Tanker (ship)

A tanker (or tank ship or tankship) is a ship designed to transport or store liquids or gases in bulk. Major types of tankship include the oil tanker, the chemical tanker, and gas carrier. Tankers also carry commodities such as vegetable oils, molasses and wine. In the United States Navy and Military Sealift Command, a tanker used to refuel other ships is called an oiler (or replenishment oiler if it can also supply dry stores) but many other navies use the terms tanker and replenishment tanker.

Description

Tankers can range in size of capacity from several hundred tons, which includes vessels for servicing small harbours and coastal settlements, to several hundred thousand tons, for long-range haulage. Besides ocean- or seagoing tankers there are also specialized inland-waterway tankers which operate on rivers and canals with an average cargo capacity up to some thousand tons. A wide range of products are carried by tankers, including:

- Hydrocarbon products such as oil, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and liquefied natural gas (LNG)

- Chemicals, such as ammonia, chlorine, and styrene monomer

- Fresh water

- Wine

- Molasses

- Citrus juice

Tankers are a relatively new concept, dating from the later years of the 19th century. Before this, technology had simply not supported the idea of carrying bulk liquids. The market was also not geared towards transporting or selling cargo in bulk, therefore most ships carried a wide range of different products in different holds and traded outside fixed routes. Liquids were usually loaded in casks—hence the term "tonnage", which refers to the volume of the holds in terms of how many tuns or casks of wine could be carried. Even potable water, vital for the survival of the crew, was stowed in casks. Carrying bulk liquids in earlier ships posed several problems:

- The holds: on timber ships the holds were not sufficiently water, oil or air-tight to prevent a liquid cargo from spoiling or leaking. The development of iron and steel hulls solved this problem.

- Loading and discharging: Bulk liquids must be pumped - the development of efficient pumps and piping systems was vital to the development of the tanker. Steam engines were developed as prime-movers for early pumping systems. Dedicated cargo handling facilities were now required ashore too - as was a market for receiving a product in that quantity. Casks could be unloaded using ordinary cranes, and the awkward nature of the casks meant that the volume of liquid was always relatively small - therefore keeping the market more stable.

- Free surface effect: a large body of liquid carried aboard a ship will affect the ship's stability, particularly when the liquid is flowing around the hold or tank in response to the ship's movements. The effect was negligible in casks, but could cause capsizing if the tank extended the width of the ship; a problem solved by extensive subdivision of the tanks.

Tankers were first used by the oil industry to transfer refined fuel in bulk from refineries to customers. This would then be stored in large tanks ashore, and subdivided for delivery to individual locations. The use of tankers caught on because other liquids were also cheaper to transport in bulk, store in dedicated terminals, then subdivide. Even the Guinness brewery used tankers to transport the stout across the Irish Sea.

Different products require different handling and transport, with specialised variants such as "chemical tankers", "oil tankers", and "LNG carriers" developed to handle dangerous chemicals, oil and oil-derived products, and liquefied natural gas respectively. These broad variants may be further differentiated with respect to ability to carry only a single product or simultaneously transport mixed cargoes such as several different chemicals or refined petroleum products.[1] Among oil tankers, supertankers are designed for transporting oil around the Horn of Africa from the Middle East. The supertanker Seawise Giant, scrapped in 2010, was 458 meters (1,503 ft) in length and 69 meters (226 ft) wide. Supertankers are one of the three preferred methods for transporting large quantities of oil, along with pipeline transport and rail.

Despite being highly regulated, tankers have been involved in environmental disasters resulting from oil spills. Amoco Cadiz, Braer, Erika, Exxon Valdez, Prestige and Torrey Canyon were examples of coastal accidents.

Primary maritime cargo types

| Primary maritime cargo types | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cargo type | Countable | Packaging | Container | Remarks |

| Break bulk cargo or general cargo | Countable | Yes | No | Break bulk cargo or general cargo are goods that must be loaded individually, and not in intermodal containers nor in bulk as with oil or grain. Ships that carry this sort of cargo are called general cargo ships. The term break bulk derives from the phrase breaking bulk—the extraction of a portion of the cargo of a ship or the beginning of the unloading process from the ship's holds. These goods may not be in shipping containers. Break bulk cargo is transported in bags, boxes, crates, drums, or barrels. Unit loads of items secured to a pallet or skid are also used.[2] |

| Bulk cargo (bulk dry cargo) | Weighable | No | No | Bulk cargo is commodity cargo that is transported unpackaged in large quantities. It refers to material in either liquid or granular, particulate form, as a mass of relatively small solids, such as petroleum/crude oil, grain, coal, or gravel. This cargo is usually dropped or poured, with a spout or shovel bucket, into a bulk carrier ship's hold, railroad car/railway wagon, or tanker truck/trailer/semi-trailer body. Smaller quantities (still considered "bulk") can be boxed (or drummed) and palletised. Bulk cargo is classified as liquid or dry. |

| Bulk liquid cargo | Weighable | No | No | A tanker (or tank ship or tankship) is a ship designed to transport or store liquids or gases in bulk. Major types of tankship include the oil tanker, the chemical tanker, and gas carrier. Tankers also carry commodities such as vegetable oils, molasses and wine. In the United States Navy and Military Sealift Command, a tanker used to refuel other ships is called an oiler (or replenishment oiler if it can also supply dry stores) but many other navies use the terms tanker and replenishment tanker. A wide range of products are carried by tankers, including:

|

| Container cargo | Countable | Yes | Yes | Containerization is a system of intermodal freight transport using intermodal containers (also called shipping containers and ISO containers).[3] The containers have standardized dimensions. They can be loaded and unloaded, stacked, transported efficiently over long distances, and transferred from one mode of transport to another—container ships, rail transport flatcars, and semi-trailer trucks—without being opened. The handling system is completely mechanized so that all handling is done with cranes [4] and special forklift trucks. All containers are numbered and tracked using computerized systems. |

| Neo-bulk cargo | Weighable | Yes | No | In the ocean shipping trade, neo-bulk cargo is a type of cargo that is a subcategory of general cargo, alongside the other subcategories of break-bulk cargo and containerized cargo.[5] (Gerhardt Muller, erstwhile professor at the United States Merchant Marine Academy and Manager of Regional Intermodal Planning of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, promotes it from a subcategory to being a third major category of cargo in its own right, alongside general and bulk cargo.[6][7]) It comprises goods that are prepackaged, counted as they are loaded and unloaded (as opposed to bulk cargo where individual items are not counted), not stored in containers, and transferred as units at port.[5] Types of neo-bulk cargo goods include heavy machinery, lumber, bundled steel, scrap iron, bananas, waste paper, and cars.[5][8][7] The category has only become recognized as a distinct cargo category in its own right in recent decades.[6][7] |

| Passenger cargo | Countable | No | No | A passenger ship is a merchant ship whose primary function is to carry passengers on the sea. |

| Project cargo | Weighable | Yes | No | Project cargo is a term used to broadly describe the national or international transportation of large, heavy, high value, or critical (to the project they are intended for) pieces of equipment. Also commonly referred to as heavy lift, this includes shipments made of various components which need disassembly for shipment and reassembly after delivery. |

| Refrigerated cargo | Weighable | Yes | Yes / no | A reefer ship is a refrigerated cargo ship, typically used to transport perishable commodities which require temperature-controlled transportation, such as fruit, meat, fish, vegetables, dairy products and other foods. |

| Roll-on/roll-off cargo | Countable | No | No | Roll-on/roll-off (RORO or ro-ro) ships are vessels designed to carry wheeled cargo, such as cars, trucks, semi-trailer trucks, trailers, and railroad cars, that are driven on and off the ship on their own wheels or using a platform vehicle, such as a self-propelled modular transporter. This is in contrast to lift-on/lift-off (LOLO) vessels, which use a crane to load and unload cargo. |

Design considerations

Many modern tankers are designed for a specific cargo and a specific route. Draft is typically limited by the depth of water in loading and unloading harbors; and may be limited by the depth of straits along the preferred shipping route. Cargoes with high vapor pressure at ambient temperatures may require pressurized tanks or vapor recovery systems. Tank heaters may be required to maintain heavy crude oil, residual fuel, asphalt, wax, or molasses in a fluid state for offloading.[9]

Tanker capacity

Tankers used for liquid fuels are classified according to their capacity.

In 1954, Shell Oil developed the average freight rate assessment (AFRA) system, which classifies tankers of different sizes. To make it an independent instrument, Shell consulted the London Tanker Brokers’ Panel (LTBP). At first, they divided the groups as General Purpose for tankers under 25,000 tons deadweight (DWT); Medium Range for ships between 25,000 and 45,000 DWT and Large Range for the then-enormous ships that were larger than 45,000 DWT. The ships became larger during the 1970s, and the list was extended, where the tons are long tons:[10]

- 10,000–24,999 DWT: Small tanker

- 25,000–34,999 DWT: Intermediate tanker

- 35,000–44,999 DWT: Medium Range 1 (MR1)

- 45,000–54,999 DWT: Medium Range 2 (MR2)

- 55,000–79,999 DWT: Large Range 1 (LR1

- 80,000–159,999 DWT: Large Range 2 (LR2)

- 160,000–319,999 DWT: Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC)

- 320,000–549,999 DWT: Ultra Large Crude Carrier (ULCC)

- Very Large Crude Carrier size range

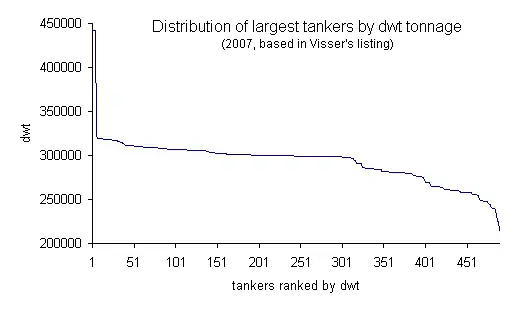

At nearly 380 vessels in the size range 279,000 t DWT to 320,000 t DWT, these are by far the most popular size range among the larger VLCCs. Only seven vessels are larger than this, and approximately 90 between 220,000 t DWT and 279,000 t DWT.[11]

Fleets of the world

- Flag states

As of 2005, the United States Maritime Administration's statistics count 4,024 tankers of 10,000 LT DWT or greater worldwide.[12] 2,582 of these are double-hulled. Panama is the leading flag state of tankers, with 592 registered ships. Five other flag states have more than two hundred registered tankers: Liberia (520), The Marshall Islands (323), Greece (233), Singapore (274) and The Bahamas (215). These flag states are also the top six in terms of fleet size in terms of deadweight tonnage.[12]

- Largest fleets

Greece, Japan, and the United States are the top three owners of tankers (including those owned but registered to other nations), with 733, 394, and 311 vessels respectively. These three nations account for 1,438 vessels or over 36% of the world's fleet.[12]

- Builders

Asian companies dominate the construction of tankers. Of the world's 4,024 tankers, 2,822 (over 70%) were built in South Korea, Japan and China.[12]

Further reading

Petroleum Tables, a book by William Davies, an early tanker captain, was published in 1903, although Davies had printed earlier versions himself.[13] Including his calculations on the expansion and contraction of bulk oil, and other information for tanker officers, it went into multiple editions, and in 1915 The Petroleum World commented that it was "the standard book for computations and conversions."[14]

Notes

- Morrell 1931, p. 1.

- Notes on Cargo Work by J. F. Kemp and Peter Young, 1971 (3rd edition); page 31. ISBN 0-85309-040-8.

- Edmonds, John (2017-03-03). "The Freight Essentials: Getting Your Products Across The Ocean". Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- Lewandowski, Krzysztof (2016). "Growth in the Size of Unit Loads and Shipping Containers from Antique to WWI". Packaging Technology and Science. 29 (8–9): 451–478. doi:10.1002/pts.2231. ISSN 1099-1522.

- CambridgeSystematics 1998, pp. 79.

- Muller 1998, pp. 90.

- Muller 1995, pp. 3.

- Seyoum 2008, pp. 207.

- Morrell 1931, pp. 1; 8.

- Evangelista, Joe, Ed. (Winter 2002). "Scaling the Tanker Market" (PDF). Surveyor. American Bureau of Shipping (4): 5–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- Auke Visser (22 February 2007). "Tanker list, status 01-01-2007". International Super Tankers. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- Office of Data and Economic Analysis (July 2006). "World Merchant Fleet 2001–2005" (PDF). United States Maritime Administration: 3, 5, 6. Archived from the original (.PDF) on 2007-02-21. Retrieved 2008-02-27. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - William Davies, Petroleum Tables; being some useful Tables used for Ascertaining the Weights and Measures of Petroleum Cargoes, and a Table of Distances (London: Goodman, Burnham, and Company, 1903)

- The Petroleum World, Vol. 12 (1915), p. 146

References

- Cambridge Systematics (1998). Multimodal corridor and capacity analysis manual. Transportation Research Board. ISBN 978-0-309-06072-1.

- Central Intelligence Agency. CIA World Factbook 2008. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 1-60239-080-0. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (1911). "Petroleum". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 316–322. OCLC 70608430. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (1911). "Ship". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 881–889. OCLC 70608430. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- Hayler, William B.; Keever, John M. (2003). American Merchant Seaman's Manual. Centerville, MD: Cornell Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87033-549-9.

- Morrell, Robert W. (1931). Oil Tankers (Second ed.). New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Company.

- Muller, Gerhardt (1998). "Transportation Modes". In Tompkins, James A.; Smith, Jerry D. (eds.). Warehouse Management Handbook (2nd ed.). Tompkins Press. ISBN 978-0-9658659-1-3.

- Muller, Gerhardt (1995). Intermodal freight transportation (3rd ed.). Intermodal Association of North America.

- Seyoum, Belay (2008). "Trade documents and Transportation". Export–Import Theory, Practices, and Procedures (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-7890-3419-9.

- Turpin, Edward A.; McEwen, William A. (1980). Merchant Marine Officers' Handbook (Fourth ed.). Centreville, MD: Cornell Maritime Press. ISBN 0870333798.

- Wiltshire, Andrew (2008). Looking Back at Classic Tankers. Bristol, England: Bernard McCall. ISBN 9781902953366.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tankers. |

- ship-photos.de: Private homepage of categorized ship photos including tankers of all kinds