The Heart of Thomas

The Heart of Thomas (Japanese: トーマの心臓, Hepburn: Tōma no Shinzō) is a 1974 Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Moto Hagio. Originally serialized in the weekly manga magazine Shūkan Shōjo Comic, the series follows the events at a German all-boys gymnasium following the suicide of student Thomas Werner. The series draws inspiration from the Bildungsroman genre, the works of Hermann Hesse, and the 1964 film Les amitiés particulières, and is noted as one of the earliest manga in the shōnen-ai (male-male romance) genre.

| The Heart of Thomas | |

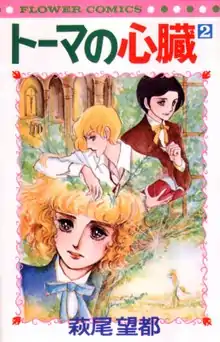

The cover of the second tankōbon, featuring Erich (left), Oskar (center), and Juli (right) | |

| トーマの心臓 (Tōma no Shinzō) | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Shōnen-ai[1] |

| Created by | Moto Hagio |

| Manga | |

| Published by | Shōgakukan |

| English publisher | |

| Imprint | Flower Comics |

| Magazine | Shūkan Shōjo Comic |

| Demographic | Shōjo |

| Original run | May 5, 1974 – December 22, 1974 |

| Volumes | 3 (1 in North America) |

| Sequels & related works | |

| |

| Adaptations | |

| |

The Heart of Thomas was developed and published during a period of immense change and upheaval for shōjo manga (girls' comics) as a medium, characterized by the emergence of new aesthetic styles and more narratively complex stories. This change came to be embodied by a new generation of shōjo manga artists collectively referred to as the Year 24 Group, of which Hagio was a member. The series was originally developed by Hagio as a personal project that she did not expect would ever be published. After changing publishing houses from Kodansha to Shogakukan in 1971, Hagio published a loosely-adapted one-shot (standalone single chapter) version of The Heart of Thomas titled The November Gymnasium before publishing the full series in 1974.

While The Heart of Thomas was initially poorly received by readers, by the end of its serialization it was among the most popular series in Shūkan Shōjo Comic. Today, The Heart of Thomas is considered a seminal work of both shōnen-ai and shōjo manga. It has attracted significant scholarly interest, with critics exploring the series' depiction of gender, religion, and spiritual love in their analysis of the work. It inspired multiple works, and has been adapted into a film, a stage play, and a novel. In North America, an English-language translation of The Heart of Thomas, translated by Rachel Thorn, was published by Fantagraphics Books in 2013.

Synopsis

The series is set in the mid-20th century, primarily at the fictional Schlotterbach Gymnasium in the Karlsruhe region of Germany, located on the Rhine between the cities of Karlsruhe and Heidelberg.[2][3]

During Easter holidays, Schlotterbach student Thomas Werner commits suicide by throwing himself from a bridge. His classmate Julusmole "Juli" Bauernfeind receives a posthumous suicide letter from Thomas wherein Thomas professes his love for him; Thomas had unrequited romantic feelings for Juli, who had previously rejected his affections. Though Juli is outwardly unmoved by the incident, he is privately wracked with guilt over Thomas' death. He confides in his roommate Oskar Reiser, who is secretly in love with Juli.

Erich Frühling, a new student who bears a very close physical resemblance to Thomas, arrives at Schlotterbach shortly thereafter. Erich is irascible and blunt, and resents being frequently compared to the kind and genteel Thomas. Juli believes that Erich is Thomas' malevolent doppelgänger who has come to Schlotterbach to torment him, and tells Erich that he intends to kill him. Oskar attempts to de-escalate the situation, and befriends Erich. They bond over their troubled family contexts: Erich harbors an unresolved Oedipus complex towards his recently-deceased mother, while Oskar's mother was murdered by her husband after he discovered Oskar was the product of an extramarital affair.

It is gradually revealed that the root of Juli's anguish was his attraction to both Thomas and Siegfried Gast, the lattermost of whom was a delinquent student at the school. Juli chose to pursue Siegfried over Thomas, who physically abused Juli by caning his back and burning his chest with a cigarette to the point of scarring, and is implied to have raped him.[4][5] The incident traumatized Juli; likening himself to a fallen angel who has lost his "wings", Juli came to believe he was unworthy of being loved, which prompted his initial rejection of Thomas. Juli, Oskar, and Erich ultimately resolve their traumas and form mutual friendships. Having made peace with his past, Juli accepts Thomas' love and leaves Schlotterbach to join a seminary in Bonn, so that he may be closer to Thomas through God.

Characters

Primary characters

- Thomas Werner (トーマ・ヴェルナー, Tōma Verunā)

- A thirteen year old student at Schlotterbach, beloved by his peers, who refer to him by the nickname "Fräulein". He harbors romantic feelings for Juli, but upon declaring his love for him, is rejected. His suicide, ostensibly motivated by this rejection, serves as the inciting incident for the plot of the series.

- Julusmole Bauernfeind (ユリスモール・バイハン, Yurisumōru Baihan)

- A fourteen year old student at Schlotterbach, nicknamed Juli (ユーリ, Yūri). The son of a German mother and a Greek father, he faces discrimination from his maternal grandmother as a result of his mixed heritage. Thus, he strives to be a perfect student so that he can one day be someone worth admiring regardless of his physical characteristics: he is the top pupil at Schlotterbach, a prefect, and the student head of the school library. The abuse he suffered at the hands of Siegfried led him to believe that he is unworthy of love, and to reject Thomas's romantic advances.

- Oskar Reiser (オスカー・ライザー, Osukā Raizā)

- Juli's fifteen year old roommate. He is the illegitimate child of his mother Helene and Schlotterbach headmaster Müller; when Helene's husband Gustav discovered that Oskar was not his child, he shot and killed her. Gustav pretended the death was an accident and abandoned Oskar at Schlotterbach to be cared for by the headmaster. Oskar is aware of the truth of his parentage, but does not admit so openly, and dreams of one day being adopted by Müller. Though Oskar behaves like a delinquent, he possesses a strong sense of responsibility for others: he is one of the few who knows about Juli's past, and becomes one of the first students to befriend Erich. Oskar is in love with Juli, but he rarely admits so and never pushes himself on him.

- Erich Frühling (エーリク・フリューリンク, Ēriku Furyūrinku)

- A fourteen year old student from Cologne who arrives at Schlotterbach shorty after Thomas' death, and who strongly resembles Thomas. Irascible, blunt, and spoiled, he suffers from neurosis and fainting spells caused by an unresolved Oedipus complex: he deeply loves his mother Marie, who dies in a car accident shortly after his arrival at Schlotterbach. During this time, Juli comforts him and the two become close; Erich eventually falls in love with Juli, and pursues him even as Juli rebuffs him out of guilt for Thomas. By the end of the series, Erich and Juli make peace.

Secondary characters

- Ante Löwer (アンテ・ローエ, Ante Rōhe)

- A thirteen year old student at Schlotterbach who is in love with Oskar, and harbors jealously towards Juli as the target of Oskar's affections. He made a bet with Thomas to seduce Juli in hopes of distancing Oskar and Juli; unaware of Thomas' genuine feelings for Juli, he blamed himself when the bet backfired and Thomas killed himself as a result of Juli's rejection. Ante is calculated and spiteful, but eventually matures and admits to the consequences of his actions.

- Siegfried Gast (サイフリート・ガスト, Seifuriito Gasuto)

- A former student at Schlotterbach. He is renowned for his intelligence, delinquency, and debauchery, and proclaims himself to be greater than God. Prior to the events of the series, Juli found himself attracted to Siegfried against his better judgement, leading to an incident wherein he was abused and tortured by Siegfried and several other upperclassmen. Siegfried and the upperclassmen were expelled from Schlotterbach as a result.

- Julius Sidney Schwarz (ユーリ・シド・シュヴァルツ, Yūri Shido Shuvarutsu)

- The lover of Erich's mother Marie at the time of her death; a car accident in Paris kills Marie and causes Julius to lose one of his legs. He visits Erich and offers to adopt him, to which Erich consents.

- Gustav Reiser (グスターフ・ライザー, Gusutāfu Raizā)

- Oskar's legal father. Upon learning that Oskar is not his biological child, he murdered his wife and sent Oskar to Schlotterbach before fleeing to South America.

- Müller (ミュラー, Mura)

- The headmaster of Schlotterbach. A former friend of Gustav's, and Oskar's biological father.

Development

Context

Moto Hagio made her debut as manga artist in 1969 publishing short stories.[6] Shōjo manga (girls' comics) of this era were typically sentimental or humorous in tone, marketed towards elementary school-aged girls, and were often centered on familial drama or romantic comedy;[7][8] as Hagio's artistic and narrative style deviated from shōjo manga that were typical of the 1960s, she faced persistent early difficulties in finding publishers for her long-form serialized work.[6] Hagio's debut as a manga artist occurred contemporaneously with a period of immense change and upheaval for shōjo manga as a genre: the early 1970s saw the emergence of new aesthetic styles that differentiated the genre from shōnen manga (manga for boys), as well as more narratively complex stories that focused on social issues and sexuality.[9]

This change came to be embodied by a new generation of shōjo manga artists collectively referred to as the Year 24 Group, of which Hagio was a member. The group contributed significantly to the development of shōjo manga by expanding the genre to incorporate elements of science fiction, historical fiction, adventure fiction, and homoeroticism (both male-male and female-female).[10] Notable works created by the Year 24 Group that were relevant to the development of The Heart of Thomas include In The Sunroom by Keiko Takemiya, which would become the first manga in the shōnen-ai genre; the series was further noted for having male protagonists, which was uncommon for shōjo manga at the time.[11] The Rose of Versailles by Riyoko Ikeda, which began serialization in the manga magazine Margaret in May 1972, became the first major commercial success in the shōjo genre, and proved the genre's viability as a commercial category.[12] Hagio herself began publishing The Poe Clan in March 1972 in Bessatsu Shōjo Comic; the series was not strictly a serial, but rather a series of interrelated narratives featuring recurring characters which functioned as standalone stories.[13]

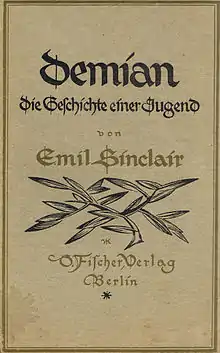

Production

In 1970, Hagio befriended Norie Masuyama and manga artist Keiko Takemiya. Masuyama is credited with introducing Hagio and Takemiya to literature, music, and films that would come to heavily influence their manga: Demian, Beneath the Wheel, and Narcissus and Goldmund by Herman Hesse, as well as other novels in the Bildungsroman genre recommended by Masuyama, came to influence Hagio generally and The Heart of Thomas specifically.[14][15][16] Hagio has stated that Hesse's works "opened up one by one the dams that had stopped up the water [...] I heard a voice saying 'yes, you can write. Yes, you can express yourself the way you like. Yes, you can exist.'"[14] That same year, Hagio and Takemiya watched the 1964 Jean Delannoy film Les amitiés particulières, which depicts a tragic romance between two boys in a French boarding school. The film inspired Takemiya to create In The Sunroom, while Hagio began to create The Heart of Thomas as a personal project that she did not expect would ever be published.[13][17]

In 1971, Hagio changed publishing houses from Kodansha to Shogakukan, granting her greater editorial freedom and leading her to publish a loosely-adapted one-shot version of The Heart of Thomas.[13] Initially, Hagio changed the protagonists of the series from boys to girls; unsatisfied with the resulting story, she maintained the male protagonists of the original series and published the adaptation as The November Gymnasium in Bessatsu Shōjo Comic in November 1971.[13] The November Gymnasium depicts a love story between Erich and Thomas, and ends with the latter's death; Oskar also appears, having previously appeared in Hagio's Hanayome wo Hirotta Otoko (花嫁をひろった男) in April 1971, and who would later appear in 3-gatsu Usagi ga Shūdan de (3月ウサギが集団で) in April 1972 and Minna de Ocha o (みんなでお茶を) in April 1974.[18]

Release

Following the critical and commercial success of The Rose of Versailles at rival publisher Shueisha, Shūkan Shōjo Comic editor Junya Yamamoto asked Hagio to create a series of similar length and complexity to be serialized over the course of two to three years.[19] Having already drawn roughly 200 pages of The Heart of Thomas, Hagio submitted the series; the first chapter was published in the magazine on May 5, 1974.[19] Three weeks into its serialization, a reader survey found that The Heart of Thomas was the least-popular series in Shūkan Shōjo Comic, prompting editors at the magazine to request that Hagio amend the original two- to three-year timeline for the series to four to five weeks.[13][19] Hagio negotiated to allow serialization of The Heart of Thomas to continue for an additional month, stating that if the reception was still poor after that time, she would finish the story prematurely.[19]

In June 1974, the first tankōbon (collected edition) of Hagio's The Poe Clan was published: it sold 300,000 copies in three days, which at the time made it the best-selling shōjo manga in history.[20] Shogakukan encouraged Hagio to conclude The Heart of Thomas to focus on The Poe Clan, though Hagio insisted on continuing the series.[20] The success of The Poe Clan drew attention to The Heart of Thomas, and by the end of the summer, The Heart of Thomas was ranked as the fifth most popular serialization in Shūkan Shōjo Comic.[21] Assisted by Yukiko Kai, Hagio continued serialization of The Heart of Thomas.[22] The series concluded on December 22, 1974, with 33 weekly chapters published in Shūkan Shōjo Comic.[23] At the time, original manga artwork did not necessarily remain the property of the artist; in the case of The Heart of Thomas, the original artwork for the frontispiece of each chapter were distributed as rewards for a contest in the magazine.[23] In 2019, Shogakukan launched a campaign through its magazine Monthly Flowers to recover the original frontispieces for The Heart of Thomas.[23][24]

Editions

Upon its conclusion, Shogakukan collected The Heart of Thomas into three tankōbon published in January, April, and June 1975; they are respectively numbers 41, 42, and 43 of the Flower Comics collection.[25][26][27] The series has been regularly re-printed by Shogakukan.[13] In the West, The Heart of Thomas was not published until the 2010s. On September 14, 2011, Fantagraphics Books announced that it had acquired the license to The Heart of Thomas for release in North America.[28] The single-volume hardcover omnibus, translated into English by Rachel Thorn, was released on January 18, 2013.[29]

Sequels and related works

By the Lake: The Summer of Fourteen-and-a-Half-Year-Old Erich (湖畔にて – エーリク十四と半分の年の夏, Kohan nite – Ēriku Jūyon to Hanbun no Toshi no Natsu) is a one-shot sequel to The Heart of Thomas. The series follows Erich as he vacations on Lake Constance with Julius, who is now his adopted father; he later receives a letter from Juli, and is visited by Oskar.[2][30] The manga was published in 1976 in the illustration and poetry book Strawberry Fields (ストロベリー・フィールズ) published by Shinshokan.[31]

The Visitor (訪問者, Hōmonsha) is a one-shot prequel to The Heart of Thomas. The story focuses on Oskar: first while he is on vacation with Gustav prior to arriving at Schlotterbach, and later when he meets Juli for the first time.[32] The manga was published in the spring 1980 issue of Petit Flower.[33]

The November Gymnasium (11月のギムナジウム, 11-gatsu no Gymnasium) is an early version of The Heart of Thomas that loosely adapts the themes and characters of the then-unpublished manga into an original one-shot story.[34] It focuses on a romance between Erich and Thomas, and ends with the latter's death. The November Gymnasium was published in Bessatsu Shōjo Comic in November 1971.[33]

Analysis and themes

Visual style

In The Heart of Thomas, Hagio develops the visual grammar of shōjo manga of the 1950s and 1960s – which was largely inspired by jojōga (lyrical pictures) and prewar girls' magazines – into a new and original style.[35] Deborah Shamoon of the National University of Singapore specifically highlights the use of stream of consciousness, open panels, symbolic imagery, emotive backgrounds, and layering of visual elements as hallmarks of this new style.[36] Shamoon argues that these techniques create a three-dimensional effect that "lends both literal and symbolic depth to the story."[37] Bill Randall of The Comics Journal similarly comments on Hagio's use of stream of consciousness, noting that the internal monologues of the protagonists are written separately from speech balloons;[38] the sentences are fragmented and scattered across the page, which Shamoon compares to poetry and the writing style of Nobuko Yoshiya.[36] These monologues are accompanied by images, motifs, and backgrounds that often extend beyond the edges of panels or overlap to form new compositions.[36] Shamoon describes these compositions as "melodramatic stasis" – the action stops so that the monologue and images can communicate the inner pathos of the characters.[37] Randall considers how these moments allow the reader to directly access the emotions of the characters, "encouraging not a distanced consideration of the emotion, but a willing acceptance" of them.[38]

Gender

Traditionally in manga, the shape and size of a character's face and eyes are used to mark their age and sex: the younger and more feminine a character is, the rounder their face and the larger their eyes.[39] The male students of Schlotterbach Gymnasium are depicted as having the same face and eye shape as the young girls who infrequently appear in The Heart of Thomas, with only clothing and hairstyles visually distinguishing boys from girls. Consequently, the male characters who serve as the protagonists of The Heart of Thomas (and of Hagio's works generally)[40] are often interpreted by critics to be allegorical women.[39] Kaoru Tamura of Washington University in St. Louis compares the androgynous appearance of the boys of The Heart of Thomas to Cedric Errol of Little Lord Fauntleroy, which was translated into Japanese by Wakamatsu Shizuko; while it is not certain that Hagio read the work, Tamura considers it extremely likely, considering the aesthetic similarities.[41] The sole exception to this feminization is Siegfried, who has typically male physical characteristics; Nobuko Anan of the University of London argues this marks Siegfried as a deviant presence in a world of girls,[42] with his assault of Juli serving as an allegory for women who are raped.[39] Juli's ability to overcome this trauma through his friendship with Oskar and Erich is compared by Anan to women who overcome the trauma of rape with the support of other women.[39]

When adapting The Heart of Thomas as The November Gymnasium, Hagio relocated the setting of the story to an all-girls boarding school but decided the environment was too restrictive, comparing it to being "bound by a witch's spell," and that the "unknown world" of a boys' school would be more interesting.[43] Her decision to use male protagonists to tell the story of The Heart of Thomas has been the subject of debate by critics. When asked why she chose to create a shōjo manga series with an all-male cast, Hagio stated that "boys in shōjo manga are at their origin girls, girls wishing to become boys and, if they were boys, wanting to do this or do that. Being a boy is what the girls admire."[44] Writing for The Atlantic, Noah Berlatsky argues that Hagio subverts the "Orientalist harem fantasy" by objectifying male European characters.[45] James Welker of Kanagawa University suggests that Hagio is a victim of "lesbian panic", and that she was uncomfortable with creating a manga that openly portrayed a lesbian relationship; Welker cites the fact that The Heart of Thomas attracted a significant lesbian readership,[46] and that Hagio used the adjective iyarashii (嫌らしい, lit. "unpleasant" or "obscene") to describe the female version of The November Gymnasium, as evidence of his claim.[43] Shamoon counters that Hagio was likely referencing the Class S genre of shōjo manga that depicts intimate relationships between female characters, and that her use of iyarashii may have been in reference to the old-fashioned and sclerotic conventions of that genre.[47]

Religion

The Heart of Thomas draws heavily from Gothic art, with frequent use of angelic figures and references to Biblical stories.[16] The Gothic aesthetic was common in the works that influenced The Heart of Thomas, such as the novels of Herman Hesse.[41] Hagio is neither Christian nor monotheist, and critics have noted that her presentation of Christian concepts often draws inspiration from animism as well as the Japanese polytheism of Shintoism and Buddhism.[49] The spirit of Thomas is represented throughout the series as Amor, the Roman god of love; Oskar remarks to Erich that Thomas was possessed by the spirit of Amor, and that his suicide released the spirit. While Amor is often depicted as an angel in Western art, Hagio manifests him in multiple forms, such as the air, a landscape,[50] or as temporarily possessing a character.[51] Various figures from Christian and Greek mythology also manifest in this manner, such as the angel Gabriel[37] and the Moirai.[52]

Suicide and spiritual love

Thomas' suicide as an act of love and self-sacrifice for Juli has been cited as the most apparent example of Hesse's impact on The Heart of Thomas. Like Hesse's Demian, The Heart of Thomas explores the concept of rebirth through destruction, though it reverses Demian's chronology to begin rather than conclude the story with an act of suicide.[53] Thorn notes this reversal with regards to the influence of the film Les amitiés particulières, which also inspired the manga: while Les amitiés particulières concludes with a suicide, "the cause of which is obvious, Hagio begins with a suicide, the cause of which is a mystery."[13] Commenting on the unresolved nature of Thomas' suicide in a 2005 interview with The Comics Journal, Hagio stated:

"If I had written [The Heart of Thomas] after the age of thirty, I probably would have worked out some logical reason for [Thomas] to die, but at the time I thought, 'He doesn't need a reason to die.' [Laughs.] I could have said that he died because he was sick and didn't have long to live anyway, or something like that. At the time, I thought, how one lives is important, but how one dies might be important, too, and so that's how I wrote it. In a sense, that mystery of why he had to die is never solved, and I think that unsolved mystery is what sustains the work."[17]

Manga critic Aniwa Jun interprets Thomas' suicide not as a selfish act motivated by Juli's rejection, but as a "longing for super power, yearning for eternity, an affirmation and sublimation of life to a sacred level."[54] Shamoon concurs that Thomas' death is "not so much as an act of despair over his unrequited love for Juli, but as a sacrifice to free Juli’s repressed emotions."[55] She argues that Juli as a character "represents the triumph of spiritual love over the traumas of adolescence and specifically the threat of sexual violence,"[56] and that his decision to join a seminary at the conclusion of the series represents his acceptance of "spiritual love (ren'ai) at its most pure [...] a transcendent, divine experience, separated from physical desires."[55] Thorn further contrasts the focus on spiritual love in The Heart of Thomas to Kaze to Ki no Uta and the works of Keiko Takemiya, which focus primarily on physical love.[17]

Reception and legacy

The Heart of Thomas is considered a seminal work of both shōnen-ai and shōjo manga,[45] and came to strongly influence shōjo manga works that followed it. Randall notes how many of the stylistic hallmarks of the series, such as characters depicted with angel's wings or surrounded by flower petals, became standard visual tropes in the shōjo genre.[38] Shamoon argues that the use of interior monologue in The Heart of Thomas, which was later adapted by other series in shōjo genre, became the main marker distinguishing shōjo manga from other types of manga.[36] She adds that The Heart of Thomas marked the transition of shōjo manga from a genre that primarily focused on familial love, as in titles such as Paris-Tokyo by Macoto Takahashi, to a genre focused on romantic love.[16] Thorn notes that the themes and characters of The Heart of Thomas are also present in Hagio's 1992 manga series A Cruel God Reigns, describing the series as "the adult version" of The Heart of Thomas."[17]

In reviews of The Heart of Thomas in the mainstream and enthusiast press, critics have praised the series' artwork, narrative, and writing. Writing for Anime News Network, Jason Thompson praises its "'70s shojo artwork", along with the "dreamlike sense of unreality" in Hagio's dialogue.[57] In a separate review for Anime News Network, Rebecca Silverman similarly praises the "willowy" and dramatic 1970s-style artwork, particularly Hagio's use of collage imagery,[58] Writing for Comics Alliance, David Brothers favorably compares the melodrama of the series to Chris Claremont's Uncanny X-Men and commends its character-driven drama.[59] Publishers Weekly described the series' romance elements as "engaging but nearly ritualized," but praised Hagio's "clear art style and her internally dark tone."[60] In the Japanese press, Rio Wakabayashi of Real Sound praised the series for raising shōjo manga to the "realm of literature" through the depth of its plot and characterization,[61], while Haru Takamine of Christian Today cited the series as a positive depiction of Christianity in manga through its portrayal of sacrifice and unconditional love.[62]

As one of the first ongoing serialized manga in the shōnen-ai genre, The Heart of Thomas is noted for its impact on the contemporary boys' love (BL) genre. In his survey of BL authors, sociologist Kazuko Suzuki found that The Heart of Thomas was listed as the second-most representative work in the genre, behind Kaze to Ki no Uta by Keiko Takemiya.[63] The manga has attracted significant academic interest, and during the 2010s was one of the most studied and analyzed manga by Western academics.[64] Shamoon notes that much of the Western analysis of The Heart of Thomas examines the manga from the perspective of contemporary gay and lesbian identity, which she argues neglects the work's focus on spiritual love and homosociality in girls' culture.[55]

Adaptations

The Heart of Thomas was loosely adapted into the 1988 live-action film Summer Vacation 1999, directed by Shusuke Kaneko and written by Rio Kishida. The film follows four boys who live alone in an isolated and seemingly frozen-in-time boarding school; the film utilizes a retrofuturistic style, with Kaneko stating that as The Heart of Thomas is not a realist story, he chose to reject realism for its adaptation. The four principal characters are portrayed by female actors in breeches roles, who are dubbed over by voice actors performing in male voices.[65] The film was adapted into a novel by Kishida, which was published in 1992 by Kadokawa Shoten.[66]

In 1996, the theater company Studio Life adapted The Heart of Thomas into a stage play under director Jun Kurata. The adaption is considered a turning point for the company: it began staging plays with male actors exclusively, integrated shingeki (realist) elements into its productions, and changed its repertoire to focus primarily on tanbi (male-male romance) works.[67] The Heart of Thomas became one of Studio Life's signature plays, and is regularly performed by the company.[68] The Visitor, the prequel to The Heart of Thomas, has also been adapted by the company.[69]

Writer Riku Onda began to adapt The Heart of Thomas into a prose novel in the late 1990s, but ultimately deviated from the source material to create the original novel Neverland (ネバーランド, Nebārando), which was serialized in the magazine Shōsetsu Subaru from May 1998 to November 1999 and published as a novel in 2000.[69] Hiroshi Mori, who cites Hagio as among his major influences,[13] adapted the manga into the novel Tōma no Shinzō – Lost Heart for Thoma (トーマの心臓 – Lost heart for Thoma), a novel that recounts the events of the manga from Oskar's point of view.[69] It was published on July 31, 2009 by the publishing house Media Factory.[70] The cover and frontispiece of the novel are illustrated by Hagio,[71] while prose from the original manga is inserted into the novel as epigraphs to each chapter.[69]

References

- "The Heart of Thomas by Moto Hagio". Fantagraphics Books. January 3, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- Hagio 2020, p. 145.

- Hagio 2012, p. 152.

- Tamura 2019, p. 40.

- Hori 2013, p. 304.

- Tamura 2019, p. 27.

- Thorn 2010, p. V.

- Maréchal 2001.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 102.

- Toku 2004.

- Nakagawa, Yūsuke (October 15, 2019). "「COM」の終焉と「美少年マンガ」の登場". Gentosha Plus (in Japanese). Gentosha. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 119.

- Hagio 2013, Introduction by Rachel Thorn.

- Tamura 2019, p. 28.

- Welker 2015a, p. 48-50.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 105.

- Thorn 2005.

- Hagio 2019, p. 126.

- Tamura 2019, p. 5.

- Nakagawa, Yūsuke (October 29, 2019). "新書判コミックスで変わる、マンガの読み方". Gentosha Plus (in Japanese). Gentosha. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019.

- Tamura 2019, p. 6.

- Hagio 2019, p. 162.

- Hagio 2019, p. 123.

- Loveridge, Lynzee (January 2, 2019). "Monthly Flowers Editors Ask for Help to Locate Original The Heart of Thomas Manga Art". Anime News Network. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- "トーマの心臓 1". National Diet Library (in Japanese). Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- "トーマの心臓 2". National Diet Library (in Japanese). Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- "トーマの心臓 3". National Diet Library (in Japanese). Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- Baehr, Mike. "Moto Hagio's Heart of Thomas coming in Summer/Fall 2012". Fantagraphics Books. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- "Fantagraphics Books Presents Moto Hagio's The Heart of Thomas" (Press release). November 27, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- Hagio 2019, p. 104.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 185.

- Hagio 2019, p. 108.

- Hagio 2019, p. 185.

- Hagio 2019, p. 114.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 113.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 114.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 116.

- Randall 2003.

- Anan 2016, p. 83.

- Hori 2013, p. 152.

- Tamura 2019, p. 37.

- Anan 2016, p. 84.

- Welker 2006, p. 858.

- Tamura 2019, p. 49.

- Berlatsky 2013.

- Welker 2006, p. 843.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 107.

- Tamura 2019, p. 32.

- Tamura 2019, p. 34, 37, 39.

- Tamura 2019, p. 36.

- Tamura 2019, p. 39.

- Tamura 2019, p. 47.

- Tamura 2019, p. 31.

- Tamura 2019, p. 35.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 106.

- Shamoon 2012, p. 109.

- Thompson 2012.

- Silverman 2013.

- Brothers 2013.

- "Comic Book Review: The Heart of Thomas". Publishers Weekly. January 21, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Wakabayashi 2020.

- Takamine 2014.

- Suzuki 2015, p. 96.

- Taylor 2006, p. 36.

- Anan 2016, p. 108.

- Welker 2006, p. 851.

- Anan 2016, p. 100.

- Anan 2016, p. 65.

- Welker 2015b.

- "トーマの心臓". National Diet Library (in Japanese). Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- "森博嗣が書く「トーマの心臓」が7月31日に発売". Comic Natalie (in Japanese). July 1, 2007. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

Bibliography

- Primary sources

- Hagio, Moto (2010). A Drunken Dream and Other Stories. Translated by Thorn, Rachel. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books. pp. XXIX-256. ISBN 978-1-60699-377-4.

- Thorn, Rachel (2010). "The Magnificent Forty-Niners". A Drunken Dream and Other Stories. pp. V–VII.

- Hagio, Moto (2012). Le cœur de Thomas (in French). Translated by Sekiguchi, Ryoko; Uno, Takanori. Paris: Kazé. ISBN 978-2-8203-0534-3.

- Hagio, Moto (2013). The Heart of Thomas. Translated by Thorn, Rachel. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 978-2-8203-0534-3.

- Hagio, Moto (2019). "『トーマの心臓』の世界". デビュー50周年記念『ポーの一族』と萩尾望都の世界 (in Japanese). Tokyo: Kawade Shobo Shinsha. ISBN 978-4-09-199063-1.

- Hagio, Moto (2020). 萩尾望都 作画のひみつ (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shinchōsha. ISBN 978-4-10-602293-7.

- Books and articles

- Anan, Nobuko (2016). "Girlie Sexuality: When Flat Girls Become Three-Dimensional". Contemporary Japanese Women's Theater and Visual Arts: Performing Girls' Aesthetics. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-55706-6.

- Hori, Hikari (2013). "Tezuka, Shōjo Manga, and Hagio Moto". Mechademia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 8: 299–311. doi:10.1353/mec.2013.0012.

- Maréchal, Béatrice (2001). "La bande dessinée japonaise pour filles et pour femmes". Neuvième Art (in French). Angoulême: Éditions de l'An 2 (6). ISSN 2108-6893.

- Suzuki, Kazuko (2015). "What Can We Learn from Japanese Professional BL Writers?: A Sociological Analysis of Yaoi/BL Terminology and Classifications". In McLelland, Mark; Nagaike, Kazumi; Katsuhiko, Suganuma; Welker, James (eds.). Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. pp. 93–118.

- Welker, James (2015a). "A Brief History of Shōnen'ai, Yaoi and Boys Love". In McLelland, Mark; Nagaike, Kazumi; Katsuhiko, Suganuma; Welker, James (eds.). Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. pp. 42–75.

- Shamoon, Deborah (2012). "The Revolution in 1970s Shōjo Manga". Passionate Friendship: The Aesthetics of Girl's Culture in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-82483-542-2.

- Tamura, Kaoru (2019). "When a Woman Betrays the Nation: an Analysis of Moto Hagio's The Heart of Thomas". Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. St. Louis: Washington University Open Scholarship.

- Taylor, Zoe (2006). "Girls' World : How the women of the 'Year Group 24' revolutionised girls' comics in Japan in the late 1970s". Varoom! The Illustration Report. London: Association of Illustrators (33): 34–43.

- Thorn, Rachel (2005). "The Moto Hagio Interview". The Comics Journal. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books (269): 138. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007.

- Toku, Masami (2004). "The Power of Girls' Comics: The Value and Contribution to Visual Culture and Society". Visual Culture Research in Art and Education. Chico: California State University, Chico.

- Welker, James (2006). "Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent: 'Boys' Love' as Girls' Love in Shôjo Manga". New Feminist Theories of Visual Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 31 (3): 841–870. doi:10.1086/498987.

- Reviews

- Berlatsky, Noah (January 2, 2013). "The Gay Teen-Boy Romance Comic Beloved by Women in Japan". The Atlantic. Washington: Emerson Collective. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- Brothers, David (January 4, 2013). "Moto Hagio's The Heart of Thomas Is A Dense, Heartfelt Read". Comics Alliance. New York. Archived from the original on September 3, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Randall, Bill (2003). "Three By Moto Hagio". The Comics Journal. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books (252). Archived from the original on May 14, 2003.

- Silverman, Rebecca (2013). "Review: The Heart of Thomas". Anime News Network. Canada. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Takamine, Haru (March 2, 2014). ""マンガとアニメとキリスト教" クリスチャンが選ぶサブカルチャー『トーマの心臓』". Christian Today (in Japanese). Tokyo: Christian Today Co., Ltd. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Thompson, Jason (2012). "Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga - The Heart of Thomas". Anime News Network. Canada. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Wakabayashi, Rio (October 15, 2020). "萩尾望都『トーマの心臓』が少女漫画界に与えた影響 "心の痛み"を描いた名作を再読". Real Sound (in Japanese). Tokyo: 株式会社blueprint. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- Welker, James (2015b). "Review of The Heart of Thomas". Mechademia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016.

External links

- The Heart of Thomas (manga) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- The Heart of Thomas theatrical adaptation at Studio Life