Tourism in Réunion

Tourism is an important part of the economy of Réunion, an island and French overseas departement in the Indian Ocean. Despite its many tourism assets, the island's tourist attractions are not well known.

History

The discovery of the island

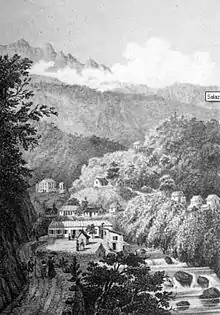

The island has been inhabited since the 17th century. As a stop on the route des Indes, it was visited by sailors, diplomats and explorers. It was also popular with naturalists such as Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent. It was almost by accident that Charles Baudelaire stayed there for several weeks in 1841. Difficult to reach before the advent of commercial flight, it took a long time before being featuring on the tourist circuit. Travel was also difficult on the island itself. Before the Réunion railway was built in 1882, it took two days to cross the island from Saint-Denis to Saint-Pierre.[1] Only intrepid hikers made the several-day expedition to see the active volcano Piton de la Fournaise.[2] Creole families from the west explored the more accessible (but still wild) sites such as Bernica and the Saint-Gilles Ravine, as recorded in the poems of Leconte de Lisle.[3] The painter Antoine Roussin published L'Album de l'île as a series of installments in 1857. He was Réunionese by adoption and these paintings gave an idea of the landscape and the most popular sites on the island during the second half of the 19th century.

The rise of thermalism in the 19th century set off a some tourist activity among customers looking for relaxation. The spa clients stayed in the elegant Hell-Bourg station, and also in Cilaos after 1882.[4] Access difficulties and the lack of infrastructure stopped a third location, Mafate-les-eaux, from exploiting its thermal potential in the same way.

Until the first half of the 20th century, the economy depended on sugar cane. Réunion became a French department in 1946.

From becoming a department until the 1990s

Contact with mainland France increased, with the arrival of functionaries in Réunion, and many of the local populace moving to the mainland to search for work. By the end of World War II, flights operated between France and Réunion every three days.

In 1963, Réunion received 3000 visitors,[5] who stayed in its four tourist hotels. The first Boeing 707 left Gillot airport in 1967. Despite these changes, the island remained less popular with tourists than other destinations, and in particular received fewer tourists than the other overseas departments.[6] This was partly due to Air France's (and Air Madagascar's) monopoly of flights to the island. Other organisations started to get involved, including Club Med in the first half of the 1970s and Novotel in 1976. But it took the deregulation of air traffic (between 1983 and 1986) and the end of Air France's monopoly (allowing Union de Transports Aériens[7]) for tourism to start to develop spontaneously. The island gained a specific body for tourism in 1989. It was called the Réunion Tourism Committee (the CTR).[6] Tourism truly developed during the 1990s and became one of the island's important economic resources.[8]

1990–2004: the big tourist boom

Tourism started to develop beyond anything previously known in Réunion. A second airport, Pierrefonds near Saint-Pierre, opened to commercial traffic in 1998.[9] In January of that year the Observatoire du développement de La Réunion noted that the general public were still sensitive to the development of the new sector, although it created many new jobs on the island.[10] Tourism brought 370,000 visitors to the Intense Island (as it had been named by the CTR), with a turnover of 1.7 million francs.[11]

In 2000, the turnover from tourism overtook that of the local sugar industry. The authorities were confronted with new problems: land management, and the effect of tourism on local culture.

Initiatives answering that question began to multiply, such as the start of villa holidays in the west of the island.[12] In 2001, several communes elaborated on the concept of creole village, celebrating the diversity of Réunion heritage. Fifteen villages sought to highlight their individuality. For Bourg-Murat, this meant life at the door of the volcano; for Entre-Deux it was Creole huts and houses.[13] The island started to publish a list of top-quality establishments in 1995 to rewarded the best providers of accommodation and catering.[14] By 2002, the list included 70 different establishments.[15] The emphasis was on marketing, the idea being to increase tourism it was important to publicise Réunion and show the world a positive image.

The 10 years of effort yielded fruit: Réunion had 426,000 tourists in 2002[16] and was the fifth most popular destination for tourists from the French mainland.[17] The regions of the island did not develop equally – tourism mostly benefited the north and the beaches to the west. Their success encouraged other communes who had previously been more concerned about the new sector, for example Saint-Louis and Sainte-Suzanne, which began initiatives to attract both internal and external tourists.[18][19] The French government also intervened to support overseas tourism, by launching a campaign in 2003 called << France of the three oceans >>,[20] and the Insee saw a growth in tourism to Réunion despite international tensions affecting air traffic in general.[21] A new airline opened, Air Bourbon, funded partly by Réunion capital, and made its first flights between the island and the mainland after a rough start.

Consideration was also given to the impact of tourism, particularly internal tourism. This was also growing quickly, with the construction of new recreational areas, hiking trails and picnic areas. This was damaging natural sites in an unanticipated way.[22] But globally, the mood was optimistic and the island published a text Schéma de développement touristique de La Réunion in 2004. That year, they received 430,000 external tourists and generated 6,000 jobs in the sector, providing 6.5% of the total salary for all workers.[23] · [24]

Also in 2004, the CTR launched an initiative to intensively promote gay tourism by featuring the island at the Salon rainbow Attitude, the European gay expo. CTR opened a website as part of their effort to increase online tourist marketing.[25]

In January 2005 the responsibility for tourism was transferred to the region itself.[26] In March of that year, the council proposed the ambitious goal of exceeding a million tourists in 2020.[27] They proposed a series of measures, notably adapting the accommodation for disabled people,[28] and to ride the new wave of well-off tourists, particularly senior citizens.[29] In October 2005, Réunion was the sixth most popular overseas department for tourists.[30] They formed a partnership with the sister island of Mauritius to promote the Mascarene Islands as a tourist destination.[31]

The clientele are distinguished from tourists to other places by the high number of affinity tourists. An affinity tourist is someone who goes on holiday to stay with friends or family who already live in the destination.

2005–2006: The crisis

The first indication of the crisis appeared in 2005 when the numbers started to show a decline in the tourist sector. According to Insee figures, the decline got stronger and stronger.[32] The crisis was global and affected the other French overseas departments too, but Réunion attributed it to a marketing failure.[33] A series of mishaps contributed to a damaged image of Réunion as a destination. At the end of 2004, Air Bourbon went into liquidation, which left travellers on the island without a flight home. 7000 customers failed to get a refund for their tickets. In August 2005, Brigitte Bardot wrote to the head of Réunion to complain about the "dogs as shark bait" scandal, which had caused a media storm.[34][35] Also, the Chikungunya epidemic, which started at the end of 2005, reached a peak in January 2006.

These all dissuaded people from visiting the island and receipts from tourism fell by 27% and employment declined in the hotel industry.[36] The CTR blamed the drop in tourism on the epidemic,[37] in addition to the negative image that the island had suffered in the media.[38] There had also been media exaggeration of the risk of shark attacks around the island, and of the risk of links to the Asian SARS outbreak.[38]

Believing the crisis to be cyclical, the CTR relaunched an information campaign, while the local tourism employers turned to the mainland for support. Three months later, barely 3 million of the expected 60 million had reached their intended recipients. Large groups with international stature, such as Bourbon and Accor, were excluded from state support due to European regulations. Small, local, businesses struggled to compile the right documentation. The Villepin government celebrated it as 4.5 million to relaunch tourism. A plan to relaunch Réunion as a destination was announced in September 2005. This campaign was launched from the City Hall steps in Paris, at the invitation of the mayor, Bertrand Delanoë. They hoped this would relaunch the destination with the mainlanders and Réunion expatriates, and seduce foreign tourists with the Creole village punch and samosas. The campaign was publicised by the written media, television and the internet. The CTR were assigned a budget of 800,000 Euros to publicise Réunion better in Germany, Belgium and Switzerland.

At the same time, the Prime Minister told the agency Odit France to compile a report analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of tourism in Réunion.

At the end of 2006, the Journal de l'île published an article claiming that the problems being discussed were in fact masking the underlying structural problems.

Improvements since 2014 onwards: European Tourism

In 2014, 405,700 foreign tourists visited the island.[39] Tourists coming from metropolitan France (Europe) were 78% of the total.[39] That same year, the number of tourists from the rest of Europe also increased to an unprecedented 32,400 (a 49% increase). The jump is mainly explained by the increase in German visitors, Swiss and Belgian visitors accounting for 77% of tourists from the rest of Europe. For the first time, the number of German visitors exceeded the threshold of 10,000.[39]

Tourist numbers

Tourism is a major contributor to Réunion's economy.[40] In 2014, 405,700 foreign tourists visited the island.[39] Despite this, the island does not experience mass tourism. The island has impressive natural features inland, but these natural tourist attractions are not well known.[41] In order to boost its tourist industry, the authorities in Réunion heavily promote the country in France and at travel and tourism conferences throughout the world, and diversification of Réunion's tourist industry is a high priority.[40] The tourist industry promotes the island's environment and encourages outdoor activities and ecotourism.[42] Réunion's peak tourist season is from late June to early September, with another busy period from October to early January.[43]

In 2001, 424,000 tourists visited Réunion, creating a revenue of €271.5 million.[44] The number of tourists visiting Réunion decreased in 2004 because of the high cost of flights to the country and competition from the tourist attractions of Mauritius and Seychelles. The 2005 Chikungunya epidemic in Réunion was reported by the French media, which caused a loss of confidence among tourists. Tourist bookings decreased by more than 60% during 2006 and early 2007. One-third of the island's population was infected with the virus by 2007. Large efforts were made to kill the island's mosquito population, and the tourist industry began to recover.[40][42] The island's status as an overseas department of France has benefited its infrastructure.[45]

Tourist attractions

Réunion's tourist attractions are not well known,[42] and include its favourable climate and impressive scenery.[44] The island's topography is very mountainous,[46] with mountains that can be as high as 3,000 m (9,842 ft) close to the coast.[45] The island has many natural tourist attractions, including Piton des Neiges (the highest point on the island),[46] lava cliffs, and deep canyons.[45] Another tourist attraction is the active shield volcano Piton de la Fournaise, one of the most active volcanoes in the world.[47][48] The collapsed calderas of Cirque de Cilaos, Cirque de Mafate, and Cirque de Salazie also draw tourists.[46] The Le Maïdo viewpoint is located at an altitude of 2,205 m (7,232 ft) and has excellent views of the coast.[49] There is good surfing off the island's west coast.[45]

Réunion's capital Saint-Denis and the lagoons of St-Gilles-les Bains also attract tourists.[46] The Domaine du Grand Hazier, an 18th-century home of a sugar planter and official French historical monument, has a large garden with fruit trees and tropical flowers.[46][50] Festivals take place year round throughout the island.[43]

References

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Réunion. |

- Eric Boulogne, « Le petit train longtemps, île de La Réunion », Le siècle des petits trains, éditions Cenomane/La Vie du Rail & des Transports, 1992.

- Le mensuel de l'université (June 2008). Bourbonnais, explorateurs européens et la Fournaise du XVIIe siècle au début du XIXe siècle [Reunion – European explorers and the furnace of the 17th century until the end of the 19th century.]. n°27.

- {lang|fr|Perdu sur la montagne, entre deux parois hautes,/ Il est un lieu sauvage, au rêve hospitalier,/ Qui, dès le premier jour, n'a connu que peu d'hôtes ;}, «Le Bernica », 1862, in Poèmes barbares.

- "Thermalisme à La Réunion ("Thermalism on Réunion")".

- Tourisme et développement (Note d'Information n°34, 01/04/1998)

- « Les DOM-COM : poussières d'empire ou paradis touristiques ? », Jean-Christophe Gay, geography professor at the University of Montpellier III, Alexandra Monot, 31 May 2005, disponible sur cafe.geo.net Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Le Tourisme à La Réunion Archived 2009-05-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Site of the Saint-Pierre Pierrefonds airport Archived 2006-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Journal de l'Île de la Réunion, Monday 26 January 1998, {« {lang|fr|Un enjeu pour la population réunionnaise ? »} ("An issue for the Reunion population?").

- Journal de l'Île de la Réunion, Wednesday 17 June 1998, {lang|fr|« Un outil de référence »}("A reference tool").

- Journal de l'Île de la Réunion, Friday 14 January 2000, {lang|fr|« Tourisme : un toit pour les vacances »}("Tourism: a roof for the holiday")

- Site on the concept of Creole villages

- JIR, Tuesday 22 May 2001, « Saint-Denis : Remise de diplômes Réunion qualité tourisme ».

- JIR, Friday 25 October 2002, « Le club des "chartés" s'agrandit ».

- L'emploi lié à la fréquentation touristique

- JIR, Saturday 23 November 2002, « Le tourisme réunionnais reste stable malgré la conjoncture ».

- « Saint-Louis édite un guide touristique », JIR, Saturday 6 September 2003.

- JIR, 24 November 2003,« Plein phare sur sainte Suzanne ».

- JIR, Wednesday 10 September 2003, {lang|fr|« Une campagne en faveur du tourisme outre-mer »}("A campaign in favour of overseas tourism").

- « Économie de La Réunion », n°116 – second quarter of 2003

- JIR, Saturday 20 September 2003, « Concilier développement du tourisme et environnement ».

- Chiffres de l'Observatoire du Développement de la Réunion , JIR, Monday 5 April 2004, {lang|fr|« Le tourisme génère plus de 6000 emplois salariés »}("Tourism generates over 6000 employee salaries").

- JIR, Saturday 23 April 2005, « Office de tourisme intercommunal » : « [..] le bilan des actions menées par ses trois antennes à Saint-Denis, Sainte-Marie et Sainte-Suzanne tout au long de 2004. Une année couronnée de succès,...du nord : fréquentation touristique en hausse. »

- Schéma de développement touristique de La Réunion, p. 12

- Schéma de développement touristique de La Réunion, p. 61

- JIR, Tuesday 8 March 2005, {lang|fr|« Objectif : un million de touristes en 2020 »}("Objective: a million tourists in 2020").

- JIR, Friday 8 April 2005, {lang|fr|« Un tourisme plus accessible aux handicapés »}("A tourism more accessible for the disabled")

- JIR, 2 August 2005, {lang|fr|« Le tourisme des seniors, un phénomène de masse »}("Senior tourism: a mass phenomenon")

- JIR, Tuesday 30 August 2005, « Assises du tourisme dans les DOM ».

- JIR, Saturday 1 October 2005, {lang|fr|« La Réunion et Maurice s'allient »}("The alliance of Réunion and Mauritius").

- Économie de La Réunion, N° 123 – 1st quarter of 2005

- JIR, Tuesday 28 June 2005, « La Réunion s'exporte pour mieux importer les touristes »

- See the Sunday 3 April 2005 edition of France 2, 30 millions d'amis ("30 million friends")

- Maryann Mott (19 October 2005). "Dogs Used as Shark Bait on French Island". Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- (in French) Chikungunya : Un préjudice limité, sauf pour l'activité touristique - Insee

- JIR, Wednesday 1 February 2006, "Le chik infeste la presse professionnelle du tourisme " (Chik infects the professional tourism press)

- JIR, Wednesday 14 June 2006, « L'île à sensations victime de ses images négatives »

- http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/document.asp?reg_id=24&ref_id=22542

- "Travel and Tourism in Reunion". Euromonitor. April 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

- "Reunion: Overview". Lonely Planet. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- "Reunion: History". Lonely Planet. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- "Reunion: When to Go". Lonely Planet. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- Africa South of the Sahara 2004. Taylor & Francis Group, Routledge. 2003. p. 867. ISBN 1-85743-183-9.

- Boniface, Brain G.; Christopher P. Cooper (2001). Worldwide Destinations: The Geography of Travel and Tourism. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 252. ISBN 0-7506-4231-9.

- "About Reunion". P&O Cruises. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- "Reunion: Country Profile". Travel Africa Magazine. Autumn 1999. Archived from the original on 2008-06-21. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- "Piton de la Fournaise". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- "Reunion: Sights Le Maïdo". Lonely Planet. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-09-17. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- "Reunion: Sights Domaine du Grand Hazier". Lonely Planet. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-09-17. Retrieved 2008-06-23.