Typhon

Typhon (/ˈtaɪfɒn, -fən/; Greek: Τυφῶν, [typʰɔ̂ːn]), also Typhoeus (/taɪˈfiːəs/; Τυφωεύς), Typhaon (Τυφάων) or Typhos (Τυφώς), was a monstrous serpentine giant and one of the deadliest creatures in Greek mythology. According to Hesiod, Typhon was the son of Gaia and Tartarus. However, one source has Typhon as the son of Hera alone, while another makes Typhon the offspring of Cronus. Typhon and his mate Echidna were the progenitors of many famous monsters.

Typhon attempted to overthrow Zeus for the supremacy of the cosmos. The two fought a cataclysmic battle, which Zeus finally won with the aid of his thunderbolts. Defeated, Typhon was cast into Tartarus, or buried underneath Mount Etna, or the island of Ischia.

Typhon mythology is part of the Greek succession myth, which explained how Zeus came to rule the gods. Typhon's story is also connected with that of Python (the serpent killed by Apollo), and both stories probably derived from several Near Eastern antecedents. Typhon was (from c. 500 BC) also identified with the Egyptian god of destruction Set. In later accounts Typhon was often confused with the Giants.

Mythology

Birth

According to Hesiod's Theogony (c. 8th – 7th century BC), Typhon was the son of Gaia (Earth) and Tartarus: "when Zeus had driven the Titans from heaven, huge Earth bore her youngest child Typhoeus of the love of Tartarus, by the aid of golden Aphrodite".[2] The mythographer Apollodorus (1st or 2nd century AD) adds that Gaia bore Typhon in anger at the gods for their destruction of her offspring the Giants.[3]

Numerous other sources mention Typhon as being the offspring of Gaia, or simply "earth-born", with no mention of Tartarus.[4] However, according to the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (6th century BC), Typhon was the child of Hera alone.[5] Hera, angry at Zeus for having given birth to Athena by himself, prayed to Gaia, Uranus, and the Titans, to give her a son stronger than Zeus, then slapped the ground and became pregnant. Hera gave the infant Typhon to the serpent Python to raise, and Typhon grew up to become a great bane to mortals.[6]

Several sources locate Typhon's birth and dwelling place in Cilicia, and in particular the region in the vicinity of the ancient Cilician coastal city of Corycus (modern Kızkalesi, Turkey). The poet Pindar (c. 470 BC) calls Typhon "Cilician,"[7] and says that Typhon was born in Cilicia and nurtured in "the famous Cilician cave",[8] an apparent allusion to the Corycian cave in Turkey.[9] In Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound, Typhon is called the "dweller of the Cilician caves",[10] and both Apollodorus and the poet Nonnus (4th or 5th century AD) have Typhon born in Cilicia.[11]

The b scholia to Iliad 2.783, preserving a possibly Orphic tradition, has Typhon born in Cilicia, as the offspring of Cronus. Gaia, angry at the destruction of the Giants, slanders Zeus to Hera. So Hera goes to Zeus' father Cronus (whom Zeus had overthrown) and Cronus gives Hera two eggs smeared with his own semen, telling her to bury them, and that from them would be born one who would overthrow Zeus. Hera, angry at Zeus, buries the eggs in Cilicia "under Arimon", but when Typhon is born, Hera, now reconciled with Zeus, informs him.[12]

Descriptions

According to Hesiod, Typhon was "terrible, outrageous and lawless",[13] immensely powerful, and on his shoulders were one hundred snake heads, that emitted fire and every kind of noise:

Strength was with his hands in all that he did and the feet of the strong god were untiring. From his shoulders grew a hundred heads of a snake, a fearful dragon, with dark, flickering tongues, and from under the brows of his eyes in his marvellous heads flashed fire, and fire burned from his heads as he glared. And there were voices in all his dreadful heads which uttered every kind of sound unspeakable; for at one time they made sounds such that the gods understood, but at another, the noise of a bull bellowing aloud in proud ungovernable fury; and at another, the sound of a lion, relentless of heart; and at another, sounds like whelps, wonderful to hear; and again, at another, he would hiss, so that the high mountains re-echoed.[14]

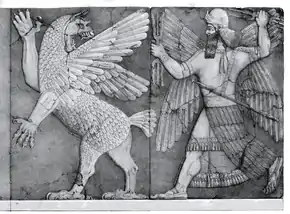

The Homeric Hymn to Apollo describes Typhon as "fell" and "cruel", and like neither gods nor men.[15] Three of Pindar's poems have Typhon as hundred-headed (as in Hesiod),[16] while apparently a fourth gives him only fifty heads,[17] but a hundred heads for Typhon became standard.[18] A Chalcidian hydria (c. 540–530 BC), depicts Typhon as a winged humanoid from the waist up, with two snake tails below.[19] Aeschylus calls Typhon "fire-breathing".[20] For Nicander (2nd century BC), Typhon was a monster of enormous strength, and strange appearance, with many heads, hands, and wings, and with huge snake coils coming from his thighs.[21]

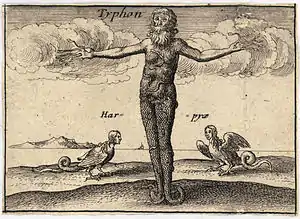

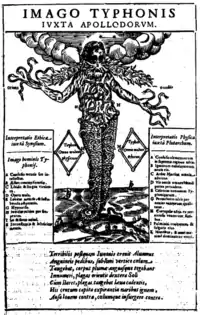

Apollodorus describes Typhon as a huge winged monster, whose head "brushed the stars", human in form above the waist, with snake coils below, and fire flashing from his eyes:

In size and strength he surpassed all the offspring of Earth. As far as the thighs he was of human shape and of such prodigious bulk that he out-topped all the mountains, and his head often brushed the stars. One of his hands reached out to the west and the other to the east, and from them projected a hundred dragons' heads. From the thighs downward he had huge coils of vipers, which when drawn out, reached to his very head and emitted a loud hissing. His body was all winged: unkempt hair streamed on the wind from his head and cheeks; and fire flashed from his eyes.

The most elaborate description of Typhon is found in Nonnus's Dionysiaca. Nonnus makes numerous references to Typhon's serpentine nature,[22] giving him a "tangled army of snakes",[23] snaky feet,[24] and hair.[25] According to Nonnus, Typhon was a "poison-spitting viper",[26] whose "every hair belched viper-poison",[27] and Typhon "spat out showers of poison from his throat; the mountain torrents were swollen, as the monster showered fountains from the viperish bristles of his high head",[28] and "the water-snakes of the monster's viperish feet crawl into the caverns underground, spitting poison!".[29]

Following Hesiod and others, Nonnus gives Typhon many heads (though untotaled), but in addition to snake heads,[30] Nonnus also gives Typhon many other animal heads, including leopards, lions, bulls, boars, bears, cattle, wolves, and dogs, which combine to make 'the cries of all wild beasts together',[31] and a "babel of screaming sounds".[32] Nonnus also gives Typhon "legions of arms innumerable",[33] and where Nicander had only said that Typhon had "many" hands, and Ovid had given Typhon a hundred hands, Nonnus gives Typhon two hundred.[34]

Offspring

According to Hesiod's Theogony, Typhon "was joined in love" to Echidna, a monstrous half-woman and half-snake, who bore Typhon "fierce offspring".[35] First, according to Hesiod, there was Orthrus,[36] the two-headed dog who guarded the Cattle of Geryon, second Cerberus,[37] the multiheaded dog who guarded the gates of Hades, and third the Lernaean Hydra,[38] the many-headed serpent who, when one of its heads was cut off, grew two more. The Theogony next mentions an ambiguous "she", which might refer to Echidna, as the mother of the Chimera (a fire-breathing beast that was part lion, part goat, and had a snake-headed tail) with Typhon then being the father.[39]

While mentioning Cerberus and "other monsters" as being the offspring of Echidna and Typhon, the mythographer Acusilaus (6th century BC) adds the Caucasian Eagle that ate the liver of Prometheus.[40] The mythographer Pherecydes of Athens (5th century BC) also names Prometheus' eagle,[41] and adds Ladon (though Pherecydes does not use this name), the dragon that guarded the golden apples in the Garden of the Hesperides (according to Hesiod, the offspring of Ceto and Phorcys).[42] The lyric poet Lasus of Hermione (6th century BC) adds the Sphinx.[43]

Later authors mostly retain these offspring of Typhon by Echidna, while adding others. Apollodorus, in addition to naming as their offspring Orthrus, the Chimera (citing Hesiod as his source) the Caucasian Eagle, Ladon, and the Sphinx, also adds the Nemean lion (no mother is given), and the Crommyonian Sow, killed by the hero Theseus (unmentioned by Hesiod).[44]

Hyginus (1st century BC),[45] in his list of offspring of Typhon (all by Echidna), retains from the above: Cerberus, the Chimera, the Sphinx, the Hydra and Ladon, and adds "Gorgon" (by which Hyginus means the mother of Medusa, whereas Hesiod's three Gorgons, of which Medusa was one, were the daughters of Ceto and Phorcys), the Colchian dragon that guarded the Golden Fleece[46] and Scylla.[47] The Harpies, in Hesiod the daughters of Thaumas and the Oceanid Electra,[48] in one source, are said to be the daughters of Typhon.[49]

The sea serpents which attacked the Trojan priest Laocoön, during the Trojan War, were perhaps supposed to be the progeny of Typhon and Echidna.[50] According to Hesiod, the defeated Typhon is the father of destructive storm winds.[51]

Battle with Zeus

Typhon challenged Zeus for rule of the cosmos.[52] The earliest mention of Typhon, and his only occurrence in Homer, is a passing reference in the Iliad to Zeus striking the ground around where Typhon lies defeated.[53] Hesiod's Theogony gives the first account of their battle. According to Hesiod, without the quick action of Zeus, Typhon would have "come to reign over mortals and immortals".[54] In the Theogony Zeus and Typhon meet in cataclysmic conflict:

[Zeus] thundered hard and mightily: and the earth around resounded terribly and the wide heaven above, and the sea and Ocean's streams and the nether parts of the earth. Great Olympus reeled beneath the divine feet of the king as he arose and earth groaned thereat. And through the two of them heat took hold on the dark-blue sea, through the thunder and lightning, and through the fire from the monster, and the scorching winds and blazing thunderbolt. The whole earth seethed, and sky and sea: and the long waves raged along the beaches round and about at the rush of the deathless gods: and there arose an endless shaking. Hades trembled where he rules over the dead below, and the Titans under Tartarus who live with Cronos, because of the unending clamor and the fearful strife.[55]

Zeus with his thunderbolt easily overcomes Typhon,[56] who is thrown down to earth in a fiery crash:

So when Zeus had raised up his might and seized his arms, thunder and lightning and lurid thunderbolt, he leaped from Olympus and struck him, and burned all the marvellous heads of the monster about him. But when Zeus had conquered him and lashed him with strokes, Typhoeus was hurled down, a maimed wreck, so that the huge earth groaned. And flame shot forth from the thunderstricken lord in the dim rugged glens of the mount, when he was smitten. A great part of huge earth was scorched by the terrible vapor and melted as tin melts when heated by men's art in channelled crucibles; or as iron, which is hardest of all things, is shortened by glowing fire in mountain glens and melts in the divine earth through the strength of Hephaestus. Even so, then, the earth melted in the glow of the blazing fire.[57]

Defeated, Typhon is cast into Tartarus by an angry Zeus.[58]

Epimenides (7th or 6th century BC) seemingly knew a different version of the story, in which Typhon enters Zeus' palace while Zeus is asleep, but Zeus awakes and kills Typhon with a thunderbolt.[59] Pindar apparently knew of a tradition which had the gods, in order to escape from Typhon, transform themselves into animals, and flee to Egypt.[60] Pindar calls Typhon the "enemy of the gods",[61] and says that he was defeated by Zeus' thunderbolt.[62] In one poem Pindar has Typhon being held prisoner by Zeus under Etna,[63] and in another says that Typhon "lies in dread Tartarus", stretched out underground between Mount Etna and Cumae.[64] In Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound, a "hissing" Typhon, his eyes flashing, "withstood all the gods", but "the unsleeping bolt of Zeus" struck him, and "he was burnt to ashes and his strength blasted from him by the lightning bolt."[65]

According to Pherecydes of Athens, during his battle with Zeus, Typhon first flees to the Caucasus, which begins to burn, then to the volcanic island of Pithecussae (modern Ischia), off the coast of Cumae, where he is buried under the island.[66] Apollonius of Rhodes (3rd century BC), like Pherecydes, presents a multi-stage battle, with Typhon being struck by Zeus' thunderbolt on mount Caucasus, before fleeing to the mountains and plain of Nysa, and ending up (as already mentioned by the fifth-century BC Greek historian Herodotus) buried under Lake Serbonis in Egypt.[67]

Like Pindar, Nicander has all the gods, but Zeus and Athena, transform into animal forms and flee to Egypt: Apollo became a hawk, Hermes an ibis, Ares a fish, Artemis a cat, Dionysus a goat, Heracles a fawn, Hephaestus an ox, and Leto a mouse.[68]

The geographer Strabo (c. 20 AD) gives several locations which were associated with the battle. According to Strabo, Typhon was said to have cut the serpentine channel of the Orontes River, which flowed beneath the Syrian Mount Kasios (modern Jebel Aqra), while fleeing from Zeus,[69] and some placed the battle at Catacecaumene ("Burnt Land"),[70] a volcanic plain, on the upper Gediz River, between the ancient kingdoms of Lydia, Mysia and Phrygia, near Mount Tmolus (modern Bozdağ) and Sardis the ancient capital of Lydia.[71]

In the versions of the battle given by Hesiod, Aeschylus and Pindar, Zeus' defeat of Typhon is straightforward, however a more involved version of the battle is given by Apollodorus.[72] No early source gives any reason for the conflict, but Apollodorus' account seemingly implies that Typhon had been produced by Gaia to avenge the destruction, by Zeus and the other gods, of the Giants, a previous generation of offspring of Gaia. According to Apollodorus, Typhon, "hurling kindled rocks", attacked the gods, "with hissings and shouts, spouting a great jet of fire from his mouth." Seeing this, the gods transformed into animals and fled to Egypt (as in Pindar and Nicander). However "Zeus pelted Typhon at a distance with thunderbolts, and at close quarters struck him down with an adamantine sickle"[73] Wounded, Typhon fled to the Syrian Mount Kasios, where Zeus "grappled" with him. But Typhon, twining his snaky coils around Zeus, was able to wrest away the sickle and cut the sinews from Zeus' hands and feet. Typhon carried the disabled Zeus across the sea to the Corycian cave in Cilicia where he set the she-serpent Delphyne to guard over Zeus and his severed sinews, which Typhon had hidden in a bearskin. But Hermes and Aegipan (possibly another name for Pan)[74] stole the sinews and gave them back to Zeus. His strength restored, Zeus chased Typhon to mount Nysa, where the Moirai tricked Typhon into eating "ephemeral fruits" which weakened him. Typhon then fled to Thrace, where he threw mountains at Zeus, which were turned back on him by Zeus' thunderbolts, and the mountain where Typhon stood, being drenched with Typhon's blood, became known as Mount Haemus (Bloody Mountain). Typhon then fled to Sicily, where Zeus threw Mount Etna on top of Typhon burying him, and so finally defeated him.

Oppian (2nd century AD) says that Pan helped Zeus in the battle by tricking Typhon to come out from his lair, and into the open, by the "promise of a banquet of fish", thus enabling Zeus to defeat Typhon with his thunderbolts.[75]

Nonnus's Dionysiaca

The longest and most involved version of the battle appears in Nonnus's Dionysiaca (late 4th or early 5th century AD).[76] Zeus hides his thunderbolts in a cave, so that he might seduce the maiden Plouto, and so produce Tantalus. But smoke rising from the thunderbolts, enables Typhon, under the guidance of Gaia, to locate Zeus's weapons, steal them, and hide them in another cave.[77] Immediately Typhon extends "his clambering hands into the upper air" and begins a long and concerted attack upon the heavens.[78] Then "leaving the air" he turns his attack upon the seas.[79] Finally Typhon attempts to wield Zeus' thunderbolts, but they "felt the hands of a novice, and all their manly blaze was unmanned."[80]

Now Zeus' sinews had somehow – Nonnus does not say how or when — fallen to the ground during their battle, and Typhon had taken them also.[81] But Zeus devises a plan with Cadmus and Pan to beguile Typhon.[82] Cadmus, desguised as a shepherd, enchants Typhon by playing the panpipes, and Typhon entrusting the thuderbolts to Gaia, sets out to find the source of the music he hears.[83] Finding Cadmus, he challenges him to a contest, offering Cadmus any goddess as wife, excepting Hera whom Typhon has reserved for himself.[84] Cadmus then tells Typhon that, if he liked the "little tune" of his pipes, then he would love the music of his lyre – if only it could be strung with Zeus' sinews.[85] So Typhon retrieves the sinews and gives them to Cadmus, who hides them in another cave, and again begins to play his bewitching pipes, so that "Typhoeus yielded his whole soul to Cadmos for the melody to charm".[86]

With Typhon distracted, Zeus takes back his thunderbolts. Cadmus stops playing, and Typhon, released from his spell, rushes back to his cave to discover the thunderbolts gone. Incensed Typhon unleashes devastation upon the world: animals are devoured, (Typhon's many animal heads each eat animals of its own kind), rivers turned to dust, seas made dry land, and the land "laid waste".[87]

The day ends with Typhon yet unchallenged, and while the other gods "moved about the cloudless Nile", Zeus waits through the night for the coming dawn.[88] Victory "reproaches" Zeus, urging him to "stand up as champion of your own children!"[89] Dawn comes and Typhon roars out a challenge to Zeus.[90] And a cataclysmic battle for "the sceptre and throne of Zeus" is joined. Typhon piles up mountains as battlements and with his "legions of arms innumerable", showers volley after volley of trees and rocks at Zeus, but all are destroyed, or blown aside, or dodged, or thrown back at Typhon. Typhon throws torrents of water at Zeus' thunderbolts to quench them, but Zeus is able to cut off some of Typhon's hands with "frozen volleys of air as by a knife", and hurling thunderbolts is able to burn more of typhon's "endless hands", and cut off some of his "countless heads". Typhon is attacked by the four winds, and "frozen volleys of jagged hailstones."[91] Gaia tries to aid her burnt and frozen son.[92] Finally Typhon falls, and Zeus shouts out a long stream of mocking taunts, telling Typhon that he is to be buried under Sicily's hills, with a cenotaph over him which will read "This is the barrow of Typhoeus, son of Earth, who once lashed the sky with stones, and the fire of heaven burnt him up".[93]

Etna and Ischia

Most accounts have the defeated Typhon buried under either Mount Etna in Sicily, or the volcanic island of Ischia, the largest of the Phlegraean Islands off the coast of Naples, with Typhon being the cause of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes.

Though Hesiod has Typhon simply cast into Tartarus by Zeus, some have read a reference to Mount Etna in Hesiod's description of Typhon's fall:

And flame shot forth from the thunderstricken lord in the dim rugged glens of the mount when he was smitten. A great part of huge earth was scorched by the terrible vapor and melted as tin melts when heated by men's art in channelled crucibles; or as iron, which is hardest of all things, is shortened by glowing fire in mountain glens and melts in the divine earth through the strength of Hephaestus. Even so, then, the earth melted in the glow of the blazing fire.[94]

The first certain references to Typhon buried under Etna, as well as being the cause of its eruptions, occur in Pindar:

Son of Cronus, you who hold Aetna, the wind-swept weight on terrible hundred-headed Typhon,[95]

and:

among them is he who lies in dread Tartarus, that enemy of the gods, Typhon with his hundred heads. Once the famous Cilician cave nurtured him, but now the sea-girt cliffs above Cumae, and Sicily too, lie heavy on his shaggy chest. And the pillar of the sky holds him down, snow-covered Aetna, year-round nurse of bitter frost, from whose inmost caves belch forth the purest streams of unapproachable fire. In the daytime her rivers roll out a fiery flood of smoke, while in the darkness of night the crimson flame hurls rocks down to the deep plain of the sea with a crashing roar. That monster shoots up the most terrible jets of fire; it is a marvellous wonder to see, and a marvel even to hear about when men are present. Such a creature is bound beneath the dark and leafy heights of Aetna and beneath the plain, and his bed scratches and goads the whole length of his back stretched out against it.[96]

Thus Pindar has Typhon in Tartarus, and buried under not just Etna, but under a vast volcanic region stretching from Sicily to Cumae (in the vicinity of modern Naples), a region which presumably also included Mount Vesuvius, as well as Ischia.[97]

Many subsequent accounts mention either Etna[98] or Ischia.[99] In Prometheus Bound, Typhon is imprisoned underneath Etna, while above him Hephaestus "hammers the molten ore", and in his rage, the "charred" Typhon causes "rivers of fire" to pour forth. Ovid has Typhon buried under all of Sicily, with his left and right hands under Pelorus and Pachynus, his feet under Lilybaeus, and his head under Etna; where he "vomits flames from his ferocious mouth". And Valerius Flaccus has Typhon's head under Etna, and all of Sicily shaken when Typhon "struggles". Lycophron has both Typhon and Giants buried under the island of Ischia. Virgil, Silius Italicus and Claudian, all calling the island "Inarime", have Typhon buried there. Strabo, calling Ischia "Pithecussae", reports the "myth" that Typhon lay buried there, and that when he "turns his body the flames and the waters, and sometimes even small islands containing boiling water, spout forth."[100]

In addition to Typhon, other mythological beings were also said to be buried under Mount Etna and the cause of its volcanic activity. Most notably the Giant Enceladus was said to be entombed under Etna, the volcano's eruptions being the breath of Enceladus, and its tremors caused by the Giant rolling over from side to side beneath the mountain.[101] Also said to be buried under Etna were the Hundred-hander Briareus,[102] and Asteropus who was perhaps one of the Cyclopes.[103]

Boeotia

Typhon's final resting place was apparently also said to be in Boeotia.[104] The Hesiodic Shield of Heracles names a mountain near Thebes Typhaonium, perhaps reflecting an early tradition which also had Typhon buried under a Boeotian mountain.[105] And some apparently claimed that Typhon was buried beneath a mountain in Boeotia, from which came exhalations of fire.[106]

"Couch of Typhoeus"

Homer describes a place he calls the "couch [or bed] of Typhoeus", which he locates in the land of the Arimoi (εἰν Ἀρίμοις), where Zeus lashes the land about Typhoeus with his thunderbolts.[107] Presumably this is the same land where, according to Hesiod, Typhon's mate Echidna keeps guard "in Arima" (εἰν Ἀρίμοισιν).[108]

But neither Homer nor Hesiod say anything more about where these Arimoi or this Arima might be. The question of whether an historical place was meant, and its possible location, has been, since ancient times, the subject of speculation and debate.[109]

Strabo discusses the question in some detail.[110] Several locales, Cilicia, Syria, Lydia, and the island of Ischia, all places associated with Typhon, are given by Strabo as possible locations for Homer's "Arimoi".

Pindar has his Cilician Typhon slain by Zeus "among the Arimoi",[111] and the historian Callisthenes (4th century BC), located the Arimoi and the Arima mountains in Cilicia, near the Calycadnus river, the Corycian cave and the Sarpedon promomtory.[112] The b scholia to Iliad 2.783, mentioned above, says Typhon was born in Cilicia "under Arimon",[113] and Nonnus mentions Typhon's "bloodstained cave of Arima" in Cilicia.[114]

Just across the Gulf of Issus from Corycus, in ancient Syria, was Mount Kasios (modern Jebel Aqra) and the Orontes River, sites associated with Typhon's battle with Zeus,[115] and according to Strabo, the historian Posidonius (c. 2nd century BC) identified the Arimoi with the Aramaeans of Syria.[116]

Alternatively, according to Strabo, some placed the Arimoi at Catacecaumene,[117] while Xanthus of Lydia (5th century BC) added that "a certain Arimus" ruled there.[118] Strabo also tells us that for "some" Homer's "couch of Typhon" was located "in a wooded place, in the fertile land of Hyde", with Hyde being another name for Sardis (or its acropolis), and that Demetrius of Scepsis (2nd century BC) thought that the Arimoi were most plausibly located "in the Catacecaumene country in Mysia".[119] The 3rd-century BC poet Lycophron placed the lair of Typhons' mate Echidna in this region.[120]

Another place, mentioned by Strabo, as being associated with Arima, is the island of Ischia, where according to Pherecydes of Athens, Typhon had fled, and in the area where Pindar and others had said Typhon was buried. The connection to Arima, comes from the island's Greek name Pithecussae, which derives from the Greek word for monkey, and according to Strabo, residents of the island said that "arimoi" was also the Etruscan word for monkeys.[121]

Name

Typhon's name has a number of variants.[122] The earliest forms,Typhoeus and Typhaon, occur prior to the 5th century BC. Homer uses Typhoeus,[123] Hesiod and the Homeric Hymn to Apollo use both Typhoeus and Typhaon.[124] The later forms Typhos and Typhon occur from the 5th century BC onwards, with Typhon becoming the standard form by the end of that century.

Though several possible derivations of the name Typhon have been suggested, the derivation remains uncertain.[125] Consistent with Hesiod's making storm winds Typhon's offspring, some have supposed that Typhon was originally a wind-god, and ancient sources associated him with the Greek words tuphon, tuphos meaning "whirlwind".[126] Other theories include derivation from a Greek root meaning "smoke" (consistent with Typhon's identification with volcanoes),[127] from an Indo-European root (*dhuH-) meaning "abyss" (making Typhon a "Serpent of the Deep"),[128][129] and from Sapõn the Phoenician name for the Ugaritic god Baal's holy mountain Jebel Aqra (the classical Mount Kasios) associated with the epithet Baʿal Sapōn.[130]

The name may have influenced the Persian word tūfān which is a source of the meteorological term typhoon.[131]

Comparative mythology

Succession myth

The Typhonomachy—Zeus' battle with, and defeat of Typhon—is just one part of a larger "Succession Myth" given in Hesiod's Theogony.[132] The Hesiodic succession myth describes how Uranus, the original ruler of the cosmos, hid his offspring away inside Gaia, but was overthrown by his Titan son Cronus, who castrated Uranus, and how in turn, Cronus, who swallowed his children as they were born, was himself overthrown by his son Zeus, whose mother had given Cronus a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes to swallow, in place of Zeus. However Zeus is then confronted with one final adversary, Typhon, which he quickly defeats. Now clearly the supreme power in the cosmos, Zeus is elected king of gods. Zeus then establishes and secures his realm through the apportionment of various functions and responsibilities to the other gods, and by means of marriage. Finally, by swallowing his first wife Metis, who was destined to produce a son stronger than himself, Zeus is able to put an end to the cycle of succession.

Python

Typhon's story seems related to that of another monstrous offspring of Gaia: Python, the serpent killed by Apollo at Delphi,[133] suggesting a possible common origin.[134] Besides the similarity of names, their shared parentage, and the fact that both were snaky monsters killed in single combat with an Olympian god, there are other connections between the stories surrounding Typhon, and those surrounding Python.[135]

Although the Delphic monster killed by Apollo is usually said to be the male serpent Python, in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, the earliest account of this story, the god kills a nameless she-serpent (drakaina), subsequently called Delphyne, who had been Typhon's foster-mother.[136] Delphyne and Echidna, besides both being intimately connected to Typhon—one as mother, the other as mate—share other similarities.[137] Both were half-maid and half-snake,[138] a plague to men,[139] and associated with the Corycian cave in Cilicia.[140]

Python was also perhaps connected with a different Corycian Cave than the one in Cilicia, this one on the slopes of Parnassus above Delphi, and just as the Corycian cave in Cilicia was thought to be Typhon and Echidna's lair, and associated with Typhon's battle with Zeus, there is evidence to suggest that the Corycian cave above Delphi was supposed to be Python's (or Delphyne's) lair, and associated with his (or her) battle with Apollo.[141]

Near Eastern influence

From at least as early as Pindar, and possibly as early as Homer and Hesiod (with their references to the Arimoi and Arima), Typhon's birthplace and battle with Zeus were associated with various Near East locales in Cilicia and Syria, including the Corycian Cave, Mount Kasios, and the Orontes River. Besides this coincidence of place, the Hesiodic succession myth, (including the Typhonomachy), as well as other Greek accounts of these myths, exhibit other parallels with several ancient Near Eastern antecedents, and it is generally held that the Greek accounts are intimately connected with, and influenced by, these Near Eastern counterparts.[142] In particular, the Typhonomachy is generally thought to have been influenced by several Near Eastern monster-slaying myths.[143]

Mesopotamia

Three related god vs. monster combat myths from Mesopotamia, date from at least the early second-millennium BC or earlier. These are the battles of the god Ninurta with the monsters Asag and Anzu, and the god Marduk's battle with the monstrous Tiamat.

Ninurta vs. Asag

Lugal-e, a late-third-millennium BC Sumerian poem, tells the story of the battle between the Mesopotamian hero-god Ninurta and the terrible monster Asag.[144] Like Typhon, Asag was a monstrous hissing offspring of Earth (Ki), who grew mighty and challenged the rule of Ninurta, who like Zeus, was a storm-god employing winds and floods as weapons. As in Hesiod's account of the Typhonomachy, during their battle, both Asag and Ninurta set fire to the landscape. And like Apollodorus' Typhon, Asag evidently won an initial victory, before being finally overcome by Ninurta.

Ninurta vs. Anzu

The early second millennium BC Akkadian epic Anzu tells the story of another combat of Ninurta with a monstrous challenger.[145] This second foe is the winged monster Anzu, another offspring of Earth. Like Hesiod's Typhon, Anzu roared like a lion,[146] and was the source of destructive storm winds. Ninurta destroys Anzu on a mountainside, and is portrayed as lashing the ground where Anzu lay with a rainstorm and floodwaters, just as Homer has Zeus lash the land about Typhon with his thunderbolts.[147]

Marduk vs. Tiamat

The early second-millennium BC Babylonian-Akkadian creation epic Enûma Eliš tells the story of the battle of the Babylonian supreme god Marduk with Tiamat, the Sea personified.[148] Like Zeus, Marduk was a storm-god, who employed wind and lightning as weapons, and who, before he can succeed to the kingship of the gods, must defeat a huge and fearsome enemy in single combat.[149] This time the monster is female, and may be related to the Pythian dragoness Delphyne,[150] or Typhon's mate Echidna, since like Echidna, Tiamat was the mother of a brood of monsters.[151]

Mount Kasios

Like the Typhonomachy, several Near East myths, tell of battles between a storm-god and a snaky monster associated with Mount Kasios, the modern Jebel Aqra. These myths are usually considered to be the origins of the myth of Zeus's battle with Typhon.[152]

Baal Sapon vs. Yamm

From the south side of the Jebel Aqra, comes the tale of Baal Sapon, and Yamm, the deified Sea (like Tiamat above). Fragmentary Ugaritic tablets, dated to the fourteenth or thirteenth-century BC, tell the story of the Canaanite storm-god Baal Sapon's battle against the monstrous Yamm on Mount Sapuna the Canaanite name for later Greeks’ Mount Kasios. Baal defeats Yamm with two throwing clubs (thunderbolts?) named ‘Expeller’ and ‘Chaser’, which fly like eagles from the storm-god's hands. Other tablets associate the defeat of the snaky Yamm with the slaying of a seven headed serpent ‘’Ltn’’ (Litan/Lotan), apparently corresponding to the biblical Leviathan.[153]

Tarhunna vs. Illuyanka

From the north side of the Jebel Aqra, come Hittite myths, c. 1250 BC, which tell two versions of the storm-god Tarhunna’s (Tarhunta’s) battle against the serpent Illuyanka(s).[154] In both of these versions, Tarhunna suffers an initial defeat against Illuyanka. In one version, Tarhunna seeks help from the goddess Inara, who lures Illuyanka from his lair with a banquet, thereby enabling Tarhunna to surprise and kill Illuyanka. In the other version Illuyanka steals the heart and eyes of the defeated god, but Tarhunna’s son marries a daughter of Illuyanka and is able to retrieve Tarhunna’s stolen body parts, whereupon Tarhunna kills Illuyanka.

These stories particularly resemble details found in the accounts of the Typhonomachy of Apollodorus, Oppian and Nonnus, which, though late accounts, possible preserve much earlier ones:[155] The storm-god’s initial defeat (Apollodorus, Nonnus), the loss of vital body parts (sinews: Apollodorus, Nonnus), the help of allies (Hermes and Aegipan: Apollodorus; Cadmos and Pan: Nonnus; Pan: Oppian), the luring of the serpentine opponent from his lair through the trickery of a banquet (Oppian, or by music: Nonnus).

Teshub vs. Hedammu and Ullikummi

Another c. 1250 BC Hittite text, derived from the Hurrians, tells of the Hurrian storm-god Teshub (with whom the Hittite's Tarhunna came to be identified) who lived on Mount Hazzi, the Hurrian name for the Jebel Aqra, and his battle with the sea-serpent Hedammu. Again the storm-god is aided by a goddess Sauska (equivalent to Inaru), who this time seduces the monster with music (as in Nonnus), drink, and sex, successfully luring the serpent from his lair in the sea.[156] Just as the Typhonomachy can be seen as a sequel to the Titanomachy, a different Hittite text derived from the Hurrians, The Song of Ullikummi, a kind of sequel to the Hittite "kingship in heaven" succession myths of which the story of Teshub and Hedammu formed a part, tells of a second monster, this time made of stone, named Ullikummi that Teshub must defeat, in order to secure his rule.[157]

Set

From apparently as early as Hecataeus of Miletus (c. 550 BC – c. 476 BC), Typhon was identified with Set, the Egyptian god of chaos and storms.[158] This syncretization with Egyptian mythology can also be seen in the story, apparently known as early as Pindar, of Typhon chasing the gods to Egypt, and the gods transforming themselves into animals.[159] Such a story arose perhaps as a way for the Greeks to explain Egypt's animal-shaped gods.[160] Herodotus also identified Typhon with Set, making him the second to last divine king of Egypt. Herodotus says that Typhon was deposed by Osiris' son Horus, whom Herodutus equates with Apollo (with Osiris being equated with Dionysus),[161] and after his defeat by Horus, Typhon was "supposed to have been hidden" in the "Serbonian marsh" (identified with modern Lake Bardawil) in Egypt.[162]

Confused with the Giants

Typhon bears a close resemblance to an older generation of descendants of Gaia, the Giants.[163] They, like their younger brother Typhon after them, challenged Zeus for supremacy of the cosmos,[164] were (in later representations) shown as snake-footed,[165] and end up buried under volcanos.[166]

While distinct in early accounts, in later accounts Typhon was often considered to be one of the Giants.[167] The Roman mythographer Hyginus (64 BC – 17 AD) includes Typhon in his list of Giants,[168] while the Roman poet Horace (65 – 8 BC), mentions Typhon, along with the Giants Mimas, Porphyrion, and Enceladus, as together battling Athena, during the Gigantomachy.[169] The Astronomica, attributed to the 1st-century AD Roman poet and astrologer Marcus Manilius,[170] and the late 4th-century early 5th-century Greek poet Nonnus, also consider Typhon to be one of the Giants.[171]

Notes

- Ogden 2013a, p. 69; Gantz, p. 50; LIMC Typhon 14.

- Hesiod,Theogony 820–822. Apollodorus, 1.6.3, and Hyginus, Fabulae Preface also have Typhon as the offspring of Gaia and Tartarus. However Hyginus, Fabulae 152 has Typhon as the offspring of Tartarus and Tartara, where, according to Fontenrose, p. 77, Tartara was "no doubt [Gaia] herself under a name which designates all that lies beneath the earth."

- Apollodorus, 1.6.3.

- Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes 522–523; Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 353; Nicander, apud Antoninus Liberalis 28; Virgil, Georgics 1. 278–279; Ovid, Metamorphoses 5.321–331; Manilius, Astronomica 2.874–875 (pp. 150, 153); Lucan, Pharsalia 4.593–595; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.154–155 (I pp. 14–15).

- Homeric Hymn to Apollo 305–355; Fontenrose, p. 72; Gantz, p. 49. Stesichorus (c. 630 – 555 BC), it seems, also had Hera produce Typhon alone to "spite Zeus", see Fragment 239 (Campbell, pp. 166–167); West 1966, p. 380; but see Fontenrose, p. 72 n. 5.

- As for Typhon being a bane to mortals, Gantz, p. 49, remarks on the strangeness of such a description for one who would challenge the gods.

- Pindar, Pythian 8.15–16.

- Pindar, Pythian 1.15–17.

- Fontenrose, pp. 72–73; West 1966, p. 251 line 304 εἰν Ἀρίμοισιν (c).

- Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 353–356; Gantz, p. 49.

- Apollodorus, 1.6.3; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.140. (I pp. 12–13), 1.154. (I pp. 14–15), 1.258–260 (I pp. 20–23), 1.321 (I pp. 26–27), 2.35 (I pp. 46–47), 2.631 ff. (I pp. 90–91).

- Kirk, Raven, and Schofield. pp. 59–60 no. 52; Ogden 2013b, pp. 36–38; Fontenrose, p. 72; Gantz, pp. 50–51, Ogden 2013a, p. 76 n. 46.

- Hesiod, Theogony 306–307.

- Hesiod, Theogony 823–835.

- Homeric Hymn to Apollo 306, 351–352. Gantz, p. 49, speculates that Typhon being given to the Python to raise "might suggest a resemblance to snakes".

- Pindar, Pythian 1.16, 8.16, Olympian 4.6–7.

- Pindar, fragment 93 apud Strabo, 13.4.6 (Race, pp. 328–329).

- Ogden 2013a, p. 71; e.g. Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 355; Aristophanes, Clouds 336; Hyginus, Fabulae 152, Oppian, Halieutica 3.15–25 (pp. 344–347) .

- Ogden 2013a, p. 69; Gantz, p. 50; Munich Antikensammlung 596 = LIMC Typhon 14.

- Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes 511.

- Nicander, apud Antoninus Liberalis 28; Gantz, p. 50.

- Ogden 2013a, p. 72.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.187 (I pp. 16–17).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.30, 36 (I pp. 46–47), 2.141 (I pp. 54–55).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.173 (I pp. 16–17), 2.32 (I pp. 46–47)

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.218 (I pp. 18–19).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.508–509 (I pp. 38–41).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.31–33 (I pp. 46–47).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.141–142 (I pp. 54–55).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.243 (I pp. 62–63).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.154–162 (I pp. 14–15).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.444–256 (I pp. 62–65).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.381 (I pp. 72–73); also 2.244 (I pp. 62–63) ("many-armed Typhoeus").

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 3.301; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.297 (I pp. 24–25), 2.343 (I pp. 70–71), 2.621 (I pp. 90–91).

- Hesiod, Theogony 306–314. Compare with Lycophron, Alexandra 1351 ff. (pp. 606–607), which refers to Echidna as Typhon's spouse (δάμαρ).

- Apollodorus, Library 2.5.10 also has Orthrus as the offspring of Typhon and Echidna. Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica (or Fall of Troy) 6.249–262 (pp. 272–273) has Cerberus as the offspring of Typhon and Echidna, and Orthrus as his brother.

- Acusilaus, fr. 13 Fowler (Fowler 2000, p. 11; Freeman, p. 15 fragment 6), Hyginus, Fabulae Preface, 151, and Quintus Smyrnaeus, loc. cit., also have Cerberus as the offspring of Typhon and Echidna. Bacchylides, Ode 5.62, Sophocles, Women of Trachis 1097–1099, Callimachus, fragment 515 Pfeiffer (Trypanis, pp. 258–259), Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.500–501, 7.406–409, all have Cerberus as the offspring of Echidna, with no father named.

- Hyginus, Fabulae Preface, 30 (only Typhon is mentioned), 151 also has the Hydra and as the offspring of Echidna and Typhon.

- Hesiod, Theogony, 319. The referent of the "she" in line 319 is uncertain, see Gantz, p. 22; Clay, p. 159, with n. 34.

- Acusilaus, fr. 13 Fowler (Fowler 2000, p. 11; Freeman, p. 15 fragment 6); Fowler 2013, p. 28; Gantz, p. 22; Ogden 2013a, pp. 149–150.

- Pherecydes of Athens, fr. 7 Fowler (Fowler 2000, p. 278); Fowler 2013, pp. 21, 27–28; Gantz, p. 22; Ogden 2013a, pp. 149–150.

- Pherecydes of Athens, fr. 16b Fowler (Fowler 2000, p. 286); Hesiod, Theogony 333–336; Fowler 2013, p. 28; Ogden 2013a, p. 149 n. 3; Hošek, p. 678. The first to name the dragon Ladon is Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 4.1396 (pp. 388–389), which makes Ladon earthborn, see Fowler 2013, p. 28 n. 97. Tzetzes, Chiliades 2.36.360 (Kiessling, p. 54; English translation: Berkowitz, p. 33), also has Typhon as Ladon's father.

- Lasus of Hermione, fragment 706A (Campbell, pp. 310–311). Euripides, The Phoenician Women 1019–1020; Ogden 2013a, p. 149 n. 3 has Echidna as her mother, without mentioning a father. Hesiod mentions the Sphinx (and the Nemean lion) as having been the offspring of Echidna's son Orthrus, by another ambiguous "she", in line 326 (see Clay, p.159, with n. 34), read variously as the Chimera, Echidna herself, or even Ceto.

- Apollodorus, Library 2.5.10 (Orthrus), 2.3.1 (Chimera), 2.5.11 (Caucasian Eagle), 2.5.11 (Ladon), 3.5.8 (Sphinx), 2.5.1 (Nemean lion), Epitome 1.1 (Crommyonian Sow).

- Hyginus, Fabulae Preface, 151.

- Compare with Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 2.1208–1215 (pp. 184–185), where the dragon is the offspring of Gaia by Typhon (Hošek, p. 678).

- See also Virgil, Ciris 67; Lyne, pp. 130–131. Others give other parents for Scylla. Several authors name Crataeis as the mother of Scylla, see Homer, Odyssey 12.124–125; Ovid, Metamorphoses 13.749; Apollodorus, E7.20; Servius on Virgil Aeneid 3.420; and schol. on Plato, Republic 9.588c. Neither Homer nor Ovid mention a father, but Apollodorus says that the father was Trienus (or Triton?) or Phorcus, similarly the Plato scholiast, perhaps following Apollodorus, gives the father as Tyrrhenus or Phorcus, while Eustathius on Homer, Odyssey 12.85 gives the father as Triton. The Hesiodic Megalai Ehoiai (fr. 262 MW = Most 200) gives Hecate and Phorbas as the parents of Scylla, while Acusilaus, fr. 42 Fowler (Fowler 2013, p. 32) says that Scylla's parents were Hekate and Phorkys (so also schol. Odyssey 12.85). Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 4. 828–829 (pp. 350–351) says that "Hecate who is called Crataeis," and Phorcys were the parents of Scylla. Semos of Delos (FGrHist 396 F 22) says that Crataeis was the daughter of Hekate and Triton, and mother of Scylla by Deimos. Stesichorus, F220 PMG (Campbell, pp. 132–133) has Lamia as the mother of Scylla, possibly the Lamia who was the daughter of Poseidon. For discussions of the parentage of Scylla, see Fowler 2013, p. 32, Ogden 2013a, p. 134; Gantz, pp. 731–732; and Frazer's note to Apollodorus, E7.20.

- Hesiod, Theogony, 265–269; so also Apollodorus, 1.2.6, and Hyginus, Fabulae Preface (though Fabulae 14, gives their parents as Thaumas and Oxomene). In the Epimenides Theogony (3B7) they are the daughters of Oceanus and Gaia, while in Pherecydes of Syros (7B5) they are the daughters of Boreas (Gantz, p. 18).

- Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 4.428, 516.

- Hošek, p. 678; see Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica (or Fall of Troy) 12.449–453 (pp. 518–519), where they are called "fearful monsters of the deadly brood of Typhon".

- Hesiod, Theogony 869–880, which specifically excludes the winds Notus (South Wind), Boreas (North Wind) and Zephyr (West Wind) which he says are "a great blessing to men"; West 1966, p. 381; Gantz, p. 49; Ogden 2013a, p. 226.

- Fontenrose, pp. 70–76; West 1966, pp. 379–383; Lane Fox, pp. 283–301; Gantz, pp. 48–50; Ogden 2013a, pp. 73–80.

- Homer, Iliad 2.780–784, a reference, apparently, not to their original battle but to an ongoing "lashing" by Zeus of Typhon where he lies buried, see Fontenrose, pp. 70–72; Ogden 2013a, p. 76.

- Hesiod, Theogony 836–838.

- Hesiod, Theogony 839–852.

- Zeus' apparently easy victory over Typhon in Hesiod, in contrast to other accounts of the battle (see below), is consistent with, for example, what Fowler 2013, p. 27 calls "Hesiod's pervasive glorification of Zeus".

- Hesiod, Theogony 853–867.

- Hesiod, Theogony 868.

- Epimenides fr. 10 Fowler (Fowler 2000, p. 97); Ogden 2013a, p. 74; Gantz, p. 49; Fowler 2013, p. 27 n. 93.

- Griffiths, pp. 374–375; Pindar, fr. 91 SM apud Porphyry, On Abstinence From Animal Food 3.16 (Taylor, p. 111); Fowler 2013, p. 29; Ogden 2013a, p. 217; Gantz, p. 49; West 1966, p. 380; Fontenrose, p. 75.

- Pindar, Pythian 1.15–16.

- Pindar, Pythian 8.16–17.

- Pindar, Olympian 4.6–7.

- Pindar, Pythian 1.15–28; Gantz, p. 49.

- Gantz, p. 49; Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 356–364.

- Pherecydes of Athens, fr. 54 Fowler (Fowler 2000, p. 307); Fowler 2013, p. 29; Lane Fox, pp. 298–299; Ogden 2013a, p. 76 n. 47; Gantz, p. 50.

- Fowler 2013, p. 29; Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 2.1208–1215 (pp. 184–185); cf. Herodotus, 3.5.

- Nicander, apud Antoninus Liberalis 28.

- Strabo, 16.2.7; Ogden 2013a, p. 76.

- Strabo, 12.8.19, compare with Diodorus Siculus 5.71.2–6, which says that Zeus slew Typhon in Phrygia.

- Lane Fox, pp. 289–291, rejects Catacecaumene as the site of Homer's "Arimoi".

- Fontenrose, pp. 73–74; Lane Fox, pp. 287–288; Apollodorus, 1.6.3. Though a late account, Apollodorus may have drawn upon early sources, see Fontenrose, p. 74; Lane Fox, p. 287, Ogden 2013a, p. 78.

- Perhaps this was supposed to be the same sickle which Cronus used to castrate Uranus, see Hesiod, Theogony 173 ff.; Lane Fox, p. 288.

- Gantz, p. 50; Fontenros, p. 73; Smith, "Aegipan".

- Oppian, Halieutica 3.15–25 (pp. 344–347); Fontenrose, p. 74; Lane Fox, p. 287; Ogden 2013a, p. 74.

- Fontenrose, pp. 74–75; Lane Fox, pp. 286–288; Ogden 2013a, pp. 74– 75.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.145–164 (I pp. 12–15).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.164–257 (I pp. 14–21).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.258–293 (I pp. 20–25).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.294–320 (I pp. 24–27).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.510–512 (I pp. 40–41). Nonnus' account regarding the sinews is vauge and not altogether sensible since as yet Zeus and Typhon have not met, see Fontenrose, p. 75 n. 11 and Rose's note to Nonnus, Dionysiaca 510 pp. 40–41 n. b.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.363–407 (I pp. 28–33).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.409–426 (I pp. 32–35).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.427–480 (I pp. 34–37). For Typhon's plans to marry Hera see also 2.316–333 (I pp. 68–69), 1.581–586 (I pp. 86–87).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.481–481 (I pp. 38–39).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.507–534 (I pp. 38–41).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.1–93 (I pp. 44–51).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.163–169 (I pp. 56–57).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.205–236 (I pp. 60–63).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.244–355 (I pp. 62–71).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.356–539 (I pp. 72–85).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.540–552 (I pp. 84–85).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 2.553–630 (I pp. 84–91).

- Hesiod, Theogony 859–867. The reading of Etna here is doubted by West 1966, p. 393 line 860 ἀιδνῇς, though see Lane Fox, p. 346 with n. 63.

- Pindar, Olympian 4.6–7.

- Pindar, Pythian 1.15–28.

- Strabo, 5.4.9, 13.4.6; Lane Fox, p. 299, Ogden 2013a, p. 76; Gantz, p. 49. Though Pindar doesn't mention the island by name, Lane Fox, p. 299, argues that the "sea-girt cliffs above Cumae" mentioned by Pindar refer to the island cliffs of Ischia.

- Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound 353–374; Nicander, apud Antoninus Liberalis 28; Ovid, Fasti 4.491–492 (pp. 224–225), Metamorphoses 5.346 ff.; Valerius Flaccus, Argonautica 2.23 ff.; Manilius, Astronomica 2.879–880 (pp. 152, 153); Seneca, Hercules Furens 46–62 (pp. 52–53), Thyestes 808–809 (pp. 298–299) (where the Chorus asks if Typhon has thrown the mountain (presumably Etna) off "and stretched his limbs"); Apollodorus, 1.6.3; Hyginus, Fabulae 152; the b scholia to Iliad 2.783 (Kirk, Raven, and Schofield. pp. 59–60 no. 52); Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 5.16 (pp.498–501); Philostratus the Elder, Imagines 2.17.5 (pp. 198–201); Nonnus Dionysiaca 2.622–624 (I pp. 90–91) (buried under Sicily).

- Lycophron, Alexandra 688–693 (pp. 550–551); Virgil, Aeneid 9.715–716; Silius Italicus, Punica 8.540–541 (I pp. 432–433) (see also Punica 12.148–149 (II pp. 156–157), which has the Titan Iapetus also buried there); Claudian, Rape of Proserpine 3.183–184 (pp. 358–359); Strabo, 5.4.9 (Ridgway, David, pp. 35–36).

- Strabo, 5.4.9.

- Callimachus, fragment 117 (382) (pp. 342–343); Statius, Thebaid 11.8 (pp. 390–391); Aetna (perhaps written by Lucilius Junior), 71–73 (pp. 8–9); Apollodorus, 1.6.2; Virgil, Aeneid 3.578 ff. (with Conington's note to 3.578); Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 5.16 (pp. 498–501); Claudian, Rape of Proserpine 1.153–159 (pp. 304–305), 2.151–162 (pp. 328–331), 3.186–187 (pp. 358–359); Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica (or Fall of Troy) 5.641–643 (pp. 252–253), 14.582–585 (pp. 606–607). Philostratus the Elder, Imagines 2.17.5 (pp. 198–201) has Enceladus buried in Italy rather than Sicily.

- Callimachus, Hymn 4 (to Delos) 141–146 (pp. 96, 97); Mineur. p. 153.

- Euphorion of Chalcis, fr. 71.11.

- Fontenrose, pp. 78–79; Fowler 2013, p. 29.

- Hesiod, Shield of Heracles 32–33; compare with Dio Chrysostom, 1.67, who speaks of a mountain peak near Thebes named for Typhon. See also Tzetzes on Lycophron Alexandra 177. For other sources see Fontenrose, pp.78–79; Fowler 2013, p. 29.

- Fontenrose, p. 79, who theorizres that, while there are no volcanoes in Boeotia, if any credence can be given to such accounts, these fiery exhalations (anadoseis) "were probably ground-fires such as are attested near Trapezos on the lower slopes of Mount Lykaion in Arcadia", see Pausanias, 8.29.1.

- Homer, Iliad 2.783.

- Hesiod, Theogony 295–305. Fontenrose, pp. 70–72; West 1966, pp. 250–251 line 304 εἰν Ἀρίμοισιν; Lane Fox, p. 288; Ogden 2013a, p. 76; Fowler 2013, pp. 28–29. West, notes that Typhon's "couch" appears to be "not just 'where he lies', but also where he keeps his spouse"; compare with Quintus Smyrnaeus, 8.97–98 (pp. 354–355).

- For an extensive discussion see Lane Fox, especially pp. 39, 107, 283–301; 317–318. See also West 1966, pp. 250–251 line 304 εἰν Ἀρίμοισιν; Ogden 2013a, p. 76; Fowler 2013, pp. 28–30.

- Strabo, 13.4.6.

- Pindar, fragment 93 apud Strabo, 13.4.6 (Race, pp. 328–329).

- Callisthenes FGrH 124 F33 = Strabo, 13.4.6; Ogden 2013a, p. 76; Ogden 2013b, p. 25; Lane Fox, p. 292. Lane Fox, pp. 292–298, connects Arima with the Hittite place names "Erimma" and "Arimmatta" which he associates with the Corycian cave.

- Kirk, Raven, and Schofield. pp. 59–60 no. 52; Ogden 2013b, pp. 36–38; Gantz, pp. 50–51, Ogden 2013a, p. 76 n. 46.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.140. (I pp. 12–13).

- Strabo, 16.2.7; Apollodorus, 1.6.3; Ogden 2013a, p. 76.

- Strabo, 16.4.27. According to West 1966, p. 251, "This identification [Arimoi as Aramaeans] has been repeated in modern times." For example for Fontenrose, p. 71, the "Arimoi, it seems fairly certain, are the Aramaeans, and the country is either Syria or Cilicia, most likely the latter, since in later sources that is usually Typhon's land." But see Fox Lane, pp. 107, 291–298, which rejects this identification, instead arguing for the derivation of "Arima" from the Hittite place names "Erimma" and "Arimmatta".

- Strabo, 12.8.19.

- Strabo, 13.4.11.

- Strabo, 13.4.6. For Hyde see also Homer, Iliad 20.386.

- Lycophron, Alexandra 1351 ff. (pp. 606–607) associates Echidna's "dread bed" with a lake identified as Lake Gygaea or Koloe (modern Lake Marmara), see Robert, pp. 334 ff.; Lane Fox, pp. 290–291. For Lake Gygaea see Homer, Iliad 2.864–866; Herodotus, 1.93; Strabo, 13.4.5–6.

- Strabo, 13.4.6; Lane Fox, pp. 298–301; Ogden 2013a, p. 76 n. 47; Fowler 2013, p. 29.

- Ogden 2013a, p. 152; Fontenrose, p. 70.

- Homer, Iliad 2.782, 783.

- Hesiod, Theogony 306 (Typhaon), 821 (Typhoeus), 869 (Typhoeus); Homeric Hymn to Apollo 306 (Typhaon), 352 (Typhaon), 367 (Typhoeus).

- Fontenrose, p. 546; West 1966, p. 381; Lane Fox, 298, p. 405, p. 407 n. 53; Ogden 2013a, pp. 152–153. Fontenrose: "His name is very likely not Greek; but though non-Hellenic etymologies have been suggested, I doubt that its meaning is now recoverable"; West: "The origin of the name and its variant forms is unexplained"; Lane Fox: "a name of uncertain derivation". Given that Typhoeus and Typhaon are apparently the earlier forms, Ogden, suggests that theories based upon the assumption that "Typhon" is the primary form "seem ill-founded", and says that it "seems much more likely" that the form Typhon arose from "the desire to assimilate this drakōn's name to the name shape of other drakontes, perhaps Python in particular".

- West 1966, pp. 252, 381; Ogden 2013a, p. 152, both citing Worms 1953. But according to West "it is far from certain that there is any real etymological connection ... [Typhon's] association with the tornado is secondary, and due to popular etymology. It may have already influenced Hesiod, for there is at present no better explanation of the fact that irregular stormwinds (especially those met at sea) are made the children of [Typhon]." For the use of the words τῡφώς, τῡφῶν meaning "whirlwind" see LSJ, Τυ_φώς , ῶ, ὁ; Suda s.v. Tetuphômai, Tuphôn, Tuphôs; Aeschylus, Agamemnon 656; Aristophanes, Frogs 848, Lysistrata, 974; Sophocles, Antigone 418.

- Fontenrose, p. 546 with n. 2; Lane Fox, p. 298, which offers the derivation of Typhon from the Greek τῡφῶν tūphōn ("smoking", "smouldering"), though Ogden 2013a, p. 153, while conceding that such a derivation "fits Typhon's nature and condition in life and death so perfectly", objects (n. 23) "why would the participle-style declension in –ων, –οντος have been substituted with one in –ῶν, –ῶνος?"

- Watkins, pp. 460–463; Ogden 2013a, pp. 152–153.

- R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1522.

- Supported, with caveats, by West 1997, p. 303: "Here, then, we have a divinity [Baʿal Zaphon] with a name which might indeed have become "Typhon" in Greek", but rejected by Lane Fox, p. 298. See also Fontenrose, p. 546 n. 2; West 1966, p. 252; Ogden 2013a, p. 153, with n. 22.

- The Arabic Contributions to the English Language: An Historical Dictionary by Garland Hampton Cannon and Alan S. Kaye considers typhoon "a special case, transmitted by Cantonese, from Arabic, but ultimately deriving from Greek. [...] The Chinese applied the [Greek] concept to a rather different wind [...]"

- West 1966, pp. 18–19; West 1997, pp. 276–278.

- For a discussion of Python, see Ogden 2013a, pp. 40–48; Fontenrose, especially pp. 13–22. For Python's parentage, see Fontenrose, p. 47; Euripides, Iphigenia in Tauris 1244–1248; Hyginus, Fabulae 152; Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.434–438.

- Fontenrose, pp. 77, with n. 1, 193; Watkins, p. 462.

- For an extensive discussion of the similarities, see Fontenrose, pp. 77–93; see also Kerenyi, pp. 26–28, 136.

- Hymn to Apollo (3) 300–306, 349–369; Ogden 2013a, pp. 40 ff.; Gantz, p. 88; Fontenrose, pp. 14–15; p. 94. Apollodorus, 1.6.3, for example, calls her Delphyne.

- Fontenrose, pp. 94–97 argues that Echidna and Delphyne (along with Ceto and possibly Scylla) were different names for the same creature.

- Apollodorus, 1.6.3 calls Delphyne both a drakaina and a "half-bestial maiden"; see Ogden 2013a, p. 44, Fontenrose, p. 95.

- Hymn to Apollo (3) 300–304; see Fontenrose, p. 14.

- According to Apollodorus, 1.6.3, Typhon set Delphyne as guard over Zeus' severed sinews in the Corycian cave; see Ogden, 2013a, p. 42; Fontenrose, p. 94.

- Fontenrose, pp. 78; 407–412.

- West 1966, pp. 19–31; Burkert, pp. 19–24; Penglase, especially pp. 1—2, 152, 156–165, 199–205; West 1997, pp. 276–305; Lane Fox, pp. 242–314.

- Fontenrose, p. 145; West 1966, pp. 379–380 lines 820-80 Typhoeus, 391–392 line 853; Penglase, pp. 87–88, 152, 156–157, 159, 161–165; Watkins, pp. 448–459; West 1997, pp. 303–304; Lane Fox 2010, pp. 283 ff.; Ogden 2013a, pp. 14–15, 75.

- Fontenrose, pp. 146–147, 151, 152, 155, 161; Penglase, pp. 54–58; 163, 164; West 1997, p. 301; Ogden 2013a, pp. 11, 78.

- Penglase, pp. 44–47; West 1997, pp. 301–302; Ogden 2013a, p. 78; Dalley 1989 (2000) pp. 222 ff..

- West 1997, p. 301.

- West 1997, p. 301.

- Fontenrose, pp. 148–151; West 1966, pp. 22–24; West 1997, pp. 67–68, 280–282; Ogden 2013a, pp. 11–12.

- Fontenrose, pp. 150, 158; West 1966, pp. 23–24; West 1997, pp. 282, 302.

- Penglase, pp. 87–88.

- Fontenrose, pp. 149, 152; West 1966, pp. 244, 379; West 1997, p. 468. Although Gaia's attitude toward Zeus in Hesiod's Theogony is mostly benevolent: protecting him as a child (479 ff.), helping him to defeat the Titans (626–628), advising him to swallow Metis, thereby protecting him from overthrow, (890–894). she also (apparently with malice) gives birth to Zeus' worst enemy Typhon; West 1966, p. 24, sees in the Tiamat story a possible explanation for this "odd little inconsistency".

- Fontenrose, p. 145; Watkins, pp. 448 ff.; Ogden 2013a, pp. 14–15, 75. For a detailed discussion of the myths surrounding the Jebel Aqra and their relationship with the Typhonomachy see Lane Fox, pp. 242–301.

- Fontenrose, pp. 129–138; West 1997, pp. 84–87; Lane Fox, pp. 244–245, 282; Ogden 2013a, pp. 12, 14, 75.

- Fontenrose, pp. 121–125; West 1966, pp. 391–392 line 853; Burkert, p. 20; Penglase, pp. 163–164; Watkins, pp. 444–446; West 1997, p. 304; Lane Fox, pp. 284–285; Ogden 2013a, pp. 12–13, 75, 77–78.

- West 1966, pp. 21–22, 391–392 line 853; Penglase, p. 164 (who calls Tarhunna by his Hurrian name Teshub); Lane Fox, pp. 286–287; Ogden 2013a, pp. 77–78

- Lane Fox, pp. 245, 284, 285–286; Ogden 2013a, p. 13.

- West 1966, pp. 21, 379–380, 381; Burkert, p. 20; Penglase, pp. 156, 159, 163; West 1997, pp. 103–104; Lane Fox, p. 286.

- Fowler 2013, p. 28; Ogden 2013a, p. 78; West 1997, p. 304; West 1966, p. 380; Fontenrose, p. 177 ff.; Hecataeus FGrH 1 F300 (apud Herodotus, 2.144.2).

- Griffiths, pp. 374–375; Pindar, fr. 91 SM apud Porphyry, On Abstinence From Animal Food 3.16 (Taylor, p. 111); Fowler 2013, p. 29; Ogden 2013a, p. 217; Gantz, p. 49; West 1966, p. 380; Fontenrose, p. 75. For the gods' transformation and flight to Egypt see also Nicander, apud Antoninus Liberalis 28, Hyginus, Astronomica 2.28, 2.30; Ovid, Metamorphoses 5.321–331; Apollodorus, 1.6.3.

- Ogden 2013b, p. 23; Griffiths, pp. 374–375; Fontenrose, pp. 75, 177.

- Fowler 2013, p. 28; Herodotus, 2.144.2; cf. 2.156.4.

- Herodotus, 3.5.

- Ogden 2013b, p. 21. Hesiod, Theogony 185, has the Giants being the offspring of Gaia (Earth), born from the blood that fell when Uranus (Sky) was castrated by his Titan son Cronus. Hyginus, Fabulae Preface gives Tartarus as the father of the Giants.

- Apollodorus, 1.6.1–2. Their war with the Olympian gods was known as the Gigantomachy.

- Gantz, p. 453; Hanfmann, The Oxford Classical Dictionary s.v. "Giants"; Frazer, note to 8.29.3 "That the giants have serpents instead of feet" pp. 315–316.

- As noted above, the Giant Enceladus was said to lie buried under Mount Etna. For the Giants Alcyoneus (along with "many giants") under Mount Vesuvius, see Philostratus, On Heroes 8.15–16 (p. 14); Claudian, Rape of Proserpine 3.183–184 (pp. 358–359); for Mimas under the volcanic island of Prochyte (modern Procida), see Silius Italicus, Punica 12.143–151 (pp. 156–159); and for Polybotes under the volcanic island of Nisyros, see Apollodorus, 1.6.2.

- Rose, The Oxford Classical Dictionary s.v. "Typhon, Typhoeus"; Fontenrose, p. 80.

- Hyginus, Fabulae Preface.

- Horace, Odes 3.4.53.

- Manilius, Astronomica 2.874–880 (pp. 150–151).

- Ogden 2013b, p. 33. See for example Nonnus, Dionysiaca 1.176 (I pp. 16–17), 1.220 (I pp. 18–19), 1.244 (I pp. 20–21), 1.263 (I pp. 22–23), 1.291 (I pp. 24–25).

References

- Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes in Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. Vol 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1926.

- Aeschylus (?), Prometheus Bound in Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. Vol 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1926. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Anonymous, Homeric Hymn to Apollo, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Antoninus Liberalis, Celoria, Francis, The Metamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalis: A Translation with Commentary, Psychology Press, 1992. ISBN 9780415068963.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Apollonius Rhodius: the Argonautica, translated by Robert Cooper Seaton, W. Heinemann, 1912. Internet Archive

- Aristophanes, Clouds in The Comedies of Aristophanes, William James Hickie. London. Bohn. 1853?. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Bacchylides, Odes, translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1991. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Burkert, "Oriental and Greek Mythology: The Meeting of Parallels" in Interpretations of Greek Mythology, Edited by Jan Bremmer, Routledge, 2014 (first published 1987). ISBN 978-0-415-74451-5.

- Campbell, David A., Greek Lyric III: Stesichorus, Ibycus, Simonides, and Others, Harvard University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0674995253.

- Claudian, Claudian with an English translation by Maurice Platnauer, Volume II, Loeb Classical Library No. 136. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd.. 1922. ISBN 978-0674991514. Internet Archive.

- Clay, Jenny Strauss, Hesiod's Cosmos, Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-82392-0.

- Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. Online version by Bill Thayer

- Euripides, The Phoenician Women, translated by E. P. Coleridge in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. Volume 2. New York. Random House. 1938.

- Euripides, Iphigenia in Tauris, translated by Robert Potter in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. Volume 2. New York. Random House. 1938. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins, University of California Press, 1959. ISBN 9780520040915.

- Fowler, R. L. (2000), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 1: Text and Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0198147404.

- Fowler, R. L. (2013), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0198147411.

- Frazer, J. G., Pausanias's Description of Greece. Translated with a Commentary by J. G. Frazer. Vol IV. Commentary on Books VI-VIII, Macmillan, 1898. Internet Archive.

- Freeman, Kathleen, Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers: A Complete Translation of the Fragments in Diels, Fragmente Der Vorsokratiker, Harvard University Press, 1983. ISBN 9780674035010.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths, (1955) 1960, §36.1–3

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn, "The Flight of the Gods Before Typhon: An Unrecognized Myth", Hermes, 88, 1960, pp. 374–376. JSTOR

- George M. A. Hanfmann, "Giants" in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, second edition, Hammond, N.G.L. and Howard Hayes Scullard (editors), Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-869117-3.

- Herodotus; Histories, A. D. Godley (translator), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920; ISBN 0674991338. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Horace, The Odes and Carmen Saeculare of Horace. John Conington. trans. London. George Bell and Sons. 1882. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hošek, Radislav, "Echidna" in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) III.1. Artemis Verlag, Zürich and Munich, 1986. ISBN 3760887511.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, The Myths of Hyginus. Edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960.

- Kerényi, Carl, The Gods of the Greeks, Thames and Hudson, London, 1951.

- Kirk, G. S., J. E. Raven, M. Schofield, The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, Cambridge University Press, Dec 29, 1983. ISBN 9780521274555.

- Lane Fox, Robin, Travelling Heroes: In the Epic Age of Homer, Vintage Books, 2010. ISBN 9780679763864.

- Lightfoot, J. L. Hellenistic Collection: Philitas. Alexander of Aetolia. Hermesianax. Euphorion. Parthenius. Edited and translated by J. L. Lightfoot. Loeb Classical Library No. 508. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-674-99636-6. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Lucan, Pharsalia, Sir Edward Ridley. London. Longmans, Green, and Co. 1905. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Lycophron, Alexandra (or Cassandra) in Callimachus and Lycophron with an English translation by A. W. Mair ; Aratus, with an English translation by G. R. Mair, London: W. Heinemann, New York: G. P. Putnam 1921. Internet Archive

- Lyne, R. O. A. M., Ciris: A Poem Attributed to Vergil, Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780521606998.

- Manilius, Astronomica, edited and translated by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library No. 469. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1977. Online version at Harvard University Press

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca; translated by Rouse, W H D, I Books I–XV. Loeb Classical Library No. 344, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1940. Internet Archive

- Ogden, Daniel (2013a), Drakon: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 9780199557325.

- Ogden, Daniel (2013b), Dragons, Serpents, and Slayers in the Classical and early Christian Worlds: A sourcebook, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992509-4.

- Oppian, Halieutica in Oppian, Colluthus, Tryphiodorus, With an English Translation by A. W. Mair, London, W. Heinemann, 1928. Internet Archive

- Ovid, Ovid's Fasti: With an English translation by Sir James George Frazer, London: W. Heinemann LTD; Cambridge, Massachusetts: : Harvard University Press, 1959. Internet Archive.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Brookes More. Boston. Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Penglase, Charles, Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod, Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005 (first published 1994 by Routledge). ISBN 0-203-44391-8. PDF.

- Philostratus, On Heroes, editors Jennifer K. Berenson MacLean, Ellen Bradshaw Aitken, BRILL, 2003, ISBN 9789004127012.

- Pindar, Odes, Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Quintus Smyrnaeus: The Fall of Troy, Translator: A.S. Way; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1913. Internet Archive

- Race, William H., Nemean Odes. Isthmian Odes. Fragments, Edited and translated by William H. Race. Loeb Classical Library 485. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997, revised 2012. ISBN 978-0-674-99534-5. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Rose, Herbert Jennings, "Typhon, Typhoeus" in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, second edition, Hammond, N.G.L. and Howard Hayes Scullard (editors), Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-869117-3.

- Seneca, Tragedies, Volume I: Hercules. Trojan Women. Phoenician Women. Medea. Phaedra. Edited and translated by John G. Fitch. Loeb Classical Library No. 62. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-674-99602-1. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Seneca, Tragedies, Volume II: Oedipus. Agamemnon. Thyestes. Hercules on Oeta. Octavia. Edited and translated by John G. Fitch. Loeb Classical Library No. 78. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-674-99610-6. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Silius Italicus, Punica with an English translation by J. D. Duff, Volume II, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1934. Internet Archive.

- Sophocles, Women of Trachis, Translated by Robert Torrance. Houghton Mifflin. 1966. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Strabo, Geography, translated by Horace Leonard Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. (1924). LacusCurtis, Books 6–14, at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Taylor, Thomas, Select Works of Porphyry: Containing His Four Books on Abstinence from Animal Food, His Treatise on the Homeric Cave of the Nymphs and His Auxiliaries to the Perception of Intelligible Natures, London, T. Rodd, 1823. Internet Archive

- Trypanis, C. A., Gelzer, Thomas; Whitman, Cedric, CALLIMACHUS, MUSAEUS, Aetia, Iambi, Hecale and Other Fragments. Hero and Leander, Harvard University Press, 1975. ISBN 978-0-674-99463-8.

- Tzetzes, Chiliades, editor Gottlieb Kiessling, F.C.G. Vogel, 1826. (English translation, Books II–IV, by Gary Berkowitz. Internet Archive).

- Valerius Flaccus, Gaius, Argonautica, translated by J. H. Mozley, Loeb Classical Library Volume 286. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1928.

- Jean-Pierre Vernant, The Origins of Greek Thought. Cornell University Press, 1982. Google books

- Virgil; Bucolics, Aeneid, and Georgics Of Vergil. J. B. Greenough. Boston. Ginn & Co. 1900. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Calvert Watkins, How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics", Oxford University Press. 1995. ISBN 0-19-508595-7. PDF.

- West, M. L. (1966), Hesiod: Theogony, Oxford University Press.

- West, M. L. (1997), The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815042-3.

External links

Media related to Typhon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Typhon at Wikimedia Commons