Symphyotrichum lateriflorum

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (formerly Aster lateriflorus) is a species of flowering plant of the aster family (Asteraceae) native to eastern and central North America. Commonly known as calico aster, starved aster, and white woodland aster,[4] it is a perennial, herbaceous plant that may reach 120 centimeters (4 feet) high and 30 centimeters (12 inches) across.[5] As composite flowers, each flower head has many tiny florets put together into what appear as one, as do all plants in the family Asteraceae.

| Symphyotrichum lateriflorum | |

|---|---|

| |

_crop-1.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Symphyotrichum |

| Subgenus: | Symphyotrichum subg. Symphyotrichum |

| Section: | Symphyotrichum sect. Symphyotrichum |

| Species: | S. lateriflorum |

| Binomial name | |

| Symphyotrichum lateriflorum | |

| |

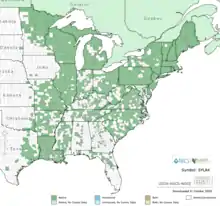

| USDA PLANTS county-level distribution map[1] | |

| Synonyms[2][3] | |

|

Basionym

Most recently Others listed alphabetically List

| |

The flowers of calico aster are small compared to most Symphyotrichum species. They have an average of 7–15 short white ray florets, which are rarely tinted pink or lavender. The flower centers, composed of disk florets, begin as cream to yellow and often become pink, purple, or brown as they mature. There are roughly 8–16 disk florets, each with five lobes that strongly reflex (bend backwards) when open.[5] The mostly hairless leaves have a characteristic hairy midrib on their back faces, and branching is usually horizontal[5] or in what can appear to be a zigzag pattern.[6]:174 Flower heads grow along one side of the branches and sometimes in clusters at the ends.[7][8]:842

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum grows in a variety of habitats and can be found throughout most of the eastern and east-central United States and Canada. There is also a native population in the state of Veracruz, Mexico.[2] It is a conservationally secure species[9] whose late-summer and fall appearing flowers play an important role for small, late-season pollinators and nectar-seeking insects such as sweat bees, miner bees, and hoverflies.[7]

In addition to occurring naturally in several varieties,[1] Symphyotrichum lateriflorum has multiple cultivars. As a garden plant, it has been grown for at least 250 years in Europe,[10]:204 and some modern-day cultivars are 'Bleke Bet',[11] 'Lady in Black',[12] and 'Prince'.[13] It has long been used by indigenous Americans as a medicinal plant.[14]

Name

The specific epithet (second part of the scientific name) lateriflorum is a combination of the Latin words for side (lateri, literally meaning flank) and flower (florum) in reference to the fact that the flowers of this species generally grow on one side of the branch.[15] Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is commonly known as calico aster, starved aster, white woodland aster,[4] side-flowering aster,[16] side-flower aster, goblet aster, one-side aster, one-sided aster, farewell summer,[4] and calico American-aster.[17] Along with other asters that bloom in the fall, Symphyotrichum lateriflorum may be called a Michaelmas Daisy.[18] There are indigenous American names for this plant including the Meskwaki word no'sîkûn and the Potawatomi word pûkwänä'sîkûn, both as spelled by ethnobotanist Huron Herbert Smith.[14]

Aster comes from the Ancient Greek word ἀστήρ (astḗr), meaning star, referring to the shape of the flower. The word aster was used to describe a star-like flower as early as 1542 in German physician and botanist Leonhart Fuchs' book De historia stirpium commentarii insignes, Latin for Notable Commentaries on the History of Plants. An old common name for Astereae species using the suffix -wort is starwort, also spelled star-wort or star wort. An early use of this name can be found in the same work by Fuchs as Sternkraut, translated from German literally as star herb.[19]

The name star-wort was in full use by Scottish botanist William Aiton in his 1789 Hortus Kewensis. Scientific names that were later changed to be synonyms of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum had common names such as diffuse white-flower'd star-wort and pendulus star-wort in this work.[10]:197–210

A dry summer in England in 1898 inspired Gardening World Illustrated to write the following:

The Michaelmas Daisies, with their love for deep, rich, soil and plenty of water, have not escaped, although with their tough constitutions they have not suffered so much as might be expected. For this we cannot be too thankful, for what would our gardens be in autumn but for the Starworts?[20]

In languages other than English, Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is called Sommerens Farvel (Danish);[21] kleine aster (Dutch);[22] aster latériflore (French);[4] Waagerechte Aster,[23][24] Ruten-Aster, Waagerechte Herbst-Aster,[24] and Kattun-Aster (German);[4] aster bocznokwiatowy, aster bocznolistny, and aster perkalowy (Polish);[25] and, grenaster (Swedish).[26]

Description

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is a clump-forming herbaceous perennial that grows 20–120 centimeters (8–47 inches) tall and up to 30 cm (12 in) wide.[5] It can have a different appearance throughout its lifespan or a season. For example, whereas a mature or returning plant, or one late in the season, may have one or more stiff stems that reach close to maximum height with several arching branches and multiple clusters of flowers (known as inflorescences), an early or first-year plant may have one short and somewhat floppy stem with several large leaves and end abruptly with one flower head in the center.[27]

Roots

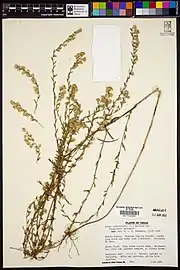

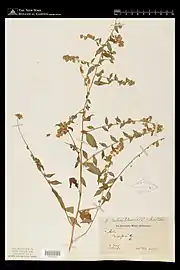

The roots of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum have short and woody branched caudices, and can have short rhizomes that may produce offsets.[5] In this section are cropped photos of caudices from dried specimens of S. lateriflorum that are stored in the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) Steere Herbarium.

No rhizomes, under 25 roots serving four stems, caudex width is about 4 cm (1.6 in), longest root is about 8 cm (3 in).[28]

No rhizomes, under 25 roots serving four stems, caudex width is about 4 cm (1.6 in), longest root is about 8 cm (3 in).[28] No rhizomes, about 3 cm (1.2 in) wide with approximately 25–30 small roots supporting one stem. Longest root is about 8 cm (3 in).[29]

No rhizomes, about 3 cm (1.2 in) wide with approximately 25–30 small roots supporting one stem. Longest root is about 8 cm (3 in).[29] No rhizomes, 5 cm (2 in) at widest point, longest roots are over 9 cm (3.5 in), and there is one woody stem.[30]

No rhizomes, 5 cm (2 in) at widest point, longest roots are over 9 cm (3.5 in), and there is one woody stem.[30] Two rhizomes lengths 6 cm (2.4 in), 3 cm (1.2 in), and a third may be forming. Four stems, and many secondary roots about 10 cm (4 in).[31]

Two rhizomes lengths 6 cm (2.4 in), 3 cm (1.2 in), and a third may be forming. Four stems, and many secondary roots about 10 cm (4 in).[31]

Stems

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum has from one to five herbaceous stems growing from the root base.[5] These stems can be a reddish or purplish color, often with a woody appearance, or a shade of green, sometimes dark and flexible. Characteristics can depend on the prevalence of sun, with the green stems occurring more likely in the shade.[6]:172

Slender and wiry inflorescence-filled branches grow from the stems at almost a right angle (divaricate) or in long arches. Shorter branches may ascend rather than arch.[5] Stems and branches can be covered with fine soft hair (pilose), but sometimes the amount of hair is reduced farther from the base, mid-stem, or as it goes up the stem. The hair will usually be in vertical lines, particularly on the inflorescence branches.[27]

Leaves

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum has alternate and simple leaves.[32] Characteristics vary among leaves on the same plant, and on plants in different environments and areas of the range.[7] Leaves occur at the base, on stems, and on inflorescence branches. The farther away from the base the leaves are, the smaller they become, sometimes markedly so. By the time flowers appear, the leaves at the base and stem have often withered or fallen.[5] Leaves have fine, reticulate veins[lower-alpha 1][33]:1225 and little to no hair (glabrous) except for the key characteristic of hair on the abaxial midrib (back main leaf vein).[6]:177 This abaxial midrib hair can sometimes all but disappear as the plant ages within a season.[7]

Basal (bottom) leaves vary in shape from oblanceolate, lance-ovate, ovate, spatulate, to suborbiculate (nearly circular). They are thin and the least lance-shaped, with a short or no leafstalk (petiole). Basal leaf size varies in both length and width measuring about 3–35 millimeters (0.3–3.5 centimeters, or up to about 1.5 inches) long by 7–25 mm (0.7–2.5 cm, or up to about an inch) wide. The surfaces feel slightly rough to the touch, and the edges are wavy or saw-toothed. Leaves may or may not come to a point at the end depending upon their shape.[5]

Lower and middle stem leaves have no leafstalk (known as sessile), or they have a very short leafstalk (subpetiolate) with wings. The shapes of the stem leaves vary from ovate or elliptic to elliptic-oblanceolate or lanceolate, rarely linear-lanceolate. Sizes become much smaller the farther they grow from the base. They are about 5–10 cm (2–4 in) long by 1–2 cm (0.4–0.8 in) wide.[lower-alpha 2][5]

Distal leaves, higher on the stem and on the branches with the flower heads, are also sessile. Their margins are sometimes smooth on the edges with no teeth or lobes (called entire). Sizes range from 1 cm (0.4 in) to 15 cm (6 in) long by 1 mm to 3 cm (1.2 in) wide. The more distal, the smaller they are, and this change can occur abruptly.[5]

Flowers

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is a late-summer and fall blooming perennial, with flower heads opening as early as July[7] in some locations and as late as November[32] in others. The flower heads grow in racemose paniculiform arrays, secund (to one side) along the upper sides of the branches (known as peduncles).[7] These inflorescences are up to 15 cm (6 in) wide and 25 cm (10 in) long.[34] The flower heads at the ends of the peduncles mature approximately one week before those on the rest of the plant.[8]:842

.jpg.webp)

Each flower head is 8–16 mm (0.3–0.6 in) diameter when in bloom.[5][34][35] There is little to no floral scent,[34] and the flower head is either sessile or with a usually pilose peduncle of its own which is less than 1 cm (0.4 in) long.[5] At the base of the flower head are from one to seven bracts which look like (and technically are) small leaves that grade into the phyllaries.[5]

Involucres and phyllaries

On the outside the flower heads of all members of the family Asteraceae are small bracts that look like scales. These are called phyllaries, and together they form the involucre that protects the individual flowers in the head before they open.[lower-alpha 3][36]:29 The involucres of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum are cylinder-bell in shape and usually 4–6 mm[lower-alpha 4] long.[5]

The phyllaries are appressed or slightly spreading. The shape of the outer phyllaries is oblong-lanceolate or oblong-oblanceolate, and the inner phyllaries are linear.[5] They are in 3–4 (sometimes up to 6) unequal rows, meaning they are staggered and do not end at the same point,[5] and may be smooth or have hairs.[8]:835 The sparsely-haired margins of each phyllary may appear white or light green, but are translucent or sometimes reddish. The phyllaries have green zones (chlorophyllous zones) that are lanceolate, lens, or diamond-shaped and have green or purplish tips.[5][35][8]:836

Florets

Each flower head is made up of ray florets and disk florets in about a one to one (1:1) ratio,[8]:843 with the former developing 3–4 days before the latter.[8]:842 The 7–15[lower-alpha 5] ray florets grow in one series and are usually white, rarely pinkish or purplish.[5][27] They average 4–5 mm long, but can be as short as 3 mm and as long as 8 mm.[17][5] They are 0.9–1.2 mm wide[5] and linear-oblong in shape.[34] Ray florets in the Symphyotrichum genus are exclusively female, each having a pistil (with style, stigma, and ovary) but no stamen; thus, ray florets accept pollen and each can develop a seed, but they produce no pollen.[27]

The disks have 8–16[lower-alpha 6] florets[17][5] that start out as cream or light yellow and after opening, may turn pink, then purple or light brown after pollination.[lower-alpha 7][8]:836 Each disk floret is cylindrical or funnel-shaped and shallow at 3–5 mm in depth,[5][8]:836 and is made up of 5 petals, collectively a corolla, which open into 5 lanceolate lobes[lower-alpha 8] comprising 50-75% of the depth of the floret.[8]:837 The lobes become strongly reflexed (bent sharply backwards) once open.[5] Disk florets in the Symphyotrichum genus are bisexual, each with both male (stamen, anthers, and filaments) and female reproductive parts; thus, a disk floret produces pollen and can develop a seed.[27]

Close-up of involucre, phyllaries, and bracts on S. lateriflorum flower head. The involucre is bell-shaped (campanulate), and the green zone of each phyllary is shaped like a lens.

Close-up of involucre, phyllaries, and bracts on S. lateriflorum flower head. The involucre is bell-shaped (campanulate), and the green zone of each phyllary is shaped like a lens. Microscopic photo of the involucre of a flower head of S. lateriflorum plant showing phyllary detail. The green zone of each phyllary is shaped like a lens. The inner phyllaries are much longer and linear-shaped than the outer ones, and visible on the edges of each phyllary are white-looking translucent margins.

Microscopic photo of the involucre of a flower head of S. lateriflorum plant showing phyllary detail. The green zone of each phyllary is shaped like a lens. The inner phyllaries are much longer and linear-shaped than the outer ones, and visible on the edges of each phyllary are white-looking translucent margins. Microscopic photo of S. lateriflorum flower head showing disk florets closed, open and reflexed, anther cylinders, stamens, styles (separating and separated), pollen has been collected. There are ray florets with separated styles and some pappi exposed.

Microscopic photo of S. lateriflorum flower head showing disk florets closed, open and reflexed, anther cylinders, stamens, styles (separating and separated), pollen has been collected. There are ray florets with separated styles and some pappi exposed. S. lateriflorum microscopic photo of a single ray floret and a two disk florets, lobes of the disk florets reflexed. One separated ray floret style and a clump of disk floret pappi are viewable. Spent anther tubes are protruding from the disk florets.

S. lateriflorum microscopic photo of a single ray floret and a two disk florets, lobes of the disk florets reflexed. One separated ray floret style and a clump of disk floret pappi are viewable. Spent anther tubes are protruding from the disk florets.

Fruit

The fruits (seeds) of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum are not true achenes but are cypselae, resembling an achene but surrounded by a calyx sheath. This is true for all members of the Asteraceae family.[37] After pollination, they mature in 3–4 weeks[8]:842 and become gray or tan with an oblong-obovoid shape, 1.3–2.2 mm long with 3–5 nerves, and sparsely strigillose (with a few stiff, slender bristles) on their surface. They also have pappi (tufts of hairs) which are white to pinkish in color and 3–4 mm long.[5]

Taxonomy

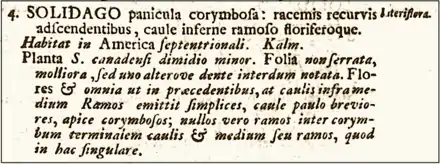

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is a member of the genus Symphyotrichum, sometimes called American-asters.[39] Its basionym (original scientific name) is Solidago lateriflora L., and it has many taxonomic synonyms. Its name with author citations is Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) Á.Löve & D.Löve. Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, in 1753, formally described what we know today as Symphyotrichum lateriflorum. The letter L followed by a period (or dot), written L., is the standard botanical author abbreviation for Carl Linnaeus.[40] Likewise, Á.Löve and D.Löve are the abbreviations for Icelandic botanists Áskell Löve and Doris Löve, respectively.[41][42] Linnaeus' abbreviation is placed in parentheses because his authorship was retained when Áskell and Doris Löve cited Solidago lateriflora L. as the basionym when renaming the species.[43]

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is classified in the subgenus Symphyotrichum, section Symphyotrichum, subsection Dumosi.[44] It is one of sixteen "bushy asters and relatives".[38] The word Symphyotrichum has as its root the Greek symph, which means coming together, and trichum, which means hair. The species name lateriflorum is a combination of the Latin words for side (lateri, translated literally asa flank) and flower (florum) in reference to the fact that the flowers of this species generally are located on one side of the branch.[15]

History

In 1748, Linnaeus' apostle Pehr Kalm traveled to North America from Europe. He stayed for two-and-a-half years studying flora and fauna, and gathering specimens for study by Linnaeus, returning home in 1751. Kalm's travels in North America took him to Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and southeastern Canada.[45] One of the samples he gathered was described by Linnaeus as Solidago lateriflora, the basionym of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum. Linnaeus recorded the specimen's origin as "Habitat in America Septentrionali" (Latin for "It grows in North America"), and that it was provided by Kalm. Linnaeus classified this plant in the genus Solidago,[46]:879 which now contains over 120 of the many species known today as goldenrods.[47] At that time, Linnaeus sorted fifteen of his available specimens into this genus and included them in his two-volume Species Plantarum (1753).[46]:878–881

In 1789, Scottish botanist William Aiton included Solidago lateriflora in his Hortus Kewensis,[10]:211 the first edition of a catalogue of the plants cultivated at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew where he had been the director since 1759.[48] In separate entries, he also described an Aster diffusus, Aster divergens, and Aster miser, and in the A. miser, he referenced the A. miser of Linnaeus "excluso synonymo Dillennii".[lower-alpha 9][10]:205 The Catalogue of Life (COL) 2020 Annual Checklist entry for Symphyotrichum lateriflorum includes Aster diffusus Dryand. ex Aiton as a synonym, but not Aster miser L. or Aster miser Aiton.[3] It does include Aster miser Nutt. which was described by English naturalist Thomas Nuttall in 1818. Nuttall stated that what he described appeared "to be the A. miser of Linnaeus, but probably not that of Aiton."[50]:158 Aster divergens Aiton is also listed as a synonym.[3]

In 1889, American botanist Nathaniel Lord Britton combined Solidago lateriflora L., Aster diffusus Aiton, and Aster miser Aiton into one species named Aster lateriflorus (L.) Britton, with Solidago lateriflora L. as the basionym.[51] Aster lateriflorus remained the name until the broad and polyphyletic circumscription of the genus Aster was divided.[52] This species was moved to Symphyotrichum in 1982 by Áskell and Doris Löve during their study of plant chromosomes[53] making its binomial name Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) Á.Löve & D.Löve where it currently remains.[3] The infraspecies were subsequently moved by American botanist Guy L. Nesom in 1995.[54]:285

In a 1928 study of Aster lateriflorus and close relatives, American botanist Karl McKay Wiegand noted how environmental differences likely affected leaf and flower head characteristics, causing botanists to name specimens as different varieties or species when they may not have been.[6]:174 In this study, Wiegand compared characteristics among the specimens which had been largely ignored up to that point. Namely, "the exact length of the involucre and the inner involucral bracts, the number of rays, and the shape of the limb in the disk-corolla as well as the length and character of its lobes."[6]:162

Infraspecies

The Catalogue of Life (COL) recognized six infraspecies of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) Á.Löve & D.Löve on its 2009 Annual Checklist,[55] but by 2017, all had been demoted to taxonomic synonyms.[56] Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. hirsuticaule was demoted five years prior, in 2012.[57] According to Flora of North America, "[m]uch genetic and phenotypic variation is encountered within the complex; a thorough study is needed before a coherent taxonomy can be achieved."[5]

Although they are no longer accepted varieties according to COL,[3] they were accepted as of February 2021 by one or more of USDA PLANTS Database,[1] NatureServe,[9] World Flora Online (WFO),[58] Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS),[59] and Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN).[60] The autonym is Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. lateriflorum.[61]

Variety angustifolium

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. angustifolium (Wiegand) G.L.Nesom is commonly known as narrow-leaved calico aster and aster à feuilles étroites (French).[62] Latin angustus means narrow and folium means foliage or leaves.

_cropped.jpg.webp)

In 1903, American botanist, Edward Sandford Burgess described a new species he named Aster agrostifolius which, in addition to other characteristics, had very thin grass-like leaves.[33]:1226 Latin agrostis means grass. Wiegand, in 1928, then described a new variety of Aster lateriflorus with narrow lanceolate or linear leaves which he called Aster lateriflorus var. angustifolius. He did not associate it with Aster agrostifolius. Wiegand identified the holotype for this variety collected from Cheshire, Massachusetts, 1915, J. R. Churchill[lower-alpha 10] and held in the herbarium of the New England Botanical Club.[lower-alpha 11][6]:174 He was quick to note that "var. angustifolius may be nothing more than a separation of the narrow leaved individuals of the typical form."[6]:175 After Nesom reclassified the varieties from genus Aster to Symphyotrichum, Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. angustifolium was created, and the two former taxa became its synonyms.[64][54]:285

Variety flagellare

In 1953, Canadian-American botanist Lloyd Herbert Shinners named specimens as two new varieties of Aster lateriflorus: A. lateriflorus var. flagellaris Shinners and A. lateriflorus var. indutus Shinners.[65][66] In his protologues, Shinners said specifically that both had deeply lobed disk corollas and no rhizomes, and these characteristics were his reasoning for placing them both with A. lateriflorus.[67]:157–158

Regarding leaf characteristics, Shinners stated that Aster lateriflorus var. lateriflorus, A. l. var. angustifolius, and A. l. var. pendulus all had pubescent abaxial midribs, but did not say that his two new varieties had the same.[67]:157–158 He actually said the opposite: in the protologue for A. lateriflorus var. flagellaris, Shinners wrote in Latin "foliis subter omnino glabris," which in English is "leaves totally glabrous on the abaxial side."[67]:157 Thus, no hair abaxially on the leaves of this variety. In the A. lateriflorus var. indutus protologue, Shinners wrote "foliis subter puberulis super dense scabris," translated to English is "leaves with some hairs on the abaxial side, on the adaxial side densely scabrous." There is no mention of an exclusivity of hair on its midrib either.[67]:158

The type specimens of Aster lateriflorus var. flagellaris and A. l. var. indutus were both collected in Texas, the former in 1947 in Henderson County, and the latter in 1946, two miles southeast of Daingerfield, which is in Morris County. Shinners was working from only the type specimen for A. l. var. indutus, and he viewed multiple specimens for A. l. var. flagellaris, mostly from Texas, with one from McCurtain County, Oklahoma, which is the southeasternmost county of that state and on the north side of the Red River of the South bordering Texas.[67]:157–158

Specimens collected by American botanist Alfred Traverse in Harris County, Texas, and verified by Shinners as A. lateriflorus var. flagellaris are stored at the Botanical Research Institute of Texas Philecology Herbarium,[69][68] as is one collected by American botanist Eula Whitehouse at the Ottine wetlands in Gonzales County, Texas, in 1934, and determined by German-American botanist Almut Gitter Jones to be A. lateriflorus var. indutus.[70]

The current name of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. flagellare (Shinners) G.L.Nesom was created in 1995, and the two prior taxa became its synonyms.[71]

Variety hirsuticaule

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. hirsuticaule (Lindl. ex DC.) G.L.Nesom is known as rough-stemmed calico aster, starved aster, and aster latériflore à tiges hirsutes (French). Aster hirsuticaulis, its basionym, was originally published by Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle in 1836 as having been defined by English botanist John Lindley.[72] Latin hirsuti caulis translates to hairy stem. An abundance of flower cluster stem hair ("caule racemoso hirsutissimo") and the existence of abaxial leaf rib hair ("costâ subtùs hirsutissimâ") were both in the Latin protologue published by de Candolle.[73]

Subsequent authorities demoted Aster hirsuticaulis to infraspecies. American botanists John Torrey and Asa Gray did so first in 1841 with Aster miser var. hirsuticaulis,[74] using the abaxial pubescent or hirsute midrib as a primary defining factor.[75] They also stated that the leaves of the variety were "more or less hirsute."[75] Gray followed up in 1884 with Aster diffusus var. hirsuticaulis.[76] Here, Gray specified an environmental factor, "probably growing in much shade," also writing that the abaxial midrib and the stem were "very hirsute."[77]:187

In 1894, German botanist and horticulturist Andreas Voss further demoted Aster hirsuticaulis to a form of Aster diffusus.[78] Voss placed his form classifications of Aster hirsuticaulis and Aster bifrons under Aster diffusus var. thyrsoideus. He stated that these forms "sind nur üppige, an įchattigen und feuchten Orten stehende, loferer gebaute, höhere Bslangzen," in English, "are just luxurious plants growing at shady and moist places, less branched and taller."[79] That same year, Pennsylvania botanist Thomas Conrad Porter demoted Aster hirsuticaulis to a variety of Britton's Aster lateriflorus,[80] which took precedence.[81] Again, after Nesom reclassified the varieties from genus Aster to Symphyotrichum,[54]:285 these became synonyms of the new Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. hirsuticaule.[82]

Variety horizontale

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. horizontale (Desf.) G.L.Nesom is commonly called horizontal calico aster.[84] It has been in cultivation in Europe since the time of Linnaeus, and possibly prior. The protologue for the earliest synonym, Aster pendulus, was by William Aiton in 1789 who stated that the plant he was describing was cultivated in 1758 by English botanist Philip Miller[10]:204 who was chief gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden from 1722 to 1770.[85] In the preface of Hortus Kewensis, Aiton wrote that he remembered "several Plants to have been cultivated by Mr. Ph. Miller, in the Physick Garden at Chelsea, though no reference is made to them in [Miller's] Gardener's Dictionary."[86]:x

Nuttall demoted A. pendulus to a variety of A. divergens in 1818.[50]:159 In 1833, Lewis Caleb Beck created Aster miser var. pendulus from A. pendulus Aiton. His short description states simply that the leaves of the branches are "rather remote."[87]:186

In 1829, French botanist René Louiche Desfontaines described and named Aster horizontalis with a focus on ramuli horizontales, or horizontal branches.[88]:402 In 1884, Asa Gray placed this as a variety of Aster diffusus. His description included that it was a "cultivated form ... a plant of the gardens, not exactly matched by indigenous specimens, but evidently of this species." He gave the synonyms as A. horizontalis Desf. and A. recurvatus Willd., the latter previously described by German botanist Carl Ludwig Willdenow in 1803.[89]:2047

American botanist Oliver Atkins Farwell placed A. horizontalis Desf. as a variety of Aster lateriflorus (L.) Britton describing it in 1895 as "a tall plant with long straggling horizontal branches."[90]:21 In 1898, Burgess demoted Aster pendulus Aiton to a variety of A. lateriflorus.[91]:380

Nesom created Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. horizontale when he moved the varieties to genus Symphyotrichum.[92][54]:285 Its taxonomic synonyms are listed as Aster horizontalis Desf., Aster diffusus var. horizontalis (Desf.) A.Gray, Aster lateriflorus var. horizontalis (Desf.) Farw., and Aster lateriflorus var. pendulus (Aiton) E.S.Burgess.[93]

This variety is cultivated and marketed as an ornamental garden plant in Europe and gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit for value as such in 1993.[94]

Variety spatelliforme

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. spatelliforme (E.S.Burgess) G.L.Nesom was described by Burgess in 1903 as species Aster spatelliformis, making it the basionym of this variety. Burgess' protologue primarily focused on leaf characteristics which he said were how it differed from Aster lateriflorus. Leaves were described, in part, as small, rounded, and spatulate-shaped, with fine, reticulate veins and a short wedge-shaped base.[33]:1225

In 1984, Almut Gitter Jones demoted Aster spatelliformis to a variety of A. lateriflorus.[96]:379 Note that it was in 1982 that Löve and Löve began moving species to the genus Symphyotrichum.[53]:358–359 Two years prior, in 1980, Jones had placed Symphyotrichum as a subgenus of Aster.[97]:234 It was not until Nesom's evaluation of Aster sensu lato in 1995 that Jones' subgenus was combined with the genus.[54]:267 After this, Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. spatelliforme was created, and the two former taxa became its synonyms.[98]

Variety tenuipes

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. tenuipes (Wiegand) G.L.Nesom is commonly called slender-stalked calico aster and aster à pédoncule mince (French).[99] It was said by botanists Gleason and Cronquist to be a lax plant, with wiry stems, often larger heads in open panicles, and involucres to 6.5 mm.[100]

Wiegand first described it as a variety in 1928, Aster lateriflorus var. tenuipes Wiegand, with slender and "somewhat zigzag" stems, larger heads, and longer rays than the standard form of the species. He attached as type a specimen from Dundee, Prince Edward Island, collected in 1912 by Fernald, Long & St. John,[lower-alpha 12] stored as no. 814 in the Gray Herbarium.[lower-alpha 13][6]:174

In 1943, Shinners promoted it to species level as Aster tenuipes (Wiegand) Shinners, specifying that it lacked the "pubescent midveins" of A. lateriflorus.[101] This, however, was a name already in use since 1898 as Aster tenuipes Makino, native to Japan.[102][103] The following year, Shinners renamed his to Aster acadiensis Shinners.[104]

Nesom created Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. tenuipes when he moved the varieties to genus Symphyotrichum.[105][54]:285 These three names, Aster lateriflorus var. tenuipes Wiegand, Aster tenuipes (Wiegand) Shinners, and Aster acadiensis Shinners, are now its synonyms.[106]

Hybrids

The following naturally-occurring hybrids have been reported:

- Symphyotrichum lanceolatum subsp. lanceolatum × Symphyotrichum lateriflorum[107][108]

- Symphyotrichum laeve var. laeve × Symphyotrichum lateriflorum[109][110]

- Symphyotrichum dumosum × Symphyotrichum lateriflorum[17]

- Symphyotrichum lateriflorum × Symphyotrichum puniceum[17]

Distribution and habitat

Native

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is present in the wild in the United States in all states east of the Mississippi River; in the states on the west Mississippi River bank (Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana); and, in the western states of South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. It is also present in the Canadian provinces of Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. In Mexico, it is present in the state of Veracruz. Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is native throughout its current North American range.[2]

The USDA PLANTS Database, in addition, records a presence in British Columbia.[1] However, Flora of North America states that it was an ephemeral there that did not persist.[5]

Varietal distributions:

- S. lateriflorum var. angustifolium: present in Ontario, as well as the U.S. region of New England except Rhode Island, and in the states of Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and Wisconsin.[111]

- S. lateriflorum var. flagellare: present in Oklahoma and Texas.[112]

- S. lateriflorum var. hirsuticaule: present in Ontario, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick.[113] Because it is considered a synonym and not a variety of the species in most databases, United States distribution data cannot be found.

- S. lateriflorum var. horizontale: present in all U.S. states east of the Mississippi River excluding Indiana, Ohio, Virginia, South Carolina, and Louisiana. Also present west of the Mississippi in Minnesota, Missouri, and Arkansas.[114]

- S. lateriflorum var. spatelliforme: present in Florida.[115]

- S. lateriflorum var. tenuipes: present in Nova Scotia, Quebec, Prince Edward Island, Maine, Michigan, New Hampshire, New York, and Vermont.[116]

Introduced

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is an introduced species in Belgium,[117] France, Italy, and Switzerland.[2] It is not on the European Union's List of invasive alien species of Union concern.[118]

Habitat

Habitat can vary considerably, including wet to dry-mesic woodlands and savannas, floodplain woodlands, fens, marshes, wet to wet-mesic prairies, and high water table old fields.[7] Symphyotrichum lateriflorum has been found on banks, in thickets, and on shores usually in rather dry, but also in damp or even wet, sandy or gravelly soil.[6]:173

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is categorized on the United States National Wetland Plant List (NWPL) with Wetland Indicator Status Ratings of Facultative Wetland (FACW) and Facultative (FAC), depending on wetland region. In the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain (AGCP) and Northcentral and Northeast (NCNE) regions, it is a Facultative Plant (FAC), choosing wetlands or non-wetlands and adjusting accordingly. In the Eastern Mountains and Piedmont (EMP), Great Plains (GP), and Midwest (MW) regions, it is a Facultative Wetland Plant (FACW), usually occurring in wetlands, but not out of necessity. In these regions, it is less likely to, but may choose non-wetlands.[119]:176

Companions or associates depend upon the environment where Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is growing. Nearby naturally-occurring native North American trees can include silver maple (Acer saccharinum), ash-leaved maple or boxelder (Acer negundo), common hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), downy hawthorn (Crataegus mollis), the critically endangered green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), common elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), and the endangered American elm (Ulmus americana).[7]

Some companion Symphyotrichum species are Drummond's aster (S. drummondii), shining aster (S. firmum), panicled aster (S. lanceolatum), New England aster (S. novae-angliae), and purplestem aster (S. puniceum).[7]

Ecology

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is considered a weed species in Canada and the United States, but, say Chmielewski and Semple, "probably the least weedy of the weedy aster species in Canada." It is not considered a noxious weed in either country.[8]:838,839 S. lateriflorum has coefficients of conservatism (C-value) in the Floristic Quality Assessment (FQA) that range from 1 to 10 depending on evaluation region.[120] The lower the C-value, the higher tolerance the species has for disturbance and the lesser the likelihood that it is growing in a pre-settlement natural community.[121]:3 In the Dakotas, for example, S. lateriflorum has a C-value of 10, meaning its populations there are not at all weedy and are restricted to remnant natural areas with a very low tolerance to environmental degradation.[122] In contrast, in the Atlantic coastal pine barrens of Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island, S. lateriflorum has been given a C-value of 1, meaning its presence in locations of that ecoregion provides little or no confidence of a remnant habitat.[123]

Reproduction

The ray florets of species in the Symphyotrichum genus are exclusively female, each having a pistil but no stamen,[27] and are likely receptive to pollen longer than disk florets.[8]:842 Disk florets are bisexual, each with both male and female reproductive parts.[27] An adaptive mechanism of S. lateriflorum is its flower heads "go to sleep" at night. The flower heads close the ray florets around the disk florets. It has been surmised that this is to protect and preserve the pollen within[8]:842 and to prevent or reduce nectar evaporation at night.[124] Asteraceae ovaries are called inferior because each has only one ovule and can therefore produce only one seed.[lower-alpha 14]

Pollination occurs biotically with the help of short or mid-length tongued insects that are able to manipulate the small flower heads successfully and transfer pollen from one plant to another, known as cross-pollination. Studies have shown that any occasional self-pollination produces only a few viable seeds; thus, Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is an obligate (biologically required) outbreeder.[8]:842–843

Inside the disk corolla is the pollen-producing stamen whose filaments are fused to the corolla. The 5 anthers are fused together to form a cylinder, or tube, with their pollen on the inside only. This anther cylinder surrounds the stigma with style at the tip. The style has two lobes, or pieces, that are initially fused together making the ovary inaccessible. As the stigma is maturing, it elongates up through the anther cylinder, gathering the pollen on the style along the way.[125][124]:diagrams

At the bottom of the stigma is the disk floret ovary. The disk floret's stigma remains closed while pollen remains on the style, but after it has been collected and carried off, the style begins to split, opening so that the disk floret ovary becomes accessible to receive pollen from another plant. Pollination of the ray floret is similar, but there is no stamen with filament or anthers that require pollen collection.[125][124]:diagrams Seeds are ripe 3–4 weeks after pollination and are then wind dispersed, the ray floret seeds usually with ray attached, and disk floret seeds with corolla still attached.[8]:842–843

Reproduction also can occur through cloning via the plant's short rhizomatic structure. Typically, this causes the formation of small groups rather than large colonies, as Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is not a large colony-producing species. It is more likely that any vegetative reproduction (non-seed reproduction) forms within a clump.[8]:843

Pollinators and nectar-seekers

_2100x2100.jpg.webp)

Pollinators and nectar-seekers include short and mid-length tongued insects such as common eastern bumblebee (Bombus impatiens), European honeybee (Apis mellifera), eastern yellowjacket (Vespula maculifrons), bald-faced hornet (Dolichovespula maculata), cloudy-winged miner bee (Andrena nubecula), the miner bees Pseudopanurgus andrenoides and Pseudopanurgus compositarum, and the apoid wasp Cerceris kennicottii.[7]

Sweat bees and hoverflies also visit the flowers. Some that have been recorded include the bristle sweat bee (Lasioglossum imitatum), Cresson's metallic sweat bee (Lasioglossum cressonii), experienced sweat bee (Lasioglossum versatum), golden green sweat bee (Augochlorella aurata), leathery sweat bee (Lasioglossum coriaceum), nightmare sweat bee (Lasioglossum ephialtum), and pure golden green sweat bee (Augochlora pura). The hoverfly species Eristalis arbustorum, Eristalis dimidiata, and the calligrapher fly (Toxomerus marginatus) also have been recorded visiting the flowers.[7]

Pests and diseases

Banded woolly bear caterpillars, the larvae of the isabella tiger moth (Pyrrharctia isabella), eat the leaves.[7] Leaf miners, including the leaf blotch miner Acrocercops astericola[126] and the "trumpet" leaf miner Astrotischeria astericola, also eat the leaves.[127] The larvae of the Coleophora silk case-bearing moth Coleophora dextrella feed on the seeds,[128][129] and the galls produced by the midge Rhopalomyia lateriflori occur in the axillary buds where their larvae can develop.[8]:846

Fungal diseases include the rusts Puccinia dioicae and Puccinia asteris, which can occur on the leaves,[7] and the powdery mildew Erysiphe cichoracearum has been found on plants of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum in Ontario and Quebec.[8]:846

Conservation

NatureServe lists Symphyotrichum lateriflorum as Secure (G5) worldwide and Critically Imperiled (S1) in Kansas and Nebraska.[9][61] S. lateriflorum var. angustifolium is possibly Imperiled (S2) in Kentucky,[111] and S. lateriflorum var. horizontale is Imperiled (S2) in New Jersey.[114]

Uses

Ethnobotany

In 1928, ethnobotanist Huron Herbert Smith documented the Meskwaki use of this plant as a psychological aid using the "blossoms as a smudge 'to cure a crazy person who has lost his mind,'" and as an herbal steam using the entire plant "as a smoke or steam in sweatbath." The Meskwaki word is no'sîkûn, and the Potawatomi pûkwänä'sîkûn. Both words mean "smoke a person."[14] In her 1979 book Use of plants for the past 500 years, Charlotte Erichsen-Brown documented that the Mohawk people use an infusion of this plant with Symphyotrichum novae-angliae to treat fever.[8]:839

Ecological restoration

North American native wildflower or ecological restoration-focused companies may sell seeds or rootstock of non-cultivar Symphyotrichum lateriflorum for gardens and native landscape restoration.[130][131][132]

Gardening

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum is said to be hardy to USDA Zone 3 (to −40 °C (−40 °F)). It can be germinated from seed by sowing in a warm sunny location or by letting the seeds be dormant over the winter in the desired garden bed.[130] An adult plant can be propagated by division of the rootstock, although this is only needed every few years.[133]:102 It will grow well in shade or sun, and in any soil with some moisture. Spacing should be maintained between 45 and 90 centimeters (18 and 35 inches) at adult size.[130]

The earliest record of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum in gardens was of a synonym of S. lateriflorum var. horizontale called Aster pendulus. It was cultivated by an English botanist named Philip Miller by 1758.[10]:204 Miller was chief gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden in Chelsea, London, from 1722 to 1770.[85] A physic garden is one devoted to medicinal plants. This variety is still often called Aster lateriflorus var. horizontalis and is sometimes labeled in cultivar form as 'Horizontalis'.[84] London's Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) presents an Award of Garden Merit as a "seal of approval that the plant performs reliably in the garden."[134] S. lateriflorum var. horizontale gained this award for value as an ornamental garden plant in 1993.[94]

Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. horizontale is listed as very hardy with RHS Hardiness Rating H7, which is to below −20 °C (−4 °F).[94] The RHS Plant Finder suggests it for flower borders and beds of cottage and informal gardens, growing in an open location with full sun and well-drained moderately-fertile soil.[84]

Marketed cultivars of calico aster can be found using common names, the current and previous scientific names, as well as a misspelling of either as Aster laterifolius or Symphyotrichum laterifolium. Below is an alphabetical list of some probable or definite cultivars of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum with descriptions and history when available.

- 'Bleke Bet'[11] is said to reach a height of 120 cm (47 in), have dark leaves, and 18 mm (7⁄10 in) diameter flowers with rose to purple centers with white ray florets.[135][133]:103 In nursery catalog photographs, the ray florets appear to have a hint of pink,[136][137] and one nursery describes them as maturing with "soft pink shades."[135] Suggested uses include cut flowers and bee and butterfly friendly gardens.[137] In Dutch, bleke means pale, and some nursery websites have Pale Bess as an alternate name, although not in cultivar notation.[136][137] It blooms September–October and is hardy to USDA Zone 4, which is to −34.4 °C (−30 °F).[135] The best growing conditions are said to be in locations with full sun and moist yet well-drained soil.[137]

- 'Buck's Fizz'[138] is described as having numerous 13 mm (1⁄2 in) diameter white or light pink flowers with yellow then raspberry disks that bloom in September–October. Lanceolate leaves are dark green or maroon, and the cultivar reaches a maximum height of 50 cm (20 in).[139][140][133]:103 It is recommended for a sunny location with fertile soil and should be divided every few years.[133]:103

- 'Cassiope' is listed as a cultivar of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. lateriflorum and is without description in the RHS Plant Finder as of February 2021.[141] According to Paul Picton, it was introduced as early as 1910 as a cultivar of Aster vimineus.[133]:144

- 'Chaevis Callsope', last listed in the 2000 RHS Plant Finder, is without description as of February 2021.[142]

- 'Chloe'[143] has flowers that are described as small and pinkish-white in color with a darker pink center, and is recommended as a cut flower and to attract bees and butterflies.

'Chloe' in full bloom.

'Chloe' in full bloom.Photographs of 'Chloe' show it with longer ray florets than a standard calico aster. Dimensions can reach 60–150 cm (24–59 in) high by 45 cm (18 in) wide.[18][144][145] 'Chloe' is said to do best in full sun, neutral and semi-moist soil, in an open location.[145]

- 'Coombe Fishacre', found in the RHS Plant Finder simply as Symphyotrichum 'Coombe Fishacre' without a species name, won the RHS Award of Garden Merit in 1993.

A coombe or combe is a valley without a water course running through it. Combe Fishacre is a village in the English county of Devon with Coleton Fishacre, a 24-acre (97,000 m2) house and garden, on location. 'Coombe Fishacre', the cultivar, has multiple common or marketing synonyms and is offered both as a cultivar of Aster novi-belgii (Symphyotrichum novi-belgii, New York Aster) and A. lateriflorus (S. lateriflorum),[146] and even as a hybrid of both.[147] RHS shows another synonym, Aster coelestis 'Coombe Fishacre'.[146] A. diffusus var. horizontalis was its parent according to the following passage from the periodical Gardening World Illustrated (1898).[20] That variety is the Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. horizontale of today.

The comparatively new variety [of Michaelmas Daisy], Coombe Fishacre, which was raised by Mr. Archer Hind, is in magnificent condition at Long Ditton at the present time, and the plants are conspicuous amongst all the rest by reason of their extreme floriferousness. The bronzy-red and white flowers much resemble those of A. diffusus horizontalis, its parent, but they are larger and finer. The height is about 31/2 ft. As a vase-filling plant there is nothing to beat this variety, for the stems are well clothed with long, lateral branches, all full of flower, so that a single stem in a vase presents a perfect pyramid of bloom. If a selection had to be made of a dozen forms, this should certainly be one of them.[20]

.jpg.webp) 'Coombe Fishacre' in a garden in England.

'Coombe Fishacre' in a garden in England.'Coombe Fishacre' is described in modern catalogs as spreading and bushy "with neat, dark foliage" and flower heads with lilac-pink rays and brownish-pink disks. The cultivar is said to be hardy to RHS H7, bloom in late summer and autumn, and in 2–5 years reach a height of 50–100 cm (20–39 in) and width of 10–50 cm (4–20 in).[146] The availability of 'Coombe Fishacre' is widespread, from the U.K. to mainland Europe to New Zealand.[148][149][150][151][152] It is said to grow well in full sun with moderately-moist soil of any type, but may be negatively affected by windy conditions.[151]

- 'Daisy Bush' was introduced in 1993 and has green leaves and bushy branches of flower heads that are 2 cm (4⁄5 in) diameter, with white rays and pale yellow disks. It reaches a height of 70 cm (28 in).[133]:103 It was last listed in the RHS Plant Finder in 1997.[153]

- 'Datschi' was last listed in the RHS Plant Finder in 2018.[154] According to Picton, 'Datschi' was introduced before 1920. He described it with flower heads 13 mm (1⁄2 in) diameter, white rays, pale yellow disk florets that are less likely to change color, with deep green leaves and a height of 120 cm (47 in).[133]:103 There was a cultivar named Datschi in the RHS Autumn 1919 trials at Wisely assigned to their type diffusus,[155]:371 which is not explicitly said to be an Aster diffusus cultivar but is more descriptive of that growing habit.[155]:370 It had single white flowers reported as 3⁄8–1⁄2 inch diameter that bloomed from 23 October 1919–5 November 1919, and it reached a height of 4 feet.[155]:371

In a French online catalog, an Aster datschii (ending in ii) is described as "touffe buissonnante vigoureuse" ("vigorous bushy tuft") with dark green leaves and numerous white flowers of medium size that bloom October–November. It reaches a mature height and width of 80 cm (31 in) and 40 cm (16 in), respectively, and is hardy to −15 °C (5 °F).[156] It is recommended for a sunny location with fertile soil.[133]:103

- 'Delight' was last listed in the RHS Plant Finder in 2007.[157] An old cultivar, this compact plant was introduced before 1902. The flower heads are 13 mm (1⁄2 in) diameter with white reflexed rays and creamy-yellow disks, and it reaches a height of 90 cm (35 in). It is recommended for a sunny location with fertile soil.[133]:103

- 'Golden Rain' is listed as a cultivar of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. lateriflorum and is without description in the RHS Plant Finder as of February 2021.[158] Picton lists it as a cultivar of Aster vimineus "with creamy-white ray florets and deep yellow disks" that was introduced around 1910 by H.J. Jones from his Lewisham nursery. It reaches a height of only 45 cm (18 in).[133]:144

- 'Jan',[159] introduced in 1992, has large flower heads for a cultivar of this species at 3 cm (11⁄5 in) diameter.[133]:104 Reaching heights of 76 cm (30 in), it has green leaves with white and lilac blooms,[160] or white ray florets with red-brown centers.[161] 'Jan' is suggested for an open sunny and warm location with fertile and moist soil. It is said to be hardy to −30 °C (−22 °F) but also requires protection from rain and snow in the winter.[160]

- 'Lady in Black' is a cultivar from the Netherlands[162] introduced in 1991.[133]:104 It has bronze and dark purple leaves with flowers that have white rays and "rosy-pink" centers.

'Lady in Black' at Behnke Nurseries, Beltsville, Maryland.

'Lady in Black' at Behnke Nurseries, Beltsville, Maryland.Bushy and shrub-like, it reaches a height of 100–150 cm (39–59 in) and width of 50–100 cm (20–39 in) in 2–5 years. 'Lady in Black' is hardy to RHS H7[12] and USDA Zone 4.[163] The RHS Plant Finder suggests it for flower borders and beds of cottage and informal gardens, growing in any location with sun and well-drained moderately-fertile soil.[12] The availability of 'Lady in Black' is widespread, from the U.K. and mainland Europe to Canada and the United States.[163][23][164][165]

- 'Lovely'[166] is described as having pink or pinkish-purple flowers, green lanceolate leaves, with a height of 50–100 cm (20–39 in) and width of 30–50 cm (12–20 in).[167][168] Hardy to USDA Zone 3,[169] it blooms August–October and thrives in full sun.[167][168]

'Lovely' can be found listed as a cultivar of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum[166][167] (Aster lateriflorus[24]) and Aster vimineus.[170] The heritage is unclear, and it could have S. lateriflorum or S. racemosum as its primary parentage (S. racemosum is the current name for A. vimineus). A Symphyotrichum ericoides 'Lovely' (as Aster ericoides) can be found on one website which provides the information "for reference only."[169]

- Nineteen is from one garden catalog without cultivar notation and said to be from a 'Bleke Bet' seedling. Flowers are lilac with rose centers and larger than the base calico aster. It has dark foliage that turns red and can reach a height of 120 cm (47 in). It blooms September–November and is hardy to RHS H7.[171]

- 'Orphir' is listed as a cultivar of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. lateriflorum and is without description in the RHS Plant Finder as of February 2021.[172] Picton lists it as a cultivar of Aster vimineus dating to as early as 1910.[133]:144

- 'Prince',[13] introduced circa 1970,[133]:104 is available from multiple vendors in the U.K., mainland Europe, and United States.[173][174][175][176][177][178] This cultivar is compact and after 2–5 years, will remain at a height of 30–60 cm (12–24 in) and width about the same.[173] It prefers full sun and needs room to spread so there is no competition at the roots with nearby plants.[178][179] 'Prince' has dark purple foliage, and its 13 mm (1⁄2 in) diameter flower heads[133]:104 have white rays with large deep pink-colored centers.[179] It is recommended for cut flowers and attracts bees and butterflies.[173][180] Hardy to USDA Zone 4,[176] 'Prince' blooms August–November, depending on location.[175][177] It is said to do best in sun with average soil.[177]

- 'Prince Charming' is listed as a cultivar of Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. lateriflorum and is without description in the RHS Plant Finder as of February 2021.[181] Picton lists 'Prince Charming' as a cultivar of Aster vimineus dating to as early as 1910.[133]:144

- 'Rubrifolius' was last listed in the 2001 RHS Plant Finder.[182] Translated from Latin, rubri folium means red leaf or red foliage, but other than the name, no information was readily available about this cultivar as of January 2021.

- 'Valentin' is described with white-pale lilac flowers that bloom September–November, with an adult height of about 76 cm (30 in). It is hardy to −30 °C (−22 °F) and is said to do best in an open sunny location with well-drained moderately-fertile moist soil.[22]

- 'White Lovely' is described as having horizontal and arching branches, purple-streaked stems, narrow dark green leaves, and small "white daisies" tinged lilac with yellow disks that appear August–October. Dimensions can reach about 76 cm (30 in) high by 76 cm (30 in) wide.[183] Hardy to USDA Zone 4, 'White Lovely' attracts bees, butterflies, and other pollinators. It is said to grow well in full sun or partial shade, and various soil with at least some moisture.[184]

Notes

- Repeated branching of the veins on the leaf so that they look like a net.

- Outside ranges 3 cm (1.2 in) to 15 cm (6 in) and 2 mm to 3.5 cm (1.4 in), respectively.[5]

- See Asteracae § Flowers for more detail.

- Outside range 3.5–7 mm.[5]

- Outside range about 6–25.[17]

- Outside range about 6–20.[17][5]

- All species in the Symphyotrichum genus have disk florets that mature to a pink, purple, or light brown. This is not unique to calico aster.[27]

- There are 5 lobes on the disk florets of all species in Symphyotrichum genus.[27]

- Aiton was excluding a species named Aster ericoides Meliloti agrariae umbone and drawn by German botanist Johann Jacob Dillenius in his 1732 Hortus Elthamensis. Linnaeus referenced it as the species he named Aster miser. See [46]:877 and [49] for details.

- Joseph Richmond Churchill of Dorchester, Massachusetts.[63]

- Information about and image of this holotype is viewable online at the Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries Digital Collections (huh.harvard.edu) — Specimens, [Barcode 00263144].

- Merritt Lyndon Fernald, Bayard Henry Long, and Harold St. John.

- Information about this holotype (without image) is viewable online at the Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries Digital Collections (huh.harvard.edu) — Specimens, [Barcode 00936398].

- See also Asteraceae § Floral structures and Gynoecium.

References

- USDA, NRCS (2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum". (plants.usda.gov). Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- POWO (2019). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) Á.Löve & D.Löve". Plants of the World Online (powo.science.kew.org). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- Hassler, M. (2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) A. Löve & D. Löve". World Plants: Synonymic Checklists of the Vascular Plants of the World (version Sep 2020). Retrieved 18 December 2020 – via Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life, 2020-12-01 (Roskov, Y.; Ower, G.; Orrell, T.; Nicolson, D.; Bailly, N.; Kirk, P.M.; Bourgoin, T.; DeWalt, R.E.; Decock, W.; van Nieukerken, E.J.; Penev, L.; eds.). Digital resource at Catalogue of Life (www.catalogueoflife.org). Species 2000: Naturalis, Leiden, the Netherlands. ISSN 2405-8858.

- GBIF Secretariat (2019). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) Á.Löve & D.Löve". Global Biodiversity Information Facility (gbif.org). Copenhagen: GBIF Secretariat. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 20. New York and Oxford. Retrieved 14 September 2020 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Wiegand, K.M. (1928). "Aster lateriflorus and some of its relatives". Rhodora. Providence, Rhode Island: Preston and Rounds Co. 30. ISSN 0035-4902. Retrieved 3 November 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Wilhelm, G.; Rericha, L. (2017). Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis. Illustrated by Lowther, M.M. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Academy of Science. pp. 1101–1102. ISBN 978-1883362157. OCLC 983207050.

- Chmielewski, J.G.; Semple, J.C. (2001). "The biology of Canadian weeds. 113. Symphyotrichum lanceolatum (Willd.) Nesom [Aster lanceolatus Willd.] and S. lateriflorum (L.) Löve & Löve [Aster lateriflorus (L.) Britt.]". Canadian Journal of Plant Science. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Science Publishing. 81 (4): 829–849. doi:10.4141/P00-056. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- NatureServe (4 September 2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum - Starved Aster". NatureServe Explorer (explorer.natureserve.org). Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Aiton, W. (1789). Hortus Kewensis; or, a catalogue of the plants cultivated in the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew (in Latin). 3. London: George Nicol. Retrieved 21 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Royal Horticultural Society. "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum lateriflorum 'Bleke Bet'". Royal Horticultural Society (www.rhs.org.uk). London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Royal Horticultural Society. "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum lateriflorum 'Lady in Black'". Royal Horticultural Society (www.rhs.org.uk). London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Royal Horticultural Society. "RHS Plant Finder - Symphyotrichum lateriflorum 'Prince'". Royal Horticultural Society (www.rhs.org.uk). London: Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Smith, H.H. (1928). "Ethnobotany of the Meskwaki Indians". Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee (Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Pub. by order of the board of trustees of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee). 4: 212. Retrieved 3 November 2020 – via eHRAF World Cultures (New Haven, Conn.: Human Relations Area Files, 2014. Transcription and some images from original in online database. Analyzed by Eleanor Swanson and John Beierle, 1976).

- Missouri Botanical Garden (n.d.). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum - Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder". (MissouriBotanicalGarden.org). St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Chicago Botanic Garden (2021). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum — Side-flowering Aster". Chicago Botanic Garden (www.chicagobotanic.org). Glencoe, Illinois: Chicago Botanic Garden. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Native Plant Trust (2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (calico American-aster): Go Botany". Go Botany (GoBotany.NativePlantTrust.org). Framingham, Massachusetts: Native Plant Trust. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Hardy's Cottage Garden Plants (2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum 'Chloe'". Hardy's Cottage Garden Plants (www.hardysplants.co.uk). Hampshire, England: Priory Lane Nursery. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Fuchs, L. (1542). De historia stirpium commentarii insignes (in Latin). Illustrated by Meyer, A.; Füllmaurer, H.; and Speckle, V.R. Basel, Switzerland: In officina Isingriniana. p. 133. Retrieved 3 January 2021 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Fraser, J., ed. (22 October 1898). "Michaelmas Daisies at Long Ditton". The gardening world illustrated: a weekly paper exclusively devoted to all branches of practical gardening. Vol. 15. London: Brian Wynne. p. 123. Retrieved 3 January 2021 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Kridtvejs Planter (2021). "Aster lateriflorus Horizontalis / Asters / Sommerens Farvel". Kridtvejs Planter (kridtvejsplanter.dk) (in Danish). Vils, Morsø, Nordjylland, Denmark: Kridtvejs Planter. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- TUINSeizoen [Garden Season] (2021). "Aster lateriflorus 'Valentin'". TUINSeizoen (tuinseizoen.com) (in Dutch). Breda, Netherlands: VIPMEDIA Publishing & Services. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- Staudengärtnerei Kirschenlohr (2021). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum 'Lady In Black'". Staudengärtnerei Kirschenlohr (www.stauden-kirschenlohr.de) (in German). Speyer, Germany: Staudengärtnerei Kirschenlohr [Kirschenlohr Perennial Nursery]. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Mann, D. (2021). "Pflanzenportrat: Aster lateriflorus 'Lovely' – Waagerechte Aster" [Plant portrait: Aster lateriflorus 'Lovely' - Horizontal aster]. Pflanzen Reich: Botanische Sammlung & Gartenenzyklopädie [Plant Kingdom: Botanical Collection & Garden Encyclopedia] (www.pflanzenreich.com) (in German). Müglitztal, Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge, Saxony, Germany: Gartenjournalist.de. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Kondzio (27 September 2016). "TEMAT: Aster bocznokwiatowy (Aster lateriflorus) - odmiany i warunki uprawy w ogrodzie" [SUBJECT: Side flower aster (Aster lateriflorus) - varieties and growing conditions in the garden]. Zielono Zakręceni (zielonozakreceni.pl) (in Polish). Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Wester, H. (4 December 2015). "Grenaster - Symphyotrichum lateriflorum". Stockholms gröna rum (gardener.blogg.se) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Hasse Wester. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Brouillet, L.; Semple, J.C.; Allen, G.A.; Chambers, K.L.; Sundberg, S.D. (2006). "Symphyotrichum". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 20. New York and Oxford. Retrieved 4 November 2020 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) (n.d.). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var tenuipes (Wiegand) G.L.Nesom". TORCH: The Texas Oklahoma Regional Consortium of Herbaria (www.torcherbaria.org). Texas: TORCH. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) (n.d.). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var lateriflorum". TORCH: The Texas Oklahoma Regional Consortium of Herbaria (www.torcherbaria.org). Texas: TORCH. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) (n.d.). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var lateriflorum". TORCH: The Texas Oklahoma Regional Consortium of Herbaria (www.torcherbaria.org). Texas: TORCH. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) (n.d.). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) Á.Löve & D.Löve". TORCH: The Texas Oklahoma Regional Consortium of Herbaria (www.torcherbaria.org). Texas: TORCH. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- North Carolina Native Plant Society (2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (= Aster lateriflorus) Starved Aster, Calico Aster, Calico American-aster". (plants.ncwildflower.org). North Carolina Native Plant Society. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Small, J.K. (1903). Flora of the Southeastern United States, being descriptions of the seed-plants, ferns and fern-allies growing naturally in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana and the Indian territory and in Oklahoma and Texas east of the one-hundredth meridian. New York: Published by the author – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Hilty, J. (2018). "Calico Aster Symphyotrichum lateriflorum". Illinois Wildflowers (illinoiswildflowers.info). Illinois Wildflowers. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- Chayka, K.; Dziuk, P. (2016). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (Calico Aster): Minnesota Wildflowers". Minnesota Wildflowers (www.minnesotawildflowers.info). Archived from the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- Morhardt, S.; Morhardt, E. (2004). California desert flowers: an introductions to families, genera, and species. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0520240030.

- Barkley, T.M.; Brouillet, L.; Strother, J.L. (2006). "Asteraceae". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 19. New York and Oxford. Retrieved 10 January 2021 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Semple, J.C. (n.d.). "Symphyotrichum Dumosi: Bushy Asters and Relatives". University of Waterloo (UWaterloo.ca). Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Native Plant Trust (2020). "Symphyotrichum (American-aster): Go Botany". Go Botany (GoBotany.NativePlantTrust.org). Framingham, Massachusetts: Native Plant Trust. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) (2020). "Linnaeus, Carl (1707-1778)". IPNI (www.ipni.org). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) (2020). "Löve, Áskell (1916-1994)". IPNI (www.ipni.org). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) (2020). "Löve, Doris Benta Maria (1918-2000)". IPNI (www.ipni.org). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Turland, N.J.; Wiersema, J.H.; Barrie, F.R.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Kusber, W.-H.; Li, D.-Z.; Marhold, K.; May, T.W.; McNeill, J.; Monro, A.M.; Prado, J.; Price, M.J.; Smith, G.F., eds. (2018). CHAPTER VI: CITATION - SECTION 1: AUTHOR CITATIONS - ARTICLE 49. International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the Nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017. Regnum Vegetabile 159. Regnum Vegetabile. 159. Glashütten, Hesse, Germany: Koeltz Botanical Books. doi:10.12705/Code.2018. ISBN 9783946583165. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Semple, J.C. (2014). "Classification of Symphyotrichum in the restricted sense". University of Waterloo (UWaterloo.ca). Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- Kalm, P. (1770) [1753]. Travels into North America: containing its natural history, and a circumstantial account of its plantations and agriculture in general, with the civil, ecclesiastical and commercial state of the country, the manners of the inhabitants, and several curious and important remarks on various subjects. 1. Translated by Forster, J.R. (1st ed.). Warrington, England: William Eyres. p. x. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.27718. Retrieved 9 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Linnaeus, C. (1753). Species Plantarum: exhibentes plantas rite cognitas, ad genera relatas, cum differentiis specificis, nominibus trivialibus, synonymis selectis, locis natalibus, secundum systema sexuale digestas (in Latin). 2 (1st ed.). Stockholm: Impensis Laurentii Salvii. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.669. Retrieved 9 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- POWO (2019). "Accepted Solidago species search results". Plants of the World Online (powo.science.kew.org). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aiton, William". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 448.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aiton, William". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 448.

- Dillenius, J.J. (1732). Hortus Elthamensis, seu Plantarum rariorum, quas in horto suo Elthami in Cantio coluit vir ornatissimus et praestantissimus Jacobus Sherard M.D. Soc. Reg. et Coll. Med. Lond. Soc. Guilielmi P.M. Frater, delineationes et descriptiones quarum historia vel plane non, vel imperfecte a rei herbariae scriptoribus tradita fuit (in Latin). 1. Londini [London]: Sumptibus auctoris. Plate 40. Retrieved 21 December 2020 – via Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid, Biblioteca Digital (bibdigital.rjb.csic.es) [Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid, Digital Library].

- Nuttall, T. (1818). The genera of North American plants, and a catalogue of the species, to the year 1817. 2. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: D. Heartt. Retrieved 21 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Britton, N.L. (1889). "New or noteworthy North American phanerogams, II". Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences. New York: New York Academy of Sciences. 9: 1. ISSN 0028-7113. Retrieved 20 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Semple, J.C. (2019). "An overview of "asters" and the Tribe Astereae". University of Waterloo (UWaterloo.ca). Waterloo, Ontario: University of Waterloo. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Löve, Á. (1982). "IOPB Chromosome Number Reports LXXV". Taxon. Utrecht, Netherlands: The International Bureau for Plant Taxonomy and Nomenclature. 31 (2): 359. ISSN 0040-0262. JSTOR 1220008. Retrieved 9 December 2020 – via JSTOR.

- Nesom, G.L. (1995). "Review of the taxonomy of Aster sensu lato (Asteraceae: Astereae), emphasizing the New World species". Phytologia. Huntsville, Texas: Michael J. Warnock. 77 (3): 141–297. ISSN 0031-9430. Retrieved 24 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Bisby, F.A.; Roskov, Y.R.; Orrell, T.M.; Nicolson, D.; Paglinawan, L.E.; Bailly, N.; Kirk, P.M.; Bourgoin, T.; Baillargeon, G., eds. (2009). "Catalogue of Life : 2009 Annual Checklist : Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) A.& D. Löve". Catalogue of Life (www.catalogueoflife.org). ITIS. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Hassler, M. (2017). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) A. Löve & D. Löve". World Plants: Synonymic Checklists of the Vascular Plants of the World (version Feb 2017). Retrieved 18 December 2020 – via Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life, 2017 Annual Checklist (Roskov, Y.; Abucay, L.; Orrell, T.; Nicolson, D.; Bailly, N.; Kirk, P.M.; Bourgoin, T.; DeWalt, R.E.; Decock, W.; De Wever, A.; Nieukerken, E. van; Zarucchi, J.; Penev, L.; eds.). Digital resource at Catalogue of Life (www.catalogueoflife.org). Species 2000: Naturalis, Leiden, the Netherlands. ISSN 2405-884X.

- Bisby, F.; Roskov, Y.; Culham, A.; Orrell, T.; Nicolson, D.; Paglinawan, L.; Bailly, N.; Appeltans, W.; Kirk, P.; Bourgoin, T.; Baillargeon, G.; Ouvrard, D., eds. (2012). "Catalogue of Life : 2012 Annual Checklist : Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. hirsuticaule (DC.) Nesom". Catalogue of Life (www.catalogueoflife.org). ITIS. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- WFO (2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (L.) Á.Löve & D.Löve". (WorldFloraOnline.org). World Flora Online Consortium. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ITIS (2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum". ITIS (www.itis.gov). Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Brouillet, L.; Desmet, P.; Coursol, F.; Meades, S.J.; Favreau, M.; Anions, M.; Bélisle, P.; Gendreau, C.; Shorthouse, D. (4 September 2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum (Linnaeus) Á. Löve & D. Löve". (data.canadensys.net). Database of Vascular Plants of Canada (VASCAN). Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- NatureServe (4 September 2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. lateriflorum". NatureServe Explorer (explorer.natureserve.org). Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- GBIF Secretariat (2019). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. angustifolium (Wieg.) G.L.Nesom". Global Biodiversity Information Facility (gbif.org). Copenhagen: GBIF Secretariat. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

-

Churchill, J.R. (12 August 1912). Correspondence: Churchill, Joseph Richmond Aug. 12, 1912 to Walter Deane. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Herbarium of J. R. Churchill, No. 32 Percival Street, Dorchester, Mass.

- WFO (2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. angustifolium (Wiegand) G.L.Nesom". (WorldFloraOnline.org). World Flora Online Consortium. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) (2020). "Aster lateriflorus var. flagellaris Shinners, Field & Lab. 21: 157 (1953)". IPNI (www.ipni.org). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) (2020). "Aster lateriflorus var. indutus Shinners, Field & Lab. 21: 158 (1953)". IPNI (www.ipni.org). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Shinners, L.H. (1953). "Notes on Texas Compositae — IX". Field & Laboratory; Contributions from the Science Departments. University Park, Texas: Southern Methodist University . 21: 155–162. ISSN 0096-042X.

- Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) (2020). "BRIT560693: Aster lateriflorus var. flagellaris Shinners, herbarium specimen collected 1960-11-01". TORCH: The Texas Oklahoma Regional Consortium of Herbaria (www.torcherbaria.org). Texas: TORCH. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) (2020). "BRIT560692: Aster lateriflorus var. flagellaris Shinners, herbarium specimen collected 1956-10-25". TORCH: The Texas Oklahoma Regional Consortium of Herbaria (www.torcherbaria.org). Texas: TORCH. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) (2020). "BRIT333802: Aster lateriflorus var. indutus Shinners, herbarium specimen collected 1934-10-23". TORCH: The Texas Oklahoma Regional Consortium of Herbaria (www.torcherbaria.org). Texas: TORCH. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- WFO (2020). "Symphyotrichum lateriflorum var. flagellare (Shinners) G.L.Nesom". (WorldFloraOnline.org). World Flora Online Consortium. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) (2020). "Aster hirsuticaulis Lindl. ex DC., Prodr. [A. P. de Candolle] 5: 242 (1836)". IPNI (www.ipni.org). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- De Candolle, A.P. (1836). Prodromus systematis naturalis regni vegetabilis, sive enumeratio contracta ordinum, generum, specierumque plantarum huc usque cognitarum, juxta methodi naturalis normas digesta, Pars 5, Sistens Calycereas et Compositarum tribus priores (in Latin). Parisiis [Paris]: Treuttel et Würtz. p. 242. Retrieved 15 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) (2020). "Aster miser var. hirsuticaulis (Lindl. ex DC.) Torr. & A.Gray, Fl. N. Amer. (Torr. & A. Gray) 2(1): 131 (1841)". IPNI (www.ipni.org). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Torrey, J.; Gray, A. (1841). A flora of North America: containing abridged descriptions of all the known indigenous and naturalized plants growing north of Mexico, arranged according to the natural system. 2. New York: Wiley & Putnam. p. 131. Retrieved 16 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) (2020). "Aster diffusus var. hirsuticaulis (Lindl. ex DC. in DC.) A.Gray, Syn. Fl. N. Amer. 1, pt. 2: 187 (1884)". IPNI (www.ipni.org). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Gray, A. (1884). Synoptical Flora of North America. Vol. I. Part II. Caprifoliaceae – Compositae. New York: American Book Company. Retrieved 16 December 2020 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- International Plant Names Index (IPNI) (2020). "Aster diffusus f. hirsuticaulis (Lindl. ex DC.) Voss, Vilm. Blumengärtn., ed. 3. 1: 467 (1894)". IPNI (www.ipni.org). The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries; and, Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 19 December 2020.