Kaaba

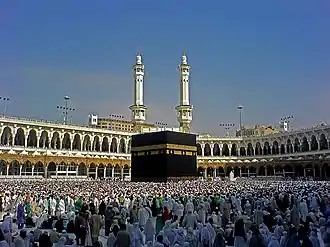

The Kaaba (Arabic: ٱلْكَعْبَة, romanized: al-Kaʿbah, lit. 'The Cube', Arabic pronunciation: [kaʕ.bah]), also spelled Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah (Arabic: ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, romanized: al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah, lit. 'Honored Ka'bah'), is a building at the center of Islam's most important mosque, the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.[1] It is the most sacred site in Islam.[2] It is considered by Muslims to be the Bayt Allah (Arabic: بَيْت ٱللَّٰه, lit. 'House of God') and is the qibla (Arabic: قِبْلَة, direction of prayer) for Muslims around the world when performing salah.

| Kaaba | |

|---|---|

كَعْبَة | |

.jpg.webp) The Kaaba surrounded by pilgrims | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Region | Makkah Province |

| Rite | Tawaf |

| Leadership | President of the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques: Abdul Rahman Al-Sudais |

| Location | |

| Location | Great Mosque of Mecca, Mecca, Hejaz, Saudi Arabia |

Location of the Kaaba in Saudi Arabia  Kaaba (West and Central Asia) | |

| Administration | The Agency of the General Presidency for the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques |

| Geographic coordinates | 21°25′21.0″N 39°49′34.2″E |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 12.86 m (42 ft 2 in) |

| Width | 11.03 m (36 ft 2 in) |

| Height (max) | 13.1 m (43 ft 0 in) |

| Materials | Stone, Marble, Limestone |

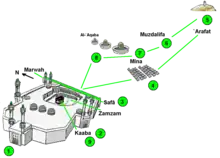

The Kaaba is believed by Muslims to have been rebuilt several times throughout history, most famously by Ibrahim (Abraham) and his son Ismail (Ishmael), when he returned to the valley of Mecca several years after leaving his wife Hajar (Hagar) and Ismail there upon Allah's command. Circling the Kaaba seven times counterclockwise, known as Tawaf (Arabic: طواف, romanized: tawaaf), is an obligatory rite for the completion of the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages.[2] The area around the Kaaba on which pilgrims circumambulate is called the Mataaf.

The Kaaba and the Mataaf are surrounded by pilgrims every day of the Islamic year, except the 9th of Dhu al-Hijjah, known as the Day of Arafah, on which the cloth covering the structure, known as the Kiswah (Arabic: كسوة, romanized: Kiswah, lit. 'Cloth') is changed. However, the most significant increase in their numbers is during Ramadan and the hajj, when millions of pilgrims gather for tawaf.[3][4] According to the Saudi Ministry of Hajj and Umrah, 6,791,100 pilgrims arrived for the Umrah pilgrimage in the Islamic year 1439 AH,[lower-alpha 1] a 3.6% increase from the previous year, with 2,489,406 others arriving for the 1440 AH Hajj.[5]

Lexicology

The literal meaning of the word Ka'bah (Arabic: كعبة) is cube.[6]

In the Qur'an, the Ka'bah is also mentioned by the following names:

- al-Bayt (Arabic: ٱلْبَيْت, lit. 'the house') in 2:125 by Allah.[Quran 2:125]

- Baytī (Arabic: بَيْتِي, lit. 'My House') in 22:26 by Allah.[Quran 22:26]

- Baytik al-Muḥarram (Arabic: بَيْتِكَ ٱلْمُحَرَّم, lit. 'Your Inviolable House') in 14:37 by Ibrahim.[Quran 14:37]

- al-Bayt al-Ḥarām (Arabic: ٱلْبَيْت ٱلْحَرَام, lit. 'The Sacred House') in 5:97 by Allah.[Quran 5:97]

- al-Bayt al-ʿAtīq (Arabic: ٱلْبَيْت ٱلْعَتِيق, lit. 'The Ancient House') in 22:29 by Allah.[Quran 22:29]

The masjid surrounding the Kaaba is called al-Masjid al-Haram ("The Sacred Mosque").

History

Origin

Prior to Islam throughout the Arabian Peninsula, the Kaaba was a holy site for the various Bedouin tribes of the area. Once every lunar year, the Bedouin tribes would make a pilgrimage to Mecca. Setting aside any tribal feuds, they would worship their gods in the Kaaba and trade with each other in the city.[7] Various sculptures and paintings were held inside the Kaaba. A statue of Hubal (the principal idol of Mecca) and statues of other pagan deities are known to have been placed in or around the Kaaba.[8] There were paintings of idols decorating the walls. A picture of 'Isa and his mother Maryam was situated inside the Kaaba and later found by Muhammad after his conquest of Mecca. The iconography portrayed a seated Maryam with her child on her lap.[8] The iconography in the Kaaba also included paintings of other prophets and angels. Undefined decorations, money and a pair of ram's horns were recorded to be inside the Kaaba,.[8] The pair of ram's horns were said to have belonged to the ram sacrificed by Ibrahim in place of his son Ishmael as held by Islamic tradition.[8]

al-Azraqi provides the following narrative on the authority of his grandfather:[8]

I have heard that there was set up in al-Bayt (referring to the Kaaba) a picture (Arabic: تمثال, romanized: Timthal, lit. 'Depiction') of Maryam and 'Isa. ['Ata'] said: "Yes, there was set in it a picture of Maryam adorned (muzawwaqan); in her lap, her son Isa sat adorned."

— al-Azraqi, Akhbar Mecca: History of Mecca[1]

In her book Islam: A Short History, Karen Armstrong asserts that the Kaaba was officially dedicated to Hubal, a Nabatean deity, and contained 360 idols which probably represented the days of the year.[9] However, by the time of Muhammad's era, it seems that the Kaaba was venerated as the shrine of Allah, the High God. Once a year, tribes from all around the Arabian Peninsula, whether Christian or pagan, would converge on Mecca to perform the Hajj pilgrimage, marking the widespread conviction that Allah was the same deity worshipped by monotheists.[9] Alfred Guillaume, in his translation of the Ibn Ishaq's seerah, says that the Kaaba itself might be referred to in the feminine form.[10] Circumambulation was often performed naked by men and almost naked by women.[11] It is disputed whether Allah and Hubal were the same deity or different. Per a hypothesis by Uri Rubin and Christian Robin, Hubal was only venerated by Quraysh and the Kaaba was first dedicated to Allah, a supreme god of individuals belonging to different tribes, while the pantheon of the gods of Quraysh was installed in Kaaba after they conquered Mecca a century before Muhammad's time.[12]

Imoti contends that there were numerous such Kaaba sanctuaries in Arabia at one time, but this was the only one built of stone.[13] The others also allegedly had counterparts of the Black Stone. There was a "Red Stone", in the Kaaba of the South Arabian city of Ghaiman; and the "White Stone" in the Kaaba of al-Abalat (near modern-day Tabala). Grunebaum in Classical Islam points out that the experience of divinity of that period was often associated with the fetishism of stones, mountains, special rock formations, or "trees of strange growth."[14] Armstrong further says that the Kaaba was thought to be at the center of the world, with the Gate of Heaven directly above it. The Kaaba marked the location where the sacred world intersected with the profane; the embedded Black Stone was a further symbol of this as a meteorite that had fallen from the sky and linked heaven and earth.[15]

According to Sarwar, about 400 years before the birth of Muhammad, a man named 'Amr bin Luhayy, who descended from Qahtan and was the king of Hijaz placed an idol of Hubal on the roof of the Kaaba. This idol was one of the chief deities of the ruling Quraysh tribe. The idol was made of red agate and shaped like a human, but with the right hand broken off and replaced with a golden hand. When the idol was moved inside the Kaaba, it had seven arrows in front of it, which were used for divination.[16] To maintain peace among the perpetually warring tribes, Mecca was declared a sanctuary where no violence was allowed within 30 kilometres (20 mi) of the Kaaba. This combat-free zone allowed Mecca to thrive not only as a place of pilgrimage, but also as a trading center.[17]

Many Muslim and academic historians stress the power and importance of the pre-Islamic Mecca. They depict it as a city grown rich on the proceeds of the spice trade. Crone believes that this is an exaggeration and that Mecca may only have been an outpost for trading with nomads for leather, cloth, and camel butter. Crone argues that if Mecca had been a well-known center of trade, it would have been mentioned by later authors such as Procopius, Nonnosus, or the Syrian church chroniclers writing in Syriac. The town is absent, however, from any known geographies or histories written in the three centuries before the rise of Islam.[18] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, "before the rise of Islam, it was revered as a sacred sanctuary and was a site of pilgrimage."[19] According to historian Eduard Glaser, the name "Kaaba" may have been related to the southern Arabian or Ethiopian word "mikrab", signifying a temple.[20] Again, Crone disputes this etymology.

In Samaritan literature, the Samaritan Book of the Secrets of Moses (Asatir) claims that Ishmael and his eldest son Nebaioth built the Kaaba as well as the city of Mecca."[21] The Asatir book was likely compiled in the 10th century CE,[22] though Moses Gaster suggested in 1927 that it was written no later than the second half of the 3rd century BCE.[23]

According to Islamic opinion

The Qur'an contains several verses regarding the origin of the Kaaba. It states that the Kaaba was the first House of Worship for mankind, and that it was built by Ibrahim and Ismail on Allah's instructions.[24][25][26]

Verily, the first House (of worship) appointed for mankind was that at Bakkah (Makkah), full of blessing, and a guidance for mankind.

Behold! We gave the site, to Ibrahim, of the (Sacred) House, (saying): "Associate not anything (in worship) with Me; and sanctify My House for those who compass it round, or stand up, or bow, or prostrate themselves (therein in prayer)."

And remember Ibrahim and Ismail raised the foundations of the House (With this prayer): "Our Lord! Accept (this service) from us: For Thou art the All-Hearing, the All-knowing."

Ibn Kathir, in his famous exegesis (tafsir) of the Quran, mentions two interpretations among the Muslims on the origin of the Kaaba. One is that the shrine was a place of worship for angels (mala'ikah) before the creation of man. Later, a house of worship was built on the location and was lost during the flood in Noah's time and was finally rebuilt by Abraham and Ishmael as mentioned later in the Quran. Ibn Kathir regarded this tradition as weak and preferred instead the narration by Ali ibn Abi Talib that although several other temples might have preceded the Kaaba, it was the first Bayt Allah ("House of God"), dedicated solely to Him, built by His instruction, and sanctified and blessed by Him, as stated in Quran 22:26–29.[36] A hadith in Sahih al-Bukhari states that the Kaaba was the first masjid on Earth, and the second was the Temple in Jerusalem.[37]

While Abraham was building the Kaaba, an angel brought to him the Black Stone which he placed in the eastern corner of the structure. Another stone was the Maqam Ibrahim, the Station of Abraham, where Abraham stood for elevation while building the structure. The Black Stone and the Maqam Ibrahim are believed by Muslims to be the only remnant of the original structure made by Abraham as the remaining structure had to be demolished and rebuilt several times over history for its maintenance. After the construction was complete, God enjoined the descendants of Ishmael to perform an annual pilgrimage: the Hajj and the Korban, sacrifice of cattle. The vicinity of the shrine was also made a sanctuary where bloodshed and war were forbidden.[Quran 22:26–33]

According to Islamic tradition, over the millennia after Ishmael's death, his progeny and the local tribes who settled around the Zamzam well gradually turned to polytheism and idolatry. Several idols were placed within the Kaaba representing deities of different aspects of nature and different tribes. Several rituals were adopted in the pilgrimage including doing naked circumambulation.[11] A king named Tubba' is considered the first one to have a door be built for the Kaaba according to sayings recorded in Al-Azraqi's Akhbar Makka.[38]

Ptolemy and Diodorus Siculus

Writing in the Encyclopedia of Islam, Wensinck identifies Mecca with a place called Macoraba mentioned by Ptolemy.[39][20] G. E. von Grunebaum states: "Mecca is mentioned by Ptolemy. The name he gives it allows us to identify it as a South Arabian foundation created around a sanctuary."[40] In Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam, Patricia Crone argues that the identification of Macoraba with Mecca is false and that Macoraba was a town in southern Arabia in what was then known as Arabia Felix.[41] A recent study has revisited the arguments for Macoraba and found them unsatisfactory.[42]

Based on an earlier report by Agatharchides of Cnidus, Diodorus Siculus mentions a temple along the Red Sea coast, "which is very holy and exceedingly revered by all Arabians".[43] Edward Gibbon believed that this was the Kaaba.[44] However, Ian D. Morris argues that Gibbon had misread the source: Diodorus puts the temple too far north for it to have been Mecca.[45]

Khuzistan Chronicle

This short Nestorian (Christian origin) chronicle written no later than the 660s CE covers the history up to the Arab conquest and also gives an interesting note on Arabian geography. The section covering the geography starts with a speculation about the origin of the Muslim sanctuary in Arabia:

"Regarding the K'bta (Kaaba) of Abraham, we have been unable to discover what it is except that, because the blessed Abraham grew rich in property and wanted to get away from the envy of the Canaanites, he chose to live in the distant and spacious parts of the desert. Since he lived in tents, he built that place for the worship of God and for the offering of sacrifices. It took its present name from what it had been, since the memory of the place was preserved with the generations of their race. Indeed, it was no new thing for the Arabs to worship there, but goes back to antiquity, to their early days, in that they show honor to the father of the head of their people."[46]

This is an early record from the Rashidun caliphate, of a Christian origin that explicitly mentions the Kaaba, and confirms the idea that not just the Arabs but certain Christians as well, associated the site with Abraham in the seventh century. This is the second dateable text mentioning the Kaaba, first being some verses from the Quran.

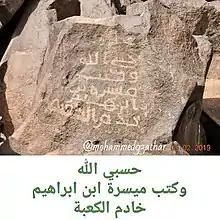

Rock inscriptions from early Islam: Documentary evidence for the Kaaba.

Saudi archeologist Mohammed Almaghthawi discovered some rock inscriptions mentioning the Masjid Al Haram and the Kaaba, dating back to the first and second centuries of Islam. One of them reads as follows:

"God suffices and wrote Maysara bin Ibrahim Servant of the Kaaba (Khadim al-Kaaba)."[47]

Professor Juan Cole is of the opinion that the inscription is likely from the second century A.H. (c. 718 – 815 AD).

Muhammad's era

During Muhammad's lifetime (570–632 CE), the Kaaba was considered a holy site by the local Arabs. Muhammad took part in the reconstruction of the Kaaba after its structure was damaged due to floods around 600 CE. Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasūl Allāh, one of the biographies of Muhammad (as reconstructed and translated by Guillaume), describes Muhammad settling a quarrel between the Meccan clans as to which clan should set the Black Stone in its place. According to Ishaq's biography, Muhammad's solution was to have all the clan elders raise the cornerstone on a cloak, after which Muhammad set the stone into its final place with his own hands.[49][50] Ibn Ishaq says that the timber for the reconstruction of the Kaaba came from a Greek ship that had been wrecked on the Red Sea coast at Shu'aybah and that the work was undertaken by a Coptic carpenter called Baqum.[51] Muhammad's Isra' is said to have taken him from the Kaaba to the Masjid al-Aqsa and heavenwards from there.

Muslims initially considered Jerusalem as their qibla, or prayer direction, and faced toward it while offering prayers; however, pilgrimage to the Kaaba was considered a religious duty though its rites were not yet finalized. During the first half of Muhammad's time as a prophet while he was at Mecca, he and his followers were severely persecuted which eventually led to their migration to Medina in 622 CE. In 624 CE, Muslims believe the direction of the qibla was changed from the Masjid al-Aqsa to the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, with the revelation of Surah 2, verse 144.[Quran 2:144][52] In 628 CE, Muhammad led a group of Muslims towards Mecca with the intention of performing the Umrah, but was prevented from doing so by the Quraysh. He secured a peace treaty with them, the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, which allowed the Muslims to freely perform pilgrimage at the Kaaba from the following year.[53]

At the culmination of his mission,[54] in 630 CE, after the allies of the Quraysh, the Banu Bakr, violated the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, Muhammad conquered Mecca. His first action was to remove statues and images from the Kaaba.[55] According to reports collected by Ibn Ishaq and al-Azraqi, Muhammad spared a painting of Mary and Jesus, and a fresco of Abraham.[56][55][57]

Narrated Abdullah: When the Prophet entered Mecca on the day of the conquest, there were 360 idols around the Kaaba. The Prophet started striking them with a stick he had in his hand and was saying, "Truth has come and Falsehood has vanished..." (Qur'an 17:81)"

Al-Azraqi further conveys how Muhammad, after he entered the Kaaba on the day on the conquest, ordered all the pictures erased except that of Maryam

Shihab (said) that the Prophet (peace be upon him) entered the Kaaba on the day of the conquest, and in it was a picture of the angels (mala'ika), among others, and he saw a picture of Ibrahim and he said: "May Allah kill those representing him as a venerable old man casting arrows in divination (shaykhan yastaqsim bil-azlam)." Then he saw the picture of Maryam, so he put his hands on it and he said: "Erase what is in it [the Kaaba] in the way of pictures except the picture of Maryam."

— al-Azraqi, Akhbar Mecca: History of Mecca

After the conquest, Muhammad restated the sanctity and holiness of Mecca, including its Masjid al-Haram, in Islam.[58] He performed the Hajj in 632 CE called the Hujjat ul-Wada' ("Farewell Pilgrimage") since Muhammad prophesied his impending death on this event.[59]

After Muhammad

-2.jpg.webp)

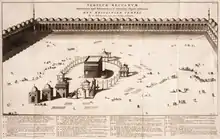

The Kaaba has been repaired and reconstructed many times. The structure was severely damaged by a fire on 3 Rabi' I 64 AH or Sunday, 31 October 683 CE, during the first siege of Mecca in the war between the Umayyads and 'Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr,[60] an early Muslim who ruled Mecca for many years between the death of ʿAli and the consolidation of power by the Umayyads. 'Abdullah rebuilt it to include the hatīm. He did so on the basis of a tradition (found in several hadith collections) that the hatīm was a remnant of the foundations of the Abrahamic Kaaba, and that Muhammad himself had wished to rebuild it so as to include it.

The Kaaba was bombarded with stones in the second siege of Mecca in 692, in which the Umayyad army was led by al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf. The fall of the city and the death of 'Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr allowed the Umayyads under 'Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan to finally reunite all the Islamic possessions and end the long civil war. In 693 CE, 'Abd al-Malik had the remnants of al-Zubayr's Kaaba razed, and rebuilt it on the foundations set by the Quraysh. The Kaaba returned to the cube shape it had taken during Muhammad's time.

During the Hajj of 930 CE, the Shi'ite Qarmatians attacked Mecca under Abu Tahir al-Jannabi, defiled the Zamzam Well with the bodies of pilgrims and stole the Black Stone, taking it to the oasis in Eastern Arabia known as al-Aḥsāʾ, where it remained until the Abbasids ransomed it in 952 CE. The basic shape and structure of the Kaaba have not changed since then.[61]

After heavy rains and flooding in 1626, the walls of the Kaaba collapsed and the Mosque was damaged. The same year, during the reign of Ottoman Emperor Murad IV, the Kaaba was rebuilt with granite stones from Mecca, and the Mosque was renovated.[62] The Kaaba's appearance has not changed since then.

The Kaaba is depicted on the reverse of 500 Saudi riyal, and the 2000 Iranian rial banknotes.[63]

Architecture and interior

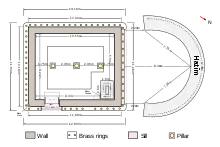

The Kaaba is a cuboid-shaped structure made of stones. It is approximately 13.1 m (43 ft 0 in) tall (some claim 12.03 m or 39 ft 5 1⁄2 in), with sides measuring 11.03 m × 12.86 m (36 ft 2 1⁄2 in × 42 ft 2 1⁄2 in).[64][65] Inside the Kaaba, the floor is made of marble and limestone. The interior walls, measuring 13 m × 9 m (43 ft × 30 ft), are clad with tiled, white marble halfway to the roof, with darker trimmings along the floor. The floor of the interior stands about 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) above the ground area where tawaf is performed.

The wall directly adjacent to the entrance of the Kaaba has six tablets inlaid with inscriptions, and there are several more tablets along the other walls. Along the top corners of the walls runs a Black cloth embroidered with gold Qur'anic verses. Caretakers anoint the marble cladding with the same scented oil used to anoint the Black Stone outside. Three pillars (some erroneously report two) stand inside the Kaaba, with a small altar or table set between one and the other two. Lamp-like objects (possible lanterns or crucible censers) hang from the ceiling. The ceiling itself is of a darker colour, similar in hue to the lower trimming. The Bāb ut-Tawbah—on the right wall (right of the entrance) opens to an enclosed staircase that leads to a hatch, which itself opens to the roof. Both the roof and ceiling (collectively dual-layered) are made of stainless steel-capped teak wood.

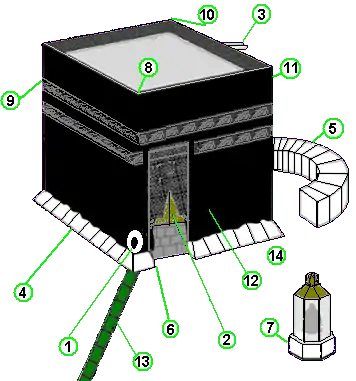

Each numbered item in the following list corresponds to features noted in the diagram image.

- The Ḥajar al-Aswad (Arabic: الحجر الأسود, romanized: al-Hajar al-Aswad, lit. 'The Black Stone'), is located on the Kaaba's eastern corner. It is the location where Muslims start their circumambulation of the Kaaba, known as the tawaf.

- The entrance is a door set 2.13 m (7 ft 0 in) above the ground on the north-eastern wall of the Kaaba, called the Bab ar-Rahmah (Arabic: باب الرحمة, romanized: Bab ar-Rahmah, lit. 'Door of Mercy'), that also acts as the façade.[2] In 1979, the 300 kg (660 lb) gold doors made by artist Ahmad bin Ibrahim Badr, replaced the old silver doors made by his father, Ibrahim Badr, in 1942.[66] There is a wooden staircase on wheels, usually stored in the mosque between the arch-shaped gate of Banū Shaybah and the Zamzam Well. The oldest surviving door dates back to 1045 CE.[38]

- The Mīzāb al-Raḥmah, commonly shortened to Mīzāb or Meezab is a rain spout made of gold. Added when the Kaaba was rebuilt in 1627, after a flood in 1626 caused three of the four walls to collapse.

- This slant structure, covering three sides of the Kaaba, is known as the Shadherwaan (Arabic: شاذروان) and was added in 1627 along with the Mīzāb al-Raḥmah to protect the foundation from rainwater.

- The Hatīm (also romanized as hateem) and also known as the Hijr Ismail, is a low wall that was part of the original Kaaba. It is a semi-circular wall opposite, but not connected to, the north-west wall of the Kaaba. It is 1.31 m (4 ft 3 1⁄2 in) in height and 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) in width, and is composed of white marble. The space between the hatīm and the Kaaba was originally part of the Kaaba, and is thus not entered during the tawaf.

- al-Multazam, the roughly 2 m (6 1⁄2 ft) space along the wall between the Black Stone and the entry door. It is sometimes considered pious or desirable for a pilgrim to touch this area of the Kaaba, or perform dua here.

- The Station of Ibrahim (Maqam Ibrahim) is a glass and metal enclosure with what is said to be an imprint of Abraham's feet. Ibrahim is said to have stood on this stone during the construction of the upper parts of the Kaaba, raising Ismail on his shoulders for the uppermost parts.[67]

- The corner of the Black Stone. It faces very slightly southeast from the center of the Kaaba. The four corners of the Kaaba roughly point toward the four cardinal directions of the compass.[2]

- The Rukn al-Yamani (Arabic: الركن اليمني, romanized: ar-Rukn al-Yamani, lit. 'The Yemeni Corner'), also known as Rukn-e-Yamani or Rukn-e-Yemeni, is the corner of the Kaaba facing slightly southwest from the center of the Kaaba.[2][65]

- The Rukn ush-Shami (Arabic: الركن الشامي, romanized: ar-Rukn ash-Shami, lit. 'The Levantine Corner'), also known as Rukn-e-Shami, is the corner of the Kaaba facing very slightly northwest from the center of the Kaaba.[2][65]

- The Rukn al-'Iraqi (Arabic: الركن العراقي, romanized: ar-Rukn al-'Iraqi, lit. 'The Iraqi Corner'), is the corner that faces slightly northeast from the center of the Kaaba.

- Kiswah, the embroidered covering. Kiswa is a black silk and gold curtain which is replaced annually during the Hajj pilgrimage.[68][69] Two-thirds of the way up is the hizam, a band of gold-embroidered Quranic text, including the Shahada, the Islamic declaration of faith. The curtain over the door of the Kaaba is especially ornate and is known as the sitara or burqu'.[70] The hizam and sitara have inscriptions embroidered in gold and silver wire,[71] including verses from the Quran and supplications to Allah.[72][73]

- Marble stripe marking the beginning and end of each circumambulation.[74]

Note: The major (long) axis of the Kaaba has been observed to align with the rising of the star Canopus toward which its southern wall is directed, while its minor axis (its east–west facades) roughly align with the sunrise of summer solstice and the sunset of winter solstice.[75][76]

Significance in Islam

The Kaaba is the holiest site in Islam,[77] and is often called by names such as the Bayt Allah (Arabic: بيت الله, romanized: Bayt Allah, lit. 'House of Allah').[78][79] and Bayt Allah al-Haram (Arabic: بيت الله الحرام, romanized: Bayt Allah il-Haram, lit. 'The Sacred House of Allah').

Tawaf

Tawaf (Arabic: طَوَاف, lit. 'going about') is one of the Islamic rituals of pilgrimage and is compulsory during both the Hajj and Umrah. Pilgrims go around the Kaaba (the most sacred site in Islam) seven times in a counterclockwise direction; the first three at a hurried pace on the outer part of the Mataaf and the latter four times closer to the Kaaba at a leisurely pace.[80] The circling is believed to demonstrate the unity of the believers in the worship of the One God, as they move in harmony together around the Kaaba, while supplicating to God.[81][82] To be in a state of Wudu (ablution) is mandatory while performing tawaf as it is considered to be a form of worship ('ibadah).

Tawaf begins from the corner of the Kaaba with the Black Stone. If possible, Muslims are to kiss or touch it, but this is often not possible because of the large crowds. They are also to chant the Basmala and Takbir each time they complete one revolution. Hajj pilgrims are generally advised to "make ṭawāf" at least twice – once as part of the Hajj, and again before leaving Mecca.[83]

The five types of ṭawāf are:

- Ṭawāf al-Qudūm (arrival ṭawāf) is performed by those not residing in Mecca once reaching the Holy City.

- Ṭawāf aṭ-Ṭaḥīyah (greeting ṭawāf) is performed after entering Al-Masjid al-Haram at any other times and is mustahab.

- Ṭawāf al-'Umrah (Umrah ṭawāf) refers to the ṭawāf performed specifically for Umrah.

- Ṭawāf al-Wadā' ("farewell ṭawāf") is performed before leaving Mecca.

- Ṭawāf az-Zīyārah (ṭawāf of visiting), Ṭawāf al-'Ifāḍah (ṭawāf of compensation) or Ṭawāf al-Ḥajj (Hajj ṭawāf) is performed after completing the Hajj.

As the Qibla

The Qibla is the direction faced during prayer.[Quran 2:143–144] The direction faced during prayer is the direction of where the Kaaba is, relative to the person praying. Apart from praying, Muslims generally consider facing the Qibla while reciting the Quran to be a part of good etiquette.

Cleaning

The building is opened biannually for the ceremony of "The Cleaning of the Sacred Kaaba" (Arabic: تنظيف الكعبة المشرفة, romanized: Tanzif al-Ka'bat al-Musharrafah, lit. 'Cleaning of the Sacred Cube'). The ceremony takes place on the 1st of Sha'baan, the eighth month of the Islamic calendar, approximately thirty days before the start of the month of Ramadan and on the 15th of Muharram, the first month. The keys to the Kaaba are held by the Banī Shaybah (Arabic: بني شيبة) tribe, an honor bestowed upon them by Muhammad.[84] Members of the tribe greet visitors to the inside of the Kaaba on the occasion of the cleaning ceremony.[85]

The Governor of the Makkah Province and accompanying dignitaries clean the interior of the Kaaba using cloths dipped in Zamzam water scented with Oud perfume. Preparations for the washing start a day before the agreed date, with the mixing of Zamzam water with several luxurious perfumes including Tayef rose, 'oud and musk. Zamzam water mixed with rose perfume is splashed on the floor and is wiped with palm leaves. Usually, the entire process is completed in two hours.[86]

Notes

- 22 September 2017 – 10 September 2018 CE, using tabular calculations rather than the direct lunar observation method. See Islamic New Year#Gregorian correspondence.

References

- Al-Azraqi (2003). Akhbar Mecca: History of Mecca. p. 262. ISBN 9773411273.

- Wensinck, A. J; Kaʿba. Encyclopaedia of Islam IV p. 317

- "In pictures: Hajj pilgrimage". BBC News. 7 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- "As Hajj begins, more changes and challenges in store".

- "Limited to Actual Haj". General Authority for Statistics. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Hans Wehr, Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, 1994.

- Timur Kuran, “Commercial Life under Islamic Rule,” in The Long Divergence : How Islamic Law Held Back the Middle East. (Princeton University Press, 2011), 45–62.

- King, G. R. D. (2004). "The Paintings of the Pre-Islamic Kaʿba". Muqarnas. 21: 219–229. JSTOR 1523357.

- Karen Armstrong (2002). Islam: A Short History. pp. 11. ISBN 0-8129-6618-X.

- Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad (1955). Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah – The Life of Muhammad Translated by A. Guillaume. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 85 footnote 2. ISBN 9780196360331.

The text reads 'O God, do not be afraid', the second footnote reads 'The feminine form indicates the Ka'ba itself is addressed'

- Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad (1955). Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah – The Life of Muhammad Translated by A. Guillaume. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 88–9. ISBN 9780196360331.

- Christian Julien Robin (2012). Arabia and Ethiopia. In The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press USA. pp. 304–305. ISBN 9780195336931.

- Imoti, Eiichi. "The Ka'ba-i Zardušt", Orient, XV (1979), The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan, pp. 65–69.

- Grunebaum, Classical Islam, p. 24

- Armstrong, Jerusalem, p. 221

- Francis E. Peters, Muhammad and the origins of Islam, SUNY Press, 1994, p. 109.

- Armstrong, Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths, pp. 221–22

- Crone, Patricia (2004). Makkan Trade and the Rise of Islam. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias. p. 137

- Britannica 2002 Deluxe Edition CD-ROM, "Ka'bah".

- Wensinck, A. J; Kaʿba. Encyclopaedia of Islam IV p. 318 (1927, 1978)

- Gaster, Moses (1927). The Asatir: the Samaritan book of Moses. London: The Royal Asiatic Society. pp. 262, 71.

Ishmaelites built Mecca (Baka, Bakh)

- Crown, Alan David (2001). Samaritan Scribes and Manuscripts. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. p. 27.

- M. Gaster, The Asatir: The Samaritan Book of the "Secrets of Moses", London (1927), p. 160

- Michigan Consortium for Medieval and Early Modern Studies (1986). Goss, V. P.; Bornstein, C. V. (eds.). The Meeting of Two Worlds: Cultural Exchange Between East and West During the Period of the Crusades. 21. Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University. p. 208. ISBN 0918720583.

- Mustafa Abu Sway. "The Holy Land, Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Qur'an, Sunnah and other Islamic Literary Source" (PDF). Central Conference of American Rabbis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2011.

- Dyrness, W. A. (29 May 2013). Senses of Devotion: Interfaith Aesthetics in Buddhist and Muslim Communities. 7. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 25. ISBN 978-1620321362.

- Quran 3:96 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- An alternative version is in Pickthall, Muhammad M. (ed.). "The Quran". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

Lo! the first Sanctuary appointed for mankind was that at Becca, a blessed place, a guidance to the peoples;

- Another version is in Shakir, M. H. (ed.). "The Quran". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

Most surely the first house appointed for men is the one at Bekka, blessed and a guidance for the nations.

- Quran 22:26 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- Another version is in Pickthall, Muhammad M. (ed.). "The Quran". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

And (remember) when We prepared for Abraham the place of the (holy) House, saying: Ascribe thou no thing as partner unto Me, and purify My House for those who make the round (thereof) and those who stand and those who bow and make prostration.

- Another version is in Shakir, M. H. (ed.). "The Quran". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

And when We assigned to Ibrahim the place of the House, saying: Do not associate with Me aught, and purify My House for those who make the circuit and stand to pray and bow and prostrate themselves.

- Quran 2:127 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- Another version is in Pickthall, Muhammad M. (ed.). "The Quran". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

And when Abraham and Ishmael were raising the foundations of the House, (Abraham prayed): Our Lord! Accept from us (this duty). Lo! Thou, only Thou, art the Hearer, the Knower.

- Another version is in Shakir, M. H. (ed.). "The Quran". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

And when Ibrahim and Ismail raised the foundations of the House: Our Lord! accept from us; surely Thou art the Hearing, the Knowing:

- Tafsir Ibn Kathir on 3:96.

- Sahih Bukhari. Book 55, Hadith 585.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "IN PICTURES: Six doors of Ka'aba over 5,000 years". Al Arabiya. 26 December 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Neuwirth, Angelika; Nicolai Sinai, Michael (2010). The Qur'an in context historical and literary investigations into the Qur'anic milieu (PDF). Leiden: Brill. pp. 63, 123, 83, 295. ISBN 9789047430322. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2015.

- G. E. Von Grunebaum. Classical Islam: A History 600–1258, p. 19

- Crone, Patricia (2004). Makkan Trade and the Rise of Islam. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias. pp. 134–137

- Morris, Ian D. (2018). "Mecca and Macoraba" (PDF). Al-ʿUṣūr Al-Wusṭā. 26: 1–60. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Siculus, Diodorus. Bibliotheca Historica. Book 3 Chapter 44.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Gibbon, Edward (1862). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Book 5 pp. 223–224.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Morris, Ian D. (2018). "Mecca and Macoraba" (PDF). Al-ʿUṣūr Al-Wusṭā. 26: 1–60, pp. 42–43, n. 200. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Robert G., Hoyland (1997). Seeing Islam as others saw it. THE DARWIN PRESS. p. 187.

- Juan, Cole (2020). "Hijazi Rock Inscriptions, Love of the Prophet, and Very Early Islam: Essays from Informed Comment". Hijazi Rock Inscriptions, Love of the Prophet, and Very Early Islam: Essays from Informed Comment.

- University of Southern California. "The Prophet of Islam – His Biography". Archived from the original on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2006.

- Guillaume, A. (1955). The Life of Muhammad. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 84–87

- Saifur Rahman al-Mubarakpuri, translated by Issam Diab (1979). "Muhammad's Birth and Forty Years prior to Prophethood". Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum (The Sealed Nectar): Memoirs of the Noble Prophet. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- Cyril Glasse, New Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 245. Rowman Altamira, 2001. ISBN 0-7591-0190-6

- Saifur Rahman. The Sealed Nectar. pp. 130.

- Saifur Rahman. The Sealed Nectar. pp. 213.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (13 October 2014). A history of Islamic societies. ISBN 9780521514309. OCLC 853114008.

- Ellenbogen, Josh; Tugendhaft, Aaron (18 July 2011). Idol Anxiety. Stanford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780804781817.

When Muhammad ordered his men to cleanse the Kaaba of the statues and pictures displayed there, he spared the paintings of the Virgin and Child and of Abraham.

- Guillaume, Alfred (1955). The Life of Muhammad. A translation of Ishaq's "Sirat Rasul Allah". Oxford University Press. p. 552. ISBN 978-0196360331. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

Quraysh had put pictures in the Ka'ba including two of Jesus son of Mary and Mary (on both of whom be peace!). ... The apostle ordered that the pictures should be erased except those of Jesus and Mary.

- Rogerson, Barnaby (2003). The Prophet Muhammad: A Biography. Paulist Press. p. 190. ISBN 9781587680298.

Muhammad raised his hand to protect an icon of the Virgin and Child and a painting of Abraham, but otherwise his companions cleared the interior of its clutter of votive treasures, cult implements, statuettes and hanging charms.

- W. M. Flinders Petrie; Hans F. Helmolt; Stanley Lane-Poole; Robert Nisbet Bain; Hugo Winckler; Archibald H. Sayce; Alfred Russel Wallace; William Lee-Warner; Holland Thompson; W. Stewart Wallace (1915). The Book of History: A History of All Nations From the Earliest Times to the Present. The Grolier Society.

- Saifur Rahman. The Sealed Nectar. p. 298.

- "On this day in 683 AD: The Kaaba, the holiest site in Islam, is burned to the ground".

- Javed Ahmad Ghamidi. The Rituals of Hajj and ‘Umrah Archived 7 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Mizan, Al-Mawrid

- "History of the Kaba".

- Central Bank of Iran. Banknotes & Coins: 2000 Rials. – Retrieved on 24 March 2009.

- Peterson, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. London: Routledge. Archived from the original on 20 May 2010.

- Hawting, G.R.; Kaʿba. Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an p. 76

- "Saudi Arabia's Top Artist Ahmad bin Ibrahim Passes Away". Khaleej Times. 9 November 2009. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- According to Muslim tradition: "God made the stone under Ibrahim's feet into something like clay so that his feet sunk into it. That was a miracle. It was transmitted on the authority of Abu Ja'far al-Baqir (may peace be upon him) that he said: Three stones were sent down from the Garden: the Station of Ibrahim, the rock of the children of Israel, and the Black Stone, which God entrusted Ibrahim with as a white stone. It was whiter than paper, but became black from the sins of the children of Adam." (The Hajj, F.E. Peters 1996)

- "'House of God' Kaaba gets new cloth". The Age Company Ltd. 2003. Retrieved 17 August 2006.

- "The Kiswa – (Kaaba Covering)". Al-Islaah Publications. Archived from the original on 22 July 2003. Retrieved 17 August 2006.

- Porter, Venetia (2012). "Textiles of Mecca and Medina". In Porter, Venetia (ed.). Hajj : journey to the heart of Islam. Cambridge, Mass.: The British Museum. pp. 257–258. ISBN 978-0-674-06218-4. OCLC 709670348.

- Porter, Venetia (2012). "Textiles of Mecca and Medina". In Porter, Venetia (ed.). Hajj : journey to the heart of Islam. Cambridge, Mass.: The British Museum. pp. 257–258. ISBN 978-0-674-06218-4. OCLC 709670348.

- Ghazal, Rym (28 August 2014). "Woven with devotion: the sacred Islamic textiles of the Kaaba". The National. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Nassar, Nahla (2013). "Dar al-Kiswa al-Sharifa: Administration and Production". In Porter, Venetia; Saif, Liana (eds.). The Hajj : collected essays. London: The British Museum. pp. 176–178. ISBN 978-0-86159-193-0. OCLC 857109543.

- Key to numbered parts translated from, accessed 2 December

- Clive L. N. Ruggles (2005). Ancient astronomy: an encyclopedia of cosmologies and myth (Illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-85109-477-6.

- Dick Teresi (2003). Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science—from the Babylonians to the Maya (Reprint, illustrated ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-7432-4379-7.

- Wright, Lyn. Kramer, John. Fusco, Angela. (2012), Dad's house, mom's house, National Film Board of Canada, OCLC 812009749CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- The Basis for the Building Work of God p. 37, Witness Lee, 2003

- Al-Muwatta Of Iman Malik Ibn Ana, p. 186, Anas, 2013

- Ruqaiyyah Maqsood, World Faiths, teach yourself – Islam, p. 76, ISBN 0-340-60901-X

- Shariati, Ali (2005). HAJJ: Reflection on Its Rituals. Islamic Publications International. ISBN 1-889999-38-5.

- Denny, Frederick Mathewson (2010). An Introduction to Islam. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13814477-7.

- Mohamed, Mamdouh N. (1996). Hajj to Umrah: From A to Z. Mamdouh Mohamed. ISBN 0-915957-54-X.

- "الرسول شرّف بني شيبة بحمل مفتاح الكعبة حتى قيام الساعة". Al Khaleej.

- "Kaaba". Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- "This is how the Kaaba is washed". Al Arabiya English. 17 October 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Karen (2000,2002). Islam: A Short History. ISBN 0-8129-6618-X.

- Crone, Patricia (2004). Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias.

- Elliott, Jeri (1992). Your Door to Arabia. ISBN 0-473-01546-3.

- Guillaume, A. (1955). The Life of Muhammad. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grunebaum, G. E. von (1970). Classical Islam: A History 600 A.D. to 1258 A.D.. Aldine Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-202-30767-1.

- Hawting, G.R; Kaʿba. Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān

- Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi The book of Idols, translated with introduction and notes by Nabih Amin Faris 1952

- Macaulay-Lewis, Elizabeth, The Kaba (text), Smarthistory.

- Mohamed, Mamdouh N. (1996). Hajj to Umrah: From A to Z. Amana Publications. ISBN 0-915957-54-X.

- Peterson, Andrew (1997). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture London: Routledge.

- Wensinck, A. J; Kaʿba. Encyclopaedia of Islam IV

- [1915] The Book of History, a History of All Nations From the Earliest Times to the Present, Viscount Bryce (Introduction), The Grolier Society.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article "Kaaba". |