The Spring River Flows East

The Spring River Flows East, also translated as The Tears of Yangtze, is a 1947 epic Chinese film written and directed by Cai Chusheng and Zheng Junli and produced by the Kunlun Film Company. It is considered one of the most influential and extraordinary Chinese films ever made,[1] and China's equivalent of the Gone with the Wind.[2] Both films are based on the story of war and chaos, both of which have an epic style, and were considered classics in the film history of both China and the United States.[3] The Hong Kong Film Awards ranked it in its list of greatest Chinese-language films ever made at number 27.[4] It ran continuously in theatres for three months, and attracted 712,874 viewers during the period, setting a record in post World War II China.[5] The film features two of the biggest stars of the time: Bai Yang and Shangguan Yunzhu.[6]

| The Spring River Flows East | |

|---|---|

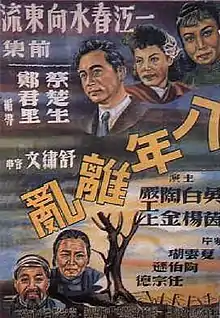

Poster for the first part of the film: Eight War-Torn Years | |

| Traditional | 一江春水向東流 |

| Simplified | 一江春水向东流 |

| Mandarin | Yī jiāng chūn shuǐ xiàng dōng liú |

| Directed by | Zheng Junli Cai Chusheng |

| Written by | Cai Chusheng Zheng Junli |

| Starring | Bai Yang Tao Jin Shu Xiuwen Shangguan Yunzhu |

| Music by | Zhang Zengfan |

Production company | Kunlun Film Company |

Release date | October 9,

|

Running time | 190 minutes |

| Country | China |

| Language | Mandarin |

The film is over three hours long and consists of two parts, Eight War-Torn Years (八年離亂) and The Dawn (天亮前後), released in separate dates in the same year, as it first premiered on October 9. It details the trials and tribulations of a family during and immediately after the Second Sino-Japanese War. Part One, Eight War-Torn Years tells the story of the early life and marriage of a young couple, Sufen (Bai Yang) and Zhang Zhongliang (Tao Jin) and the strain produced when the husband is forced to flee to Chungking, losing contact with the family he leaves behind in wartime Shanghai. Part Two describes Zhang Zhongliang's return to Shanghai after a second marriage into a wealthy bourgeois clan among whom by chance his impoverished first wife Sufen has found work as a maid.

Cast

- Bai Yang - Sufen

- Tao Jin - Zhang Zhongliang

- Shu Xiuwen - Wang Lizhen

- Shangguan Yunzhu - He Wenyuan

- Wu Yin - Zhang Zhongliang's mother

Plot

Part One: The Eight War-Torn Years

Part One is about 100 minutes in length.

The film is set in Shanghai and begins in the 1930s during the period of the Mukden Incident (1931–37) when the Japanese were occupying Manchuria. It is about a couple, Sufen (Bai Yang), a poor but honest young girl who works in a textile factory, and Zhang Zhongliang (Tao Jin), a teacher who gives evening classes to the factory workers. On National Day (October 10) the workers put on a show at the factory for their fellow workers, with Zhongliang acting as host. The vivacious Miss Wang Lizhen Shu Xiuwen, a relative of the factory manager, performs a Spanish dance to much applause. Zhongliang then gets up on the stage and makes a patriotic appeal to the workers to donate money to the Northeastern Volunteer Army who are resisting the Japanese invasion of northeast China. They throw money on the stage. Factory Manager Wen reprimands Zhongliang for inciting the workers, not because he objects to the sentiment, but because he fears it will get him into trouble with the Japanese.

Zhongliang falls in love with the shy and pretty Sufen and invites her to eat with him at his home, where he lives with his mother (Wu Yin). Later, as they embrace in the moonlight, Zhongliang tells Sufen, "You are the moon and I am your star". He puts a ring on her finger and swears he will see her in his mind every time he sees a full moon. They marry and have a son, whom they name Kangsheng ("to resist and to live on"). "Our generation will have to sacrifice so that he can have a better world," Zhongliang says. Meanwhile, as the Japanese approach Shanghai, the merchants evacuate their merchandise. Zhongliang tells Sufen and his mother that they should probably stay in Shanghai, but when things get too dangerous they should go to the country to work on his father and uncle's farm. Zhongliang gets a recommendation from the factory manager and joins the Red Cross, which sends him to the front to work in the medical corps. The well-connected Miss Wang Lizhen, the Spanish dancer at the entertainment, is going to Hankou to stay with the governor. As she leaves, she gives her card to Zhongliang, who is himself about to get onto the Red Cross truck. Manager Wen and his wife say they too have preferred to flee but plan to stay in Shanghai because the factory is still very profitable.

As the Japanese begin bombing Shanghai, Sufen, her mother-in-law, and the baby travel to the countryside to live in the family farm with Zhongliang's father and younger brother Zhongmin. This brother, Zhongmin, is a village schoolteacher by day and a fighter in the guerrilla resistance by night. Hearing that the Japanese are arresting the literate intelligentsia ("because they know right from wrong"), Zhongmin and three of his friends escape into the mountains.

The Japanese soldiers oppress the rural Chinese, requisitioning their rice and their cattle and forcing them, even the old and infirm like Zhonglianag's elderly father, to work in the rice fields. The starving villagers beg Zhongliang's father, a cultivated man, to use his wisdom and authority to try to convince the Japanese officers to reduce the rice levy so they will have something to eat and be able to work harder. When he does so, the Japanese accuse the old man of inciting the villagers to rebel and they hang him for his presumption, ordering that his body remain suspended, unburied, as a warning. That night the guerrilla fighters, led by Zhongmin, blow up the Japanese headquarters, killing the officers, and retrieve the father's body for burial. To avoid reprisals the guerrillas help the villagers escape to the mountains, but they send Sufen and her ailing mother-in-law and the baby, back to Shanghai by boat.

Meanwhile, the Japanese, disregarding the laws of war, have massacred Zhongliang's medical corps. Zhongliang only survives by feigning death. He later writes his family that he is in Hankou working as a teacher but makes no attempt to visit them. Two years later he is captured and made to do forced labor under terrible conditions, until a nighttime vision of his wife Sufen inspires him to make a successful escape. Zhongliang manages to reach Chungking, which is still under the control of the Chinese Nationalist government. Corruption there is rampant, however, and he is unable to find work of any kind: his past service against the Japanese counts for nothing. He sees a notice in the paper that Lizhen has been formally adopted as a goddaughter by the wealthy tycoon Pang Haogong. Destitute, in rags, and at the end of his rope, Zhongliang shows up at her door. Lizhen, who is living in luxury, takes him in and convinces her godfather to employ him in an office job at his company. However, Zhongliang soon discovers that his new colleagues are idlers who do nothing but drink and party. Demoralized, Zhongliang, formerly a teetotaler, takes to drink, and gradually he allows himself to be seduced by the dissolute Lizhen and thinks no more of his wife and son, thereby becoming a philanderer.

In Shanghai, Sufen now works during the day in a war refugee camp while taking care of her son and ailing mother-in-law in the evenings. Part One ends as a torrential thunderstorm pummels their shanty lodging.

Part Two: The Dawn

Part Two is about 92 minutes in length.

The film continues the saga of Zhongliang in Chungking, where, untouched by the war, business is booming. Lizhen uses her influence to have Zhongliang promoted to be Pang Haogong's private secretary. She also connives to get Pang Haogong to adopt Zhongliang, as well, which Pang Haogong says he might do if they marry. Zhongliang, though despairing, nevertheless has vowed to make something of himself. He is introduced into Pang Haogong's circle of wealthy industrialists, shows talent for wheeling and dealing, and soon makes his mark as an entrepreneur.

Back in Shanghai, the impoverished Sufen continues working and living among the refugees, supporting her mother-in-law and son, now a young boy, until the Japanese decide to dismantle the camp for military purposes. The soldiers force the refugees to live in an open field surrounded by barbed wire and allow them only starvation rations of rice. When one of the prisoners escapes, the others, many of them elderly women, are collectively punished by being made to stand all night in the waist-high, freezing waters of a canal.

In August 1945 the Japanese surrender. Zhongliang, believing his family to have died, has been adopted by Pang Haogong and has married Lizhen. He and his boss, Pang Haogong, fly back to Shanghai, leaving a reluctant Lizhen to follow them later. In Shanghai, the Nationalists have rounded up and imprisoned wartime collaborators, including Manager Wen. Zhongliang stays at the lavish home of one of Lizhen's family connections, her cousin, Wenyan (Shangguan Yunzhu). The two become lovers, to the scandal of the servants. Somewhat later Lizhen arrives from Chungking and there is tension between the two cousins.

Postwar conditions are tough. Sufen cannot afford to pay her rent or buy food, and she cannot contact her husband, whom she is sure will return, not realizing he has already been in Shanghai for two months. Their son, Kangsheng, is now nine years old and is working in the streets selling newspapers. To her mother-in-law's consternation, Sufen decides to find work as a maid, a job that her mother-in-law considers beneath people of their status, but it is that or starve. By coincidence Sufen finds work in Wenyan's household, though she is there for two days before she realizes that her husband is staying there also. The confrontation occurs when Sufen is sent to bring a tray of drinks at a National Day cocktail party. Sufen recognizes Zhongliang, as he is about to dance a tango with Lizhen. She collapses in shock, overturning the tray. Questioned by Lizhen, Sufen bursts out that Zhongliang is her husband and that they have been married for ten years and have a son. She recounts her years of suffering, bringing everyone to tears. Everyone except Lizhen and her cousin, who are mortified and accuse Sufen of purposely making them lose face in front of guests. Sufen runs out of the house, while Lizhen retreats to her room where she has a fainting fit Zhongliang runs to Lihen's side. He now cares only for his own social position and Lizhen's welfare, while Lizhen's cousin Wenyan privately gloats over Lizhen's comeuppance.

Sufen wanders desolately in the street all night and finally returns home. A letter has come from Zhongliang's younger brother Zhongmin, announcing his marriage to his childhood sweetheart. He has been fighting in the resistance all this time. They have ousted the governor of the province, and he is happy and teaching in the countryside. Kangsheng is happy and proud of his uncle and he announces he wants Uncle Zhougmin to be his teacher, too. The contrast with her own life is too much; Sufen collapses in sobs and bursts out that she has discovered that Zhongliang is back in Shanghai and is now married to another woman and has forgotten all about them. The grandmother insists on seeing her son right away, and the three of them go to confront Zhongliang at Wenyan's mansion.

When they do so, Lizhen, enraged, insists that Zhongliang divorce Sufen. He agrees. Mortified and totally disillusioned, Sufen runs out of the house with her son. They go to a quay, where Sufen asks her son to buy something for Granny to eat. When he comes back, a crowd has gathered, Sufen has drowned herself in the Huangpu River. She has left a note saying that Kangsheng is now a man and from now on he should strive to be like his uncle and not like his father. Kangshen goes to fetch his grandmother and both return to the pier to mourn Sufen. Zhongliang also arrives in a limousine with Lizhen. The grandmother, who seems to bear all the sorrows of China on her shoulders, berates her son, blaming him for Sufen's death. She brought him up to be a good, conscientious man, she says, but Sufen was more filial and took better care of her than he did. The grandmother lifts her eyes to heaven and asks when will be the end of this endless, endless suffering.

Title

The title derives from a poem composed by the last ruler of the Southern Tang dynasty, Li Yu (936/7 - 978). The poem, To the tune of ‘the Beauty Yu’ ("Beauty Yu" is the metaphoric name for Papaver rhoeas) was written shortly after the loss of his kingdom to the Song Dynasty. The “Beauty Yu” also is a “词牌” (Poem tune brand), ancient Chinese people used "Papaver rhoeas" to commemorate an unfortunate and beautiful wife of a military general"虞姬". The last sentence of this poem is the most famous and is also the name of this movie. It is often used to refer to the farewell with something and helpless feeling brought by the unfortunate fate.

How much sorrow can one man have to bear?

As much as a river of spring water flowing east.[7]

However, the sorrow in this film is not a man's sorrow as in this poem, but a woman's sorrow: it is Sufen, who has to experience loss, deprivation, exploitation, and mistreatment during and after the Sino-Japanese War. Such sorrow is especially highlighted in the second half of the film through the contrast between Sufen's struggling and Zhongliang's luxurious life.[8]

Historical background

From 1937 to 1945, the Sino-Japanese War heavily influenced the history of China. In this long-lasting warfare, the territories were occupied, and an estimated 20 million people died from it.[9]

During both the Second Sino–Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War, Sichuan was continuously under the administration of the Nationalist government. This makes it an ideal geographical focus for long-term observation of changes in the social effects of wartime mobilization during both periods.[10]

Theme

"May I ask how much sorrow you can carry? It feels like the Yangtze River flowing east endlessly downstream in the spring!" These two lines of lyrics open and are reprised throughout the epic film The Spring River Flows East. While spring usually represents a renewal of energy in a positive way, here it conveys a negative connotation, as the introductory lyrics indicate, that in springtime when the flow is strong, the river carries nothing but sorrow. Also, modernity and westernization are incorporated in the script to show the influx of foreign influences and changes of the time.[11]

In the final stage, the film is driven to the climax of sentiments, and it tries to tell the audiences that the fallen women are one of the fundamental causes of the tragic ending.[12]

In this film, the economic inequality in China is considered more as a moral issue, instead of as a societal issue.[13]

Zhang's infidelity is not so much an ethical aspect as a portrayal of the state of intellectual confusion, sway, escape, and transformation in the 1940s, so as to reflect the humanity and existence state of the intellectuals of this era in a deeper level.[14]

Political Influences

In August 1945, the Japanese surrendered, and within two years, the economy was in a disastrous state in need of recovery, while Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong fought for the political dominance of the nation that further plunged the country into anguish and chaos. In 1946, the nationalist state attempted to utilize the filming industry for ideologically control and manipulation through post-war films by instituting new film studios such as the Central Film Studio 1 and 2 (Zhongyang dianying sheying chang) on Huaying’s premises. In 1947, the socio-political campaign through filming was unsuccessful due to factionalism and mismanagement within the Nationalist organization, along with opposition, resistance, and criticism of the prejudiced policies from the Nationalists.[15]

Given the post-war economic state and the Nationalist’s ideological campaign, Spring River Flows East (Yi jiang chunshui xiang dong liu) surprisingly became the top box office film with its performance of cynicism with the Nationalist post-war disappointments. The post-war discussions in China were primarily about the complexity of political engagements and acts of treasons to the country as this discourse was defined by individuals who had lived through the war in the interior. Spring River Flows East is one of the most famous post-war films about the Japanese-occupied life through the narratives and perspectives of the suppressed who lived during the occupation.[15]

Production

By using montage techniques, the editing of this film builds up stark contrast, clearly showing the gender confrontation to the public.[12]

Both of the directors used to work as actors.[11]

Shooting a war scene on location would be too expensive, so the directors creatively used newsreel footage alongside footage shot on studio sets, finding ways through montage sequences highly influenced by Russian director Sergei Eisenstein, to re-create credible visuals within their minimalist budget.[11]

Re-release

During the Hundred Flowers Campaign, The Spring River Flows East was re-released China-wide in November 1956 and was again extremely popular. It was reported that people walked for miles in inclement weather to watch the film, and many were moved to tears. It provided a sharp contrast to the unpopular worker/peasant/soldier films made in the Communist era.[5]

Remake

The film was remade in 2005 as a television adaptation starring Hu Jun, Anita Yuen, Carina Lau, and Chen Daoming, but the newer version is translated into English as The River Flows Eastwards. An operatic adaptation by Hao Weiya under the title Yi Jiang Chunshui, with libretto by Luo Zhou and Yu Jiang, was premiered at the Shanghai Grand Theater in October 2014.[16]

References

- Zhou, Xuelin (1 September 2007). Young Rebels in Contemporary Chinese Cinema. Hong Kong University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-962-209-849-7.

- Clark, Paul (1987). Chinese Cinema: Culture and Politics Since 1949. CUP Archive. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-32638-4.

- 聂, 聂欣如 (2019). "中国影像程式:以《一江春水向东流》的视点为例[J]". 当代电影: 39–44.

- "Welcome to the 24th Hong Kong Film Awards". 24th Annual Hong Kong Film Awards. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- Wang, Z. (17 July 2014). Revolutionary Cycles in Chinese Cinema, 1951–1979. Palgrave Macmillan US. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-137-37874-3.

- "The Spring River Flows East". China.org.cn. 15 January 2003.

- "Oh When Will Autumn Moon and Spring Flowers End". Chinese-poems.com. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- Kemp, Philip (2017). "The Spring River Flows East". Sight & Sound. 27 (4): 103.

- Weigelin-Schwiedrzik, S., & Schäfer, C. (2014). The individual and the war: Re-remembering the sino-japanese war in the TV series A spring river flows east. (pp. 57-84) doi:10.1163/9789004277236_005

- Sasagawa, Yuji (2015). "Characteristics of and changes in wartime mobilization in China: A comparison of the Second Sino–Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War". Journal of Modern Chinese History: From the Second World War to the Cold War. 9: 66–94.

- Shin, Alice. "Seasons of pain and change: Tiff's 'a Century of Chinese Cinema'." CineAction, no. 91, 2013, p. 65+. Gale Literature Resource Center, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A346142607/LitRC?u=ubcolumbia&sid=LitRC&xid=422b5c90. Accessed 12 June 2020.

- Cui, Shuqin. Women Through the Lens: Gender and Nation in a Century of Chinese Cinema. University of Hawai'i Press, 2003. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqpfs. Accessed 14 June 2020.

- Paul, G. P. (2000). Victory as defeat: Postwar visualizations of china's war of resistance. () University of California Press. doi:10.1525/california/9780520219236.003.0011

- 周, 文姬 (2017). "40年代知识分子自我主体的剥离与建构——以《一江春水向东流》和《哀乐中年》为例[J]". 当代电影: 82–86.

- Fu, Poshek (2008). "Japanese Occupation, Shanghai Exiles, and Postwar Hong Kong Cinema". The China Quarterly. 194: 380–394. doi:10.1017/S030574100800043X.

- "China Shanghai International Arts Festival (in Chinese)". artsbird.com. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

External links

- The Spring River Flows East at IMDb

- Spring River Flows East, Part I at the Chinese Movie Database

- Spring River Flows East, Part II at the Chinese Movie Database

- Critical analysis from the La Trobe University

- Essay from China.org.cn

- Essay from ChinaCulture.org