Animal sacrifice

Animal sacrifice is the ritual killing and offering of an animal, usually as part of a religious ritual or to appease or maintain favour with a deity. Animal sacrifices were common throughout Europe and the Ancient Near East until the spread of Christianity in Late Antiquity, and continue in some cultures or religions today. Human sacrifice, where it existed, was always much more rare.

All or only part of a sacrificial animal may be offered; some cultures, like the ancient and modern Greeks, eat most of the edible parts of the sacrifice in a feast, and burnt the rest as an offering. Others burnt the whole animal offering, called a holocaust. Usually the best animal or best share of the animal is the one presented for offering.

Animal sacrifice should generally be distinguished from the religiously-prescribed methods of ritual slaughter of animals for normal consumption as food.

.JPG.webp)

During the Neolithic Revolution, early humans began to move from hunter-gatherer cultures toward agriculture, leading to the spread of animal domestication. In a theory presented in Homo Necans, mythologist Walter Burkert suggests that the ritual sacrifice of livestock may have developed as a continuation of ancient hunting rituals, as livestock replaced wild game in the food supply.[1]

Prehistory

Ancient Egypt was at the forefront of domestication, and some of the earliest archeological evidence suggesting animal sacrifice comes from Egypt. The oldest Egyptian burial sites containing animal remains originate from the Badari culture of Upper Egypt, which flourished between 4400 and 4000 BC.[2] Sheep and goats were found buried in their own graves at one site, while at another site gazelles were found at the feet of several human burials.[2] At a cemetery uncovered at Hierakonpolis and dated to 3000 BC, the remains of a much wider variety of animals were found, including non-domestic species such as baboons and hippopotami, which may have been sacrificed in honor of powerful former citizens or buried near their former owners.[3] According to Herodotus, later Dynastic Egyptian animal sacrifice became restricted to livestock - sheep, cattle, swine and geese - with sets of rituals and rules to describe each type of sacrifice.[4]

By the end of Copper Age in 3000 BC, animal sacrifice had become a common practice across many cultures, and appeared to have become more generally restricted to domestic livestock. At Gath, archeological evidence indicates that the Canaanites imported sacrificial sheep and goats from Egypt rather than selecting from their own livestock.[5] At the Monte d'Accoddi in Sardinia, one of the earliest known sacred centers in Europe, evidence of the sacrifice of sheep, cattle and swine has been uncovered by excavations, and it is indicated that ritual sacrifice may have been common across Italy around 3000 BC and afterwards.[6] At the Minoan settlement of Phaistos in ancient Crete, excavations have revealed basins for animal sacrifice dating to the period 2000 to 1700 BC.[7] However, remains of a young goat were found in Cueva de la Dehesilla (es), a cave in Spain, related to a funerary ritual from the Middle Neolithic period, dated to between 4800 and 4000 BC.[8]

Ancient Near East

Animal sacrifice was general among the ancient Near Eastern civilizations of Ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia, as well as the Hebrews (covered below). Unlike the Greeks, who had worked out a justification for keeping the best edible parts of the sacrifice for the assembled humans to eat, in these cultures the whole animal was normally placed on the fire by the altar and burned, or sometimes it was buried.[9]

Ancient Greece

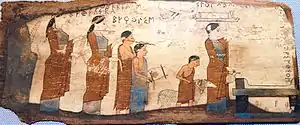

Worship in ancient Greek religion typically consisted of sacrificing domestic animals at the altar with hymn and prayer. The altar was outside any temple building, and might not be associated with a temple at all. The animal, which should be perfect of its kind, is decorated with garlands and the like, and led in procession to the altar, a girl with a basket on her head containing the concealed knife leading the way. After various rituals the animal is slaughtered over the altar, as it falls all the women present "must cry out in high, shrill tones". Its blood is collected and poured over the altar. It is butchered on the spot and various internal organs, bones and other inedible parts burnt as the deity's portion of the offering, while the meat is removed to be prepared for the participants to eat; the leading figures tasting it on the spot. The temple usually kept the skin, to sell to tanners. That the humans got more use from the sacrifice than the deity had not escaped the Greeks, and is often the subject of humour in Greek comedy.[10]

The animals used are, in order of preference, bull or ox, cow, sheep (the most common), goat, pig (with piglet the cheapest mammal), and poultry (but rarely other birds or fish).[11] Horses and asses are seen on some vases in the Geometric style (900-750 BC), but are very rarely mentioned in literature; they were relatively late introductions to Greece, and it has been suggested that Greek preferences in this matter go very far back. The Greeks liked to believe that the animal was glad to be sacrificed, and interpreted various behaviours as showing this. Divination by examining parts of the sacrificed animal was much less important than in Roman or Etruscan religion, or Near Eastern religions, but was practiced, especially of the liver, and as part of the cult of Apollo. Generally, the Greeks put more faith in observing the behaviour of birds.[12] For a smaller and simpler offering, a grain of incense could be thrown on the sacred fire,[13] and outside the cities farmers made simple sacrificial gifts of plant produce as the "first fruits" were harvested.[14] Although the grand form of sacrifice called the hecatomb (meaning 100 bulls) might in practice only involve a dozen or so, at large festivals the number of cattle sacrificed could run into the hundreds, and the numbers feasting on them well into the thousands. The enormous Hellenistic structures of the Altar of Hieron and Pergamon Altar were built for such occasions.

The evidence of the existence of such practices is clear in some ancient Greek literature, especially in Homer's epics. Throughout the poems, the use of the ritual is apparent at banquets where meat is served, in times of danger or before some important endeavor to gain the favor of the gods. For example, in Homer's Odyssey Eumaeus sacrifices a pig with prayer for his unrecognizable master Odysseus. However, in Homer's Iliad, which partly reflects very early Greek civilization, not every banquet of the princes begins with a sacrifice.[15]

These sacrificial practices, described in these pre-Homeric eras, share commonalities to the 8th century forms of sacrificial rituals. Furthermore, throughout the poem, special banquets are held whenever gods indicated their presence by some sign or success in war. Before setting out for Troy, this type of animal sacrifice is offered. Odysseus offers Zeus a sacrificial ram in vain. The occasions of sacrifice in Homer's epic poems may shed some light onto the view of the gods as members of society, rather than as external entities, indicating social ties. Sacrificial rituals played a major role in forming the relationship between humans and the divine.[16]

It has been suggested that the Chthonic deities, distinguished from Olympic deities by typically being offered the holocaust mode of sacrifice, where the offering is wholly burnt, may be remnants of the native Pre-Hellenic religion and that many of the Olympian deities may come from the Proto-Greeks who overran the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula in the late third millennium BC.[17]

In the Hellenistic period after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC, several new philosophical movements began to question the ethics of animal sacrifice.[18]

Scythians

According to the unique account by the Greek author Herodotus (c 484–c 425 BC), the Scythians sacrificed various kinds of livestock, though the most prestigious offering was considered to be the horse. The pig, on the other hand, was never offered in sacrifice, and apparently the Scythians were loath to keep swine within their lands.[19] Herodotus describes the Scythian manner of sacrifice as follows:

The victim stands with its fore-feet tied, and the sacrificing priest stands behind the victim, and by pulling the end of the cord he throws the beast down; and as the victim falls, he calls upon the god to whom he is sacrificing, and then at once throws a noose round its neck, and putting a small stick into it he turns it round and so strangles the animal, without either lighting a fire or making any first offering from the victim or pouring any libation over it: and when he has strangled it and flayed off the skin, he proceeds to boil it. [...] Then when the flesh is boiled, the sacrificer takes a first offering of the flesh and of the vital organs and casts it in front of him.[20]

Herodotus goes on to describe the human sacrifice of prisoners, conducted in a different manner.

Ancient Rome

The most potent offering in Ancient Roman religion was animal sacrifice, typically of domesticated animals such as cattle, sheep and pigs. Each was the best specimen of its kind, cleansed, clad in sacrificial regalia and garlanded; the horns of oxen might be gilded. Sacrifice sought the harmonisation of the earthly and divine, so the victim must seem willing to offer its own life on behalf of the community; it must remain calm and be quickly and cleanly dispatched.[21]

Sacrifice to deities of the heavens (di superi, "gods above") was performed in daylight, and under the public gaze. Deities of the upper heavens required white, infertile victims of their own sex: Juno a white heifer (possibly a white cow); Jupiter a white, castrated ox (bos mas) for the annual oath-taking by the consuls. Di superi with strong connections to the earth, such as Mars, Janus, Neptune and various genii – including the Emperor's – were offered fertile victims. After the sacrifice, a banquet was held; in state cults, the images of honoured deities took pride of place on banqueting couches and by means of the sacrificial fire consumed their proper portion (exta, the innards). Rome's officials and priests reclined in order of precedence alongside and ate the meat; lesser citizens may have had to provide their own.[22]

Chthonic gods such as Dis pater, the di inferi ("gods below"), and the collective shades of the departed (di Manes) were given dark, fertile victims in nighttime rituals. Animal sacrifice usually took the form of a holocaust or burnt offering, and there was no shared banquet, as "the living cannot share a meal with the dead".[23] Ceres and other underworld goddesses of fruitfulness were sometimes offered pregnant female animals; Tellus was given a pregnant cow at the Fordicidia festival. Color had a general symbolic value for sacrifices. Demigods and heroes, who belonged to the heavens and the underworld, were sometimes given black-and-white victims. Robigo (or Robigus) was given red dogs and libations of red wine at the Robigalia for the protection of crops from blight and red mildew.[22]

A sacrifice might be made in thanksgiving or as an expiation of a sacrilege or potential sacrilege (piaculum);[24] a piaculum might also be offered as a sort of advance payment; the Arval Brethren, for instance, offered a piaculum before entering their sacred grove with an iron implement, which was forbidden, as well as after.[25] The pig was a common victim for a piaculum.[26]

The same divine agencies who caused disease or harm also had the power to avert it, and so might be placated in advance. Divine consideration might be sought to avoid the inconvenient delays of a journey, or encounters with banditry, piracy and shipwreck, with due gratitude to be rendered on safe arrival or return. In times of great crisis, the Senate could decree collective public rites, in which Rome's citizens, including women and children, moved in procession from one temple to the next, supplicating the gods.[27]

Extraordinary circumstances called for extraordinary sacrifice: in one of the many crises of the Second Punic War, Jupiter Capitolinus was promised every animal born that spring (see ver sacrum), to be rendered after five more years of protection from Hannibal and his allies.[28] The "contract" with Jupiter is exceptionally detailed. All due care would be taken of the animals. If any died or were stolen before the scheduled sacrifice, they would count as already sacrificed, since they had already been consecrated. Normally, if the gods failed to keep their side of the bargain, the offered sacrifice would be withheld. In the imperial period, sacrifice was withheld following Trajan's death because the gods had not kept the Emperor safe for the stipulated period.[29] In Pompeii, the Genius of the living emperor was offered a bull: presumably a standard practise in Imperial cult, though minor offerings (incense and wine) were also made.[30]

The exta were the entrails of a sacrificed animal, comprising in Cicero's enumeration the gall bladder (fel), liver (iecur), heart (cor), and lungs (pulmones).[31] The exta were exposed for litatio (divine approval) as part of Roman liturgy, but were "read" in the context of the disciplina Etrusca. As a product of Roman sacrifice, the exta and blood are reserved for the gods, while the meat (viscera) is shared among human beings in a communal meal. The exta of bovine victims were usually stewed in a pot (olla or aula), while those of sheep or pigs were grilled on skewers. When the deity's portion was cooked, it was sprinkled with mola salsa (ritually prepared salted flour) and wine, then placed in the fire on the altar for the offering; the technical verb for this action was porricere.[32]

Iron Age Europe

Too little is known about either Celtic paganism or the earlier Germanic equivalent to be confident about their practices, other than the claims of Roman sources that human sacrifice was included - they do not bother to report on the less sensational sacrifice of animals. In the rather later Norse paganism, the blót sacrifice and feast is better recorded. Like the Greeks, the Norse seem to have eaten most of the sacrifice; human prisoners were also sometimes sacrificed.

Abrahamic traditions

Judaism

In Judaism, the qorban is any of a variety of sacrificial offerings described and commanded in the Torah. The most common usages are animal sacrifice (zevah זֶבַח), zevah shelamim (the peace offering) and olah (the "holocaust" or burnt offering). A qorban was an animal sacrifice, such as a bull, sheep, goat, or a dove that underwent shechita (Jewish ritual slaughter). Sacrifices could also consist grain, meal, wine, or incense.[33][34]

The Hebrew Bible says that Yahweh commanded the Israelites to offer offerings and sacrifices on various altars. The sacrifices were only to be offered by the hands of the Kohanim. Before building the Temple in Jerusalem, when the Israelites were in the desert, sacrifices were offered only in the Tabernacle. After building Solomon's Temple, sacrifices were allowed only there. After the Temple was destroyed, sacrifices was resumed when the Second Temple was built until it was also destroyed in 70 CE. After the destruction of the Second Temple sacrifices were prohibited because there was no longer a Temple, the only place allowed by halakha for sacrifices. Offering of sacrifices was briefly reinstated during the Jewish–Roman wars of the second century CE and was continued in certain communities thereafter.[35][33][36]

The Samaritans,[37] a group historically related to the Jews, practice animal sacrifice in accordance with the Law of Moses.

Christianity

_-_Armenia_2009.JPG.webp)

References to animal sacrifice appear in the New Testament, such as the parents of Jesus sacrificing two doves (Luke 2:24) and the Apostle Paul performing a Nazirite vow even after the death of Christ (Acts 21:23–26).

Christ is referred to by his apostles as "the Lamb of God", the one to whom all sacrifices pointed (Hebrews 10).[38] According to the penal substitution theory of atonement, Christ's crucifixion is comparable to animal sacrifice on a large scale as his death serves as a substitutionary punishment for all of humanity's sins.

Though never a part of the doctrine or theology of any Christian group (and often attracting criticism), some rural Christian communities have continued to sacrifice animals (which are then consumed in a feast) as part of worship, especially at Easter. The animal may be brought into the church before being taken out again and killed. Some villages in Greece sacrifice animals to Orthodox saints in a practice known as kourbania. Sacrifice of a lamb, or less commonly a rooster, is a common practice in Armenian Church,[9] and the Tewahedo Church of Ethiopia and Eritrea. This tradition, called matagh, is believed to stem from pre-Christian pagan rituals. Additionally, some Mayans following a form of Folk Catholicism in Mexico today still sacrifice animals in conjunction with church practices, a ritual practiced in past religions before the arrival of the Spaniards.[39]

Strangite Latter Day Saints

Animal sacrifice was instituted in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite), a minor Latter Day Saint faction founded by James J. Strang in 1844. Strang's Book of the Law of the Lord (1851) deals with the topic of animal sacrifice in chapters 7 and 40.

Given the prohibition on sacrifices for sin contained in III Nephi 9:19-20 (Book of Mormon), Strang did not require sin offerings. Rather, he focused on sacrifice as an element of religious celebrations,[40] especially the commemoration of his own coronation as king over his church, which occurred on July 8, 1850.[41] The head of every house, from the king to his lowest subject, was to offer "a heifer, or a lamb, or a dove. Every man a clean beast, or a clean fowl, according to his household."[42]

While the killing of sacrifices was a prerogative of Strangite priests,[43] female priests were specifically barred from participating in this aspect of the priestly office.[44] "Firstfruits" offerings were also demanded of all Strangite agricultural harvests.[45] Animal sacrifices are no longer practiced by the Strangite organization, though belief in their correctness is still required.

Neither The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints nor the Community of Christ, the two largest Latter Day Saint factions, ever accepted Strang's teachings on this (or any other) subject.

Islam

Muslims engaged in the Hajj (pilgrimage) are obliged to sacrifice a lamb or a goat or join others in sacrificing a cow or a camel during the celebration of the Eid al-Adha,[46][47] an Arabic term that means "Feast of Sacrifice", also known as al-Id al-Kabir (Great Feast), or Qurban Bayrami (Sacrifice Feast) in Turkic influenced cultures, Bakar Id (Goat Feast) in Indian subcontinent and Reraya Qurben in Indonesia.[48] Other Muslims not on the Hajj to Mecca also participate in this sacrifice wherever they are, on the 10th day of the 12th lunar month in the Islamic calendar.[48] It is understood as a symbolic re-enactment of Abraham's sacrifice of a ram in place of his son. Meat from this occasion is divided into three parts, one part is kept by the sacrificing family for food, the other gifted to friends and family, and the third given to the poor Muslims. The sacrificed animal is a sheep, goat, cow or camel. The feast follows a communal prayer at a mosque or open air.[48][49]

The animal sacrifice during the Hajj is a part of nine step pilgrimage ritual. It is, states Campo, preceded by a statement to intention and body purification, inaugural circumambulation of the Kaaba seven times, running between Marwa and Safa hills, encampment at Mina, standing in Arafat, stoning the three Mina satanic pillars with at least forty nine pebbles. Thereafter, animal sacrifice, and this is followed by farewell circumambulation of the Kaaba.[50][51] The Muslims who are not on Hajj also perform a simplified ritual animal sacrifice. According to Campo, the animal sacrifice at the annual Islamic festival has origins in western Arabia in vogue before Islam.[50] The animal sacrifice, states Philip Stewart, is not required by the Quran, but is based on interpretations of other Islamic texts.[52]

The Eid al-Adha is major annual festival of animal sacrifice in Islam. In Indonesia alone, for example, some 800,000 animals were sacrificed in 2014 by its Muslims on the festival, but the number can be a bit lower or higher depending on the economic conditions.[53] According to Lesley Hazleton, in Turkey about 2,500,000 sheep, cows and goats are sacrificed each year to observe the Islamic festival of animal sacrifice, with a part of the sacrificed animal given to the needy who did not sacrifice an animal.[54] According to The Independent, nearly 10,000,000 animals are sacrificed in Pakistan every year on Eid.[55][56] Countries such as Saudi Arabia transport nearly a million animals every year for sacrifice to Mina (near Mecca). The sacrificed animals at Id al-Adha, states Clarke Brooke, include the four species considered lawful for the Hajj sacrifice: sheep, goats, camels and cattle, and additionally, cow-like animals initialing the water buffalo, domesticated banteng and yaks. Many are brought in from north Africa and parts of Asia.[57]

Other occasions when Muslims perform animal sacrifice include the 'aqiqa, when a child is seven days old, is shaved and given a name. It is believed that the animal sacrifice binds the child to Islam and offers protection to the child from evil.[51]

Killing of animals by dhabihah is ritual slaughter rather than sacrifice.

Hinduism

Practices of Hindu animal sacrifice are mostly associated with Shaktism, and in currents of folk Hinduism strongly rooted in local tribal traditions. Animal sacrifices were carried out in ancient times in India. Hindu scriptures, including the Gita, and the Puranas forbid animal sacrifice.[58][59][60][61]

Animal sacrifice is a part of Durga puja celebrations during the Navratri in eastern states of India. The goddess is offered sacrificial animal in this ritual in the belief that it stimulates her violent vengeance against the buffalo demon.[63] According to Christopher Fuller, the animal sacrifice practice is rare among Hindus during Navratri, or at other times, outside the Shaktism tradition found in the eastern Indian states of West Bengal, Odisha[64] and Assam. Further, even in these states, the festival season is one where significant animal sacrifices are observed.[63] In some Shakta Hindu communities, the slaying of buffalo demon and victory of Durga is observed with a symbolic sacrifice instead of animal sacrifice.[65][66][note 1]

The Rajput of Rajasthan worship their weapons and horses on Navratri, and formerly offered a sacrifice of a goat to a goddess revered as Kuldevi – a practice that continues in some places.[69][70] The ritual requires slaying of the animal with a single stroke. In the past this ritual was considered a rite of passage into manhood and readiness as a warrior.[71] The Kuldevi among these Rajput communities is a warrior-pativrata guardian goddess, with local legends tracing reverence for her during Rajput-Muslim wars.[72]

The tradition of animal sacrifice is being substituted with vegetarian offerings to the Goddess in temples and households around Banaras in Northern India.[73]

There are Hindu temples in Assam and West Bengal India and Nepal where goats, chickens and sometimes water buffalos are sacrificed. These sacrifices are performed mainly at temples following the Shakti school of Hinduism where the female nature of Brahman is worshipped in the form of Kali and Durga.

In some sacred groves of India, particularly in Western Maharashtra, animal sacrifice is practiced to pacify female deities that are supposed to rule the Groves.[74]

Animal sacrifice en masse occurs during the three-day-long Gadhimai festival in Nepal. In 2009 it was speculated that more than 250,000 animals were killed[75] while 5 million devotees attended the festival.[76] However, this practise was later banned in 2015.[77][78][79]

In India, ritual of animal sacrifice is practised in many villages before local deities or certain powerful and terrifying forms of the Devi. In this form of worship, animals, usually goats, are decapitated and the blood is offered to deity often by smearing some of it on a post outside the temple.[80] For instance, Kandhen Budhi is the reigning deity of Kantamal in Boudh district of Orissa, India. Every year, animals like goat and fowl are sacrificed before the deity on the occasion of her annual Yatra/Jatra (festival) held in the month of Aswina (September–October). The main attraction of Kandhen Budhi Yatra is Ghusuri Puja. Ghusuri means a child pig, which is sacrificed to the goddess every three years. Kandhen Budhi is also worshipped at Lather village under Mohangiri GP in Kalahandi district of Orissa, India.[81] (Pasayat, 2009:20-24).

The religious belief of Tabuh Rah, a form of animal sacrifice of Balinese Hinduism includes a religious cockfight where a rooster is used in religious custom by allowing him to fight against another rooster in a religious and spiritual cockfight, a spiritual appeasement exercise of Tabuh Rah.[82] The spilling of blood is necessary as purification to appease the evil spirits, and ritual fights follow an ancient and complex ritual as set out in the sacred lontar manuscripts.[83]

East Asian traditions

Buddhism prohibits all forms of killing, rituals, sacrifices and worship and Taoism generally prohibit killing of animals;[84][85][86] some animal offerings, such as fowl, pigs, goats, fish, or other livestock, are accepted in some Taoism sects and beliefs in Chinese folk religion.[87][88][89]

In Kaohsiung, Taiwan, animal sacrifices are banned in Taoist temples.[90]

In Japan, Iomante was a traditional bear sacrifice that was practiced by the Ainu people.[91]

Traditional African and Afro-American religions

Animal sacrifice is regularly practiced in traditional African and Afro-American religions.[92][93]

The landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of the Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah in 1993 upheld the right of Santería adherents to practice ritual animal sacrifice in the United States of America. Likewise in Texas in 2009, legal and religious issues that related to animal sacrifice, animal rights and freedom of religion were taken to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in the case of Jose Merced, President Templo Yoruba Omo Orisha Texas, Inc., v. City of Euless. The court ruling that the Merced case of the freedom of exercise of religion was meritorious and prevailing and that Merced was entitled under the Texas Religious Freedom and Restoration Act (TRFRA) to an injunction preventing the city of Euless, Texas from enforcing its ordinances that burdened his religious practices relating to the use of animals,[94] (see Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 110.005(a)(2)).

See also

Notes

- In these cases, Shaktism devotees consider animal sacrifice distasteful, practice alternate means of expressing devotion while respecting the views of others in their tradition.[67] A statue of asura demon made of flour, or equivalent, is immolated and smeared with vermilion to remember the blood that had necessarily been spilled during the war.[65][66] Other substitutes include a vegetal or sweet dish considered equivalent to the animal.[68]

References

- Homo Necans: The Anthropology of Ancient Greek Sacrificial Ritual and Myth. trans. Peter Bing. Berkeley: University of California. 1983. ISBN 0-520-05875-5.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Flores, Diane Victoria (2003). Funerary Sacrifice of Animals in the Egyptian Predynastic Period (PDF).

- "In Ancient Egypt, Life Wasn't Easy for Elite Pets". National Geographic. 2015.

- Herodotus, Histories 2.38, 2.39,2.40,2.41,2.42

- Archaeological Institute of America (2016). "Ancient Canaanites Imported Animals from Egypt".

- Jones O'Day, Sharyn; Van Neer, Wim; Ervynck, Anton (2004). Behaviour Behind Bones: The Zooarchaeology of Ritual, Religion, Status and Identity. Oxbow Books. pp. 35–41. ISBN 1-84217-113-5.

- C.Michael Hogan, Knossos Fieldnotes, The Modern Antiquarian (2007) Archived April 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- "New funerary and ritual behaviors of the Neolithic Iberian populations discovered". EurekAlert!. 25 September 2020.

- Burkert (1972), pp. 8-9, google books

- Burkert (1985), 2:1:1, 2:1:2. For more exotic local forms of sacrifice, see the Laphria (festival), Xanthika, and Lykaia. The advantageous division of the animal was supposed to go back to Prometheus's trick on Zeus]]

- Burkert (1985): 2:1:1; to some extent different animals were thought appropriate for different deities, from bulls for Zeus and Poseidon to doves for Aphrodite, Burkert (1985): 2:1:4

- Struck, P.T. (2014). "Animals and Divination", In Campbell, G.L. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life, 2014, Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199589425.013.019, online

- Burkert (1985): 2:1:2

- Burkert (1985): 2:1:4

- Sarah Hitch, King of Sacrifice: Ritual and Royal Authority in the Iliad, online at Harvard University's Center for Hellenic Studies

- Meuli, Griechische Opferbräuche, 1946

- Chadwick, John (1976). The Mycenaean World. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-521-29037-1.

- Burkert (1972), 6-7

- Macaulay (1904:315).

- Macaulay (1904:314).

- Halm, in Rüpke (ed), 239.

- Scheid, in Rüpke (ed), 263 - 271.

- Though the household Lares do just that, and at least some Romans understood them to be ancestral spirits. Sacrifices to the spirits of deceased mortals are discussed below in Funerals and the afterlife.

- Jörg Rüpke, Religion of the Romans (Polity Press, 2007, originally published in German 2001), p. 81 online.

- William Warde Fowler, The Religious Experience of the Roman People (London, 1922), p. 191.

- Robert E.A. Palmer, "The Deconstruction of Mommsen on Festus 462/464 L, or the Hazards of Interpretation", in Imperium sine fine: T. Robert S. Broughton and the Roman Republic (Franz Steiner, 1996), p. 99, note 129 online; Roger D. Woodard, Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult (University of Illinois Press, 2006), p. 122 online. The Augustan historian Livy (8.9.1–11) says P. Decius Mus is "like" a piaculum when he makes his vow to sacrifice himself in battle (devotio).

- Hahn, in Rüpke (ed), 238.

- Beard et al., Vol 1, 32-36.

- Gradel, 21: but this need not imply sacrifice as a mutual contract, breached in this instance. Evidently the gods had the greater power and freedom of choice in the matter. See Beard et al., 34: "The gods would accept as sufficient exactly what they were offered - no more, no less." Human error in the previous annual vows and sacrifice remains a possibility.

- Gradel, 78, 93

- Cicero, De divinatione 2.12.29. According to Pliny (Natural History 11.186), before 274 BC the heart was not included among the exta.

- Robert Schilling, "The Roman Religion", in Historia Religionum: Religions of the Past (Brill, 1969), vol. 1, pp. 471–472, and "Roman Sacrifice," Roman and European Mythologies (University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 79; John Scheid, An Introduction to Roman Religion (Indiana University Press, 2003, originally published in French 1998), p. 84.

- Zotti, Ed (ed.). "Why do Jews no longer sacrifice animals?". The Straight Dope.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Rabbi Zalman Kravitz. "Jews For Judaism". Archived from the original on 2016-03-30. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- "Judaism 101: Qorbanot: Sacrifices and Offerings".

- "What is the Tabernacle of Moses?". Archived from the original on 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- Todd Bolen, “The Samaritan Passover” Archived May 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, ”egrc.net”, March 2015

- “Christ’s Sacrifice Once for All” Archived June 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, ”Bible Gateway”, March 2015

- "Maya and Catholic Religious Syncretism at Chamula, Mexico". Vagabondjourney.com. 2011-11-26. Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- Book of the Law, pp. 293-97. See also http://www.strangite.org/Offering.htm%5B%5D.

- Book of the Law, pg. 293.

- Book of the Law, pp. 293-94.

- Book of the Law, pg. 199, note 2.

- Book of the Law, pg. 199. Unlike other Latter Day Saint organizations at this time, Strang permitted women to serve as Priests and Teachers in his priesthood.

- Book of the Law, pp. 295-97.

- Traditional festivals. 2. M - Z. ABC-CLIO. 2005. p. 132. ISBN 9781576070895.

- Bongmba, Elias Kifon. The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to African Religions. Wiley.com. p. 327.

- Juan Campo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. 342. ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8.

- Bowen, John R. (1992). "On scriptural essentialism and ritual variation: Muslim sacrifice in Sumatra and Morocco". American Ethnologist. Wiley-Blackwell. 19 (4): 656–671. doi:10.1525/ae.1992.19.4.02a00020.

- Juan Campo (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8.

- Edward Hulmes (2013). Ian Richard Netton (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islamic Civilization and Religion. Taylor & Francis. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-1-135-17967-0.

- Philip J. Stewart (1979), Islamic law as a factor in grazing management: The Pilgrimage Sacrifice, The Commonwealth Forestry Review, Vol. 58, No. 1 (175) (March 1979), pp. 27-31

- Animal Sacrifice in the World’s Largest Muslim-Majority Nation, The Wall Street Journal (September 23, 2015)

- Lesley Hazleton (2008). Mary. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-59691-799-6.

- Eid al-Adha 2016: When is it and why does it not fall on the same date every year?, Harriet Agerholm, The Independent (6 September 2016)

- Zaidi, Farrah; Chen, Xue-xin (2011). "A preliminary survey of carrion breeding insects associated with the Eid ul Azha festival in remote Pakistan". Forensic Science International. Elsevier BV. 209 (1–3): 186–194. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.01.027. PMID 21330071.

- Brooke, Clarke (1987). "Sacred Slaughter: The Sacrificing of Animals at theHajjandId al-Adha". Journal of Cultural Geography. Taylor & Francis. 7 (2): 67–88. doi:10.1080/08873638709478508., Quote: "Id al-Adha's lawful sacrificial offerings include the four species prescribed for Hajj sacrifice, sheep, goats, camels and cattle, and additionally, cow-like animals initialing the water buffalo, domesticated banteng and yaks. To meet market demands for sacrificial animals, pastoralists in northern Africa and southwestern Asia increased their flocks and overstocked grazing land, consequently accelerating the deterioration of biotic resources."

- Rod Preece (2001). Animals and Nature: Cultural Myths, Cultural Realities. UBC Press. p. 202. ISBN 9780774807241.

- Kemmerer, Lisa; Nocella, Anthony J. (2011). Call to Compassion: Reflections on Animal Advocacy from the World's Religions. Lantern Books. p. 60. ISBN 9781590562819.

- Stephens, Alan Andrew; Walden, Raphael Walden (2006). For the Sake of Humanity. BRILL. p. 69. ISBN 9004141251.

- Smith, David Whitten; Bur, Elizabeth Geraldine (January 2007). Understanding World Religions: A Road Map for Justice and Peace. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 13. ISBN 9780742550551.

- Christopher John Fuller (2004). The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India. Princeton University Press. p. 141. ISBN 0-691-12048-X.

- Christopher John Fuller (2004). The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India. Princeton University Press. pp. 46, 83–85. ISBN 0-691-12048-X.

- Hardenberg, Roland (2000). "Visnu's Sleep, Mahisa's Attack, Durga's Victory: Concepts of Royalty in a Sacrificial Drama" (PDF). Journal of Social Science. 4 (4): 267. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Hillary Rodrigues 2003, pp. 277-278.

- June McDaniel 2004, pp. 204-205.

- Ira Katznelson; Gareth Stedman Jones (2010). Religion and the Political Imagination. Cambridge University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-1-139-49317-8.

- Rachel Fell McDermott (2011). Revelry, Rivalry, and Longing for the Goddesses of Bengal: The Fortunes of Hindu Festivals. Columbia University Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-231-12919-0.

- Harlan, Lindsey (2003). The goddesses' henchmen gender in Indian hero worship. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. pp. 45 with footnote 55, 58–59. ISBN 978-0195154269. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf; Erndl, Kathleen M. (2000). Is the Goddess a Feminist?: the Politics of South Asian Goddesses. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780814736197.

- Harlan, Lindsey (1992). Religion and Rajput Women. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 61, 88. ISBN 0-520-07339-8.

- Harlan, Lindsey (1992). Religion and Rajput Women. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 0-520-07339-8.

- Rodrigues, Hillary (2003). Ritual Worship of the Great Goddess: The Liturgy of the Durga Puja with interpretation. Albany, New York, USA: State University of New York Press. p. 215. ISBN 07914-5399-5. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- Gadgil, M; VD Vartak (1975). "Sacred Groves of India" (PDF). Journal of the Bombay Natural History. 72 (2): 314.

- Olivia Lang in Bariyapur (2009-11-24). "Hindu sacrifice of 250,000 animals begins". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- "Ritual animal slaughter begins in Nepal". CNN. 2009-11-24. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- Ram Chandra, Shah. "Gadhimai Temple Trust Chairman, Mr Ram Chandra Shah, on the decision to stop holding animal sacrifices during the Gadhimai festival. Later the trust denied the decision, as per trust such decision was obtained forcefully by animal right. Trust said it is not in our hand to stop the sacrifice it is up to people, as trust or priest never ask devotee to offer sacrifice. It is their sole and self decision " (PDF). Humane Society International. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Meredith, Charlotte (29 July 2015). "Thousands of Animals Have Been Saved in Nepal as Mass Slaughter Is Cancelled". Vice News. Vice Media, Inc. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- KUMAR YADAV, PRAVEEN; TRIPATHI, RITESH (29 July 2015). "Gadhimai Trust dismisses reports on animal sacrifice ban". Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 41. ISBN 9780823931798.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2015-02-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bali Today: Love and social life By Jean Couteau, Jean Couteau et al - p.129 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2015-09-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Indonesia Handbook, 3rd, Joshua Eliot, Liz Capaldi, & Jane Bickersteth, (Footprint - Travel Guides) 2001 p.450 Eliot, Joshua; Capaldi, Liz; Bickersteth, Jane (2001). Indonesia. ISBN 1900949512.

- 办丧事或祭祀祖先可以杀生吗 Archived March 31, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- 齋醮略談 Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- 符籙齋醮 Archived April 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "林真-馬年運程, 馬年運氣書,風水、掌相、看相、八字、命理、算命".

- 衣紙2 Archived March 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- 道教拜神用品 Archived July 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "中山大學 West BBS-西子灣站 / 分類佈告 / maev91 / 高雄地名知多少".

- Utagawa, Hiroshi. "The "sending-back" rite in Ainu culture." Japanese Journal of Religious Studies (1992): 255-270.

- Marie-Jose Alcide Saint-Lot (2003). Vodou, a Sacred Theatre: The African Heritage in Haiti. Educa Vision Inc. p. 14. ISBN 9781584321774.

- Insoll, T. Talensi Animal Sacrifice and its Archaeological Implications, p. 231-234

- " Archived October 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Full text of the opinion courtesy of Findlaw.com.

Bibliography

- Hillary Rodrigues (2003). Ritual Worship of the Great Goddess: The Liturgy of the Durga Puja with Interpretations. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-8844-7.

- June McDaniel (2004). Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534713-5.

- Barik, Sarmistha (2009), "Bali Yatra of Sonepur" in Orissa Review, Vol.LXVI, No.2, September, pp. 160–162.

- Burkert, Walter (1972), Homo Necans pp. 6–22

- Burkert, Walter (1985), Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0674362810

- Gihus, Ingvild Saelid. Animals, Gods, and Humans: Changing Ideas to Animals in Greek, Roman, and early Christian Ideas. London; New York: Routeledge, 2006.*Pasayat, C. (2003), Glimpses of Tribal an Folkculture, New Delhi: Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd., pp. 67–84.

- Insoll, T. 2010. Talensi Animal Sacrifice and its Archaeological Implications. World Archaeology 42: 231-244

- Garnsey, Peter. Food and Society in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Pasayat, C. (2009), "Kandhen Budhi" in Orissa Review, Vol.LXVI, No.2, September, pp. 20–24.

- Petropoulou, M.-Z. (2008), Animal Sacrifice in Ancient Greek Religion, Judaism, and Christianity, 100 BC to AD 200, Oxford classical monographs, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-921854-7.

- Rosivach, Vincent J. The System of Public Sacrifice in Fourth-Century Athens. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1994.