Tropical Storm Bonnie (2004)

Tropical Storm Bonnie was a tropical storm that made landfall on Florida in August 2004. The second storm of the 2004 Atlantic hurricane season, Bonnie developed from a tropical wave on August 3 to the east of the Lesser Antilles. After moving through the islands, its fast forward motion caused it to dissipate. However, it later regenerated into a tropical storm near Yucatán Peninsula. Bonnie attained peak winds of 65 miles per hour (105 km/h) over the Gulf of Mexico, turned to the northeast, and hit Florida as a 45 miles per hour (72 km/h) tropical storm. The storm accelerated to the northeast and became an extratropical cyclone to the east of New Jersey. Bonnie was the first of five tropical systems to make landfall on Florida in the 2004 Atlantic hurricane season, and the second of a record eight disturbances to reach tropical storm strength during the month of August.

| Tropical storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Tropical Storm Bonnie near peak intensity on August 11 | |

| Formed | August 3, 2004 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 14, 2004 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 65 mph (100 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 1001 mbar (hPa); 29.56 inHg |

| Fatalities | 3 direct, 1 indirect |

| Damage | $1.27 million (2004 USD) |

| Areas affected | Lesser Antilles, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Cuba, Yucatán Peninsula, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maine |

| Part of the 2004 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Bonnie's impact was minimal. Throughout the Caribbean Sea, the storm's effects consisted primarily of light rainfall, and in Florida, the precipitation caused flooding and minor damage. The tropical storm caused a tornado outbreak across the Southeastern United States which killed three people and inflicted over $1 million (2004 USD) in damage. Bonnie made landfall in Florida the day before Hurricane Charley struck.

Meteorological history

The origins of Bonnie were in a tropical wave that emerged from the coast of Africa on July 29 and entered the Atlantic Ocean. It moved westward, attaining convection and a mid-level circulation. Convection steadily increased, and, upon the development of a low-level circulation center, the system organized into Tropical Depression Two on August 3 while 415 miles (670 km) east of Barbados. It moved rapidly westward at speeds of up to 23 mph (37 km/h); after crossing through the Lesser Antilles on August 4, it degenerated back into a tropical wave.[1] The tropical wave continued to move rapidly to the west-northwest, until it reached the western Caribbean Sea. While south of Cuba and through the Cayman Islands, the system slowed down to regenerate convection, and it re-developed into a tropical depression on August 8.[1] Operationally, the system was classified a tropical wave until a day later.[2] The depression moved through the Yucatán Channel, and intensified into Tropical Storm Bonnie on August 9 while 70 miles (115 km) north of the Yucatán Peninsula.[1]

.jpg.webp)

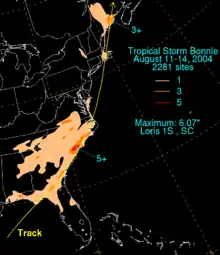

Bonnie continued to the west-northwest; late on August 9, the storm presented a 9-mile (15-km) wide eyewall, a very unusual occurrence in a small and weak tropical storm.[3] Bonnie quickly strengthened while turning to the north, a directional shift caused by a break in the mid-level ridge.[4] The storm briefly weakened late on August 10; it re-strengthened again the following day to attain a peak intensity of 65 mph (100 km/h). Soon after, strong southwesterly wind shear disrupted the storm, causing Bonnie to weaken again. On August 12, Bonnie made landfall just south of Apalachicola as a 45 mph (75 km/h) tropical storm. It quickly weakened to a tropical depression, and accelerated northeastward through the southeastern United States. After paralleling the Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina coastlines, Bonnie lost its tropical characteristics on August 14 to the east of New Jersey.[1] Its remnant low continued northeastward, making landfall in Massachusetts and Maine and continuing into Atlantic Canada.[5]

Preparations

About 16 hours before the storm moved through the Lesser Antilles, the government of Saint Lucia declared a tropical storm warning. Guadeloupe, Martinique, Dominica, St. Maarten, Saba, St. Eustatius, Puerto Rico and the U.S Virgin Islands issued tropical storm watches.[1] Combined with the threat of Hurricane Charley, Bonnie forced the evacuation of 154 oil platforms and 32 oil rigs. The cease in production was equivalent to over 1.2 million barrels of loss in crude oil, or 0.2% of the annual oil production in the Gulf of Mexico. Natural gas reserves were also limited. The lack of gas production due to the storms was equivalent to 7.4% of the total daily production in the Gulf of Mexico.[6]

Early forecasts suggested that Bonnie would attain 80 mph (130 km/h) winds or Category 1 status.[4] In response to the threat, 15 shelters in 7 northwestern Florida counties were put on standby.[7] In the hours prior to landfall,2 shelters were opened, 4 were put on standby, and health and cleanup teams were deployed to the area.[8] Parts of Gadsden, Wakulla, and Levy Counties issued voluntary evacuations, and numerous schools were closed. In anticipation of the storm, Florida Governor Jeb Bush issued a state of emergency.[9]

Impact

Bonnie was a weak storm through most of its path, dropping only light rainfall and causing minimal damage. South Carolina and North Carolina experienced the worst of the storm, where a tornado outbreak killed three people and caused moderate damage.

Caribbean Sea

As a tropical depression, the storm moved rapidly through the Lesser Antilles; consequently, most islands only experienced minor effects. For example, Saint Lucia received light and sporadic rain showers, accompanied by sustained winds of 20–25 mph (32–40 km/h) and gusts to 35 mph (55 km/h).[10] In Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, however, the depression dropped up to 9.2 inches (235 mm) of rain in 24 hours. The rainfall blocked storm drains, including those near the airport, which was forced to shut down. The rainfall caused debris to collect on roads throughout the island.[11] Although the storm passed just 70 miles (110 km) north of the Yucatán Peninsula, the storm dropped only 0.6 inches (15 mm) of rain due to its small size.[12]

North America

In Florida, Bonnie produced up to 4.1 inches (104 mm) of rainfall in Pace, with peak wind gusts of 42 mph (68 km/h). Bonnie was accompanied by a 4 ft (1.2 m) storm surge; moderate wave action caused slight beach erosion. Rainfall and storm surge flooded roads, forcing the evacuation of 2,000 residents in Taylor County. The winds downed trees and caused scattered power outages.[13] A tornado in Jacksonville damaged several businesses and houses.[14][15]

Bonnie triggered a tornado outbreak throughout portions of the Mid-Atlantic states. One tornado in Pender County, North Carolina destroyed 17 homes and damaged 59 houses, causing three deaths and $1.27 million in damage (2004 USD).[16] In Stella, Bonnie generated a waterspout that struck a campground, damaged nine trailers, and wrecked small boats.[17] A tornado in Richlands damaged several houses as well.[18] A suspected tornado in Danville, Virginia destroyed the roofs of several businesses.[14] In South Carolina, tornadoes across the state damaged nine homes. Also, rainfall peaking at 6.07 inches (154 mm) in Loris[5] caused flooding across the state. The flooding, including a one-foot depth along U.S. Route 501, washed away a road and a bridge in Greenville County. In addition, 600 people across the state were left without electricity.[19]

In Pennsylvania, the remnants of the storm dropped up to 8 inches (200 mm) of rain in Tannersville. The rainfall caused the Schuylkill River to reach a crest peak of 12.89 ft (4 m) at Berne. The flooding blocked several roads across eastern Pennsylvania. In addition, Bonnie produced gusty winds, leaving thousands without power.[20] In Delaware, the storm dropped up to 4 inches (100 mm) of rain, forcing 100 to evacuate from the floodwaters. The flooding closed part of U.S. Route 13, and an overflown creek in New Castle County caused moderate flooding damage to stores.[13] In Maine, moisture from the remnants of Bonnie produced heavy rainfall, with localized totals of up to 10 inches (250 mm). The rainfall flooded or washed out roads across the eastern portion of the state. In Aroostook County, near the town of St. Francis, the rainfall caused a mudslide which narrowed a county road to one lane.[21]

As an extratropical low combined with a frontal system, Bonnie continued to produce moderate rainfall in Canada, peaking at 3.5 inches (90 mm) in Edmundston, New Brunswick. The rainfall caused basement flooding and road washouts; slick roads caused a traffic fatality in Edmundston.[22]

Aftermath and records

Twenty-two hours after Bonnie struck Florida, Hurricane Charley passed over the Dry Tortugas. This was the first time in recorded history that two tropical storms struck Florida within 1 day. Previously, Hurricane Gordon and Tropical Storm Helene struck the state within five days of each other in September 2000. Originally, it was thought that two storms in the 1906 season hit the state within 12 hours;[23] however, the suspected tropical storm was determined to be a tropical depression in a more recent analysis.[24] Bonnie was the first of five tropical systems to make landfall in Florida during the 2004 Atlantic hurricane season, and the second of a record eight disturbances to reach tropical storm strength during the month of August.[25]

Because Bonnie hit Florida immediately before Charley, damage between the two storms was often difficult to differentiate. President George W. Bush responded to the storm by declaring much of Florida a Federal Disaster Area on August 13, 2004.[26]

See also

References

- National Hurricane Center (2004). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- National Hurricane Center (2004). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Tropical Discussion #7". Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- National Hurricane Center (2004). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Tropical Discussion #8". Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- National Hurricane Center (2004). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Tropical Discussion #10". Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (2006). "Rainfall Summary for Tropical Storm Bonnie". Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- United States Department of the Interior (2004). "Tropical Storm Bonnie and Hurricane Charley Evacuation and Production Shut-in Statistics". Archived from the original on July 18, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- Capital City Area Red Cross (2004). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Situation Report #1" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- Capital City Area Red Cross (2004). "Tropical Storm Bonnie Situation Report #1" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- Florida State Emergency Response Team (2004). "Situation Report #1" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- Mike Davis (2004). "Unofficial Reports from St. Lucia". Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- National Emergency Office, St Vincent (2004). "Airport in St Vincent temporarily closed due to flooding". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- Dir. Gral. Adj. de Oceanografia, Hidrografia y Meteorología (2004). "Tormenta Tropical Bonnie" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- "Storm data and unusual weather phenomena, August 2004 (Alabama-Florida)". World Meteorological Organization. 2004. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- Insurance Journal (2004). "Storm Bonnie Spawns Tornadoes from Fla. to Va". Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- "Bonnie-Spawned Tornado Rips Through Northwest Jacksonville". News4Jax.com. August 12, 2004. Archived from the original on August 15, 2004. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- Wilmington National Weather Service (2004). "Final Pender County Tornado Damage Assessment". Archived from the original on March 12, 2005. Retrieved May 22, 2006.

- Timmi Toler (2004). "Waterspout damages Stella campground". Jacksonville Daily News. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2004.

- Roselee Papandrea (2004). "Bonnie makes presence felt". Jacksonville Daily News. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- Associated Press (2004). "Bonnie brings high winds, tornadoes around SC". Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- "Storm data and unusual weather phenomena, August 2004 (New York-Pennsylvania)". World Meteorological Organization. 2004. Archived from the original on April 17, 2006. Retrieved May 19, 2006.

- "Storm data and unusual weather phenomena, August 2004 (Kansas-Michigan)". World Meteorological Organization. 2004. Archived from the original on April 26, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- Canadian Hurricane Centre (2004). "2004 Tropical Cyclone Season Summary". Archived from the original on May 1, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- David Royse (2004). "How Rare is Tropical Storm Double Trouble?". Associated Press. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- HURDAT (2004). "HURDAT Re-Analysis (1901–1910)". Retrieved May 18, 2006.

- National Hurricane Center (2004). "August 2004 Monthly Tropical Weather Summary". Retrieved May 18, 2004.

- FEMA (2004). "Florida Hurricane Charley and Tropical Storm Bonnie". Archived from the original on February 22, 2006. Retrieved May 18, 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tropical Storm Bonnie (2004). |