Napoleonic looting of art

The Napoleonic looting[1] (Italian: Furti napoleonici) was a series of removals of goods, particularly works of art and precious objects, carried out by the French Army (or Napoleonic officials) in the territories of the First French Empire, which included the Italian peninsula, Spain, Portugal, the Low Countries and Belgium, and Central Europe. The looting continued for over twenty years, from 1797 and ending around the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[2]:113

.png.webp)

During the Napoleonic era, an unknown but immense quantity of European artworks were lost, destroyed, or acquired as a condition of treaties and through unsanctioned seizures. French officials planned to remove the frescoes in the Raphael Rooms at the Vatican and to send Trajan's Column to France, likely in pieces.[3] Napoleonic soldiers burned the Bucintoro, the flagship of the Italian fleet, perhaps to reclaim the gold of its ornamentation; collected the treasures of the Basilica San Marco to pay army wages; and dismantled the Arsenal of Venice. They also cut a large Rubens, The Gonzaga Trinity, into pieces so they were easier to sell and sent two of its side panels to Nancy and Antwerp, where they are today.[4] French officials justified taking art and objects of value both as a right of conquest and as an advancement of public education, encyclopedism, and Enlightenment ideals.

These seizures redefined the understood right of conquest in Europe, and caused a surge of public interest in European art and art conservation. The prolific transfer of wall murals and panel paintings reflected new French conservation techniques.[5] During the Congress of Vienna, Austria, Spain, the German states, and England ordered the immediate restitution of all the removed artworks "without further diplomatic negotiation". Many works were returned, but many remained in France due to resistance from the French administration and the extremely high costs the European states faced for transporting the stolen works.[6] With not all the works returned, Napoleonic looting continued to affect European politics, museology, and national cultural identity.

History

The Louvre and French cultural conquest

After the French Revolution, the new government had to make decisions about whether to or how to nationalize artworks from churchs, the fled nobility of the Ancien Régime, and the royal collections.[7] Most were placed for storage or display in the Louvre. After the Louvre's public re-opening in 1793, however, the French government developed plans to increase its collection through the confiscation of foreign artworks as a show of national strength.[7] From the start of the 18th century on, the French people had clamored for increased public art exhibitions, creating a need for new displays and new artworks.[8]:677 The French art appropriations after 1793 were at first indiscriminate looting, but by around 1794, the French government had developed structured programs for the acquisition of art during the Republic's wars.[9] Those programs were supported through the design of peace treaties to legitimate these acquisitions: some treaty articles required the delivery of works of art, and others imposed taxes to nobility as tribute.

As the French army conquered territories in the War of the First Coalition, their artworks were taken to French museums, particularly the Louvre where Napoleon had wished in 1795 to create the Musee des Monuments Francais.[9] Earlier in European history, the plundering of artworks was a common, and accepted, means for conquerors to express power over their new subjects.[2]:115–116 Beginning in the late 18th century, however, the increased national control of artworks created regulations and precedents that restricted the movement and sale of artworks; and the ideals of enlightened monarchs discouraged treating art objects as subject to plundering.[2]:116

Still, the French justified the looting of artworks by appealing to the right of conquest and republican ideals of artistic appreciation.[2]:124 One petition of French artists maintained that the works would serve as inspiration for the progress of republican art and to educate the French public as they did when Romans brought Greek art to Rome. A lieutenant of the Hussars believed that the works had remained "soiled too long by slavery" and said, "These immortal works are no longer on foreign soil. They are brought to the homeland of arts and genius, to the homeland of liberty and sacred equality: the French Republic." A French general, François-René-Jean de Pommereul, argued, "The statues that the French have taken from the degenerate Roman Church to adorn the great Museum of Paris, to distinguish the most noble trophies, the triumph of liberty over tyranny, of philosophy over superstition."[6]:439 The bishop Henri Gregoire said before the Convention in 1794: "If our victorious armies have entered Italy, the removal of the Apollo Belvedere and the Farnese Hercules should be the most brilliant conquest. It is Greece that decorated Rome: why should the masterpieces of the Greek republic decorate a country of slaves? The French Republic should be their final resting place."[10][2]:119

Some such as Quatremère de Quincy, student of Winckelmann and adherent to custom of the Grand Tour, believed artworks should not be removed from their original context. Beginning in 1796, Quatremère argued against the rhetoric of the Napoleonic administration. To rediscover the art of the past, he said it would be necessary to "turn to the ruins of Provence, investigate the ruins of Arles, Orange, and restore the beautiful amphitheater of Nimes," instead of looting Rome. Even though Quatremère supported the centralization of cultural knowledge,[2]:128 he believed that uprooting art from its context of creation and its final location, as French officials were doing at the time, hopelessly compromises its authentic meaning and creates a new one, alien to its original purpose.[5]

These ideals stood in opposition to the perceived growing need to use art and cultural objects to exalt republican ideals and French national identity,[2]:117 as well as the use of natural history collections for the advance of scientific knowledge.[11]:20 French citizens used the "scientific cosmopolitanism" of the Republic of Letters to justify their acquisitions. The "savant" system, whereby experts would select the works of interest to be taken, was adopted to reconcile imperial tribute with the stated French values of encyclopedism and public knowledge.[11]:21,27

Quatremère's views were in the minority of French society, but the conquered nations made appeals along similar lines. In occupied Belgium, there were popular protests against art expropriation, and the Central and Superior Administration of Belgium worked to block French acquisitions. In some cases, the administration argued that Belgians shouldn't be treated as a conquered subjects but "children of the Republic".[2]:125 In Florence, the director of the Uffizi argued that the galleries' collection was already owned by the people of Tuscany, rather than the Grand Duke who had signed a treaty with the French. In some cases, these causes were actually supported by French officials. For example, Charles Nicolas Lacretelle argued that taking Italian art in excess would push Italians to support Hapsburg rule.[2]:127

The influx of paintings to the Louvre also coincided with a renewed interest in art restoration methods under the influence of chemist and restorer Robert Picault. Those new cultural preservation methods were then used to justify the seizure and alterations of foreign cultural objects.[2]:117 Some paintings that arrived in Paris were restored or altered, like Raphael's Madonna of Foligno, which was transferred from its original panel to a canvas support in c. 1800. The French army's risky removal of murals and frescoes was closely associated with French conservators' tradition of transferring paintings onto new supports. The detachment of wall paintings was viewed as similar to moving a wooden altarpiece from its place, although it's hard to separate this enthusiasm from Napoleon and Vivant Denon's desire to acquire more art.[5] These radical treatments were difficult to execute successfully. In 1800, French officials tried to remove the Deposition by Daniele da Volterra in the Orsini chapel of Rome's Trinità dei Monti. The stacco a massello technique used undermined the walls of the chapel, and the removal had to be halted to prevent the chapel from caving in.[5] The mural itself had to be extensively restored by Pietro Palmaroli and was never sent to Paris, although others murals from the church were.

.jpg.webp)

After 1800, the collection for the Louvre became more organized under the directorship of Dominique-Vivant Denon, who traveled personally during the war campaigns to Egypt, Italy, Germany, Austria, and Span to select artworks for France.[12]:183 Denon, known as "Napoleon's eye",[13]:33 adjusted the layout of the Louvre to encourage holistic comparisons of the plundered artworks, reflecting new ideas in museology and countering the objections that the artworks lacked a meaningful context in France.[2]:133 Denon was supported by a commission of specialists and "deployed flattery and duplicity" to support further acquisitions, even against Napoleon's wishes.[2]:132 As a result of the Chaptal Decree in 1801, works of greater merit were selected for the Louvre, while the less important ones were distributed among the French provincial museums (e.g., Reims, Arles, Tours).[8]:679

The Low Countries and the Rhineland

After the War of the First Coalition, the French armies began claiming property from within the newly formed Batavian Republic, [2]:125 including from the collection of the Orange family at The Hague. In 1794, three Rubens paintings along with around 5,000 books from the University of Louvain were sent from Antwerp to Paris.[6]:440 The first one arrived in September 1794.[8]:678 The Louvre received around 200 Flemish old master paintings, among which were 55 Rubens and 18 Rembrandts,[14] as well as the Proserpina sarcophagus and several marble columns from the Aachen Cathedral.[6]:443

In early 1795, one of the "savant" commissions comprising botanist André Thouin, geologist Barthélemy Faujas de St-Fond, antiquarian Michel Le Blond, and architect Charles de Wailly reached the collection of Stadholder William V, who had fled.[11]:21–22 However, the status of the Batavian Republic as a "sister republic" to France made the acquisition difficult to justify. In March 1795, French officials exempted all Batavian private property from seizure, except for the Stadholder's, relying on his public unpopularity.[11]:24 With the collection designated as private property and eligible for appropriation, four shipments of natural history artifacts (minerals, stuffed animals, books, etc) and 24 paintings were shipped to Paris in the late spring of 1795.[11]:23

These works were selected by a special commission of artists and scholars appointed by the French government in 1794 and were claimed both as tributes and for their political effect. As Thouin described:

This tribute by a vanquished power will contribute much to perpetuate the glory of the victors, and make the nieghboring powers tributary of France by forcing its subjects to draw on France for useful knowledge. It is undoubtedly the least expensive tribute to extract from the conquered, the most dignifying for the great people who impose it, the most fruitful for the goodness of humanity, a goal which any good government should never lose sight of.[11]:26

The commission's process was used to design the systematic appropriations that were to come.[9] The first exhibitions of the Low Country artworks took place in 1799, and included 56 Rubens, 18 Rembrandts, Van Eyck's Ghent Altarpiece, and 12 portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger.[12]:180

Italy

In Italy, the system of a special commission used in the Netherlands and Belgium was expanded. In Lombardy, the Veneto, and Emilia-Romagna, the commission members had the authority to select and acquire works at their own discretion.[9] The policy of transferring to France the goods of the Italian occupied territories came from a specific order of the Directorate, sent to Napoleon on May 7, 1796:

General citizen, the executive directorate is convinced that the glory of art and that of the army under your orders are inseparable. Italy owes art the greater part of its riches and its fame, but the time of French rule has come, to consolidate and beautify the kingdom of liberty. The national museum should hold all celebrated artistic monuments, and you will not fail to enrich it with what awaits it from the armed conquest of Italy and those that the future still holds. This glorious campaign, as well as allowing the Republic to offer peace to its enemies, should repair the devastating vandalisms by adding to the splendor of military victories the enchantment of consoling and beneficial art.[15]

Regions that were either favorable to French rule, like those that eventually formed the Cisalpine Republic,[16]:408 or geographically hard to reach had less artwork taken from them. Regions that actively fought the French, like Parma and Venice, had the transfer of artworks written as conditions of their surrender.[9] The French armies also dissolved monasteries and convents as they went, often taking the artworks that were abandoned or sold in haste as a result.[12]:180

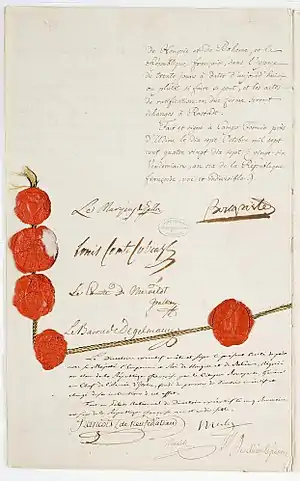

The first Napoleonic campaign in Italy carried away art objects of all kinds, from spring 1796 due to provisions in the Treaty of Leoben, the Armistice of Cherasco, the Treaty of Tolentino, and the Armistice of Bologna, and ending with articles in the Treaty of Campo Formio that transferred artworks from the Austrian Empire and (then dissolved) Venetian Republic in 1797. Over 110 artworks were brought to France in 1796 alone. Napoleonic officials continued to plunder artwork, beyond those agreed in the treaties, during the occupations—the commission had permission to amend the agreed number of artworks.[9] Resistance to these appropriations was decentralized, or sometimes nonexistent, because Italy did not exist as a single nation yet.[16]:409

Modena

The armistice between Napoleon and the Duke of Modena was made on the 17th of May in Milan by San Romano Federico d'Este, representative of Duke Ercole III. France demanded 20 paintings from the Este Collection and a monetary sum triple that of the Parma armistice.[6]:440 The first shipment was curated by Giuseppe Maria Soli, director of the Accademia Atestina di Belle Art. The paintings were seized from the apartment of the Duke D'Este and sent to Milan in 1796 with commissioners Tinet and Bethemly. After they arrived in France, they were judged mediocre by Charles-François Lebrun and Napoleon declared the armistice broken due to the violation of its clauses.

On October 14th, Napoleon entered Modena with two new commissioners, Pierre-Anselme Garrau and Antoine Christophe Saliceti, to sift through Modena's galleries of medals and the ducal palace for collections of cameos and engraved semi-precious stones.[17] On October 17th, after taking many manuscripts and antique books from the ducal library, they shipped 1213 items: 900 bronze imperial Roman coins, 124 coins from Roman colonies, 10 silver coins, 31 shaped medals, 44 coins from the Greek cities, and 103 Papal coins. All were sent to the Bibliotheque Nationale of Paris, where they are now.[18]

In February of 1797, Napoleon's wife Josephine took residence at the Ducal Palace of Modena and wished to see the collection of cameos and precious stones. She took around 200 of them, in addition to those taken by her husband. French officials also sent 1300 drawings found in the Este collections to the Louvre,[19] as well as 16 agate cameos, 51 precious stones, and many crystal vases.[20] On October 20, they took the bust of Lucio Vero and Marcus Aurelius, a drawing of the Trajan Column, and another with the busts of the emperors. The second shipment of paintings left on October 25th, when Tinet, Moitte, and Berthelmy chose 28 paintings to send to Paris, together with 554 other drawings and four albums, for a total of 800 drawings.

Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla

With the armistice of May 9th, 1796, the Dukes of Parma and Piacenza were forced to send 20 paintings,[6]:440 reduced to 16, selected by French officials. In Piacenza, they chose two canvases from the Cathedral of Parma—The Funeral of the Virgin and The Apostles at the Tomb of the Virgin by Ludovico Carracci—to sent to the Louvre. In 1803, by order of the minister Moreau de Saint Mery, the carvings and decorations of the Palazzo Farnese, as well as a painting The Spanish Coronation, were removed. Two paintings from the Duomo by Giovanni Lanfranco of Saint Alessio and Saint Corrado were taken. Ettore Rota published tables of all the art taken: 55 works from the Duke of Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla and 8 bronze objects of Veleja, of which 30 works and the 8 bronzes were eventually returned.[21] Saint Corrado by Lanfranco and The Spanish Coronation remain in France, where they are on display. The remaining works are missing.

In Parma, after 1803 and the creation of the Taro department, more precious objects were stripped from the Ducal archaeological museum, like Tabula Alimentaria Traianea and Lex Rubria de Gallia Cisalpina. One department prefect complained, after the departure of Vivant Denon, that "there remains nothing to serve as models for the schools of painting in Parma."[2]:134

Tuscany

In 1803, the Venus de' Medici was exported to France at the express order of Napoleon.[22] The later looting of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany was lead out by the director of the Louvre himself, Vivant Denon. Through the summer and winter of 1811, after the Kingdom of Etruria had been annexed by the French empire, Denon took artworks from dissolved churches and convents in Massa, Carrara, Pisa, then Volterra, and finally Florence.[12]:185 In Arezzo, Denon took The Annunciation of the Virgin by Giorgio Vasari from the Church of Santa Maria Novella d'Arezzo. For each, he noted which works should be sent to Paris. In Pisa, Denon selected nine paintings and a low-relief, all of which remain in France today.

In Florence, Denon searched the convent of Saint Catherine, the church Santa Maria Maddalena de' Pazzi, the church Santo Spirito, and the Accademia delle Belle Arti di Firenze and sent works from there to the Louvre. Fra Filippo Lippi's Barbadori Altarpiece was sent to the Louvre from the Santo Spirito,[23] and Michelangelo's unfinished sculptures for the tomb of Pope Julius II.[12]:185

Venetian Republic

The French search for artworks was lead by Monge, Berthollet, Berthelemy, and Tinet, who had previously been in Modena. Works of gold and silver from the Zecca of Venice and Basilica di San Marco were melted down and sent to France or used to pay soldiers' salaries.[24] Religious orders were abolished and around 70 churches were demolished. Around 30,000 works of art were sold or went missing.[25]

The Bucintoro, the Venetian state ship, was taken apart along with all its sculptures, which were burned on the island San Giorgio Maggiore to extract their gold leaf. The Arsenal of Venice was dismantled, and the most beautiful arms, armor, and firearms were sent to France and the rest (including more than 5,000 cannons) were melted down.[26][27] The weapons shipped to France were mostly placed in the collection of the Musee de l'Armee, including a bronze cannon made by La Serenissima to celebrate an alliance between the kingdoms of Denmark and Norway and the Republic of Venice.

.jpg.webp)

The Wedding at Cana by Veronese was cut in two and sent to the Louvre (where it remains). San Zeno Alterpiece by Mantegna was cut apart and sent as well. Its platforms today remain in the Louvre, while the principal panel was returned to Verona, breaking the work's integrity. The Gazola collection of fossils from Mount Bolca was confiscated in May 1797 and deposited in the Museum of Natural History in Paris that September. Gazola was retrospectively compensated with an annuity from 1797 and a pension from 1803.[28] He created a second collection of fossils, which were also confiscated and brought to Paris in 1806.[29]

In April 1797, the French removed the lion and famous bronze Horses of Saint Mark. When Napoleon decided to commemorate his victories of 1805 and 1807, he ordered the construction of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel and that the horses be placed on top as its only ornamentation.[6]:441 The Lion of Saint Mark and the horses were returned to Venice, although the lion statue broke before it could be returned to its place in the piazza.

Austrian Lombardy

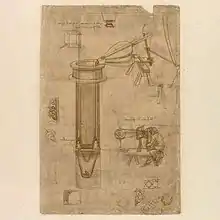

The French entered Milan in 1796 as part of the first Italian campaign of Napoleon. In May 1796, there was still fighting at Castello Sforzesco, commissioner Tinet had just been to the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, where he had taken the preparatory drawings of Raphael for the School of Athens at the Vatican; 12 drawings and the Codex Atlanticus of Leonardo da Vinci; the precious manscripts of the Bucolics of the Virgin with illuminations by Simone Martini; and five landscapes of Jan Brueghel for Carlo Borromeo that had been placed in the Ambrosiana of Milan in 1673.[30]

The Coronation of Thorns, by a follower of Titian between 1542 and 1543 and contracted by the monks of the Church of Santa Maria delle Graces, was sent to the Louvre. The Codex Atlanticus was eventually returned,[31] in pieces, to the library. In fact, many folios of the Codex are stored in Nantes and Basilea, while all the other notebooks and writings of Leonardo are at the national library of France, in Paris.[32] Many works were also taken from the Pinacoteca di Brera.

Sardegna

With the Armistice of Cherasco, 100 Italian and Flemish artworks fell to France. Turin was admitted to French territory, and the negotiations were particularly cordial.[33]:133 As a result, fewer works were taken from Sardegna, although French attention turned to the documents, the codices of the Regal Archive, and Flemish paintings in the Galleria Sabauda.

Naples

In 1799, General Jean-Étienne Championnet implemented the same policy in the Kingdom of Naples as a result of a missive sent on February 25th, 1799:

I announce to you with pleasure that we have found the riches we had thought lost. In addition to the Gessi of Ercolano that are at Portici, there are for you two equestrian statues of Nonius, father and son, in marble; the Venus Callipyge will not go alone to Paris, because we have found in the porcelain manufactory, the superb Agrippina that awaits death; the life-size marble statues of Caligula, of Marcus Aurelius, and a beautiful Mercury in bronze and ancient marble busts of great merit, among which one of Homer. The convoy will leave in a few days.[34]

The looting was not limited to paintings and sculpture but also took from patron libraries and goldsmiths. The brief institution of the Repubblica Napoletana in 1799 did immense damage to Neapolitan culture. Fearing the worse, the previous year, Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies had just transferred 14 masterpieces to Palermo. The French soldiers plundered many works: 1783 paintings were taken (several from the Gallerie di Capodimonte and the Palace of Capodimonte), of which 329 were from the Farnese collection and the rest were from Bourbon acquisitions. 30 were destined for the Republic, while the others were sold, particularly in Rome.

Rome and the Papal State

After the armistice, the Papal State sent over 500 manuscripts and 100 artworks to France on the condition that the French army would not occupy Rome.[9] The artworks were chosen by Joseph de la Porte du Theil, a French intellectual that knew the Vatican library well. He took, among others, the Fons Regina, the library of Queen Cristina of Switzerland. The Pope had to pay the costs of transporting the manuscripts and artworks to Paris. Seizures also took place in the Vatican Library, the Biblioteca Estense of Modena, those of Bologna, Monza, Pavia, and Brera and the Biblioteca Ambrosiana of Milan. The Treaty of Tolentino added works from the treasuries of Ravenna, Rimini, Perugia, Loreto, and Pesaro.[6]:441 Perugia was particularly badly hit. Commission member Jacques-Pierre Tinet took the Raphael altarpieces ceded through the Treaty of Bologna but also an additional 31 paintings, a number by Raphael and Perugino.[9] In the Vatican, the Napoleonic officials opened the rooms of the Pope, looting both for themselves and Napoleon, and fused Vatican medals of gold and silver for easier transportation. The private library of Pope Pius VI was seized by Pierre Daunou, a French official, after it was put up for sale.[6]:445 In August 1796, Roman rioters attacked French commissioners to protest the appropriations.[6]:441 The Swiss sculptor Heinrich Keller described the chaotic scene in Rome:

"The destruction here is awful; the most beautiful pictures are sold for a song. The holier the subject, the cheaper the picture. Yesterday I went to the Capitol and received the oddest impression. Marc Antony is standing in a ktichen dressed with a heavy wooden neckpiece and gloves; the Dying Gaul is packed in straw and sack cloth to this toes, and the beautiful Venus de' Medici is buried to her bosom in hay, while Flora is standing in the lower corridors all nailed in a wooden crate."[12]:180

The French armies occupied Rome in 1798 after the assassination of General Duphot, exiling Pius VI and establishing the short-lived Roman Republic. Afterwards, Napoleonic officials were particularly interested in removing the frescoes in the Vatican's Raphael Rooms. General Pommereul also planned to remove the Trajan Column from Rome and send it to France, probably in pieces.[35] Pommereul's assistant, Daunou, wrote the proposal on April 15th, 1798: "We will send an obelisk," referring to the column. This proposal was blocked by the cost of transporting it and the administrative obstacles created by the Church to slow the process.[5] Daunou later wrote in May that the classical sculptures from Villa Albani filled over 280 crates, all to be sent to Paris.[12]:180

In 1809, collections of marbles were sold to Napoleon by Camillo, the Borghese prince, who was under significant financial strain due to the heavy taxation imposed by the French. The prince didn't received the promised sum, but was paid in land requisitioned from the Church and mineral rights in Lazio. (Following the Congress of Vienna, he had to return all these to their legitimate owners.)[36]

The catalog of Canova

As a papal diplomat, the sculptor Antonio Canova made a list of Italian paintings that were sent to France.[37] Below is the list, as reported by French sources, which also marks how many works were lost or repatriated. Canova was primarily concerned with figurative works and sculptures, leaving out the minor or decorative arts.[38]

| Place of Origin and Time of Taking | Works taken | Works returned in 1815 | Works left in France | Works lost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milan, May 1796 | 19 | 6 | 11 | 2 |

| Cremona, June 1796 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Modena, June 1796 | 20 | 10 | 10 | |

| Parma, June 1796 | 15 | 12 | 3 | |

| Bologna, July 1796 | 31 | 15 | 16 | |

| Cento, July 1796 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Modena, October 1796 | 30 | 11 | 19 | |

| Loreto, February 1797 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Perugia, February 1797 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Mantova, February 1797 | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| Foligno, February 1797 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Pesaro, 1797 | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

| Fano, 1797 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Rome, 1797 | 13 | 12 | 1 | |

| Verona, May 1797 | 14 | 7 | 7 | |

| Venice, Septembr 1797 | 18 | 14 | 4 | |

| Total 1796–1797 | 227 | 110 | 115 | 2 |

| Rome, 1798 | 14 | 0 | 14 | |

| Turin, 1799 | 66 | 46 | 20 | |

| Florence, 1799 | 63 | 56 | 0 | 7 |

| Turin, 1801 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Naples, 1802 | 7 | 0 | 7 | |

| Rome (San Luigi dei Francesi) | 26 | 0 | 26 | |

| Parma, 1803 | 27 | 14 | 13 | |

| Total 1798–1803 | 206 | 116 | 83 | 7 |

| Savona, 1811 | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Genoa, 1811 | 9 | 6 | 3 | |

| Chiavari, 1811 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Levanto, 1811 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| La Sapienza, 1811 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Pisa, 1811 | 9 | 1 | 8 | |

| Florence, 1811 | 9 | 0 | 9 | |

| Parma, 1811 | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

| Foligno, 1811 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Todi, 1811 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Perugia, 1811 | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| Milan (Brera), 1812 | 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| Florence, 1813 | 12 | 0 | 12 | |

| Total 1811–1813 | 73 | 23 | 50 | |

| Overall Total | 506 | 249 | 248 | 9 |

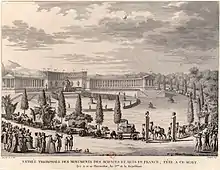

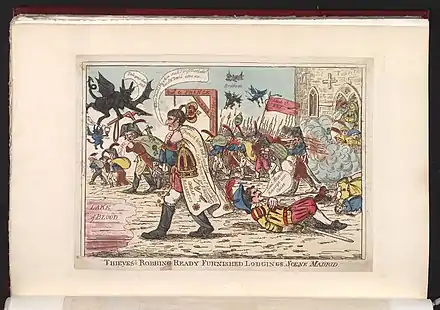

The celebrations

In the ninth and tenth day of Thermidor in Year 6 after the French Revolution (27th and 28th July, 1798), there was a grand celebration of Napoleonic military victory,[6]:437 for the arrival a third convoy carrying artworks from Rome and Venice.[2]:124 The event is represented in a print kept at the National Library of Paris.[39] It shows the first convoy of confiscated goods from the Italian campaign arriving at Champs de Mars in front of the Ecole Militaire of Paris, after it had traveled from the quay by the Jardin des Plantes.[2]

The triumphal parade was planned months ahead of time. For the occasion, the trees had been pruned and the students of the Ecole Polythecnique were called to participate in the festivities. In the prints, the Horses of Saint Mark are shown on a towed wagon with six horses, preceded by one with a cage of lions and followed by one with four camels. In front, a panel declares "La Grèce les ceda; Rome les a perdus; leur sort changea deux fois, il ne changera plus" (Greece has fallen; Rome is lost; their luck changed twice, it won't change again).[6]:438 The procession contained the Apollo Belvedere, the Venus de' Medici, the Discobolus, Laocoön group, and sixty other works among which are nine Raphaels, two Correggios, collections of minerals and antiques, exotic animals, and even manuscripts from the Vatican dating from 900 AD.[40] Popular attention was drawn by the exotic animals and the Basilica della Santa Casa, which was believed to be the work of Saint Luke.[41]

Egypt and Syria

After Italy, the Napoleonic army began its campaign in Egypt and Syria. The army brought a contingent of 167 scholars with it, including Vivant Denon and mathematician Jean Fourier. This scientific expedition undertook excavations and scientific studies.[6]:442 Looting from the area was not even considered a violation of international norms by Europeans, due to the influence of orientalism and European countries' tense international relations with the Ottoman Empire.[2]:124 Most of objects taken by the French army were lost to the British, including the sarcophagus of Nectanebo II and Rosetta Stone, after the Battle of the Nile in 1798, and were sent to the British Museum instead.[42] The French scholars' studies culminated in the Mémoires sur l'Égypte and the monumental Description de l'Égypte encyclopedia, which was finished in 1822.

Northern Europe

Following the Treaty of Lunéville between the French Republic and the Holy Roman Empire in 1801, manuscripts and codices began to flow from northern and central Europe to Paris.[6]:442 By 1806, Vivant Denon and his aides Daru and Stendhal began to systematically appropriate art from those regions, with the gallery of Cassel early on being relieved of 48 paintings. Enroute, the paintings were directed to Mainz, where the Empress Josephine saw them and convinced Napoleon to have them sent to Malmaison as a gift to her.[6]:444 In the end, Denon selected over 299 paintings to take from the Cassel collection.[12]:184 Nearly 78 paintings were taken from the Duke of Brunswick, as well as illuminated manuscripts and the famous art collection of the deceased Cardinal Mazarin.[6]:442

In all, over a thousand paintings were taken from German and Austrian cities, including Berlin, Vienna, Nuremberg, and Potsdam—400 objects came from Vienna alone [43]. As in Italy, many works were melted down for easy transport and sale, and two large auctions were held in 1804 and 1811 to fund further military action.[6]:445

Spain

During and after the Peninsular War, hundreds of artworks were seized from Spain up until the first abdication of Napoleon in 1814.[6]:443 Paintings by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Francisco de Zurbarán, and Diego Velázquez were all sent to Paris for display.[44] Most of the works were from the Spanish royal collection and were assembled at the Prado in Madrid, although the Spanish administration was successfully able to delay their shipment until 1813.[12]:186 The French looting was conducted under the command of Jean-de-Dieu Soult and officers like Horace Sébastiani, Jean Joseph Dessolles, and Armand de Caulaincourt.

Restoration and restitutions

%252C_da_hermitage.jpg.webp)

During the First Restoration, the allied nations did not initially stipulate the return of artworks from France. They were to be treated as "inalienable property of the Crown."[43] On May 8th of 1814, however, Louis XVIII declared that works not yet hung in French museums would be returned, which returned many of the Spanish works.[6]:446 Manuscripts were also returned to Austria and Prussia by the end of 1814, and Prussia recovered all its statues, 10 Carnachs, and 3 Correggios. The Duke of Brunswich recovered 85 paintings, 174 Limoges porcelains, and 980 majolica vases.[6]:449 But most of the works remained unreturned. After Napoleon's second surrender at Waterloo and the beginning of the Second Restoration, the return of art became a part of the negotiations, although the lack of historical precedent made them a messy affair.[42][2]:137[14][45]

The nations did not wait for finalized agreements from the Congress of Vienna to act. In July 1815, the Prussians began to force restitutions. Frederick William III of Prussia ordered von Ribbentropp, Jacobi, and Eberhardt de Groote to deal with the returns.[6]:450 On July 7th, they demanded Vivant Denon return all the Prussian treasures, but Denon opposed the order because it lacked specific authorization from then-king Louis XVIII. Von Ribbentropp threatened to have Prussian soldiers seize the works and imprison and extradite Denon to Prussia. By July 13, all the key Prussian works were out of the Louvre and packed up for travel.[46]

When the Dutch consul arrived at the Louvre to make similar requests, Denon also denied them access and wrote to Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord and the Congress of Viena:

"If we give up all the requests of the Netherlands and Belgium, we deny to the museum one of the most important assets, the Flemmings ... Russia is not against, Austria has just received everything, and practically also Prussia. There is only England, that has nothing to ask from the museum, but that has since stolen the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon, and now thinks to make competition with the Louvre, and wishes to loot this museum to collect the crumbs."[47]

The French wished to hold onto any objects they had seized and argued that keeping the artworks in France was a gesture of generosity towards their countries of origin and even a tribute to the cultural or scientific importance of those objects. For example, the French National Museum of Natural History denied the return of artifacts to the Netherlands in 1815, by claiming that it would necessarily break up the museum's complete collections. The natural historians offered to select and send an "equivalent" collection instead.[11]:28–29 In the end, with the aid of the Prussians, the delegates from the Low Countries grew so impatient that they took their works back by force.[12]:186

On September 20, 1815, Austria, England, and Prussia agreed that the remaining artworks should be returned and affirmed that there was no principle of conquest that would permit France to retain its spoils. The Russian tsar Alexander I of Russia was not part of this agreement, and preferred to make a compromise with the French government,[6]:451 having just acquired for the Hermitage 38 artworks sold by descendants of Josephine Bonaparte to resolve her debts. He had also received a gift from her shortly before her death in 1814—the Gonzaga Cameo from the Vatican.[48] After the Vienna agreement was complete, the occupying forces of Paris continued to remove and send artworks to the Spain, Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, and some Italian cities.

The French resented the returns and argued that they illegal, since they didn't have the force of treaty. Writing about a shipment of paintings to Milan, Stendhal said, "The allies took 150 paintings. I hope to be authorized to observe that we have taken them through the Treaty of Tolentino. The allies took our paintings without a treaty."[49] On the repatriation of Giulio Romano's The Stoning of Saint Stephen to Genoa, Vivant Denon maintained that the work "was offered as tribute to the French government from the city council of Genoa" and that transportation would risk the fragility of the work.[50]

In comparison to the other nations, the Italian cities were disorganized and without the support of a national army or diplomatic corp to make official requests. Unlike the confiscated artworks in the Netherlands, Belgium, and the Rhenish countries, Napoleon had legalized all the transfers of artwork through treaties in Italy. The sculptor Antonio Canova had been sent on a diplomatic mission by the Vatican to the peace conference for the second Treaty of Paris in August 1815.[6]:455 Canova sent letters asking for Wilhelm von Humboldt and Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh to support the return of Italian artworks and annul the conditions of the Treaty of Tolentino. In September, Canova also met with Louis XVIII and their audience together eased French resistance to the repatriations.[42] By October, Austria, Prussia, and England agreed to support his efforts, which returned many statues and sculptures. The Vatican manuscripts were restored by Marino Marini, the nephew of a Vatican librarian, as well as lead type that had been seized from the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples.[6]:455

As was written in the London Courier on October 15th, 1815, the public opinion of the allied countries was raised against the French:

"The disbanded officers of the army resort to Paris; and going about out of uniform, influence the populace. As the foreign troops withdraw, the insolence of the Parisians increases. They clamour loudly for the removal of the articles of Art. And why? By what right? The right of conquest? Then have the not twice lost them? Do they persist in enforcing that right? Then why do not now the Allies plunder France of every article worth removing which she possessed before Buonaparte's time? They are entitled to do this by the example of Buonaparte's practice, now so eagerly sanctioned by the Parisians.[6]:446

As the Lord Liverpool said to the English representatives in Paris: "The reasonable part of the world are for general restoration to the original possessors, but they say with truth that we have a better title to such objects; and they blame the policy of leaving the tropies of the French victories in Paris... It is most desirable, in point of policy, to remove them if possible from France, as whilst in that country they must necessarily have the effect of keeping up the remembrance of their former conquests and of cherishing the military spirit and vanity of the nation."[6]:447 The Courier wrote on October 4, 1815: "The Duke of Wellington came to the diplomatic conferences with a note in his hand, by which he expressly required all works of Art should be restored to their respective owners. This excited great attention, and the Belgians, who have immense claims to make, had been hitherto obstinately refused, did not wait to be told that they could begin to take back what was theirs. ... The brave Belgians are even now on the way to returning their Potters and their Rubens."[6]:448

The conditions under the 1815 Treaty of Paris required that any artworks to be returned had to be properly identified and returned to the nation they originated from. These conditions made it difficult to determine where some of the paintings should be sent. For example, some Flemish paintings where mistakenly returned to the Netherlands, rather than Belgium.[8]:681 The treaty also required effort from the conquered nations for their art to be returned. The situation was only partially resolved when the British offered to finance the costs of repatriating some artworks to Italy,[42] with the offer of 200,000 lire to Pope Pius VII.[12]:186

For various reasons, including lack of money, knowledge of the theft, or appreciation for the value of the taken works,[12]:186 the restored governments did not always pursue the return of the appropriated paintings. The governor of Vienna did not request the Lombardic artworks taken from churches, like The Crowning with Thorns by Titian. Ferdinand VII of Spain refused the return of several old master paintings when they were offered by the Duke of Wellington. They were taken to London instead.[51] The Tuscan government, under the Hapsburg-Lorraines, did not request works like the Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata by Giotto, Maesta by Cimabue, or the Coronation of the Virgin by Beato Angelico. Parma, under the ex-wife of Napoleon Maria Luigia, compromised and left half of its works in France. The Papal government did not ask for everything, especially paintings held by French provincial museums, like many taken from Perugia, to not disturb the re-Catholicization of a French countryside that was recovering from Jacobinism.

The Horses of Saint Mark were returned to Venice (not Constantinople, where they were originally taken by the Venetians), but it took workers over a week to remove them from the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel. The streets around the Arc were kept blocked by Austrian dragoons to prevent any interference with the removal.[42] The Lion of Saint Mark was dropped and broke while it was being removed from a fountain.[6]:452,456 On October 24, 1815, after the negotiations, a convoy of 41 carriages was organized that, escorted by Prussian soldiers, traveled to Milan. From there, the artworks were distributed to their legitimate owners across the peninsula. Around half of the works taken remained in France.[43]

Legacy

Between 1814 and 1815, the Musee Napoleon (the Louvre's name at the time) was dismantled. From its opening, artists and scholars, like Charles Lock Eastlake, had flocked to the museum to see its expansive, exhaustive collection.[12] One English artist, Thomas Lawrence, expressed sorrow at its dissolution, despite the injustices that lead to its creation.[51]:144 Still, the museum's impact remained:

The great museum of Napoleon did not end with the dispersion of its materials and masterpieces. Its example outlived him, contributing decisively to the formation of all the European museums. The Louvre, the national museum of France, had shown for the first time that the artworks of the past, even if collected by princes, belonged in relation to their people. And this principle (with the exception of the British royal collection) inspired the great public museums of the 1800s.[52]

— Paul Wescher

Art historian Wescher also pointed out that, "The return of the stolen artworks itself had a noteable and unexpected effect ... It contributed to the creation awareness of national artistic heritages, an awareness that did not exist in the 1700s."[52] Oddly, the mass circulation of artworks during the Napoleonic era had actually increased the renown of artists that were otherwise unknown internationally.[16]

After 1815, European museums were no longer just a horde of artifacts—they were an expression of political and cultural power.[7] The Prado in Madrid, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the National Gallery in London were all founded after the Louvre's example.[12]:186 The conditions of the Treaty of Paris also set a nationalist precedent for future repatriations in Europe, like that of Nazi plunder in the 20th century.[8]:681[53]

The repatriations had been long and incomplete, and almost half of the looted artworks remained in France.[8]:682 As a condition for the return of the works, many of the artworks were required to be in a gallery for public display and were not necessarily returned to their original locations. For example, Perugino's Decemviri Altarpiece was only reinstalled in its chapel in Perugia in October 2019, although it is still incomplete.[9] The long time it has taken to return some appropriated works in turn has become an argument against their restitution, particularly with museums' adoption of "retention policies" in the 19th century.[7]

Attempts at requisition have continued, however, up to and including the present day. During the Franco-Prussian War, Bismark's Germany asked the France of Napoleon III to return works of art still held from the time of looting but never repatriated. Vincenzo Peruggia described his 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa as an attempt to restore the painting to Italy, claiming incorrectly that the painting had been stolen by Napoleon.[13]:83 In 1994, the then-general director of the Italian ministry of culture, Francesco Sisinni believed the conditions were right for the return of the The Wedding at Cana of Veronese. In 2010, the historian and Veneto official Estore Beggiatto wrote a letter to premiere dame Carla Bruni to urge the painting's return—the painting is still at the Louvre.[54]

Egypt has requested the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone, which was discovered and exported to the British Museum after the French occupation of Egypt.[55] And former Egyptian antiquities minister Zahi Hawass launched a campaign in 2019 to have the Dendera zodiac returned to Egypt. It was taken in 1799 by Vivant Denon.[56]

Artworks that remained in France

Modena

- Salome Receiving The Head of Saint John by Guercino, Musée des Beaux Arts, Rennes

- The Martyring of Saint Peter and Saint Paul by Francesco Camullo and Ludovico Carracci, Musée des Beaux Arts, Rennes

- Jesus Lamented by the Virgin by Guercino, Musée des Beaux Arts, Rennes

- The Vision by Guercino, Musée des Beaux Arts, Rennes

- The dream of Jacob of Cigoli, Nancy, Musée des Beaux Arts

- The Madonna with the Baby Jesus Giving Benediction by Guercino, Chambéry Musée d'Art et d'Histoire[18]

- The Madonna and the Baby Jesus and the Martyring of Saint Paul by Guercino, Toulouse, Musée des Augustines

- The Glory of All-Saints by Guercino, Toulouse, Musée des Augustines

- Saint Sebastian Tended by Irene by Francesco Cairo, Tours, Musée des Beaux Arts

- Saint Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata by Guercino, Magonza, Mittelrehinschers Landesmuseum[18]

- The Holy Family Contemplating the Baby Jesus Sleeping by Francesco Gessi, Clérmond-Ferrand, Musée des Beaux-Arts

- The Martyrdom of Saint Victoria by Giovanni Antonio Burrini, Compiégne, Musée National du Chateau

- The Martyrdom of Saint Christopher by Leonello Spada, Epernay, Notre Dame

- Joseph and His Wife of Putifarre by Leonello Spada, Lille, Musée des Beaux Arts

- Rinaldo and Armida by Alessandro Tiarini, Lille, Palais des Beaux Arts

- Saint Bernard of Siena Saving Carpi from an Enemy Army by Ludovico Carracci, Notre Dame Cathedral

- 1,300 drawings from the Gallerie Estensi, now at the Bibliothéque Nationale of Paris

Mantua

- Madonna of Victory by Andrea Mantegna, from Manua, Musee du Louvre

- Transfiguration of Christ by Rubens, Museum of Nancy

- The Baptism of Christ by Rubens, made for the Church of the Jesuit Trinity of Mantua, now at the Musee des Beaux Arts of Anversa

- Madonna della Vittoria by Andrea Mantegna, from Mantua's church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, now at the Louvre

- Adoration of the Shepherds with Saint Longino and Saint John the Evanglist by Giulio Romano, from the Basilica of San Andrea of Mantua, now at the Louvre

Lombardy

- The Preaching at Jerusalem by Carpaccio, from the Pinacoteca di Brera in Lombardy, now at the Musee du Louvre

- The Virgin Casio by Boltraffio, from the Pinacoteca di Brera in Lombardy, now at the Musee du Louvre

- Saint Bernard and Saint Louis by Moretto da Brescia, from the Pinacoteca di Brera in Lombardy, now at the Musee du Louvre

- Saint Bonaventue and Saint Anthony of Padua by Moretto da Brescia, from the Pinacoteca di Brera in Lombardy, now at the Musee du Louvre

- Sacred Family with Elizabeth, Joachim, and John the Baptist by Marco d'Oggiono, from the Pinacoteca di Brera in Lombardy, now at the Musee du Louvre

- Annunciation Triptych by Rogier Van Der Weyden, central panel at the Musee du Louvre, side compartments at the Galleria Sabauda

- The Dropsy, by Gerard Dou, Musee du Louvre

- The Adoration of the Magi by Defendente Ferrari, now at the Malibu Getty Museum

- Madonna in Glory by Defendente Ferrari, lost

- Virgin with Jesus and Saint John the Baptist by Lorenzo Sabatini, Musee du Louvre

Tuscany

- Coronation of the Virgin by Beato Angelico taken from the Convent of San Domenico in Fiesole, now at the Louvre

- Virgin with Child and Saint Dominic and Thomas Aquinas, by Beato Angelico, taken from the Convent of San Domenico in Fiesole, Hermitage Museum

- Crucifixion with the Torments and Saint Dominic, by Beato Angelico, taken from the Convent of San Domenico in Fiesole, Musee du Louvre

- The Sacrifice of Abraham by Sodoma, from Pisa

- The Virgin Crowned by Jesus and Other Saints panel painting by Cenobio Machiavelli, from Pisa

- Virgin and Child sculpture by Giovanni Pisano, from Pisa

- The Death of Saint Bernard by Orcagna, from Pisa

- Saint Benedict by Andrea del Castagno, from Pisa

- The Virgin, Jesus, and Saint Bernard by Cosimo Rosselli, from Florence

- The Virgin, Jesus, Saint Giuliano, and Saint Niccolo by Lorenzo di Credi, from Florence

- Virgin Embracing the Child, with Saint and Angels by Empoli, from Accademia delle Belle Arti di Firenze in Florence

- Saint John the Baptist and Two monks by Andrea del Castagno, from Accademia delle Belle Arti di Firenze in Florence

- The Virgin with Baby Jesus and Four Angels by Sandro Botticelli, from Accademia delle Belle Arti di Firenze in Florence

- Jesus Appearing to Mary Magdalene by Angelo Bronzino, from the Santo Spirito in Florence

- Bearing the Cross by Benedetto Ghirlandaio from the Santo Spirito in Florence

- The Coronation of the Virgin and Four Saints by Raffaellino del Garbo, Florence

- Coronation of the Virgin by Piero di Cosimo, Florence

- Virgin Embracing the Child and Two Saints by Mariotto Albertinelli, Florence

- Life of Christ by Taddeo Gaddi, Florence

- Saint Francis and The Miracle of Dying by Pesello Peselli, Florence

- Coronation of the Virgin by Ridolfo Ghirlandaio, Florence

- Coronation of the Virgin and Two Angels by Simone Memmi, Florence

- Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata by Giotto, originally from the Pisan church of Saint Francis, now at the Louvre

- Maesta by Cimabue, originally in the Pisan church of Saint Francis, now at the Louvre

- Holy Mary with Her Divine Son Amid the Angels by Turino Vanni, from the Convent of San Silvestro in Pisa, now at the Louvre

- The Visitation by Domenico Ghirlandaio, from the church of Santa Maria Maddalena de' Pazzi in Florence, now at the Louvre

- Saint Thomas Aquinas with the Doctors of the Church by Benozzo Gozzoli, from the Duomo of Pisa, now at the Louvre

- Madonna and Child with Five Saints by Jacopo da Pontormo, from the church of Sant' Anna sul Prato of Florence, now at the Louvre

- Presentation at the Temple by Gentile da Fabriano, from the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze, now at the Louvre

- Barbadori Altarpiece by Fra Filippo Lippi, from the Santo Spirito of Florence, now at the Louvre

- The Immaculate Conception with St. Anselm and St. Martin (Q18573638) by Giuseppe Maria Crespi, from Parma

Naples

- The Adoration of the Magi by Spagnoletto, Musee du Louvre

- The Sacred Family by Bartolomeo Schedoni, Musee du Louvre

- The Virgin with the Baby Jesus by Cimabue, Museum of Lilly

- Saint Luke and the Virgin by Giordano, Musee de Lyon

- Death of Sofonisba by Calabrese, Musee de Lyon

- The Visitation by Sabbatini, Montpellier

- Venus and Adonis by Vaccaro, Musee d'Aix-en-Provence

Rome and the Papal State

- Equestrian Portrait of the Spanish Ambassador by Van Dyck, from the Palazzo Braschi, Musee du Louvre

- Seated Man at the Foot of a Tree by Viruly, from the Palazzo Braschi, Musee du Louvre

- The Usurers Thrown Out of the Temple by Braschi, from the Palazzo Braschi, Musee du Louvre

- The Virgin, Jesus, and Saint John the Baptist by Giulio Romano, from the Palazzo Braschi, Musee du Louvre

- Saint Francis by Albani, from the Palazzo Braschi, Musee du Louvre

- Virgin and Jesus by Fasolo, from the Palazzo Braschi, Musee du Louvre

- The Virgin of Loreto, copy of Raphael, from the Palazzo Braschi, Musee du Louvre

- Emmaus by the Strozzi, from the Palazzo Braschi, Musee de Grenoble

- Saint Sebastian by Orbetto, from the Palazzo Braschi, Musee de Bordeaux

- Pietà with Saint Francis and Saint Mary Magdalene by Annibale Carracci, from the church of Saint Francis of Ripa, Musee du Louvre

- Salvator Mundi by Carlo Dolci, from the Villa Albani, Musee du Louvre

- Virgin and Jesus by Fasolo, from the Villa Albani, Musee du Louvre

- Virgin and Jesus by Vannucci, from the Villa Albani, Musee du Louvre

Other locations

- The Codex Atlanticus of Leonardo da Vinci, 44 folios, and 196 other ancillary drawings, originally stored at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, now stored at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris and the Musee des Beaux-Arts, Nantes

- The Wedding at Cana of Veronese, taken from a Benedictine refectory in Venice, now at the Louvre

- Marriage of the Virgin by Perugino, Caen, now at the Musee des Beaux-Arts

- Agony in the Garden (Mantegna, Tours)|Agony in the Garden by Andrea Mantegna, originally in Verona's San Zeno, now at the Tours' Musee des Beaux-Arts

- The Crucifixion of Andrea Mantegna, originally from Verona's San Zeno, now at the Louvre

- San Pietro Polyptych by Perugino, now at the Lione Musee des Beaux-Arts

- The Nativity by Filippo Lippo, from the convent of Santa Margherita of Prato, now at the Louvre

- Madonna with Child Enthroned with Saint John the Baptist and Mary Magdalene by Cima da Conegliano, now at the Louvre

- Resurrection by Andrea Mantegna, from Verona, now at the Tours' Musee des Beaux-Arts

- Madonna of Dove by Piero di Cosimo, now at the Louvre

- Christ Adored by the Angels, with Saint Bernard and Saint Sebastian by Carlo Bononi, now at the Louvre

- The Virgin Appearing to Saint Catherine and Saint Luke by Annibale Carracci, commissioned for the Cathedral of Reggio Emilia, now at the Louvre

- The Purification of the Virgin by Guido Reni, now at the Louvre

- The Return of the Prodigal Son by Leonello Spada, now at the Louvre

- The Patron Saints of the City of Modena by Guercino, now at the Louvre

- Saint Paul by Guercino, now at the Louvre

- Holy Mary with Her Divine Son by Taddeo di Bartolo, Musee du Grenoble

- Saint Anthony, the Abbot by Paolo Veronese, now at the museum of Caen

- The Triumph of Job by Guido Reni

- Christ and the Adulteress by Giuseppe Porta, now at the Bordeaux Musee des Beaux-Arts[57]

- Christ Mocked and Crowned with Thorns by Giambologna, now at the Bordeaux Musee des Beaux-Arts

- The Madonna with the Baby Jesus Giving Benediction by Guercino, now at the Chambéry Musée d'Art et d'Histoire

- The Holy Family Contemplating the Baby Jesus Sleeping by Francesco Gessi, now at the Clérmond-Ferrand Musée des Beaux-Arts

- The Martyrdom of Saint Victoria by Giovanni Antonio Burrini, now at the Compiégne Musée National du Chateau

- The Martyrdom of Saint Christopher by Leonello Spada, Epernay, Notre Dame

- Joseph and The Wife of Putifarre by Leonello Spada, Lille Musee des Beaux Arts

- Rinaldo Prevents Armada from Killing Herself by Alessandro Tiarini, Lille Musee des Beaux Arts

- Saint Bernard of Siena Saves Carpi from an Enemy Army by Ludovico Carracci, Notre-Dame de Paris

Repatriated artworks

Returned to Italy

- Belvedere Apollo

- Capitoline Venus

- Venus Italica

- The Laocoon group

- Head of Jove

- Horses of Saint Mark

- Venus de' Medici

- Amazzone Mattei

- The sarcophagus slab of Guidarello Guidarelli

- Transfiguration of Raphael Sanzio

- Portrait of Tommaso Inghirami by Raphael Sanzio

- Portrait of Leo X by Raphael Sanzio

- Madonna della seggiola by Raphael Sanzio

- Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia by Raphael Sanzio

- Portrait of the Cardinal Bibbiena by Raphael Sanzio

- Visitation by Raphael Sanzio

- Assumption of the Virgin

- Saint John the Baptist with the Saints Francesco Giralamo, Sebastian, and Anthony of Padua by Perugino

- Crucifixion of Saint Peter by Guido Reni

- Massacre of the Innocents by Guido Reni

- Fortune with a crown by Guido Reni

- Madonna with the Long Neck by Parmigianino

- Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Correggio

- The Cathedral of Saint Peter by Guercino

- Marriage of the Virgin by Giulio Cesare Procaccini

- Madonna with Child and the Saints Luigi Gonzaga and Stanislao Kostka by Giuseppe Maria Crespi

- Marie al sepolcro by Bartolomeo Schedoni

- Ecce Homo by Ludovico Cigoli

- Bringing Christ to the Tomb by Cavalier D'Arpino

- Lamentation of the Dead Christ with the Saints Francis, Claire, John the Evangelist, Marie Magdalene, and Angels by Annibale Carracci

- Mars and Venus by Antonio Canova

- Madonna with Child and Saint Christopher and Saint George by Defendente Ferrari, returned to the Caselle Torinese

- Young Dutch Man at a Window by Gerard Dou, returned to the Galleria Sabauda

Returned to Austria

- The Peasant and the Nest Robber by Peter Brueghel the Elder

- The Peasant Dance by Brueghel the Elder

Returned to Spain

- Immaculate Conception by Murillo. Taken in 1813 and exchanged in 1941 for Velázquez's Portrait of Mariana of Austria

Gallery of images

_-_n._047_-_Venezia_-_Cavalli_di_S._Marco.jpg.webp)

Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia, Raphael

Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia, Raphael_01.jpg.webp) Portrait of Tommaso Inghirami, Raphael

Portrait of Tommaso Inghirami, Raphael Madonna with the Long Neck, Parmigianino

Madonna with the Long Neck, Parmigianino

References

- L'arte conquistata : spoliazioni napoleoniche dalle chiese della legazione di Urbino e Pesaro. Modena: Artioli. 2003. ISBN 978-8877920881.

- Gilks, David (2013). "Attitiudes to the Displacement of Cultural Property in the Wars of the French Revolution and Napoleon". The Historical Journal. 56 (1): 113–143. doi:10.1017/S0018246X12000453. ISSN 0018-246X. JSTOR 23352218. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Steinman, E. (1917). "Die Plünderung Roms durch Bonaparte". Internationale Monatsschrift für Wissenschaft, Kunst und Technik. 11 (6/7): 1–46.

- Tosoni, Valentina (15 December 2016). "Tra Napoleone e Canova. Quelle opere che tornarono dal "Museo Universale"". la Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Hoeniger, Cathleen (11 April 2012). "The Art Requisitions by the French under Napoléon and the Detachment of Frescoes in Rome, with an Emphasis on Raphael". CeROArt (HS). doi:10.4000/ceroart.2367.

- Quynn, Dorothy Mackay (April 1945). "The Art Confiscations of the Napoleonic Wars". The American Historical Review. 50 (3): 437–460. doi:10.2307/1843116. JSTOR 1843116.

- Prieur, Cynthia. "Local art appropriation in France—a study of the loot in the Louvre Museum – Smarthistory". SmartHistory. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Goodwin, Paige S. (December 2008). "Mapping the Limits of Repatriable Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Stolen Flemish Art in French Museums". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 157 (2): 673–705. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Prieur, Cynthia. "Napoleon's appropriation of Italian cultural treasures". SmartHistory. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Grégoire. "Rapport sur les destructions opérées par le Vandalisme et les moyens de le réprimer". www2.assemblee-nationale.fr (in French). Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Lipkowitz, Elise S. (March 2014). "Seized natural-history collections and the redefinition of scientific cosmopolitanism in the era of the French Revolution". The British Journal for the History of Science. 47 (1): 15–41. doi:10.1017/S0007087413000010. ISSN 0007-0874. JSTOR 43820952. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Wescher, Paul (September 1964). "Vivant Denon and the Musée Napoléon". Apollo: The international magazine of arts (31): 178–186.

- Houpt, Simon (2006). Museum of the missing : a history of art theft. New York, NY: Sterling. pp. 32–34. ISBN 9781402728297.

- Albera, Marco (1997). I furti d'arte. Napoleone e la nascita del Louvre.

- Furet, François; Richet, Denis (2004). La Rivoluzione francese. Corriere della Sera. p. 439.

- Grew, Raymond (1999). "Finding Social Capital: The French Revolution in Italy". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 29 (3): 407–433. doi:10.1162/002219598551760. ISSN 0022-1953. JSTOR 207135. S2CID 143094454. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Casciu, Stefano. The Galleria Estense in Modena a brief guide. Modena: Franco Cosimo Panini. pp. 7–11, 13, 16–26, 80, 94. ISBN 978-88-570-0997-1.

- "Dispense sulle spoliazioni di Napoleone Bonaparte a Modena - Museologia a.a. 2011/2012". StuDocu (in Italian). Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- "Da Correggio a Guercino. Opere su carta in mostra a Modena". Panorama (in Italian). 26 February 2018.

- "I fogli pregiati dei duchi d'Este". www.ilgiornaledellarte.com.

- "La Francia nel 1816 restituisce a Parma due grandi tele asportate dalla nostra Cattedrale". IlPiacenza (in Italian). Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- "Medici Venus". Uffizi Gallerieswww.uffizi.it. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Restauro Filippo Lippi". web.archive.org (in Italian). 18 June 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Storia di Venezia: Venzia Ori e Argenti Fusi nel 1797" (PDF). Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Morosini, I. C. (2017–2018). "Chiese Scomparse e Soppresse a Venezia: Nell'Epoca Napoleonica" (PDF) (in Italian).

- Beltrame, Carlo. I cannoni di Venezia : artiglierie della Serenissima da fortezze e relitti. [Borgo San Lorenzo, Italy]. ISBN 978-88-7814-588-7.

- "Le Spoliazioni Napoleoniche e il Cannone Ancora "Prigioniero" a Parigi". Dal Veneto al Mondo. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Brignon, Arnaud (2019). "Les conditions d'acquistion de la collection Gazola de poissons fossiles du Monte Bolca (Éocène, Italie) par le Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "600 Fossili per Napoleone" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- "Dai tombaroli a Napoleone a Peruggia. L'arte di rubare arte". la Repubblica (in Italian). 17 September 2013.

- Wallace, Robert (1966). World of leonardo : 1452-1519. [Place of publication not identified]: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0316509206.

- Frigerio, Luca (21 February 2019). "All'Ambrosiana le meraviglie del Codice Atlantico". Chiesa di Milano (in Italian). Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Lee, Henry (1837). The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte: Down to the Peace of Tolentino and the Close of His First Campaign in Italy. T. and W. Boone. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- Macciocchi, Maria Antonietta. "Napoleone lo scippo d'Italia". archivio.corriere.it. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- Steinman, E. 1917.

- Stephens, H. Morse; Laborie, L. De Lanzac De (January 1898). "Souvenirs d'un Historien de Napoleon". The American Historical Review. 3 (2): 360. doi:10.2307/1832517. JSTOR 1832517.

- Gotteri, Nicole (1995). Enlèvements et restitutions des tableaux de la galerie des rois de Sardaigne (1798-1816). dans Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. pp. 459–481.

- The table is entitled "Notice des tableaux envoyés d'Italie en France par les commissaires du Gouvernement français." de Brosses, Charles. Lettres historiques et critiques sur l'Italie. Paris: chez Ponthieu. pp. 387–411.

- Auber (1802). Collection complète des tableaux historiques de la Révolution française. Paris: Pierre Didot l’aîné. pp. pl. 136.

- Jordan, Tristan (2011). "Le dossier Edmond de Goncourt dans les Archives de la Préfecture de police de Paris". Cahiers Edmond et Jules de Goncourt. 1 (18): 155–158. doi:10.3406/cejdg.2011.1061.

- Prévost (1777). Histoire générale des voyages ou Nouvelle collection de toutes les relations de voyages par mer et par terre, qui ont été publiées jusqu'à présent dans les différentes langues de toutes les nations co contenant ce qu'il y a de plus remarquable, de plus utile, & de mieux avéré, dans les pays où les voyageurs ont pénétré, touchant leur situation, leur étendue, leurs limites ... : avec les moeurs et l (in French). Chez E. van Harrevelt & D.J. Changuion. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.46698.

- Eustace, Katharine (1 June 2015). "The fruits of war: how Napoleon's looted art found its way home". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- Brooks, Peter (November 19, 2009). "Napoleon's Eye". The New York Review. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Kino, Carol (28 July 2003). "Who owns looted art?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Romano, Sergio (27 July 2014). "Il ritorno dell'arte perduta. Canova a Parigi nel 1815". Corriere della Sera.

- Saunier, Jean de.; Saunier, Jean de; Saunier, Gaspard de; Moetjens, Adrian (1734). "La parfaite connoissance des chevaux : leur anatomie, leurs bonnes & mauvaises qualitez, leurs maladies & les remedes qui y conviennent". Chez Adrien Moetjens, libraire. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.155833. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - 8 Denon to Talleyrand, quoted in Saunier, p. 114; Muintz, in Nouvelle Rev., CVII, 2OI.

- Scarisbrick, Diana (5 November 2007). "Life at Malmaison". Apollo Magazine. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- De Clementi, Andreina (2011). Genre, femmes, histoire en Europe : France, Italie, Espagne, Autriche. [Nanterre]: Presses universitaires de Paris Ouest. pp. 297–312. ISBN 978-2-84016-100-4.

- Johns, Christopher M. S. (1998). Antonio Canova and the politics of patronage in revolutionary and Napoleonic Europe. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21201-5.

- Siegel, Jonah (2010). "Owning Art after Napoléon: Destiny or Destination at the Birth of the Museum". PMLA. 125 (1): 142–151. ISSN 0030-8129. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- Wescher, Paul (1978). Kunstraub unter Napoleon (in German). Berlin: Mann.

- Hoock, Holger (2010). ""Struggling against a Vulgar Prejudice": Patriotism and the Collecting of British Art at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century". Journal of British Studies. 49 (3): 566–591. ISSN 0021-9371. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "15 importanti opere d'arte che si trovano all'estero e che l'Italia gradirebbe tornassero indietro". www.finestresullarte.info (in Italian).

- Edwardes, Charlotte; Milner, Catherine (20 July 2003). "Egypt demands return of the Rosetta Stone". The Telegraph. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Bailey, Martin (6 December 2019). "Archaeologist launches private bid to retrieve priceless Egyptian treasures from European museums". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Dispense sulle spoliazioni di Napoleone Bonaparte a Modena - Museologia a.a. 2011/2012". StuDocu (in Italian). Retrieved 26 December 2020.

Bibliography

- Mazzaferro, Francesco. "On the Ashes of Kings: The biggest plunder of history". Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- "Fondazione Maria Cosway: The Artist". www.fondazionemariacosway.it. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- Wescher, Paul (September 1964). "Vivant Denon and the Musée Napoléon". Apollo: The international magazine of arts (31): 178–86. ISSN 0003-6536.

- "Antonio Canova e il recupero delle opere". Repubblica@SCUOLA (in Italian). Repubblica@SCUOLA.