Isles of Scilly

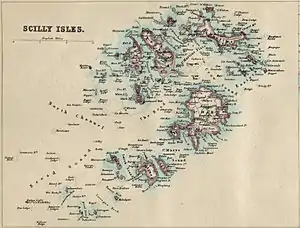

The Isles of Scilly (/ˈsɪli/; Cornish: Syllan or Enesek Syllan) is an archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall. One of the islands, St Agnes, is the most southerly point in England, being over 4 miles (6.4 km) further south than the most southerly point of the British mainland at Lizard Point.

| Syllan | |

|---|---|

The Isles of Scilly, viewed from the International Space Station | |

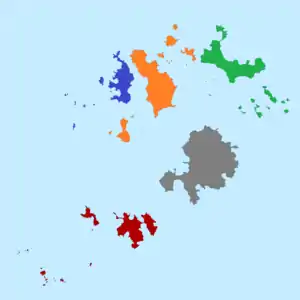

The Isles of Scilly (red; bottom left corner) within Cornwall (red & beige) | |

| Geography | |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 49°56′10″N 6°19′22″W |

| OS grid reference | 25 |

| Archipelago | British Isles |

| Adjacent bodies of water | Celtic Sea Atlantic Ocean |

| Total islands | 5 inhabited, 140 others |

| Major islands | |

| Area | 16.37 km2 (6.32 sq mi) (314th) |

| Administration | |

| Status | Sui generis unitary |

| Country | England |

| Region | South West |

| Ceremonial county | Cornwall |

| Largest settlement | Hugh Town (pop. 1,097) |

| Leadership | Councillor Robert Francis[1] |

| Executive | Mark Boden (interim)[2] |

| MP | Derek Thomas (C) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 2,224 (mid-2019 est. · 314th) |

| Pop. density | 139/km2 (360/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | 97.3% White British 2.4% Other White 0.3% Mixed[3] |

| Additional information | |

| Official website | www |

| Designated | 13 August 2001 |

| Reference no. | 1095[4] |

The total population of the islands at the 2011 census was 2,203.[5] Scilly forms part of the ceremonial county of Cornwall, and some services are combined with those of Cornwall. However, since 1890, the islands have had a separate local authority. Since the passing of the Isles of Scilly Order 1930, this authority has had the status of a county council and today is known as the Council of the Isles of Scilly.

The adjective "Scillonian" is sometimes used for people or things related to the archipelago. The Duchy of Cornwall owns most of the freehold land on the islands. Tourism is a major part of the local economy, along with agriculture—particularly the production of cut flowers.

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the British Isles |

|

Early history

The islands may correspond to the Cassiterides ('Tin Isles') believed by some to have been visited by the Phoenicians, and mentioned by the Greeks. However, the archipelago itself does not contain much tin.

The isles were off the coast of the Brittonic Celtic kingdom of Dumnonia and later its offshoot, Kernow (Cornwall), and may have been a part of these polities until their conquest by the English in the 10th century AD.

It is likely that until relatively recent times the islands were much larger and perhaps joined together into one island named Ennor. Rising sea levels flooded the central plain around 400–500 AD, forming the current 55 islands and islets, if an island is defined as "land surrounded by water at high tide and supporting land vegetation".[6] The word Ennor is a contraction of the Old Cornish[7] En Noer (Moer, mutated to Noer), meaning 'the land'[7] or the 'great island'.[8]

Evidence for the older large island includes:

- A description written during Roman times designates Scilly "Scillonia insula" in the singular, indicating either a single island or an island much bigger than any of the others.

- Remains of a prehistoric farm have been found on Nornour, which is now a small rocky skerry far too small for farming.[9][10] There once was an Iron Age British community here that extended into Roman times.[10] This community was likely formed by immigrants from Brittany, probably the Veneti who were active in the tin trade that originated in mining activity in Cornwall and Devon.

- At certain low tides the sea becomes shallow enough for people to walk between some of the islands.[11] This is possibly one of the sources for stories of drowned lands, e.g. Lyonesse.

- Ancient field walls are visible below the high tide line off some of the islands (e.g. Samson).

- Some of the Cornish language place names also appear to reflect past shorelines, and former land areas.[12]

- The whole of southern England has been steadily sinking in opposition to post-glacial rebound in Scotland: this has caused the rias (drowned river valleys) on the southern Cornish coast, e.g. River Fal and the Tamar Estuary.[10]

Offshore, midway between Land's End and the Isles of Scilly, is the supposed location of the mythical lost land of Lyonesse, referred to in Arthurian literature, of which Tristan is said to have been a prince. This may be a folk memory of inundated lands, but this legend is also common among the Brythonic peoples; the legend of Ys is a parallel and cognate legend in Brittany as is that of Cantre'r Gwaelod in Wales.

Scilly has been identified as the place of exile of two heretical 4th century bishops, Instantius and Tiberianus, who were followers of Priscillian.[13]

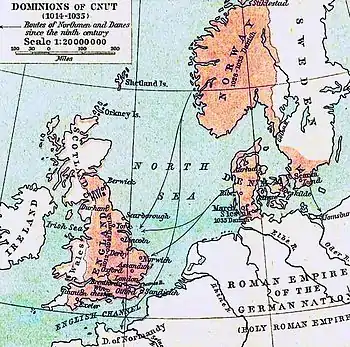

Norse and Norman period

In 995, Olaf Tryggvason became King Olaf I of Norway. Born c. 960, Olaf had raided various European cities and fought in several wars. In 986 he met a Christian seer on the Isles of Scilly. He was probably a follower of Priscillian and part of the tiny Christian community that was exiled here from Spain by Emperor Maximus for Priscillianism. In Snorri Sturluson's Royal Sagas of Norway, it is stated that this seer told him:

Thou wilt become a renowned king, and do celebrated deeds. Many men wilt thou bring to faith and baptism, and both to thy own and others' good; and that thou mayst have no doubt of the truth of this answer, listen to these tokens. When thou comest to thy ships many of thy people will conspire against thee, and then a battle will follow in which many of thy men will fall, and thou wilt be wounded almost to death, and carried upon a shield to thy ship; yet after seven days thou shalt be well of thy wounds, and immediately thou shalt let thyself be baptised.

The legend continues that, as the seer foretold, Olaf was attacked by a group of mutineers upon returning to his ships. As soon as he had recovered from his wounds, he let himself be baptised. He then stopped raiding Christian cities, and lived in England and Ireland. In 995, he used an opportunity to return to Norway. When he arrived, the Haakon Jarl was facing a revolt. Olaf Tryggvason persuaded the rebels to accept him as their king, and Jarl Haakon was murdered by his own slave, while he was hiding from the rebels in a pig sty.

With the Norman Conquest, the Isles of Scilly came more under centralised control. About 20 years later, the Domesday survey was conducted. The islands would have formed part of the "Exeter Domesday" circuit, which included Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, and Wiltshire.

In the mid-12th century, there was reportedly a Viking attack on the Isles of Scilly, called Syllingar by the Norse,[14] recorded in the Orkneyinga saga— Sweyn Asleifsson "went south, under Ireland, and seized a barge belonging to some monks in Syllingar and plundered it."[14] (Chap LXXIII)

...the three chiefs—Swein, Þorbjörn and Eirik—went out on a plundering expedition. They went first to the Suðreyar [Hebrides], and all along the west to the Syllingar, where they gained a great victory in Maríuhöfn on Columba's-mass [9 June], and took much booty. Then they returned to the Orkneys.[14]

"Maríuhöfn" literally means "Mary's Harbour/Haven". The name does not make it clear if it referred to a harbour on a larger island than today's St Mary's, or a whole island.

It is generally considered that Cornwall, and possibly the Isles of Scilly, came under the dominion of the English Crown late in the reign of Æthelstan (r. 924–939). In early times one group of islands was in the possession of a confederacy of hermits. King Henry I (r. 1100–35) gave it to the abbey of Tavistock who established a priory on Tresco, which was abolished at the Reformation.[15]

Later Middle Ages and early modern period

At the turn of the 14th century, the Abbot and convent of Tavistock Abbey petitioned the king,

stat[ing] that they hold certain isles in the sea between Cornwall and Ireland, of which the largest is called Scilly, to which ships come passing between France, Normandy, Spain, Bayonne, Gascony, Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Cornwall: and, because they feel that in the event of a war breaking out between the kings of England and France, or between any of the other places mentioned, they would not have enough power to do justice to these sailors, they ask that they might exchange these islands for lands in Devon, saving the churches on the islands appropriated to them.[16]

William le Poer, coroner of Scilly, is recorded in 1305 as being worried about the extent of wrecking in the islands, and sending a petition to the King. The names provide a wide variety of origins, e.g. Robert and Henry Sage (English), Richard de Tregenestre (Cornish), Ace de Veldre (French), Davy Gogch (possibly Welsh, or Cornish), and Adam le Fuiz Yaldicz (Spanish?).

It is not known at what point the islanders stopped speaking the Cornish language, but the language seems to have gone into decline in Cornwall beginning in the Late Middle Ages; it was still dominant between the islands and Bodmin at the time of the Reformation, but it suffered an accelerated decline thereafter. The islands appear to have lost the old Celtic language before parts of Penwith on the mainland, in contrast to the history of Irish or Scottish Gaelic.

During the English Civil War, the Parliamentarians captured the isles, only to see their garrison mutiny and return the isles to the Royalists. By 1651 the Royalist governor, Sir John Grenville, was using the islands as a base for privateering raids on Commonwealth and Dutch shipping. The Dutch admiral Maarten Tromp sailed to the isles and on arriving on 30 May 1651 demanded compensation. In the absence of compensation or a satisfactory reply, he declared war on England in June. It was during this period that the Three Hundred and Thirty Five Years' War started between the isles and the Netherlands.

In June 1651, Admiral Robert Blake recaptured the isles for the Parliamentarians. Blake's initial attack on Old Grimsby failed, but the next attacks succeeded in taking Tresco and Bryher. Blake placed a battery on Tresco to fire on St Mary's, but one of the guns exploded, killing its crew and injuring Blake. A second battery proved more successful. Subsequently, Grenville and Blake negotiated terms that permitted the Royalists to surrender honourably. The Parliamentary forces then set to fortifying the islands. They built Cromwell's Castle—a gun platform on the west side of Tresco—using materials scavenged from an earlier gun platform further up the hill. Although this poorly sited earlier platform dated back to the 1550s, it is now referred to as King Charles's Castle.

The Isles of Sicily served as a place of exile during the English Civil War. Among those exiled there was Unitarian Jon Biddle.[17]

During the night of 22 October 1707, the isles were the scene of one of the worst maritime disasters in British history, when out of a fleet of 21 Royal Navy ships headed from Gibraltar to Portsmouth, six were driven onto the cliffs. Four of the ships sank or capsized, with at least 1,450 dead, including the commanding admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell.

There is evidence for inundation by the tsunami caused by the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.[18]

The islands appear to have been raided frequently by Barbary pirates to enslave residents to support the Barbary slave trade.[19]

Governors of Scilly

An early governor of Scilly was Thomas Godolphin, whose son Francis received a lease on the Isles in 1568. They were styled Governors of Scilly and the Godolphins and their Osborne relatives held this position until 1834. In 1834 Augustus John Smith acquired the lease from the Duchy for £20,000.[20] Smith created the title Lord Proprietor of the Isles of Scilly for himself, and many of his actions were unpopular. The lease remained in his family until it expired for most of the Isles in 1920 when ownership reverted to the Duchy of Cornwall. Today, the Dorrien-Smith estate still holds the lease for the island of Tresco.

- 1568–1608 Sir Francis Godolphin (1540–1608)

- 1608–1613 Sir William Godolphin of Godolphin (1567–1613)

- 1613–1636 William Godolphin (1611–1636)

- 1636–1643 Sidney Godolphin (1610–1643)

- 1643–1646 Sir Francis Godolphin of Godolphin (1605–1647)

- 1647–1648 Anthony Buller (Parliamentarian)

- 1649–1651 Sir John Grenville (Royalist)

- 1651–1660 Joseph Hunkin[21] (Parliamentary control)

- 1660–1667 Sir Francis Godolphin of Godolphin (1605–1667) (restored to office)

- 1667–1700 Sidney Godolphin, 1st Earl of Godolphin (1645–1712)

- 1700–1732 Sidney Godolphin (1652–1732)

- 1733–1766 Francis Godolphin, 2nd Earl of Godolphin (1678–1766)

- 1766–1785 Francis Godolphin, 2nd Baron Godolphin (1706–1785)

- 1785–1799 Francis Osborne, 5th Duke of Leeds (1751–1799)

- 1799–1831 George Osborne, 6th Duke of Leeds (1775–1838)

- 1834–1872 Augustus John Smith (1804–1872)

- 1872–1918 Thomas Algernon Smith-Dorrien-Smith (1846–1918)

- 1918–1920 Arthur Algernon Dorrien-Smith (1876–1955)

Geography

The Isles of Scilly form an archipelago of five inhabited islands (six if Gugh is counted separately from St Agnes) and numerous other small rocky islets (around 140 in total) lying 45 km (28 mi) off Land's End.[22]

The islands' position produces a place of great contrast; the ameliorating effect of the sea, greatly influenced by the North Atlantic Current, means they rarely have frost or snow, which allows local farmers to grow flowers well ahead of those in mainland Britain. The chief agricultural product is cut flowers, mostly daffodils. Exposure to Atlantic winds also means that spectacular winter gales lash the islands from time to time. This is reflected in the landscape, most clearly seen on Tresco where the lush Abbey Gardens on the sheltered southern end of the island contrast with the low heather and bare rock sculpted by the wind on the exposed northern end.

Natural England has designated the Isles of Scilly as National Character Area 158.[23] As part of a 2002 marketing campaign, the plant conservation charity Plantlife chose sea thrift (Armeria maritima) as the "county flower" of the islands.[9][24]

This table provides an overview of the most important islands:

| Island | Population (Census 2001) |

Area (km2) | Density | Main settlement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St Mary's | 1,666 | 6.58 | 253.2 | Hugh Town |

| Tresco | 180 | 2.97 | 60.6 | New Grimsby |

| St Martin's (with White Island) | 142 | 2.37 | 60 | Higher Town |

| St Agnes (with Gugh) | 73 | 1.48 | 49.3 | Middle Town |

| Bryher (with Gweal) | 92 | 1.32 | 70 | The Town |

| Samson | -(1) | 0.38 | - | |

| Annet | – | 0.21 | - | |

| St. Helen's | – | 0.20 | - | |

| Teän | – | 0.16 | - | |

| Great Ganilly | – | 0.13 | - | |

| remaining 45 islets | – | 0.57 | - | |

| Isles of Scilly | 2,153 | 16.37 | Hugh Town |

(1) Inhabited until 1855.

In 1975 the islands were designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The designation covers the entire archipelago, including the uninhabited islands and rocks, and is the smallest such area in the UK. The islands of Annet and Samson have large terneries and the islands are well populated by seals. The Isles of Scilly are the only British haunt of the lesser white-toothed shrew (Crocidura suaveolens), where it is known locally as a "teak" or "teke".[25]

The islands are famous among birdwatchers for their ability to attract rare birds from all corners of the globe. The peak time of year for this is generally in October when it is not unusual for several of the rarest birds in Europe to share this archipelago. One reason for the success of these islands in producing rarities is the extensive coverage these islands get from birdwatchers, but archipelagos are often favoured by rare birds which like to make landfall and eat there before continuing their journeys and often arrive on far-flung islands first.

Tidal influx

The tidal range at the Isles of Scilly is high for an open sea location; the maximum for St Mary's is 5.99 m (19.7 ft). Additionally, the inter-island waters are mostly shallow, which at spring tides allows for dry land walking between several of the islands. Many of the northern islands can be reached from Tresco, including Bryher, Samson and St Martin's (requires very low tides). From St Martin's White Island, Little Ganilly and Great Arthur are reachable. Although the sound between St Mary's and Tresco, The Road, is fairly shallow, it never becomes totally dry, but according to some sources it should be possible to wade at extreme low tides. Around St Mary's several minor islands become accessible, including Taylor's Island on the west coast and Tolls Island on the east coast. From Saint Agnes, Gugh becomes accessible at each low tide, via a tombolo.

Climate

| St. Mary's Heliport (1981–2010)[26] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Isles of Scilly have a temperate Oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), closely bordering a subtropical climate.[27] The average annual temperature is 11.8 °C (53.2 °F), by far the warmest place in the British Isles. Winters are, by far, the warmest in the country due to the moderating effects of the ocean, and despite being on exactly the same latitude as Winnipeg in Canada, snow and frost are extremely rare. The maximum snowfall was 23 cm (9 in) on 12 January 1987.[28] Summers are not as warm as on the mainland. The Scilly Isles are one of the sunniest areas in the southwest with on average 7 hours per day in May. The lowest temperature ever recorded was −7.2 °C (19.0 °F) and the highest was 27.8 °C (82.0 °F).[29] The isles have never recorded a temperature below freezing between May and November. Precipitation (the overwhelming majority of which is rain) averages about 34 inches per year. The wettest months are from October to January, while May and June are the driest months.

| Climate data for St Mary's Heliport, 1981–2010 averages | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.7 (49.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.7 (58.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

7.9 (46.2) |

8.8 (47.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

12.7 (54.9) |

10.3 (50.5) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.2 (43.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

8.5 (47.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.2 (19.0) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

8.6 (47.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 94.8 (3.73) |

69.7 (2.74) |

61.7 (2.43) |

54.6 (2.15) |

47.8 (1.88) |

47.8 (1.88) |

63.4 (2.50) |

67.2 (2.65) |

67.4 (2.65) |

96.6 (3.80) |

95.9 (3.78) |

98.2 (3.87) |

865.1 (34.06) |

| Average precipitation days | 14.5 | 13.0 | 11.5 | 10.4 | 8.5 | 6.9 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 10.2 | 14.4 | 14.9 | 15.2 | 138.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 58.8 | 79.8 | 124.4 | 192.4 | 218.5 | 206.3 | 204.1 | 203.4 | 160.1 | 113.0 | 74.6 | 54.4 | 1,689.8 |

| Source: Met Office[30] | |||||||||||||

Geology

_(14754540266).jpg.webp)

All the islands of Scilly are all composed of granite rock of Early Permian age, an exposed part of the Cornubian batholith. The Irish Sea Glacier terminated just to the north of the Isles of Scilly during the last Ice Age.[31][32]

Fauna

Government

National government

Politically, the islands are part of England, one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. They are represented in the UK Parliament as part of the St Ives constituency. As part of the United Kingdom, the islands were part of the European Union and were represented in the European Parliament as part of the multi-member South West England constituency.

Local government

Historically, the Isles of Scilly were administered as one of the hundreds of Cornwall, although the Cornwall quarter sessions had limited jurisdiction there. For judicial purposes, shrievalty purposes, and lieutenancy purposes, the Isles of Scilly are "deemed to form part of the county of Cornwall".[33] The archipelago is part of the Duchy of Cornwall[34] – the duchy owns the freehold of most of the land on the islands and the duke exercises certain formal rights and privileges across the territory, as he does in Cornwall proper.

The Local Government Act 1888 allowed the Local Government Board to establish in the Isles of Scilly "councils and other local authorities separate from those of the county of Cornwall"... "for the application to the islands of any act touching local government." Accordingly, in 1890 the Isles of Scilly Rural District Council (the RDC) was formed as a sui generis unitary authority, outside the administrative county of Cornwall. Cornwall County Council provided some services to the Isles, for which the RDC made financial contributions. The Isles of Scilly Order 1930[35] granted the council the "powers, duties and liabilities" of a county council. Section 265 of the Local Government Act 1972 allowed for the continued existence of the RDC, but renamed as the Council of the Isles of Scilly.[36][37]

This unusual status also means that much administrative law (for example relating to the functions of local authorities, the health service and other public bodies) that applies in the rest of England applies in modified form in the islands.[38]

The Council of the Isles of Scilly is a separate authority to the Cornwall Council unitary authority, and as such the islands are not part of the administrative county of Cornwall. However the islands are still considered to be part of the ceremonial county of Cornwall.

With a total population of just over 2,000, the council represents fewer inhabitants than many English parish councils, and is by far the smallest English unitary council. As of 2015, 130 people are employed full-time by the council[39] to provide local services (including water supply and air traffic control). These numbers are significant, in that almost 10% of the adult population of the islands is directly linked to the council, as an employee or a councillor.[40]

The Council consists of 21 elected councillors—13 of whom are returned by the ward of St Mary's, and two from each of four "off-island" wards (St Martin's, St Agnes, Bryher, and Tresco). The latest elections took place on 2 May 2013; all 20 elected were independents (one seat remained vacant).[41]

The council is headquartered at Town Hall, by The Parade park in Hugh Town, and also performs the administrative functions of the AONB Partnership[42] and the Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority.[43]

Some aspects of local government are shared with Cornwall, including health, and the Council of the Isles of Scilly together with Cornwall Council form a Local Enterprise Partnership. In July 2015 a devolution deal was announced by the government under which Cornwall Council and the Council of the Isles of Scilly are to create a plan to bring health and social care services together under local control. The Local Enterprise Partnership is also to be bolstered.[44]

Flags

Two flags are used to represent Scilly:

- The Scillonian Cross, selected by readers of Scilly News in a 2002 vote and then registered with the Flag Institute as the flag of the islands.[45][46][47]

- The flag of the Council of the Isles of Scilly, which incorporates the council's logo and represents the council.[45]

An adapted version of the old Board of Ordnance flag has also been used, after it was left behind when munitions were removed from the isles. The "Cornish Ensign" (the Cornish cross with the Union Jack in the canton) has also been used.[45][48]

Emergency services

The Isles of Scilly form part of the Devon and Cornwall Police force area. There is a police station in Hugh Town.

The Cornwall Air Ambulance helicopter provides cover to the islands.[49]

The islands have their own independent fire brigade – the Isles of Scilly Fire and Rescue Service – which is staffed entirely by retained firefighters on all the inhabited islands.

The emergency ambulance service is provided by the South Western Ambulance Service with full-time paramedics employed to cover the islands working with emergency care attendants.

Education

Education is available on the islands up to age 16. There is one school, the Five Islands School, which provides primary schooling at sites on St Agnes, St Mary's, St Martin's and Tresco, and secondary schooling at a site on St Mary's. Secondary students from outside St Mary's live at a school boarding house (Mundesley House) during the week. In 2004, 92.9% of pupils (26 out of 28) achieved five or more GCSEs at grade C and above, compared to the English average of 53.7%.[50] Sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds are entitled to a free sixth form place at a state school or sixth form college on the mainland, and are provided with free flights and a grant towards accommodation. Suitably qualified students after age eighteen attend universities and colleges on the mainland.

Economy

Historical context

Since the mid-18th century the Scillonian economy has relied on trade with the mainland and beyond as a means of sustaining its population. Over the years the nature of this trade has varied, due to wider economic and political factors that have seen the rise and fall of industries such as kelp harvesting, pilotage, smuggling, fishing, shipbuilding and, latterly, flower farming. In a 1987 study of the Scillonian economy, Neate found that many farms on the islands were struggling to remain profitable due to increasing costs and strong competition from overseas producers, with resulting diversification into tourism. Recent statistics suggest that agriculture on the islands now represents less than 2% of all employment.[51][52][53]

Tourism

Today, tourism is estimated to account for 85% of the islands' income. The islands have been successful in attracting this investment due to their special environment, favourable summer climate, relaxed culture, efficient co-ordination of tourism providers and good transport links by sea and air to the mainland, uncommon in scale to similar-sized island communities.[54][55] The majority of visitors stay on St Mary's, which has a concentration of holiday accommodation and other amenities. Of the other inhabited islands, Tresco is run as a timeshare resort, and is consequently the most obviously tourist-oriented. Bryher and St Martin's are more unspoilt, although each has a hotel and other accommodation. St Agnes has no hotel and is the least-developed of the inhabited islands.

The islands' economy is highly dependent on tourism, even by the standards of other island communities. "The concentration [on] a small number of sectors is typical of most similarly sized UK island communities. However, it is the degree of concentration, which is distinctive along with the overall importance of tourism within the economy as a whole and the very limited manufacturing base that stands out".[52]

Tourism is also a highly seasonal industry owing to its reliance on outdoor recreation, and the lower number of tourists in winter results in a significant constriction of the islands' commercial activities. However, the tourist season benefits from an extended period of business in October when many birdwatchers ("birders") arrive.

Ornithology

Because of its position, Scilly is the first landing for many migrant birds, including extreme rarities from North America and Siberia. Scilly is situated far into the Atlantic Ocean, so many American vagrant birds will make first European landfall in the archipelago.

Scilly is responsible for many firsts for Britain, and is particularly good at producing vagrant American passerines. If an extremely rare bird turns up, the island will see a significant increase in numbers of birders. This type of birding, chasing after rare birds, is called "twitching".

The islands are home to ornithologist Will Wagstaff.

Employment

The predominance of tourism means that "tourism is by far the main sector throughout each of the individual islands, in terms of employment... [and] this is much greater than other remote and rural areas in the United Kingdom". Tourism accounts for approximately 63% of all employment.[52]

Businesses dependent on tourism, with the exception of a few hotels, tend to be small enterprises typically employing fewer than four people; many of these are family run, suggesting an entrepreneurial culture among the local population.[52] However, much of the work generated by this, with the exception of management, is low skilled and thus poorly paid, especially for those involved in cleaning, catering and retail.[56]

Because of the seasonality of tourism, many jobs on the islands are seasonal and part-time, so work cannot be guaranteed throughout the year. Some islanders take up other temporary jobs 'out of season' to compensate for this. Due to a lack of local casual labour at peak holiday times, many of the larger employers accommodate guest workers, who come to the islands for the summer to have a ‘working holiday’.

Taxation

The islands were not subject to income tax until 1954, and there was no motor vehicle excise duty levied until 1971.[57]

Transport

St Mary's is the only island with a significant road network and the only island with public highways; in 2005 there were 619 registered vehicles on the island. The island also has taxis and a tour bus. Vehicles on the islands are exempt from annual MOT tests.[58][59][60] Roads and streets across Scilly have very few signs or markings, and route numbers (of the three A roads on St Mary's) are not marked at all.

Fixed-wing aircraft services, operated by Isles of Scilly Skybus, operate from Land's End, Newquay and Exeter to St Mary's Airport.[61] A scheduled helicopter service has operated from a new Penzance Heliport to both St Mary's Airport and Tresco Heliport since 2020. The helicopter is the only direct flight to the island of Tresco.[62]

By sea, the Isles of Scilly Steamship Company provides a passenger and cargo service from Penzance to St Mary's, which is currently operated by the Scillonian III passenger ferry, supported until summer 2017 by the Gry Maritha cargo vessel and now by the Mali Rose. The other islands are linked to St. Mary's by a network of inter-island launches.[63] St Mary's Harbour is the principal harbour of the Isles of Scilly, and is located in Hugh Town.

Tenure

The freehold land of the islands is the property of the Duchy of Cornwall (except for Hugh Town on St Mary's, which was sold to the inhabitants in 1949). The duchy also holds 3,921 acres (16 km2) as duchy property, part of the duchy's landholding.[64] All the uninhabited islands, islets and rocks and much of the untenanted land on the inhabited islands is managed by the Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust, which leases these lands from the Duchy for the rent of one daffodil per year.[65] The trust currently has four full-time salaried staff and 12 trustees, who are all residents of the Isles. The full trust board is responsible for policy whilst a management team is responsible for day-to-day administration. Its small income and the small number of staff have led to the trust adopting a policy of recruiting volunteers to help it carry out its extensive work programme. While volunteers of all ages are welcome, most are young people who are studying for qualifications in related fields, such as conservation and land management.

Limited housing availability is a contentious yet critical issue for the Isles of Scilly, especially as it affects the feasibility of residency on the islands. Few properties are privately owned, with many units being let by the Duchy of Cornwall, the council and a few by housing associations. The management of these subsequently affects the possibility of residency on the islands.[66] The Duchy Tenants Association was formed in 1996 by a number of tenants of the Duchy of Cornwall.

Housing demand outstrips supply, a problem compounded by restrictions on further development designed to protect the islands' unique environment and prevent the infrastructural carrying capacity from being exceeded. This has pushed up the prices of the few private properties that become available and, significantly for the majority of the islands' populations, it has also affected the rental sector where rates have likewise drastically increased.[67][68]

High housing costs pose significant problems for the local population, especially as local incomes (in Cornwall) are only 70% of the national average, whilst house prices are almost £5,000 higher than the national average. This in turn affects the retention of 'key workers' and the younger generation, which consequently affects the viability of schools and other essential community services.[54][68]

The limited access to housing provokes strong local politics. It is often assumed that tourism is to blame for this, attracting newcomers to the area who can afford to outbid locals for available housing. Many buildings are used for tourist accommodation which reduces the number available for local residents. Second homes are also thought to account for a significant proportion of the housing stock, leaving many buildings empty for much of the year.[69]

Culture

People

According to the 2001 UK census, 97% of the population of the islands are white British,[3] with nearly 93% of the inhabitants born in the islands, in mainland Cornwall or elsewhere in England.[70] Since EU enlargement in 2004, a number of central Europeans have moved to the island, joining the Australians, New Zealanders and South Africans who traditionally made up most of the islands' overseas workers. By 2005, their numbers were estimated at nearly 100 out of a total population of just over 2,000.[71] The Isles have also been referred to as "the land that crime forgot", reflecting lower crime levels than national averages.[72]

Sport

One continuing legacy of the isles' past is gig racing, wherein fast rowing boats ("gigs") with crews of six (or in one case, seven) race between the main islands. Gig racing has been said to derive from the race to collect salvage from shipwrecks on the rocks around Scilly, but the race was actually to deliver a pilot onto incoming vessels, to guide them through the hazardous reefs and shallows. (The boats are correctly termed "pilot gigs"). The World Pilot Gig Championships are held annually over the May Day bank holiday weekend. The event originally involved crews from the Islands and a few crews from Cornwall, but in the intervening years the number of gigs attending has increased, with crews coming from all over the South-West and further afield.[73]

The Isles of Scilly feature what is reportedly the smallest football league in the world, the Isles of Scilly Football League.[74] The league's two clubs, Woolpack Wanderers and Garrison Gunners, play each other 17 times each season and compete for two cups and for the league title. The league was a launching pad for the Adidas "Dream Big" Campaign[75] in which a number of famous professional footballers (including David Beckham) arrive on the island to coach the local children's side. The two share a ground, Garrison Field, but travel to the mainland for part of the year to play other non-professional clubs.

In December 2006, Sport England published a survey which revealed that residents of the Isles of Scilly were the most active in England in sports and other fitness activities. 32% of the population participate at least three times a week for 30 minutes or more.[76]

There is a golf club with a nine-hole course (each with two tees) situated on the island of St Mary's, near Porthloo and Telegraph. The club was founded in 1904 and is open to visitors.[77]

Media

The islands are served by Halangy Down radio and television transmitter north of Telegraph at 49.932505°N 6.305358°W, on St Mary's, which is a relay of the main transmitter at Redruth (Cornwall) and broadcasts BBC Radio 1, 2, 3, 4 and BBC Radio Cornwall and the range of Freeview television and BBC radio channels known as 'Freeview Light'.[78] Radio Scilly, a community radio station, was launched in September 2007.

There is no local newspaper; Scilly Now & Then is a free community magazine produced eight times a year and is available to mainland subscribers while The Scillonian is published twice yearly and reports matters of local interest. There is an active news forum on the news and information websites scillytoday.com[79] and thisisscilly.com.[80]

Internet access is available across the inhabited islands by means of superfast fibre broadband by BT. The islands connected via fibre are St. Mary's, Tresco and Bryher. St. Martins, St. Agnes and Gugh are connected via a new fibre microwave link from St. Mary's, with fibre cabinets on each island, including Robert.

Mobile phone coverage is available across the archipelago, with 2G, 3G and 4G services available across all islands, although coverage does vary between operators. Vodafone and O2 provide strong 4G coverage across all the islands, whilst EE's is somewhat limited beyond Gugh towards St. Agnes. Three provide 3G coverage to all the islands, and 4G is due shortly.

The Isles of Scilly were featured on the TV programme Seven Natural Wonders as one of the wonders of South West England. Since 2007 the islands have featured in the BBC series An Island Parish, following various real-life stories and featuring in particular the newly appointed Chaplain to the Isles of Scilly. A 12-part series was filmed in 2007 and first broadcast on BBC2 in January 2008.[81] After Reverend David Easton left the islands in 2009, the series continued under the same name but focused elsewhere.[82]

Novels

The heroine of Walter Besant's novel Armorel of Lyonesse came from Samson, and about half the action of the novel takes place in the Isles of Scilly.

The events of Nevil Shute's novel Marazan occur, in part, around these islands.

Five children's books written by Michael Morpurgo, Why the Whales Came, The Sleeping Sword, The Wreck of the Zanzibar, Arthur, High King of Britain and Listen to the Moon are set around the Isles of Scilly.

The Riddle of Samson, a novel by Andrew Garve (a pen name of Paul Winterton) is set mainly around the Isles of Scilly.

In Jacob's Room, by Virginia Woolf, the hero and a friend of his sail around the islands.

The novels that make up The Cortes Trilogy by John Paul Davis take place in the Isles of Scilly.

Stone in the Blood[83] by Colin Jordan and David England is set on the islands both in 1974 and the Iron Age, when most of Scilly was still one joined landmass.

Song

Scilly is mentioned in the traditional British naval song "Spanish Ladies".

Scilly is mentioned in the song "Phenomenal Cat" by The Kinks on their album The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society.

"Isles of Scilly" is a song by the Icelandic artist Catmanic.[84]

Notable people

.jpg.webp)

- Saint Lide was a bishop[85] who lived on the island of St Helen's in the Isles of Scilly.

- John Godolphin (1617 in Scilly – 1678)[86] was an English jurist and writer, an admiralty judge under the Commonwealth.

- Augustus John Smith (1804 in London – 1872 in Plymouth)[87] was Lord Proprietor of the Isles of Scilly for over thirty years. In 1834 he acquired the lease on the Isles of Scilly from the Duchy of Cornwall for £20,000. He was Liberal MP for Truro from 1857 to 1865.

- Sir Frederick Hervey-Bathurst, 3rd Baronet (1807 in Scilly – 1881 in Wiltshire) was a famous English cricketer[88]

- John Edmund Sharrock Moore ARCS (1870 in Rossendale – 1947 in Penzance) was an English biologist, best known for leading two expeditions to Tanganyika. During the 1920s he moved to Tresco.

- David Hunt (1934 in Devonport – 1985 in India) was an English ornithologist and horticulturalist in Tresco and at the Island Hotel where he became the gardener in 1964. He was killed by a tiger in India

- Stella Turk, MBE (1925 Scilly – 2017 in Camborne) was a British zoologist, naturalist, and conservationist. She was known for her activities in marine biology and conservation, particularly as it applies to marine molluscs and mammals.

- Sam Llewellyn (born 1948 in Tresco)[89] is a British author of literature for children and adults.

- Stephen Richard Menheniott (1957–1976) was an 18-year-old English man with learning difficulties who was murdered by his father on the Isles of Scilly in 1976

- Malcolm Bell (born 1969 in Hugh Town) is a former English cricketer. Bell was a right-handed batsman who bowled right-arm medium pace.

See also

References

- Council of the Isles of Scilly - New Appointments 2019

- Council of the Isles of Scilly - Interim Chief Executive

- "Isles of Scilly ethnic groups". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- "Isles of Scilly". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- 'The Fortunate Islands' by R.L. Bowley

- Scillonian Dictionary. Accessed 23 December 2016

- 'The Drowned Landscape' by Charles Thomas.

- Thorgrim. "Nornour". Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- Dudley, Dorothy. "Excavations on Nor'Nour in the Isles of Scilly, 1962–6", in The Archaeological Journal, CXXIV, 1967 (includes the description of over 250 Roman fibulae found at the site)

- "Scilly's Unique Inter Island Walk Sets Off This Morning". Scilly Today. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Weatherhill, Craig (2007) Cornish Placenames and Language. Wilmslow: Sigma Leisure

- "Priscillianus and Priscillianism". Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of Sixth Century. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- Anderson, Joseph (Ed.) (1893) Orkneyinga saga. Translated by Jón A. Hjaltalin & Gilbert Goudie. Edinburgh. James Thin and Mercat Press (1990 reprint). ISBN 0-901824-25-9

- Henderson, Charles (1925). The Cornish Church Guide. Truro: Oscar Blackford. p. 194.

- "Petitioners: Abbot and convent of Tavistock. Addressees: King and council". The National Archives. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Worden, Blair (2012). God's Instruments: Political Conduct in the England of Oliver Cromwell. OUP. pp. 79–81. ISBN 9780199570492

- Banerjee, D.; et al. (1 December 2001). "Scilly Isles, UK: optical dating of a possible tsunami deposit from the 1755 Lisbon earthquake". Quaternary Science Reviews. 20 (5–9): 715–718. Bibcode:2001QSRv...20..715B. doi:10.1016/s0277-3791(00)00042-1. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- History – British History in depth: British Slaves on the Barbary Coast. BBC. Retrieved on 2017-09-29.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Per slate tablet on external wall of Old Town Church, St Mary's, Isles of Scilly, inscribed as follows: "To the memory of Francys, the wife of Joseph Hunkyn of Gatherly in the parish of Lifton in Devon, Governour of the Iland of Silly. She was the daughter of Robert Lovyes of Beardon in the parish of Boydon in Cornwall Esqu. She dyed the 30-day of March 1657 about the 46 (?) yeer of her age." See image and transcript ; For pedigree of "Hunkin of Gatherleigh" see: Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.493

- Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-89577-087-5.

- NCA 158: Isles of Scilly Key Facts & Data at www.naturalengland.org.uk. Accessed on 8 September 2013

- "County flower of Isles of Scilly". Plantlife International – The Wild Plant Conservation Charity. Archived from the original on 18 March 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2006.

- Robinson, H.W. (1925) A New British Animal Discovered in Scilly. Scillonian 4: 123–4

- "Climatological Normals of St. Mary's Heliport 1981–2010". Climatological Information for United Kingdom and Ireland. Met Office]. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- http://www.exeter.ac.uk/news/featurednews/title_528495_en.html

- Met Office Archived 24 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine Fact Sheet – South West England page 17

- "Extreme Temperatures Around the World- world highest lowest recorded temperatures". mherrera.org.

- "St Mary's Heliport Climatic Averages 1981–2010". Met Office. December 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Hiemstra, John F.; et al. (February 2006). "New evidence for a grounded Irish Sea glaciation of the Isles of Scilly, UK". Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (3–4): 299–309. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25..299H. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.01.013. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Scourse 1991, J.D. "Late Pleistocene Stratigraphy and Palaeobotany of the Isles of Scilly". Retrieved 29 March 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Local Government Act 1972 (1972 c.70) section 216(2)

- "Around the Duchy – Isles of Scilly". Duchy of Cornwall. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- "Isles of Scilly Order 1930" (PDF). The National Archives.

- "Isles of Scilly Cornwall through time". visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- "Isles of Scilly RD Cornwall through time". visionofbritain.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 May 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- Examples include the Health and Social Care Act 2003, section 198 and the Environment Act 1995, section 117.

- Leijser, Theo (2015) Scilly Now & Then no. 77 p. 35

- "Council of the Isles of Scilly Corporate Assessment December 2002" (PDF). Audit Commission. Retrieved 21 January 2007.

- Council of the Isles of Scilly Elections

- "Welcome to the Isles of Scilly Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB)". Isles of Scilly Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Welcome to the Isles of Scilly Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority". Isles of Scilly IFCA.

- "Cornwall devolution: First county with new powers". BBC News Online. 16 July 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- "Isles of Scilly (United Kingdom)". fotw.net. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- "How Do You Get A Scillonian Cross". Scilly Archive. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- "Isles of Scilly – The Flag Institute". The Flag Institute. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- "Cornwall (United Kingdom)". fotw.net. Archived from the original on 17 January 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- Busy week for Cornwall Air Ambulance Scilly Today

- School and College Achievement and Attainment Tables 2004 Archived 14 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Department for Education and Skills; retrieved 31 July 2010.

- Gibson, F, My Scillionian Home... its past, its present, its future, St Ives, 1980

- Isles of Scilly Integrated Area Plan 2001–2004, Isles of Scilly Partnership 2001

- Neate, S, The role of tourism in sustaining farm structures and communities on the Isles of Scilly in M Bouquet and M Winter (eds) Who From Their Labours Rest? Conflict and practice in rural tourism Aldershot, 1987

- Isles of Scilly Local Plan: A 2020 Vision, Council of the Isles of Scilly, 2004

- Isles of Scilly 2004, imagine..., Isles of Scilly Tourist Board, 2004

- J.Urry, The Tourist Gaze (2nd edition), London, 2002

- "Travel: Living in a world of their own: On the shortest day of the year, Simon Calder took the high road to Shetland and Frank Barrett took the low road to the Scillies, as Britain's extremities made ready for Christmas". The Independent. London. 24 December 1993.

- Motor Vehicles (tests) Regulations 1981 (SI 1981/1694)

- "A Sustainable Energy Strategy for the Isles of Scilly" (PDF). Council of the Isles of Scilly. November 2007. pp. 13, 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- "Travel Information". ScillyOnLine. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "Skybus Timetables". Skybus. Archived from the original on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- "Home | Penzance Helicopters". penzancehelicopters.co.uk. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- "Isles of Scilly Travel – Travel by sea". Isles of Scilly Travel. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- Sandy Mitchell (May 2006). "Prince Charles not your typical radical". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. pp. 96–115, map ref 104. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Isles of Scilly". Duchy of Cornwall. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

In particular, The Isles of Scilly Wildlife Trust, which manages around 60 per cent of the area of the Isles, including the uninhabited islands, plays an important role in protecting wildlife and their habitats. The Trust pays a rent to the Duchy of one daffodil per year!

- Martin D, 'Heaven and Hell', in Inside Housing, 31 October 2004

- Sub Regional Housing Markets in the South West, South West Housing Board, 2004

- S. Fleming et al., "In from the cold" A report on Cornwall’s Affordable Housing Crisis, Liberal Democrats, Penzance, 2003

- The Cornishman, "Islanders in dispute with Duchy over housing policy", 19 August 2004

- "Isles of Scilly – Country of Birth". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- "East Europeans in the Isles of Scilly". The Guardian. 23 January 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Mawby, R.I. (2002). "The Land that Crime Forgot? Auditing the Isles of Scilly". Crime Prevention and Community Safety. 4 (2): 39–53. doi:10.1057/palgrave.cpcs.8140122. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Rick Persich; Chairman World Pilot Gigs Championships Committee. "World Pilot Gig Championships – Isles of Scilly". Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Smith, Rory (22 December 2016). Welcome to the World's Smallest Soccer League. Both Teams Are Here. The New York Times.

- Beth Hilton (30 October 2007). "Beckham and Gerrard make surprise visit". Scilly News. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Active People Survey – national factsheet appendix". Sport England. Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel) on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- "Isles of Scilly Golf Club". Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "ukfreetv-Full-Freeview vs Freeview Light: map".

- "Scilly Today".

- "This is Scilly – Isles of Scilly News & Information".

- "An Island Parish". BBC. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- "Former Methodist Minister Returns For Visit". The Scillonian. 8 July 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Jordan, Colin; England, David. Stone in the Blood. ASIN 0993586503.

- https://open.spotify.com/album/5OZPMxHZOKkMOpYND4MJxq?si=jV-baMckTnS-3SkYDONiOA

- St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church retrieved 12 October 2017

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900, Volume 22 retrieved 12 October 2017

- Dictionary of National Biography Archived 12 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 12 October 2017

- ESPN CricInfo retrieved 12 October 2017

- Biography of Llewellyn retrieved 12 October 2017

Further reading

- Isles of Scilly Guidebook. Friendly Guides (2015).

- Woodley, George (1822). A View of the Present State of the Scilly Islands: exhibiting their vast importance to the British empire, the improvements of which they are susceptible, and a particular account of the means lately adopted for the amelioration of the condition of the inhabitants, by the establishment and extension of their fisheries. London: Rivington.

External links

- Council of the Isles of Scilly

- Isles of Scilly Tourist Information Centre Website

- Guidebook and detailed maps of Scilly

- Isles of Scilly Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Website

- Map sources for Isles of Scilly

- Cornwall Record Office Online Catalogue for Scilly

- Isles of Scilly at Curlie

- Images of the Isles of Scilly at the Historic England Archive

- Geology of the Isles of Scilly