Waldorf education

Waldorf education, also known as Steiner education, is based on the educational philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Anthroposophy. Its pedagogy strives to develop pupils' intellectual, artistic, and practical skills in an integrated and holistic manner. The cultivation of pupils' imagination and creativity is a central focus.

Individual teachers and schools have a great deal of autonomy in determining curriculum content, teaching methodology, and governance. Qualitative assessments of student work are integrated into the daily life of the classroom, with quantitative testing playing a minimal role and standardized testing usually limited to what is required to enter post-secondary education.

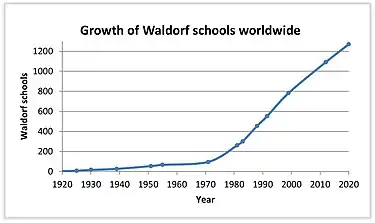

The first Waldorf school opened in 1919[1] in Stuttgart, Germany. A century later, it has become the largest independent school movement in the world,[2] with about 1,200 independent Waldorf schools,[3] 2,000 kindergartens[4] and 646 centers for special education[5] located in 75 countries. Germany is the country with the most Waldorf schools, followed by the United States.[6] There are also a number of Waldorf-based public schools,[7] charter schools and academies, and homeschooling[8] environments.

Some Waldorf schools in English-speaking countries have met opposition due to vaccine hesitancy among the parents of some Waldorf pupils, differences in education standards, and the mystical and antiquated nature of some of Steiner's theories.[9][10][11][12][13]

| Continent | Schools | Kindergartens | Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | 803 | 138 | 37 |

| North America | 202[14] | 176 | 2 |

| Central America | 17 | 18 | 4 |

| South America | 62 | 135 | 7 |

| Asia | 65 | 42 | 15 |

| Oceania | 69 | 50 | 3 |

| Africa | 21 | 21 | 5 |

| Total | 1239 | 580 | 71 |

Origins and history

The first school based upon the ideas of Rudolf Steiner was opened in 1919 in response to a request from Emil Molt, the owner and managing director of the Waldorf-Astoria Cigarette Company in Stuttgart, Germany. This is the source of the name Waldorf, which is now trademarked in some countries when used in connection with the overall method that grew out of this original Waldorf school.[16] Molt's proposed school would educate the children of employees of the factory.[17]:381

Molt was a follower of Anthroposophy, the esoteric spiritual movement based on the notion that an objectively comprehensible spiritual realm exists and can be observed by humans. Emil Molt was also a close confidant of Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophy's founder and spiritual leader.[18] Many of Steiner's ideas influenced the pedagogy of the original Waldorf school and still play a central role in modern Waldorf classrooms (reincarnation,[19] karma,[20][21] the existence of gnomes,[22] eurythmy).[23]

As the co-educational school also served children from outside the factory, it included children from a diverse social spectrum. It was also the first comprehensive school in Germany.[24][25][26][27]

Waldorf education became more widely known in Britain in 1922 through lectures Steiner gave at a conference at Oxford University on educational methods.[28] Two years later, on his final trip to Britain at Torquay in 1924, Steiner delivered a Waldorf teacher training course.[29] The first school in England (Michael Hall) was founded in 1925; the first in the United States (the Rudolf Steiner School in New York City) in 1928. By the 1930s, numerous schools inspired by the original and/or Steiner's pedagogical principles had opened in Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Norway, Austria, Hungary, the United States, and England.[30]

From 1933 to 1945, political interference from the Nazi regime limited and ultimately closed most Waldorf schools in Europe, with the exception of the British, Swiss, and some Dutch schools. The affected schools were reopened after the Second World War,[31][32] though those in Soviet-dominated Eastern Germany were closed again a few years later by the Communist German Democratic Republic government.[33]

In North America, the number of Waldorf schools increased from nine in the United States[34] and one in Canada[35] in 1967 to around 200 in the United States[3][36][37] and over 20 in Canada[38] as of 2014. There are currently 29 Steiner schools in the United Kingdom and 3 in the Republic of Ireland.[39]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Waldorf schools again began to proliferate in Central and Eastern Europe. Most recently, many schools have opened in Asia, especially in China.[40][41] There are currently over 1,000 independent Waldorf schools worldwide.[3]

Developmental approach

The structure of Waldorf education follows a theory of childhood development devised by Rudolf Steiner, utilizing three distinct learning strategies for each of three distinct developmental stages.[17][42][43] These stages each last approximately seven years, as Steiner believed human beings develop in seven-year-long spiritual cycles. He also believed each stage was imbued with a different "sphere" - the Moon (0-7 years old), Mercury (7-14 years old), and Venus (14-21 years old).[44][45][46][47][48] Aside from these spiritual underpinnings, Steiner's seven-year stages are broadly similar to those later described by Jean Piaget.[17]:402[49] In other respects, Steiner's ideas are descended similarly from educational theories developed by Comenius and Pestalozzi.[50] The stated purpose of this approach is to awaken the "physical, behavioral, emotional, cognitive, social, and spiritual" aspects of each individual,[51] fostering creative and inquisitive thought.[51]:28 :39

Where is the book in which the teacher can read about what teaching is? The children themselves are this book. We should not learn to teach out of any book other than the one lying open before us and consisting of the children themselves.

— Rudolf Steiner, Human Values in Education[52]

Early childhood

Waldorf pedagogical theory considers that during the first years of life children learn best by being immersed in an environment they can learn through un-selfconscious imitation of practical activities. The early childhood curriculum therefore centers on experiential education, allowing children to learn by example, and opportunities for imaginative play.[53][54][55][56] The overall goal of the curriculum is to "imbue the child with a sense that the world is good".[57]

Waldorf preschools employ a regular daily routine that includes free play, artistic work (e.g. drawing, painting or modeling), circle time (songs, games, and stories), and practical tasks (e.g. cooking, cleaning, and gardening), with rhythmic variations.[58] Periods of outdoor recess are also usually included.[57]:125 The classroom is intended to resemble a home, with tools and toys usually sourced from simple, natural materials that lend themselves to imaginative play.[59] The use of natural materials has been widely praised as fulfilling children's aesthetic needs, encouraging their imagination, and reinforcing their identification with nature,[59][60][61][62] though one pair of reviewers questioned whether the preference for natural, non-manufactured materials is "a reaction against the dehumanizing aspects of nineteenth-century industrialization" rather than a "reasoned assessment of twenty-first century children's needs".[63]

Pre-school and kindergarten programs generally include seasonal festivals drawn from a variety of traditions, with attention placed on the traditions brought forth from the community.[64] Waldorf schools in the Western Hemisphere have traditionally celebrated Christian festivals,[65] though many North American schools also include Jewish festivals.[66]

Waldorf kindergarten and lower grades generally discourage pupils' use of electronic media such as television and computers.[55] There are a variety of reasons for this: Waldorf educators believe that use of these conflicts with young children's developmental needs,[67] media users may be physically inactive, and media may be seen to contain inappropriate or undesirable content and to hamper the imagination.[68]

Elementary education

Waldorf pedagogues consider that readiness for formal learning depends upon increased independence of character, temperament, habits, and memory, one of the markers of which is the loss of the baby teeth.[17]:389[50][69] Formal instruction in reading, writing, and other academic disciplines are therefore not introduced until students enter the elementary school, when pupils are around seven years of age.[70] Steiner believed that engaging young children in abstract intellectual activity too early would adversely affect their growth and development.[17]:389

Waldorf elementary schools (ages 7–14) emphasize cultivating children's emotional life and imagination. In order that students can connect more deeply with the subject matter, academic instruction is presented through artistic work that includes story-telling, visual arts, drama, movement, vocal and instrumental music, and crafts.[71][72][73] The core curriculum includes language arts, mythology, history, geography, geology, algebra, geometry, mineralogy, biology, astronomy, physics, chemistry, and nutrition.[57] The school day generally begins with a one-and-a-half to two-hour, cognitively oriented academic lesson, or "Main lesson", that focuses on a single theme over the course of about a month's time.[57]:145 This typically begins with introductory activities that may include singing, instrumental music, and recitations of poetry, generally including a verse written by Steiner for the start of a school day.[65]

Elementary school educators' stated task is to present a role model children will naturally want to follow, gaining authority through fostering rapport and "nurturing curiosity, imagination, and creativity".[74][75] The declared goal of this second stage is to "imbue children with a sense that the world is beautiful".[57] There is little reliance on standardized textbooks.[50]

Waldorf elementary education allows for individual variations in the pace of learning, based upon the expectation that a child will grasp a concept or achieve a skill when he or she is ready.[31] Cooperation takes priority over competition.[76] This approach also extends to physical education; competitive team sports are introduced in upper grades.[55]

Each class normally remains together as a cohort throughout their years, developing as a quasi-familial social group whose members know each other quite deeply.[77] In the elementary years, a core teacher teaches the primary academic subjects. A central role of this class teacher is to provide supportive role models both through personal example and through stories drawn from a variety of cultures,[57] educating by exercising creative, loving authority. Class teachers are normally expected to teach a group of children for several years,[78] a practice known as looping. The traditional goal was for the teacher to remain with a class for the eight years of the "lower school" cycle, but in recent years the duration of these cycles has been increasingly treated flexibly. Already in first grade, specialized teachers teach many of the subjects, including music, crafts, movement, and two foreign languages from complementary language families[17] (in English-speaking countries often German and either Spanish or French); these subjects remain central to the curriculum throughout the elementary school years.

While class teachers serve a valuable role as personal mentors, establishing "lasting relationships with pupils",[78] especially in the early years, Ullrich documented problems when the same class teacher continues into the middle school years. Noting that there is a danger of any authority figure limiting students enthusiasm for inquiry and assertion of autonomy, he emphasized the need for teachers to encourage independent thought and explanatory discussion in these years, and cited approvingly a number of schools where the class teacher accompanies the class for six years, after which specialist teachers play a significantly greater role.[57]:222

Four temperaments

Steiner considered children's cognitive, emotional and behavioral development to be interlinked.[79] When students in a Waldorf school are grouped, it is generally not by a singular focus on their academic abilities.[51]:89 Instead Steiner adapted the proto-psychological concept of the classic four temperaments – melancholic, sanguine, phlegmatic and choleric – for pedagogical use in the elementary years.[80] Steiner indicated that teaching should be differentiated to accommodate the different needs that these psychophysical types[81] represent. For example, "cholerics are risk takers, phlegmatics take things calmly, melancholics are sensitive or introverted, and sanguines take things lightly".[51]:18 Today Waldorf teachers may work with the notion of temperaments to differentiate their instruction. Seating arrangements and class activities may be planned taking into account the temperaments of the students[82] but this is often not readily apparent to observers.[83] Steiner also believed that teachers must consider their own temperament and be prepared to work with it positively in the classroom,[84] that temperament is emergent in children,[31] and that most people express a combination of temperaments rather than a pure single type.[80]

Secondary education

In most Waldorf schools, pupils enter secondary education when they are about fourteen years old. Secondary education is provided by specialist teachers for each subject. The education focuses much more strongly on academic subjects, though students normally continue to take courses in art, music, and crafts.[57] The curriculum is structured to foster pupils' intellectual understanding, independent judgment, and ethical ideals such as social responsibility, aiming to meet the developing capacity for abstract thought and conceptual judgment.[53][59]

In the third developmental stage (14 years old and up), children in Waldorf programs are supposed to learn through their own thinking and judgment.[85] Students are asked to understand abstract material and expected to have sufficient foundation and maturity to form conclusions using their own judgment.[17]:391 The intention of the third stage is to "imbue children with a sense that the world is true".[57]

The overarching goals are to provide young people the basis on which to develop into free, morally responsible,[51][86] and integrated individuals,[71][87][88] with the aim of helping young people "go out into the world as free, independent and creative beings".[89] No independent studies have been published as to whether or not Waldorf education achieves this aim.[77]

Educational theory and practice

The philosophical foundation of the Waldorf approach, anthroposophy, underpins its primary pedagogical goals: to provide an education that enables children to become free human beings, and to help children to incarnate their "unfolding spiritual identity", carried from the preceding spiritual existence, as beings of body, soul, and spirit in this lifetime.[90] Educational researcher Martin Ashley suggests that the latter role would be problematic for secular teachers and parents in state schools,[77] and the commitment to a spiritual background both of the child and the education has been problematic for some committed to a secular perspective.[37][77][91]

While anthroposophy underpins the curriculum design, pedagogical approach, and organizational structure, it is explicitly not taught within the school curriculum and studies have shown that Waldorf pupils have little awareness of it.[51]:6 Tensions may arise within the Waldorf community between the commitment to Steiner's original intentions, which has sometimes acted as a valuable anchor against following educational fads, and openness to new directions in education, such as the incorporation of new technologies or modern methods of accountability and assessment.[77]

Waldorf schools frequently have striking architecture, employing walls meeting at varied angles (not only perpendicularly) to achieve a more fluid, less boxed-in feeling to the space. The walls are often painted in subtle colors, often with a lazure technique, and include textured surfaces.[92]

Assessment

The schools primarily assess students through reports on individual academic progress and personal development. The emphasis is on characterization through qualitative description. Pupils' progress is primarily evaluated through portfolio work in academic blocks and discussion of pupils in teacher conferences. Standardized tests are rare, with the exception of examinations necessary for college entry taken during the secondary school years.[57]:150,186 Letter grades are generally not given until students enter high school at 14–15 years,[93] as the educational emphasis is on children's holistic development, not solely their academic progress.[57] Pupils are not normally asked to repeat years of elementary or secondary education. It is noted that Waldorf education is not a matter of "assessment-driven instruction or vice-versa" and there is no anxiety-producing experience on the part of the learner of suddenly being tested.[94]

Curriculum

Though Waldorf schools are autonomous institutions not required to follow a prescribed curriculum (beyond those required by local governments) there are widely agreed upon guidelines for the Waldorf curriculum, supported by the schools' common principles.[67] The schools offer a wide curriculum "governed by close observation and recording of what content motivates children at different ages" and including within it, for example, the English, Welsh and Northern Irish National Curriculum.[95]

The main academic subjects are introduced through up to two-hour morning lesson blocks that last for several weeks.[51]:18 These lesson blocks are horizontally integrated at each grade level in that the topic of the block will be infused into many of the activities of the classroom and vertically integrated in that each subject will be revisited over the course of the education with increasing complexity as students develop their skills, reasoning capacities and individual sense of self. This has been described as a spiral curriculum.[96]

Many subjects and skills not considered core parts of mainstream schools, such as art, music, gardening, and mythology, are central to Waldorf education.[97] Students learn a variety of fine and practical arts. Elementary students paint, draw, sculpt, knit, weave, and crochet.[98] Older students build on these experiences and learn new skills such as pattern-making and sewing, wood and stone carving, metal work, book-binding,[99] and doll or puppet making. Fine art instruction includes form drawing, sketching, sculpting, perspective drawing and other techniques.

Music instruction begins with singing in early childhood and choral instruction remains an important component through the end of high school. Pupils usually learn to play pentatonic flutes, recorders and/or lyres in the early elementary grades. Around age 9, diatonic recorders and orchestral instruments are introduced.[100]

Certain subjects are largely unique to the Waldorf schools. Foremost among these is eurythmy, a movement art usually accompanying spoken texts or music which includes elements of drama and dance and is designed to provide individuals and classes with a "sense of integration and harmony".[76] Although found in other educational contexts, cooking,[101] farming,[102] and environmental and outdoor education[103] have long been incorporated into the Waldorf curriculum. Other differences include: non-competitive games and free play in the younger years as opposed to athletics instruction; instruction in two foreign languages from the beginning of elementary school; and an experiential-phenomenological approach to science[104] whereby students observe and depict scientific concepts in their own words and drawings[105] rather than encountering the ideas first through a textbook.

The Waldorf curriculum aims to incorporate multiple intelligences.[106]

Science

The scientific methodology of modern Waldorf schools utilizes a so-called "phenomenological approach" to science education employing a methodology of inquiry-based learning aiming to "strengthen the interest and ability to observe" in pupils.[107]:111 The main aim is to cultivate a sense of "wholeness" in regard to the human's place in nature.[107]:113 Several empirical studies have noted how this method appears effective and even exemplary when evaluated against age-matched peers using the internationally recognized PISA test of 15-year-old students in mathematics and science.[51][108][109]

Other experts have called into question the quality of this phenomenological approach if it fails to educate Waldorf students on basic tenets of scientific fact.[110] One study conducted by California State University at Sacramento researchers outlined numerous theories and ideas prevalent throughout Waldorf curricula that were patently pseudoscientific and steeped in magical thinking. These included the idea that animals evolved from humans, that human spirits are physically incarnated into "soul qualities that manifested themselves into various animal forms", that the current geological formations on Earth have evolved through so-called "Lemurian" and "Atlantiean" epochs, and that the four kingdoms of nature are "mineral, plant, animal, and man". All of these are directly contradicted by mainstream scientific knowledge and have no basis in any form of conventional scientific study. Contradictory notions found in Waldorf textbooks are distinct from factual inaccuracies occasionally found in modern public school textbooks, as the inaccuracies in the latter are of a specific and minute nature that results from the progress of science. The inaccuracies present in Waldorf textbooks, however, are the result of a mode of thinking that has no valid basis in reason or logic.[111] This unscientific foundation has been blamed for the scarcity of systematic empirical research on Waldorf education as academic researchers hesitate in getting involved in studies of Waldorf schools lest it hamper their future career.[112]

One study of the science curriculum compared a group of American Waldorf school students to American public school students on three different test variables.[107] Two tests measured verbal and non-verbal logical reasoning and the third was an international TIMSS test. The TIMSS test covered scientific understanding of magnetism. The researchers found that Waldorf school students scored higher than both the public school students and the national average on the TIMSS test while scoring the same as the public school students on the logical reasoning tests.[107] However, when the logical reasoning tests measured students' understanding of part-to-whole relations, the Waldorf students also outperformed the public school students.[107] The authors of the study noted the Waldorf students' enthusiasm for science, but viewed the science curriculum as "somewhat old-fashioned and out of date, as well as including some doubtful scientific material".[107] Educational researchers Phillip and Glenys Woods, who reviewed this study, criticized the authors' implication of an "unresolved conflict": that it is possible for supposedly inaccurate science to lead to demonstrably better scientific understanding.[113]

In 2008, Stockholm University terminated its Waldorf teacher training courses. In a statement the university said "the courses did not encompass sufficient subject theory and a large part of the subject theory that is included is not founded on any scientific base". The dean, Stefan Nordlund, stated "the syllabus contains literature which conveys scientific inaccuracies that are worse than woolly; they are downright dangerous".[114]

Information technology

Because they view human interaction as the essential basis for younger children's learning and growth,[77]:212 Waldorf schools view computer technology as being first useful to children in the early teen years, after they have mastered "fundamental, time-honoured ways of discovering information and learning, such as practical experiments and books".[115]

In the United Kingdom, Waldorf schools are granted an exemption by the Department for Education (DfE) from the requirement to teach ICT as part of Foundation Stage education (ages 3–5). Education researchers John Siraj-Blatchford and David Whitebread praised the [DfE] for making this exemption, highlighting Waldorf education's emphasis on simplicity of resources and the way the education cultivates the imagination.[63]

Waldorf schools have been popular with some parents working in the technology sector in the United States, including those from some of the most advanced technology firms.[116][117][118][119] A number of technologically oriented parents from one school expressed their conviction that younger students do not need the exposure to computers and technology, but benefit from creative aspects of the education; one Google executive was quoted as saying "I fundamentally reject the notion you need technology aids in grammar school."[120]

Spirituality

Waldorf education aims to educate children about a wide range of religious traditions without favoring any one of these.[76] One of Steiner's primary aims was to establish a spiritual yet nondenominational setting for children from all backgrounds[71]:79[92][121] that recognized the value of role models drawn from a wide range of literary and historical traditions in developing children's fantasy and moral imaginations.[50]:78 Indeed, for Steiner, education was an activity which fosters the human being's connection to the divine and is thus inherently religious.[122]:1422,1430

Waldorf schools were historically "Christian based and theistically oriented",[73] as they expand into different cultural settings they are adapting to "a truly pluralistic spirituality".[51]:146 Waldorf theories and practices are often modified from their European and Christian roots to meet the historical and cultural traditions of the local community.[123] Examples of such adaptation include the Waldorf schools in Israel and Japan, which celebrate festivals drawn from these cultures, and classes in the Milwaukee Urban Waldorf school, which have adopted African American and Native American traditions.[76] Such festivals, as well as assemblies generally, which play an important role in Waldorf schools, generally center on classes presenting their work.

Religion classes are usually absent from United States Waldorf schools, [124] are a mandatory offering in some German federal states, whereby in Waldorf schools each religious denomination provides its own teachers for the classes, and a non-denominational religion class is also offered. In the United Kingdom, public Waldorf schools are not categorized as "Faith schools".[125]

Tom Stehlik places Waldorf education in a humanistic tradition, and contrasts its philosophically grounded approach to "value-neutral" secular state schooling systems.[84]

Teacher education

Waldorf teacher education programs offer courses in child development, the methodology of Waldorf teaching, academic subjects appropriate to the future teachers' chosen specialty, and the study of pedagogical texts and other works by Steiner.[2][126][127] For early childhood and elementary school teachers, the training includes considerable artistic work in storytelling, movement, painting, music, and handwork.[128]

Waldorf teacher education includes social–emotional development as "an integral and central element", which is unusual for teacher trainings.[129] A 2010 study found that students in advanced years of Waldorf teacher training courses scored significantly higher than students in non-Waldorf teacher trainings on three measures of empathy: perspective taking, empathic concern and fantasy.[129]

Governance

Independent schools

One of Waldorf education's central premises is that all educational and cultural institutions should be self-governing and should grant teachers a high degree of creative autonomy within the school;[130]:143[73] this is based upon the conviction that a holistic approach to education aiming at the development of free individuals can only be successful when based on a school form that expresses these same principles.[131] Most Waldorf schools are not directed by a principal or head teacher, but rather by a number of groups, including:

- The college of teachers, who decide on pedagogical issues, normally on the basis of consensus. This group is usually open to full-time teachers who have been with the school for a prescribed period of time. Each school is accordingly unique in its approach, as it may act solely on the basis of the decisions of the college of teachers to set policy or other actions pertaining to the school and its students.[65]

- The board of trustees, who decide on governance issues, especially those relating to school finances and legal issues, including formulating strategic plans and central policies.[132]

Parents are encouraged to take an active part in non-curricular aspects of school life.[76] Waldorf schools have been found to create effective adult learning communities.[133]

There are coordinating bodies for Waldorf education at both the national (e.g. the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America and the Steiner Waldorf Schools Fellowship in the UK and Ireland) and international level (e.g. International Association for Waldorf Education and The European Council for Steiner Waldorf Education (ECSWE)). These organizations certify the use of the registered names "Waldorf" and "Steiner school" and offer accreditations, often in conjunction with regional independent school associations.[134]

United States

The first US Waldorf-inspired public school, the Yuba River Charter School in California, opened in 1994. The Waldorf public school movement is currently expanding rapidly; while in 2010, there were twelve Waldorf-inspired public schools in the United States,[135] by 2018 there were 53 such schools.[36]

Most Waldorf-inspired schools in the United States are elementary schools established as either magnet or charter schools. The first Waldorf-inspired high school was launched in 2008 with assistance from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.[135] While these schools follow a similar developmental approach as the independent schools, Waldorf-inspired schools must demonstrate achievement on standardized tests in order to continue receiving public funding. Studies of standardized test scores suggest that students at Waldorf-inspired schools tend to score below their peers in the earliest grades and catch up[135] or surpass[126] their peers by middle school. One study found that students at Waldorf-inspired schools watch less television and spend more time engaging in creative activities or spending time with friends.[135] Public Waldorf schools' need to demonstrate achievement through standardized test scores has encouraged increased use of textbooks and expanded instructional time for academic subjects.[135]

A legal challenge alleging that California school districts' Waldorf-inspired schools violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments of the United States Constitution and Article IX of the California Constitution was dismissed on its merits in 2005[136] and on appeal in 2007[137] and 2012.

United Kingdom

The first state-funded Steiner-Waldorf school in the United Kingdom, the Steiner Academy Hereford, opened in 2008. Since then, Steiner academies have opened in Frome, Exeter and Bristol as part of the government-funded free schools programme.

In December 2018, Ofsted judged the Steiner Academy Exeter as inadequate and ordered it to be transferred to a multi-academy trust; it was temporarily closed in October 2018 because of concerns. The concerns included significant lapses in safeguarding, and mistreating children with special educational needs and disabilities, and misspending the funding designated for them.[138] Another incident was that in July 2018, two 6-year-old children were found by police having walked out of the school unnoticed, and their parents were not informed until the end of the day.[139] Subsequently, the Steiner Academies in Bristol and Frome have also been judged inadequate by Ofsted, because of concerns over safeguarding and bullying, and a number of private Steiner schools have also been judged inadequate.[140] Overall, several Waldorf schools in the UK have closed in the last decade due to their administrations' failure to adhere to state-mandated standards of education (e.g. required levels of literacy, safety standards for child welfare, and mistreatment of special needs children).[141][142][143]

In November 2012, BBC News broadcast an item about accusations that the establishment of a state-funded Waldorf School in Frome was a misguided use of public money. The broadcast reported that concerns were being raised about Rudolf Steiner's beliefs, stating he "believed in reincarnation and said it was related to race, with black (schwarz) people being the least spiritually developed, and white (weiß) people the most".[144] In 2007 the European Council for Steiner Waldorf Education (ECSWE) issued a statement, "Waldorf schools against discrimination", which said in part, "Waldorf schools do not select, stratify or discriminate amongst their pupils, but consider all human beings to be free and equal in dignity and rights, independent of ethnicity, national or social origin, gender, language, religion, and political or other convictions. Anthroposophy, upon which Waldorf education is founded, stands firmly against all forms of racism and nationalism."[145]

The British Humanist Association criticised a reference book used to train teachers in Steiner academies for suggesting that the heart is sensitive to emotions and promoting homeopathy, while claiming that Darwinism is "rooted in reductionist thinking and Victorian ethics". Edzard Ernst, emeritus professor of complementary medicine, said that Waldorf schools "seem to have an anti-science agenda". A United Kingdom Department for Education spokeswoman said "no state school is allowed to teach homeopathy as scientific fact" and that free schools "must demonstrate that they will provide a broad and balanced curriculum".[146]

Australia, New Zealand, and Canada

Australia has "Steiner streams" incorporated into a small number of existing government schools in some states; in addition, independent Steiner-Waldorf schools receive partial government funding. The majority of Steiner-Waldorf schools in New Zealand are Integrated Private Schools under The Private Schools Integration Act 1975, thus receiving full state funding. In the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Quebec and Alberta, all private schools receive partial state funding.[147]

Russia

The first Steiner school in Russia was established in 1992 in Moscow.[148] That school is now an award-winning government-funded school with over 650 students offering classes for kindergarten and years 1 to 11 (the Russian education system is an eleven year system). There are 18 Waldorf schools in Russia and 30 kindergartens. Some are government funded (with no fees) and some are privately funded (with fees for students). As well as five Waldorf schools in Moscow, there are also Waldorf schools in Saint Petersburg, Irkutsk, Jaroslawl, Kaluga, Samara, Zhukovskiy, Smolensk, Tomsk, Ufa, Vladimir, Voronezh, and Zelenograd. The Association of Russian Waldorf Schools was founded in 1995 and now has 21 members.[148]

Homeschooling

Waldorf-inspired home schools typically obtain their program information through informal parent groups, online, or by purchasing a curriculum. Waldorf homeschooling groups are not affiliated with the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America (AWSNA), which represents independent schools and it is unknown how many home schools use a Waldorf-inspired curriculum.

Educationalist Sandra Chistolini suggests that parents offer their children Waldorf-inspired homeschooling because "the frustration and boredom some children feel in school are eliminated and replaced with constant attention to the needs of childhood [and] connections between content and the real world".[149]

Social engagement

Steiner's belief that all people are imbued with a spiritual core has fueled Waldorf schools' social mission.[150] The schools have always been coeducational and open to children of all social classes. They were designed from the beginning to be comprehensive, 12-year schools under the direction of their own teachers, rather than the state or other external authorities,[151] all radical principles when Steiner first articulated them.[152]

Social renewal and transformation remain primary goals for Waldorf schools,[153] which seek to cultivate pupils' sense of social responsibility.[59][154][155][156] Studies suggest that this is successful;[50]:190[51]:4 Waldorf pupils have been found to be more interested in and engaged with social and moral questions and to have more positive attitudes than students from mainstream schools,[157] demonstrating activism and self-confidence and feeling empowered to forge their own futures.[158]

Waldorf schools build close learning communities, founded on the shared values of its members,[51]:17 in ways that can lead to transformative learning experiences that allow all participants, including parents, to become more aware of their own individual path,[51]:5,17,32,40[84]:238 but which at times also risk becoming exclusive.[50]:167, 207 Reports from small-scale studies suggest that there are lower levels of harassment and bullying in Waldorf schools[51]:29 and that European Waldorf students have much lower rates of xenophobia and gender stereotypes than students in any other type of schools.[159] Betty Reardon, a professor and peace researcher, gives Waldorf schools as an example of schools that follow a philosophy based on peace and tolerance.[160]

Many private Waldorf schools experience a tension between these social goals and the way tuition fees act as a barrier to access to the education by less well-off families. Schools have attempted to improve access for a wider range of income groups by charging lower fees than comparable independent schools, by offering a sliding scale of fees, and/or by seeking state support.[77]

Intercultural links in socially polarized communities

Waldorf schools have linked polarized communities in a variety of settings.

- Under the apartheid regime in South Africa, the Waldorf school was one of the few schools in which children of all apartheid racial classifications attended the same classes, despite the ensuing loss of state aid. A Waldorf training college in Cape Town, the Novalis Institute, was referenced during UNESCO's Year of Tolerance for being an organization that was working towards reconciliation in South Africa.[160][161]

- The first Waldorf school in West Africa was founded in Sierra Leone to educate boys and girls orphaned by the country's civil war.[162] The school building is a passive solar building built by the local community, including the students.[163]

- In Israel, the Harduf Kibbutz Waldorf school includes both Jewish and Arab faculty and students and has extensive contact with the surrounding Arab communities.[164] It also runs an Arab-language Waldorf teacher training.[165] A joint Arab-Jewish Waldorf kindergarten, Ein Bustan, was founded in Hilf (near Haifa) in 2005[166][167] while an Arabic language multi-cultural Druze/Christian/Muslim Waldorf school has operated in Shefa-'Amr since 2003.[168] In Lod, a teacher training program brings together Israeli Arabs and Jews on an equal basis, with the goals of improving Arab education in Israel and offering new career paths to Arab women.[169]

- In Brazil, a Waldorf teacher, Ute Craemer, founded Associação Comunitária Monte Azul, a community service organization providing childcare, vocational training and work, social services including health care, and Waldorf education to more than 1,000 residents of poverty-stricken areas (Favelas) of São Paulo.

- In Nepal, the Tashi Waldorf School in the outskirts of Kathmandu teaches mainly disadvantaged children from a wide variety of cultural backgrounds.[170] It was founded in 1999 and is run by Nepalese staff. In addition, in the southwest Kathmandu Valley a foundation provides underprivileged, disabled and poor adults with work on a biodynamic farm and provides a Waldorf school for their children.[171]

- The T.E. Mathews Community School in Yuba County, California, serves high-risk juvenile offenders, many of whom have learning disabilities. The school switched to Waldorf methods in the 1990s. A 1999 study of the school found that students had "improved attitudes toward learning, better social interaction and excellent academic progress".[172][173] This study identified the integration of the arts "into every curriculum unit and almost every classroom activity" as the most effective tool to help students overcome patterns of failure. The study also found significant improvements in reading and math scores, student participation, focus, openness and enthusiasm, as well as emotional stability, civility of interaction and tenacity.[173]

Waldorf education also has links with UNESCO. In 2008, 24 Waldorf schools in 15 countries were members of the UNESCO Associated Schools Project Network.[174] The Friends of Waldorf Education is an organization whose purpose is to support, finance and advise the Waldorf movement worldwide, particularly in disadvantaged settings.

Reception

Evaluations of students' progress

Although studies about Waldorf education tend to be small-scale and vary in national context, a recent independent comprehensive review of the literature concluded there is evidence that Waldorf education encourages academic achievement as well as "creative, social and other capabilities important to the holistic growth of a person".[51]:39[77]

In comparison to state school pupils, European Waldorf students are significantly more enthusiastic about learning, report having more fun and being less bored in school, view their school environments as pleasant and supportive places where they are able to discover their personal academic strengths,[108] and have more positive views of the future.[175] Twice as many European Waldorf students as state school pupils report having good relationships with teachers; they also report significantly fewer ailments such as headaches, stomach aches, and disrupted sleep.[108]

A 2007 German study found that an above-average number of Waldorf students become teachers, doctors, engineers, scholars of the humanities, and scientists.[176] Studies of Waldorf students' artistic capacities found that they averaged higher scores on the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking Ability,[177] drew more accurate, detailed, and imaginative drawings,[178] and were able to develop richer images than comparison groups.[175]

Some observers have noted that Waldorf educators tend to be more concerned to address the needs of weaker students who need support than they are to meet the needs of talented students who could benefit from advanced work.[179]

Educational scholars

Professor of educational psychology Clifford Mayes said "Waldorf students learn in sequences and paces that are developmentally appropriate, aesthetically stimulating, emotionally supportive, and ecologically sensitive."[180] Professors of education Timothy Leonard and Peter Willis stated that Waldorf education "cultivates the imagination of the young to provide them a firm emotional foundation upon which to build a sound intellectual life".[181]

Professor of education Bruce Uhrmacher considers Steiner's view on education worthy of investigation for those seeking to improve public schooling, saying the approach serves as a reminder that "holistic education is rooted in a cosmology that posits a fundamental unity to the universe and as such ought to take into account interconnections among the purpose of schooling, the nature of the growing child, and the relationships between the human being and the universe at large", and that a curriculum need not be technocratic, but may equally well be arts-based.[17]:382, 401

Thomas Nielsen, assistant professor at the University of Canberra's education department, said that imaginative teaching approaches used in Waldorf education (drama, exploration, storytelling, routine, arts, discussion and empathy) are effective stimulators of spiritual-aesthetic, intellectual and physical development, expanding "the concept of holistic and imaginative education" and recommends these to mainstream educators.[71][182]

Andreas Schleicher, international coordinator of the PISA studies, commented on what he saw as the "high degree of congruence between what the world demands of people, and what Waldorf schools develop in their pupils", placing a high value on creatively and productively applying knowledge to new realms. This enables "deep learning" that goes beyond studying for the next test.[176] Deborah Meier, principal of Mission Hill School and MacArthur grant recipient, while having some "quibbles" about the Waldorf schools, stated: "The adults I know who have come out of Waldorf schools are extraordinary people. That education leaves a strong mark of thoroughness, carefulness, and thoughtfulness."[183]

Robert Peterkin, director of the Urban Superintendents Program at Harvard's Graduate School of Education and former Superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools during a period when Milwaukee funded a public Waldorf school, considers Waldorf education a "healing education" whose underlying principles are appropriate for educating all children.[184]

Waldorf education has also been studied as an example of educational neuroscience ideas in practice.[185]

Germany

In 2000, educational scholar Heiner Ullrich wrote that intensive study of Steiner's pedagogy had been in progress in educational circles in Germany since about 1990 and that positions were "highly controversial: they range from enthusiastic support to destructive criticism".[50] In 2008, the same scholar wrote that Waldorf schools have "not stirred comparable discussion or controversy... those interested in the Waldorf School today... generally tend to view this school form first and foremost as a representative of internationally recognized models of applied classic reform pedagogy"[57]:140–141 and that critics tend to focus on what they see as Steiner's "occult neo-mythology of education" and to fear the risks of indoctrination in a worldview school, but lose an "unprejudiced view of the varied practice of the Steiner schools".[50] Ullrich himself considers that the schools successfully foster dedication, openness, and a love for other human beings, for nature, and for the inanimate world.[57]:179

Professor of Comparative Education Hermann Röhrs describes Waldorf education as embodying original pedagogical ideas and presenting exemplary organizational capabilities.[186]

Relationship with mainstream education

A UK Department for Education and Skills report suggested that Waldorf and state schools could learn from each other's strengths: in particular, that state schools could benefit from Waldorf education's early introduction and approach to modern foreign languages; combination of block (class) and subject teaching for younger children; development of speaking and listening through an emphasis on oral work; good pacing of lessons through an emphasis on rhythm; emphasis on child development guiding the curriculum and examinations; approach to art and creativity; attention given to teachers’ reflective activity and heightened awareness (in collective child study for example); and collegial structure of leadership and management, including collegial study. Aspects of mainstream practice which could inform good practice in Waldorf schools included: management skills and ways of improving organizational and administrative efficiency; classroom management; work with secondary-school age children; and assessment and record keeping.[51]

American state and private schools are drawing on Waldorf education – "less in whole than in part" – in expanding numbers.[187] Professor of Education Elliot Eisner sees Waldorf education exemplifying embodied learning and fostering a more balanced educational approach than American public schools achieve.[188] Ernest Boyer, former president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching commended the significant role the arts play throughout Waldorf education as a model for other schools to follow.[189] Waldorf schools have been described as establishing "genuine community" and contrasted to mainstream schools, which have been described as "residential areas partitioned by bureaucratic authorities for educational purposes".[190]

Many elements of Waldorf pedagogy have been used in all Finnish schools for many years.[176]

Ashley described seven principal ways Waldorf education differed from mainstream approaches: its method of working from the whole to the parts, its attentiveness to child development, its goal of freedom, the deep relationships of teachers to students, the emphasis on experiencing oral traditions, the role of ritual and routine (e.g. welcoming students with a handshake, the use of opening and closing verses, and yearly festivals), the role arts and creativity play, and the Goetheanistic approach to science.[77]

Vaccine exemption

In states where nonmedical vaccine exemption is legal, 2015 reports showed Waldorf schools as having a high rate of vaccine exemption within their student populations, however, recent research has shown that in US state schools, child immunization rates often fall below the 95-percent threshold that the Centers for Disease Control say is necessary to provide “herd immunity” for a community.[191][192][193][194][195][196] A 2010 report by the UK Government said that Steiner schools should be considered "high risk populations" and "unvaccinated communities" with respect to children's risks of catching measles and contributing to outbreaks.[197] On 19 November 2018, the BBC reported there was an outbreak of chickenpox affecting 36 students at the Asheville Waldorf School located in North Carolina.[198] Out of 152 students at the school, 110 had not received the Varicella vaccine that protects against chickenpox.[198] The United States Advisory Committee on Immunization, the Centers for Disease Control, and the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services all recommend that all healthy children 12 months of age and older get vaccinated against Varicella.[199][200][201] The Guardian reported that several Waldorf schools in California had some of the lowest vaccination rates among kindergarten pupils in the 2017–18 school year, with only 7% of pupils having been vaccinated in one school.[202] In the same article, however, The Guardian also reported that, in a 2019 statement, the International Center for Anthroposophic Medicine and the International Federation of Anthroposophic Medical Associations stressed that anthroposophic medicine, the form of medicine Steiner founded, “fully appreciates the contributions of vaccines to global health and firmly supports vaccinations as an important measure to prevent life threatening diseases".[203]

Rudolf Steiner founded the first Waldorf school several years before vaccinations for tetanus, diphtheria, and whooping cough were invented.[204][205] After such vaccinations became widespread in Europe, Steiner opposed their use in several contexts, writing that vaccination could "impede spiritual development" and lead to a loss of "any urge for a spiritual life". Steiner also thought that these effects would carry over into subsequent reincarnations of the vaccinated person.[206]

The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America released the following in a statement in 2019:[207]

The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America wishes to state unequivocally that our educational objectives do not include avoidance of, or resistance to, childhood immunization. The health, safety, and wellbeing of children are our forefront concerns.

- All members of our association are schools or institutions that are free to make independent school policy decisions in accordance with AWSNA's membership and accreditation criteria. Our membership and accreditation criteria require schools to be compliant with national, state, provincial, and local laws. While policy decisions regarding immunizations may vary from school to school, such decisions are made in accordance with legal requirements set by local, state, provincial or federal government.

- The Association encourages parents to consider their civic responsibility in regards to the decision of whether or not to immunize against any communicable disease, but ultimately, the decision to immunize or not is one made by parents in consultation with their family physician.

Race

The Association of Waldorf Schools of North America (AWSNA) and European Council for Steiner Waldorf Education have put out statements stating that "racist or discriminatory tendencies are not tolerated in Waldorf schools or Waldorf teacher training institutes. The Waldorf school movement explicitly rejects any attempt to misappropriate Waldorf pedagogy or Rudolf Steiner's work for racist or nationalistic purposes."[208] Similar statements were put out by the Waldorf school association in Britain ("Our schools do not tolerate racism. Racist views do not accord with Steiner’s longer term vision of a society in which such distinctions would be entirely irrelevant & modern Steiner Waldorf schools deplore all forms of intolerance, aiming to educate in a spirit of respect & to encourage open-hearted regard for others among the children they educate")[209] and Germany.[210]

These statements are the necessary response to Rudolf Steiner's contradictory beliefs about race: he emphasized the core spiritual unity of all the world's peoples, sharply criticized racial prejudice, and articulated beliefs that the individual nature of any person stands higher than any racial, ethnic, national or religious affiliation,[211][212][213] yet he asserted a hierarchy of races, with the white race at the top, and associated intelligence with having blonde hair and blue eyes.[214][215]

In 2019 a school in Christchurch, New Zealand began considering removing Rudolf Steiner from the name of the school "so that the our best ideals are not burdened by historical, philosophical untruths."[216] In 2014, after an investigation by the NZ Ministry of Education, a small school on the Kapiti Coast of New Zealand was cleared of teaching racist theories. An independent investigation concluded that while there were no racist elements in the curriculum, the school needed to make changes in the "areas of governance, management and teaching to ensure parents' complaints were dealt with appropriately in the future...[and that]...the school must continue regular communication with the school community regarding the ongoing work being undertaken to address the issues raised and noted that the board has proactively sought support to do this."[217]

Racist attitudes and behaviour have been reported in particular Waldorf schools, and some teachers have reportedly expressed Steiner's view that individuals reincarnate through various races, however, Kevin Avison, senior advisor for the Steiner Waldorf Schools Fellowship in the UK and Ireland, calls the claim of belief in reincarnation through the races “a complete and utter misunderstanding” of Steiner’s teachings.[215]

References

- Edmunds, Francis (2004). An Introduction to Steiner Education: The Waldorf School. Forest Row: Sophia Books. p. 86. ISBN 9781855841727.

- Zdrazil, Tomas (2018). "Theorie-Praxis Verhältnis in der Waldorfpädagogik". In Kern, Holger; Zdrazil, Tomas; Götte, Wenzel Michael (eds.). Lehrerbildung in der Waldorfschule. Weinheim, DE: Juventa. p. 34. ISBN 9783779938293.

- "Statistics for Waldorf schools worldwide" (PDF).

- [https://ps.goetheanum.org/paedagogik/kindergaerten/ Kindergartens>

- "Website der Freunde der Erziehungskunst Rudolf Steiners e.V." www.freunde-waldorf.de.

- Paull, John & Hennig, Benjamin (2020) Rudolf Steiner Education and Waldorf Schools: Centenary World Maps of the Global Diffusion of "The School of the Future" Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 6(1): 24–33.

- J. Vasagard, "A different class: the expansion of Steiner schools", Guardian 25 May 2012

- M. L. Stevens, "The Normalisation of Homeschooling in the USA", Evaluation & Research in Education Volume 17, Issue 2–3, 2003, pp. 90–100

- "Vaccine deniers: inside the dumb, dangerous new fad". The Verge. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Morgan, Richard E. (1973). "The Establishment Clause and Sectarian Schools: A Final Installment?". The Supreme Court Review. 1973: 57–97. doi:10.1086/scr.1973.3108801. JSTOR 3108801. S2CID 147590904.

- Cook, Chris (4 August 2014). "Why are Steiner schools so controversial?". BBC News.

- "Steiner schools have some questionable lessons for today's children". The Independent. The Independent. 17 May 2019.

- Chertoff, Emily (30 November 2012). "Is This Grade School a 'Cult'? (And Do Parents Care?)". The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- This figure includes 155 private and 47 US public and charter schools. Alliance for Public Waldorf Education list of schools

- Data drawn from Helmut Zander, Anthroposophie in Deutschland, 2 volumes, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht Verlag, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 9783525554524; Dirk Randall, "Empirische Forschung und Waldorfpädogogik", in H. Paschen (ed.) Erziehungswissenschaftliche Zugänge zur Waldorfpädagogik, 2010 Berlin: Springer 978-3-531-17397-9; "Introduction", Deeper insights in education: the Waldorf approach, Rudolf Steiner Press (December 1983) 978-0880100670. p. vii; L. M. Klasse, Die Waldorfschule und die Grundlagen der Waldorfpädagogik Rudolf Steiners, GRIN Verlag, 2007; Ogletree E J "The Waldorf Schools: An International School System", Headmaster U.S.A., pp8-10 Dec 1979; Heiner Ullrich, Rudolf Steiner, Translated by Janet Duke and Daniel Balestrini, Continuum Library of Educational Thought, v. 11, 2008 ISBN 9780826484192.

- "Waldorf Education Trademarks - Association of Waldorf Schools of North America". waldorfeducation.org.

- Uhrmacher, P. Bruce (Winter 1995). "Uncommon Schooling: A Historical Look at Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophy, and Waldorf Education". Curriculum Inquiry. 25 (4): 381–406. doi:10.2307/1180016. JSTOR 1180016.

- Paull, John. "'From Waldorf Tobacco to Waldorf Education' Emil Molt meets Rudolf Steiner". Anthroposophical Society in Australia. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Lewis, Andy (19 March 2013). "Bill Roache, Karma, Reincarnation and Steiner Schools". The Quackometer Blog. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Cook, Chris (4 August 2014). "Why are Steiner schools so controversial?". BBC News. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- "Second Year". Bay Area Center for Waldorf Teacher Training. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- Berlatsky, Noah (1 April 2013). "My Waldorf-Student Son Believes in Gnomes—and That's Fine With Me". The Atlantic. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- Goldshmidt, Gilad (14 February 2017). "Waldorf Education as Spiritual Education". Religion & Education. 44 (3): 346–363. doi:10.1080/15507394.2017.1294400. S2CID 151518278.

- Johannes Hemleben, Rudolf Steiner: A documentary biography, Henry Goulden Ltd, ISBN 0-904822-02-8, pp. 121–126 (German edition Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag ISBN 3-499-50079-5).

- Heiner Ullrich (2002). Inge Hansen-Schaberg, Bruno Schonig (ed.). Basiswissen Pädagogik. Reformpädagogische Schulkonzepte Band 6: Waldorf-Pädagogik. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag Hohengehren. ISBN 978-3-89676503-1.

- Barnes, Henry (1980). "An Introduction to Waldorf Education". Teachers College Record. 81 (3): 323–336.

- Reinsmith, William A. (31 March 1990). "The Whole in Every Part: Steiner and Waldorf Schooling". The Educational Forum. 54 (1): 79–91. doi:10.1080/00131728909335521.

- Paull, John (2011) Rudolf Steiner and the Oxford Conference: The Birth of Waldorf Education in Britain. European Journal of Educational Studies, 3(1): 53–66.

- Paull, John (2018) Torquay: In the Footsteps of Rudolf Steiner, Journal of Biodynamics Tasmania. 125 (Mar): 26–31.

- Friends of Waldorf education, Waldorf schools' Expansion

- Uhrmacher, P. Bruce (1995). "Uncommon Schooling: A Historical Look at Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophy, and Waldorf Education". Curriculum Inquiry. 25 (4): 381–406. doi:10.2307/1180016. JSTOR 1180016.

- A few schools elsewhere in Europe, e.g. in Norway, survived by going underground. History of the Norwegian schools

- E.g. Waldorf schools in East Germany were closed by the DDR educational authorities, who justified this as follows: the pedagogy was based on the needs of children, rather than on the needs of society, was too pacifistic, and had failed to structure itself according to pure Marxist-Leninist principles."Die Geschichte der Dresdner Waldorfschule"

- The schools founded by 1967 were: Detroit Waldorf School, Green Meadow Waldorf School, High Mowing School, Highland Hall Waldorf School, Honolulu Waldorf School, Kimberton Waldorf School, Rudolf Steiner School of New York City, Sacramento Waldorf School, Waldorf School of Garden City.AWSNA list of schools with dates of founding Archived 21 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Founded in 1968, Toronto Waldorf School was the first Waldorf school in Canada.History of the Toronto Waldorf School Archived 15 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Find a School - Alliance for Public Waldorf Education". www.allianceforpublicwaldorfeducation.org.

- "Different teaching method attracts parents", The New York Times

- Waldorf Schools in Canada | Waldorf ca Archived 4 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Steiner Waldorf Schools Foundation, List of Steiner schools Archived 4 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Connor, Neil (12 March 2012). "China Starts to Question Strict Schooling Methods". Agence France Press – AFP. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

In recent years, China has seen a major expansion of alternative teaching establishments such as those that operate under the educational principles of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner.

- Lin Qi and Guo Shuhan (23 June 2011). "Educating the Whole Child". China Daily. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- Cook, Chris (4 August 2014). "Why are Steiner schools so controversial?". BBC News.

- Thomas Armstrong, PhD (1 December 2006). The Best Schools: How Human Development Research Should Inform Educational Practice. ASCD. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4166-0457-0. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Steiner, Rudolf (2016). "Between Death and Rebirth: Lecture Seven". wn.rsarchive.org. Rudolf Steiner Archive. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Steiner, Rudolf (1973). "Karmic Relationships: Esoteric Studies - Volume VII (Lecture Two)". Rudolf Steiner Archive. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Steiner, Rudolf (1996). The Education of the Child. SteinerBooks. ISBN 9780880109130. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Bowles, Adam (26 March 2000). "Different Teaching Method Attracts Parents". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- Ahern, Geoffrey (2009). Sun at midnight : the Rudolf Steiner movement and gnosis in the West (Rev. and expanded ed.). James Clarke & Co. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0227172933.

- Iona H. Ginsburg, "Jean Piaget and Rudolf Steiner: Stages of Child Development and Implications for Pedagogy", Teachers College Record Volume 84 Number 2, 1982, pp. 327–337.

- Ullrich, Heiner (1994). "Rudolf Steiner". Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education. 24 (3–4): 555–572. doi:10.1007/BF02195288. S2CID 189874700.

- Woods, Philip; Martin Ashley; Glenys Woods (2005). Steiner Schools in England (PDF). UK Department for Education and Skills. ISBN 1-84478-495-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2013.

- As cited in Robert Trostli (ed.), Rhythms of Learning: Selected Lectures by Rudolf Steiner. 1998. p. 44

- Uhrmacher, P. Bruce (Winter 1993). "Making Contact: An Exploration of Focused Attention between Teacher and Students". Curriculum Inquiry. 23 (4): 433–444. doi:10.2307/1180068. JSTOR 1180068.

- Ginsburg and Opper, Piaget's Theory of Intellectual Development, ISBN 0-13-675140-7, pp. 39–40.

- Todd Oppenheimer, Schooling the Imagination, Atlantic Monthly, September 1999.

- Sue Waite; Sarah Rees (2011). Rod Parker-Rees (ed.). Meeting the Child in Steiner Kindergartens: An Exploration of the beliefs, values and practices. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-415-60392-8.

The first epoch (0–7 years), when the child is intensely sensitive to people and surroundings, is seen by Steiner educators as the empathic stage - where empathy means embracing the unconscious of another with one's own unconscious, to live into the experience of another. The kindergarten teacher purposefully employs her own empathic ability as she strives to be a role model worthy of imitation by the children, but she also creates a space and ethos conducive to imaginative play that actively develops children's capacity for empathy.

- Ullrich, Heiner (2008). Rudolf Steiner. London: Continuum International Pub. Group. p. 77. ISBN 9780826484192.

- Taplin, Jill Tina (2010). "Steiner Waldorf Early Childhood Education: Offering a Curriculum for the 21st Century". In Linda Miller, Linda Pound (ed.). Theories and Approaches to Learning in the Early Years. SAGE Publications. p. 92. ISBN 9781849205788. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- Edwards, Carolyn Pope (Spring 2002). "Three Approaches from Europe: Waldorf, Montessori, and Reggio Emilia". Early Childhood Research & Practice. 4 (1).

- Hutchison, David C. (2004). A Natural History of Place in Education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0807744703.

- Nicol, Janni; Taplin, Jill (2012). Understanding the Steiner Waldorf Approach: Early Years Education in Practice. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 9780415597166.

- Ann Gordon and Kathryn Browne, Beginnings & Beyond: Foundations in Early Childhood Education.

- John Siraj-Blatchford; David Whitebread (1 October 2003). Supporting ICT in the Early Years. McGraw-Hill International. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-335-20942-2. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Henk van Oort (2011), "Religious education", Anthroposophy A-Z: A Glossary of Terms Relating to Rudolf Steiner's spiritual philosophy ISBN 9781855842649. p. 99.

- Ida Oberman, "Waldorf History: Case Study of Institutional Memory", Paper presented to Annual Meeting of the American Education Research Association, 24–28 March 1997, published US Department of Education – Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC).

- Willis, Peter and Neville, Bernie, Eds. (1996) Qualitative Research Practice in Adult Education. University of South Australia, Centre for Research in Education Equity and Work ISBN 1-86355-056-9. p. 103.

- Woods, Philip A.; Glenys J. Woods (2006). "In Harmony with the Child: the Steiner teacher as a co-leader in a pedagogical community". FORUM. 48 (3): 319. doi:10.2304/forum.2006.48.3.317.

- R. Murray Thomas, "Levels in education practice", In Encyclopedia of Education and Human Development, Farenga and Ness (eds.). M. E. Sharpe 2005 ISBN 9780765621085. p. 624.

- Gesell, Arnold; Ilg, Frances; Ames, Louise Bates; Bullis, Glenna (1946). The child from five to ten. NY: Harper & Bros. p. 12.

- "Different teaching method attracts parents", The New York Times, 26 March 2000.

- Thomas William Nielsen, "Rudolf Steiner's Pedagogy of Imagination: A Phenomenological Case Study", Peter Lang Publisher 2004.

- Carolyn P. Edwards, "Three Approaches from Europe: Waldorf, Montessori and Reggio Emilia", Early Childhood and Practice, Spring 2002, pp. 7–8.

- Easton, F. (1997). "Educating the whole child, "head, heart, and hands": Learning from the Waldorf experience". Theory into Practice. 36 (2): 87–94. doi:10.1080/00405849709543751. S2CID 55665652.

- Vivienne Walkup, Exploring Education Studies. Taylor and Francis 2011 ISBN 9781408218778. p. 68.

- Christopher Clouder, Martyn Rawson Waldorf Education. Anthroposophic Press:1998. ISBN 9780863153969. p. 26.

- McDermott, R.; Henry, M. E.; Dillard, C.; Byers, P.; Easton, F.; Oberman, I.; Uhrmacher, B. (1996). "Waldorf education in an inner-city public school". The Urban Review. 28 (2): 119. doi:10.1007/BF02354381. S2CID 143544078.

- Martin Ashley (2009). Philip A. Woods; Glenys J. Woods (eds.). Chapter 11: Alternative Education for the 21st Century: Philosophies, Approaches, Visions. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-230-61836-7.

- Helen H. Frink, "Germany", in World Educational Encyclopedia, Rebecca Marlow-Ferguson (ed.), v. 1. Gale 2002 ISBN 0-7876-5578-3. pp. 488–489.

- Ginsberg, Iona H. (1982). "Jean Piaget and Rudolf Steiner:stages of child development and implications for pedagogy". Teachers College Record. 84 (2): 327–337.

- Grant, M. (1999). "Steiner and the Humours: The Survival of Ancient Greek Science". British Journal of Educational Studies. 47: 60. doi:10.1111/1467-8527.00103.

In individuals the temperaments are mixed in the most diverse ways, so that it is possible only to say that one temperament or another predominates in certain traits. Temperament inclines toward the individual, thus making people different, and on the other hand joins individuals together in a group so proving that it has something to do both with the innermost essence of the human being and with universal human nature.

- Ullrich, Heiner (2008). Rudolf Steiner. London: Continuum.

- Sarah W. Whedon (2007). Hands, Hearts, and Heads: Childhood and Esotericism in American Waldorf Education. ISBN 978-0-549-26917-5. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Woods, Philip A.; Martin Ashley; Glenys Woods (2005). Steiner Schools in England. UK Department for Education and Skills (DfES). pp. 89–90.

For example, melancholic children like sitting together because they are unlikely to be annoyed or disturbed by their neighbors. Livelier temperaments such as sanguine or choleric are said to be likely to rub their liveliness off on each other and calm down of their own accord. Little evidence of this aspect of practice was immediately apparent to outside observers, and teachers did not readily volunteer to talk about it.

- Stehlik, Tom (2008). Thinking, Feeling, and Willing: How Waldorf Schools Provide a Creative Pedagogy That Nurtures and Develops Imagination. In Leonard, Timothy and Willis, Peter, Pedagogies of the Imagination: Mythopoetic Curriculum in Educational Practice. Springer. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4020-8350-1. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- Oberski, Iddo (2006). "Learning to Think in Steiner-Waldorf Schools" (PDF). Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology. 5 (3): 336–349. doi:10.1891/194589506787382431. S2CID 144940637. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

-

- "The overarching goal is to help children build a moral impulse within so they can choose in freedom what it means to live morally."—Armon, Joan, "The Waldorf Curriculum as a Framework for Moral Education: One Dimension of a Fourfold System", (Abstract), Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Chicago, IL, 24–28 March 1997), p. 1.

- Peter Schneider, Einführung in die Waldorfpädogogik, Klett-Cotta 1987, ISBN 3-608-93006-X.

- Ronald V. Iannone, Patricia A. Obenauf, "Toward Spirituality in Curriculum and Teaching", page 737, Education, Vol 119 Issue 4, 1999.

- Carnie, Fiona (2003). Alternative approaches to education : a guide for parents and teachers. London: RoutledgeFalmer. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-415-24817-4.

- Miller, Ron (1995). "Freedom in a holistic context". Holistic Education Review. 8 (3): 4–11.

- "Religion or philosophy" SFGate 30 October 2000.

- Suzanne L. Krogh, "Models of Early Childhood Education", In Encyclopedia of Education and Human Development, Farenga and Ness (eds.). M. E. Sharpe 2005. ISBN 9780765621085 p. 484.

- OECD (2005). Formative Assessment Improving Learning in Secondary Classrooms: Improving Assessment in Secondary Classrooms. p. 267.

- Schwartz, Eugene (2000). Waldorf Education: Schools for the Twenty-First Century. Xlibris Corporation. p. 68. ISBN 0738821632.

- Martin Ashley, "Can one teacher know enough to teach Year Six everything? Lessons from Steiner-Waldorf Pedagogy", British Educational Research Association, Annual Conference, University of Glamorgan, 14th – 17th September.

- Nicholson, David W. (2000). "Layers of experience: Forms of representation in a Waldorf school classroom". Journal of Curriculum Studies. 32 (4): 575–587. doi:10.1080/00220270050033637. S2CID 143537628.

- Waldorf Answers.

- Little, William (3 February 2009). "Steiner schools: learning – it is a wonder". The Telegraph. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- Ogeltree, Earl J. (1979). Introduction to Waldorf Education: Curriculum and Methods. University Press of America.

- Leone, Stacie (26 April 2013). "Ithaca Waldorf School: An education based in music, movement and neuroscience". The Ithaca Times. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- Weiner, Irving B.; William Reynolds; Gloria Miller (2012). Handbook of Psychology Vol. 7 Educational Psychology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 241.

- Sumner, Jennifer; Heather Mair; Erin Nelson (2010). "Putting the culture back into agriculture: civic engagement and the celebration of local food". International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability. 1–2 (8): 54–61. doi:10.3763/ijas.2009.0454. S2CID 154772882.

- Leyden, Liz (29 November 2009). "For Forest Kindergarteners, Class is Back to Nature, Rain or Shine". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- Østergaard, Edvin; Dahlin, Bo; Hugo, Aksel (1 September 2008). "Doing phenomenology in science education: a research review" (PDF). Studies in Science Education. 44 (2): 93–121. Bibcode:2008SScEd..44...93O. doi:10.1080/03057260802264081. S2CID 59056009.

- Zubrowski, Bernard (2009). Exploration and Meaning Making in the Learning of Science (Vol. 18 ed.). Springer. p. 231. ISBN 978-90-481-2496-1.

[Pictoral representation] is also a way of focusing attention and closely observing what is happening. However, there are problems when it comes to having students draw. Some are inhibited because they feel they have to have very realistic representations. This can be overcome if throughout the grades drawing is approached both as a way of self-expression and a way of capturing the external world. In Waldorf education, there is an ongoing practice of having students draw. Others would do well to find ways of adapting this approach in public school practice so that drawing is second nature to the students and they are not inhibited in attempting it.

- Thomas Armstrong, cited in Eric Oddleifson, Boston Public Schools As Arts-Integrated Learning Organizations: Developing a High Standard of Culture for All, :"Waldorf education embodies in a truly organic sense all of Howard Gardner's seven intelligences. Rudolph Steiner's vision is a whole one, not simply an amalgam of the seven intelligences. Many schools are currently attempting to construct curricula based on Gardner's model simply through an additive process (what can we add to what we have already got?). Steiner's approach, however, was to begin with a deep inner vision of the child and the child's needs and build a curriculum around that vision."

- Østergaard, Edvin; Dahlin, Bo; Hugo, Aksel (1 September 2008). "Doing phenomenology in science education: a research review". Studies in Science Education. 44 (2): 93–121. Bibcode:2008SScEd..44...93O. doi:10.1080/03057260802264081. S2CID 59056009.

- Fanny Jiminez, "Namen tanzen, fit in Mathe – Waldorf im Vorteil". Die Welt 26 September 2012, citing Barz, et. al, Bildungserfahrungen an Waldorfschulen: Empirische Studie zu Schulqualität und Lernerfahrungen, 2012

- Claudia Schreiner and Ursula Schwantner (2009). "Section 9.6 Comparison of Skills and Individual Characteristics of Waldorf Students". PISA 2006: Austrian Report with a Focus on the Sciences. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2012.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) (in German)

- Scott, Eugenie C. (Winter 1994). "Waldorf Schools Teach Odd Science, Odd Evolution". National Center for Science Education Reports. 14 (4): 20. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- Jelinek, David; Sun, Li-Ling. "Does Waldorf Offer a Viable Form of Science Education? A Research Monograph" (PDF). California State University College of Education. California State University Press. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- Dahlin, Bo (2017). Rudolf Steiner: The Relevance of Waldorf Education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. p. 5. ISBN 9783319589060.

- Woods, Philip A.; Glenys J. Woods (2008). Alternative Education for the 21st Century Philosophies, Approaches, Visions. Palgrave. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-230-60276-2.

There are unresolved conflicts here, principally between a science education based on "inaccurate science" that leads to better scientific understanding.

- Peter Vinthagen Simpson (29 August 2008). "Stockholm University ends Steiner teacher training". The Local.

Stockholm University has decided to wind up its Steiner-Waldorf teacher training. Steiner science literature is 'too much myth and too little fact', the university's teacher education committee has ruled.

- "Reading is a habit that we can't afford to lose", The Herald, 2 December 2007.

- NBC News, "The Waldorf Way: Silicon Valley school eschews technology", 30 November 2011.

- Huffington Post, "Waldorf School Of The Peninsula In California Succeeds With No- And Low-Tech Education", 8 July 2014.

- Bart Jones, Newsday, "Garden City's Waldorf School takes 'no-tech' approach in lower grades", 22 March 2014.

- CBS News, "Silicon Valley school bucks high-tech trend".

- Matt Richtel, "A Silicon Valley School That Doesn’t Compute", The New York Times, 22 October 2011.

- Oberski, Iddo (February 2011). "Rudolf Steiner's philosophy of freedom as a basis for spiritual education?". International Journal of Children's Spirituality. 16 (1): 14. doi:10.1080/1364436x.2010.540751. S2CID 145444483.

- Zander, Helmut (2007). Anthroposophie in Deutschland. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.