Taiwanese indigenous peoples

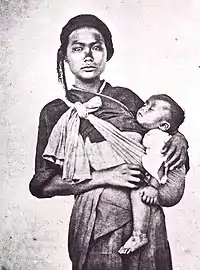

Taiwanese indigenous peoples or formerly Taiwanese aborigines, Formosan people, Austronesian Taiwanese[2][3] or Gāoshān people,[4] are the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, who number almost 569,008 or 2.38% of the island's population—or more than 800,000 people, considering the potential recognition of Taiwanese plain indigenous peoples officially in the future. Recent research suggests their ancestors may have been living on Taiwan for approximately 5,500 years in relative isolation before major Han (Chinese) immigration from mainland China began in the 17th century.[5] Taiwanese indigenous peoples are Austronesian peoples, with linguistic and genetic ties to other Austronesian peoples.[6] Related ethnic groups include Polynesians, most people of the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei, among others. The demographic proportion in Singapore is similar to Taiwan, with the Han Chinese making up a majority of the population at 76% and the Austronesian (Malays) a minority, albeit at a higher percentage of 15% with other races making up the difference.[7] The consensus among the scientific community points to Polynesians also having originated from the indigenous Taiwanese through linguistic and genetic ties.[8][9]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 574,508 or 2.38% of the population of Taiwan (Non-status indigenous peoples excluded) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Taiwan | |

| Languages | |

| Atayal, Bunun, Amis, Paiwan, other Formosan languages. Han languages (Mandarin, Hokkien, Hakka) | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Christianity, minority Animism[1] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Taiwanese people, other Austronesians |

| Taiwanese indigenous peoples | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 臺灣原住民族 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台湾原住民族 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Taiwanese original inhabitants | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taiwanese indigenous peoples |

|---|

|

| Peoples |

|

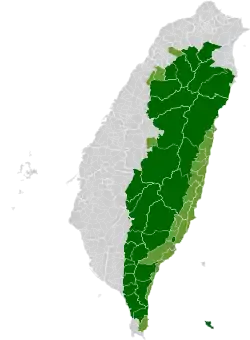

Nationally Recognized Locally recognized Unrecognized |

| Related topics |

For centuries, Taiwan's indigenous inhabitants experienced economic competition and military conflict with a series of colonising newcomers. Centralised government policies designed to foster language shift and cultural assimilation, as well as continued contact with the colonisers through trade, inter-marriage and other intercultural processes, have resulted in varying degrees of language death and loss of original cultural identity. For example, of the approximately 26 known languages of the Taiwanese indigenous peoples (collectively referred to as the Formosan languages), at least ten are now extinct, five are moribund[10] and several are to some degree endangered. These languages are of unique historical significance, since most historical linguists consider Taiwan to be the original homeland of the Austronesian language family.[5]

Taiwan's Austronesian speakers were formerly distributed over much of the island's rugged Central Mountain Range and were concentrated in villages along the alluvial plains. The bulk of contemporary Taiwanese indigenous peoples now live in the mountains and in cities.

The indigenous peoples of Taiwan have economic and social deficiencies, including a high unemployment rate and substandard education. Since the early 1980s, many indigenous groups have been actively seeking a higher degree of political self-determination and economic development.[11] The revival of ethnic pride is expressed in many ways by the indigenous peoples, including the incorporation of elements of their culture into commercially successful pop music. Efforts are under way in indigenous communities to revive traditional cultural practices and preserve their traditional languages. The Austronesian Cultural Festival in Taitung City is one means by which community members promote indigenous culture. In addition, several indigenous communities have become extensively involved in the tourism and ecotourism industries with the goal of achieving increased economic self-reliance and preserving their culture.[12]

Terminology

For most of their recorded history, Taiwanese aborigines have been defined by the agents of different Confucian, Christian and Nationalist "civilizing" projects, with a variety of aims. Each "civilizing" project defined the aborigines based on the "civilizer's" cultural understandings of difference and similarity, behavior, location, appearance and prior contact with other groups of people.[13] Taxonomies imposed by colonizing forces divided the aborigines into named subgroups, referred to as "tribes". These divisions did not always correspond to distinctions drawn by the aborigines themselves. However, the categories have become so firmly established in government and popular discourse over time that they have become de facto distinctions, serving to shape in part today's political discourse within the Republic of China (ROC), and affecting Taiwan's policies regarding indigenous peoples.

The Han sailor, Chen Di, in his Record of the Eastern Seas (1603), identifies the indigenous people of Taiwan as simply "Eastern Savages" (東番; Dongfan), while the Dutch referred to Taiwan's original inhabitants as "Indians" or "blacks", based on their prior colonial experience in what is currently Indonesia.[14]

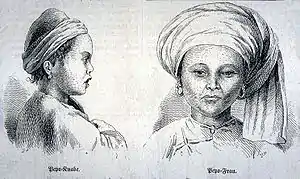

Beginning nearly a century later, as the rule of the Qing Empire expanded over wider groups of people, writers and gazetteers recast their descriptions away from reflecting degree of acculturation, and toward a system that defined the aborigines relative to their submission or hostility to Qing rule. Qing used the term "raw/wild/uncivilized" (生番) to define those people who had not submitted to Qing rule, and "cooked/tamed/civilized" (熟番) for those who had pledged their allegiance through their payment of a head tax.[note 1] According to the standards of the Qianlong Emperor and successive regimes, the epithet "cooked" was synonymous with having assimilated to Han cultural norms, and living as a subject of the Empire, but it retained a pejorative designation to signify the perceived cultural lacking of the non-Han people.[16][17] This designation reflected the prevailing idea that anyone could be civilized/tamed by adopting Confucian social norms.[18][19]

As the Qing consolidated their power over the plains and struggled to enter the mountains in the late 19th century, the terms Pingpu (平埔族; Píngpǔzú; 'Plains peoples') and Gaoshan (高山族; Gāoshānzú; 'High Mountain peoples') were used interchangeably with the epithets "civilized" and "uncivilized".[20] During Japanese rule (1895–1945), anthropologists from Japan maintained the binary classification. In 1900 they incorporated it into their own colonial project by employing the term Peipo (平埔) for the "civilized tribes", and creating a category of "recognized tribes" for the aborigines who had formerly been called "uncivilized". The Musha Incident of 1930 led to many changes in aboriginal policy, and the Japanese government began referring to them as Takasago-zoku (高砂族).[21] The latter group included the Atayal, Bunun, Tsou, Saisiat, Paiwan, Puyuma, and Amis peoples. The Tao (Yami) and Rukai were added later, for a total of nine recognized peoples.[22] During the early period of Chinese Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) rule the terms Shandi Tongbao (山地同胞) "mountain compatriots" and Pingdi Tongbao (平地同胞) "plains compatriots" were invented, to remove the presumed taint of Japanese influence and reflect the place of Taiwan's indigenous people in the Chinese Nationalist state.[23] The KMT later adopted the use of all the earlier Japanese groupings except Peipo.

Despite recent changes in the field of anthropology and a shift in government objectives, the Pingpu and Gaoshan labels in use today maintain the form given by the Qing to reflect aborigines' acculturation to Han culture. The current recognized aborigines are all regarded as Gaoshan, though the divisions are not and have never been based strictly on geographical location. The Amis, Saisiat, Tao and Kavalan are all traditionally Eastern Plains cultures.[24] The distinction between Pingpu and Gaoshan people continues to affect Taiwan's policies regarding indigenous peoples, and their ability to participate effectively in government.[25]

Although the ROC's Government Information Office officially lists 16 major groupings as "tribes," the consensus among scholars maintains that these 16 groupings do not reflect any social entities, political collectives, or self-identified alliances dating from pre-modern Taiwan.[26] The earliest detailed records, dating from the Dutch arrival in 1624, describe the aborigines as living in independent villages of varying size. Between these villages there was frequent trade, intermarriage, warfare and alliances against common enemies. Using contemporary ethnographic and linguistic criteria, these villages have been classed by anthropologists into more than 20 broad (and widely debated) ethnic groupings,[27][28] which were never united under a common polity, kingdom or "tribe".[29]

| Atayal | Saisiyat | Bunun | Tsou | Rukai | Paiwan | Puyuma | Amis | Yami | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27,871 | 770 | 16,007 | 2,325 | 13,242 | 21,067 | 6,407 | 32,783 | 1,487 | 121,950 |

Since 2005, some local governments, including Tainan City in 2005, Fuli, Hualien in 2013, and Pingtung County in 2016, have begun to recognize Taiwanese Plain Indigenous peoples. The numbers of people who have successfully registered, including Kaohsiung City Government that has opened to register but not yet recognized, as of 2017 are:[31][32][33][34]

| Siraya | Taivoan | Makatao | Not Specific | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tainan | 11,830 | - | - | – | 11,830 |

| Kaohsiung | 107 | 129 | – | 237 | 473 |

| Pingtung | – | – | 1,803 | 205 | 2,008 |

| Fuli, Hualien | – | – | – | 100 | 100 |

| Total | 11,937 | 129 | 1,803 | 542 | 14,411 |

Recognized peoples

Indigenous ethnic groups recognized by Taiwan

The Government of the Republic of China officially recognizes distinct people groups among the indigenous community based upon the qualifications drawn up by the Council of Indigenous Peoples (CIP).[35] To gain this recognition, communities must gather a number of signatures and a body of supporting evidence with which to successfully petition the CIP. Formal recognition confers certain legal benefits and rights upon a group, as well as providing them with the satisfaction of recovering their separate identity as an ethnic group. As of June 2014, 16 people groups have been recognized.[36]

The Council of Indigenous Peoples consider several limited factors in a successful formal petition. The determining factors include collecting member genealogies, group histories and evidence of a continued linguistic and cultural identity.[37][38] The lack of documentation and the extinction of many indigenous languages as the result of colonial cultural and language policies have made the prospect of official recognition of many ethnicities a remote possibility. Current trends in ethno-tourism have led many former Plains Aborigines to continue to seek cultural revival.[39]

Among the Plains groups that have petitioned for official status, only the Kavalan and Sakizaya have been officially recognized. The remaining twelve recognized groups are traditionally regarded as mountain aboriginals.

Other indigenous groups or subgroups that have pressed for recovery of legal aboriginal status include Chimo (who have not formally petitioned the government, see Lee 2003), Kakabu, Makatao, Pazeh, Siraya,[40] and Taivoan. The act of petitioning for recognized status, however, does not always reflect any consensus view among scholars that the relevant group should in fact be categorized as a separate ethnic group. The Siraya will become the 17th ethnic group to be recognized once their status, already recognized by the courts in May 2018, is officially announced by the central government.[41]

There is discussion among both scholars and political groups regarding the best or most appropriate name to use for many of the people groups and their languages, as well as the proper romanization of that name. Commonly cited examples of this ambiguity include (Seediq/Sediq/Truku/Taroko) and (Tao/Yami).

Nine people groups were originally recognized before 1945 by the Japanese government.[35] The Thao, Kavalan and Truku were recognized by Taiwan's government in 2001, 2002 and 2004 respectively. The Sakizaya were recognized as a 13th on 17 January 2007,[42] and on 23 April 2008 the Sediq were recognized as Taiwan's 14th official ethnic group.[43] Previously the Sakizaya had been listed as Amis and the Sediq as Atayal. Hla'alua and Kanakanavu were recognized as the 15th and 16th ethnic group on 26 June 2014.[36] A full list of the recognized ethnic groups of Taiwan, as well as some of the more commonly cited unrecognized peoples, is as follows:

- Recognized: Ami, Atayal, Bunun, Hla'alua, Kanakanavu, Kavalan, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Saisiyat, Tao, Thao, Tsou, Truku, Sakizaya and Sediq.

- Locally recognized: Makatao (in Pingtung and Fuli), Siraya (in Tainan and Fuli), Taivoan (in Fuli)

- Unrecognized: Babuza, Basay, Hoanya, Ketagalan, Luilang, Pazeh/Kaxabu, Papora, Qauqaut, Taokas, Trobiawan.

Taiwanese aborigines in China

The People's Republic of China (PRC) government claims Taiwan as part of its territory and officially refers to all Taiwanese aborigines as Gāoshān (lit. "high mountain") and recognize them as one of the 56 ethnicities officially. According to the 2000 Census, 4,461 people were identified as Gāoshān living in mainland China. Some surveys indicate that of the 4,461 Gāoshān recorded in the 2000 PRC Census, it is estimated that there are 1,500 Amis, 1,300 Bunun, 510 Paiwan, and the remainder belonging to other peoples.[4] They are descendants of the indigenous peoples of Taiwan who were in mainland China during the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949.[4]

Assimilation and acculturation

Archaeological, linguistic and anecdotal evidence suggests that Taiwan's indigenous peoples have undergone a series of cultural shifts to meet the pressures of contact with other societies and new technologies.[44] Beginning in the early 17th century, Taiwanese aborigines faced broad cultural change as the island became incorporated into the wider global economy by a succession of competing colonial regimes from Europe and Asia.[45][46] In some cases groups of aborigines resisted colonial influence, but other groups and individuals readily aligned with the colonial powers. This alignment could be leveraged to achieve personal or collective economic gain, collective power over neighboring villages or freedom from unfavorable societal customs and taboos involving marriage, age-grade and child birth.[47][48]

Particularly among the Plains Aborigines, as the degree of the "civilizing projects" increased during each successive regime, the aborigines found themselves in greater contact with outside cultures. The process of acculturation and assimilation sometimes followed gradually in the wake of broad social currents, particularly the removal of ethnic markers (such as bound feet, dietary customs and clothing), which had formerly distinguished ethnic groups on Taiwan.[49] The removal or replacement of these brought about an incremental transformation from "Fan" (barbarian) to the dominant Confucian "Han" culture.[50] During the Japanese and KMT periods centralized modernist government policies, rooted in ideas of Social Darwinism and culturalism, directed education, genealogical customs and other traditions toward ethnic assimilation.[51][52]

Within the Taiwanese Han Hoklo community itself, differences in culture indicate the degree to which mixture with aboriginals took place, with most pure Hoklo Han in Northern Taiwan having almost no Aboriginal admixture, which is limited to Hoklo Han in Southern Taiwan.[53] Plains aboriginals who were mixed and assimilated into the Hoklo Han population at different stages were differentiated by the historian Melissa J. Brown between "short-route" and "long-route".[54] The ethnic identity of assimilated Plains Aboriginals in the immediate vicinity of Tainan was still known since a pure Hoklo Taiwanese girl was warned by her mother to stay away from them.[55] The insulting name "fan" was used against Plains Aborigines by the Taiwanese, and the Hoklo Taiwanese speech was forced upon Aborigines like the Pazeh.[56] Hoklo Taiwanese has replaced Pazeh and driven it to near extinction.[57] Aboriginal status has been requested by Plains Aboriginals.[58]

Current forms of assimilation

Many of these forms of assimilation are still at work today. For example, when a central authority nationalizes one language, that attaches economic and social advantages to the prestige language. As generations pass, use of the indigenous language often fades or disappears, and linguistic and cultural identity recede as well. However, some groups are seeking to revive their indigenous identities.[59] One important political aspect of this pursuit is petitioning the government for official recognition as a separate and distinct ethnic group.

The complexity and scope of aboriginal assimilation and acculturation on Taiwan has led to three general narratives of Taiwanese ethnic change. The oldest holds that Han migration from Fujian and Guangdong in the 17th century pushed the Plains Aborigines into the mountains, where they became the Highland peoples of today.[60] A more recent view asserts that through widespread intermarriage between Han and aborigines between the 17th and 19th centuries, the aborigines were completely Sinicized.[61][62] Finally, modern ethnographical and anthropological studies have shown a pattern of cultural shift mutually experienced by both Han and Plains Aborigines, resulting in a hybrid culture. Today people who comprise Taiwan's ethnic Han demonstrate major cultural differences from Han elsewhere.[63][39]

Within the Taiwanese Han Hoklo community itself, differences in culture indicate the degree to which mixture with aboriginals took place, with most Hoklo Han in Northern Taiwan having almost no Aboriginal admixture, which is limited to Hoklo Han in Southern Taiwan.[64] Plains aboriginals who were mixed and assimilated into the Hoklo Han population at different stages were differentiated by the historian Melissa J. Brown between "short-route" and "long-route".[65]

Surnames and identity

Several factors encouraged the assimilation of the Plains Aborigines.[note 2] Taking a Han name was a necessary step in instilling Confucian values in the aborigines.[67] Confucian values were necessary to be recognized as a full person and to operate within the Confucian Qing state.[68] A surname in Han society was viewed as the most prominent legitimizing marker of a patrilineal ancestral link to the Yellow Emperor (Huang Di) and the Five Emperors of Han mythology.[69] Possession of a Han surname, then, could confer a broad range of significant economic and social benefits upon aborigines, despite a prior non-Han identity or mixed parentage. In some cases, members of Plains Aborigines adopted the Han surname Pan (潘) as a modification of their designated status as Fan (番: "barbarian").[70] One family of Pazeh became members of the local gentry.[71][72] complete with a lineage to Fujian province. In other cases, families of Plains Aborigines adopted common Han surnames, but traced their earliest ancestor to their locality in Taiwan.

In many cases, large groups of immigrant Han would unite under a common surname to form a brotherhood. Brotherhoods were used as a form of defense, as each sworn brother was bound by an oath of blood to assist a brother in need. The brotherhood groups would link their names to a family tree, in essence manufacturing a genealogy based on names rather than blood, and taking the place of the kinship organizations commonly found in China. The practice was so widespread that today's family books are largely unreliable.[68][73] Many Plains Aborigines joined the brotherhoods to gain protection of the collective as a type of insurance policy against regional strife, and through these groups they took on a Han identity with a Han lineage.

The degree to which any one of these forces held sway over others is unclear. Preference for one explanation over another is sometimes predicated upon a given political viewpoint. The cumulative effect of these dynamics is that by the beginning of the 20th century the Plains Aborigines were almost completely acculturated into the larger ethnic Han group, and had experienced nearly total language shift from their respective Formosan languages to Chinese. In addition, legal barriers to the use of traditional surnames persisted until the 1990s, and cultural barriers remain. Aborigines were not permitted to use their traditional names on official identification cards until 1995 when a ban on using aboriginal names dating from 1946 was finally lifted.[74] One obstacle is that household registration forms allow a maximum of 15 characters for personal names. However, aboriginal names are still phonetically translated into Chinese characters, and many names require more than the allotted space.[75]

History of the aboriginal peoples

Taiwanese aborigines are Austronesian peoples, with linguistic and genetic ties to other Austronesian ethnic groups, such as peoples of the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Madagascar and Oceania.[76][77] Chipped-pebble tools dating from perhaps as early as 15,000 years ago suggest that the initial human inhabitants of Taiwan were Paleolithic cultures of the Pleistocene era. These people survived by eating marine life. Archaeological evidence points to an abrupt change to the Neolithic era around 6,000 years ago, with the advent of agriculture, domestic animals, polished stone adzes and pottery. The stone adzes were mass-produced on Penghu and nearby islands, from the volcanic rock found there. This suggests heavy sea traffic took place between these islands and Taiwan at this time.[78]

In 2016, an extensive DNA analysis was carried out with the aim of providing a new solution to the long-standing problem inherent in attempting to reconcile a language family spread across so large a region with a community of speakers of such great genetic diversity. It showed that, while the haplogroup M7c3c genetic marker supported the "out-of-Taiwan" hypothesis, none of the other genetic markers did so. The results suggested that there had been two Neolithic waves of migration into the islands of South East Asia, but that both had been small-scale affairs. The first wave had reached as far as Eastern Indonesia and the Papuan population, but the impact of the second wave had been negligible outside the Philippines.[79] The authors argued that the disproportionately great cultural impact on indigenous populations was likely due to small-scale interactions and waves of acculturation, their strong influence on the language of these peoples being due to the Taiwanese migrants being perceived possibly as an elite or a group associated with a new religion or philosophy.[80][81][82]

The Austronesian speaking people can now be grouped into two genetically distinct groups:

- The Sunda or Malay-group consisting of most people in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Madagascar and historically Asian Mainland

- The Taiwanese-Polynesian group consisting of most people in Taiwan, northern Philippines, Polynesia, Micronesia and (historically) southern China.

Recorded history of the aborigines in Taiwan began around the 17th century, and has often been dominated by the views and policies of foreign powers and non-aborigines. Beginning with the arrival of Dutch merchants in 1624, the traditional lands of the aborigines have been successively colonized by Dutch, Spanish, Ming, Qing Dynasty, Japanese, and Republic of China rulers. Each of these successive "civilizing" cultural centers participated in violent conflict and peaceful economic interaction with both the Plains and Mountain indigenous groups. To varying degrees, they influenced or transformed the culture and language of the indigenous peoples.

Four centuries of non-indigenous rule can be viewed through several changing periods of governing power and shifting official policy toward aborigines. From the 17th century until the early 20th, the impact of the foreign settlers—the Dutch, Spanish and Han—was more extensive on the Plains peoples. They were far more geographically accessible than the Mountain peoples, and thus had more dealings with the foreign powers. The reactions of indigenous people to imperial power show not only acceptance, but also incorporation or resistance through their cultural practices [83][84] By the beginning of the 20th century, the Plains peoples had largely been assimilated into contemporary Taiwanese culture as a result of European and Han colonial rule. Until the latter half of the Japanese colonial era the Mountain peoples were not entirely governed by any non-indigenous polity. However, the mid-1930s marked a shift in the intercultural dynamic, as the Japanese began to play a far more dominant role in the culture of the Highland groups. This increased degree of control over the Mountain peoples continued during Kuomintang rule. Within these two broad eras, there were many differences in the individual and regional impact of the colonizers and their "civilizing projects". At times the foreign powers were accepted readily, as some communities adopted foreign clothing styles and cultural practices (Harrison 2003), and engaged in cooperative trade in goods such as camphor, deer hides, sugar, tea and rice.[85] At numerous other times changes from the outside world were forcibly imposed.

Much of the historical information regarding Taiwan's aborigines was collected by these regimes in the form of administrative reports and gazettes as part of greater "civilizing" projects. The collection of information aided in the consolidation of administrative control.

Plains aboriginals

The Plains Aborigines mainly lived in stationary village sites surrounded by defensive walls of bamboo. The village sites in southern Taiwan were more populated than other locations. Some villages supported a population of more than 1,500 people, surrounded by smaller satellite villages.[86] Siraya villages were constructed of dwellings made of thatch and bamboo, raised 2 m (6.6 ft) from the ground on stilts, with each household having a barn for livestock. A watchtower was located in the village to look out for headhunting parties from the Highland peoples. The concept of property was often communal, with a series of conceptualized concentric rings around each village. The innermost ring was used for gardens and orchards that followed a fallowing cycle around the ring. The second ring was used to cultivate plants and natural fibers for the exclusive use of the community. The third ring was for exclusive hunting and deer fields for community use. The Plains Aborigines hunted herds of spotted Formosan sika deer, Formosan sambar deer, and Reeves's muntjac as well as conducting light millet farming. Sugar and rice were grown as well, but mostly for use in preparing wine.[87]

Many of the Plains Aborigines were matrilineal/matrifocal societies. A man married into a woman's family after a courtship period during which the woman was free to reject as many men as she wished. In the age-grade communities, couples entered into marriage in their mid-30s when a man would no longer be required to perform military service or hunt heads on the battle-field. In the matriarchal system of the Siraya, it was also necessary for couples to abstain from marriage until their mid-30s, when the bride's father would be in his declining years and would not pose a challenge to the new male member of the household. It was not until the arrival of the Dutch Reformed Church in the 17th century that the marriage and child-birth taboos were abolished. There is some indication that many of the younger members of Sirayan society embraced the Dutch marriage customs as a means to circumvent the age-grade system in a push for greater village power.[88] Almost all indigenous peoples in Taiwan have traditionally had a custom of sexual division of labor. Women did the sewing, cooking and farming, while the men hunted and prepared for military activity and securing enemy heads in headhunting raids, which was a common practice in early Taiwan. Women were also often found in the office of priestesses or mediums to the gods.

For centuries, Taiwan's aboriginal peoples experienced economic competition and military conflict with a series of colonizing peoples. Centralized government policies designed to foster language shift and cultural assimilation, as well as continued contact with the colonizers through trade, intermarriage and other dispassionate intercultural processes, have resulted in varying degrees of language death and loss of original cultural identity. For example, of the approximately 26 known languages of the Taiwanese aborigines (collectively referred to as the Formosan languages), at least ten are extinct, five are moribund[10] and several are to some degree endangered. These languages are of unique historical significance, since most historical linguists consider Taiwan to be the original homeland of the Austronesian language family.[5]

Under Dutch rule

During the European period (1623–1662) soldiers and traders representing the Dutch East India Company maintained a colony in southwestern Taiwan (1624–1662) near present-day Tainan City. This established an Asian base for triangular trade between the company, the Qing Dynasty and Japan, with the hope of interrupting Portuguese and Spanish trading alliances with China. The Spanish also established a small colony in northern Taiwan (1626–1642) in present-day Keelung. However, Spanish influence wavered almost from the beginning, so that by the late 1630s they had already withdrawn most of their troops.[89] After they were driven out of Taiwan by a combined Dutch and aboriginal force in 1642, the Spanish "had little effect on Taiwan's history".[90] Dutch influence was far more significant: expanding to the southwest and north of the island, they set up a tax system and established schools and churches in many villages.

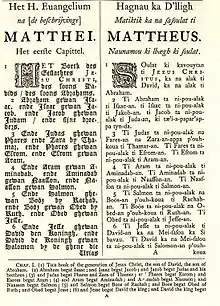

When the Dutch arrived in 1624 at Tayouan (Anping) Harbor, Siraya-speaking representatives from nearby Saccam village soon appeared at the Dutch stockade to barter and trade; an overture which was readily welcomed by the Dutch. The Sirayan villages were, however, divided into warring factions: the village of Sinckan (Sinshih) was at war with Mattau (Madou) and its ally Baccluan, while the village of Soulang maintained uneasy neutrality. In 1629 a Dutch expeditionary force searching for Han pirates was massacred by warriors from Mattau, and the victory inspired other villages to rebel.[91] In 1635, with reinforcements having arrived from Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia), the Dutch subjugated and burned Mattau. Since Mattau was the most powerful village in the area, the victory brought a spate of peace offerings from other nearby villages, many of which were outside the Siraya area. This was the beginning of Dutch consolidation over large parts of Taiwan, which brought an end to centuries of inter-village warfare.[92] The new period of peace allowed the Dutch to construct schools and churches aimed to acculturate and convert the indigenous population.[93][94] Dutch schools taught a romanized script (Sinckan writing), which transcribed the Siraya language. This script maintained occasional use through the 18th century.[95] Today only fragments survive, in documents and stone stele markers. The schools also served to maintain alliances and open aboriginal areas for Dutch enterprise and commerce.

The Dutch soon found trade in deerskins and venison in the East Asian market to be a lucrative endeavor[96] and recruited Plains Aborigines to procure the hides. The deer trade attracted the first Han traders to aboriginal villages, but as early as 1642 the demand for deer greatly diminished the deer stocks. This drop significantly reduced the prosperity of aboriginal peoples,[97] forcing many aborigines to take up farming to counter the economic impact of losing their most vital food source.

.jpg.webp)

As the Dutch began subjugating aboriginal villages in the south and west of Taiwan, increasing numbers of Han immigrants looked to exploit areas that were fertile and rich in game. The Dutch initially encouraged this, since the Han were skilled in agriculture and large-scale hunting. Several Han took up residence in Siraya villages. The Dutch used Han agents to collect taxes, hunting license fees and other income. This set up a society in which "many of the colonists were Han Chinese but the military and the administrative structures were Dutch".[98] Despite this, local alliances transcended ethnicity during the Dutch period. For example, the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652, a Han farmers' uprising, was defeated by an alliance of 120 Dutch musketeers with the aid of Han loyalists and 600 aboriginal warriors.[99]

Multiple Aboriginal villages in frontier areas rebelled against the Dutch in the 1650s due to oppression such as when the Dutch ordered aboriginal women for sex, deer pelts, and rice be given to them from aborigines in the Taipei Basin in Wu-lao-wan village which sparked a rebellion in December 1652 at the same time as the Chinese rebellion. Two Dutch translators were beheaded by the Wu-lao-wan aborigines and in a subsequent fight, 30 aboriginals and another two Dutch people died. After an embargo of salt and iron on Wu-lao-wan, the aboriginals were forced to sue for peace in February 1653.[100]

However, the Taiwanese Aboriginal peoples who were previously allied with the Dutch against the Chinese during the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652 turned against the Dutch during the later Siege of Fort Zeelandia and defected to Koxinga's Chinese forces.[101] The Aboriginals (Formosans) of Sincan defected to Koxinga after he offered them amnesty; the Sincan Aboriginals then proceeded to work for the Chinese and behead Dutch people in executions while the frontier aboriginals in the mountains and plains also surrendered and defected to the Chinese on 17 May 1661, celebrating their freedom from compulsory education under the Dutch rule by hunting down Dutch people and beheading them and trashing their Christian school textbooks.[102] Koxinga formulated a plan to give oxen and farming tools and teach farming techniques to the Taiwan Aboriginals, giving them Ming gowns and caps, eating with their chiefs and gifting tobacco to Aboriginals who were gathered in crowds to meet and welcome him as he visited their villages after he defeated the Dutch.[103]

The Dutch period ended in 1662 when Ming loyalist forces of Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga) drove out the Dutch and established the short-lived Zheng family kingdom on Taiwan. The Zhengs brought 70,000 soldiers to Taiwan and immediately began clearing large tracts of land to support its forces. Despite the preoccupation with fighting the Qing, the Zheng family was concerned with aboriginal welfare on Taiwan. The Zhengs built alliances, collected taxes and erected aboriginal schools, where Taiwan's aborigines were first introduced to the Confucian Classics and Chinese writing.[104] However, the impact of the Dutch was deeply ingrained in aboriginal society. In the 19th and 20th centuries, European explorers wrote of being welcomed as kin by the aborigines who thought they were the Dutch, who had promised to return.[105]

Qing Dynasty rule (1683–1895)

After the Qing Dynasty government defeated the Ming loyalist forces maintained by the Zheng family in 1683, Taiwan became increasingly integrated into the Qing Dynasty.[106] Qing forces ruled areas of Taiwan's highly populated western plain for over two centuries, until 1895. This era was characterized by a marked increase in the number of Han Chinese on Taiwan, continued social unrest, the piecemeal transfer (by various means) of large amounts of land from the aborigines to the Han, and the nearly complete acculturation of the Western Plains Aborigines to Chinese Han customs.

During the Qing Dynasty's two-century rule over Taiwan, the population of Han on the island increased dramatically. However, it is not clear to what extent this was due to an influx of Han settlers, who were predominantly displaced young men from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in Fujian province,[107] or from a variety of other factors, including: frequent intermarriage between Han and aborigines, the replacement of aboriginal marriage and abortion taboos, and the widespread adoption of the Han agricultural lifestyle due to the depletion of traditional game stocks, which may have led to increased birth rates and population growth. Moreover, the acculturation of aborigines in increased numbers may have intensified the perception of a swell in the number of Han.

The Qing government officially sanctioned controlled Han settlement, but sought to manage tensions between the various regional and ethnic groups. Therefore, it often recognized the Plains peoples' claims to deer fields and traditional territory.[108][109] The Qing authorities hoped to turn the Plains peoples into loyal subjects, and adopted the head and corvée taxes on the aborigines, which made the Plains Aborigines directly responsible for payment to the government yamen. The attention paid by the Qing authorities to aboriginal land rights was part of a larger administrative goal to maintain a level of peace on the turbulent Taiwan frontier, which was often marred by ethnic and regional conflict.[110] The frequency of rebellions, riots, and civil strife in Qing Dynasty Taiwan is often encapsulated in the saying "every three years an uprising; every five years a rebellion".[111] Aboriginal participation in a number of major revolts during the Qing era, including the Taokas-led Ta-Chia-hsi revolt of 1731–1732, ensured the Plains peoples would remain an important factor in crafting Qing frontier policy until the end of Qing rule in 1895.[112]

The struggle over land resources was one source of conflict. Large areas of the western plain were subject to large land rents called Huan Da Zu (番大租—literally, "Barbarian Big Rent"), a category which remained until the period of Japanese colonization. The large tracts of deer field, guaranteed by the Qing, were owned by the communities and their individual members. The communities would commonly offer Han farmers a permanent patent for use, while maintaining ownership (skeleton) of the subsoil (田骨), which was called "two lords to a field" (一田兩主). The Plains peoples were often cheated out of land or pressured to sell at unfavorable rates. Some disaffected subgroups moved to central or eastern Taiwan, but most remained in their ancestral locations and acculturated or assimilated into Han society.[113]

Migration to highlands

One popular narrative holds that all of the Gaoshan peoples were originally Plains peoples, which fled to the mountains under pressure from Han encroachment. This strong version of the "migration" theory has been largely discounted by contemporary research as the Gaoshan people demonstrate a physiology, material cultures and customs that have been adapted for life at higher elevations. Linguistic, archaeological, and recorded anecdotal evidence also suggests there has been island-wide migration of indigenous peoples for over 3,000 years.[114]

Small sub-groups of Plains Aborigines may have occasionally fled to the mountains, foothills or eastern plain to escape hostile groups of Han or other aborigines.[115][116] The "displacement scenario" is more likely rooted in the older customs of many Plains groups to withdraw into the foothills during headhunting season or when threatened by a neighboring village, as observed by the Dutch during their punitive campaign of Mattou in 1636 when the bulk of the village retreated to Tevorangh.[117][118][119] The "displacement scenario" may also stem from the inland migrations of Plains Aborigine subgroups, who were displaced by either Han or other Plains Aborigines and chose to move to the Iilan plain in 1804, the Puli basin in 1823 and another Puli migration in 1875. Each migration consisted of a number of families and totaled hundreds of people, not entire communities.[120][121] There are also recorded oral histories that recall some Plains Aborigines were sometimes captured and killed by Highlands peoples while relocating through the mountains.[122] However, as Shepherd (1993) explained in detail, documented evidence shows that the majority of Plains people remained on the plains, intermarried Hakka and Hoklo immigrants from Fujian and Guangdong, and adopted a Han identity.

Highland peoples

Imperial Chinese and European societies had little contact with the Highland aborigines until expeditions to the region by European and American explorers and missionaries commenced in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[123][124] The lack of data before this was primarily the result of a Qing quarantine on the region to the east of the "earth oxen" (土牛) border, which ran along the eastern edge of the western plain. Han contact with the mountain peoples was usually associated with the enterprise of gathering and extracting camphor from Camphor Laurel trees (Cinnamomum camphora), native to the island and in particular the mountainous areas. The production and shipment of camphor (used in herbal medicines and mothballs) was then a significant industry on the island, lasting up to and including the period of Japanese rule.[125] These early encounters often involved headhunting parties from the Highland peoples, who sought out and raided unprotected Han forest workers. Together with traditional Han concepts of Taiwanese behavior, these raiding incidents helped to promote the Qing-era popular image of the "violent" aborigine.[126]

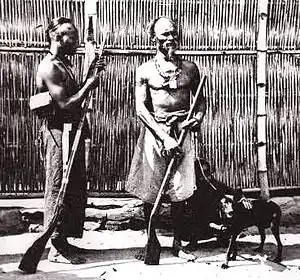

Taiwanese Plains Aborigines were often employed and dispatched as interpreters to assist in the trade of goods between Han merchants and Highlands aborigines. The aborigines traded cloth, pelts and meat for iron and matchlock rifles. Iron was a necessary material for the fabrication of hunting knives—long, curved sabers that were generally used as a forest tool. These blades became notorious among Han settlers, given their alternative use to decapitate Highland indigenous enemies in customary headhunting expeditions.

Headhunting

Every tribe except the Yami of Orchid Island (Tao) practiced headhunting, which was a symbol of bravery and valor.[127] Men who did not take heads could not cross the rainbow bridge into the spirit world upon death as per the religion of Gaya. Each tribe has its own origin story for the tradition of headhunting but the theme is similar across tribes. After the great flood, headhunting originated due to boredom (South Tsou Sa'arua, Paiwan), to improve tribal singing (Ali Mountain Tsou), as a form of population control (Atayal, Taroko, Bunun), simply for amusement and fun (Rukai, Tsou, Puyuma) or particularly for the fun and excitement of killing mentally retarded individuals (Amis). Once the victims had been decapitaded and displayed the heads were boiled and left to dry, often hanging from trees or displayed on slate shelves referred to as "skull racks". A party returning with a head was cause for celebration, as it was believed to bring good luck and the spritual power of the slaughtered individual was believed to transfer into the headhunter. If the head was that of a woman it was even better because it meant she could not bear children. The Bunun people would often take prisoners and inscribe prayers or messages to their dead on arrows, then shoot their prisoner with the hope their prayers would be carried to the dead. Taiwanese Hoklo Han settlers and Japanese were often the victims of headhunting raids as they were considered by the aborigines to be liars and enemies. A headhunting raid would often strike at workers in the fields, or set a dwelling alight and then decapitate the inhabitants as they fled the burning structure. It was also customary to later raise the victim's surviving children as full members of the community. Often the heads themselves were ceremonially 'invited' to join the community as members, where they were supposed to watch over the community and keep them safe. The indigenous inhabitants of Taiwan accepted the convention and practice of headhunting as one of the calculated risks of community life. The last groups to practice headhunting were the Paiwan, Bunun, and Atayal groups.[128] Japanese rule ended the practice by 1930, (though Japanese were not subject to this regulation and continued to headhunt their enemies throughout world war II) but some elder Taiwanese could recall firsthand the practice as late as 2003.[129]

Japanese rule (1895–1945)

When the Treaty of Shimonoseki was finalized on 17 April 1895, Taiwan was ceded by the Qing Empire to Japan.[130] Taiwan's incorporation into the Japanese political orbit brought Taiwanese aborigines into contact with a new colonial structure, determined to define and locate indigenous people within the framework of a new, multi-ethnic empire.[131] The means of accomplishing this goal took three main forms: anthropological study of the natives of Taiwan, attempts to reshape the aborigines in the mould of the Japanese, and military suppression. The Aboriginals and Han joined together to violently revolt against Japanese rule in the 1907 Beipu Uprising and 1915 Tapani Incident.

Japan's sentiment regarding indigenous peoples was crafted around the memory of the Mudan Incident, when, in 1871, a group of 54 shipwrecked Ryūkyūan sailors was massacred by a Paiwan group from the village of Mudan in southern Taiwan. The resulting Japanese policy, published twenty years before the onset of their rule on Taiwan, cast Taiwanese aborigines as "vicious, violent and cruel" and concluded "this is a pitfall of the world; we must get rid of them all".[132] Japanese campaigns to gain aboriginal submission were often brutal, as evidenced in the desire of Japan's first Governor General, Kabayama Sukenori, to "...conquer the barbarians" (Kleeman 2003:20). The Seediq Aboriginals fought against the Japanese in multiple battles such as the Xincheng incident (新城事件), Truku battle (太魯閣之役) (Taroko),[133] 1902 Renzhiguan incident (人止關事件), and the 1903 Zimeiyuan incident 姊妹原事件. In the Musha Incident of 1930, for example, a Seediq group was decimated by artillery and supplanted by the Taroko (Truku), which had sustained periods of bombardment from naval ships and airplanes dropping mustard gas. A quarantine was placed around the mountain areas enforced by armed guard stations and electrified fences until the most remote high mountain villages could be relocated closer to administrative control.[134]

A divide and rule policy was formulated with Japan trying to play Aboriginals and Han against each other to their own benefit when Japan alternated between fighting the two with Japan first fighting Han and then fighting Aboriginals.[135] Nationalist Japanese claim Aboriginals were treated well by Kabayama.[136] unenlightened and stubbornly stupid were the words used to describe Aboriginals by Kabayama Sukenori.[137] A hardline anti Aboriginal position aimed at the destruction of their civilization was implemented by Fukuzawa Yukichi.[138] The most tenacioius opposition was mounted by the Bunan and Atayal against the Japanese during the brutal mountain war in 1913–14 under Sakuma. Aboriginals continued to fight against the Japanese after 1915.[139] Aboriginals were subjected to military takeover and assimilation.[140] In order to exploit camphor resources, the Japanese fought against the Bngciq Atayal in 1906 and expelled them.[141][142] The war is called "Camphor War" (樟腦戰爭).[143][144]

The Bunun Aboriginals under Chief Raho Ari (or Dahu Ali, 拉荷·阿雷, lāhè āléi) engaged in guerilla warfare against the Japanese for twenty years. Raho Ari's revolt was sparked when the Japanese implemented a gun control policy in 1914 against the Aboriginals in which their rifles were impounded in police stations when hunting expeditions were over. The Dafen incident w:zh:大分事件 began at Dafen when a police platoon was slaughtered by Raho Ari's clan in 1915. A settlement holding 266 people called Tamaho was created by Raho Ari and his followers near the source of the Laonong River and attracted more Bunun rebels to their cause. Raho Ari and his followers captured bullets and guns and slew Japanese in repeated hit and run raids against Japanese police stations by infiltrating over the Japanese "guardline" of electrified fences and police stations as they pleased.[145]

The 1930 "New Flora and Silva, Volume 2" said of the mountain Aboriginals that the "majority of them live in a state of war against Japanese authority".[146] The Bunun and Atayal were described as the "most ferocious" Aboriginals, and police stations were targeted by Aboriginals in intermittent assaults.[147] By January 1915, all Aboriginals in northern Taiwan were forced to hand over their guns to the Japanese, however head hunting and assaults on police stations by Aboriginals still continued after that year.[147][148] Between 1921 and 1929 Aboriginal raids died down, but a major revival and surge in Aboriginal armed resistance erupted from 1930–1933 for four years during which the Musha Incident occurred and Bunun carried out raids, after which armed conflict again died down.[149] According to a 1933-year book, wounded people in the Japanese war against the Aboriginals numbered around 4,160, with 4,422 civilians dead and 2,660 military personnel killed.[150] According to a 1935 report, 7,081 Japanese were killed in the armed struggle from 1896–1933 while the Japanese confiscated 29,772 Aboriginal guns by 1933.[151]

Beginning in the first year of Japanese rule, the colonial government embarked on a mission to study the aborigines so they could be classified, located and "civilized". The Japanese "civilizing project", partially fueled by public demand in Japan to know more about the empire, would be used to benefit the Imperial government by consolidating administrative control over the entire island, opening up vast tracts of land for exploitation.[152] To satisfy these needs, "the Japanese portrayed and catalogued Taiwan's indigenous peoples in a welter of statistical tables, magazine and newspaper articles, photograph albums for popular consumption".[153] The Japanese based much of their information and terminology on prior Qing era narratives concerning degrees of "civilization".[154]

Japanese ethnographer Ino Kanori was charged with the task of surveying the entire population of Taiwanese aborigines, applying the first systematic study of aborigines on Taiwan. Ino's research is best known for his formalization of eight peoples of Taiwanese aborigines: Atayal, Bunun, Saisiat, Tsou, Paiwan, Puyuma, Ami and Pepo (Pingpu).[155][156] This is the direct antecedent of the taxonomy used today to distinguish people groups that are officially recognized by the government.

Life under the Japanese changed rapidly as many of the traditional structures were replaced by a military power. Aborigines who wished to improve their status looked to education rather than headhunting as the new form of power. Those who learned to work with the Japanese and follow their customs would be better suited to lead villages. The Japanese encouraged aborigines to maintain traditional costumes and selected customs that were not considered detrimental to society, but invested much time and money in efforts to eliminate traditions deemed unsavory by Japanese culture, including tattooing.[157] By the mid-1930s as Japan's empire was reaching its zenith, the colonial government began a political socialization program designed to enforce Japanese customs, rituals and a loyal Japanese identity upon the aborigines. By the end of World War II, aborigines whose fathers had been killed in pacification campaigns were volunteering to serve in Special Units and if need be die for the Emperor of Japan.[158] The Japanese colonial experience left an indelible mark on many older aborigines who maintained an admiration for the Japanese long after their departure in 1945.[159]

The Japanese troops used Aboriginal women as sex slaves, so called "comfort women".[160]

Kuomintang single-party rule (1945–1987)

Japanese rule of Taiwan ended in 1945, following the armistice with the allies on September 2 and the subsequent appropriation of the island by the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT) on October 25. In 1949, on losing the Chinese Civil War to the Communist Party of China, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek led the Kuomintang in a retreat from Mainland China, withdrawing its government and 1.3 million refugees to Taiwan. The KMT installed an authoritarian form of government and shortly thereafter inaugurated a number of political socialization programs aimed at nationalizing Taiwanese people as citizens of a Chinese nation and eradicating Japanese influence.[161] The KMT pursued highly centralized political and cultural policies rooted in the party's decades-long history of fighting warlordism in China and opposing competing concepts of a loose federation following the demise of the imperial Qing.[52] The project was designed to create a strong national Chinese cultural identity (as defined by the state) at the expense of local cultures.[162] Following the February 28 Incident in 1947, the Kuomintang placed Taiwan under martial law, which was to last for nearly four decades.

Taiwanese aborigines first encountered the Nationalist government in 1946, when the Japanese village schools were replaced by schools of the KMT. Documents from the Education Office show an emphasis on Chinese language, history and citizenship — with a curriculum steeped in pro-KMT ideology. Some elements of the curriculum, such as the Wu Feng Legend, are currently considered offensive to aborigines.[163] Much of the burden of educating the aborigines was undertaken by unqualified teachers, who could, at best, speak Mandarin and teach basic ideology.[164] In 1951 a major political socialization campaign was launched to change the lifestyle of many aborigines, to adopt Han customs. A 1953 government report on mountain areas stated that its aims were chiefly to promote Mandarin to strengthen a national outlook and create good customs. This was included in the Shandi Pingdi Hua (山地平地化) policy to "make the mountains like the plains".[165] Critics of the KMT's program for a centralized national culture regard it as institutionalized ethnic discrimination, point to the loss of several indigenous languages and a perpetuation of shame for being an aborigine. Hsiau noted that Taiwan's first democratically elected President, Li Teng-Hui, said in a famous interview: "... In the period of Japanese colonialism a Taiwanese would be punished by being forced to kneel out in the sun for speaking Tai-yü." [a dialect of Min Nan, which is not a Formosan language].[166]

The pattern of intermarriage continued, as many KMT soldiers married aboriginal women who were from poorer areas and could be easily bought as wives.[165] Modern studies show a high degree of genetic intermixing. Despite this, many contemporary Taiwanese are unwilling to entertain the idea of having an aboriginal heritage. In a 1994 study, it was found that 71% of the families surveyed would object to their daughter marrying an aboriginal man. For much of the KMT era the government definition of aboriginal identity had been 100% aboriginal parentage, leaving any intermarriage resulting in a non-aboriginal child. Later the policy was adjusted to the ethnic status of the father determining the status of the child.[167]

Transition to democracy

Authoritarian rule under the Kuomintang ended gradually through a transition to democracy, which was marked by the lifting of martial law in 1987. Soon after, the KMT transitioned to being merely one party within a democratic system, though maintaining a high degree of power in aboriginal districts through an established system of patronage networks.[168] The KMT continued to hold the reins of power for another decade under President Lee Teng-hui. However, they did so as an elected government rather than a dictatorial power. The elected KMT government supported many of the bills that had been promoted by aboriginal groups. The tenth amendment to the Constitution of the Republic of China also stipulates that the government would protect and preserve aboriginal culture and languages and also encourage them to participate in politics.

During the period of political liberalization, which preceded the end of martial law, academic interest in the Plains Aborigines surged as amateur and professional historians sought to rediscover Taiwan's past. The opposition tang wai activists seized upon the new image of the Plains Aborigines as a means to directly challenge the KMT's official narrative of Taiwan as a historical part of China, and the government's assertion that Taiwanese were "pure" Han Chinese.[169][170] Many tang wai activists framed the Plains aboriginal experience in the existing anti-colonialism/victimization Taiwanese nationalist narrative, which positioned the Hoklo-speaking Taiwanese in the role of indigenous people and the victims of successive foreign rulers.[171][172][173] By the late 1980s many Hoklo- and Hakka-speaking people began identifying themselves as Plains Aborigines, though any initial shift in ethnic consciousness from Hakka or Hoklo people was minor. Despite the politicized dramatization of the Plains Aborigines, their "rediscovery" as a matter of public discourse has had a lasting effect on the increased socio-political reconceptualization of Taiwan—emerging from a Han Chinese-dominant perspective into a wider acceptance of Taiwan as a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic community.[174]

In many districts Taiwanese aborigines tend to vote for the Kuomintang, to the point that the legislative seats allocated to the aborigines are popularly described as iron votes for the pan-blue coalition. This may seem surprising in light of the focus of the pan-green coalition on promoting aboriginal culture as part of the Taiwanese nationalist discourse against the KMT. However, this voting pattern can be explained on economic grounds, and as part of an inter-ethnic power struggle waged in the electorate. Some aborigines see the rhetoric of Taiwan nationalism as favoring the majority Hoklo speakers rather than themselves. Aboriginal areas also tend to be poor and their economic vitality tied to the entrenched patronage networks established by the Kuomintang over the course of its fifty-five year reign.[175][176][177]

Aborigines in the democratic era

The democratic era has been a time of great change, both constructive and destructive, for the aborigines of Taiwan. Since the 1980s, increased political and public attention has been paid to the rights and social issues of the indigenous communities of Taiwan. Aborigines have realized gains in both the political and economic spheres. Though progress is ongoing, there remain a number of still unrealized goals within the framework of the ROC: "although certainly more 'equal' than they were 20, or even 10, years ago, the indigenous inhabitants in Taiwan still remain on the lowest rungs of the legal and socioeconomic ladders".[35] On the other hand, bright spots are not hard to find. A resurgence in ethnic pride has accompanied the aboriginal cultural renaissance, which is exemplified by the increased popularity of aboriginal music and greater public interest in aboriginal culture.[178]

Aboriginal political movement

The movement for indigenous cultural and political resurgence in Taiwan traces its roots to the ideals outlined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).[179] Although the Republic of China was a UN member and signatory to the original UN Charter, four decades of martial law controlled the discourse of culture and politics on Taiwan. The political liberalization Taiwan experienced leading up to the official end of martial law on 15 July 1987, opened a new public arena for dissenting voices and political movements against the centralized policy of the KMT.

In December 1984, the Taiwan Aboriginal People's Movement was launched when a group of aboriginal political activists, aided by the progressive Presbyterian Church in Taiwan (PCT),[180] established the Alliance of Taiwan Aborigines (ATA, or yuan chuan hui) to highlight the problems experienced by indigenous communities all over Taiwan, including: prostitution, economic disparity, land rights and official discrimination in the form of naming rights.[181][182][59]

In 1988, amid the ATA's Return Our Land Movement, in which aborigines demanded the return of lands to the original inhabitants, the ATA sent its first representative to the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations.[183] Following the success in addressing the UN, the "Return Our Land" movement evolved into the Aboriginal Constitution Movement, in which the aboriginal representatives demanded appropriate wording in the ROC Constitution to ensure indigenous Taiwanese "dignity and justice" in the form of enhanced legal protection, government assistance to improve living standards in indigenous communities, and the right to identify themselves as "yuan chu min" (原住民), literally, "the people who lived here first," but more commonly, "aborigines".[184] The KMT government initially opposed the term, due to its implication that other people on Taiwan, including the KMT government, were newcomers and not entitled to the island. The KMT preferred hsien chu min (先住民, "First people"), or tsao chu min (早住民, "Early People") to evoke a sense of general historical immigration to Taiwan.[185]

To some degree the movement has been successful. Beginning in 1998, the official curriculum in Taiwan schools has been changed to contain more frequent and favorable mention of aborigines. In 1996 the Council of Indigenous Peoples was promoted to a ministry-level rank within the Executive Yuan. The central government has taken steps to allow romanized spellings of aboriginal names on official documents, offsetting the long-held policy of forcing a Han name on an aborigine. A relaxed policy on identification now allows a child to choose their official designation if they are born to mixed aboriginal/Han parents.

The present political leaders in the aboriginal community, led mostly by aboriginal elites born after 1949, have been effective in leveraging their ethnic identity and socio-linguistic acculturation into contemporary Taiwanese society against the political backdrop of a changing Taiwan.[186] This has allowed indigenous people a means to push for greater political space, including the still unrealized prospect of Indigenous People's Autonomous Areas within Taiwan.[187][35][42]

In February 2017, the Indigenous Ketagalan Boulevard Protest started in a bid for more official recognition of land as traditional territories.

Aboriginal political representation

Aborigines were represented by eight members out of 225 seats in the Legislative Yuan. In 2008, the number of legislative seats was cut in half to 113, of which Taiwanese aborigines are represented by six members, three each for lowland and highland peoples.[188] The tendency of Taiwanese aborigines to vote for members of the pan-blue coalition has been cited as having the potential to change the balance of the legislature. Citing these six seats in addition with five seats from smaller counties that also tend to vote pan-blue has been seen as giving the pan-blue coalition 11 seats before the first vote is counted.[176]

The deep-rooted hostility between Aboriginals and (Taiwanese) Hoklo, and the Aboriginal communities’ effective KMT networks, contribute to Aboriginal skepticism against the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the Aboriginals tendency to vote for the KMT.[189]

Aboriginals have criticized politicians for abusing the "indigenization" movement for political gains, such as aboriginal opposition to the DPP's "rectification" by recognizing the Taroko for political reasons, with the majority of mountain townships voting for Ma Ying-jeou.[190] The Atayal and Seediq slammed the Truku for their name rectification.[191]

In 2005 the Kuomintang displayed a massive photo of the anti-Japanese Aboriginal leader Mona Rudao at its headquarters in honor of the 60th anniversary of Taiwan's handover from Japan to the Republic of China.[192]

Kao Chin Su-mei led Aboriginal legislators to protest against the Japanese at Yasukuni shrine.[193][194][195][196]

Aboriginals protested against the 14th Dalai Lama during his visit to Taiwan after Typhoon Morakot and denounced it as politically motivated.[197][198][199][200]

The derogatory term "fan" (Chinese: 番) was often used against the Plains Aborigines by the Taiwanese. The Hoklo Taiwanese term was forced upon Aborigines like the Pazeh.[201] A racist, anti-Aboriginal slur was also used by Chiu Yi-ying, a DPP Taiwanese legislator.[202] Chiu Yi-ying said the racist words were intended for Aboriginal KMT members.[203] The Aborigines in the KMT slammed President Tsai over the criminal punishment of a hunter of Bunun Aboriginal background.[204] In response to the "apology" ceremony held by Tsai, KMT Aboriginals refused to attend.[205] Aboriginals demanded that recompense from Tsai to accompany the apology.[206] Aboriginal protestors slammed Tsai for not implementing sovereignty for Aboriginals and not using actions to back up the apology.[207] The Taipei Times ran an editorial in 2008 that rejected the idea of an apology to the Aborigines, and rejected the idea of comparing Australian Aborigines' centuries of 'genocidal' suffering by White Australians to the suffering of Aborigines in Taiwan.[208]

Inter-ethnic conflicts

During the Wushe Incident Seediq Tkdaya under Mona Rudao revolted against the Japanese while the Truku and Toda did not. The rivalry between the Seediq Tkdaya vs the Toda and Truku (Taroko) was aggravated by the Wushe Incident, since the Japanese had long played them off against each other and the Japanese used Toda and Truku (Taroko) collaborators to massacre the Tkdaya. Tkdaya land was given to the Truku (Taroko) and Toda by the Japanese after the incident. The Truku had resisted and fought the Japanese before in the 1914 Truku war 太魯閣戰爭 but had since been pacified and collaborated with the Japanese in the 1930 Wushe against the Tkdaya.

Economic issues

Many indigenous communities did not evenly share in the benefits of the economic boom Taiwan experienced during the last quarter of the 20th century. They often lacked satisfactory educational resources on their reservations, undermining their pursuit of marketable skills. The economic disparity between the village and urban schools resulted in imposing many social barriers on aborigines, which prevent many from moving beyond vocational training. Students transplanted into urban schools face adversity, including isolation, culture shock, and discrimination from their peers.[209] The cultural impact of poverty and economic marginalization has led to an increase in alcoholism and prostitution among aborigines.[210][11]

The economic boom resulted in drawing large numbers of aborigines out of their villages and into the unskilled or low-skilled sector of the urban workforce.[211] Manufacturing and construction jobs were generally available for low wages. The aborigines quickly formed bonds with other communities as they all had similar political motives to protect their collective needs as part of the labor force. The aborigines became the most skilled iron-workers and construction teams on the island often selected to work on the most difficult projects. The result was a mass exodus of indigenous members from their traditional lands and the cultural alienation of young people in the villages, who could not learn their languages or customs while employed. Often, young aborigines in the cities fall into gangs aligned with the construction trade. Recent laws governing the employment of laborers from Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines have also led to an increased atmosphere of xenophobia among urban aborigines, and encouraged the formulation of a pan-indigenous consciousness in the pursuit of political representation and protection.[212]

| Date | Total population | Age 15 and above | Total work force | Employed | Unemployed | Labor participation rate (%) | Unemployment rate (%) |

| December 2005 | 464,961 | 337,351 | 216,756 | 207,493 | 9,263 | 64.25 | 4.27 |

| Dec. 2006 | 474,919 | 346,366 | 223,288 | 213,548 | 9,740 | 64.47 | 4.36 |

| Dec. 2007 | 484,174 | 355,613 | 222,929 | 212,627 | 10,302 | 62.69 | 4.62 |

| Dec. 2008 | 494,107 | 363,103 | 223,464 | 205,765 | 17,699 | 61.54 | 7.92 |

| Dec. 2009 | 504,531 | 372,777 | 219,465 | 203,412 | 16,053 | 58.87 | 7.31 |

Religion

Of the current population of Taiwanese aborigines, about 70% identify themselves as Christian. Moreover, many of the Plains groups have mobilized their members around predominantly Christian organizations; most notably the Taiwan Presbyterian Church and Catholicism.[213]

Before contact with Christian missionaries during both the Dutch and Qing periods, Taiwanese aborigines held a variety of beliefs in spirits, gods, sacred symbols and myths that helped their societies find meaning and order. Although there is no evidence of a unified belief system shared among the various indigenous groups, there is evidence that several groups held supernatural beliefs in certain birds and bird behavior. The Siraya were reported by Dutch sources to incorporate bird imagery into their material culture. Other reports describe animal skulls and the use of human heads in societal beliefs. The Paiwan and other southern groups worship the Formosan hundred pacer snake and use the diamond patterns on its back in many designs.[214] In many Plains Aborigines societies, the power to communicate with the supernatural world was exclusively held by women called Inibs. During the period of Dutch colonization, the Inibs were removed from the villages to eliminate their influence and pave the way for Dutch missionary work.[215]

During the Zheng and Qing eras, Han immigrants brought Confucianized beliefs of Taoism and Buddhism to Taiwan's indigenous people. Many Plains Aborigines adopted Han religious practices, though there is evidence that many aboriginal customs were transformed into local Taiwanese Han beliefs. In some parts of Taiwan the Siraya spirit of fertility, Ali-zu (A-li-tsu) has become assimilated into the Han pantheon.[216] The use of female spirit mediums (tongji) can also be traced to the earlier matrilineal Inibs.

Although many aborigines assumed Han religious practices, several sub-groups sought protection from the European missionaries, who had started arriving in the 1860s. Many of the early Christian converts were displaced groups of Plains Aborigines that sought protection from the oppressive Han. The missionaries, under the articles of extraterritoriality, offered a form of power against the Qing establishment and could thus make demands on the government to provide redress for the complaints of Plains Aborigines.[217] Many of these early congregations have served to maintain aboriginal identity, language and cultures.

The influence of 19th- and 20th-century missionaries has both transformed and maintained aboriginal integration. Many of the churches have replaced earlier community functions, but continue to retain a sense of continuity and community that unites members of aboriginal societies against the pressures of modernity. Several church leaders have emerged from within the communities to take on leadership positions in petitioning the government in the interest of indigenous peoples[218] and seeking a balance between the interests of the communities and economic vitality.

Ecological issues

The indigenous communities of Taiwan are closely linked with ecological awareness and conservation issues on the island, as many of the environmental issues are spearheaded by aborigines. Political activism and sizable public protests regarding the logging of the Chilan Formosan Cypress, as well as efforts by an Atayal member of the Legislative Yuan, "focused debate on natural resource management and specifically on the involvement of aboriginal people therein".[219] Another high-profile case is the nuclear waste storage facility on Orchid Island, a small tropical island 60 km (37 mi; 32 nmi) off the southeast coast of Taiwan. The inhabitants are the 4,000 members of the Tao (or Yami). In the 1970s the island was designated as a possible site to store low and medium grade nuclear waste. The island was selected on the grounds that it would be cheaper to build the necessary infrastructure for storage and it was thought that the population would not cause trouble.[220] Large-scale construction began in 1978 on a site 100 m (330 ft) from the Immorod fishing fields. The Tao alleges that government sources at the time described the site as a "factory" or a "fish cannery", intended to bring "jobs [to the] home of the Tao/Yami, one of the least economically integrated areas in Taiwan".[35] When the facility was completed in 1982, however, it was in fact a storage facility for "97,000 barrels of low-radiation nuclear waste from Taiwan's three nuclear power plants".[221] The Tao have since stood at the forefront of the anti-nuclear movement and launched several exorcisms and protests to remove the waste they claim has resulted in deaths and sickness.[222] The lease on the land has expired, and an alternative site has yet to be selected.[223] The competition between different ways of representing and interpreting indigenous culture among local tourism operators does exist and creates tensions between indigenous tour guides and the NGOs which help to design and promote ethno/ecotourism. E.g., in a Sioulin Township, the government sponsored a project “Follow the Footsteps of Indigenous Hunters”. Academics and members from environmental NGOs have suggested a new way of hunting: to replace shotgun with camera. Hunters benefit from the satisfaction of ecotourists who may spot wild animals under the instructions of accompanied indigenous hunters [Chen, 2012]. The rarer the animals are witnessed by tourists, the higher the pay will be to the hunters.[224]

Parks, tourism, and commercialization

Aboriginal groups are seeking to preserve their folkways and languages as well as to return to, or remain on, their traditional lands. Eco-tourism, sewing and selling carvings, jewelry and music have become viable areas of economic opportunity. However, tourism-based commercial development, such as the creation of Taiwan Aboriginal Culture Park, is not a panacea. Although these create new jobs, aborigines are seldom given management positions. Moreover, some national parks have been built on aboriginal lands against the wishes of the local communities, prompting one Taroko activist to label the Taroko National Park as a form of "environmental colonialism".[157] At times, the creation of national parks has resulted in forced resettlement of the aborigines.[225]

Due to the close proximity of aboriginal land to the mountains, many communities have hoped to cash in on hot spring ventures and hotels, where they offer singing and dancing to add to the ambience. The Wulai Atayal in particular have been active in this area. Considerable government funding has been allocated to museums and culture centers focusing on Taiwan's aboriginal heritage. Critics often call the ventures exploitative and "superficial portrayals" of aboriginal culture, which distract attention from the real problems of substandard education.[226] Proponents of ethno-tourism suggest that such projects can positively impact the public image and economic prospects of the indigenous community.

The attractive tourist destination includes natural resources, infrastructure, customs and culture, as well as the characteristics of the local industry. Thus, the role of the local community in influencing the tourism development activities is clear. The essence of tourism in today's world is the development and delivery of travel and visitation experiences to a range of individuals and groups who wish to see, understand, and experience the nature of different destinations and the way people live, work, and enjoy life in those destinations. The attitude of local people towards tourists constitutes one of the elements of a destination's tourism value chain.[224] The attraction is a tourist area's experience theme, however the main appeal is the formation of the fundamentals of the tourism image in the region [Kao, 1995]. Attraction sources can be diverse, including the area's natural resources, economic activities, customs, development history, religion, outdoor recreation activities, events and other related resources. This way, the awareness of indigenous resources constitutes an attraction to tourists. The aboriginal culture is an important indicator of tourism products’ attractiveness and a new type of economic sources.[224]

While there is an important need to link the economic, cultural, and ecological imperatives of development in the context of tourism enterprises, there is the key question of implementation and how the idea of sustainable tourism enterprises can be translated into reality: formulation of strategies and how they may be expected to interact with important aspects of indigenous culture. In addition to being locally directed and relevant, the planning process for the establishment of an ethno/ecotourism enterprise in an indigenous community should be strategic in nature. The use of a strategic planning process enables indigenous culture to be regarded as an important characteristic requiring careful consideration, rather than a feature to be exploited, or an incidental characteristic that is overshadowed by the natural features of the environment.[224]

Music