Brigitte Bardot

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot (/brɪˌʒiːt bɑːrˈdoʊ/ (![]() listen) brizh-EET bar-DOH; French: [bʁiʒit baʁdo] (

listen) brizh-EET bar-DOH; French: [bʁiʒit baʁdo] (![]() listen); born 28 September 1934), often referred to by her initials B.B.,[1][2] is a French animal rights activist and former actress and singer. Famous for portraying sexually emancipated personae with hedonistic lifestyles, she was one of the best known sex symbols of the 1950s and 1960s. Although she withdrew from the entertainment industry in 1973, she remains a major popular culture icon.[3]

listen); born 28 September 1934), often referred to by her initials B.B.,[1][2] is a French animal rights activist and former actress and singer. Famous for portraying sexually emancipated personae with hedonistic lifestyles, she was one of the best known sex symbols of the 1950s and 1960s. Although she withdrew from the entertainment industry in 1973, she remains a major popular culture icon.[3]

Brigitte Bardot | |

|---|---|

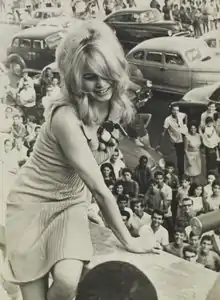

Bardot in 1962 | |

| Born | 28 September 1934 |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) | Bernard d'Ormale

(m. 1992) |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives | Mijanou Bardot (sister) |

| Signature | |

Born and raised in Paris, Bardot was an aspiring ballerina in her early life. She started her acting career in 1952. She achieved international recognition in 1957 for her role in And God Created Woman (1956), and also caught the attention of French intellectuals. She was the subject of Simone de Beauvoir's 1959 essay The Lolita Syndrome, which described her as a "locomotive of women's history" and built upon existentialist themes to declare her the first and most liberated woman of post-war France. Bardot later starred in Jean-Luc Godard's film Le Mépris (1963). For her role in Louis Malle's film Viva Maria! (1965) she was nominated for a BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actress.

Bardot retired from the entertainment industry in 1973. She had acted in 47 films, performed in several musicals and recorded more than 60 songs. She was awarded the Legion of Honour in 1985 but refused to accept it. After retiring, she became an animal rights activist. During the 2000s, she generated controversy by criticizing immigration and Islam in France, and she has been fined five times for inciting racial hatred.[4] She is married to Bernard d'Ormale, a former adviser to Marine Le Pen, France's main far-right political leader.

Early life

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot was born on 28 September 1934 in the 15th arrondissement of Paris, to Louis Bardot (1896–1975) and Anne-Marie Mucel (1912–1978).[5] Bardot's father, originated from Ligny-en-Barrois, was an engineer and the proprietor of several industrial factories in Paris.[6][7] Her mother was the daughter of an insurance company director.[8] She grew up in a conservative Catholic family, as had her father.[9][10] She suffered from amblyopia as a child, which resulted in decreased vision of her left eye.[11] She has one younger sister, Mijanou.[12]

Bardot's childhood was prosperous; she lived in her family's seven-bedroom apartment in the luxurious 16th arrondissement.[10][13] However, she recalled feeling resentful in her early years.[14] Her father demanded she follow strict behavioural standards, including good table manners, and that she wear appropriate clothes.[15] Her mother was extremely selective in choosing companions for her, and as a result Bardot had very few childhood friends.[16] Bardot cited a personal traumatic incident when she and her sister broke her parents' favourite vase while they were playing in the house; her father whipped the sisters 20 times and henceforth treated them like "strangers", demanding them to address their parents by the pronoun "vous", which is a formal style of address, used when speaking to unfamiliar or higher-status persons outside the immediate family.[17] The incident decisively led to Bardot resenting her parents, and to her future rebellious lifestyle.[18]

During World War II, when Paris was occupied by Nazi Germany, Bardot spent more time at home due to increasingly strict civilian surveillance.[13] She became engrossed in dancing to records, which her mother saw as a potential for a ballet career.[13] Bardot was admitted at the age of seven to the private school Cours Hattemer.[19] She went to school three days a week, which gave her ample time to take dance lessons at a local studio, under her mother's arrangements.[16] In 1949, Bardot was accepted at the Conservatoire de Paris. For three years she attended ballet classes held by Russian choreographer Boris Knyazev.[20] She also studied at the Institut de la Tour, a private Catholic high school near her home.[21]

Hélène Gordon-Lazareff, the then-director of the magazines Elle and Le Jardin des Modes, hired Bardot in 1949 as a "junior" fashion model.[22] On 8 March 1950, Bardot (aged 15 at the time) appeared on the cover of Elle, which brought her an acting offer for the film Les Lauriers sont coupés from director Marc Allégret.[23] Her parents opposed her becoming an actress, but her grandfather was supportive, saying that "If this little girl is to become a whore, cinema will not be the cause."[upper-alpha 1] At the audition, Bardot met Roger Vadim, who later notified her that she did not get the role.[25] They subsequently fell in love.[26] Her parents fiercely opposed their relationship; her father announced to her one evening that she would continue her education in England and that he had bought her a train ticket, the journey to take place the following day.[27] Bardot reacted by putting her head into an oven with open fire; her parents stopped her and ultimately accepted the relationship, on condition that she marry Vadim at the age of 18.[28]

Career

Beginning

Bardot appeared on the cover of Elle again in 1952, which landed her a movie offer for the comedy Crazy for Love (1952), starring Bourvil and directed by Jean Boyer.[29] She was paid 200,000 francs (€4,700 in 2019 euros) for the small role portraying a cousin of the main character.[29] Bardot had her second film role in Manina, the Girl in the Bikini (1953),[upper-alpha 2] directed by Willy Rozier.[30] She also had roles in the films The Long Teeth and His Father's Portrait (both 1953).

Bardot had a small role in a Hollywood-financed film being shot in Paris, Act of Love (1953), starring Kirk Douglas. She received media attention when she attended the Cannes Film Festival in April 1953.[31]

Bardot had a leading role in an Italian melodrama, Concert of Intrigue (1954) and in a French adventure film, Caroline and the Rebels (1954). She had a good part as a flirtatious student in School for Love (1955), opposite Jean Marais, for director Marc Allégret.

Bardot played her first sizeable English-language role in Doctor at Sea (1955), as the love interest for Dirk Bogarde. The film was the third-most popular movie at the British box-office that year.[32]

She had a small role in The Grand Maneuver (1955) for director René Clair, supporting Gérard Philipe and Michelle Morgan. The part was bigger in The Light Across the Street (1956) for director Georges Lacombe. She did another with Hollywood film, Helen of Troy, playing Helen's handmaiden.

For the Italian movie Mio figlio Nerone (1956) Bardot was asked by the director to appear as a blonde. Rather than wear a wig to hide her naturally brunette hair she decided to dye her hair. She was so pleased with the results that she decided to retain the hair colour.[33]

Rise to stardom

Bardot then appeared in four movies that made her a star. First up was a musical, Naughty Girl (1956), where Bardot played a troublesome school girl. Directed by Michel Boisrond, it was co-written by Roger Vadim and was a big hit, the 12th most popular film of the year in France.[34] It was followed by a comedy, Plucking the Daisy (1956), written by Vadim with the director Marc Allégret, and another success at France. So too was the comedy The Bride Is Much Too Beautiful (1956) with Louis Jourdan.

Finally there was the melodrama And God Created Woman (1956), Vadim's debut as director, with Bardot starring opposite Jean-Louis Trintignant and Curt Jurgens. The film, about an immoral teenager in a respectable small-town setting, was a huge success, not just in France but also around the world – it was among the ten most popular films in Britain in 1957.[35] It turned Bardot into an international star.[31] From at least 1956,[36] she was being hailed as the "sex kitten".[37][38][39] The film scandalized the United States and theatre managers were arrested for screening it.[40]

During her early career, professional photographer Sam Lévin's photos contributed to the image of Bardot's sensuality. One showed Bardot from behind, dressed in a white corset. British photographer Cornel Lucas made images of Bardot in the 1950s and 1960s that have become representative of her public persona.

Bardot followed And God Created Woman with La Parisienne (1957), a comedy co-starring Charles Boyer for director Boisrond. She was reunited with Vadim in another melodrama The Night Heaven Fell (1958) and played a criminal who seduced Jean Gabin in In Case of Adversity (1958). The latter was the 13th most seen movie of the year in France.[41]

The Female (1959) for director Julien Duvivier was popular, but Babette Goes to War (1959), a comedy set in World War II, was a huge hit, the fourth biggest movie of the year in France.[42] Also widely seen was Come Dance with Me (1959) from Boisrond.

Her next film was the courtroom drama The Truth (1960), from Henri-Georges Clouzot. It was a highly publicised production, which resulted in Bardot having an affair and attempting suicide. The film was Bardot's biggest ever commercial success in France, the third biggest hit of the year, and was nominated for a Best Foreign Film Oscar.[43] Bardot was awarded a David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign actress for her role in the film.

She made a comedy with Vadim, Please, Not Now! (1961) and had a role in the all-star anthology, Famous Love Affairs (1962).

Bardot starred alongside Marcello Mastroianni in a film inspired by her life in A Very Private Affair (Vie privée, 1962), directed by Louis Malle. More popular in France was Love on a Pillow (1962), another for Vadim.

International films and singing career

In the mid-1960s, Bardot made films which seemed to be more aimed at the international market. She starred in Jean-Luc Godard's film Le Mépris (1963), produced by Joseph E. Levine and starring Jack Palance. The following year she co-starred with Anthony Perkins in the comedy Une ravissante idiote (1964).

Dear Brigitte (1965), Bardot's first Hollywood film, was a comedy starring James Stewart as an academic whose son develops a crush on Bardot. Bardot's appearance was relatively brief and the film was not a big hit.

More successful was the Western buddy comedy Viva Maria! (1965) for director Louis Malle, appearing opposite Jeanne Moreau. It was a big hit in France and around the world although it did not break through in the US as much as it had been hoped.[44]

After a cameo in Godard's Masculin Féminin (1966), she had her first outright flop for some years, Two Weeks in September (1968), a French–English co-production. She had a small role in the all-star Spirits of the Dead (1968), acting opposite Alain Delon, then tried a Hollywood film again: Shalako (1968), a Western starring Sean Connery, which was a box-office disappointment.[45]

She participated in several musical shows and recorded many popular songs in the 1960s and 1970s, mostly in collaboration with Serge Gainsbourg, Bob Zagury and Sacha Distel, including "Harley Davidson"; "Je Me Donne À Qui Me Plaît"; "Bubble gum"; "Contact"; "Je Reviendrai Toujours Vers Toi"; "L'Appareil À Sous"; "La Madrague"; "On Déménage"; "Sidonie"; "Tu Veux, Ou Tu Veux Pas?"; "Le Soleil De Ma Vie" (the cover of Stevie Wonder's "You Are the Sunshine of My Life"); and "Je t'aime... moi non-plus". Bardot pleaded with Gainsbourg not to release this duet and he complied with her wishes; the following year, he rerecorded a version with British-born model and actress Jane Birkin that became a massive hit all over Europe. The version with Bardot was issued in 1986 and became a popular download hit in 2006 when Universal Music made its back catalogue available to purchase online, with this version of the song ranking as the third most popular download.[46]

Final films

From 1969 to 1978, Bardot was the official face of Marianne (who had previously been anonymous) to represent the liberty of France.[47]

Les Femmes (1969) was a flop, although the screwball comedy The Bear and the Doll (1970) performed slightly better. Her last few films were mostly comedies: Les Novices (1970), Boulevard du Rhum (1971) (with Lino Ventura). The Legend of Frenchie King (1971) was more popular, helped by Bardot co-starring with Claudia Cardinale. She made one more with Vadim, Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman (1973), playing the title role. Vadim said the film marked "Underneath what people call 'the Bardot myth' was something interesting, even though she was never considered the most professional actress in the world. For years, since she has been growing older, and the Bardot myth has become just a souvenir... I was curious in her as a woman and I had to get to the end of something with her, to get out of her and express many things I felt were in her. Brigitte always gave the impression of sexual freedom – she is a completely open and free person, without any aggression. So I gave her the part of a man – that amused me".[48]

"If Don Juan is not my last movie it will be my next to last", said Bardot during filming.[49] She kept her word and only made one more film, The Edifying and Joyous Story of Colinot (1973).

In 1973, Bardot announced she was retiring from acting as "a way to get out elegantly".[50]

Animal rights activism

After appearing in more than forty motion pictures and recording several music albums she used her fame to promote animal rights.

In 1986, she established the Brigitte Bardot Foundation for the Welfare and Protection of Animals.[51] She became a vegetarian[52] and raised three million francs (€811,000 in 2019 euros) to fund the foundation by auctioning off jewellery and personal belongings.[51]

She is a strong animal rights activist and a major opponent of the consumption of horse meat. In support of animal protection, she condemned seal hunting in Canada during a visit to that country with Paul Watson of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society.[53] On 25 May 2011 the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society renamed its fast interceptor vessel, MV Gojira, as MV Brigitte Bardot in appreciation of her support.[54]

She once had a neighbour's donkey castrated while looking after it, on the grounds of its "sexual harassment" of her own donkey and mare, for which she was taken to court by the donkey's owner in 1989.[55][56] Bardot wrote a 1999 letter to Chinese President Jiang Zemin, published in French magazine VSD, in which she accused the Chinese of "torturing bears and killing the world's last tigers and rhinos to make aphrodisiacs".

She has donated more than $140,000 over two years for a mass sterilization and adoption program for Bucharest's stray dogs, estimated to number 300,000.[57]

In August 2010, Bardot addressed a letter to the Queen of Denmark, Margrethe II of Denmark, appealing for the sovereign to halt the killing of dolphins in the Faroe Islands. In the letter, Bardot describes the activity as a "macabre spectacle" that "is a shame for Denmark and the Faroe Islands ... This is not a hunt but a mass slaughter ... an outmoded tradition that has no acceptable justification in today's world".[58]

On 22 April 2011, French culture minister Frédéric Mitterrand officially included bullfighting in the country's cultural heritage. Bardot wrote him a highly critical letter of protest.[59]

From 2013 onwards, the Brigitte Bardot Foundation in collaboration with Kagyupa International Monlam Trust of India has operated an annual Veterinary Care Camp. She has committed to the cause of animal welfare in Bodhgaya year after year.[60]

On 23 July 2015, Bardot condemned Australian politician Greg Hunt's plan to eradicate 2 million cats to save endangered species such as the Warru and Night parrot.[61]

Personal life

On 20 December 1952, aged 18, Bardot married director Roger Vadim.[62] They divorced in 1957; they had no children together, but remained in touch, and even collaborated on later projects. The stated reason for the divorce was Bardot's affairs with two other men. In 1956, she had become romantically involved with Jean-Louis Trintignant, who was her co-star in And God Created Woman. Trintignant at the time was married to actress Stéphane Audran.[63][31] The two lived together for about two years, spanning the period before and after Bardot's divorce from Vadim, but they never married. Their relationship was complicated by Trintignant's frequent absence due to military service and Bardot's affair with musician Gilbert Bécaud.[63]

In early 1958, her break-up with Trintignant was followed in quick order by a reported nervous breakdown in Italy, according to newspaper reports. A suicide attempt with sleeping pills two days earlier was also noted, but was denied by her public relations manager.[64] She recovered within weeks and began a relationship with actor Jacques Charrier. She became pregnant well before they were married on 18 June 1959. Bardot's only child, her son Nicolas-Jacques Charrier, was born on 11 January 1960. After she and Charrier divorced in 1962, Nicolas was raised in the Charrier family and had little contact with his biological mother until his adulthood.[63]

Bardot had an affair with Glenn Ford in the early 1960s.[65] From 1963 to 1965, she lived with musician Bob Zagury.[66]

Bardot's third marriage was to German millionaire playboy Gunter Sachs, lasting from 14 July 1966 to 7 October 1969, though they had separated the previous year.[63][31][67] In 1968, she began dating Patrick Gilles, who co-starred with her in The Bear and the Doll (1970); but she ended their relationship in spring 1971.[66]

Over the next few years, Bardot dated in succession bartender/ski instructor Christian Kalt, club owner Luigi Rizzi, singer Serge Gainsbourg, writer John Gilmore, actor Warren Beatty, and Laurent Vergez, her co-star in Don Juan, or If Don Juan Were a Woman.[66][68]

In 1974, Bardot appeared in a nude photo shoot in Playboy magazine, which celebrated her 40th birthday. In 1975, she entered a relationship with artist Miroslav Brozek and posed for some of his sculptures. Brozek was also an actor; his stage name is Jean Blaise (acteur).[69] The couple lived together at the house La Madrague in Saint-Tropez. They separated in December 1979.[70]

From 1980 to 1985, Bardot had a live-in relationship with French TV producer Allain Bougrain-Dubourg.[70]

On 28 September 1983, her 49th birthday, Bardot took an overdose of sleeping pills or tranquilizers with red wine. She had to be rushed to the hospital, where her life was saved after a stomach pump was used to evacuate the pills from her body.[70]

Bardot was treated for breast cancer in 1983 and 1984.[71][72]

Bardot's fourth and current husband is Bernard d'Ormale; they have been married since 16 August 1992.[73]

Politics and legal issues

Bardot expressed support for President Charles de Gaulle in the 1960s.[63][74]

In her 1999 book Le Carré de Pluton ("Pluto's Square"), Bardot criticizes the procedure used in the ritual slaughter of sheep during the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha. Additionally, in a section in the book entitled, "Open Letter to My Lost France", Bardot writes that "my country, France, my homeland, my land is again invaded by an overpopulation of foreigners, especially Muslims". For this comment, a French court fined her 30,000 francs (€6,000 in 2019 euros) in June 2000. She had been fined in 1997 for the original publication of this open letter in Le Figaro and again in 1998 for making similar remarks.[75][76][77]

In her 2003 book, Un cri dans le silence (A Scream in the Silence), she contrasted her close gay friends with today's homosexuals, who "jiggle their bottoms, put their little fingers in the air and with their little castrato voices moan about what those ghastly heteros put them through" and said some contemporary homosexuals behave like "fairground freaks".[78] In her own defence, Bardot wrote in a letter to a French gay magazine: "Apart from my husband — who maybe will cross over one day as well — I am entirely surrounded by homos. For years, they have been my support, my friends, my adopted children, my confidants."[79][80]

In her book she wrote about issues such as racial mixing, immigration, the role of women in politics, and Islam. The book also contained a section attacking what she called the mixing of genes and praised previous generations who, she said, had given their lives to push out invaders.[81]

On 10 June 2004, Bardot was convicted for a fourth time by a French court for inciting racial hatred and fined €5,000.[82] Bardot denied the racial hatred charge and apologized in court, saying: "I never knowingly wanted to hurt anybody. It is not in my character."[83]

In 2008, Bardot was convicted of inciting racial/religious hatred in regard to a letter she wrote, a copy of which she sent to Nicolas Sarkozy when he was Interior Minister of France. The letter stated her objections to Muslims in France ritually slaughtering sheep by slitting their throats without anesthetizing them first. She also said, in reference to Muslims, that she was "fed up with being under the thumb of this population which is destroying us, destroying our country and imposing its habits". The trial[84] concluded on 3 June 2008, with a conviction and fine of €15,000, the largest of her fines to date. The prosecutor stated she was tired of charging Bardot with offences related to racial hatred.[80]

During the 2008 United States presidential election, she branded the Republican Party vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin as "stupid" and a "disgrace to women". She criticized the former governor of Alaska for her stance on global warming and gun control. She was also offended by Palin's support for Arctic oil exploration and by her lack of consideration in protecting polar bears.[85]

On 13 August 2010, Bardot lashed out at director Kyle Newman regarding his plan to make a biographical film on her life. She told him, "Wait until I'm dead before you make a movie about my life!" otherwise "sparks will fly".[86] In 2015, she threatened to sue a St. Tropez boutique selling items with her face on them.[87]

In 2018, Bardot expressed support for the yellow vests movement.[88]

On 19 March 2019, Bardot sent an open letter to Réunion prefect Amaury de Saint-Quentin in which she accused to inhabitants of the Indian Ocean island of animal cruelty and referred to them as "aboriginals who have kept the genes of savages."[89] The public prosecutor filed a lawsuit against her the following day, once again for inciting racial hatred.[89]

Connections to Le Pen

Bardot's husband Bernard d'Ormale is a former adviser to Jean-Marie Le Pen, former leader of the far right party National Front (now National Rally). National Rally is the main far-right party in France, known for its nationalist beliefs.[31][74] Bardot expressed support for Marine le Pen, leader of the National Front (National Rally), calling her "the Joan of Arc of the 21st century".[90] She endorsed Le Pen in the 2012 and 2017 French presidential elections.[91][92]

Legacy

In fashion, the Bardot neckline (a wide open neck that exposes both shoulders) is named after her. Bardot popularized this style which is especially used for knitted sweaters or jumpers although it is also used for other tops and dresses. Bardot popularized the bikini in her early films such as Manina (1952) (released in France as Manina, la fille sans voiles). The following year she was also photographed in a bikini on every beach in the south of France during the Cannes Film Festival.[93] She gained additional attention when she filmed ...And God Created Woman (1956) with Jean-Louis Trintignant (released in France as Et Dieu Créa La Femme). In it Bardot portrays an immoral teenager cavorting in a bikini who seduces men in a respectable small-town setting. The film was an international success.[31] The bikini was in the 1950s relatively well accepted in France but was still considered risqué in the United States. As late as 1959, Anne Cole, one of the United States' largest swimsuit designers, said, "It's nothing more than a G-string. It's at the razor's edge of decency."[94]

She also brought into fashion the choucroute ("Sauerkraut") hairstyle (a sort of beehive hair style) and gingham clothes after wearing a checkered pink dress, designed by Jacques Esterel, at her wedding to Charrier.[95] She was the subject of an Andy Warhol painting.

The Bardot pose describes an iconic modeling portrait shot around 1960 where Bardot is dressed only in a pair of black pantyhose, cross-legged over her front and cross-armed over her breasts. This pose has been emulated numerous times by models and celebrities such as Lindsay Lohan, Elle Macpherson and Monica Bellucci.[96]

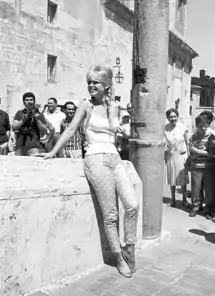

In addition to popularizing the bikini swimming suit, Bardot has been credited with popularizing the city of St. Tropez and the town of Armação dos Búzios in Brazil, which she visited in 1964 with her boyfriend at the time, Brazilian musician Bob Zagury. The place where she stayed in Búzios is today a small hotel, Pousada do Sol, and also a French restaurant, Cigalon.[97] The town hosts a Bardot statue by Christina Motta.[98]

Bardot was idolized by the young John Lennon and Paul McCartney.[99][100] They made plans to shoot a film featuring The Beatles and Bardot, similar to A Hard Day's Night, but the plans were never fulfilled.[31] Lennon's first wife Cynthia Powell lightened her hair color to more closely resemble Bardot, while George Harrison made comparisons between Bardot and his first wife Pattie Boyd, as Cynthia wrote later in A Twist of Lennon. Lennon and Bardot met in person once, in 1968 at the Mayfair Hotel, introduced by Beatles press agent Derek Taylor; a nervous Lennon took LSD before arriving, and neither star impressed the other. (Lennon recalled in a memoir, "I was on acid, and she was on her way out.")[101] According to the liner notes of his first (self-titled) album, musician Bob Dylan dedicated the first song he ever wrote to Bardot. He also mentioned her by name in "I Shall Be Free", which appeared on his second album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. The first-ever official exhibition spotlighting Bardot's influence and legacy opened in Boulogne-Billancourt on 29 September 2009 – a day after her 75th birthday.[102] The Australian pop group Bardot was named after her.

Filmography

Discography

Bardot released several albums and singles during the 1960s and 1970s[103]

- "Sidonie" (1961, Barclay), lyrics by Charles Cros, music by Jean-Max Rivière and Yanis Spanos, guitar by Brigitte – first song, from the film Vie privée

- Brigitte Bardot Sings (1963, Philips) – collaborations by Serge Gainsbourg ("L'Appareil à sous", "Je me donne à qui me plaît"), Jean-Max Rivière as writer ("La Madrague") and singer ("Tiens ! C'est toi!"), Claude Bolling and Gérard Bourgeois

- B.B. (1964, Philips) with Claude Bolling, Alain Goraguer, Gérard Bourgeois

- "Ah ! Les p'tites femmes de Paris", duet with Jeanne Moreau in Viva Maria (1965, Philips), directed by Georges Delerue

- Brigitte Bardot Show 67 (1967, Mercury) with Serge Gainsbourg (writes "Harley Davidson", "Comic Strip", "Contact" and "Bonnie and Clyde"), Sacha Distel, Manitas de Plata, Claude Brasseur and David Bailey

- Brigitte Bardot Show (1968, Mercury), themes by Francis Lai

- Je t'aime... moi non-plus, a 1968 duet with Serge Gainsbourg

- [Burlington Cameo Brings You] Special Bardot (1968. RCA) with "The Good Life" by Sacha Distel and "Comic Strip (with Gainsbourg) in English

- Single Duet with Serge Gainsbourg "Bonnie and Clyde" (Fontana)

- "La Fille de paille"/"Je voudrais perdre la mémoire" (1969, Philips), collaboration with Gérard Lenorman

- Tu veux ou tu veux pas (1970, Barclay) with the hit "Tu veux ou tu veux pas" (the French version of the Brazilian "Nem Vem Que Não Tem"), directed by François Bernheim; "John and Michael", hymn to the collective love; "Mon léopard et moi", a collaboration with Darry Cowl, and "Depuis que tu m'as quitté"

- "Nue au soleil"/"C'est une bossa nova" (1970, Barclay)

- "Chacun son homme", duet with Annie Girardot in Les Novices (1970, Barclay)

- "Boulevard du rhum" and "Plaisir d'amour", duet with Guy Marchand, in Boulevard du rhum (1971, Barclay)

- "Vous ma lady", duet with Laurent Vergez, and "Tu es venu mon amour" (1973, Barclay)

- "Le Soleil de ma vie", duet with Sacha Distel

- "Toutes les bêtes sont à aimer" (1982, Polydor)

Books

Bardot has also written five books:

- Noonoah: Le petit phoque blanc (Grasset, 1978)

- Initales B.B. (autobiography, Grasset & Fasquelle, 1996)

- Le Carré de Pluton (Grasset & Fasquelle, 1999)

- Un Cri Dans Le Silence (Editions Du Rocher, 2003)

- Pourquoi? (Editions Du Rocher, 2006)

See also

References

Notes

Footnotes

- "And Bardot Became BB". Institut français du Royaume-Uni. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Probst 2012, p. 7.

- Cherry 2016, p. 134; Vincendeau 1992, p. 73–76.

- "Brigitte Bardot at 80: still outrageous, outspoken and controversial". The Guardian. 20 September 2014.

- Bardot 1996, p. 15.

- "Brigitte Bardot: 'J'en ai les larmes aux yeux'". Le Républicain Lorrain (in French). 23 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013.

- Singer 2006, p. 6.

- Bigot 2014, p. 12.

- Bigot 2014, p. 11.

- Poirier, Agnès (20 September 2014). "Brigitte Bardot at 80: still outrageous, outspoken and controversial". The Observer. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Lelièvre 2012, p. 18.

- Bardot 1996, p. 45.

- Singer 2006, p. 10.

- Bardot 1996, p. 45; Singer 2006, p. 10–14.

- Singer 2006, p. 10–12.

- Singer 2006, p. 10–11.

- Singer 2006, p. 11–12.

- Singer 2006, p. 12.

- Singer 2006, p. 11.

- Caron 2009, p. 62.

- Pigozzi, Caroline. "Bardot s'en va toujours en guerre... pour les animaux". Paris Match (January 2018). pp. 76–83.

- Bardot 1996, p. 67.

- Singer 2006, p. 19.

- Bardot 1996, p. 68–69.

- Bardot 1996, p. 69.

- Bardot 1996, p. 70.

- Bardot 1996, p. 72.

- Bardot 1996, p. 73; Singer 2006, p. 22.

- Bardot 1996, p. 81.

- Bardot 1996, p. 84.

- Robinson, Jeffrey (1994). Bardot — Two Lives (First British ed.). London: Simon & Schuster. ASIN: B000KK1LBM.

- "'The Dam Busters'." Times [London, England] 29 December 1955: 12. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 11 July 2012.

- Servat. Page 76.

- Box office figures in France for 1956 at Box Office Story

- Most Popular Film of the Year. The Times (London, England), Thursday, 12 December 1957; pg. 3; Issue 54022.

- "Mam'selle Kitten New box-office beauty". Australian Women's Weekly. 5 December 1956. p. 32. Retrieved 5 March 2019 – via Trove.

- "Brigitte Bardot: her life and times so far – in pictures". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Brigitte Bardot: Rare and Classic Photos of the Original 'Sex Kitten'". time.com. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- The earliest use cited in the OED Online (accessed 26 November 2011) is in the Daily Sketch, 2 June 1958.

- Poirier, Agnès (22 September 2009). "Happy birthday, Brigitte Bardot". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- "Box office information for Love is My Profession". Box office story.

- "1959 French box office". Box Office Story. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Box office information for film at Box Office Story

- Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1987 p. 281.

- "ABC's 5 Years of Film Production Profits & Losses", Variety, 31 May 1973 p. 3.

- "Bardot revived as download star". BBC News. 17 October 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- Anne-Marie Sohn (teacher at the ÉNS-Lyon), Marianne ou l'histoire de l'idée républicaine aux XIXe et XXe siècles à la lumière de ses représentations (résumé of Maurice Agulhon's three books, Marianne au combat, Marianne au pouvoir and Les métamorphoses de Marianne) (in French)

- Wilson, Timothy (7 April 1973). "ROGER VADIM". The Guardian. London (UK). p. 9.

- Morgan, Gwen (4 March 1973). "Brigitte Bardot: No longer a sex symbol". Chicago Tribune. p. d3.

- "Brigitte Bardot Gives Up Films at Age of 39". The Modesto Bee. Modesto, California. UPI. 7 June 1973. p. A-8. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- "Brigitte Bardot foundation for the welfare and protection of animals". fondationbrigittebardot.fr. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- Follain, John (9 April 2006) Brigitte Bardot profile, The Times Online: Life & Style; retrieved 2 April 2009.

- "Hardline warrior in war to save the whale". The New Zealand Herald. 11 January 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Sea Shepherd Conservation Society". Seashepherd.org. 25 May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- "PHOTOICON ONLINE FEATURES: Andy Martin: Brigitte Bardot". Photoicon.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "Mr Pop History". Mr Pop History. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "Bardot 'saves' Bucharest's dogs". BBC News. 2 March 2001. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Brigitte Bardot pleads to Denmark in dolphin 'slaughter', AFP, 19 August 2010.

- Victoria Ward, Devorah Lauter (4 January 2013). "Brigitte Bardot's sick elephants add to circus over French wealth tax protests", telegraph.co.uk; accessed 4 August 2015.

- Bardot commits to animal welfare in Bodhgaya Archived 19 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, phayul.com; accessed 4 August 2015.

- "Bardot condemns Australia's plan to cull 2 million feral cats". ABC News. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- Neuhoff, Éric (12 August 2013). "Brigitte Bardot et Roger Vadim – Le loup et la biche". Le Figaro (in French). p. 18.

- Bardot, Brigitte (1996). Initiales B.B. Grasset & Fasquelle. ISBN 978-2-246-52601-8.

- "Brigitte Bardot in Italy After Breakdown". The Los Angeles Times. 9 February 1958. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- "A Ford Fiesta".

- Singer, B. (2006). Brigitte Bardot: A Biography. McFarland, Incorporated Publishers. ISBN 9780786484263. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Gunter Sachs". The Daily Telegraph. London. 9 May 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Malossi, G. (1996). Latin Lover: The Passionate South. Charta. ISBN 9788881580491. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Brigitte Bardot and sculptor Miroslav Brozek at La Madrague in St.-Tropez. June 1975, Getty Images

- Carlson, Peter (24 October 1983). "Swept Away by Her Sadness". People. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Famous breast cancer survivors, ecoglamazine.blogspot.com; accessed 4 August 2015.

- Famous proof that breast cancer is survivable, beliefnet.com; accessed 4 August 2015.

- Goodman, Mark (30 November 1992). "A Bardot Mystery". People. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Riding, Alan (30 March 1994). "Drinking champagne with: Brigitte Bardot; And God Created An Animal Lover". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- "Bardot fined for racist remarks". London: BBC News. 16 June 2000. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "Bardot racism conviction upheld". London: BBC News. 11 May 2001. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- "Bardot anti-Muslim comments draw fire". London: BBC News. 14 May 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- Webster, Paul; Hearst, David (5 May 2003). "Anti-gay, anti-Islam Bardot to be sued". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- "Brigitte a Political Animal by David Usborne". The Independent. 24 March 2006. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- "Bardot fine for stoking race hate". London, UK: BBC News. 3 June 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- "Bardot fined for 'race hate' book". BBC News. 10 June 2004. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- Larent, Shermy (12 May 2003). "Brigitte Bardot unleashes colourful diatribe against Muslims and modern France". Indybay. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "Bardot denies 'race hate' charge". BBC News. 7 May 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- "Brigitte Bardot: Heroine of Free Speech". Brusselsjournal.com. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "Brigitte Bardot calls Sarah Palin a 'disgrace to women'" The Telegraph, 8 October 2008.

- "Brigitte Bardot: 'Wait Until I'M Dead Before You Make Biopic'". Showbiz Spy. 14 August 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- Samuel, Henry (9 June 2015). "Brigitte Bardot declares war on commercial 'abuse' of her image". The Daily Telegraph.

- Fourny, Marc (3 December 2018). "Brigitte Bardot demande " une prime de Noël " pour les Gilets jaunes". Le Point (in French). Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- "Brigitte Bardot accused of racism in lawsuit for calling aboriginals a 'degenerate population'". New York Daily News. 20 March 2019.

- Chazan, David (22 August 2014). "Brigitte Bardot calls Marine Le Pen 'modern Joan of Arc". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- Willsher, Kim (13 September 2012). "Brigitte Bardot: celebrity crushed me". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Zoltany, Monika (7 May 2017). "Brigitte Bardot Supports Underdog Marine Le Pen in French Presidential Election, Says Macron Has Cold Eyes". Inquisitr. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "Bikinis: a brief history". Telegraph. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- Johnson, William Oscar (7 February 1989). "In The Swim". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Style Icon: Brigitte Bardot". Femminastyle.com. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- "The Bardot Pose: just a pair of black stockings | The Heritage Studio". theheritagestudio.com. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "TOemBUZIOS.com". toembuzios.com (in Portuguese). TOemBUZIOS.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- "BúziosOnline.com". BúziosOnline.com. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Miles, Barry (1998). Many Years From Now. Vintage–Random House. ISBN 978-0-7493-8658-0. pg. 69.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. Little, Brown and Company (New York). ISBN 978-1-84513-160-9. pg. 171.

- Lennon, John (1986). Skywriting by Word of Mouth. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-015656-5. pg. 24.

- Brigitte Bardot at 75: the exhibition Archived 26 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, connexionfrance.com, September 2009; accessed 4 August 2015.

- "Brigitte Bardot discography". allmusic. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

Sources

- Bardot, Brigitte (1996). Initiales B.B. : Mémoires (in French). Éditions Grasset]. ISBN 978-2-246526018.

- Bigot, Yves (2014). Brigitte Bardot. La femme la plus belle et la plus scandaleuse au monde (in French). Don Quichotte. ISBN 978-2-359490145.

- Caron, Leslie (2009). Thank Heaven. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670021345.

- Cherry, Elizabeth (2016). Culture and Activism: Animal Rights in France and the United States. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317156154.

- Lelièvre, Marie-Dominique (2012). Brigitte Bardot – Plein la vue (in French). Groupe Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-124624-9.

- Probst, Ernst (2012). Das Sexsymbol der 1950-er Jahre (in German). GRIN Publishing. ISBN 978-3-656186212.

- Singer, Barnett (2006). Brigitte Bardot : A Biography. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0786425150.

- Vincendeau, Ginette (March 1992). "The old and the new: Brigitte Bardot in 1950s France". Paragraph. Edinburgh University Press. 15 (1): 73–96. doi:10.3366/para.1992.0004. JSTOR 43151735.

Literature

External links

- Fondation Brigitte Bardot (in French)

- Brigitte Bardot at IMDb

- Brigitte Bardot at the TCM Movie Database

- Brigitte Bardot at AllMovie