Wales in the Roman era

The history of Wales in the Roman era began in 48 AD with a military invasion by the imperial governor of Roman Britain. The conquest was completed by 78, and Roman rule endured until the region was abandoned in AD 383.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Wales |

|

|

|

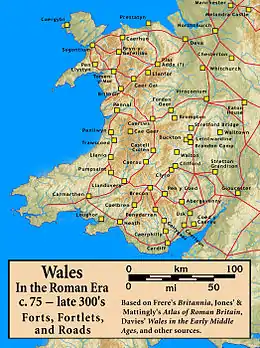

Roman rule in Wales was a military occupation, except for the southern coastal region of South Wales east of the Gower Peninsula, where there is a legacy of Romanisation, and some southern sites such as Carmarthen. The only town in Wales founded by the Romans, Caerwent, is located in South Wales. Wales was a rich source of mineral wealth, and the Romans used their engineering technology to extract large amounts of gold, copper, and lead, as well as modest amounts of some other metals such as zinc and silver.

It is the Roman campaigns of conquest that are most widely known, due to the spirited but unsuccessful defence of their homelands by two native tribes, the Silures and the Ordovices. Aside from the many Roman-related finds along the southern coast, Roman archaeological remains in Wales consist almost entirely of military roads and fortifications.[1]

Britain in AD 47

On the eve of the Roman invasion of Wales, the Roman military under Governor Aulus Plautius was in control of all of southeastern Britain as well as Dumnonia, perhaps including the lowland English Midlands as far as the Dee Estuary and the River Mersey, and having an understanding with the Brigantes to the north.[2] They controlled most of the island's centers of wealth, as well as much of its trade and resources.

In Wales the known tribes (the list may be incomplete) included the Ordovices and Deceangli in the north, and the Silures and Demetae in the south. Archaeology combined with ancient Greek and Roman accounts have shown that there was exploitation of natural resources, such as copper, gold, tin, lead and silver at multiple locations in Britain, including in Wales.[3] Apart from this we have little knowledge of the Welsh tribes of this era.

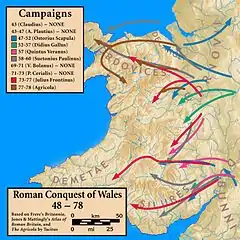

Invasion and conquest

In AD 47 or 48 the new governor, Publius Ostorius Scapula, moved against the Deceangli along the northeastern coast of Wales, devastating their lands.[4] He campaigned successfully but indecisively against the Silures and then the Ordovices, the most notable feature of which is the leadership of both tribes against him by Caratacus.[5] Scapula died in 52, the same year that the resurgent Silures inflicted a defeat on one of the Roman legions.[6] Scapula was succeeded by a number of governors who made steady but inconclusive gains against the two tribes. Gaius Suetonius Paulinus was in the process of conquering Anglesey in AD 60 when the revolt led by Boudica in the east forced a delay in the final conquest of Wales.

There followed a decade of relative peace while Roman imperial attention was focused elsewhere. When expansion into Wales resumed in 73, Roman progress was steady and successful under Sextus Julius Frontinus, who decisively defeated the Silures,[7] followed by the success of Gnaeus Julius Agricola in defeating the Ordovices, and in completing the conquest of Anglesey in AD 77–78.[7][8]

There is no indication of any Roman campaigns against the Demetae, and their territory was not planted with a series of forts, nor overlaid with roads, suggesting that they quickly made their peace with Rome. The main fort in their territory was at Moridunum (modern Carmarthen), built around AD 75, and it eventually became the centre of a Roman civitas. The Demetae were the only pre-Roman Welsh tribe to emerge from Roman rule with their tribal name intact.

Wales in Roman Society

Mining

The mineral wealth of Britain was well-known prior to the Roman invasion and was one of the expected benefits of conquest. All mineral extractions were state-sponsored and under military control, as mineral rights belonged to the emperor.[9] His agents soon found substantial deposits of gold, copper, and lead in Wales, along with some zinc and silver. Gold was mined at Dolaucothi prior to the invasion, but Roman engineering would be applied to greatly increase the amount extracted, and to extract huge amounts of the other metals. This continued until the process was no longer practical or profitable, at which time the mine was abandoned.[10]

Modern scholars have made efforts to quantify the value of these extracted metals to the Roman economy, and to determine the point at which the Roman occupation of Britain was "profitable" to the Empire. While these efforts have not produced deterministic results, the benefits to Rome were substantial. The gold production at Dolaucothi alone may have been of economic significance.[11]

Industrial production

The production of goods for trade and export in Roman Britain was concentrated in the south and east, with virtually none situated in Wales.

This was largely due to circumstance, with iron forges located near iron supplies, pewter (tin with some lead or copper) moulds located near the tin supplies and suitable soil (for the moulds), clusters of pottery kilns located near suitable clayey soil, grain-drying ovens located in agricultural areas where sheep raising (for wool) was also located, and salt production concentrated in its historical pre-Roman locations. Glass-making sites were located in or near urban centres.[10]

In Wales none of the needed materials were available in suitable combination, and the forested, mountainous countryside was not amenable to this kind of industrialisation.

Clusters of tileries, both large and small, were at first operated by the Roman military to meet their own needs, and so there were temporary sites wherever the army went and could find suitable soil. This included a few places in Wales.[12] However, as Roman influence grew, the army was able to obtain tiles from civilian sources who located their kilns in the lowland areas containing good soil, and then shipped the tiles to wherever they were needed.

Romanisation

The Romans occupied the whole of the area now known as Wales, where they built Roman roads and castra, mined gold at Luentinum and conducted commerce, but their interest in the area was limited because of the difficult geography and shortage of flat agricultural land. Most of the Roman remains in Wales are military in nature. Sarn Helen, a major highway, linked the North with South Wales.

The area was controlled by Roman legionary bases at Deva Victrix (modern Chester) and Isca Augusta (Caerleon), two of the three such bases in Roman Britain, with roads linking these bases to auxiliaries' forts such as Segontium (Caernarfon) and Moridunum (Carmarthen).

Furthermore, South-east Wales was the most Romanised part of the country. It is possible that Roman estates in the area survived as recognisable units into the eighth century: the kingdom of Gwent is likely to have been founded by direct descendants of the (romanised) Silurian ruling class [13]'

The best indicators of Romanising acculturation is the presence of urban sites (areas with towns, coloniae, and tribal civitates) and villas in the countryside. In Wales, this can be said only of the southeasternmost coastal region of South Wales. The only civitates in Wales were at Carmarthen and Caerwent.[14] There were three small urban sites near Caerwent, and these and Roman Monmouth were the only other "urbanised" sites in Wales.[15]

In the southwestern homeland of the Demetae, several sites have been classified as villas in the past,[16] but excavation of these and examination of sites as yet unexcavated suggest that they are pre-Roman family homesteads, sometimes updated through Roman technology (such as stone masonry), but having a native character quite different than the true Roman-derived villas that are found to the east, such as in Oxfordshire.[17]

Perhaps surprisingly, the presence of Roman-era Latin inscriptions is not suggestive of full Romanisation. They are most numerous at military sites, and their occurrence elsewhere depended on access to suitable stone and the presence of stonemasons, as well as patronage. The Roman fort complex at Tomen y Mur near the coast of northwestern Wales has produced more inscriptions than either Segontium (near modern Caernarfon) or Noviomagus Reginorum (Chichester).[18]

Hill forts

In areas of civil control, such as the territories of a civitas, the fortification and occupation of hill forts was banned as a matter of Roman policy. However, further inland and northward, a number of pre-Roman hill forts continued to be used in the Roman Era, while others were abandoned during the Roman Era, and still others were newly occupied. The inference is that local leaders who were willing to accommodate Roman interests were encouraged and allowed to continue, providing local leadership under local law and custom.[19]

Religion

There is virtually no evidence to shed light on the practice of religion in Wales during the Roman era, save the anecdotal account of the strange appearance and bloodthirsty customs of the druids of Anglesey by Tacitus during the conquest of Wales.[20] It is fortunate for Rome's reputation that Tacitus described the druids as horrible, else it would be a story of the Roman massacre of defenceless, unarmed men and women. The likelihood of partisan propaganda and an appeal to salacious interests combine to suggest that the account merits suspicion.

The Welsh region of Britain was not significant to the Romanisation of the island and contains almost no buildings related to religious practice, save where the Roman military was located, and these reflect the practices of non-native soldiers. Any native religious sites would have been constructed of wood that has not survived and so are difficult to locate anywhere in Britain, let alone in mountainous, forest-covered Wales.

The time of the arrival of Christianity to Wales is unknown. Archaeology suggests that it came to Roman Britain slowly, gaining adherents among coastal merchants and in the upper classes first, and never becoming widespread outside of the southeast in the Roman Era.[21][22] There is also evidence of a preference for non-Christian devotion in parts of Britain, such as in the upper regions of the Severn Estuary in the 4th century, from the Forest of Dean east of the River Wye continuously around the coast of the estuary, up to and including Somerset.[23]

In the De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, written c. 540, Gildas provides a story of the martyrdom of Saint Alban at Verulamium, and of Julius and Aaron at Legionum Urbis, the 'City of the Legion', saying that this occurred during a persecution of Christians at a time when 'decrees' against them were issued.[24] Bede repeats the story in his Ecclesiastical History, written c. 731.[25] The otherwise unspecified 'City of the Legion' is arguably Caerleon, Welsh Caerllion, the 'Fortress of the Legion', and the only candidate with a long and continuous military presence that lay within a Romanised region of Britain, with nearby towns and a Roman civitas. Other candidates are Chester and Carlisle, though both were located far from the Romanised area of Britain and had a transitory, more military-oriented history.

A parenthetical note concerns Saint Patrick, a patron saint of Ireland. He was a Briton born c. 387 in Banna Venta Berniae, a location that is unknown due to the transcription errors in surviving manuscripts. His home is a matter of conjecture, with sites near Carlisle farvoured by some,[26] while coastal South Wales is favoured by others.[27]

Irish settlement

By the middle of the 4th century the Roman presence in Britain was no longer vigorous. Once-unfortified towns were now being surrounded by defensive walls, including both Carmarthen and Caerwent.[28] Political control finally collapsed and a number of alien tribes then took advantage of the situation, raiding widely throughout the island, joined by Roman soldiers who had deserted and by elements of the native Britons themselves.[29] Order was restored in 369, but Roman Britain would not recover.

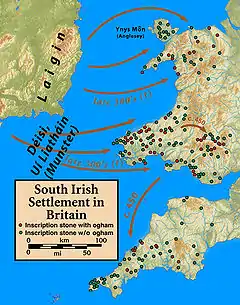

It was at this time[30] that Wales received an infusion of settlers from southern Ireland, the Uí Liatháin, Laigin, and possibly Déisi,[31][32][33] the last no longer seen as certain, with only the first two verified by reliable sources and place-name evidence. The Irish were concentrated along the southern and western coasts, in Anglesey and Gwynedd (excepting the cantrefi of Arfon and Arllechwedd), and in the territory of the Demetae.

The circumstances of their arrival are unknown, and theories include categorising them as "raiders", as "invaders" who established a hegemony, and as "foederati" invited by the Romans. It might as easily have been the consequence of a depopulation in Wales caused by plague or famine, both of which were usually ignored by ancient chroniclers.

What is known is that their characteristically Irish circular huts are found where they settled; that the inscription stones found in Wales, whether in Latin or ogham or both, are characteristically Irish; that when both Latin and ogham are present on a stone, the name in the Latin text is given in Brittonic form while the same name is given in Irish form in ogham;[34] and that medieval Welsh royal genealogies include Irish-named ancestors[35][36] who also appear in the native Irish narrative The Expulsion of the Déisi.[37] This phenomenon may however be the result of later influences and again only the presence of the Uí Liatháin and Laigin in Wales has been verified.

End of the Roman era

Historical accounts tell of the upheavals in the Roman Empire during the 3rd and 4th centuries, with notice of the withdrawal of troops from Roman Britain in support of the imperial ambitions of Roman generals stationed there. In much of Wales, where Roman troops were the only indication of Roman rule, that rule ended when troops left and did not return. The end came to different regions at different times.

Tradition holds that Roman customs held on for several years in southern Wales, lasting into the end of the 5th century and early 6th century, and that is true in part. Caerwent continued to be occupied after the Roman departure, while Carmarthen was probably abandoned in the late 4th century.[38] In addition, southwestern Wales was the tribal territory of the Demetae, who had never become thoroughly Romanised. The entire region of southwestern Wales had been settled by Irish newcomers in the late 4th century, and it seems far-fetched to suggest that they were ever fully Romanised.

However in the southeast Wales, following the withdrawal of the Roman legions from Britain, the town of Venta Silurum (Caerwent) remained occupied by Romano-Britons until at least the early sixth century: Early Christian worship was still established in the town, that might have had a bishop with a monastery in the second half of that century.

Magnus Maximus

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In Welsh literary tradition, Magnus Maximus is the central figure in the emergence of a free Britain in the post-Roman era. Royal and religious genealogies compiled in the Middle Ages have him as the ancestor of kings and saints.[35][36] In the Welsh story of Breuddwyd Macsen Wledig (The Dream of Emperor Maximus), he is Emperor of Rome and marries a wondrous British woman, telling her that she may name her desires, to be received as a wedding portion. She asks that her father be given sovereignty over Britain, thus formalising the transfer of authority from Rome back to the Britons themselves.

Historically Magnus Maximus was a Roman general who served in Britain in the late 4th century, launching his successful bid for imperial power from Britain in 383. This is the last date for any evidence of a Roman military presence in Wales, the western Pennines, and Deva (i.e., the entire non-Romanised region of Britain south of Hadrian's Wall). Coins dated later than 383 have been excavated along the Wall, suggesting that troops were not stripped from it, as was once thought.[39] In the De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae written c. 540, Gildas says that Maximus left Britain not only with all of its Roman troops, but also with all of its armed bands, governors, and the flower of its youth, never to return.[40] Having left with the troops and senior administrators, and planning to continue as the ruler of Britain, his practical course was to transfer local authority to local rulers. Welsh legend provides a mythic story that says he did exactly that.

After he became emperor of the Western Roman Empire, Maximus would return to Britain to campaign against the Picts and Scots (i.e., Irish), probably in support of Rome's long-standing allies the Damnonii, Votadini, and Novantae (all located in modern Scotland). While there he likely made similar arrangements for a formal transfer of authority to local chiefs: the later rulers of Galloway, home to the Novantae, would claim Maximus as the founder of their line, the same as did the Welsh kings.[39]

Maximus would rule the Roman West until he was killed in 388. A succession of governors would rule southeastern Britain until 407, but there is nothing to suggest that any Roman effort was made to regain control of the west or north after 383, and that year would be the definitive end of the Roman era in Wales.

Legacy

Wendy Davies has argued that the later medieval Welsh approach to property and estates was a Roman legacy, but this issue and others related to legacy are not yet resolved. For example, Leslie Alcock has argued that that approach to property and estates cannot pre-date the 6th century and is thus post-Roman.[41]

There was little Latin linguistic heritage left to the Welsh language, only a number of borrowings from the Latin lexicon. With the absence of early written Welsh sources there is no way of knowing when these borrowings were incorporated into Welsh, and may date from a later post-Roman era when the language of literacy was still Latin. Borrowings include a few common words and word forms. For example, Welsh ffenestr is from Latin fenestra, 'window'; llyfr is from liber, 'book'; ysgrif is from scribo, 'scribe'; and the suffix -wys found in Welsh folk names is derived from the Latin suffix -ēnsēs.[42][43] There are a few military terms, such as caer from Latin castra, 'fortress'. Eglwys, meaning 'church', is ultimately derived from the Greek klēros.

Welsh kings would later use the authority of Magnus Maximus as the basis of their inherited political legitimacy. While imperial Roman entries in Welsh royal genealogies lack any historical foundation, they serve to illustrate the belief that legitimate royal authority began with Magnus Maximus. As told in The Dream of Emperor Maximus, Maximus married a Briton, and their supposed children are given in genealogies as the ancestors of kings. Tracing ancestries back further, Roman emperors are listed as the sons of earlier Roman emperors, thus incorporating many famous Romans (e.g., Constantine the Great) into the royal genealogies.

The kings of medieval Gwynedd trace their origins to the northern British kingdom of Manaw Gododdin (located in modern Scotland), and they also claim a connection to Roman authority in their genealogies ("Eternus son of Paternus son of Tacitus"). This claim may be either an independent one, or was perhaps an invention intended to rival the legitimacy of kings claiming descent from the historical Maximus.

Gwyn A. Williams argues that even at the time of the erection of Offa's Dyke (that divided Wales from medieval England) the people to its west saw themselves as "Roman", citing the number of Latin inscriptions still being made into the 8th century.[44]

Citations

- "A History of Wales", by Sir John Edward LLoyd

- Jones 1990:43–67, An Atlas of Roman Britain, Britain Before the Conquest, and The Conquest and Garrisoning of Britain.

- Jones 1990:179–195, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Economy.

- Tacitus:228, Annals XII, where they are referred to as the 'Cangi'.

- Tacitus 117:228, Annals XXIII

- Davies 1990:28, History of Wales, Wales and Rome

- Davies 1990:29, History of Wales, Wales and Rome

- Tacitus 117:600, Life of Agricola XVIII

- Jones 1990:179, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Economy

- Jones 1990:179–196, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Economy

- Jones 1990:180, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Economy

- Jones 1990:217, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Economy: The distribution of tileries

- Roman Wales on the RCAHMW website: early Medioeval times

- Jones 1990:154, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Development of the Provinces.

- Jones 1990:156, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Development of the Provinces.

- Jones 1990:241, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Countryside.

- Jones 1990:251, 254, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Countryside: Dyfed.

- Jones 1990:153, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Development of the Provinces: Latin Inscriptions and Language.

- Laing 1990:112–113, Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 200–800, The non-Romanized zone of Britannia.

- Tacitus:257, Annals, Bk. XIV, Ch. XXX.

- Jones 1990:264–305, An Atlas of Roman Britain, Religion.

- Frere 1987:324, Britannia, The Romanisation of Britain.

- Jones 1990:299, An Atlas of Roman Britain, Religion.

- Giles 1841:11–12, The Works of Gildas, The History, ch. 10. The 'City of the Legion' is not specified in the original Latin. This translator, for whatever reason, chooses Carlisle.

- Bede (731), "Ecclesiastical History, Ch. VIII", in Giles, J. A. (ed.), The Miscellaneous Works of Venerable Bede, II, London: Whittaker and Co. (published 1863), p. 53

- De Paor, Liam (1993), Saint Patrick's World: The Christian Culture of Ireland's Apostolic Age, Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 88 and 96, ISBN 1-85182-144-9

- MacNeill, Eoin (1926), "The Native Place of St. Patrick", Papers read for the Royal Irish Academy, Dublin: Hodges, Figgis, pp. 118–140. MacNeill argues that the southern coast of Wales offered both numerous slaves and quick access to booty, and as the region was also home to Irish settlers, raiders would have had the contacts to tell them precisely where to go in order to quickly obtain booty and capture slaves. MacNeill also suggests a possible home town based on naming similarities, but allows that the transcription errors in manuscripts make this little more than an educated guess.

- Jones 1990:162, An Atlas of Roman Britain, The Development of the Provinces.

- Yonge, C. D., ed. (1894), The Roman History of Ammianus Marcellinus, London: George Bell & Sons: p.413, Ammianus 26.4.5 Trans.; pp. 453–455, Ammianus 27.8 Trans.; pp 483–485, Ammianus 28.3 Trans.

- Laing 1975:93, Early Celtic Britain and Ireland, Wales and the Isle of Man.

- Miller, Mollie (1977), "Date-Guessing and Dyfed", Studia Celtica, 12, Cardiff: University of Wales, pp. 33–61

- Coplestone-Crow, Bruce (1981), "The Dual Nature of Irish Colonization of Dyfed in the Dark Ages", Studia Celtica, 16, Cardiff: University of Wales, pp. 1–24

- Meyer, Kuno (1896), "Early Relations Between Gael and Brython", in Evans, E. Vincent (ed.), Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, Session 1895–1896, I, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 55–86

- Rhys, John (1895). Archaeologia Cambrensis. W. Pickering., pp 307–313

- Phillimore, Egerton, ed. (1887), "Pedigrees from Jesus College MS. 20", Y Cymmrodor, VIII, Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 83–92

- Phillimore, Egerton (1888), "The Annales Cambriae and Old Welsh Genealogies, from Harleian MS. 3859", in Phillimore, Egerton (ed.), Y Cymmrodor, IX, Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 141–183

- Meyer, Kuno, ed. (1901), "The Expulsion of the Dessi", Y Cymmrodor, XIV, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 101–135

- Laing 1990:108, Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 200–800, The non-Romanized zone of Britannia.

- Frere 1987:354, Britannia, The End of Roman Britain.

- Giles 1841:13, The Works of Gildas, The History, ch. 14

- Laing 1990:112, Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 200–800, The non-Romanized zone of Britannia.

- Koch, John. The Gododdin of Aneirin, Celtic Studies Publications, 1997, p. 133.

- Maund 2006, p. 16, n.2

- Williams, Gwyn A., The Welsh in their History, published 1982 by Croom Helm, ISBN 0-7099-3651-6

References

- Davies, John (1990), A History of Wales (First ed.), London: Penguin Group (published 1993), ISBN 0-7139-9098-8

- Davies, Wendy (1982), Wales in the Early Middle Ages, Leicester: Leicester University Press, ISBN 0-7185-1235-9

- Frere, Sheppard Sunderland (1987), Britannia: A History of Roman Britain (3rd, revised ed.), London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7102-1215-1

- Giles, John Allen, ed. (1841), "The Works of Gildas", The Works of Gildas and Nennius, London: James Bohn

- Jones, Barri; Mattingly, David (1990), An Atlas of Roman Britain, Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers (published 2007), ISBN 978-1-84217-067-0

- Laing, Lloyd (1975), "Wales and the Isle of Man", The Archaeology of Late Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 400–1200 AD, Frome: Book Club Associates (published 1977), pp. 89–119

- Laing, Lloyd; Laing, Jennifer (1990), "The non-Romanized zone of Britannia", Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 200–800, New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 96–123, ISBN 0-312-04767-3

- Lloyd, John Edward (1911), A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, I (2nd ed.), London: Longmans, Green, and Co (published 1912)

- Mattingly, David (2006), An Imperial Possession: Britain in the Roman Empire, London: Penguin Books (published 2007), ISBN 978-0-14-014822-0

- Maund, Kari (2000), The Welsh Kings. Warriors, Warlords and Princes, Stroud: Tempus Publishing (published 2006), ISBN 0-7524-2973-6

- Rhys, John (1904), Celtic Britain (3rd ed.), London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge

- Snyder, Christopher A. (1998), An Age of Tyrants: Britain and the Britons A.D. 400–600, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, ISBN 0-271-01780-5

- Tacitus, Publius Cornelius (117), Murphy, Arthur (ed.), The Works of Cornelius Tacitus (English translation) (New ed.), London: Jones & Co. (published 1836)

External links

- Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales

- Roman Wales on the RCAHMW website

- Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust info on Roman Wales

- 58 pages of artifacts and places associated with Roman Wales on Gathering the Jewels the website of Welsh cultural history

- Iron Age and Roman Coins in Wales : A study by Cardiff University

- Map of Roman localities in Wales (click on the arrows to get detailed information