Synthetism

Synthetism is a term used by post-Impressionist artists like Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard and Louis Anquetin to distinguish their work from Impressionism. Earlier, Synthetism has been connected to the term Cloisonnism, and later to Symbolism.[1] The term is derived from the French verb synthétiser (to synthesize or to combine so as to form a new, complex product).

Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, Louis Anquetin, and others pioneered the style during the late 1880s and early 1890s.

Synthetist artists aimed to synthesize three features:

- The outward appearance of natural forms.

- The artist's feelings about their subject.

- The purity of the aesthetic considerations of line, colour and form.

In 1890, Maurice Denis summarized the goals for synthetism as,

- It is well to remember that a picture before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.

The term was first used in 1877 to distinguish between scientific and naturalistic impressionism, and in 1889 when Gauguin and Emile Schuffenecker organized an Exposition de peintures du groupe impressioniste et synthétiste in the Café Volpini at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. The confusing title has been mistakenly associated with impressionism. Synthetism emphasized two-dimensional flat patterns, thus differing from impressionist art and theory.

Synthetist paintings

- Paul Sérusier - Talisman (Bois d'amour) (1888)

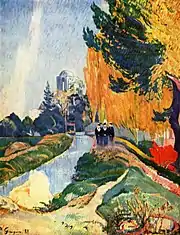

- Paul Gauguin - Vision After The Sermon (1888), La Belle Angele (1889), The Loss of Innocence (1890)

- Émile Bernard - Buckwheat Harvest (1888)

- Charles Laval - Going to Market (1888)

- Cuno Amiet - Breton Spinner (1893)

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

Paul Sérusier, The Talisman (with the forest landscape of love in Pont-Aven) 1888

Paul Sérusier, The Talisman (with the forest landscape of love in Pont-Aven) 1888

Paul Gauguin, The Green Christ, 1889

Paul Gauguin, The Green Christ, 1889.jpg.webp) Émile Bernard, Breton Women in the Meadow, August 1888. Bernard exchanged this one with Gauguin who brought it to Arles in autumn 1888 when he joined Van Gogh, who was fond of this style. Van Gogh painted a copy in watercolor to inform his brother Theo about it.

Émile Bernard, Breton Women in the Meadow, August 1888. Bernard exchanged this one with Gauguin who brought it to Arles in autumn 1888 when he joined Van Gogh, who was fond of this style. Van Gogh painted a copy in watercolor to inform his brother Theo about it. Vincent van Gogh, Breton Women and Children, November 1888 (watercolor after Bernard).

Vincent van Gogh, Breton Women and Children, November 1888 (watercolor after Bernard).

Louis Anquetin, Reading Woman, 1890

Louis Anquetin, Reading Woman, 1890

References

- Brettell, Richard R. (1999). Modern Art, 1851-1929: Capitalism and Representation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019284220X.

- Charles Laval Retrieved April 6, 2011