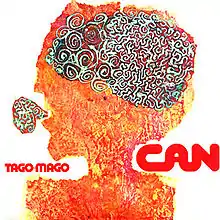

Tago Mago

Tago Mago is the second studio album by the German krautrock band Can, originally released as a double LP in 1971 on the United Artists label. It was the band's first album to feature Damo Suzuki after the 1970 departure of previous vocalist Malcolm Mooney.[5] Recorded in a rented castle near Cologne, the album features long-form experimental tracks blending funk rhythms, avant-garde noise, jazz improvisation, and electronic tape editing techniques.

| Tago Mago | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | February 1971 | |||

| Recorded | November 1970 February 1971 at Schloss Nörvenich, near Köln, West Germany | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 73:27 | |||

| Label | United Artists | |||

| Producer | Can | |||

| Can chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Alternative cover | ||||

Original UK cover and 40th anniversary edition | ||||

Tago Mago has been described as Can's best and most extreme record in sound and structure.[6] The album has received much critical acclaim since its release and has been cited as an influence by various artists. Drowned in Sound called it "arguably the most influential rock album ever recorded."[7]

Recording and production

After Malcolm Mooney left Can in 1970 the band was left without a vocalist.[8] Bassist Holger Czukay happened to meet Kenji "Damo" Suzuki when the latter was busking outside a cafe in Munich.[9] He introduced himself as a member of an experimental rock band and invited Suzuki to join them.[10] That evening, Suzuki performed with the band at the "Blow Up Club" and subsequently became a member of Can.[11]

Tago Mago was recorded in 1971 by Czukay in Schloss Nörvenich, a castle near Cologne.[12] Early in 1968 the band had been invited to stay there for a year without paying rent by the art collector Christoph Vohwinkel, who had rented the castle with the idea of transforming it into an art centre.[13]

Recording took three months to complete,[14] with sessions often lasting up to sixteen hours a day.[15] Czukay would edit these long, disorganized jams into structured songs.[16] Czukay used only two two-track tape recorders to capture the sessions.[15] Because of the limits of two-track recording the group favoured the castle's high-ceilinged entrance hall, an architectural reverb chamber, using the natural acoustics and placing the microphones optimally relative to their instruments.[17] Due to the intense reverberation, Czukay took advantage of the sonic bleed and limited the band to three microphones, shared between vocalist Damo Suzuki and drummer Jaki Liebezeit.[15] Keyboardist Irmin Schmidt experimented with sine-wave generators and oscillators in place of typical synthesizers on "Aumgn".[15]

This was the first of Can's albums to be made from not only regularly recorded music, but combined "in-between-recordings", where Czukay secretly recorded the musicians jamming during pre-production sessions.[10] Additionally, Czukay captured in-between-recordings of the shouts of a child who mistakenly burst into the room during recording, as well as the howling from a dog belonging to Vohwinkel.[15]

According to Czukay, the album was named after Illa de Tagomago, an island off the east coast of Ibiza.[18]

It was originally released as a double LP in 1971 by United Artists Records.

Music

Julian Cope wrote in Krautrocksampler that Tago Mago "sounds only like itself, like no-one before or after", and described the lyrics as delving "below into the Unconscious".[14] Dummy called it "a genre-defining work of psychedelic, experimental rock music."[3] Critic Simon Reynolds described the record's sound as "shamanic avant-funk."[2] Tago Mago finds Can changing to a jazzier and more experimental sound than previous recordings, with longer instrumental interludes and fewer vocals; this shift was caused by the dramatic difference between Suzuki and the band's more dominant ex-singer Mooney.[19] On the album, Can took sonic inspiration from sources as diverse as jazz musicians such as Miles Davis and from electronic avant-garde music.[20] The album was also inspired by the occultist Aleister Crowley, which is reflected through the dark sound of the album as well as being named after Illa de Tagomago, an island which features in the Crowley legend.[4] Czukay reflects that the album was "an attempt in achieving a mystery musical world from light to darkness and return".[10] The group has referred to the album as their "magic record".[4] The tracks have been described as having an "air of mystery and forbidden secrets".[9] Tago Mago is divided into two LPs, the first of which is more conventional and structured and the second more experimental and free-form.[21]

"Paperhouse", the opening track, is one of the shorter songs on the album. Allmusic critic Ned Raggett depicted the song as "beginning with a low-key chime and beat, before amping up into a rumbling roll in the midsection, then calming down again before one last blast."[1] "Mushroom" is the following track, which Leone noted as having a darker sound than the previous song. "Oh Yeah" and "Halleluhwah" contain the elements that have been referred to as Can's "trademark" sound: "Damo Suzuki's vocals, which shift from soft mumbles to aggressive outbursts without warning; Jaki Liebezeit's manic drumming; Holger Czukay's production manipulations (e.g. the backwards vocals and opening sound effects on 'Oh Yeah')."[22] Both "Oh Yeah" and "Halleluhwah" use repetitive grooves.[23]

The second LP features Can's more avant-garde efforts, with Roni Sarig, author of The Secret History of Rock calling it "as close as it ever got to avant-garde noise music."[6] Featuring Holger Czukay’s tape and radio experiments, the tracks "Aumgn" and "Peking O" have led music critics to write that Tago Mago is Can's "most extreme record in terms of sound and structure."[6] "Peking O" made early use of a drum machine, an Ace Tone Rhythm Ace, combined with acoustic drumming.[24] "Aumgn" features keyboardist Irmin Schmidt chanting rather than Suzuki's vocals.[19] The closing track, "Bring Me Coffee or Tea", was described by Raggett as a "coda to a landmark record."[1]

The side-long track "Halleluhwah" was shortened from 18½ to 3½ minutes for the B-side of the single "Turtles Have Short Legs", a novelty song recorded during the Tago Mago sessions and released by Liberty Records in 1971.[25] A different, 5½-minute shortened version of "Halleluhwah" would later appear on the compilation Cannibalism in 1978 while the single's A-side remained out-of-print until its inclusion on 1992's Cannibalism 2.

Reception & legacy

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 99/100[7] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Drowned in Sound | 10/10[26] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Filter | 95%[7] |

| Pitchfork | 9.3/10 (2004)[28] 10/10 (2011; 40th Anniversary Edition)[29] |

| Record Collector | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 9/10[31] |

| Stylus | B[32] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Uncut | |

Tago Mago has been critically acclaimed and is credited with pioneering various modern musical styles. Raggett called Tago Mago a "rarity of the early '70s, a double album without a wasted note".[1] Many critics, particularly in the UK,[35] were eager to praise the album, and by the end of 1971 Can played their first show in the UK.[12]

Influence

Various artists have cited Tago Mago as an influence on their work. John Lydon of the Sex Pistols and Public Image Ltd. called it "stunning" in his autobiography Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs.[36] Bobby Gillespie of Jesus and Mary Chain and Primal Scream said "The music was like nothing I'd ever heard before, not American, not rock & roll but mysterious and European."[37] Mark Hollis of Talk Talk made reference to Tago Mago as "an extremely important album" and an inspiration to his own Laughing Stock.[38] Marc Bolan listed Suzuki's freeform lyricism as an inspiration.[39] Jonny Greenwood and Thom Yorke of Radiohead cite the album as an early influence.[40]

There have been attempts by several artists to play cover versions of songs from Tago Mago. The Flaming Lips album In a Priest Driven Ambulance contains a song called "Take Meta Mars", which was an attempt at covering the song "Mushroom". However, the band members had only heard the song once and didn't have a copy of it at the time, so the song is only similar-sounding and not a proper cover.[41] The Jesus and Mary Chain have covered the song live and included it on the CD version of Barbed Wire Kisses. The Fall recorded a song indebted to the Tago Mago track "Oh Yeah" entitled "I Am Damo Suzuki", on 1985's This Nation's Saving Grace.

Remix versions of several Tago Mago tracks by various artists are included on the album Sacrilege.

Accolades

In addition to the ones below, the album is listed in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die which states, "Even after 30 years Tago Mago sounds refreshingly contemporary and gloriously extreme."[42] As of November 2020, Acclaimed Music finds it to be the 243rd most acclaimed album of all time.[43]

| Publication/Source | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pitchfork | "Top 100 Albums of the 1970s" | 2004 | 29[44] |

| Uncut | "200 Greatest Albums of All Time" | 2016 | 88[45] |

| NME | "NME's The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time" | 2013 | 409[46] |

| "Some of the Greatest Double LPs Ever Issued" | 1991 | 21[47] | |

| Sounds | "The 100 Best Albums of All Time" | 1986 | 51[48] |

| Mojo | "The 100 Records That Changed the World" | 2007 | 62[49] |

| The Guardian | "1000 Albums to Hear Before You Die" | 2007 | -[50] |

| Tom Moon | "1,000 Recordings to Hear Before You Die" | 2008 | -[51] |

Track listing

All tracks are written by Holger Czukay, Michael Karoli, Jaki Liebezeit, Irmin Schmidt and Damo Suzuki.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Paperhouse" | 7:28 |

| 2. | "Mushroom" | 4:03 |

| 3. | "Oh Yeah" | 7:23 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Halleluhwah" | 18:32 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Aumgn" | 17:37 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Peking O" | 11:37 |

| 2. | "Bring Me Coffee or Tea" | 6:47 |

| Total length: | 73:27 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Mushroom (Live 1972)" | 8:42 |

| 2. | "Spoon (Live 1972)" | 29:55 |

| 3. | "Halleluhwah (Live 1972)" | 9:12 |

| Total length: | 47:49 | |

Personnel

- Damo Suzuki – vocals

- Holger Czukay – bass, engineering, editing

- Michael Karoli – guitar, violin

- Jaki Liebezeit – drums, double bass, piano

- Irmin Schmidt – organ, electric piano, oscillators; vocals on "Aumgn"

Production

- U. Eichberger – original artwork & design

- Andreas Torkler – design (2004 rerelease)

References

- Raggett, Ned. "Tago Mago". Allmusic Guide. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- Reynolds, Simon (1995). "Krautrock Reissues". Melody Maker. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- "Can's ground-breaking album 'Tago Mago' is getting a re-release ". Dummy Mag. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- DeRogatis, Jim (2003). Turn On Your Mind: Four Decades of Great Psychedelic Rock. Hal Leonard. p. 273. ISBN 0-634-05548-8.

- "Music". Malcolm Mooney. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- Sarig, Roni (1998). The Secret History of Rock: The Most Influential Bands You'Ve Never Heard. Watson-Guptill Publications. p. 125. ISBN 0-8230-7669-5.

- "Tago Mago [40th Anniversary Edition] - Can". Metacritic.

- Stubbs, David. "CAN - Tago Mago". CAN remastered - Tago Mago (CD liner notes). September 2004.

- DeRogatis, Jim. "Then I Saw Mushroom Head: The Story of Can". Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- Czukay, Holger. "A Short History of The Can - Discography". Perfect Sound Forever. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- Smith, Gary. "CAN Biography". Spoon Records. Archived from the original on 2011-10-30. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- Mute Records. "Biography". Mute Records. Archived from the original on 2008-12-20. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- Rob Young; Irmin Schmidt (2018). All Gates Open: The Story of Can. London: Faber & Faber. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-0-571-31151-4.

- Cope, p. 55

- Bell, Max (April 11, 2018). "Can: The making of landmark album Tago Mago". Louder. Louder. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- Cope, p. 57

- Rob Young; Irmin Schmidt (2018). All Gates Open: The Story of Can. London: Faber & Faber. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-571-31151-4.

- Damon Krukowski (1998). "Can interview". Ptolemaic Terrascope. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- Cope, p. 56

- Manning, Peter D. (2003). Electronic and Computer Music. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. p. 174. ISBN 0-19-517085-7.

- Thompson, Dave (2000). Alternative Rock: The Best Musicians and Recordings. Backbeat Books. p. 60. ISBN 0-87930-607-6.

- McGlinchey, Joe. "Tago Mago". Ground & Sky. Archived from the original on 2003-01-30. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- Unterberger, Ritchie (1998). Unknown Legends of Rock 'n' Roll: Psychederic Unknowns, Mad Geniuses, Punk Pioneers, Lo-Fi Mavericks, and More. Backbeat Books. p. 170. ISBN 0-87930-534-7.

- Rick Moody, On Celestial Music: And Other Adventures in Listening, page 202, Hachette

- Metzger, Richard. "'Turtles Have Short Legs': Can's Idea of a Krautrock Novelty Song?". Dangerous Minds. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Dan Lucas (24 November 2011). "Tago Mago 40th Anniversary Edition". Drowned in Sound. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). "Can". Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 0857125958.

- Leone, Dominique (10 November 2004). "Album Review: Can: Monster Movie / Soundtracks / Tago Mago / Ege Bamyasi". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- Wolk, Douglas (9 December 2011). "Can: Tago Mago [40th Anniversary Edition] | Album Reviews | Pitchfork". pitchfork.com. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- "CAN - TAGO MAGO". Record Collector. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig, eds. (1995). "Can". Spin Alternative Record Guide (1st ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- Ramsay, J T. (7 January 2005). "Can - Tago Mago / Ege Bamyasi". Stylus. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- Nathan Brackett; Christian David Hoard (2004). The new Rolling Stone album guide. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-7432-0169-8.

- Cavanagh, David. "CAN - TAGO MAGO R1971 - Review - Uncut.co.uk". uncut.co.uk. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- Thompson, Dave (2000). Eurock: European Rock and the Second Culture. Eurorock. p. 33. ISBN 0-9723098-0-2.

- Lydon, John (1995). Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs. Picador. p. 81. ISBN 0-312-11883-X.

- Gillespie, Bobby. "CAN - Tago Mago". CAN remastered - Tago Mago (CD liner notes). September 2004.

- Stubbs, David (February 1998). "Talking Liberties". Vox.

- Bolan, Marc. Interview by Russell Harty. London Weekend Television. 23 Jul. 1972

- Griffiths, Dai (2004). OK Computer (331⁄3 series). Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0-8264-1663-2.

- Coyne, Wayne (1990). Album notes for In a Priest Driven Ambulance by The Flaming Lips, [CD booklet]. Restless Records.

- Shade, Chris (2005). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. Quintet Publishing Limited. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-7333-2120-7.

- "Acclaimed Music". www.acclaimedmusic.net. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "The 100 Best Albums of the 1970s". Pitchfork. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "Rocklist.net..Rocklist.net... Uncut Lists ." www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time: 500-401 | NME". NME Music News, Reviews, Videos, Galleries, Tickets and Blogs | NME.COM. 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "Rocklist.net....Various NME Lists..." www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "Rocklist.net...Sounds - Sounds all time top 100's". www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "Rocklist.net...Mojo Lists..." www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- Guardian Staff (2007-11-17). "Artists beginning with C (part 1)". the Guardian. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- "Rocklist.net...Steve Parker...Tom Moon 1000." www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

Further reading

- Cope, Julian (1995). Krautrocksampler. Head Heritage. ISBN 0-9526719-1-3.

- Warner, Alan (2015). Tago Mago: Permission to Dream. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-6289-2108-3. ePDF and ePub editions are also available.