Southern Tang

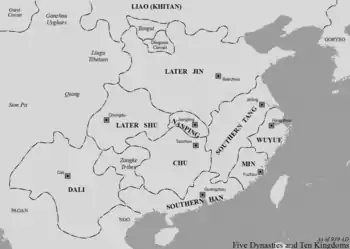

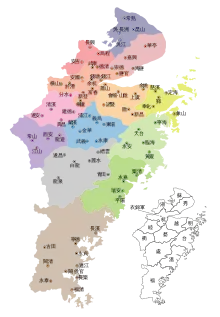

Southern Tang (Chinese: 南唐; pinyin: Nán Táng), later known as Jiangnan (江南), existed during Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in Southern China. The capital was located at Nanjing in present-day Jiangsu Province. At its territorial apex the Southern Tang controlled the whole of modern Jiangxi, and portions of Anhui, Fujian, Hubei, Hunan, and Jiangsu provinces.[3]

Great Qi / Great Tang / Jiangnan 大齊 / 大唐 / 江南 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 937–976 | |||||||||||||

Southern Tang in 939 AD | |||||||||||||

Southern Tang in 951 AD | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Jinling, Guangling[1] (briefly Nanchang)[2] | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Chinese | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Emperor/King | |||||||||||||

• 937–943 | Li Bian | ||||||||||||

• 943–961 | Li Jing | ||||||||||||

• 961–976 | Li Yu | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period | ||||||||||||

• Overthrow of Wu | 937 | ||||||||||||

• Renamed from "Qi" to "Tang" | 939 | ||||||||||||

• Became a vassal of Later Zhou as "Jiangnan" | 958 | ||||||||||||

• Became a vassal of the Song dynasty | 960 | ||||||||||||

• Annexed by the Song | 976 | ||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | China | ||||||||||||

The Southern Tang was founded by Li Bian in 937, when he overthrew emperor Yang Pu of Wu. He largely maintained peaceable relations with neighboring states. His son Li Jing didn't follow this foreign policy, conquering the Min Kingdom in 945 and Chu in 951.

The Later Zhou dynasty invaded the Southern Tang domain in 956 and defeated them by 958. Li Jing was forced to become a vassal of emperor Chai Rong, cede all territory north of the Yangtze River, and relinquish his title of emperor. In 960 the Southern Tang became vassals of the newly established Song dynasty. After Emperor Taizu had defeated the Later Shu and the Southern Han, he ordered the conquest of Jiangnan, which was completed in 975.

Background

Yang Xingmi was the Jiedushi of Huainan Circuit during the final years of the Tang dynasty. Throughout a series of conflicts with neighboring officials he expanded his control over most contemporary Jiangsu and Anhui, along with parts of Jiangxi and Hubei. In 902 Emperor Zhaozong recognized Yang Xingmi's conquests and granted him the title of the Prince of Wu (吳王). He ruled for three more years and died in 905. Yang Wo succeeded his father as the Prince of Wu.

In 907 the last Tang Emperor was evicted from power by Zhu Quanzhong, who declared the Later Liang dynasty. Yang Wo did not recognize this regime change as legitimate and continued to use the Tang era name of 'Tianyou'.[4] Without a reigning Tang emperor, however, he was in effect an independent ruler. In 921 Yang Longyan proclaimed his own reign title. His brother Yang Pu continued this trend of asserting ideological independence from the Kaifeng based regimes by claiming the title of Emperor in 927. This irrevocably ended diplomatic contact with the Later Tang.[4]

During a campaign in 895 an orphaned child was captured, whom Yang Xingmi initially took into his household. However, his oldest son Yang Wo disliked the child, and so Yang decided to give the child to his lieutenant Xu Wen. The child was given the name Xu Zhigao.[5] Using the threat of Wu-Yueh raids as an excuse, Xu Wen turned Chiang-nan into his base of operations.[6] This in time would morph into the Kingdom of Qi.[7] While Xu Wen assumed a position of power over the Yang family,[6] he likely didn't depose them due to unfavorable circumstances rather than the lack of will to do so.[8]

In 927 Xu Zhigao inherited Xu Wen's position of power behind the Wu monarchy and laid out the groundwork for his seizure of the throne.[6] He feared that the majority of the bureaucracy still supported the imperial Yang family.[4] The Crown Prince Yang Lian was arranged to marry one of his daughters.

In September 935 Yang Pu and Xu Zhigao settled on the territorial extent of the kingdom of Qi as having 10 of the 25 prefectures then under Wu control. [9] Yang Pu awarded Xu Zhigao the title of King of Qi (齊王) in March of 937. In May he dropped the ranking character 'zhi' from his given name to distinguish from his adopted brothers and was now known as Xu Gao. In October of the same year Yang Pu surrendered the state seal to him, ending Yang rule of Wu.

Foundation

On 11 November 937 Xu Gao ascended the throne of Great Qi (大齊). Xu Gao took inspiration from Tang governance and established two capitals.[4] Jingling was already his seat of power and became the principal location of the court. The old Wu capital of Guangling meanwhile maintained some significance as the secondary capital.[1] His reign according to Robert Krompart represented the initial rebuilding "of the social, economic, administrative, and religious forces that produce stability in China."[10]

Unlike the continual unrest and rebellions of the Central Plains, Tang rule across the Yangtze and Southern China had been generally more successful. These halcyon days became a source of nostalgia for locals in the south. This respect paid to the deposed dynasty became a useful political tool for Xu Gao.[11] Late in 936 the Later Tang were overthrown by combined Khitan-Chinese forces. This removed the only Chinese state claiming the name Tang, open the way for Xu Gao to claim it.[12] In February 939 Xu Gao renamed his realm to Great Tang (大唐).[4] Taking on the name of Tang increased Xu Gao's status. Such a move could be easily construed as to mean "the potential unification of [Chinese] territories under one ruler."[13]

On 12 March 939 Xu Gao took on the name of Li Bian. He additionally authorized a genealogy that claimed descent from the Tang Imperial family. Records vary about whom his supposed Tang progenitor was. Johannes L. Kurz concluded that the more reliable sources state his ancestor was either son or a younger brother of Xuanzong.[14] On 2 May 939 Li Bian performed the traditional sacrifices to Heaven. Jingnan and Wuyue sent ambassadors praising this event.[15]

The question of succession arose near the end of Li Bian's reign. He preferred his second son Li Jingda. However his oldest son Li Jing was eventually picked as his heir. In 943 Li Bian died and Li Jing succeeded his father.[16]

Economy

The Southern Tang and its neighbors were relatively prosperous compared to regimes successively in control of the Central Plains.[17] The greater agricultural productivity of Southern China created favorable conditions for local regimes. Consistent tax revenues were secured with the growing disposable income of the populous. Interstate trading of specialized crafts likewise was developed.[18][19]

Agricultural practices along the lower Yangtze River had underwent major modifications in the final years of the Tang dynasty. Intensive cultivation of rice was conducted in lowlands and adjacent reclaimed areas from waterways. Silk production developed into a regional cottage industry as farmers planted mulberry trees alongside their cereal crop. Meanwhile in nearby Piedmont areas agricultural oldest became specialized in growing tea or textile plants like hemp or ramie. By the time of the Southern Tang these practices were in efflorescence. Rice farmers had better yields and in general had more disposable income than their predecessors. This led to more state revenue by taxes on cereal and cash crops.[20]

In May 939 farmers that had cultivated 3,000 mulberry trees in the past three years were given fifty bolts of silk from Li Bian's treasury. Payment of 20,000 copper cash was awarded to those that reclaimed at least 80 mu (≈1,040 acres) of land. All new fields they cultivated were not taxed for 5 years. These measures have been credited with increasing agricultural production across the realm.[15]

Tributes were paid to the Later Zhou once they defeated the Southern Tang in 958. After the Song dynasty was established in 960 these payments became exorbitant. Tribute to the Song incurred a downturn of the Southern Tang economy.[21] After forcible incorporation into the Song Empire the former southern kingdoms became the focal point of the Chinese economy. Throughout their brief period of independence they had "laid the groundwork for the great economic surge that followed."[22]

Coinage

.jpg.webp)

Copper mining in the north was heavily disrupted by the constant warfare of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms era. In consequence bronze coins became scarce. The situation became dire in northern China. In 955 the Later Zhou Emperor Chai Rong banned the possession of bronze utensils upon pain of death.[23] The Southern Tang and their neighbors minted coinage from clay, iron, or lead. These coins for domestic circulation (despite having minimal value intrinsically) and to prevent the export of precious bronze coinage to neighboring states.[24][25]

Li Bian possibly cast a coin with the inscription Daqi Tongbao (大唐通寶) while the state still had its original name of Great Qi. During the reign of Li Jing cash coins were produced with the inscriptions Baoda Yuanbao (保大元寶), Yongtong Quanhuo (永通泉貨), Datang Tongbao (大唐通寶), and Tangguo Tongbao (唐國通寶). The latter two series were produced with the same inscriptions in different fonts of Chinese calligraphy while maintaining the same size and weight. Yongtong Quanhuo coins were initially valued at 10 copper coins. Counterfeits of these newly minted coins were circulated and led to distrust of them. Copper coins were still preferred by the populous, causing a rapid depreciation of the newer coins. Kaiyuan Tongbao (開元通寶) created during the Tang dynasty remained in circulation. Li Yu later minted coins with the same inscription in clerical and seal scripts.[26][27][28] [29]

The Southern Tang were the first in Chinese history to issue vault protector coins.[30] [31] These special coins served like numismatic charms and were hung in the treasury's spirit hall for offerings to the gods of the Chinese pantheon, and Vault Protector coins would be hung with red silk and tassels for the Chinese God of Wealth.[32]

Culture

The majority of Southern Tang court painters with surviving documentation were natives of Jiangnan. It is likely that the area had a potent artistic tradition before the formation of the Southern Tang. While most subjects were inherited, Southern Tang painters developed relatively new genres such as "landscape, ink bamboo, and flower-and-bird painting."[33] Additionally they developed artwork focused on marine life. Their Tang predecessors apparently didn't paint fish.[34]

The Hanlin Academy (翰林院) was founded in 943 and had large amounts of accomplished painters. There were only two other artistic academies in operation during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms era.[33] Those employed by the institution held hierarchical titles that denoted rank. The lowest ranked were likely apprentices to established artists. The Emperors of Southern Tang took part in the administration of the Hanlin Academy and oversaw the hiring of new painters.[35] Wu Daozi and Zhou Fang were among the stylistic standards for Southern Tang painters.[36] As successful artists took on apprenticeships the styles and genres popular with the Southern Tang court were likely transmitted to many artists outside the Hanlin Academy.[37]

In 975 the Song conquered the Southern Tang. Talented painters and poets were subsequently hired and brought to the Song capital.[38][39]

Foreign relations

Five Dynasties

The term "Five Dynasties" was coined by Song dynasty historians and reflects the view that the successive regimes based in Bian possessed the Mandate of Heaven.[40]

Compared to regimes of the Central Plains, the Southern Tang were economically prosperous. This created bottlenecks for any army advancing north as long supply trains were required. The Southern Tang military utilized a combination of infantry and naval forces, while calvary was seldom employed. However, in the open Central Plains calvary forces held the advantage. Peter A. Lorge concluded that these circumstances made Southern Tang campaigns into the Central Plains logisitically challenging.[41]

Hino Kaisaburō has detailed the principle routes used for inland economic and diplomatic exchanges between northern and southern Chinese states. These were the Grand Canal, Gan River, and Xiang River. Control of the Grand Canal was divided between several states, therefore it was the least used route in the era.[42]

In his foreign policy Li Bian has been described as maintaining a "martial conservatism." He recruited disaffected exiled officials from the north. The bountiful resources of the Southern Tang domain made some of the exiled officials push for an invasion of the Central Plains. Li Bian, however, apparently ruled without the desire to reunite the destroyed Tang Empire.[43] When pressed by his officials to invade the Later Jin and reunite the Tang Empire, Li refused to consider engaging in a conflict:

"As a child I grew up in the army and saw the profound damage soldiers did to the people. I cannot bear to hear words about this again. When I leave other people alone and in peace, then my people will be in peace as well. Why do you ask me to start a war then!"[44]

Later Jin

In 936 Shi Jingtang secured an alliance with the Yelü Deguang to overthrow his brother-in-law Li Congke of the Later Tang with Khitan forces. He ceded the Sixteen Prefectures, promised annual tribute, and accepted a subordinate role to Yelü Deguang. In return the Khitan ruler appointed Shi Jingtang as Emperor of the Later Jin. Throughout his reign Shi Jingtang maintained amicable relations with his overlord, despite criticism from many officials.{{sfn|Standen|2009|p=887}

In the summer of 938 Song Qiqiu proposed for the assassination of a Khitan dignitary that was visiting the Southern Tang court when they returned north through Later Jin territory. He felt that the murder could provoke a war between the Later Jin and the Khitans. While successful in killing the envoy, the harmonious relations between the Later Jin and Khitan continued.[45][46]

In 940 the Southern Tang supported backed a rebellion in the Later Jin territory Anyuan. Li Bian broke his policy of maintaining peaceable relations with neighboring states in a campaign that ultimately ended in Southern Tang failure. The military commissioner of Anyuan, Li Jinquan, contacted the Southern Tang with an offer to change allegiance from the Later Jin to the Southern Tang realm. Li Bian accepted the offer and sent an army northwards.[45]

Southern Tang forces met up with Li Jinquan as planned. But against Li Bian's commands its commanders ordered the looting Anlu. Afterwards, the Southern Tang army began to return home. Later Jin forces eventually caught up to the sluggish Southern Tang army and decisively defeated them in Mahuang Valley. The disobedience of his commanders upset Li Bian greatly. In a letter to Shi Jingtang, he claimed his generals were uncontrollable, as they were keen on career advancement through combat, and pressed for amicable relations. Thus ended Southern Tang pretensions to the Central Plains for the time being.[45]

Under the influence of Jing Yanguang, the second Later Jin Emperor Shi Chonggui pursued an antagonistic course with his overlord Yelü Deguang. This incensed the Khitan ruler who launched an invasion and defeated Shi Conggui in 946.[47]

Later Han

By 947 Liu Zhiyuan had evicted the Khitan forces and established the Later Han dynasty.

Based in modern Yuncheng, Shanxi, the Later Han military governor of Huguo Circuit (護國]), Li Shouzhen, revolted in the summer of 948. He sent envoys to Jinling in the hopes of securing an attack on the Later Han's southern flank.[48] Li Jing was amenable to an intervention and dispatched an army under Li Jinquan from the Huai River. This force reached modern Shandong, encamping across the Yi River from Linyi. One evening Later Han forces appeared and attempted to encircle the Southern Tang base. Li Jinquan was able to lead a retreat to the port of Haizhou with his forces intact. His inaction against the Later Han perturbed Li Jing that Li Lingquan never held another active military posting.[48]

After the ignominious withdrawal Li Jing contacted Liu Chengyou calling for the resumption of trade between the Southern Tang and Later Han. This request was denied and the two states continued to clash in border conflicts throughout 949.[48] In March an army of 10,000 was sent across the border into modern Anhui. Later Han rebel groups operating there were receptive to accepting Southern Tang rule. While stationed there a Southern Tang army captured Mengcheng. The Southern Tang commander hesitated when a Later Han army arrived and called for a retreat back to the Huai River.[48] Later that year another army was sent to seize territory across the Huai River. The campaign focused on Zhengyang, a city of strategic importance due to the ease of crossing the Huai River there. As in previous attempts of expanding north the Southern Tang army suffered a defeat from Later Han forces and retreated to the Huai River.[48]

Later Zhou

In March 951 the Later Zhou Emperor Guo Wei decreed in an edict to regulate contact with the Southern Tang:

"We have no hostile intentions towards the Tang. Both of us station troops along the Huai River, and both of us protect our border regions. We will not permit our troops and people to enter Tang territory illegally. Merchants can travel to and fro, and there will be no restrictions on trade."[49]

The Southern Tang were initially able to export their tea, salt, and silk without impediment to the Central Plains. Additionally the positive relations allowed the Southern Tang to pursue the conquest of Chu without Later Zhou interference.[49] This period of peaceable interactions quickly deteriorated as Guo Wei enforced his will over northern China.[50]

In 952 Li Jing sent assistance to Murong Yanchao, a member of the deposed Later Han imperial family that had revolted against the Later Zhou. The Southern Tang army reached Xiapi before Later Zhou resistance was met. Pushed south of Xuzhou, the Southern Tang lost a pitched battle and lost over 1,000 troops. Despite this failure, court officials pushed for conquering the Later Zhou. Han Xizai advised strongly against the idea as he felt Guo Wei was in a position of power. Li Jing ultimately concurred and ceased hostilities.[50]

Wang Pu composed a plan for the reunification of China. The memorial was sent to the Emperor Chai Rong in spring 955. The Southern Tang border was lengthy and likely would be hard for defending forces to keep Later Zhou armies out. This made them an ideal candidate for expanding Later Zhou power according to Wang Pu.[51]l}[52]

The Huai River became shallow during the winter and wasn't difficult to cross on foot. Southern Tang commanders annually posted troops along the river to protect against possible invasion. This practice was kept up until 955 when the commander of Shouzhou decided the practice was wasteful. Other officers in the area failed to convince Li Jing of how dangerous the lack of northern defenses was.[51]

Liu Yanzhen was appointed over 20,000 troops to defend against the invading Later Zhou, despite Song Qiqiu critiquing his inadequacies as a commander. At Zhengyang the Later Zhou constructed a floating bridge to cross the Huai River and invade Huainan.[53] Going against advice to maintain a defensive posture, Liu Yanzhen led an advance to Zhengyang. A Later Zhou force under Li Chongjin had recently crossed the bridge and moved to engage the incoming Southern Tang. The battle was a decisive rout for the Southern Tang as they lost 10,000 men and Liu Yanzhen himself was executed. The Later Zhou began to capture settlements south of the Huai River.[51]

On 2 March 956 Chai Rong arrived at Zhengyang and assumed personal command of the Later Zhou campaign. He ordered Shouchun to be encircled. A Southern Tang relief force 3,000 strong en route to Shouchun was defeated on 18 March about 10km from the besieged city.[51]

Li Jing hadn't prepared Yangzhou for a potential invasion by the Later Zhou as his defensive strategy depended upon armed positions along the Huai River. When Chai Rong learned of the unprepared state of Yangzhou he ordered a raid upon it. Several hundred Later Zhou calvary managed to infiltrate Yangzhou on 4 April without being detected by the city garrison. Surprised at the sudden appearance of enemy forces, the local commander set the city ablaze and retreated.[51]

Li Jing pleaded for peace and offered to become a Later Zhou vassal. On 1 April Chai Rong rebuffed Southern Tang envoys and Li Jing's proposal:

"He is separated from me by a river only, but has never sent envoys to establish good relations and instead only communicated with the Liao via the sea. Thus, he has abandoned China and served the barbarians."[54]

Several more peace feelers were sent throughout the spring. Six prefectures were offered to be ceded to the Later Zhou. This wasn't an appealing proposal to Chai Rong as his forces had already occupied sizable territories south of the Huai River.[55][56]

Li Jingda was appointed to command the entire Southern Tang military. Despite criticism of their paltry performances as commanders by Han Xizai,[55] Bian Hao and Chen Jue were selected as his subordinates. Over 10,000 Southern Tang troops were dispatched and briefly reclaimed Yangzhou. Li Jingda meanwhile established a defensive position with 20,000 men around 50km west of Yangzhou. This force was ten times larger than the Later Zhou armies in the area. In an ensuing battle the Later Zhou calvary crushed their opponents. Over half of Li Jingda's army was killed, destroying much of the Southern Tang pool of veteran troops.[55]

Chai Rong departed for Bian on 17 June and left his armies under the command of Li Chongjin. The Southern Tang made minor gains against the Later Zhou in his absence. Rather than push an offensive, Li Jing took the advice of Song Qiqiu and ordered his commanders to remain on the defensive and not attack Later Zhou positions. After the embarrassing string of defeats in the campaign Li Jing likely doubted the abilities of his remaining officers.[55] Shouchun meanwhile remained under siege by the Later Zhou. Southern Tang forces under Li Jingda were concentrated at Haozhou, roughly 90km away from the embattled city. A relief force was sent and reached Purple Mountain where they erected defensive structures. Li Chongjin led an attack on the stockades and killed around 5,000 Southern Tang troops.[57]

Li Gu advised Chai Rong to assume control of the siege of Shouchun once more to bolster the morale of his troops. The city was also close to surrender. Returning south in April, on the 9th Chai Rong successfully attacked the Southern Tang positions at Purple Mountain. About 40,000 Southern Tang were killed and several of their generals were captured. The beleaguered garrison of Shouchun surrendered to the Later Zhou on 23 April. Southern Tang control over Huainan was firmly removed.[57]

Throughout the winter of 957 Later Zhou forces captured a number of Southern Tang cities as they marched southwards, even gaining a direct land connection to their Wuyue vassal. In April 958 Li Jing sent out envoys again seeking peace with Chai Rong. The Southern Tang offered to cede all territory north of the Yangtze to the Later Zhou and become a vassal.[58] These terms were acceptable to Chai Rong. The state once called Great Tang (大唐) was rebranded the less grandiose Jiangnan (江南). Li Jing renounced the title of emperor and assumed the title of King of Jiangnan.[59] The Later Zhou calendar and reign title were additionally adopted by the court of Jiangnan. The Later Zhou gained control over almost a quarter million families.[57]

Ten Kingdoms

Leadership across the Ten Kingdoms didn't see a politically unified China under a centralized bureaucracy as necessarily inevitable.[60] Their sovereignty was revoked only through force of arms.[61] Conceptually there could only be one Son of Heaven but regional autonomy was still possible. Some kingdoms nominally accepted the suzerianity of the Five Dynasties. Several rulers simultaneously claimed to be emperors and still engaged in diplomatic exchanges with each other despite this breach of imperial orthodoxy.[62]

Li Bian dispatched ambassadors to the neighboring states of Jingnan, Min, Southern Han, and Wuyue on 21 November 937 to announce his assumption of the throne. By spring of the following year all four states had sent their own envoys to congratulate Li Bian on becoming emperor. Thus began interactions between the Southern Tang and their neighboring and often competing states.[13]

Min

Wang Yanxi sent Zhu Wenjin in 938 to represent the Min court and praised Li Bian for his assumption of the throne.[13] In January 940 Min representatives renewed arrangements previously made with the Southern Tang.[63] Later that year Wang Yanzheng revolted against his brother Wang Yanxi. Li Bian mediated between the feuding Wang Brothers. He was motivated to end the conflict quickly lest Wuyue take advantage of the civil war to seize territories in Fujian near the Southern Tang borders.[64][63] This peace didn't last long and the small state was torn apart from further civil war between the siblings in 943.[65] Wang Yanzheng seized the northwest regions of Min and formed the Kingdom of Yin. Li Jing initially pressed for the brothers to stop feuding as his father had done previously. Yet both of them refused this attempt at mediation. L Wang Yanzheng sent a particularly provocative response. Consequently, Li Jing ordered for Yin and Min territories to be forcibly incorporated into his realm.[66]

In April 944 Lian Chongyu and Zhu Wenjin dethroned Wang Yanxi of Min. Zhu Wenjin emissaries to try to establish friendly relations with the Southern Tang. Li Jing put his emissaries under arrest and intended to attack him, but could not do so immediately due to the heat and spread of disease at the time.[5] Min officials executed Zhu and Lian in February 945. The throne was offered to Wang Yanzheng, reuniting the split kingdoms. At this point the Southern Tang invasion was imminent. Wang Yangzheng continued to rule from Jianzhou rather than Fu and prepared his forces for the coming attack.[66]

Southern Tang armies defeated a major Min army at . Thereafter Jianzhou was put under siege. Min reinforcements from Quanzhou were defeated outside Jianzhou. Desperate for help, Wang Yanzhen offered to become a vassal of Wuyue in return for military assistance.[66] Nonetheless, on 2 October 945 Jianzhou fell and Wang Yangzheng was captured. Min officers still active at Quanzhou, Tingzhou, and Zhangzhou now surrendered. The majority of Min territory was now under Southern Tang rule.[66]

The final holdout of the Min Kingdom was the affluent port of Fu. It was a prosperous entrepôt that imported valuable goods originating from across South East Asia. Control of this trade "would have greatly added to the income of the Southern Tang treasuries."[67] While Li Jing was content to leave the city alone, his generals pressed for launching a siege from Jianzhou. Without authorization from the throne Chen Jue organized an army in 946 to attack Fu and appointed Feng Yanlu as its commander. Chen Jue then sent a memorial to the Imperial Court that claimed Fu could fall after a single day of siege. Li Jing was furious at this flagrant insubordination but rather than punish Chen Jue he sent reinforcements on the advice of Feng Yanji.[67]

The ruler of Fu, Li Renda, was desperate for outside support and became the vassal of Later Jin. In October 946 the Later Jin awarded him several titles but sent no military forces to end the siege of Fu. Some of the Southern Tang forces were tied down in a revolt in nearby Zhang Prefecture by Lin Zanyao. These rebels were defeated by Liu Congxiao in November. Fu became encircled by the Southern Tang.[67]

The nearby Wuyue Kingdom was also contacted for military aid. Qian Zuo accepted Li Renda's appeals. During winter 946 Wuyue forces arrived on naval transports to protect their new vassal. More reinforcements sailed in early 947. Feng Yanlu, the Southern Tang Commander, was keen to fight a pitched battle for prestige and material rewards. He allowed the additional Wuyue forces to disembark unopposed. This was a grave mistake as the Southern Tang army now faced opposing forces on two fronts. A coordinated attack by the Fu garrison and the Wuyue army struck. The Southern Tang were routed and Feng Yanlu perished alongside around 20,000 troops. The siege was lifted and the war soon came to a close. The conflict had incurred many expenses and for the Southern Tang and drained their treasury.[67]

Wuyue

The rulers of Wuyue maintained a status of vassal to the Northern dynasties.[43][65] This policy generally protected them against Southern Tang aggression. If attacked, their northern suzerians could strike at Southern Tang territories along the Huai River. This kept the Southern Tang and Wuyue in a state of equilibrium. In January 941 emissaries presented gifts from Wuyue to celebrate Li Bian's birthday.[63]

In August 941 the Wuyue capital of Hangzhou was devastated by fires. The ensuing chaos greatly distressed Qian Yuanguan, who died soon afterwards. Southern Tang military officers pushed for an invasion to seize Wuyue. Li Bian demurred to the idea: "How can I take advantage of the calamity of other people?"[68] Instead an army Li Bian sent out foodstuffs for the beleaguered people of Hangzhou. An opportune time to strike at a major rival of the Southern Tang was therefore passed over.[68]

Late in 946 the Wuyue became entangled in the Southern Tang conquest of Min. Li Renda had offered to become a Wuyue vassal return for military support against the Southern Tang forces laying siege to the port of Fu. The Wuyue government was divided about supporting an expedition. Qian Zuo was supported by only one court enunch supported to intervene in the conflict. Against the counsel of the military in December 946 he dispatched a 30,000 man force on naval transports to support Fu. At the beginning of 947 additional Wuyue reinforcements arrived. After defeating the Southern Tang army Li Renda contemplated resubmitting to Li Jing but was murdered by Wuyue general Bao Xiurang. Fu joined the Wuyue domain as a vassal.[67]

Southern Tang officers stationed at Jianzhou were given false information in March 950 of the Wuyue garrison departing from Fu. An army sent to capture the supposedly vacant city instead found it well defended. The Wuyue garrison general then lured the adversarial army in falling for a trap and inflicted heavy losses. Surviving remnants of the Southern Tang fled back to Jianzhou.[69]

The Wuyue participated in campaigns against the Southern Tang led by the Later Zhou and later the Song. In 956 Changzhou was put under siege, but the Wuyue army suffered heavy losses against a Southern Tang relief force.[70] Later, during the Song conquest of Southern Tang, the Wuyue seized Changzhou and Runzhou. Their forces joined the Song siege of Jinling.[71]

Chu

A succession crisis erupted in Chu after the death of Ma Xifan. His designated heir was Ma Xiguang while Ma Xi'e was preferred by Chu court officials. Ma Xi'e revolted in 949 and raised an army. He requested his claim to the Chu throne be recognized by the Later Han but Emperor Liu Chengyou refused. Undeterred, Ma Xi'e pledged vassalage to Li Jing for military backing against his brother. In January 951 the forces of Ma Xiguang were routed and Ma Xi'e took over the Chu capital of Tanzhou.[72]

As the new King of Chu, Ma Xi'e sent tribute to the Southern Tang court. His envoy treacherously discussed the overthrow of the ruling Ma family with Li Jing. Dissatisfied military officers deposed Ma Xi'e and enthroned Ma Xichong. His rule was far from certain and he feared his generals. Ma Xichong requested aid from Li Jing,[65] who immediately dispatched Bian Hao and a 10,000 strong force from Yuanzhou. Arriving at Tanzhou in November, they were welcomed by Ma Xichong.[49]

Bian Hao quickly deposed Ma Xichong and in December both Ma Xichong and Ma Xi'e were ordered by Bian Hao to travel to Jinling. Once there Li Jing didn't allow for either to return to Hunan. Instead, they received appointments in the Southern Tang bureaucracy. The majority of Chu territory was now in Southern Tang possession. Li Jianxun warned that "this is where misfortune starts!"[73] The Southern Tang managed the former Chu lands "not as a new part of their empire, but as a defeated state."[74]

Liu Sheng of the Southern Han also ambitions of gaining Chu territory. In the winter of 951 he launched a successful invasion to secure Lingnan. Subsequently a Southern Han army advanced to capture Chenzhou. Bian requested that prefects be commissioned at Quan (全州) and Dao (道州) to defend against future attacks by the Southern Han. An attack by the Southern Tang to reclaim Juzhou ended in complete failure after an ambush by the Southern Han.[75]

Trouble would soon brew in Tanzhou itself as well. After Bian's takeover, much of the treasures and stored wealth of Chu were delivered to Jinling. The expenses of the occupying army were covered by additional taxes on the people of Hunan. Rations and payments to local troops, many formerly Chu, were decreased. A conspiracy to kill Bian and then submit to Later Zhou was formed by disenchanted soldiers. When they revolted in spring 952, however, Bian realized what was occurring and successfully defended against the attack. Later in the year a petition presented to Li Jing pointed out that Bian was indecisive, incompetent, and unable to rein in his subordinates. It was argued that Bian needed to be replaced or the former Chu realm would be lost. Li took no heed.[5]

From his base in Langzhou Liu Yan gathered a coalition of former Chu troops. He was nominally a Southern Tang vassal but when summoned to Jinling he refused. Expecting a retaliatory attack from the Southern Tang, Liu Yan launched a preemptive strike to capture Tanzhou. The Southern Tang positions along the way quickly collapsed. Yuanjiang fell to the invaders on 26 October. After briefly defending Tanzhou, Bian decided to abandon the city on 1 November. Yeuzhou fell shortly afterwards. Without control of either city the Southern Tang administration of Hunan crumbled. Liu Yan now had control over the majority of the former Chu domain. He submitted to the Later Zhou in order to protect against a potentially revanchest Southern Tang.[76] Thus Li Jing's effort to control Hunan ended in an embarrassing rout.[77][78]

Southern Han

The Southern Han sent envoys in 940 to reconfirm agreements made with Southern Tang. In 941 the Southern Han proposed for the partition of the Chu realm. However Li Bian was unwilling to commit to the enterprise.[64] [68] The same year they sent gifts to celebrate Li Bian's birthday.[44]

Taking advantage of the Southern Tang invasion of Chu, in winter 951 Liu Sheng launched a successful invasion to secure Lingnan. The Southern Tang counterattack ended in failure and the Southern Han secured their territorial gains.[75]

Liao dynasty

The Khitan were an important partner for the Southern Tang. Both regimes used the other as a military counter to the Five Dynasties.[79] Dialog and gift exchanges were frequent during Li Bian's rule. He sent ambassadors to the Khitan court at Shangjing to announce the start of his reign. In correspondence Yelü Deguang and Li Bian referred to each other as brothers. This demonstrated the favorable opinion the Khitan held of the southern state compared to the reigning Later Tang.[80]

In 938 both Yelü Deguang and his brother Yelü Lihu dispatched gifts to Li Bian. Later that year a group of Khitan envoys visited with an impressive herd of 35,000 sheep and 300 horses.[81] In return for the livestock the Khitan received medicinal supplies, silk, and tea.[82] The Southern Tang court financed a piece called "Two Qidan Bringing Tribute" by an unnamed artist in honor of these proceedings. The painting symbolized the importance put on relations with the Khitan by Li Bian.[83]

Contact between the two states was blocked by the Central Plains regimes. Consequently a naval route was developed. Starting at Chunzhou Southern Tang ships sailed north along the coastline until the Shandong Peninsula, where ships crossed the Yellow Sea and landed at the Liaodong Peninsula.[84] The Khitans sent six diplomatic missions to the Southern Tang between 938 and 943. In 940 Khitan envoys presented Li a snow-fox fur robe. In both 941 and 942 the Southern Tang sent three diplomatic missions to the Khitans.[44]

After being insulted by an antagonistic Shi Chonggui, Yelü Deguang destroyed the Later Jin in 946. In early 947 he founded the Liao dynasty after entering Bian. Li Jing praised Yelü Deguang for dethroning the Later Jin and petitioned him to allow the Southern Tang to repair the dilapidated Imperial Tang tombs of Chang'an. The request was denied and greatly infuriated Li Jing who then ordered meetings to formulate an invasion of the Central Plains.[85] Yet the Southern Tang weren't in a position to launch an invasion north. Their forces were already embroiled in a war of conquest against Min.

Despite the motions made by the Khitan in founding an imperial dynasty, they treated the conquest as a "very large scale raid." Yelü Deguang soon departed for the Khitan homeland, dying on the way.[86][87] By the closing of the Min campaign in 947 Liu Zhiyuan had evicted the Khitan and founded the Later Han dynasty. The opportunity to move against the north had been missed by the Southern Tang.[88]

Efforts by the Southern Tang to secure an alliance with the Liao against the northern dynasties continued to flounder. In 948 Liao and Southern Tang officials formulated a joint attack against the Later Han. Yet the Liao delayed for over a year. Once they did attack the Later Han, Khitan forces only raided Hebei.[89][87]

When Muzong took the Liao throne, securing aid became more difficult for the Southern Tang. He was far less interested in participating in Chinese affairs than his predecessors.[90] [80] In 955 the Later Zhou began a campaign to subdue the Southern Tang. Li Jing requested military intervention by Muzong. His brother-in-law was sent to Tanzhou as an envoy to the Southern Tang in 959. The Liao were treated to a sumptuous feast by their Southern Tang hosts. Spies loyal to the Later Zhou were among those present. Muzong's brother-in-law was beheaded by the Later Zhou spies.[91] The Liao court was unaware that the Later Zhou perpetrated the murder. Muzong furiously revoked all contact with Li Jing, ending Liao-Southern Tang relations.[2][92][80]

Goryeo

In 936 Taejo united the Korean Peninsula under Goryeo. The newly formed state bordered the Khitans. The Later Jin reigned as a Khitan vassal which made them undesirable to the Koreans.[93] The strategic position of Goryeo was likely valued by the Southern Tang as a means to threaten the Khitan. Taejo sent a tribute mission to the Southern Tang in the summer of 938. A variety of locally produced goods were presented to Li Bian. Another mission from the Korean Peninsula arrived at Jinling in 938. The group was likely private traders from the recently conquered Silla.[94] A later mission from Goryeo brought more goods as tribute in 940.[93]

Decline

By the close of Li Jing's reign the Southern Tang was well on the way to obscurity. He had pursued a number of foreign adventures managed by incompetent military officers that generally ended in costly disaster.[95] From 955 to 988 the Later Zhou successfully campaigned against the Southern Tang. Li Jing was forced to cede all prefectures north of the Yangtze River and become a Later Zhou tributary. The realm became territorially truncated and lost the economic and political relevance it enjoyed when Li Jing assumed the throne 15 years earlier.

In February 960 Zhao Kuangyin deposed Guo Zongxun and established the Song dynasty as Emperor Taizu. Li Jing quickly sent envoys to confirm his loyalty and vassalage to Taizu.[95][92] Taizu pursued an expansionist agenda to unite China under his rule. Jiangnan wasn't a tactical priority compared to other states and was left alone in return for considerable tribute. In August 961 Li Jing died and his son Li Yu took over.[95]

Li Yu kept a semi-independent status as the Ruler of the State of Jiangnan (Jiangnan guozhu 江南國主). This came at a steep price of consistent tribute of gold, silver, and silk. Jiangnan was significantly smaller than the Southern Tang territorial apex achieved in the 950s. This made the large quotas demanded by the Song challenging to meet.[96] In 964 the Song decreed new economic regulations that made the situation even more dire. Northern merchants were forbidden travel into Jiangnan. New commodity taxes were imposed in Jiangnan that could only be paid in gold or silver.[97]

The Later Shu were crushed in 965 by Taizu. In 971 the Southern Han were likewise conquered by the Song. Taizu now turned his attention to Jiangnan.[98][99][100] Throughout 973 and 974 Li Yu was repeatedly summoned to the Song court. He feigned illness and claimed to be unable to make the trip. Tired of these excuses, Taizu raised an invasion force under the command of Cao Bin to extinguish Jiangnan.

The campaign began in November 974 and proceeded favorably for the Song. The Yangtze River was overcome with a floating bridge built across from Caishiji. Song forces crossed the waterway and secured a bridgehead. Outside Caishiji an army of 20,000 Jiangnan troops was defeated by Cao Bin.[101] Song forces continued to advance and reached the outskirts of Jinling in March 975. No defensive preparations were made by Li Yu. Both he and his court officials foolishly felt existing fortifications were adequate enough to keep the Song at bay. Starting in April the capital was put under siege by Cao Bin.[102]

In January 976 Li Yu surrendered outside his palace. He and his remaining courtiers kneeled down at the feet of Cao Bin. The deposed ruler reached Bian in February. The imperial portrait of Li Bian produced by Zhou Wenju was presented to Taizu. This measure signified the complete submission of Jiangnan to the Song.[37] Jiangnan was formally annexed and dissolved by the Song. The newly incorporated territories had 650,565 registered families. In 978 Li Yu died probably from actual illness, rather than being poisoned on the command of Taizu as some accounts claim.[103]

Historiography

Historical texts about the Southern Tang produced during the early Song were named after the Jiangnan region. By not using the formal name of the state authors denied "it the status of an independent state." Reign titles of the Southern Tang rulers were likewise seen as unacceptable and their personal names were used exclusively.[104]

The Jiu Wudai Shi is the earliest work of Song histograms to deal with the Southern Tang. The Five Dynasties were presented as passing on the mandate of heaven in a linear fashion to the succeeding dynasty. The Song were at the end of this process, gaining the mandate from the Later Zhou. This logic, which didn't factor the Southern Tang or other states, was critical to Song claims of legitimacy.[105] Other states of the period like the were seen not in possession of the mandate and therefore entirely illegitimate.Template:Cho-ying

The Southern Tang was denounced as a state of "usurpation and thievery" or jianqie (僭竊) in the Jiu Wudai Shi. Rulers were generally referred to using the word 偽 to label them as swindlers.Template:Cho-ying Despite these ideological attacks, the work accurately recorded political events between the Central Plain dynasties and the Southern Tang.[106]

Xu Xuan was criticized by various scholars of the era for incorrectly depicting events that occurred in the Southern Tang. The Jiangbiao zhi by Zheng Wenbao and the Jiangnan bielu by Chen Pengnian both in a partisan manner to fix these supposed errors.[107] Later historians like Wang Anshi and Ouyang Xiu likewise critiqued the Jiangnan lu.[108]

The Diaoji litan (釣磯立談) was composed by a private citizen of the Southern Tang after its conquest by the Song. In the work the author defended the legacy of the Southern Tang. The Tang-Song interregnum was conceived as a period were competing states potentially had a limited mandate of heaven. They called the Southern Tang a “peripheral hegemonic state” (偏霸). An account was given of the Southern Tang geopolitical position and its plans for unifying China. By utilizing this terminology and logic the author disputed the negative status given to the Southern Tang by Song historians.Template:Cho-ying

The Zizhi Tongjian is an authoritative historical text published in 1084 that remains an important source for Chinese historiography. Sima Guang oversaw and edited the compilation that covered 1,300 years of Chinese history. Contemporary scholars have noted that his personal biases removed a sense of objectivity in the text. The opinions expressed in the work nonetheless remained influential for centuries.[109]

The final chapters of the Zizhi Tongjian deal with the Southern Tang. They provide significant amount of information about the state.[110] Leaders of the southern states that claimed the title of emperor were instead referred to as "ruler" (主).[111]

Ouyang Xiu largely followed the Zizhi Tongjian in his treatment of the Southern Tang. However his work has been seen as less accurate than the Zizhi Tongjian by contemporary scholars.[110] He also authored a treatise on political legitimacy, determining that the principal factor lay in controlling a unified Chinese state. He laid out how to determine the legitimacy of a regime without necessarily giving into personal or cultural biases.[112] He postulated that there were interregnums where no authority was necessarily legitimate.[113]

In 1355 Yang Wei-chen wrote an essay critiquing the recently published Song shi. In it he questioned the prevailing belief that the Southern Tang weren't a legitimate political entity. He recorded statements from Taizu and Qubilai that supposedly demonstrated the importance of controlling Southern China to acquire political legitimacy. Neither quotation appears in any other historical sources, making them of doubtful authenticity.[105]

Rulers

| Temple Names | Posthumous Names | Personal Names | Period of Reigns | Reign periods and dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convention for this kingdom only : Nan (Southern) Tang + posthumous names. Hou Zhu was referred to as Li Hou Zhu (李後主 Lǐ Hòu Zhǔ) | ||||

| Liè Zǔ or Xian Zhu (先主 Xiān Zhǔ) |

Too tedious thus not used when referring to this sovereign | 李昪 Lǐ Biàn | 937–943 | Shengyuan (昇元 Shēng Yuán) 937–943 |

| Yuan Zong or Zhong Zhu (中主 Zhōng Zhǔ) |

Too tedious thus not used when referring to this sovereign | 李璟 Lǐ Jǐng | 943–961 | Baoda (保大 Bǎo Dà) 943–958 Jiaotai (交泰 Jiāo Tài) 958 Zhongxing (中興 Zhōng Xīng) 958 |

| Hou Zhu (後主 Hòu Zhǔ) or Wu Wang (吳王 Wú Wáng) |

None | 李煜 Lǐ Yù | 961–975 | (Under Li Yu, the Southern Tang did not have its own titles for reign periods) |

Southern Tang and Wu rulers family tree

| Southern Tang and Wu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

– Wu emperors; – Southern Tang emperors

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Citations

- Kurz 2011, p. 27.

- Kurz 2011, p. 89.

- Mote 1999, p. 14.

- Kurz 2014, pp. 602-603.

- Sima 1084.

- Clark 2009, pp. 165-167.

- Krompart 1973, p. 228.

- Krompart 1973, p. 174.

- Krompart 1973, p. 236.

- Krompart 1973, p. 27.

- Krompart 1973, pp. 271-272.

- Krompart 1973, p. 282.

- Kurz 2011, p. 26.

- Kurz 2014, p. 619.

- Kurz 2011, p. 33.

- Kurz 2011, p. 38.

- Krompart 1973, p. 271.

- Clark 2009, p. 174.

- Mote 1999, p. 21.

- Lamouroux 1995, pp. 163-165.

- Krompart 1973, p. 26.

- Clark 2009, p. 205.

- Hartill 2005, p. 113.

- Clark 2009, p. 187.

- Horesh 2013, pp. 375-376.

- Ashkenazy 2016.

- Hartill 2005, pp. 119-120.

- Kokotailo 2018.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 87-88.

- KKNews 2016.

- Ashkenazy 2015.

- Kao 2015.

- Lee 2004, pp. 4-6.

- Lee 2004, p. 18.

- Lee 2004, p. 8.

- Lee 2004, p. 38.

- Lee 2004, p. 26.

- Lee 2004, p. 37.

- Standen 1994, p. 274.

- Kote 1999, pp. 9.

- Lorge 2005, pp. 18-19.

- Clark 2009, pp. 89-90.

- Krompart 1973, p. 303.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 34-35.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 28-29.

- Standen 2009, p. 93.

- Standen 2009, pp. 97-98.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 60-62.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 63-64.

- Kurz 2011, p. 69.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 71-75.

- Lorge 2013, p. 112.

- Lorge 2005, pp. 27-28.

- Kurz 2011, p. 75.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 76-79.

- Lorge 2013, p. 118.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 80-84.

- Clark 2009, p. 201.

- Lorge 2013, p. 121.

- Lorge 2005, p. 32.

- Lorge 2005, p. 39.

- Lorge 2013, pp. 108-110.

- Kurz 2011, p. 34.

- Krompart 1973, p. 304.

- Kote 1999, pp. 14-15.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 52-53.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 55-57.

- Kurz 2011, p. 36.

- Kurz 2011, p. 62.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 76-78.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 107-108.

- Sima 1084, vol. 289.

- Sima 1084, vol. 290.

- Kurz 2011, p. 66.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 65-67.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 67-68.

- Clark 2009, pp. 198-199.

- Sima 1084 vol. 291.

- Krompart 1973, p. 238.

- Twitchett & Tietze 1994, p. 72.

- Krompart 1973, p. 306.

- Li 2016, p. 36.

- Lee 2004, p. 28.

- Li 2016, p. 45.

- Standen 2009, p. 106.

- Standen 2009, pp. 102-103.

- Twitchett & Tietze 1994, pp. 80-81.

- Kurz 2011, p. 60.

- Standen 1994, p. 44.

- Standen 1994, p. 46.

- Li 2016, p. 37.

- Standen 1994, p. 49.

- Kurz 2011, p. 35.

- Krompart 1973, p. 307.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 89-90.

- Kurz 2011, p. 93.

- Kurz 2011, p. 95.

- Clark 2009, p. 204.

- Lorge 2005, p. 40.

- Twitchett & Tietze 1994, p. 85.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 103-104.

- Kurz 2011, p. 106.

- Kurz 2011, pp. 110-113.

- Woolley 2014, pp. 558-560.

- Davis 1983, p. 67.

- Kurz 1994, pp. 219-220.

- Kurz 1994, pp. 221-222.

- Woolley 2014, p. 549.

- Chan 1974, pp. 37-38.

- Kurz 1994, p. 224.

- Woolley 2014, p. 553.

- Davis 1983, pp. 38-39.

- Davis 1983, p. 62.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Guang, Sima (1084). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Ji, Yun (1798). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Li, Tao (1193). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Lu, You (1184). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Ma, Ling. (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Ouyang, Xiu (1073). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Toqto'a (1343). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Wenying (1078). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Xue, Juzheng (974). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- Zheng, Wenbao (978). (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

Books

- Clark, Hugh R. (2009). "The Southern Kingdoms between the T'ang and the Sung, 907–979". In Twitchett, Denis; Smith, Paul J. (eds.). The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1. The Cambridge History of China. 5. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 133–205. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1.

- Hartill, David (2005). Cast Chinese coins. Trafford: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1412054669.

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2011). China's Southern Tang Dynasty (937-976). Routledge. ISBN 9780415454964.

- Kurz, Johannes (2011). "Han Xizai (902–970): An Eccentric Life in Exciting Times". In Lorge, Peter (ed.). Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. Hong Kong: China University Press. pp. 79–98. ISBN 962996418X.

- Kurz, Johannes (1997). "The Yangzi in the Negotiations between the Southern Tang and Its Northern Neighbors (Mid-Tenth Century)". In Dabringhaus, Sabine; Ptak, Roderich; Teschke, Richard (eds.). China and Her Neighbours: Borders, Visions of the Other, Foreign Policy 10th to 19th Century. South China and maritime Asia. 6. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3447039426.

- Lorge, Peter (2013). "Fighting Against Empire: Resistance to the Later Zhou and Song Conquest of China". In Lorge, Peter A. (ed.). Debating War in Chinese History. Leiden and New York: Brill. pp. 107–140. ISBN 978-90-04-22372-1.

- Lorge, Peter A. (2005). War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-31690-1.

- Mote, F. W. (1999). Imperial China (900-1800). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674012127.

- Standen, Naomi (2009). "The Five Dynasties". In Twitchett, Denis; Smith, Paul J. (eds.). The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1. The Cambridge History of China. 5. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–132. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1.

- Twitchett, Denis; Tietze, Klaus-Peter (1994). "The Liao". In Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis (eds.). Alien regimes and border states, 907—1368. The Cambridge History of China. 6. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–153. ISBN 0-521-24331-9.

- Wu, John C. H. (1972). The Four Seasons of Tang Poetry. Charles E. Tuttle. ISBN 978-0804801973.

Articles

- Chan, Ming K. (1974). "THE HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE TZU-CHIH T'UNG-CHIEN: A SURVEY". Monumenta Sercia. 31: 1–38 – via JSTOR.

- Cho-ying, Li (2018). "A Failed Peripheral Hegemonic State with a Limited Mandate of Heaven: Politico-Historical Reflections of a Survivor of the Southern Tang". Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies. 48: 243–285. doi:10.6503/THJCS.201806_48(2).0002 – via Airiti.

- Davis, Richard (1983). "Historiography as Politics in Yang Wei-chen's 'Polemic on Legitimate Succession'". T'oung Pao. 69: 33–72 – via Brill.

- Horesh, Niv (2013). "'CANNOT BE FED ON WHEN STARVING': AN ANALYSIS OF THE ECONOMIC THOUGHT SURROUNDING CHINA'S EARLIER USE OF PAPER MONEY". Journal of the History of Economic Thought. 35: 373–395 – via Cambridge University.

- Kurz, Johannes (2016). "On the Unification Plans of the Southern Tang Dynasty". Journal of Asian History. 50: 23–45 – via JSTOR.

- Kurz, Johannes (2016). "Song Taizong, the 'Record of Jiangnan' ('Jiangnan lu'), and an Alternate Ending to the Tang". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 46: 29–55. doi:10.1353/sys.2016.0003 – via Project MUSE.

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2014). "On the Southern Tang Imperial Genealogy". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 134: 601–620 – via JSTOR.

- Kurz, Johannes (2012). "The Consolidation of Official Historiography during the Early Northern Song Dynasty". Journal of Asian History. 46: 13–35 – via JSTOR.

- Kurz, Johannes (1998). "The Invention of a "Faction" in Song Historical Writings on the Southern Tang". Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies. 28: 1–35 – via JSTOR.

- Kurz, Johannes (1994). "Sources for the History of the Southern Tang (937-975)". Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies. 24: 217–235 – via JSTOR.

- Lamouroux, Christian (1995). "Crise politique et développement rizicole en Chine : la région du Jiang-Huai (VIIIe - Xe siècles)". Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient (in French). 82: 145–184.

- Lee, De-nin D. (2004). "Fragments for Constructing a History of Southern Tang Painting". Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest. 34: 1–39 – via JSTOR.

- Li, Man (2016). "Where is 'Yingyou' : the 'Tea Route' between Khitan and Southern Tang and its ports of departure". National Maritime Research. Shanghai. 2: 31–46. ISBN 978-7-5325-8037-8 – via Academia.edu.

- Woolley, Nathan (2014). "From restoration to unification: legitimacy and loyalty in the writings of Xu Xuan (917–992)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 77: 547–567. doi:10.1017/S0041977X14000536 – via Cambridge University Press.

Theses

- Kim, Hanshin (2012). The Transformation in State and Elite Responses to Popular Religious Beliefs (PhD thesis). University of California, Los Angeles.

- Krompart, Robert J. (1973). The Southern Restoration of T'ang: Counsel, Policy, and Parahistory in the Stabilization of the Chiang-Huai Region, 887–943 (PhD thesis). University of California, Berkeley.

- Standen, Naomi (1994). Frontier crossings from north China to Liao, c.900-1005 (PhD thesis). Durham University.

Websites

- Ashkenazy, Gary (10 June 2015). "Vault Protector Coins". Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Ashkenazy, Gary (16 November 2016). "Chinese coins – 中國錢幣". Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Kao, Garry (21 August 2015). "收藏迷带你深度游钱币博物馆" (in Chinese). 蝌蚪五线谱. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- KKNews (23 December 2016). "中國古代花錢:鎮庫錢,古代錢幣文化寶庫中的一顆明珠" (in Chinese). Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Kokotailo, Robert (2018). "Chinese Cast Coins - SOUTHERN T'ANG DYNASTY AD 937-978". Calgary Coin & Antique Gallery – Chinese Cast Coins. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

.jpg.webp)