the rounded apse, ambulatory and radiating chapels were taken from Rouen Cathedral and were repeated at Canterbury Cathedral in the 1070s and Worcester Cathedral in the 1080s.[94][95] Battle Abbey also took the basic elements of its building from Rouen Cathedral and the Abbey of Saint-Étienne, Caen. At 128 metres (420 ft) long and with an internal vault height of 28 metres (92 ft) at the altar and 35 metres (115 ft) at the crossing, Lewes Priory was the largest church in Sussex, being longer than Chichester Cathedral including its Lady Chapel, and is comparable in scale to the original form of Ely Cathedral or the surviving form of Lichfield Cathedral.

Most churches in this era were built to simple designs, consisting of a nave and a chancel; others included a central tower or transepts and sometimes a western tower and aisle.[96] Important churches in Sussex with features from the Saxo-Norman overlap include Sompting, Clayton and Bosham.[97] By the 12th century, churches in Sussex were built less exaggeratedly tall in proportion and with more ornamental designs[98] in the transitional style, as architecture moved from Norman towards Gothic. Notable minster or parish churches from the late Norman period include the churches at New Shoreham (c 1120-1150) and Rye.[99] Around 1160 ornamental styles became more common, with zigzags around windows as at Climping or around doors at Arundel, chevrons at Burpham and diamonds at Broadwater.[100] In the late 12th century the Knights Templar remodelled Sompting church, producing an 'exquisitely detailed' apse in the south transept in what Ian Nairn referred to as a completely different 'latest Norman' style similar to a style then current in Gascony.[101]

As well as Battle Abbey, other Sussex churches make use of the designs of churches in Normandy. The churches of Old Shoreham and Boxgrove Priory have similar architecture to Lessay Abbey.[102] Uncommon in England except for in Sussex and Kent, which were relatively close to Normandy, many Sussex churches were built with apses.[103] Examples include churches at Newhaven, Keymer,[104] North Marden and Upwaltham. Three examples of rounded west church towers of the type most commonly found in East Anglia exist around the lower Ouse valley at Piddinghoe, Southease and St Michael's at Lewes.[105]

Many prestigious Sussex buildings in the High Middle Ages used Caen stone from Normandy which was imported into Sussex's ports and river estuaries, even reaching places such as Shulbrede Priory in the Weald on the Sussex-Surrey border, which were away from waterways.[106] Ships carried loads of up to 40 tonnes of Caen stone at a time across the English Channel from Normandy.[90] One of the most widely used building stones to be imported, Caen stone was typically used in squared blocks or used in ornate decorative column or arch work. Buildings using Caen stone include Chichester Cathedral, Lewes Priory, Battle Abbey and the churches of Steyning, Kingston Buci and Buncton.[90]

Art

.jpg.webp)

With its own masons' yard, Lewes Priory manufactured decorated glazed floor tiles and had a school of sacred painting that worked throughout Sussex.[107] The calibre of surviving figurative carvings that are displayed at the British Museum is of a highly sophisticated order. Dating from around the 12th century, the 'Lewes Group' of wall paintings can be found in several churches across the centre of Sussex, including at Clayton, Coombes, Hardham, Plumpton and now-lost paintings at Westmeston. Some of the paintings are celebrated for their age, extent and quality: Ian Nairn calls those at Hardham "the fame of Hardham",[108] and descriptions such as "fine",[109][110] "Hardham's particular glory"[111] and "one of the most important sets in the country"[112] have been applied.

Language

- use of Anglo-Norman language by ruling class; Norman French was almost exclusively used as a spoken language

- use of Latin as the language of all official written documents

- use of Old English which evolved into Middle English by common people.

At the start of the High Middle Ages Sussex had its own dialect of Old English which was in effect part of a continuum of southern English dialect from Kent in the east to Wessex in the west.[113][114] As the influence of the Norman language increased, the Anglo-Norman language developed and the Sussex dialect of Old English evolved into a dialect of Middle English.

Literature

The Proverbs of Alfred is a collection of sayings supposedly from King Alfred said to have been uttered at Seaford that were written in the mid-12th century in Middle English. It is likely to have been written by someone living in or originating from southern Sussex, probably from either Lewes Priory or Battle Abbey.[115]

See also

Bibliography

- Allen Brown, Reginald, ed. (1980). Proceedings of the Battle Conference on Anglo-Norman Studies:1979. II.

- Armstrong, Jack Roy (1974). A History of Sussex. Phillimore & Co Ltd. ISBN 9780850331851.

- Brandon, Peter (2006). Sussex. Robert Hale. ISBN 9780709069980.

- Crouch, David (2000). The reign of King Stephen, 1135-1154. Longman. ISBN 9780582226586.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton; Wright, Duncan W. (2017). The Anarchy: War and Status in 12th-century Landscapes of Conflict. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781781382424.

- Dalton, Paul; Insley, Charles; Wilkinson, Louise J., eds. (2011). Cathedrals, Communities and Conflict in the Anglo-Norman World. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843836209.

- Dodgshon, Robert A.; Butlin, Robin Alan, eds. (1990). An Historical Geography of England and Wales. Academic Press. ISBN 9780122192531.

- Evans, G.R. (2007). The Church in the Early Middle Ages: The I.B.Tauris History of the Christian Church. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9780857711373.

- Fernie, Eric (2000). The Architecture of Norman England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198174066.

- Golding, Brian (2013). Conquest and Colonisation: The Normans in Britain, 1066-1100. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 9781137328960.

- Green, Judith A. (2002). The Aristocracy of Norman England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521335096.

- Grehan, John; Mace, Martin (2012). Battleground Sussex. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1848846616.

- Herbert McEvoy, Liz (2010). Anchoritic Traditions of Medieval Europe. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 9781843835202.

- Hillaby, Joe; Hillaby, Caroline (2013). The Palgrave Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0275994792.

- Hurlock, Kathryn (2011). Wales and the Crusades, C.1095-1291. Studies in Welsh History. University of Wales Press. ISBN 9780708324271.

- Lowerson, John (1980). A Short History of Sussex. Folkestone: Dawson Publishing. ISBN 0-7129-0948-6.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (2014). Religion, Politics and Society in Britain 1066-1272. Routledge. ISBN 9781317876625.

- Melton, J. Gordon (2014). Faiths Across Time: 5,000 Years of Religious History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610690263.

- Morris, Marc (2015). King John: Treachery and Tyranny in Medieval England: the Road to Magna Carta. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781605988856.

- Nairn, Ian; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1965). Sussex. Pevsner Architectural Guides. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300096774.

- Naylor, Murray (2013). England's Cathedrals by Train: Discover how the Normans and Victorians Helped to Shape our Lives. Remember When. ISBN 978-1473826960.

- Phillips, C.B.; Smith, J.H. (2014). The South East from 1000AD. Regional History of England. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317871705.

- Rouse, Robert Allen (2005). The Idea of Anglo-Saxon England in Middle English Romance. Studies in Medieval Romance Series. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781846154034.

- van Gelderen, Elly (2006). A History of the English Language. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9789027232366.

References

- Armstrong 1974, p. 43

- Armstrong 1974, p. 43

- Hudson, T P, ed. (1980). "A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 1, Bramber Rape (Southern Part) - Bramber Rape". British History Online. pp. 1–7.

- Thorn, Caroline; Thorn, Frank (June 2007). "Sussex" (RTF). University of Hull. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- Brandon 2006, p. 83

- Golding 2013, p. 65

- Bates William the Conqueror pp. 79–89

- Marren 1066 p. 98

- Seward. Sussex. pp. 5–7.

- Edwina Livesay. Skeleton 180 Shock Dating Result in Sussex Past and Present Number 133. p. 6

- For detail on the excavation see Luke Barber and Lucy Siburn. The medieval hospital of St Nicholas, Lewes, East Sussex in SAC Vol. 148. pp. 79-109

- Lowerson 1980, p. 47

- "The City of Chichester: Historical introduction". Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- Lowerson 1980, p. 47

- Creighton & Wright 2017, p. 150

- Green, Caitlin (19 May 2015). "The medieval 'New England': a forgotten Anglo-Saxon colony on the north-eastern Black Sea coast". Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Armstrong 1974, pp. 48-58

- Green 2002, p. 58

- Mark Gardiner and Heather Warne. Domesday Settlement in Kim Leslie's. An Historical Atlas. pp. 34–35

- Golding 2013, p. 66

- Golding 2013, p. 65

- Armstrong 1974, pp. 48-58

- 2002

- Salzman, L F, ed. (1940). "A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 7, the Rape of Lewes". British History Online. pp. 1–7.

- Golding 2013, p. 66

- Golding 2013, p. 66

- Horsfield. The History of the county of Sussex. Volume I. pp. 77–78

- Friar. The Sutton Companion to Local History. p. 429

- Dennis Haselgrove. The Domesday Record of Sussex in Brandon's South Saxons. p. 193

- Brandon. The South Saxons. Chapter IX. The Domesday Record of Sussex

- Lowerson 1980, p. 48

- Yarde, Lisa (16 May 2011). "15 Minutes of Fame: The Rebellion of 1088". unusualhistoricals.blogspot.com. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- G. E. Cokayne, The Complete Peerage, vol. xii/1 (The St. Catherine Press, London, 1953), pp. 494–95.

- Hyde Abbey, Liber Monasterii de Hyda: Comprising a Chronicle of the affairs of England, ed. Edward Edwards (Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, London, 1866), p. 299.

- "Arundel Siege Castles". Gatehouse Gazeteer. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Harris, Roland B (March 2009). "Arundel Historic Character Assessment Report" (PDF) (PDF). Sussex Extensive Urban Survey. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- http://site.ebrary.com/lib/mtholyoke/docDetail.action?docID=10404924

- King 2010, p. 116

- Crouch 2000, p. 103

- Grehan & Mace 2012, p. 38

- Morris 2015

- Symonds, Richard. "Knepp Castle Timeline" (PDF) (PDF). Knepp Castle Estate. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- Greahn & Mace 2012, p. 69

- Grehan & Mace 2012, p. 38

- "VCH: The City of Chichester: General Introduction". Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- "Brentry - How Norman rule reshaped England - England is indelibly European". The Economist. 24 December 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- Mayr-Harting 2014, p. 112

- Harris, Roland B. (January 2009). "Shoreham Historic Character Assessment Report, Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS)" (PDF) (PDF). p. 15. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- Harris, Roland B. (March 2009). "Arundel Historic Character Assessment Report" (PDF) (PDF). Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- Harris, Roland B. (March 2005). "Seaford Historic Character Assessment Report" (PDF). Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS). Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "VCH Old and New Shoreham". Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "VCH Old and New Shorham". Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Harris, Roland B. (January 2009). "Shoreham Historic Character Assessment Report, Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS)" (PDF) (PDF). p. 16. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- Stanton 2015, p. 233

- Creighton & Wright 2017, p. 139

- Harris, Roland B. (January 2009). "Shoreham Historic Character Assessment Report, Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS)" (PDF) (PDF). p. 17. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- Kelly. The Bishopric of Selsey in Mary Hobbs. Chichester Cathedral. p. 9

- Stephens. Memorials. p. 47

- Hennessy. Chichester Diocese Clergy Lists. pp. 2–3

- Naylor 2013

- Melton 2014, p. 782

- "Sussex". Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- "Yesterday Channel Reveals Grisly Mass Graves of Lewes". Sussex Express. 24 February 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- Armstrong 1974, p. 64

- Armstrong 1974, p. p64-65

- Dalton, Insley & Wilkinson 2014, p. 223

- Armstrong 1974, pp. 64-65

- Armstrong 1974, p. 63

- Kelly. The Bishopric of Selsey in Hobbs. Chichester Cathedral: An Historic Survey. pp. 1–10.

- Armstrong 1974, p. 62

- Armstrong 1974, p. 63

- Fernie 2000, p. 191

- Hurlock 2011

- Evans 2007

- Hughes-Edwards, Mari. "Solitude and Sociability: The World of the Medieval Anchorite". Building Conservation.com. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Herbert McEvoy 2010, p. 140

- Hillaby & Hillaby 2013

- Brandon. The South Saxons. Ch. VI. The South Saxon Andredesweald.

- Carol Adams. Medieval Administration in Kim Leslie's. An Historical atlas of Sussex. pp. 40–41.

- Golding 2013, p. 66

- "The Norman conquest: women, marriage, invasion". Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- Broadberry, Stephen; Campbell, Bruce M.S.; van Leeuwen, Bas (27 July 2010). "English Medieval Population: Reconciling Time Series and Cross Sectional Evidence" (PDF) (PDF). Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Dodgshon & Butlin 1990, p. 71

- Creighton & Wright 2017, p. 15

- 2002

- Brandon 2006

- "Victoria County History - The rape of Chichester". British History Online. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- "Victoria County History - The rape and honour of Lewes". British History Online. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- Crouch 2000, p. 89

- "Strategic Stone Study: A Building Stone Atlas of West Sussex (including part of the South Downs National Park)" (PDF) (PDF). English Heritage. June 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Fernie 2000, p. 19

- Phillips & Smith 2014, p. 39

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 43

- Brandon 2006, p. 86

- Fernie 2000, p. 26

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 43

- Fernie 2000, p. 218

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 24

- Fernie 2000, p. 228

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 25

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 25

- Phillips & Smith 2014, p. 39

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 43

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 43

- Nairn & Pevsner 1965, p. 43

- Armstrong 1974, p. 64

- Baker, Audrey. Lewes priory and the early group of wall paintings in Sussex. Walpole Society, 31 (1946 for 1942-3), 1-44. Walpole Society. ISSN 0141-0016.

- Nairn, Ian and Nikolaus Pevsner (1965). The Buildings of England - Sussex. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-300-09677-4.

- Fisher, E.A. (1970). The Saxon Churches of Sussex. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4946-5.

- Salter, Mike (2000). The Old Parish Churches of Sussex. Malvern: Folly Publications. ISBN 1-871731-40-2.

- Wales, Tony (1999). The West Sussex Village Book. Newbury: Countryside Books. ISBN 1-85306-581-1.

- Whiteman, Ken and Joyce Whiteman (1998). Ancient Churches of Sussex. Seaford: S.B. Publications. ISBN 1-85770-154-2.

- van Gelderen 2006, p. 75

- Davis, Dr. Graeme (March 2016). "The Dialect of our Sussex Ancestors". Sussex Family Historian. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Rouse 2005, pp. 38-39