Tonlé Sap

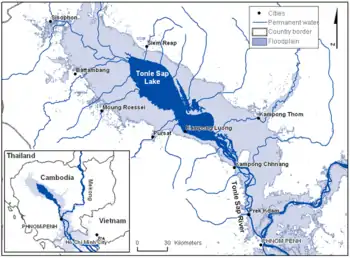

Tonlé Sap (Khmer: ទន្លេសាប IPA: [tunleː saːp], literally large river (tonle); fresh, not salty (sap), commonly translated to 'great lake') is a seasonally inundated freshwater lake, the Tonlé Sap Lake and an attached river, the 120 km (75 mi) long Tonlé Sap River, that connects the lake to the Mekong River.[1] They form the central part of a complex hydrological system, in the 12,876 km2 (4,971 sq mi) Cambodian floodplain covered with a mosaic of natural and agricultural habitats that the Mekong replenishes with water and sediments annually. The central plain formation is the result of millions of years of Mekong alluvial deposition and discharge. From a geological perspective, the Tonlé Sap Lake and Tonlé Sap River are a current freeze-frame representation of the slowly but continuously shifting lower Mekong basin. Annual fluctuation of the Mekong's water volume, supplemented by the Asian monsoon regime, causes a unique[2] flow reversal of the Tonle Sap River.[3] The largest freshwater lake in Southeast Asia, it contains an exceptional large variety of interconnected eco-regions with a high degree of biodiversity and is therefore a biodiversity hotspot. It was designated a UNESCO biosphere reserve in 1997.[4]

| Tonlé Sap | |

|---|---|

NASA satellite image | |

Tonlé Sap  Tonlé Sap | |

| Location | Lower Mekong Basin |

| Coordinates | 12°53′N 104°04′E |

| Type | alluvial |

| Primary inflows | Tonle Sap River, Siem Reap River |

| Primary outflows | Tonle Sap River |

| Basin countries | Cambodia |

| Max. length | 250 km (160 mi) (maximum) |

| Max. width | 100 km (62 mi)(maximum) |

| Surface area | 2,700 km2 (1,000 sq mi) (minimum) 16,000 km2 (6,200 sq mi) (maximum) |

| Average depth | 1 m (3.3 ft) (minimum) |

| Max. depth | 10 m (33 ft) |

| Water volume | 80 km3 (19 cu mi) (maximum) |

| Surface elevation | 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) |

| Settlements | Siem Reap, Battambang |

The Tonlé Sap Lake occupies a geological depression (the lowest lying area) of the vast alluvial and lacustrine floodplain in the lower Mekong basin, which has been induced by the collision of the Indian Plate with the Eurasian Plate.[5][6] The lake's size, length and water volume varies considerably over the course of a year from an area of around 2,500 km2 (965 sq mi), a volume of 1 km3 (0.24 cu mi) and a length of 160 km (99 mi) at the end of the dry season in late-April to an area of up to 16,000 km2 (6,178 sq mi), a volume of 80 km3 (19 cu mi) and a length of 250 km (160 mi) as the Mekong maximum and the peak of the southwest monsoon's precipitation culminate in September and early-October.[7]

As one of the world's most varied and productive ecosystems the region has always been of central importance for Cambodia's food supply. It proved capable of largely maintaining the Angkorian civilization, the largest pre-industrial settlement complex in world history.[8] Directly and indirectly it affects the livelihood of large numbers of a predominantly rural population.

The lake and its surrounding ecosystems have come under increasing pressure from deforestation, infrastructure development and climate change in recent years.[9][10][11] All Mekong riparian states have constructed a series of dams to exploit the river's hydroelectric potential. A succession of international facilities that dam the river's mainstream is thought to be a serious threat to the Tonle Sap eco-region by reducing flow into the lake and reducing connectivity.[12] Climate change caused a number of severe droughts in Cambodia during the 2010s, which has further affected the annual river flow into the lake. Fisheries and food security of the population have been affected.[13][14] Satellite imaging suggested the low water levels during 2019 was driven by a particular severe drought and was exacerbated by the withholding of water in hydropower dams in China.[15]

Overview

| Greater Mekong Subregion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mekong River Basin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Upper Mekong Basin (UMB) | Lower Mekong Basin (LMB) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Northern Highlands | Annamite Range | Southern Uplands | Khorat Plateau | Cambodian Floodplain – Great Lake Ecosystem | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cultivated Lands | Deciduous Forests | Wetlands | Tonle Sap River | Tonle Sap Lake | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Swamps and Marshes | Aquatic Habitats | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lower Mekong basin

The lower Mekong basin (LMB) encompasses the lower half of the Mekong River's length of 2,600 km (1,600 mi) and the surrounding drainage basin of around 607,000 km2 (234,000 sq mi). It is divided into five distinct physiographic units: the northern highlands; the Annamite chain; the southern uplands; the Korat Plateau; and the Mekong plain. These regions each have distinct geology, climate, vegetation and human-use patterns.

The lower Mekong basin rests on an ancient block of continental crust that has remained relatively stable since the Jurassic Period, a period of over 150 million years. Large areas were covered by an inland sea during the upper Mesozoic Era, during which thick red-bed sandstones and evaporites were deposited.

The Sekong, Sesan, and Srepok Rivers—collectively called the 3S Basin—are the dominant tributaries. All three enter the Mekong on the eastern bank. At the southern end of the basin, the mainstream breaks up into a complex network of branching and reconnecting channels. One of these branches forms the Tonle Sap River. The western and central parts of the southern basin make up the great lake.[16]

The lower Mekong basin experiences two monsoon periods: rain from May to October and a dry season from November to March. The annual rainfall is between 1,000 and 3,000 mm, locally up to 4,000 mm, falling almost entirely during the rainy season.[17] Water levels reach their highest in September and October.[18]

The Great Lake ecosystem

Cambodian floodplain

The Cambodian floodplain or the Mekong Plain is a vast low-lying area traversed by the Mekong River. Only a relatively small portion of the plain consists of fluviatile deposits of the young Mekong. The plain encompasses most of lowland Cambodia and the Mekong delta of Vietnam, a small part of southern Laos, and a small part of eastern Thailand in Chantaburi and Prachinburi Provinces. It is bordered by the Dangrek Mountains on the north, the Elephant and Cardomom mountains on the south, and the southern Annamite Range on the east. The plain is about 800 kilometers from north to south and 600 kilometers from east to west. It is mostly less than 100 meters in elevation, but a few higher outcroppings are scattered throughout the plain and much of northern Cambodia is characterized by rolling and dissected plains between 100 and 200 meters elevation. The plain is the result of erosion and sedimentation. The sediments vary in depth from at least 500 meters near the mouth of the Mekong to only about 30 meters at Phnom Penh, with bedrock outcroppings in isolated hills above the plain in several places.[19]

The Tonle Sap is the largest freshwater lake in Southeast Asia and one of the richest inland fishing grounds in the world. The lake functions as a natural flood water reservoir for the Mekong system as a whole by regulating the floods downstream from Phnom Penh during the wet season and makes an important supplement to the dry season flow to the Mekong delta.[20]

Wetlands, flooded forests, and deciduous forests

A belt of freshwater mangroves known as the "flooded forest" surrounds the lake. The floodplains in turn are surrounded by low hills, covered with evergreen or deciduous seasonal tropical forest dominated by species of Dipterocarpaceae, Leguminosae, Lythraceae, Fagaceae and in some places Pinaceae, Podocarpaceae, or bamboo.[21] The eco-region consists of a mosaic of habitats for a great number of species.[22] The forest gradually yields to bushes and finally grassland with increasing distance from the lake. On higher quality soils or at higher elevation, areas of mixed deciduous forest and semi-evergreen forests occur.[23] This variety of vegetation types accounts for the quantity and diversity of species of the Great Lake ecosystem. Interlocking forest, grassland, and marshland patches provide refuge for the local wildlife.[24][25]

The lake's flooded forest and the surrounding floodplains are of utmost importance for Cambodia's agriculture as the region represents the cultural heart of Cambodia, the center of the national freshwater fishery industry, the nation's primary protein source.[26]

Threats to the lake include widespread pollution, stress through growth of the local population which is dependent on the lake for subsistence and livelihood, over-harvesting of fish and other aquatic, often endangered, species, habitat destruction, and potential changes in the hydrology, such as the construction and operation of dams, that disrupt the lake's natural flood cycle. However, concerns that the lake is rapidly filling with sediment seem[27] to be unfounded at the present time.[28]

Volume fluctuation and flow reversal

Inflow starts in May or June with maximum rates of flow of around 10,000 m3/s (350,000 cu ft/s) by late-August and ends in October or November, amplified by precipitation of the annual monsoon. In November the lake reaches its maximum size. The annual monsoon coincides to cease around this time of the year. As the Mekong River is at its minimum flow around this time of the year and its water level falls deeper than the Tonle Sap Lake, the Tonle Sap River and surrounding wetlands, waters of the lake's basin drains via the Tonle Sap River into the Mekong. As a result, the 115-kilometre-long (71 mi) Tonle Sap River flows six months a year from southeast (Mekong) to northwest (lake) and six months a year in the opposite direction. The mean annual reverse flow volume in the Tonle Sap is 30 km3 (7.2 cu mi), or about half of the maximum lake volume. A further 10 percent is estimated to enter the system by overland flow from the Mekong.[29][30] The Mekong branches off into several arms near Phnom Penh and reaches Vietnamese territory south of Koh Thom and Loek Daek Districts of Kandal Province.

There is extreme hydrodynamic complexity in both time and space and it becomes impossible to measure channel discharge. Water levels, not flow rates and volumes, determine the movement of water across the landscape.[31]

Sedimentation

Although the large amount of sediment in the Tonlé Sap Lake basin is a natural phenomenon, rapid rates of development and resource exploitation has focused the attention of observers who fear the basin is in danger of filling with sediment. These fears were first reported by local people who noticed some areas becoming shallower. With increased sedimentation, already vague transit routes between capital and regional centers would likely be shut down altogether and could restrict the migration of fish into the lake.

Because sediment contains nutrients that fuel food webs, the Tonlé Sap benefits from the influx. Sediment-bound phosphorus serves as food for phytoplankton through higher plants, and research has shown that the metabolizing of the chemical contributes to food abundance and quality. Internal nutrient cycling, therefore, plays an essential role in productivity of a floodplain.[32] The nutrients bound to suspended sediments are important for the Tonle Sap system, particularly its long-term sustainability.[33]

The reversal of the Tonlé Sap River's flow also acts as a safety valve to prevent flooding further downstream. During the dry season (December to April) Tonlé Sap Lake provides around 50 percent of the flow to the Mekong Delta in Vietnam.

The lake occupies a depression created due to the geological stress induced by the collision of the Indian subcontinent with Asia. In recent years, there have been concerns from scientists about the building of high dams and other changed hydrological parameters in southern China and Laos that has threatened the strength and volume of the reverse flow into Tonle Sap, which in turn decreases nesting, breeding, spawning, and feeding habitats in the floodplain, which results in adverse impacts on fish productivity and overall biodiversity.[34]

Fishing

Fishery management system

The 1987 fiat fishery law is still in force. Many of the regulations are largely based on colonial legislation. The fisheries of Cambodia can be divided in two broad categories: limited and open-access fisheries.

The most productive part of the Cambodian fisheries has been privatized for more than a century through a system of government leases on fishing lots. The rest is open-access. In the recent past, the lot system provided over US$2 million annually in tax revenues and more in an informal way. Open-access fisheries do not contribute to the public treasury.[35]

When the Tonlé Sap floods, the surrounding areas become a prime breeding ground for fish. During this time, fishers are scarce. Fishing during this period is illegal, to prevent disruption of mating. At the end of the rainy season, when the water levels go down, fishing is allowed again. Fishermen install floating houses along one half of the river, and the other half is left open for navigation.

Most of the fishing captains are of Vietnamese origin, and they are primary suppliers to the country's markets. Fisherman Sakaloy explains, "My parents were fishermen. We have lived in Cambodia and have this activity for a long time. We started well before the Pol Pot era, when the Khmer Rouge took over from 1975 to 1979. We had to flee to Vietnam, [but] afterwards we came back and have been fishing on the Tonlé Sap ever since." Thousands of peasants follow this lifestyle.[36]

Catching Tonlé Sap fish is simple. Later, the real work begins. Because of the drop in the water level, the Tonlé Sap naturally carries away thousands of fish. Fishers place cone-shaped nets into the water from their floating houses and then lift the net as soon as seconds later. Using this technique, two or three tons of fish are trapped each time and more than ten thousand tons of fish can be caught in under a week. One by one, fishers, mostly women, cut off the fish heads then take the fish back to the river to be cleaned and to remove the fat. Salting the fish for preservation is the final step in this process, but the fish will continue to macerate for several months in order to become a paste called prahok, a condiment that complements almost any dish. On average, three days of fishing supply enough prahok for an entire year.[37]

Fishers use all parts of the fish for their own needs and also for profit. Fish heads are dried in the sun, becoming a good fertilizer. By boiling the fat from the bottom of the fish basket, fishermen make soap for their own use. Through bartering on the banks, they exchange fish for rice. Excess rice is sold for profit. Despite paying employees and buying an official fishing license, fishermen still "have enough money to feed a family for a year. So I don't need rice fields." To further emphasize the importance of fish in the local economy, the name of Cambodian currency is "riel", the name of a small silver carp that is the staple of most diets.

Because of the Buddhist prescriptions against taking a life, Cambodians tend to limit fishing to the amount necessary to feed their families. To further lessen their guilt, fishermen do not physically kill fish. Instead they wait for the fish to die naturally when taken out of the water. Even so, fishers go to temple after the fishing season for purification.[36]

Cultivated lands and rice

The beginning of the dry season is also the beginning of rice season, which is the only source of wealth for peasants. A good harvest will provide enough rice for them to survive for the entire year, but if the floods are too big or too small, rice can become scarce. Because of this uncontrollable instability, many celebrations are held in honor of gods and genies that can influence nature and bring about a good harvest.

Historical research has shown that the old Angkorian civilization took advantage of the weather conditions by digging huge reservoirs during the wet season and releasing the water during the dry season using an irrigation system and the land’s natural slope. This double and sometimes even tripled the amount of rice crops per year, strengthening the developing nation. However, today, this irrigation network is no longer present, and peasants only get one rice crop a year. What has not changed is the planting of rice in fields as well as the survival value of rice. It is still the main source of income for peasants and the only currency used to bargain. They use the crops to pay for what they need, such as property rent for land to plant, and the rest is kept for the family to eat.

.jpg.webp)

At the end of the rice season, villagers celebrate by marching in a procession to the temple. This is a chance for everyone to relax after the long labor of the harvest season. As well, it provides an opportunity to have fun and bond with the community. All the villagers wear their nicest clothes, musicians sing and dance, and men take the opportunity to court young women. Upon arrival, believers circle the temple three times and then proceed to present gifts such as clothing, dishes, furniture, and food. These donations, named Kathen by Buddha, provide help for bhikkus, who in turn give blessings. This act of donation is essential in accumulating good karma for reincarnation, so eventually to reach Nirvana, or ultimate salvation, as well as for future harvests.[36]

Species diversity

The lake is home to at least 149 species of fish, eleven globally threatened species, and six near-threatened species.[28] These threatened and near-threatened species include the spot-billed pelican, greater adjutant, Bengal florican, Oriental darter, grey-headed fish eagle, and the Manchurian reed warbler. Specifically, the large colonies of unique birds constitute the Preak Toal Bird sanctuary. In addition, the Tonlé sap also supports significant reptile populations including nearly extinct Siamese crocodiles and a large number of freshwater snakes. Although the area around the lake has been modified for settlement and farming, about 200 species of plants have been recorded.[28]

One of the most legendary species living in the Tonlé sap is the Mekong giant catfish, one of the largest freshwater fish in the world. The fish is 2.4 to 3.0 metres (8 to 10 ft) long and can weigh anywhere between 110 and 230 kilograms (250 and 500 lb). The largest of these catfish ever caught weighed 306 kilograms (674 lb). Despite its massive physical characteristics, the Mekong catfish is especially vulnerable to chemical changes, which is beneficial in alerting authorities of trouble in the river ecosystem early on. The population of these fish has been steadily declining since the Khmer Rouge era, led by Pol Pot, and in 2005, fisherman reported that on average only one giant catfish was caught per day. Currently, it is illegal for fishermen to catch and keep these fish with the exception of a few retained by fisheries for research. It also cannot be used in any form of trade in fear of the economic exploitation.[38]

Tonlé Sap Biosphere Reserve

In 1997, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, deemed Tonlé Sap an ecological hotspot. As a result, in 2001, by royal Decree issued by the government of Cambodia, the lake and its surrounding provinces became the Tonlé Sap Biosphere Reserve. There are nine provinces that are part of the Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve. These are Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, Kampong Chhnang, Kampong Thom, Preah Vihear, Pursat, Siem Reap, Oddar Meanchey and Pailin.[39]

The Cambodian government takes responsibility for the fulfillment of three functions:

- a) a conservation function to contribute to the protection of biological diversity, landscapes, and ecosystem, including genetic resources, plant, fishery and animal species, and to the restoration of the essential character of the environment and habitat of biodiversity;

- b) a development function to foster sustainable development of ecology, environment, economy, society, and culture;

- c) a logistic function to provide support for demonstration projects, environmental education and training, research and monitoring of environment related to the local, national and global issues of conservation and sustainable development.

Additionally, the Tonlé Sap Biosphere Reserve established three zones: a core zone, a buffer zone, and a transition zone. Formally, the core area of a Biosphere Reserve is defined as an area devoted to biological resources, landscapes, and ecosystems. The core zone includes practices that protect sites for conserving biodiversity, monitoring minimally disturbed ecosystems and undertaking non-destructive research and related activities. As of today, the three zones are Prek Toal, Boeng Chhmar, and Stung Sen.[40]

Despite this government protection, illegal fishing, poaching, and cutting of the forest for farmland are all still major problems. Because people living around the lake are extremely poor and depend on the lake for their survival, it is likely that this unsustainable living will continue. During recent years, the amount of fish caught has been steadily declining, which means peasants must also work harder to provide for their families. The government is working on supporting and educating these people to break this cycle of poverty and non-sustainability. Finding a balance between survival and conservation seems to be the major question for the future.[41]

Cultural significance

Celebration of the Seven-Headed snake

This celebration also goes by the name Water and Moon Festival and was established to mark the reversal of the Tonlé sap and open the fishing season. The festival lasts three days and begins on the last day of the full moon. However, because of the variation of the monsoon seasons, the reversal of the river does not always coincide exactly with the festival. In the simplest form, the celebration is a series of canoe races, including some 375 teams, and victory brings good fortune for the coming fishing season for the entire village. In addition, these water celebrations are a tribute to a tooth lost in the depths by a nāga whose daughter married a Buddhist Indian prince to establish the kingdom of Cambodia. According to legend, when he was cremated, his tooth fell into the river down to the nāga kingdom.

In pagodas along the river, men prepare for the festival by either restoring sacred canoes that have existed for hundreds of years or building new canoes when the old ones are beyond repair. Canoes are made from one piece of a trunk of a coki tree; the wood of the coki tree is resistant to rotting. Each canoe is painted with patterns and eyes that symbolize the guardian goddess, often the spirit of a young tillage girl. This is a modification from the superstitious tradition of sacrifice of nailing actual eyes to the boat dating back before Buddhism. The morning after completion and after three sacred shouts by the crew, the canoes are pushed into the river and head for the capital at full moon. Some crews must row for hours, and others will row for several days. Being chosen as a member of the crew is one of a man’s highest honors, and members must practice to perfect team coordination. Only the best crews will get to the finals in the capital.

After two days of racing, all of the canoes come together to encourage the nāga to spit out the swelling waters of the Tonlé sap towards the sea. Firecrackers light the water, the royal palace, and the sky. This moment lets the legendary snake master of water know to return to the depths of the Tonlé sap and leave the power to the sun gods. This also marks the end of the rainy season.[36]

The area is home to many ethnic Vietnamese and numerous Cham communities, living in floating villages around the lake. Approximately 1.2 million people living in the greater Tonle sap make their living by fishing on the local waters. Cambodia produces about 400,000 tonnes of freshwater fish per year, the majority of which comes from Tonle sap. These fisheries account for 16 percent of national GDP, making the fish industry not only essential to the diet of local populations but to the Cambodian economy as a whole.[35]

During more than five months of the year, the great lake of Cambodia, Touli-Sap, covers an immense space of ground: after that period there is a diminution in depth owing to the great evaporation, but its width remains nearly unaltered. Although its waters increase in volume during the rainy season, these are not swelled by the streams from the mountains on its western boundary, but by the strength of the current from the Mekon which pours into it its overflow.[sic]—Henri Mouhot (1864)[42]

Floating basketball court

Floating basketball court Floating church

Floating church Boat from Phnom Penh to Siem Reap

Boat from Phnom Penh to Siem Reap Boy on a boat holding a tame python about his neck.

Boy on a boat holding a tame python about his neck.

See also

References

- Seiff, Abby (2017-12-29). "When There Are No More Fish". Eater. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Agnes Alpuerto (November 16, 2018). "When the river flows backwards". Khmer Times. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- Arias, Mauricio Eduardo. "Impacts of Hydrological Alterations in the Mekong Basin to the Tonle Sap Ecosystem". Christchurch NZ: University of Canterbury. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- "Conservation Project of the Century". Miami Herald. July 13, 1997.

- Tjia, H. D. (2014-04-28). "Wrench-Slip Reversals and Structural Inversions: Cenozoic Slide-Rule Tectonics in Sundaland". Indonesian Journal on Geoscience. Institute for Environment and Development University Kebangsaan Malaysia. 1 (1): 35–52. doi:10.17014/ijog.v1i1.174.

- "Petroleum Geology of the Gulf of Thailand – Gulf of Thailand Basins – Regional Overview p.2". Greg Croft Inc. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- "Overview of the Hydrology of the Mekong Basin". Mekong River Commission. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- Thung, Heng L (1994). "Geohydrology and the Decline of Angkor" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 82 (1): 9–14. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "An Introduction to Cambodia's Inland Fisheries" (PDF). Mekong River Commission. November 2004. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- Seiff, Abby (2019-09-30). "Opinion | At a Cambodian Lake, a Climate Crisis Unfolds (Published 2019)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- Piman, Thanapon (2019-03-25). "Assessing Climate Change Impacts on River Flows in the Tonle Sap Lake Basin, Cambodia". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Goichot, Marc (May 6, 2015). "Multiple dams are an ominous threat to life on the Mekong River". The Guardian. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- Osborne, Zoe (2019-12-16). "Mekong basin's vanishing fish signal tough times ahead in Cambodia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- @NatGeoUK (2020-08-17). "Cambodia's biggest lake is running dry, taking forests and fish with it". National Geographic. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- "New Evidence: How China Turned Off the Tap on the Mekong River • Stimson Center". Stimson Center. 2020-04-13. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- "Physiographic Regions". Mekong River Commission. n.d. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- McElwee, Pamela; Horowitz, Michael M (1999). Environment and Society in the Lower Mekong Basin: A Landscaping Review (PDF). Binghamton: Institute for Development Anthropology, SUNY. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "Chapter 1 Geology and Physiographic Units". International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- "Agriculture in the Lower Mekong Basin Chapter 1 Geology and Physiographic Units". IUCN. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- Chadwick, M T; Juntopas, M; Sithirith, M (2008). Sustaining Tonle Sap: An Assessment of Development Challenges Facing the Great Lake. Bangkok: The Sustainable Mekong Research Network. ISBN 9789186125066.

- "A. Flora of Cambodia" (PDF). Cambodia Tree Seed Project. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- "Dipterocarpaceae Data Base". Forestry Research Programme. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- "semi-evergreen seasonal tropical forest". Encyclopedia com. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- Hydrology. Mekong River Commission. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- "Dry Forest Ecology". World Wide Fund For Nature. Archived from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- CASE STUDY No. 3: TRADITIONAL USE AND AVAILABILITY OF AQUATIC BIODIVERSITY IN RICE-BASED ECOSYSTEMS. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- "Sediment: Curse or Blessing for Tonle Sap Lake" (PDF). Aalto University. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- Campbell, Ian C; Poole, Colin; Giesen, Wim; Valbo-Jorgensen, John (October 2006). "Species diversity and ecology of Tonle Sap Great Lake, Cambodia". Aquatic Sciences. 68 (3): 355–373. doi:10.1007/s00027-006-0855-0.

- "Tonle Sap Cambodia – River Lake". Tonle Sap. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- "Cambodia; 1.4. Hydrology". Water Environment Partnership in Asia (WEPA). Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- Overview of the Hydrology of the Mekong Basin (PDF). Vientiane: Mekong River Commission. November 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- Kummu, Matti; Dan Penny; Juha Sarkkula; Jorma Koponen (May 2008). "Sediment: Curse or Blessing for Tonle Sap Lake?". Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. 37 (3): 158–162.

- Sediment: Curse or Blessing for Tonle Sap Lake? Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Technical Note 10" (PDF). Impacts on the Tonle Sap Ecosystem. Mekong River Commission. June 2010. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Van Zalinge, Nicolaas. "Data Requirements for Fisheries Management in the Tonle Sap". FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. UN FAO. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Children of the Seven-Headed Snake. Dir. Didier Fassio. Perf. Didier Fassio. Film Makers Library, 2002. Film.

- Regional Office for Asia and Pacific. "Tonle Sap Fisheries". FAO. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- Sullivan, Michael (12 July 2005). "Tonle Sap: The Flowing Heart of Cambodia". NPR. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve". UNESCO OFFICE IN PHNOM PENH. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

- "Strategic Management for the Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve Conservation & Protection" (PDF). UNWTO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-23. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

- Wildlife Conservation Society. "The Tonle Sap Biosphere Reserve". Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- Mouhot, Henri (1864). Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos During the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860 (Vol. 1 of 2). Retrieved 4 January 2018.

Further reading

- Kuenzer, C. (2013): "Field Note: Threatening Tonle Sap: Challenges for Southeast-Asia’s largest Freshwater Lake." In: Pacific Geographies 40, pp. 29–31.

- Milton Osborne, The Mekong, Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2000) ISBN 0-87113-806-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tonle Sap. |

- CPWF-Mekong

- 3S Rivers Protection Network

- Australian Mekong Resource Centre

- Cambodia National Mekong Committee

- THE STRATEGIC SIGNIFICANCE OF THE MEKONG By: Osborne, Milton

- Washington Post

- Country Profile

- International Journal of Water Resources Development – Tonle Sap Special Issue

- Tonle Sap Modelling project (WUP-FIN) under Mekong River Commission

- Protected areas in Cambodia