The Nabataean Agriculture

The Nabataean Agriculture (Arabic: كتاب الفلاحة النبطية, romanized: Kitāb al-Filāḥa al-Nabaṭiyya, lit. 'Book of the Nabataean Agriculture'), also written The Nabatean Agriculture, is a 10th-century text on agronomy by Ibn Wahshiyya, from Qussayn in present-day Iraq. It contains information on plants and agriculture, as well as magic and astrology. It was frequently cited by later Arabic writers on these topics.

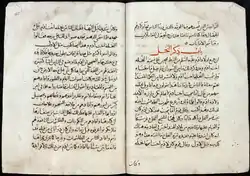

?14th century copy | |

| Author | Ibn Wahshiyya |

|---|---|

| Original title | الفلاحة النبطية |

| Country | Iraq |

| Language | Arabic |

| Subject | Agriculture, occult sciences |

The Nabataean Agriculture was the first book written in Arabic about agriculture, and the most influential. Ibn Wahshiyya claimed that he translated it from a 20,000-year-old Syriac text. Modern scholars believe either that he wrote the work himself or that he translated it from a Syraic original of the 5th century A.D. Several scholars have attempted to reconstruct the sources of the original text, and have traced its roots and traced its roots back Greek and Latin agricultural writings, heavily supplemented with local material.

The work consist of some 1500 manuscript pages, principally concerned with agriculture but also containing lengthy digressions on religion, philosophy, magic, astrology, and folklore. Some of the most valuable agricultural material is that about vineyards, arboriculture, irrigation and soil science. This agricultural information became well known throughout the Arab world from Yemen to Spain, and played a part in sparking the Andalusian Arab Agricultural Revolution.

The non-agricultural material paints a vivid picture of rural life in 10th century Iraq. It describes a pagan religion with connections to ancient Mesopotamian beliefs, tempered by Hellenistic influences. This religious material was discussed by Maimonides in his Guide for the Perplexed (c. 1190), and so passed into the European tradition. The Nabatean Agriculture also contains information about magic, which was transmitted to Europe through the Ghayat al-Hakim (Picatrix, 11th century).

Background

The term Nabataean refers to two different groups of people: the Arabs of the Nabataean Kingdom at Petra, and the Nabataeans of Iraq, who spoke Aramaic rather than Arabic.[1] The etymology of the word Nabataean is disputed, and the two groups were not related by descent.[2] The Nabataean Agriculture is about the Nabataeans of Iraq, who were believed by medieval Arabs to have been the indigenous inhabitants of Mesopotamia before the Islamic conquests.[3] They are closely associated, and sometimes identified with, other Mesopotamian peoples such as the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Chaldeans.[3] The Nabataeans of the 10th century were known as rural farmers[2] and peasants.[4] Written at a time when ancient Mesopotamian culture was in danger of disappearing due to the Arab conquests, Ibn Wahshiyya's work can be interpreted as part of the shu'ubiyya, a movement by non-Arab Muslims to reassert their local identities.[5] In this view it is an attempt to celebrate and preserve the heritage of Mesopotamia.[6]

The Nabataean Agriculture was the first book written in Arabic about agriculture,[7] although it was preceded by several books on botany and translations of foreign works on agriculture.

Composition

The work purports to have been compiled by a man named Ibn Wahshiyya from Qussayn, a village near Kufa in present-day Iraq. It includes a preface in which he gives an account of its origin.[lower-alpha 1] This preface states that Ibn Wahshiyya found the book in a collection of books from the Chaldeans, and that the original was a scroll with a thousand parchment sheets.[8] The original bore the lengthy title Kitab iflah al-ard wa-islah al-zar' wa 'l-shadjar wa 'l-thimar wa-daf' al-afat 'anha (Book of cultivation of the land, the care of cereals, vegetables and crops, and their protection), which Ibn Wahshiyya abbreviated to Book of the Nabataean Agriculture.[9] The original text was written in "al-suryaniyya al-qadima" ("ancient Syriac"), a dialect of Eastern Aramaic.[9] Ibn Wahshiyya translated the text to Arabic in 903/4 AD,[10] and then dictated the translation to his student Abu Talib al-Zayyat in 930/1 AD.[11] These dates are probably accurate, because Ibn al-Nadim lists the book in his Fihrist (Index) of 987, showing that the book was circulating in Iraq by the end of the 10th century.[12] However, it is not clear whether the book is actually based on a Syriac original or if it is a pseudotranslation, with the Syriac background invented by Ibn Wahshiyya.

Ibn Wahshiyya said that the book was the product of three "ancient wise Kasdanian[lower-alpha 2] men", of whom "one of them began it, the second added other things to that, and the third made it complete."[15] These three compilers were named Saghrith, Yanbushad, and Quthama.[9]

Modern scholars do not take Ibn Wahshiyya's claims at face value, and believe that the oldest parts of the work derive from late antique sources.[12] These must have included Arabic or Syriac translations of Greek and Latin books on agriculture, including the 4th-century writer Vindonius Anatolius.[16][12] However, reconstructing Ibn Wahshiyya's sources is difficult because he translated them loosely, added his own material and commentary, and used oral informants to supplement the written sources.[12] Angelo Carrara has proposed that the Nabataean Agriculture, as well as another book called the Geoponica, are based on a work which is now lost, the Rusticatio of Mago the Carthaginian, written sometime before the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC.[17] Aside from the agricultural sources, Ibn Wahshiyya must have had access to geographical information, because he discusses conditions in Tunisia, East Africa, Kashmir, Ceylon, and China.[18] The most likely source of this information is News of China and India (851) and a general geography text such as that of Ibn Khordadbeh.[18]

Contents

| Subject area | Percent of the work |

|---|---|

| Soils, fertilizers, irrigation | 5% |

| Arboriculture, fruit trees | 25% |

| Olive cultivation | 3% |

| Vineyards, wine | 16% |

| Field agriculture | 18% |

| Garden cultivation | 23% |

| Seasonal calendar | 7% |

| Weather almanac | 2% |

The book contains valuable information on agriculture and its associated lore. It is divided into chapters on "olive trees; hydrophantica; floral and odoriferous plants; trees and shrubs; a vade-mecum for the farmer; leguminosae and grass trees; edible plants; plant phytobiology / morphology; vegetables; vine; trees in general; a de causis plantarum; palm tree; [and] a summary of the material as a whole."[20] Amidst its extensive agricultural material the text also contains religious, folkloric, and philosophical content. The style is "repetitive" and "not always completely lucid,"[21] and the organization is "perplexing", even "baffling", as when a discourse about corpses washed out of a cemetery interrupts the section on soils.[22] At the same time, the author's attitude towards agriculture is "sober," and he appears as a "learned and perspicacious observer."[23]

Agriculture

Then I translated this book...after I had translated some other books...I gave a complete and unabridged translation of it because I liked it and I saw the great benefits in it and its usefulness in making the earth prosper, caring for the trees and making the orchards and fields thrive and also because of the discussions in it on the special properties of things, countries and times, as well as on the proper times of labors during the seasons, of the differences of the natures of [different] climates, on their wondrous effects, the grafting of trees, their planting and care, on repelling calamities from them, on making use of plants and herbs, on curing with them and keeping back maladies from the bodies of animals and repelling calamities from trees and plants with the help of each of the plants.[24]

The overall structure of the agricultural information in The Nabataean Agriculture does not match the agricultural context of Mesopotamia, suggesting that Ibn Wahshiyya modeled the work on texts from a Mediterranean environment.[25] For example, the work provides limited coverage of sugar, rice, and cotton, which were the most important local crops in the 9th and 10th centuries.[25] Sesame oil was more common in the region than olive oil, but Ibn Wahshiyya writes about the olive tree for 32 pages, compared to one page for sesame.[25] Nevertheless, the geographic references and detailed information about weather, planting schedules, soil salinity, and other topics show that Ibn Wahshiyya had firsthand knowledge of local conditions in the central Iraqi lowlands near Kufa.[18]

The book describes 106 plants, compared to 70 in the contemporary Geoponica, and offers thorough information on their taxonomic characteristics and medicinal uses.[26] The section on the cultivation of the date palm was an important contribution and wholly original, and the extremely detailed treatment of vineyards goes on for 141 pages.[25] The list of exotic plants, some of which are native only to India or Arabia, may have been based on the botany portions of Pliny's 1st-century Natural History.[27]

In soil science, The Nabataean Agriculture was more advanced than its Greek or Roman predecessors, analyzing the different soil types of the Mesopotamian plains (alluvial, natric, and saline), Syria (red clay), and the Zagros Mountains of northern Iraq.[25] It provided accurate and original recommendations on soil fertilizer.[25] In the area of hydrology and irrigation, the text offers "a treasure trove of information, ideas and subtle symbolism."[25] This includes material on how to dig and line wells and canals, and description of norias (water wheels).[25] Finally, there is a section on farm management, which shows evidence of Roman influence.[25] Overall, the agronomic contributions of The Nabataean Agriculture are "substantial and far-ranging, including both agronomic and natural history data unknown in the Classical literature."[22]

Religion and philosophy

For when we see plants, crops, running water, beautiful flowers, verdant spots and pleasing meadows, our souls are often delighted and pleased by this and are relieved and distracted from the sorrows that came to the souls and covered them, just as drinking wine makes one forget one's sorrows. As this is so, then when the vine climbs up the palm tree in such a soil as we have described before, looking at it is like looking at the higher world, and it acts on the souls in a similar manner as the Universal Soul acts on those particular souls that are in us.[28]

In various passages the book describes the religious practices of rural Iraq, where paganism persisted long after the Islamic conquest.[29] This religion was a branch of the Sabian religion, and was related to both the cult of Harran in northern Mesopotamia and Mandaeism in the Mesopotamian Marshes.[30] Some of Ibn Wahshiyya's descriptions suggests links between the Sabians and ancient Mesopotamian religion.[31] The cult was polytheistic, but all of the deities were subordinated to one supreme being.[32] Some of these deities were evil, as Ibn Wahshiyya makes clear in his story of an offering to Zuhal (Saturn).[33] Ibn Washiyya's description of the Tammuz ritual is particularly valuable, as it is more detailed than any other Arabic source.[33] In this ritual, people would weep for the god Tammuz, who was "killed time after time in horrible ways," during the month of the same name.[34][lower-alpha 3] Ibn Wahshiyya also explains that the Christians of the region had a very similar practice, the Feast of Saint George, and speculates that the Christians may have adapted their custom from the Tammuz ritual.[35]

The philosophical views of the author are similar to those of the Syrian Neoplatonist school founded by Iamblichus in the fourth century.[36] The author believed that through the practice of esoteric rituals, one could achieve communion with God.[36] However, the worldview of the text contains contradictions and reflects an author that is philosophically "semi-learned".[37] One of the key philosophical passages is a treatise on the soul, in the section on vineyards, in which the author expresses doctrines very similar to those of Neoplatonism.[38]

Magic

The magician 'Ankabutha even generated a man and he described in his book on generation how he generated him and what he did so that he could complete the being of that man. He did admit, though, that what he generated was not a complete example of the species of man and that it did not speak nor understand.[39]

Magic for Ibn Wahshiyya consisted of "invocations to astral deities, magical recipes and forms of action," and could be subdivided into white and black magic.[23] One Nabataean magician even succeeded in creating an artificial man, in a story similar to the golem traditions of Kabbalistic Judaism.[40] Other magical techniques are more suited for everyday use, such as the procedure for restoring a spring which is running dry: while the moon is waxing, one should either have a young man urinate into the spring three times, or place the horns of a bull into the bed of the stream, a cubit from the spring.[41]

Folklore and literature

They say, for example, that a farmer woke up on a moonlit night and started singing, accompanying himself on the lute. Then a big watermelon spoke to him: “You there, you and other cultivators of watermelons strive for the watermelons to be big and sweet and you tire yourselves in all different ways, yet it would be enough for you to play wind instruments and drums and sing in our midst. We are gladdened by this and we become cheerful so that our taste becomes sweet and no diseases infect us.”[42]

The author frequently digresses from the main theme to tell folkloric tales, saying that he includes these both to instruct the reader and for entertainment, because "otherwise fatigue would blind [the reader's] soul."[43] Many of the tales concern fantastical concepts such as talking trees or ghouls.[44] Others are about Biblical characters or ancient kings, although the names of the kings are not those of any known historical kings, and the Biblical characters are altered from their customary forms.[45] The tales are often related to agriculture, as when Adam teaches the Chaldeans to cultivate wheat, or King Dhanamluta plants so many water lilies in his castle that "the overabundance of water lilies around him, both their odour and their sight, caused a brain disease which proved fatal to him."[46] There are some references to poetry,[47] and fragments of debate poetry which are among the earliest in Arabic literature.[12] Debate poetry is a genre in which two natural opposites such as day and night dispute their respective virtues. The examples in the text include boasts by olive trees and palm trees, and are similar in style to the Persian Drakht-i Asurig, a debate between a goat and a palm tree.[48] At times, the stories conceal a hidden inner meaning, as in a text purporting that the eggplant will disappear for 3000 years. The author explains that this is a symbolic expression in which the 3000 years signify three months, during which eating eggplant would be unhealthy.[49]

Influence

The Nabataean Agriculture is the most influential book on agriculture in Arabic. It was the first agronomical work to reach Al-Andalus, and became an important reference for the writers of the Andalusi agricultural corpus. Ibn al-'Awwam in his Kitab al-filaha cited it over 540 times.[27] Others who cited him include Ibn Hajjaj, Abu l'Khayr, and Al-Tighnari, and he influenced Ibn Bassal.[50] The agricultural history of Yemen is not well known, but The Nabataean Agriculture must have reached Yemen by the era of the Rasulid dynasty,[51] as demonstrated by quotations in the work of Al-Malik al-Afdal al-'Abbas (d. 1376).[52]

The Nabataean Agriculture also had a far-reaching impact on the literature of the occult, through quotations in the Ghayat al-hakim (Goal of the wise man) of Pseudo-al-Majriti.[12] Ghayat al-hakim was later translated into Latin under the title Picatrix,[12] and influenced the development of Western esotericism.

In the 12th century Maimonides quoted The Nabataean Agriculture in his Guide for the Perplexed, as a source on Sabian religion.[53][54] Later translations of Maimonides into Latin mistranslated the name of the work as De agricultura Aegyptiorum (On Egyptian Agriculture), which caused readers such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Samuel Purchas to refer to the book by this erroneous title.[55] Ernest Renan claimed that Thomas Aquinas cited the book as well, in the 13th century.[56] In the 14th century, Ibn Khaldun mentioned the work in his Muqaddimah, although he believed that it had been translated from Greek.[36]

Traces of Ibn Wahshiyya's influence appear in Spanish literature as well. Alfonso X of Castile (1221–1284) commissioned a Spanish translation of an Arabic lapidary (book about gemstones) by someone named Abolays.[57] This lapidary cites The Nabataean Agriculture (calling it The Chaldaean Agriculture), and Abolays claims, like Ibn Wahshiyya, to have translated the lapidary from an ancient language ("Chaldaean").[57] In the 15th century, Enrique de Villena also knew of The Nabataean Agriculture and referenced it in his Tratado del aojamiento and Tratado de lepra.[57]

19th century

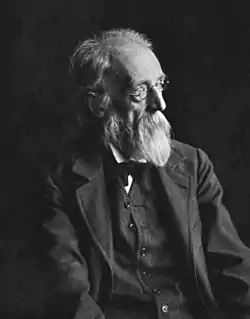

French scholar Étienne Quatremère first introduced the Nabataean Agriculture to European scholars in 1835.[11][58] Daniel Chwolson popularized it in his studies of 1856 and 1859, and believed that it provided authentic information about ancient Assyria and Babylonia.[59] He dated the original text to the 14th century BC at the latest.[36] However, his views provoked a "violent reaction" in the scholarly community, and a series of Orientalists set out to refute him.[36] The first of these was Ernest Renan in 1860, who dated the work to the 3rd or 4th century.[36] He was followed by Alfred von Gutschmid, who showed inconsistencies in the text and declared it a forgery of the Muslim era.[60][61] The eminent German scholar Theodor Nöldeke agreed with Gutschmid in an 1875 article and even argued that Ibn Wahshiyya himself was a fiction, and that the true author was Abu Talib al-Zayyat.[36][62] Nöldeke emphasized the Greek influences in the text, the author's knowledge of the calends (a feature of the Roman calendar), and his use of the solar calendar of Edessa and Harran rather than the Islamic lunar calendar.[36] The eventual decipherment of cuneiform showed conclusively that The Nabataean Agriculture was not based on an ancient Mesopotamian source.[63]

20th and 21st centuries

Interest in the book was slight for the first half of the 20th century.[63] Martin Plessner was one of the few Orientalists to devote attention to it, in 1928.[64][65] Toufic Fahd began studying the work in the late 1960s, and wrote many articles on it in which he defended the idea that the text was not a forgery by Ibn Wahshiyya, but was rather based on a pre-Islamic original.[66] Fuat Sezgin published a facsimile of the manuscript in 1984, and Fahd completed his critical edition of the text between 1993 and 1998.[66][67] Mohammad El-Faïz supported Fahd's views and studied the work from the standpoint of Mesopotamian agriculture, publishing a monograph on the subject in 1995.[68][69] Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila has been the main scholar of the work in the 21st century. In his The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture (2006), he critiques the work of Fahd and El-Faïz,[68] but concludes that the work was based on a Syriac original, probably from the 6th century.[70] The work has not been translated into a European language in full,[lower-alpha 4] but Fahd translated parts of it in to French in his articles, and Hämeen-Anttila translated other parts into English in The Last Pagans of Iraq.[72]

Editions

- Fahd, Toufic (ed.). L'Agriculture nabatéenne: Traduction en arabe attribuée à Abu Bakr Ahmad b. Ali al-Kasdani connue sous le nom d'lbn Wahshiyya. Damascus: al-Ma‘had al-‘Ilmī al-Faransī lil-Dirāsāt al-‘Arabīyah. (3 vols., 1993–1998.)

Notes

- Translated in Hämeen-Anttila 2002a, pp. 69–76.

- Chaldean; the usual Arabic word is al-Kaldani, but Ibn Wahshiyya uses the variants al-Kasdani and al-Kardani.[13][14]

- The practice is also mentioned in the Bible, Ezekiel 8:14: "Then he brought me to the door of the gate of the Lord's house which was toward the north; and, behold, there sat women weeping for Tammuz."[12]

- There may have been a medieval translation into Spanish, but it was lost after 1626.[71]

References

- Fahd & Graf 1993, pp. 834–835.

- Fahd & Graf 1993, p. 835.

- Fahd & Graf 1993, p. 836.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002a, pp. 61.

- Crone & Cook 1977, pp. 85–88.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002a, p. 64.

- al-Shihabi 1965.

- Carrara 2006, p. 124.

- Fahd & Graf 1993, p. 837.

- Carrara 2006, p. 123.

- Mattila 2007, p. 104.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2018.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002a, p. 66.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 16.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002a, p. 75.

- Rodgers 1980, p. 6–7.

- Carrara 2006, p. 131.

- Butzer 1994, p. 16.

- Butzer 1994, p. 19.

- Carrara 2006, p. 124–125.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002a, p. 71.

- Butzer 1994, p. 18.

- Hämeen-Anttila 1999, p. 44.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002a, p. 74.

- Butzer 1994, p. 17.

- Butzer 1994, pp. 16–17.

- Butzer 1994, p. 15.

- Mattila 2007, pp. 134–135.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002b, p. 89.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002b, p. 92.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002b, p. 93.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002b, p. 95.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002b, p. 96.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002b, p. 96, 98.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2002b, pp. 99–100.

- Fahd 1971.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 109.

- Mattila 2007, pp. 104, 134.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2003b, p. 40.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2003b, pp. 37–38.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 193.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 318.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 312.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, pp. 317, 324.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, pp. 312, 322.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, pp. 313, 315.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 316.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 318–320.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 92.

- Butzer 1994, pp. 25–26.

- Varisco 1997.

- Varisco 2011.

- Stroumsa 2001, p. 16.

- Ben Maimon 1956, pp. 315, 318, 334, 338 (part 3, chpts. 29, 37).

- Stroumsa 2001, p. 17.

- Renan 1862, p. 7.

- Darby 1941, p. 433.

- Quatremère 1835; See also the collected edition.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2003a, p. 41.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2003a, pp. 41–42.

- Gutschmid 1861.

- Nöldeke 1875.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2003a, p. 42.

- Fahd 1969, p. 84.

- Plessner 1928.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 8.

- Carrara 2006, p. 105.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 9.

- El-Faïz 1995.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 33.

- Hämeen-Anttila 2006, p. 333.

- Lahham.

Bibliography

- Ben Maimon, M. (1956). Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer (2nd ed.). New York: Dover Publishers. pp. 315, 318, 334, 338 (part 3, chpts. 29, 37). OCLC 1031721874.

- Butzer, Carl W. (1994). "The Islamic traditions of agroecology: crosscultural experience, ideas and innovations". Ecumene. 1 (1): 7–50. JSTOR 44251681.

- Carrara, Angelo Alves (2006). "Geoponica and Nabatean Agriculture : A new approach into their sources and authorship". Arabic Sciences and Philosophy. 16 (1): 103–132.

- Crone, Patricia; Cook, Michael (1977). Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-21133-8.

- Darby, George O. S. (1941). "Ibn Wahshiya in Mediaeval Spanish Literature". Isis. 33 (4): 433–438. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 330620.

- El-Faïz, Muhammad (1995). L’agronomie de la Mésopotamie Antique: Analyse du ‘Livre de l’Agriculture Nabatéenne’ de Qutama. Leiden: Brill.

- Fahd, T. (1969). "Retour a Ibn Waḥšiyya". Arabica. 16 (1): 83–88. ISSN 0570-5398. JSTOR 4055606.

- Fahd, Toufic (1971). "Ibn Waḥs̲h̲iyya". Encyclopaedia of Islam. III (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-08118-6. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- Fahd, Toufic; Graf, D. F. (1993). "Nabaṭ". Encyclopaedia of Islam. VII (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 834–838. ISBN 9004094199. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Gutschmid, Alfred von (1861). "Die Nabatäische Landwirtschaft und ihre Geschwister" [The Nabataean Agriculture and its siblings]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (in German). 15: 1–110.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (1999). "Ibn Wahshiyya and magic". Anaquel de Estudios Árabes (X): 39–48.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2002a). "Mesopotamian National Identity in Early Arabic Sources". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes. 91: 53–79. JSTOR 23863038.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2002b). "Continuity of Pagan Religious Traditions in Tenth-Century Iraq" (PDF). In Panaino, A.; Pettinato, G. (eds.). Ideologies as Intercultural Phenomena: Proceedings of the Third Annual Symposium of the Assyrian and Babylonian Intellectual Heritage Project. pp. 89–108.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2003a). "A Mesopotamian corpus: between enthusiasm and rebuttal". Studia Orientalia (97): 41–48.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2003b). "Artificial man and spontaneous generation in Ibn Waḥshiyya's al-Filāḥa an-Nabaṭiyya". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 153 (1): 37–49. JSTOR 43381251.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2006). The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Waḥshiyya and His Nabatean Agriculture.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2018). "Ibn Waḥshiyya". Encyclopaedia of Islam. 2019–1 (3rd ed.). Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789004386624. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- Lahham, Karim (ed.). "Ibn Waḥshīyah". Filaha Texts Project. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Mattila, Janne (2007). "Ibn Wahshiyya on the Soul: Neoplatonic Soul Doctrine and the Treatise on the Soul Contained in the Nabatean Agriculture". Studia Orientalia (101): 103–155.

- Nöldeke, Theodor (1875). "Noch Einiges über die 'nabatäische Landwirtschaft'" [Some more about the Nabataean Agriculture]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (in German). 29: 445–455.

- Plessner, Martin (1928). "Der Inhalt der Nabatäischen Landwirtschaft : Ein Versuch, Ibn Wahsija zu rehabilitieren" [The Content of Nabataean Agriculture: An Attempt to Rehabilitate Ibn Wahsija]. Zeitschrift für Semitistik und verwandte Gebiete (in German). 6: 27–56.

- Quatremère, E. M. (1835). "Mémoires sur les Nabatéens". Journal asiatique. 15: 5–55, 97–137, 209–71.

- Renan, Ernest (1862). An Essay on the Age and Antiquity of the Book of Nabathaean Agriculture. Trübuer.

- Rodgers, R. H. (1980). "Hail, Frost, and Pests in the Vineyard: Anatolius of Berytus as a Source for the Nabataean Agriculture". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 100 (1): 1–11. JSTOR 601382.

- al-Shihabi, Mustafa (1965). "Filāḥa". Encyclopaedia of Islam. II (2nd ed.). Brill Publishers. ISBN 90 04 07026 5. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Stroumsa, Guy G. (2001). "John Spencer and the Roots of Idolatry". History of Religions. 41 (1): 1–23. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 3176496.

- Varisco, Daniel Martin (1997). "Review of 'L'Agriculture nabateenne: Traduction en arabe attribuee a Abu Bakr Ahmad b. Ali al-Kasdani connu sous le nom d'lbn Wahsiyya'". The Journal of the American Oriental Society. 117 (2).

- Varisco, Daniel Martin (2011). "Medieval Agricultural Texts from Rasulid Yemen". Filaha Texts Project. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

Further reading

- Meyer, Ernst (1856). Geschichte der Botanik [History of Botany] (in German). III. pp. 43–89.

- El-Samarraie, H. Q. (1972). Agriculture in Iraq during the 3rd century, A.H. Beirut: Librarie du Liban.

- Sezgin, Fuat (1996). Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums, Band IV: Alchimie-Chemie, Botanik-Agrikultur. Bis ca. 430 He [History of Arabic Literature, Volume IV: Alchemy-Chemistry, Botany-Agriculture. Up to approx. 430 A.H.] (in German). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 318–29. ISBN 978-90-04-02009-2.

External links

- Digitized manuscript at the Berlin State Library, 1058

- Digitized manuscript at the Berlin State Library, 14th century

- Bodleian Library MS. Huntington 326 – facsimile of the ?14th century Arabic text