Car float

A railroad car float or rail barge is an unpowered barge with railway tracks mounted on its deck. It is used to move rolling stock across water obstacles, or to locations they could not otherwise go, and is towed by a tugboat or pushed by a towboat. As such, the car float is a specialised form of the lighter,[1] as opposed to a train ferry, which is self-powered.

Historical operations

U.S. East Coast

During the Civil War, Herman Haupt used huge barges fitted with tracks to enable military trains to cross the Rappahannock River in support of the Army of the Potomac.[2]

Beginning in the 1830s, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) operated a car float across the Potomac River, just south of Washington, D.C., between Shepherds Landing on the east shore, and Alexandria, Virginia on the west. The ferry operation ended in 1906.[3] The B&O operated a car float across the Baltimore Inner Harbor until the mid-1890s. It connected trains from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C. and points to the west. The operation ended after the opening of the Baltimore Belt Line in 1895.[3]

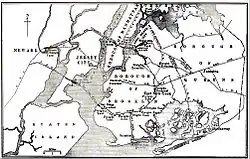

The Port of New York and New Jersey had many car float operations, which lost ground to the post-World War II expansion of trucking, but held out until and the rise of containerization in the 1970s.[4]

These car floats operated between the Class 1 railroads terminals on the west bank of Hudson River in Hudson County, New Jersey and the numerous online and offline terminals located in Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, the Bronx, and Manhattan.[5][6] Class 1 railroads in the New York Harbor area providing car float services were:

- Baltimore and Ohio Railroad[7][8]

- Central Railroad of New Jersey[9][10]

- Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad[11][12]

- Erie Railroad and Erie Lackawanna Railroad[13][14]

- Lehigh Valley Railroad[15][16]

- Long Island Rail Road[17][18]

- New York Central Railroad[19][20]

- New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad[21][22]

- Pennsylvania Railroad[23][24]

- Reading Railroad[25]

As well as the offline terminal railroads:

- Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal[26]

- Bush Terminal/Industry City[27][28]

- Brooklyn Army Terminal

- Hoboken Manufacturers Railroad[29]

- Jay Street Connecting Railroad[30]

- New York Dock Railway[31][32]

- Pouch Terminal[33]

- East Jersey Railroad and Terminal Co.[33]

Car float service was also provided to many pier stations and waterfront warehouse facilities (that did not engage in car floating service personally) by the above-mentioned railroads.

At their peak, the railroads had 3,400 employees operating small fleets totalling 323 car floats, plus 1,094 other barges, towed by 150 tugboats between New Jersey and New York City.

Abandoned float bridges are preserved as part of this history at:

- Gantry Plaza State Park in Long Island City, Queens; (former Long Island Railroad),

- West 26th Street float bridge (former Baltimore & Ohio) and the only surviving wood Howe truss float bridge in New York Harbor

- North River Pier 66a, and 69th Street Transfer Bridge (former New York Central)

Several other abandoned but unrestored float bridges exist in other locations around New York Harbor. A complete list is available at Surviving Float Bridges of New York Harbor

Freight cars do not run in the East River Tunnels nor the North River Tunnels (under the Hudson River), in part due to inadequate tunnel clearances of the New York Tunnel Extension.

The Bay Coast Railroad formerly operated a 2-barge car float connecting Virginia's Eastern Shore with the city of Norfolk, Virginia across the Chesapeake Bay.

U.S. Midwest

Between 1912–1936, the Erie Railroad operated a car float service on the Chicago River in Chicago, Illinois.[34]

U.S. West Coast

- Santa Fe Railroad: San Francisco

- Southern Pacific Railroad: (?)

- Union Pacific Railroad: (?)

- Western Pacific Railroad: San Francisco

- Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad: Seattle; Tacoma, Washington; Bellingham, Washington; Port Townsend, Washington

- Seattle and North Coast Railroad: Seattle; Port Townsend, Washington

Canada

- Various inland lakes of British Columbia (Okanagan, Arrow, Kootenay) (Canadian National Railway and CPR)

- Port Maitland, Ontario – Erie, Pennsylvania (TH&B Railway)

- Port Burwell, Ontario – Ashtabula, Ohio (CN)

- Cobourg, Ontario – Rochester, New York (Ontario Car Company)

- Sarnia, Ontario – Port Huron, Michigan – rail-barge – (CN, until the opening of the Paul Tellier Tunnel). The rail ferries Pere Marquette 12 and Pere Marquette 10 were converted to barges (PM 10 in 1974, PM 12 in the 1980s) and used until 1995 to carry dangerous cargoes and oversize cars.[35]

- Windsor, Ontario – Detroit, Michigan (Grand Trunk, CN, CPR, Michigan Central, Wabash, until the 1980s)

- BC Rail. until 1955 railcars were barged from North Vancouver to Squamish.

- A large number of isolated BC pulp mills had chemicals and freight moved by car floats.

Existing operations

Alaska

The Alaska Railroad provides the Alaska Rail Marine rail barge service from downtown Seattle to Whittier on the central Alaskan mainland.[36] Additionally, CN Rail provides the Aquatrain rail barge service from Prince Rupert, British Columbia to Whittier.[37]

New York / New Jersey

The only remaining car float service in operation in the Port of New York and New Jersey is operated by New York New Jersey Rail. This company, operated by the bi-state government agency Port Authority of New York & New Jersey is the successor to the New York Cross Harbor Railroad. Car float service operates between 65th Street / Bay Ridge Yard in Brooklyn and Greenville Yard in Jersey City, New Jersey.[38]

See also

- Bay Ridge Branch

- Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel (proposed)

- Ferry slip (includes examples of rail ferry and barge slips)

- New York tugboats

- Santa Fe Dock and Channel Company

References

- Lederer, Eugene H. (1945). Port Terminal Operation: Port Terminal Management, Stevedoring, Stowage, Lighterage and Harbor Boats. New York, NY: Cornell Maritime Press. pp. 291–292.

- Wolmar, Christian (2012). Engines of War. London: Atlantic Books. p. 49. ISBN 9781848871731.

- Harwood, Jr., Herbert H. (1979). Impossible Challenge: The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in Maryland. Baltimore, MD: Barnard, Roberts. ISBN 0-934118-17-5.

- Cudahy, Brian J. (2006). Box Boats: How Container Ships Changed the World. New York, NY: Fordham University Press. pp. 45–47. ISBN 0-8232-2568-2.

- Flagg, Thomas R. (2000). New York Harbor Railroads in Color, Volume 1. Scotch Plains, NJ: Morning Sun Books. ISBN 1-58248-082-6.

- Flagg, Thomas R. (2002). New York Harbor Railroads in Color, Volume 2. Scotch Plains, NJ: Morning Sun Books. ISBN 1-58248-048-6.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 16–23.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 26–29.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 24–33.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 38–39.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 34–45.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 40–51.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 46–55.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 52–57.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 56–61.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 58–63.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 62–65.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 64–67.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 66–83.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 68–93.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 84–91.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 94–97.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 92–101.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 98–109.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 30–37.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 110–116.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 118–125.

- Flagg, 2002, pp. 120–127.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 126–127.

- Flagg, 2002, p. 118.

- Flagg, 2000, pp. 110–117.

- Flagg, 2002, p. 119.

- Flagg, 2002, p. 117.

- Sennstrom, Bernard H. (1992). "Erie Railroad's Chicago River Service". The Diamond. 7 (1): 4–10.

- The Pere Marquette Marine Fleet, Pere Marquette Historical Society, 10-MAY-2011, accessed July 16, 2012

- Alaska Rail Marine Archived December 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Aqua train

- "Route Map". New York New Jersey Rail, LLC. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- Trains (Magazine) February 2009 p9

External links

- Railroad ferry, Hudson River, New York, Andreas Feininger, 1940. Still Photograph Archive, George Eastman House, Rochester, NY.

- NYNJ Rail – official site

- Industrial & Offline Terminal Railroads of Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, Bronx & Manhattan