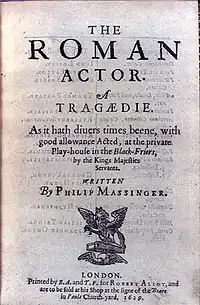

The Roman Actor

The Roman Actor is a Caroline era stage play, a tragedy written by Philip Massinger. It was first performed in 1626, and first published in 1629. A number of critics have agreed with its author, and judged it one of Massinger's best plays.[1][2]

Performance

The play was licensed for performance by Sir Henry Herbert, the Master of the Revels, on 11 October 1626, and performed later that year by the King's Men at the Blackfriars Theatre. Joseph Taylor, then the company's leading man, played the role of Paris, the title character. There is no record of another production of the play till 1692, when Thomas Betterton played Paris in a production by the United Company. The play was performed again in 1722 at Lincoln's Inn Fields. After that date the complete play fell out of fashion, though many actors, starting with John Philip Kemble in 1781, performed Paris's defense of the acting profession in Act I, scene 3 "as a short dramatic show-piece". Kemble also cut Massinger's text down to a two-act play that concentrated on Domitia's love for Paris; he staged this in 1781–82 and 1796.[3]

Publication

The play was first published in quarto in 1629 by the bookseller Robert Allot. Massinger dedicated the volume to three friends and supporters, Sir Philip Knyvett, "Knight and Baronet", Sir Thomas Jay and Thomas Bellingham "of Newtimber in Essex".[4] The commendatory poems that prefaced the play were written by John Ford, Thomas Goffe, Thomas May and Joseph Taylor.

Cast

The 1629 quarto also provides a list of the principal cast of the 1626 production:

| Role | Actor |

|---|---|

| Domitianus Caesar | John Lowin |

| Paris, the tragedian | Joseph Taylor |

| Parthenius, a freedman of Caesar's | Richard Sharpe |

| Aelius Lamia, and Stephanos | Thomas Pollard |

| Junius Rusticus | Robert Benfield |

| Aretinus Clemens, Caesar's spy | Eliard Swanston |

| Aesopus, a player | Richard Robinson |

| Philargus, a rich miser | Anthony Smith |

| Palphurius Sura, a senator | William Patrick |

| Latinus, a player | Curtis Greville |

| Domitia, the wife of Aelius Lamia | John Thompson |

| Domitilla, cousin-german to Caesar | John Honyman |

| Julia, Titus's daughter | William Trigg |

| Caenis, Vespasian's concubine | Alexander Gough |

In addition, James Horn and George Vernon played two lictors. (Several roles in the play are left off the list.) The 13-year-old John Honyman made his acting debut in this production; he played female roles for the King's Men for the next three years, to their production of Massinger's The Picture (1629); at the age of 17 he switched to young male roles.

Sources

Massinger based his portrait of the Roman Emperor Domitian on the work of Suetonius (most likely in Philemon Holland's 1606 translation), supplemented by works of Tacitus and Dio Cassius, plus the second Satire of Horace and Book XIV of Ovid's Metamorphoses, among other ancient sources. Ben Jonson's first Roman tragedy, Sejanus, was Massinger's model "in style and in structure" and for "scene outlines"; "the trial of Paris (I,3)...is written in close imitation of the trial of Cordus in Sejanus, Act III."[5]

Synopsis

The play opens with a conversation between Paris and two actors in his troupe, Latinus and Aesopus; they discuss the poor professional prospects they face. Their one great advantage is the patronage of the Roman Emperor Domitian; otherwise, the current atmosphere of political uncertainty leaves them with little audience; their "amphitheatre...Is quite forsaken". Two lictors appear to summon Paris to the Senate, where he must "answer / What shall be urg'd against you." As Paris and his actors leave with the lictors, they are watched by three senators, Aelius Lamia, Junius Rusticus and Palphurius Sura. The senators complain of the conditions under Domitian, and contrast the better times that prevailed under his predecessors, his father Vespasian and his brother Titus.

The play's second scene shows Domitia, the beautiful young wife of Aelius Lamia, being sexually solicited by Parthenius, a freed slave of Domitian. Parthenius wants her not for himself, but as Domitian's mistress; Domitia's resistance is less than vigorous. Aelius Lamia enters, and is outraged at what he finds; but Parthenius has a centurion and soldiers at his back, and forces the senator to agree to a divorce.

The third scene shows Paris defending himself before the Senate. Aretinus, a cynical informer, has accused Paris of libel and treason — he complains that the actors "traduce / Persons of rank" with "satirical, and bitter jests". Paris defends himself and his profession eloquently. (It is this material that was given a life of its own in later centuries, as discussed above.) The hearing breaks up without a conclusion when word arrives that Domitian has returned to Rome.

Domitian is shown to be a braggart and a cruel egomaniac. He confronts Aelius Lamia, who has dared to be offended over losing his wife, and executes him. Domitia quickly takes to the privilege and power of being Domitian's wife, to the distress of the other women in the imperial circle: Domitilla, Caesar's cousin and former lover; Julia, Caesar's niece and another former lover; and Caenis, the concubine of Vespasian.

Parthenius and the actors stage a short play to try to influence Parthenius's father Philargus; the old man is a rich miser who scrimps on his food and wardrobe to save money. The playlet is designed to show the old miser the error of his ways, by depicting a very similar figure. The strategy fails: Philargus sympathises with the stage miser and persists in his stubborn course. Domitian, as is his way, sentences the old man to death for his recalcitrance; Parthenius's plea for mercy is ignored. The playlet fails in its purpose — but Paris's performance captivates the attention of Domitia; she quickly becomes obsessed with the actor, and begins spending her time with him and his troupe.

The situation at court provokes resentment and conspiracy; the freedman Stephanos offers to assassinate the emperor for Julia and Domitilla. Parthenius earns Domitian's ire by suggesting caution in the treatment of two senators and friends of Lamia, Junius Rusticus and Palphurius Sura.[6] Domitian has had them arrested; the two men are tortured onstage, but their Stoic philosophy empowers them to resist the torture with equanimity. Domitian is shaken by their imperviousness to suffering.

Domitia's extravagant responses to Paris's acting reveals her emotional state to everyone except Domitian. Aretinus joins with the imperial women to inform Domitian of his wife's infatuation. They lead the emperor to spy on Domitia and Paris. Domitia uses both love and intimidation to try to seduce Paris; the actor resists at first, but equivocates to the point of kissing the empress. Domitian breaks in upon them, and has Domitia arrested; but he also orders Aretinus killed and the imperial women exiled, for showing him what he did not want to know.

Domitian confronts Paris alone; Paris humbly acknowledges his fault, and accepts his inevitable fate so sincerely that he almost seems able to talk his way out of his dire predicament. Domitian has Paris and his actors play a scene from a drama called The False Servant, that parallels their present situation; Domitian himself plays the injured husband. When the time comes for the emperor to play his part, he kills Paris, stabbing him with his real sword instead of the "foil, / The point and edge rebutted", that the actors use for their pretend fights. Domitian grants Paris a noble funeral.

Domitian sees the ghosts of the two Stoics Rusticus and Sura in his sleep; the figures wave bloody swords over their heads and remove a statue of Minerva, Domitian's divine patroness. When Domitian awakes, he finds the statue gone in fact. Thunder and lightning tell him that Jove has turned against him.

Resentment at Domitian's capricious tyranny grows; Parthenius and Stephano plan his assassination. An astrologer has predicted the emperor's death; Domitian executes the soothsayer, but surrounds himself with soldiers as he fearfully waits the time appointed for his death. Parthenius convinces Domitian that the appointed time has passed; the emperor dismisses his guards — and is stabbed to death by a crowd of his enemies, including Parthenius, Stephano, Domitilla, Julia, Caenis — and Domitia as well.

Modern productions

The Roman Actor received a noteworthy modern production in 2002, by the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Swan Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, directed by Sean Holmes. It was also revived as part of the 2010 Actors' Renaissance Season at the American Shakespeare Center in Staunton, Virginia.[7]

References

- Notes

- Logan and Smith, pp. 97–8.

- Gibson, p. xi.

- Gibson, p. 98.

- Knyvett (1583–1655) was created baronet in 1611; his daughter Dorothy Knyvett was the dedicatee of Massinger's poem The Virgin's Character. Jay (1585–1636) was a magistrate and member of Parliament, and also Keeper of the King's Armoury at Greenwich and the Tower of London. Bellingham (1599–1649) was the son of a Sussex knight. Gibson, p. 386.

- Gibson, p. 97.

- Massinger shows Rusticus and Sura as followers of Publius Clodius Thrasea Paetus — Massinger calls him Paetus Thrasea — a Stoic philosopher executed by Domitian. In historical fact, Thrasea was killed a generation earlier by Nero. Gibson, p. 120.

- "The Roman Actor | American Shakespeare Center". American Shakespeare Center. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Bibliography

- Garrett, Martin. Massinger: The Critical Heritage. London, Routledge, 1991.

- Gibson, Colin, ed. The Selected Plays of Philip Massinger. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Hartley, Andrew James. "Philip Massinger's The Roman Actor and the Semiotics of Censored Theater", Journal of English Literary History Vol. 68 No. 2 (Summer 2001), pp. 359–76.

- Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith, eds. The Later Jacobean and Caroline Dramatists: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama. Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1978.

- Reinheimer, David A. "The Roman Actor, Censorship, and Dramatic Autonomy". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, Vol. 38 No. 2 (Spring, 1998), pp. 317–32.